#1760s Britain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yellow Silk Robe à la Française, 1760-1765, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#yellow#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#1760#1760s#robe à la française#1760s dress#1760s extant garment#1760s britain#V&A

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eva Maria Veigel, Mrs David Garrick, with a mask, attr. to Johann Zoffany, 1752-63

#Johann Zoffany#1750s#1760s#18th century#actress#mdptheatre#theatre#britain#18th c. britain#masquerade#mdp18th c.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

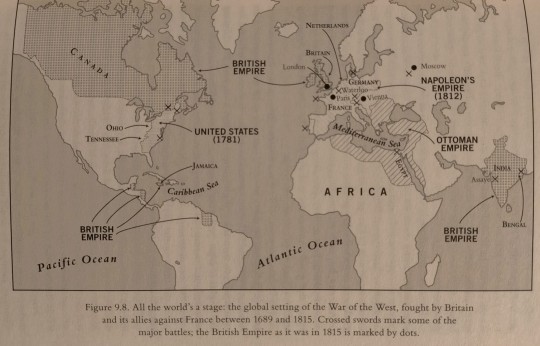

"Our bells are threadbare with ringing of victories," one well-placed Briton bragged in 1759, and in 1763 the exhausted French had no option but to sign away most of their overseas empire (Figure 9.8).

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quotes#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#horace walpole#victory#britain#france#50s#1750s#60s#1760s#18th century#exhausted

0 notes

Text

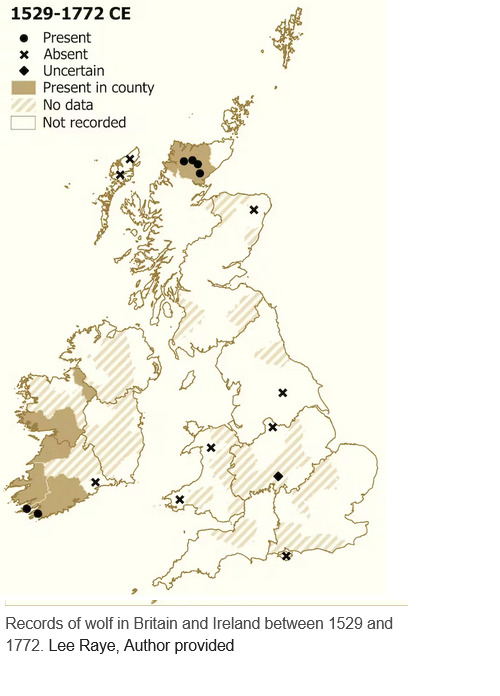

Travel back [...] a few hundred years to before the industrial revolution, and the wildlife of Britain and Ireland looks very different indeed.

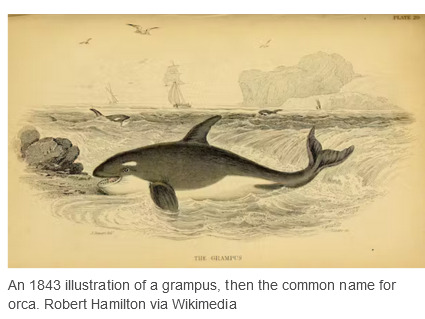

Take orcas: while there are now less than ten left in Britain’s only permanent (and non-breeding) resident population, around 250 years ago the English [...] naturalist John Wallis gave this extraordinary account of a mass stranding of orcas on the north Northumberland coast [...]. If this record is reliable, then more orcas were stranded on this beach south of the Farne Islands on one day in 1734 than are probably ever present in British and Irish waters today. [...]

Other careful naturalists from this period observed orcas around the coasts of Cornwall, Norfolk and Suffolk. I have spent the last five years tracking down more than 10,000 records of wildlife recorded between 1529 and 1772 by naturalists, travellers, historians and antiquarians throughout Britain and Ireland, in order to reevaluate the prevalence and habits of more than 150 species [...].

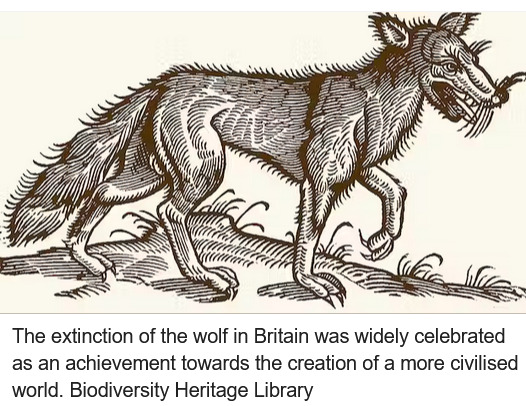

In the early modern period, wolves, beavers and probably some lynxes still survived in regions of Scotland and Ireland. By this point, wolves in particular seem to have become re-imagined as monsters [...].

Elsewhere in Scotland, the now globally extinct great auk could still be found on islands in the Outer Hebrides. Looking a bit like a penguin but most closely related to the razorbill, the great auk’s vulnerability is highlighted by writer Martin Martin while mapping St Kilda in 1697 [...].

[A]nd pine martens and “Scottish” wildcats were also found in England and Wales. Fishers caught burbot and sturgeon in both rivers and at sea, [...] as well as now-scarce fishes such as the angelshark, halibut and common skate. Threatened molluscs like the freshwater pearl mussel and oyster were also far more widespread. [...]

Predators such as wolves that interfered with human happiness were ruthlessly hunted. Authors such as Robert Sibbald, in his natural history of Scotland (1684), are aware and indeed pleased that several species of wolf have gone extinct:

There must be a divine kindness directed towards our homeland, because most of our animals have a use for human life. We also lack those wild and savage ones of other regions. Wolves were common once upon a time, and even bears are spoken of among the Scottish, but time extinguished the genera and they are extirpated from the island.

The wolf was of no use for food and medicine and did no service for humans, so its extinction could be celebrated as an achievement towards the creation of a more civilised world. Around 30 natural history sources written between the 16th and 18th centuries remark on the absence of the wolf from England, Wales and much of Scotland. [...]

In Pococke’s 1760 Tour of Scotland, he describes being told about a wild species of cat – which seems, incredibly, to be a lynx – still living in the old county of Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west of Scotland. Much of Pococke’s description of this cat is tied up with its persecution, apparently including an extra cost that the fox-hunter charges for killing lynxes:

They have also a wild cat three times as big as the common cat. [...] It is said they will attack a man who would attempt to take their young one [...]. The country pays about £20 a year to a person who is obliged to come and destroy the foxes when they send to him. [...]

The capercaillie is another example of a species whose decline was correctly recognised by early modern writers. Today, this large turkey-like bird [...] is found only rarely in the north of Scotland, but 250–500 years ago it was recorded in the west of Ireland as well as a swathe of Scotland north of the central belt. [...] Charles Smith, the prolific Dublin-based author who had theorised about the decline of herring on the coast of County Down, also recorded the capercaillie in County Cork in the south of Ireland, but noted: This bird is not found in England and now rarely in Ireland, since our woods have been destroyed. [...] Despite being protected by law in Scotland from 1621 and in Ireland 90 years later, the capercaillie went extinct in both countries in the 18th century [...].

---

Images, captions, and all text above by: Lee Raye. “Wildlife wonders of Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution – my research reveals all the biodiversity we’ve lost.” The Conversation. 17 July 2023. [Map by Lee Raye. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

For #NationalTeaDay 🫖☕️:

Teapot with Fossil Decoration British, Staffordshire, c. 1760–65 Salt-glazed stoneware with enamel decoration 4 1/4 × 7 1/4 in. (10.8 × 18.4 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 37.22.6a,b

“Though it's got a surprisingly modern look, this teapot was made in the 18th-century in Staffordshire—the heart of Britain's pottery industry. The area’s limestone yielded prehistoric fossils, and potters often turned them into whimsical motifs for teapots.”

#animals in art#european art#British art#decorative arts#ceramics#Staffordshire#pottery#teapot#National Tea Day#tea kettle#monochrome#black and white#fossil#fossils

302 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trail of Tears: Memorial and Protest of the Cherokee Nation by John Ross

The Trail of Tears was the forced relocation of the "Five Civilized Tribes" – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, and Seminole – from their ancestral lands in the Southeastern region of the United States to "Indian Territory" (modern-day Oklahoma) between 1831 and 1850, resulting in the deaths of over 16,000 Native Americans and the removal of over 60,000 from their homelands.

Trail of Tears Memorial at New Echota

Christopher James Culberson (Public Domain)

Scholar John Ehle writes, "the Trail of Tears – or, as the Indians more often said, the Trail Where They Wept – was a trail of sickness" (385). Most Native Americans died of disease, exposure, exhaustion, and starvation on the forced marches from their lands east of the Mississippi River (modern-day Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee) to Indian Territory, a distance of between 1000 miles (1600 km) and over 5000 miles (8000 km), depending on where a given march began and the route taken.

The Trail of Tears was not a singular event but a series of forced relocations following the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The marches began the following year with the Choctaw nation and proceeding through 1847, ending in 1850:

Choctaw: 1831-1836

Seminole: 1832-1842

Muscogee Creek: 1834-1837

Chickasaw: 1837-1847

Cherokee: 1836-1838

Precisely where the term "Trail of Tears" originated is debated, but it is usually attributed to a Choctaw chief who described the journey as "a trail of tears and death." Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

The originator of this simple phrase is not known for sure, but it is believed to have been used by a Choctaw chief, Nitikechi, to describe the effects of the Indian Removal Act. The Cherokee had a similar term: "The Place Where They Cried."

(500)

Cherokee Chief John Ross (l. 1790-1866) famously opposed the removal in his Memorial and Protest of the Cherokee Nation sent to Congress in June 1836, arguing that the US government had no legal grounds for relocating his people. Although his piece focuses on the Cherokee nation, the points he makes apply equally to the others who were forcibly removed from their lands.

Although the Trail of Tears is the best-known act of forced relocation of Native Americans, it is far from the only one as citizens of many other nations of Native peoples of North America experienced the same throughout the 19th century and up to as recently as the mid-1960s to the 1970s. This event, and others like it, notably the Long Walk of the Navajo (1863-1866) are, generally, understood today as acts of genocide perpetrated by the US government.

Background to the Marches

Although the Indian Removal Act of 1830 was the immediate cause for the death marches known as the Trail of Tears, the policies informing that act date back to the 1630s, notably the Pequot War (1636-1638), which reduced the Pequot population of the region of modern-day Massachusetts from 3000 to 200 (many then sold into slavery) to open up their lands for English colonization. Among the "facts submitted to a candid world" presented by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence of 1776 was that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820)

Has excited domestic insurrections amongst us and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.

As president, in 1803, Jefferson advocated the forced removal of Native Americans west of the Mississippi River and, by 1819, citizens of Native American nations were offered 640 acres of land in Indian Territory for giving up their lands east of the Mississippi. The US government in 1819 had no authority to grant these acres to anyone, however, as they were in so-called "Indian Territory" and, as John Ross points out below, the US government had no legal right to forcibly remove Native Americans from their homelands for relocation in the west.

Westward Exploration and Settlement of the United States c.1850

Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-ND)

The solution to the "Indian Problem", included in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, was to buy the land from Native Americans, and then, having nowhere to live, they might be amenable to moving west on their own, which the US government promised to help them do. Although the cause of the Trail of Tears is often attributed to the Georgia Gold Rush of 1829, which brought miners into conflict with Native Americans living there, President Andrew Jackson already had Native American relocation as a priority when he took office that year.

Continue reading...

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress. Scotland, Glasgow (place of manufacture), circa 1863. Wool, cotton.

Glasgow Museum Collections

Woman’s dress in light purple wool embroidered with in purple and white thread in tambour-work in an abstract pattern. High round neckline trimmed with lace, bodice loosely pleated from shoulders to wide v-shape at straight waistline with two narrow vertical pieces of gauze with tambour-work centre front with fastening behind of nine metal hooks and thread eyes attached to lining. Full-length sleeves with short pointed frill at shoulder edged with tambour-work, applied narrow piece of gauze around lower arm to suggest folded back cuff, hem edged with white lace. Skirt, full-length, pleated into waistband with tambour-work border around lower half, opening at front fastened by two metal hooks and thread eyes with small watch pocket in waistband. Bodice and sleeves lined with glazed cotton, skirt lined with cotton.

This beautiful dress is made from light purple wool. The silhouette follows the fashions of the early 1860s with a softly draped bodice and wide, full-length skirt that would have been held out by a steel-framed cage-crinoline.

The dress is decorated with an abstract pattern in purple and white thread tambour-work. The stitch resembles chain-stitch but is worked with the cloth stretch over a hoop, known as tambour, using a small hook rather than a needle. The technique originated in India and reached Britain the 1760s. By the early 19th century the west of Scotland was a leading centre for manufacturing tamboured muslins, with up to 20,000 women and girls in total working in the British industry.

497 notes

·

View notes

Note

What did masculinity mean to sailors in the Royal Navy in Victorian times?

uff that's a question that i can't just answer. Because there are whole academic theses that just deal with it, because there are many aspects involved. Masculinity was always an issue, but it became particularly important under Queen Victoria, because now a woman was in power and there were hardly any wars. Hence the focus on discovery and emphasising the growing empire.

At home, the man was still a gentleman and showed this in his appearance, but the soldier, sailor or officer is different, his appearance is designed for power and masculinity and is shown in the uniforms. Earlier in the 18th -early 19th century the man was a gentleman especially the officer, the Sailor a workhorse without uniform. Later we move away from wide coats and towards narrow waists, broad shoulders emphasised by wide epaulettes and the sailor himself gets a uniform, which forms a completely different image. Together with the way the world itself is changing, this appearance is also intentional. Politics is changing, the tone is getting rougher, the man is in demand again and this is also reflected in the armies, not necessarily in society itself, because there the man is an elegant gentleman. outwardly, however, you have to show strength and must not allow yourself any weakness, because even if you are ruled by a queen, it is her men who show and demonstrate their power to the outside world. This, let's call it men's behaviour, this proud, strong appearance continued until the Second World War, only from then on did it slowly diminish.

This is just a small outline of what research is concerned with and it is a really deep subject. If you would like to read more about it, have a look at Manliness in Britain, 1760-1900 and here.

https://scholarspace.library.gwu.edu/downloads/000000506?disposition=inline&locale=en

But I hope I have been able to help you at least a little further.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

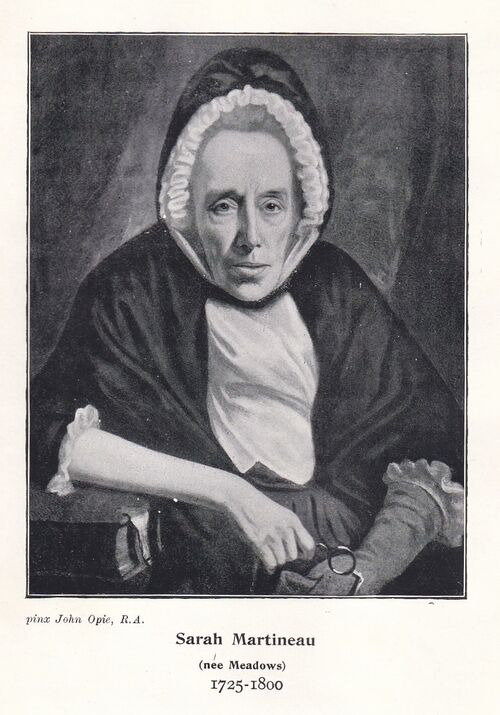

The Martineau Family | French Huguenots Norwich Maître Chirurgien (Master Surgeon), David Martineau (1726-1768) and his wife Sarah Meadows (1725-1800). David Martineau was the grandson of Gaston Martineau (c. 1654-1726), a surgeon in Dieppe, who moved to Norwich after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685; the edict had allowed French Protestants freedom of religion and the Huguenots left France for safety. The arrival of this large amount of new immigrants into Britain in the 1680s meant that a new word came into the English language to describe them: ‘rés’ or refugees. They are therefore considered the ‘first refugees’ to arrive to the British Isles.

The Princess of Wales (b. 1982) is a descendant of the couple via their son Thomas Martineau, a textile manufacturer (1764-1826) and his wife Elizabeth Rankin (1772-1848) the couples second daughter was famed sociologist and abolitionist Harriet Martineau (1802-1876). Film Director Guy Ritchie (b. 1962) is a descendent of David and Sarah Martineau via their son Peter Finch Martineau, a businessman and philanthropist (1755-1847) and his wife Catherine Marsh (1760-1853). The Princess and Guy Ritchie are 6th cousins 1x removed.

#ktd#british royal family#brf#The Martineau family#harriet martineau#guy ritchie#princess Catherine#princess of wales#Art#black and white#history#Huguenots

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

In “Choices” what is the agreement between England and Prussia that Mattie mentions??

So the famous one is the 1914 Christmas truce which was British and German soldiers. And all across the front similar smaller ones would happen. It was by and large British soldiers who would adopt live and let live mentalities. The Australians had similar situations in Gallipoli and also joined in on smaller rarer occasions with general British trends of being less murderous against German positions. The French have had a scattering. Usually between British and German soldiers. It's possible I've missed one but no Canadian unit is widely recognized as to have participated in any single incident and were often pushed into sections of the front line to lead aggressive raids into positions where truces had occurred to make full use of any unsuspecting German front line soldiers and kill them.

For all Britain likes to distinguish itself from Europe especially in the imperial 'splendid isolation' these are still people Arthur, Rhys and Alasdair have known for literally hundreds and thousands of years. They understand and specifically Arthur with all his German monarchs understands that things change and violence inflicted now becomes violence that could be turned and reinflicted later. He and Gilbert have been friends and lovers and supports and rivals across centuries. They aren't out to destroy each other to nearly the same degree Gilbert and Francis are.

All of it disgusts Matt. From his perspective, Arthur dragged him to France to kill Germans. Anything less than the hardest push to do that renders the entire exercise pointless. He's the First Dominion and eldest present son of the British Empire. His job is to keep his family safe. There's this very specific tenderness in Matt Arthur has been very uncomfortable with because it's just kind of awkward and vulnerable to see and receive and thus has spent centuries preferring his children disassociate rather than commit the ultimate anglo sin of making a fuss. But here he is often avoiding the killing blows because again, change is inevitable and he often couches it in affectionate language for Gilbert. Less so Ludwig but pre-WW2 Arthur has had a certain hesitancy to open fire on him. Matt lacks both some of the perspectives needed to restrain his violence but also has just a deep seated and terrifying well of rage he's been sitting on since at least 1760. It gets unleashed on Ludwig and Gilbert and anything or anyone who got in his way. It's hard to tell with Matt sometimes, if what he's done was done because he had an outlet his father sanctioned or out of loyalty. And at some point fairly early in the war, Arthur lost the ability to put Matt on a leash. It's not the first time Matt has not only disagreed with but defied an Arthur making pragmatic or less violent choices (which is a hell of a sentence to be writing about the British Empire but it has been occasionally true.) His actions undertaken during the Great War is by far the largest body count to result from it.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Priam Pleading with Achilles for the Body of Hector

Artist: Gavin Hamilton (Scottish, 1723–1798)

Date: 1775

Medium: Oil paint on canvas

Collection: Tate Britain, London, United Kingdom

Description

Hamilton spent much of his life in Rome. His paintings from ancient history, painted there in the 1760s and widely known through prints, were highly influential. The most famous were six subjects from Homer's 'Iliad' of which this, commissioned by Lord Mountjoy and engraved in 1775, was the fifth. Priam, King of Troy, prostrates himself before Achilles to plead for the body of Hector, which Achilles has desecrated in furious revenge for the death of his friend Patroclus; Achilles begins to yield to compassion. The frieze-like composition is derived from Roman sarcophagus sculpture, and the heroic figures, with their emphatic gestures and expressions, from Poussin, whose paintings Hamilton admired.

#literary scene#homer's iliad#oil on canvas#narrative art#interior#male figures#female figures#artwork#painting#fine art#oil painting#drapery#priam king of troy#achilles#scottish culture#scottish art#gavin hamilton#scottish painter#literature#european art#18th century painting#tate britain

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hand-painted Chinese silk robe and petticoat, probably English, c. 1760-1765. Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery.

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

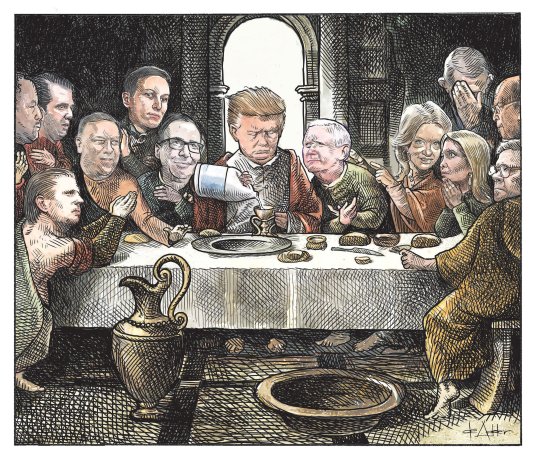

The Chronicle Herald :: Michael de Adder :: @deAdder

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

July 28, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Jul 29, 2024

Just a week ago, it seems, a new America began. I’ve struggled ever since to figure out what the apparent sudden revolution in our politics means.

I keep coming back to the Ernest Hemingway quote about how bankruptcy happens. He said it happens in two stages, first gradually and then suddenly.

That’s how scholars say fascism happens, too—first slowly and then all at once—and that’s what has been keeping us up at night.

But the more I think about it, the more I think maybe democracy happens the same way, too: slowly, and then all at once.

At this country’s most important revolutionary moments, it has seemed as if the country turned on a dime.

In 1763, just after the end of the French and Indian War, American colonists loved that they were part of the British empire. And yet, by 1776, just a little more than a decade later, they had declared independence from that empire and set down the principles that everyone has a right to be treated equally before the law and to have a say in their government.

The change was just as quick in the 1850s. In 1853 it sure looked as if the elite southern enslavers had taken over the country. They controlled the Senate, the White House, and the Supreme Court. They explicitly rejected the Declaration of Independence and declared that they had the right to rule over the country’s majority. They planned to take over the United States and then to take over the world, creating a global economy based on human enslavement.

And yet, just seven years later, voters put Abraham Lincoln in the White House with a promise to stand against the Slave Power and to protect a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” He ushered in “a new birth of freedom” in what historians call the second American revolution.

The same pattern was true in the 1920s, when it seemed as if business interests and government were so deeply entwined that it was only a question of time until the United States went down the same dark path to fascism that so many other nations did in that era. In 1927, after the execution of immigrant anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, poet John Dos Passos wrote: “they have clubbed us off the streets they are stronger they are rich they hire and fire the politicians the newspaper editors the old judges the small men with reputations….”

And yet, just five years later, voters elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who promised Americans a New Deal and ushered in a country that regulated business, provided a basic social safety net, promoted infrastructure, and protected civil rights.

Every time we expand democracy, it seems we get complacent, thinking it’s a done deal. We forget that democracy is a process and that it’s never finished.

And when we get complacent, people who want power use our system to take over the government. They get control of the Senate, the White House, and the Supreme Court, and they begin to undermine the principle that we should be treated equally before the law and to chip away at the idea that we have a right to a say in our government. And it starts to seem like we have lost our democracy.

But all the while, there are people who keep the faith. Lawmakers, of course, but also teachers and journalists and the musicians who push back against the fear by reminding us of love and family and community. And in those communities, people begin to organize—the marginalized people who are the first to feel the bite of reaction, and grassroots groups. They keep the embers of democracy alive.

And then something fans them into flame.

In the 1760s it was the Stamp Act, which said that men in Great Britain had the right to rule over men in the American colonies. In the 1850s it was the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which gave the elite enslavers the power to rule the United States. And in 1929 it was the Great Crash, which proved that the businessmen had no idea what they were doing and had no plan for getting the country out of the Great Depression.

The last several decades have felt like we were fighting a holding action, trying to protect democracy first from an oligarchy and then from a dictator. Many Americans saw their rights being stripped away…even as they were quietly becoming stronger.

That strength showed in the Women’s March of January 2017, and it continued to grow—quietly under Donald Trump and more openly under the protections of the Biden administration. People began to organize in school boards and state legislatures and Congress. They also began to organize over TikTok and Instagram and Facebook and newsletters and Zoom calls.

And then something set them ablaze. The 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision stripped away from the American people a constitutional right they had enjoyed for almost fifty years, and made it clear that a small minority intended to destroy democracy and replace it with a dictatorship based in Christian nationalism.

When President Joe Biden announced just a week ago that he would not accept the Democratic nomination for president, he did not pass the torch to Vice President Kamala Harris.

He passed it to us.

It is up to us to decide whether we want a country based on fear or on facts, on reaction or on reality, on hatred or on hope.

It is up to us whether it will be fascism or democracy that, in the end, moves swiftly, and up to us whether we will choose to follow in the footsteps of those Americans who came before us in our noblest moments, and launch a brand new era in American history.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#last supper#about art#Michael de Adder#political cartoon#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#American political history#politics#anti-authoritarianism#anti-democratic#election 2024

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a direct connection between the expansion of [...] new [coffee] consumer culture in Europe [...] and the expansion of plantation slavery in the Caribbean. [...] [S]lave-based coffee was more important to the Dutch [Netherlands] economy than previously [acknowledged] [...]. [T]he phenomenal growth of [plantation slavery in] Saint Domingue [the French colony of Haiti] was partly made possible by the export market along the Rhine that was opened up by the Dutch Republic. [...] [E]arly in the eighteenth century, the Dutch and French began production in their respective West Indian colonies [...]. [C]offee was still a very exclusive product in Europe. [...] From the late 1720s, [...] in the Netherlands [...] coffee was especially widespread [...]. From the late 1750s the volume of Atlantic coffee production [...] increased significantly. It was at that time that the habit of drinking coffee spread further inland [...] [especially] in Rhineland Germany [...] [and] inland Germany [due to Dutch shipments via the river].

Although its consumption may not have been as widespread as the tea-sugar complex in Britain, there certainly was a similar ‘coffee-sugar complex’ in continental Europe [...] spread during the eighteenth century [...]. The total amount of coffee imported to Europe (excluding the Italian [...] trade) was less than 4 million pounds per year during 1723–7 and rose to almost 100 million pounds per year around 1788 [...]. In 1790 [...] almost half of the value of [Dutch] exports over the Rhine [to Germany] was coffee. [...]

---

The rising prices in the 1760s encouraged more investment in coffee in Dutch Guiana and the start of new plantations in Saint Domingue [Haiti]. Production in Saint Domingue skyrocketed and surpassed all the others, so that this colony provided 60% of all the coffee in the world by 1789. [Necessitating more slave labor. The Haitian revolution would manifest about a decade later.] [...]

In French historiography, the ‘Dutch problems’ are considered to be the slave revolts (the Boni-maroon wars) [at Dutch plantations]. [...] France made use of the Dutch ‘troubles’ to expand its market share and coffee production in Saint Domingue [Haiti], which accelerated at an exponential rate. [...]

---

[T]he Dutch Guianas [were] producing over a third of the coffee consumed in Europe [...] [by] 1767. [...] The Dutch flooded the Rhine region with coffee and sugar, creating a lasting demand for both commodities, as the two are typically consumed together. [...] [T]he history of the slave-based coffee production in Surinam and Saint Domingue [Haiti] was pivotal in starting the mass consumption of coffee in Europe. [...] Slave-based coffee production was also crucial [...] in Brazil during the 'second slavery', where slavery existed on an enormous scale and was reshaped in the world's biggest coffee producing country [later] during the nineteenth century. [...] The Dutch merchant-bankers organised coffee investment, enslavement, and planting and selling; [all] while not leaving the town of Amsterdam [...].

[This market] expansion ends in crisis [...] - a crisis caused by uprisings and revolutions, most notably, the Haitian one. Yet Germans still liked coffee. And the Dutch colonial merchant-banker[s] [...] learned something about [...] production, and perhaps also something about the role of the state in labour control: as soon as they could, they sent Johannes van der Bosch [Dutch governor-general of the East Indies] to Surinam and Java in order to solve the labour issues and expand the colonial production of coffee [by imposing in Java the notoriously brutal cultuurstelsel "enforced planting" regime, followed later by the "Coolie Ordinance" laws allowing plantation owners to discipline "disobedient" workers, with millions of workers on Java plantations, lasting into the twentieth century].

---

Text above by: Tamira Combrink. "Slave-based coffee in the eighteenth-century and the role of the Dutch in global commodity chains". Slavery & Abolition Volume 42, Issue 1, pages 15-42. Published online 28 February 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. All of that italicized text within brackets was added by me for clarity and context; apologies to Combrink. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism.]

#abolition#ecology#caribbean#tidalectics#intimacies of four continents#ecologies#archipelagic thinking#indigenous#multispecies#european coffee#slavery hinterlands

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of the Drummond Family, Peter Auriol Drummond (1754-1799), Mary Bridget Milnes Drummond (1755-1835), and George William Drummond (1761-1807)

Artist: Benjamin West (American-active Britain, 1738-1820)

Date: c. 1776

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Description

Born in Pennsylvania, Benjamin West moved to Europe in 1760, studying primarily in Italy before settling in London in 1763. One of his first important patrons was Robert Hay Drummond, the Archbishop of York. Drummond attempted to raise an annual salary for West so that the artist could devote his time to producing grand historical paintings, rather than be confined to the lucrative work of portraiture. When this effort failed, Drummond introduced West to King George III, who recognized the artist's abilities and eventually appointed him Historical Painter to the King. West achieved tremendous fame and financial success in London and helped establish the prestigious Royal Academy in 1768.

This family portrait depicts four members of the Drummond family. At far right is Peter Auriol Hay Drummond, the third son of the Archbishop and an officer in the 16th Light Dragoons. Next to him is his wife, the former Mary Bridget Milnes. On the left is the Archbishop's sixth son, George Hay Drummond, a clergyman in the Anglican church, who holds a painting of the fourth "sitter,", the archbishop. Some scholars have suggested this is intended as a memorial, and must date to after the archbishop's death on December 10, 1776. Others have suggested that the painting might precede his death, since none of the sitters give any indication of mourning. Perhaps the archbishop's duties in York prevented him from sitting for the portrait in London, so West included him with the clever conceit of representing a portrait painting in the work.

#portrait#drummond family#oil on canvas#peter auriol hay drummond#mary bridget milnes#george hay drummond#woman#men#interior scene#american-british culture#american-british painter#fine art#oil painting#artwork#three quarter length#chairs#curtain#costume#cloudy horizon#benjamin west#european art#18th century painting#minneapolis institute of art

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

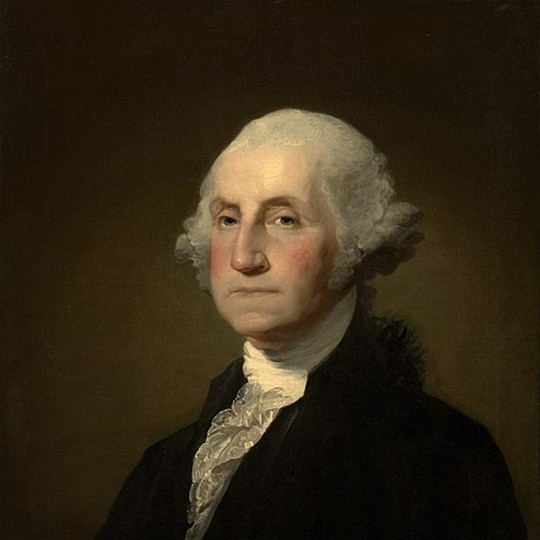

Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States were the leaders of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789), who led the push for American independence from Great Britain, founded the United States, and oversaw the implementation of the US Constitution in the tumultuous years following the war.

While the term 'Founding Father' can apply to many influential individuals from the American Revolutionary period, this collection looks at 15 of the most significant. It includes the men who spearheaded the initial struggle against Parliament in the 1760s, the writers of the Declaration of Independence, influential figures in the Second Continental Congress, which oversaw the course of the American Revolutionary War, as well as the first five presidents of the United States.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes