#1730s extant garment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Silk Embroidered Robe à la Française, 1730-1740, European.

Met Museum.

#silk#1730s#1730s dress#1730s extant garment#European#extant garments#dress#robe à la française#embroidery#womenswear#silver

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silk damask robe a'langlaise. Spitalfields silk c.1735, dress c.1765.

via fashionmuseum.fitnyc.edu

#fashion history#history of fashion#historical fashion#history of dress#18th century#18th century fashion#robe a l'anglaise#spitalfields silk#1700s#1700s fashion#extant garments#pink#1730s#1760s#e

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm trying to draw something for a friend. Both of our characters live in the late 1720s. They both have regular outfits, but I want to draw them wearing something fancy. My friend has described his character as having a very bad sense of fashion. I can't really picture what a bad outfit back then would look like. Do you?

Hello! Well I haven't got all that much of a feel for what might have been considered a bad outfit back then, but there is one image that immediately comes to mind of someone who's very definitely badly dressed, and it's this guy. From the 4th panel of Hogarth's Marriage A la Mode (1743-45).

His individual garments look fine to me, but they're horribly mismatched! (And a bit old fashioned for the mid 40's.) You'll note that the coat cuffs are made of a large brocade that contrasts with the main body of the coat, which was very popular in the first half of the century, but that style was meant to be worn with a matching waistcoat in the same brocade. Instead he's got a completely plain waistcoat that doesn't match at all.

And the breeches should match the main coat fabric, but his don't! The black and brown and beige clash awfully. He's also got a lot more rings and a much bigger & sparklier earring than I've seen on any other guy from the era, which I speculate might have been tack and/or un-masculine, but I have no sources so don't quote me on that. I just know that when 18th century guys are wearing rings in a portrait it's usually just one, and I've only ever seen simple little hoop earrings in a very few portraits. But again, emphasis on the "speculate" part of that sentence.

(And I've just noticed that the guy next to him has curling papers in his hair, which I think is probably also meant to make him look silly and not properly dressed. No idea what the opinion would have been about the folding fan dangling from the wrist of the next guy over, but it is intriguing. The very large beauty spot on his lip is probably meant to look bad though.)

That painting is a bit later than what you're asking about, but the style of matching cuffs & waistcoat was popular in the 20's too, so here are some examples of what it's supposed to look like. A lot of them are very elaborate brocades paired with a solid dark coloured velvet, but sometimes it's a contrasting plain fabric with a ton of metal embroidery.

(1725)

(1723)

And an extant c. 1730's example from the NMS collection.

You might also look at 1710's images, because being a decade behind the current fashions would certainly make you badly dressed for the era.

(c. 1715-20)

So, I guess just put them in clashing parts of 2 or 3 different matched suits? (I am assuming you're asking about suits, since this ask was sent to me and I do not know very many things about dresses. Mostly only what I absorb from other costumers who post about it, and barely anyone does early 18th century.)

Please note that this does not apply to the 1780's-90's, fashion plates from those decades are incredibly full of clashing and mismatched suits. (Though it would probably still be bad to wear those ones on a very formal occasion.)

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dating a Jacket, Part 1

The Eighteenth-Century Assumption

Part 2 here

Sometimes you come across a piece of clothing and the date just seems a little too ambiguous. That was the case with this jacket, number 1981.314.2, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is said to be from the 2nd quarter of the 18th century. The good people at the Costume Institute within the Met were kind enough to take detailed photos of the jacket for me, including details of construction. These images were invaluable in allowing me to create my own version, but have also given me some questions about their chosen date. I am not allowed to share the images they took for me without express permission, so if necessary I will include photos from my own jacket.

First, let us remind ourselves of what the jacket looks like:

Left: jacket, Italian, 1981.314.2. Dated 2nd quarter 18th c. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: my own recreation of the same jacket.

The Met gives the original jacket a moderately wide date range of 2nd quarter of the 18th century, so between 1725 and 1750. And I can see what influenced them to make that decision. At first glance, the overall shape has strong similarities with the examples below of wide-necked riding jackets.

Left: Casaquin, textile 1710-1720, garment 1720-1730. Right: Casaquin, c. 1730-1740. Both from Palais Galliera

Left: Agnieszka Emercjanna Pociej ascribed to Ádám Mányoki, before 1722. Right: Lucy Pelham-Holles by Godfrey Kneller, 1722.

Left: Sophie Marie von Voss by Antoine Pesne, 1746-1751. Right: Maria-Antonia von Fürstenberg by Franz Josef Weiss, 1758.

Please note, however, that regional fashion changes do exist and none of the examples are Italian. I could not find any images of similar jackets from Italy. If anyone does have images of riding habits/jackets from Italy in the first half of the 18th century, I'd love to see them! However, these images do show at least a moderate geographic distribution of this trend: France, Germany (Prussia and Swabia), England, and Poland. All of the examples feature a wider neckline than the close-to-the-neck style found in men's coats and in some other women's riding jackets, and also feature metallic trim embellishing the front and cuffs. So far, so good, right? Well--let's dig deeper.

First, what do I mean by "riding jacket?" I am using the phrase to denote these and other women’s jackets from the 17th and 18th century that are inspired by menswear and originally used for the purpose of riding and hunting. Some of you may be more familiar with the term "riding habit" in which the jacket is worn with a matching petticoat and maybe a waistcoat to create a complete outfit.

Many of these jackets have trends directly borrowed from menswear like pockets and button-fronts, and fasten at the center front without a stomacher. However, as riding jackets and riding habits became an acceptable part of fashionable dress, some of these characteristics may have been adapted, or vanished almost entirely, as is the case with the two French casaquins seen above. These jackets represent the way that practical garments adapted to fashionable tastes. You can see Mme Gaspard de Peleran wearing a very similar jacket in this sketch by Liotard–its equestrian nature is denoted by the long riding whip she holds in her hand.

Madame Gaspard de Péleran by Jean-Etienne Liotard, est 1738-1742 (my estimate is based on Liotard's residence in Turkey from 1738 to 1742, where the subject's husband was French Consul in Smyrna)

So where do my doubts about the Met's jacket come from? Well, it's mainly the construction. When we look at extant riding jackets, however, the vast majority of the (admittedly few) originals have front waist seams, something absent from my own. The brocade casaquin above? waist seam. The pink casaquin? can't say, hidden by lace, could be either. This 1730-1750 riding jacket from the Snowshill Wade Costume collection was even patterned in Janet Arnold's Patterns of Fashion Volume 1, pp 24-25, so you can really see the waist seam:

Whether plain or ornate, you'll probably find a waist seam!

Left: Riding Jacket, 1740s, John Bright Collection. Right: Riding Coat, 1750-1759, V&A Museum.

I found exactly one riding jacket which clearly does not have a front waist seam, and it's from very early in the period:

Jacket, 1710-1725, Palais Galliera.

If we look at paintings, we do find a few more examples that seemingly don't have a waist seam. Some of these might be artistic license or simply the artist not wanting to paint every single seam, but I'm inclined to believe at least some of them, like this painting by Nicholas Lancret:

Picnic After the Hunt (detail) by Nicolas Lancret, 1735-1740, National Gallery of Art.

Why do I trust it? The waist wrinkles. Ask me how I know...

Okay, so, a waist seam of lack thereof isn't proof one or the other about dating. But there are other oddities of construction as well. For instance, looking at this picture of my own jacket, do you see the pocket? These pockets have no flap and are cut straight across, whereas every other example I've shown so far has a pocket flap. This is much more in keeping with men's coats from the same period:

Left: Coat, British, 1720s, Met Costume Institute. Right: Coat, German, 1720s-1730s, LACMA.

Also, where are the rest of the buttons? The jacket held by the Met has 100 buttons total--33 along the front, 8 along each pocket, and 17 along the side and back vents. These men's coats, the most button-heavy of all the examples shown here, have buttons along the fronts, below the pocket flaps, and along the top cuffs, but none running along the vents:

In addition, the Met jacket has large contrasting cuffs, which does not seem to be as much an element of jackets from the 2nd quarter of the 18th century, unless it matched a waistcoat.

Top: Le Repas au retour de la chasse (detail) by Nicolas Lancret, c. 1725. Bottom Left: Anna Katarzyna Orzelska by Louis de Silvestre, c.1730. (red waistcoat matching cuffs is just visible at front opening below lace). Bottom Right: Coat, c. 1735, National Museums Scotland.

None of these cuffs have a heavy trim around the edge though, like the pleated pink ribbon and silver braid on the Met's jacket. It is possible that the cuffs and trim are a later addition, but just comparing the braid on the cuffs to the braid on the rest of the jacket, they appear to be the same 4-strand silver metallic braid.

While this does not rule out the possibility that they were an addition made at a different time, it does make it, in my opinion, most likely that the cuffs are contemporary to the rest of the jacket. In addition, most cuffs of 1725-1750 jackets and coats are cut separately to the sleeve and then attached, whereas the cuffs of my jacket are cut in one with the sleeve and folded back.

So where does that leave us? Well, the Met appears to be correct in noticing that wide-necked riding jackets are largely a phenomenon of the early-to-mid 18th century. The large turned-back cuffs and lack of a waist seam would probably push this earlier in their proposed date range, closer to the 1720s than the 1750s. In my next post, however, I will introduce another possibility--what if the jacket is earlier? Maybe even much earlier?

Part 2

Additional Resources:

Images of more riding jackets found at the 18th Century Notebook from Larsdatter

@vincentbriggs has detailed posts on 1730s coat construction here and here, and in general is a font of knowledge for 18th-century tailoring.

jeannedepompadour.blogspot.com has a good collection of images of early 18th-century riding jackets.

Janet Arnold, Patterns of Fashion vol 1. Originally Published 1972, reissued 2021 by School of Historical Dress.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Collar and mitts ca. 1725-50

From Cora Ginsburg

435 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the what would you wear ask: the first one you haven't done of 'to a fae gathering', 'to the met gala 2o19' or 'within the theme of ‘bohemian’, please? (Thought I'd hadge my bets in case u had got the first already!!)

I got the fae gathering one already, but not the Met Gala one!I think I’d wear this to the Met Gala 2019:

(Coat, c. 1730′s. Palais Galliera.)

I have no idea why this utterly bizarre coat exists, and can only assume it was made for theatre or a fancy dress party. The cut is pretty typical of the decade, but the fabric choice? VERY weird! I think it’d fit the “camp” theme tolerably well.

#ask#ask meme#gothicmarquise#1730's#extant garments#coats#fashion#striped mens coats weren't a thing until like 50 years later and even then they were much narrower stripes

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Collective 18th Century Library

This is a selection of books about the 18th century fashion, history, beauty, and life. Most of them in my personal library or have consulted but have not bought (yet). This post is going to be edited with more books added and reblogged for all to see, that’s why I called this post “our collective 18th century library”, from me to you all and then for you all to all of us.

Please add other books you have in your collections or you’ve read! And if you could keep the format (cover photo, book info, a little comment, the themes we can find in the book, and the link of where to find them), it will be consistently useful for everyone!

Let’s start:

ART

Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico, by Ilona Katzew, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN-10: 0300109717

Casta painting is a whole genre created in Mexico for depicting the population of the New Spain, and it’s whole purpose was to show the Spanish King what an organised viceroyalty it was, and how everyone has their proper place, even if that was not entirely true.

Themes: fashion (for visual reference), castas, race, Mexico, New Spain, Viceroyalty, the Americas, Mexico City, art, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Barnes and Noble / Waterstones

Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici, edited by Ilona Katzew, Prestel Publishing, 2017, ISBN: 978-3-7913-5677-8

The book from the exhibition about art made in Mexico City during the 18th century.

Themes: art, portraits, casta painting, Mexico, Mexico City, Viceroyalty, New Spain, the Americas, castas, religion, catholicism, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Amazon (Spanish version) / Target / Waterstones

HISTORY

A History of Private Life, Volume III: Passions of the Renaissance, Edited by Roger Chartier, Series edited by Phillippe Ariès, Harvard University Press, 1993, ISBN 9780674400023

The life or ordinary people from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, centered in Europe and especially France, you’ll read about the everyday lives of women and children, common men, education, marriage and well, the private life. This whole series (of 5 volumes) is worth each penny.

Themes: everyday life, history, women, Europe, France, children, education, Renaissance, Enlightenment, 16th century, 17th century, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Harvard University Press

A History of Private Life, Volume IV: From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War, Edited by Michelle Perrot, Series edited by Phillippe Ariès, Harvard University Press, 1993, ISBN 9780674400030

The first part is 18th century and deals with life pre, during and after French Revolution.

Themes: everyday life, history, women, Europe, France, children, education, Enlightenment, French Revolution, Victorian, Belle Epoque, WWI, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century.

Available at: Amazon / Harvard University Press

Black London: Life Before Emancipation, by Gretchen Gerzina, Rutgers University Press, 1995, ISBN-10: 0813522722

A glimpse into the lives of the thousands of Africans living in eighteenth century London.

Themes: everyday life, history, race, black, African, England, London, slavery, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / You can also download it for FREE (ha! who needs Amazon now?)

Historia De La Vida Cotidiana En México 3: El siglo XVIII: entre la tradición y el cambio, by Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2012. ISBN-10: 9681677188

Common life in Mexico during the 18th century, from fashion, food and the markets, to the everyday life of mining cities, children and monks. This is book is a key reference for starting to read about the life of common people in the New Spain. Part of a series from the prehispanic times to the 20th century.

Themes: fashion, food, everyday life, New Spain, Mexico, Viceroyalty, The Americas, castas, mining, religion, catholicism, education, childhood, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Cambridge University Press / Fondo de Cultura Económica

FASHION

Auguste Racinet. The Costume History (Bibliotheca Universalis), Françoise Tétart-Vittu, Taschen, 2019, ISBN-10: 3836555409

I wanted to describe my undying love for this book, but I’m just gonna copy Taschen’s description: “Racinet’s Costume History is a landmark in the study of clothing and fashion. This reprint presents Racinet’s exquisitely precise color illustrations, as well as his delightful descriptions and witty commentary. From Eskimo attire to high French couture, this is an unrivalled encyclopedia for students, designers, artists, illustrators, and historians, and anyone interested in style.” So, yeah, this 19th century book rules.

Themes: fashion, interior design, furniture, 18th century, 19th century, fashion history, ancient times, middle ages, renaissance, baroque, rococo, victorian, menswear, womenswear.

Available at: Amazon / Taschen

Costume in Detail: 1730-1930, Nancy Bradfield, Quite Specific Media Group Ltd, 1999, ISBN-10: 0896762173

Focused on womenswear, Nancy Bradfield shares with all of us detailed illustrations and descriptions, as well as good information about fashion, garments, shapes, finishings, etc, of extant garments in private collections. A wonderful reference book for reproducing fashion and for illustrations or authors who want to give their character accurate fashion.

Themes: fashion,womenswear, extant garments, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century.

Available at: Amazon / Book Depository

Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the Eighteenth Century, by Harold Koda, Andrew Bolton, Mimi Hellman, Metropolitan Museum of Art 2006, ISBN-10: 0300107145

The book from a long gone exhibition at the Met Museum, it has extant clothes, good info, and the links between fashion and furniture design that make us perceive both as purely 18th century.

Themes: fashion, interior design, furniture, museum collections, extant garments, exhibition, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fashion, A history from the 18th to the 20th century, by Akiko Fukai, Taschen 25th anniversary edition, 2007.

A basic fashion history book starting in the 18th century from the amazing collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute.

Themes: fashion, womenswear, menswear, embroidery, accessories, museum collection, extant garments, England, France, Europe, undergarments, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century.

Available at: Amazon in 1 volume and 2 volumes set.

Gallery of Late-Seventeenth-Century Costume: 100 Engravings, Caspar Luyken, Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN-10: 0486429865

Reprint of a collection of plates by Dutch engraver Caspar Luyken published in 1694. It shows men and women of different social classes and occupations. A key reference when looking for 17th century contemporary source material.

Themes: fashion, menswear, womenswear, Dutch, engraving, plates, 17th century, baroque, late 17th century, contemporary source.

Available at: Amazon / Dover Books

Historic Costumes and How to Make Them (Dover Fashion and Costumes), by Mary Fernald and Eileen Shenton, Dover Publications, 2006, ISBN-10: 0486449068

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century fashion, this book is a nice resource for theatrical costuming and has good but basic bits of historical fashion information. I recommend not to buy with no previous patternmaking and fashion background, since the diagrams are quite vague, and the descriptions even more. I personally only have used this book for reference of Medieval and early Renaissance fashion (which to be fair, are quite simple). Also, it is centered in English fashions.

Themes: fashion, theatre, menswear, womenswear, middle ages, renaissance, tudors, elizabethan, georgian, victorian, 15th century, 16th century, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century.

Available at: Amazon / Barnes and Noble / Dover Publications / Waterstones

How to Read a Dress, A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century, Lydia Edwards, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017, ISBN-10: 1472533275

This books is very pretty and rather basic, it could be a really nice starting point for anyone getting an interest in fashion history. I’ve read reviews that it is “insultingly basic” which I do not get, I mean, if you cannot explain something in such a basic way that a child can get it, then you do not really master that subject. This books has pretty interesting info and it is a walkthrough of key silhouettes and extant garments, so it is not deeply detailed nor shows each and every silhouette of every decade of every century.

Themes: fashion, womenswear, gown, dresses, extant garments, museums, Europe, 16th century, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century.

Available at: Amazon / Bloomsbury

Men's Garments 1830-1900: A Guide to Pattern Cutting and Tailoring, R. I. Davis and William-Alan Landes, Players Press, 1996, ISBN-10: 0887346480

A whole book only for menswear starting with the Regency silhouette and its very particular form until the turn of the 20th century. Yes. It is pretty good, I have to say, for all our Victorian outfit needs for the gentleman. I recommend this book (and the 2nd one on 19th and 20th centuries) for people with some knowledge of construction, grading, fitting, patternmaking, and tailoring, since it does not offer much sewing advice.

Themes: fashion, menswear, accessories, patternmaking, plates, 19th century, 20th century.

Available at: Amazon / Waterstones

Men's Seventeenth & Eighteenth Century Costume: Cut and Fashion, R. I. Davis and William-Alan Landes, Players Press, 2000, ISBN-10: 0887346375

My personal love for menswear is fueled by this book that details the suits, coats and tailcoats from the 17th and 18th centuries. It includes military fashion and other everyday clothes like breeches, capes, waistcoats, etc. via plates, figures, diagrams and texts. I recommend this book (and the 1st one on 19th and 20th centuries) for people with some knowledge of construction, grading, fitting, patternmaking, and tailoring, since it does not offer much sewing advice.

Themes: fashion, menswear, accessories, patternmaking, plates, 17th century, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / Book Depository

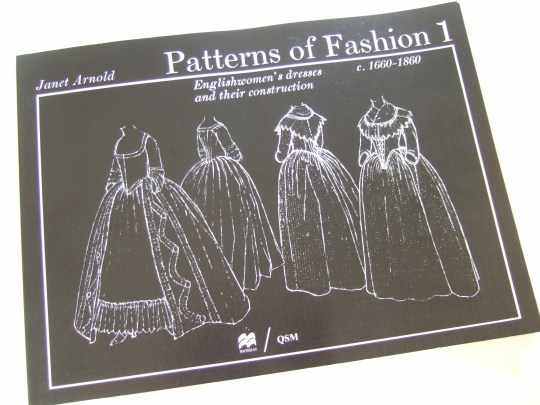

Patterns of Fashion 1: Englishwomen's Dresses and Their Construction C. 1660-1860, by Janet Arnold, Drama Publishers, 2005, ISBN-10: 9780896760264

THE key source of patterns of extant garments, this series of books are the result of constant research on garments from museums, with details and info on construction, history and fashion details. You know, the kind of information you could only get with those garments in your hands.

So, as a resume, in this list there’s only the books with 18th century info in them, BUT you should actually have ALL of the Patterns of Fashion books.

Themes: fashion, womenswear, England, extant garments, museums, Europe, patternmaking, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century.

Available at: Amazon

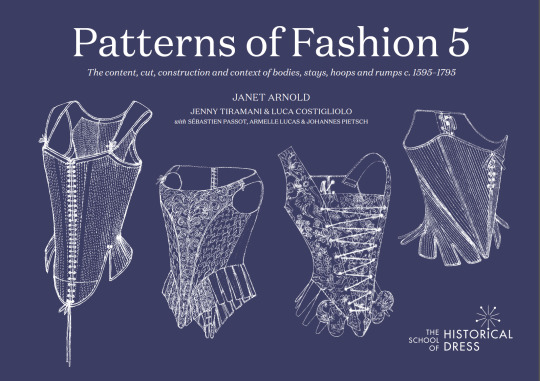

Patterns of Fashion 5: the content, cut, construction & contexto of bodies, stays, hoops & rumps, c 1595-1795, by Janet Arnold, Jenny Tiramani, Luca Costigliolo, Sebastien Passot, Armelle Lucas and Johannes Pietsch, The School of Historical Dress, 2019

The new book from the series is about undergarments from the 16th to the 18th century. It is only available through the store of the School of Historical Dress. Probably the best spent £35.

Themes: fashion, undergarments, stays, womenswear, England, extant garments, museums, Europe, patternmaking, 16th century, 17th century, 18th century.

Available at: The School of Historical Dress

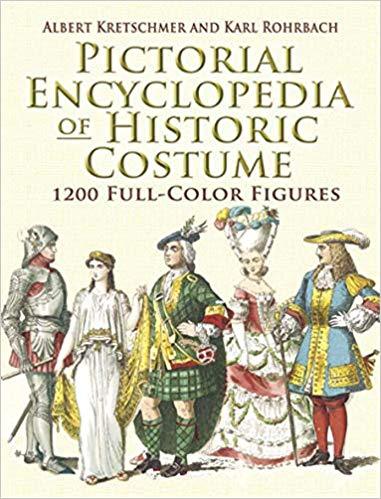

Pictorial Encyclopedia of Historic Costume: 1200 Full-Color Figures, Karl Rohrbach (Author), Albert Kretschmer (Compiler), Dover Fashion and Costumes, 2007, ISBN-10: 0486461424

A reprint of Die Trachten Der Völker from 1906, this book, this is a great great encyclopedic work of fashion history, from ancient Egypt to late 19th century. It includes clothes for people of different social backgrounds, accessories, jewels, shoes, etc. I think that for the fashion history lover, the Rohrbach+Racinet combo is a must.

Themes: fashion, interior design, furniture, 18th century, 19th century, fashion history, ancient times, middle ages, renaissance, baroque, rococo, victorian, menswear, womenswear.

Available at: Amazon / Dover Publications

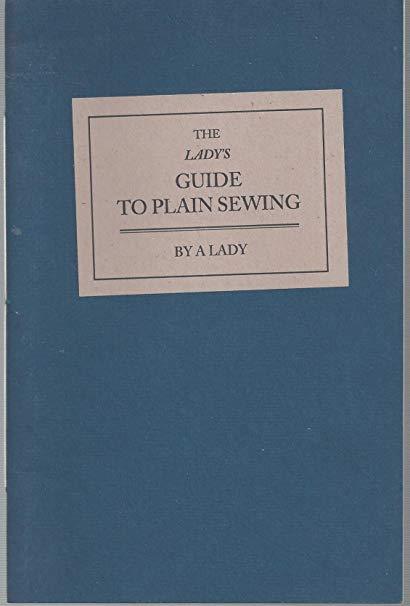

The Lady's Guide to Plain Sewing, Book I, Kathleen Kannik, ISBN 10: 0-9640161-0-9

References and tips for plain hand sewing, a key reference to achieve basic stitches that are historically accurate. It includes basic construction of items and some decorative techniques. Many of these techniques are still used in couture. This book is part 1 of a set of 4.

Themes: fashion, undergarments, womenswear, menswear, sewing, stitches, techniques, how to, patternmaking, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century, couture.

Available at: Kannik’s Korner / Amazon (kindle edition) / Amazon

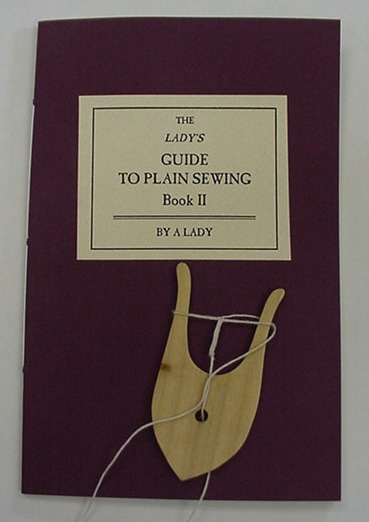

The Lady's Guide to Plain Sewing, Book II, Kathleen Kannik, ISBN 0-9640161-2-5

More sewing stuff with additional stitches and seam techniques, gather attachments, button making, gussets, re-enforcements, cord making, and an 18th century alphabet for cross stitching. This book is part 2 of a set of 4.

Themes: fashion, undergarments, womenswear, menswear, sewing, stitches, techniques, how to, patternmaking, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century, couture.

Available at: Kannik’s Korner / Amazon

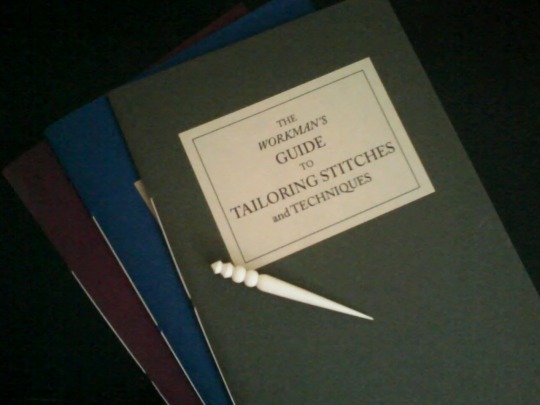

The Workman's Guide to Tailoring Stitches and Techniques, Kathleen Kannik, ISBN 0-9640161-4-1

Now it’s time for historical tailoring stitches and techniques. This book is part 3 of a set of 4.

Themes: fashion, tailoring, menswear, sewing, stitches, techniques, how to, patternmaking, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century.

Available at: Kannik’s Korner / Amazon

The Lady's Economical Assistant or, The Art of Cutting Out, and Making, The most useful Articles of Wearing Apparel, Without waste; Explained by the Clearest directions, and Numerous Engravings, of Appropriate and Tasteful Patterns, ISBN 0-9640161-3-3

A re-drawn publication of a 1808 book, with cutting directions and patterns for infant clothes, girls, boys, some for men and women, and linens. Many illustrations and a supplement. This book is part 4 of a set of 4.

Themes: fashion, undergarments, kidswear, children, babies, infants, womenswear, menswear, sewing, stitches, techniques, how to, patternmaking, 17th century, 18th century, 19th century.

Available at: Kannik’s Korner / Amazon

The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dressmaking: How to Hand Sew Georgian Gowns and Wear Them With Style, by Lauren Stowell and Abby Cox, Page Street Publishing, 2017, ISBN-10: 1624144535

This book is such a good starting point for a 18th century wardrobe, since it walks you through the key outfits of the century in a simple and clear way. I think a background in patternmaking is a plus, especially for the most complex projects, but the basics are easy to follow.

Themes: fashion, patternmaking, how to, womenswear, 18th century.

Available at: Amazon / American Duchess

BEAUTY

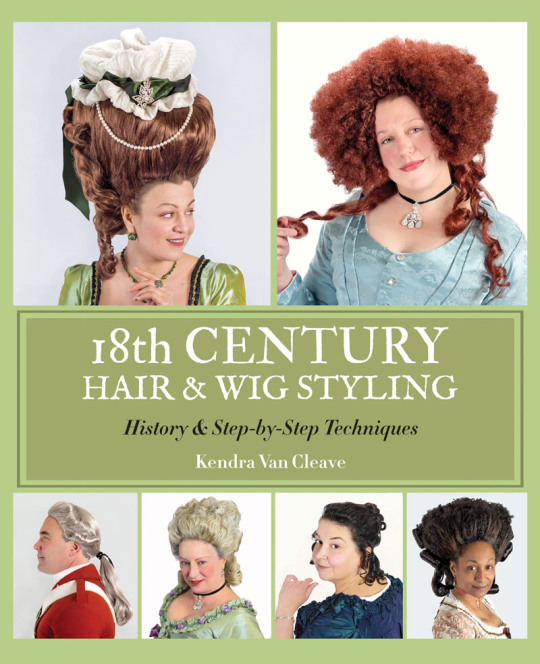

18th Century Hair & Wig Styling: History & Step-by-Step Techniques, Kendra Van Cleave, Nice One, ISBN-10: 0692220437

Kendra van Cleave have been everyone’s guide into the 18th century beauty and hair (and of course, costuming) for quite a long time, thanks to her blog, Démodé, and now she published this well researched book with easy to follow instructions for all kinds of 18th century hairstyles. So, go get your wig and get to work. Also, at the book’s website there some videos, and at her blog you can find even more resources, tutorials, etc.

Themes: fashion, beauty, hair, wigs, 18th century, how to.

Available at: Amazon / 18th Century Hair Website

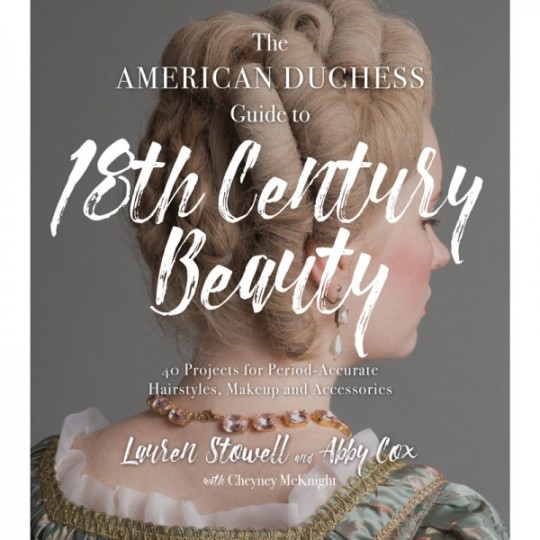

The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty: 40 Projects for Period-Accurate Hairstyles, Makeup and Accessories, by Lauren Stowell and Abby Cox, Page Street Publishing, 2019, ISBN-10: 1624147860

I KNOW this is not available yet, but I think it will be at least as good as the fashion one. Already on my pre-order list, it will be available on July 9th.

Themes: hair, hairstyles, hair and makeup, makeup, accessories, how to, womenswear, 18th century. Available at: Amazon / American Duchess

#sometimes I write stuff#books#my 18th century library#or something#18th century#fashion#history#beauty

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

1700-1739

Continuing my posts of a few decades at a time as I go along.

Previous post: 17th century.

Following posts: 1740-1769, 1770-1799, 1800-1849.

Susanna Hanchett belongs to @desertdollranch; Mazal and Agnes and Charlotte and Jane are my own. Next post finally gets to include some canon characters!

1700s Susanna Hanchett: 46-55 Mazal Cardozo: 26-35 Agnes Jonker: 26-35

Silhouettes are still long and narrow, but they're starting to soften. The frontage is becoming lower and rounder, and the skirts are getting rounder too, with the invention of the pannier, or hoop-petticoat. Even simply-dressed Susanna is starting to let some fullness into her skirts, though I don't imagine she's buying a brand-new, fashionable style of petticoat when she's always made simple ones herself.

1710s Susanna Hanchett: 56-65 Mazal Cardozo: 36-45 Agnes Jonker: 36-45 Charlotte Finch: 0-4 Jane Finch: 0-2

I don't have intro posts for Charlotte and Jane yet. They're my own creations again, mostly because when there's a long while without any new characters I start wondering what I could put there. I don't have stories for them yet, except that they're sisters. I made them rich and fancy purely because I wanted to riff off some extant garments I found online.

1720s Susanna Hanchett: 66-75 Mazal Cardozo: 46-55 Agnes Jonker: 46-55 Charlotte Finch: 5-14 Jane Finch: 3-12

The mantua has morphed from its origins as a casual garment into the more formal option, and in its place fashionable ladies are wearing the big and billowing robe volante, or robe battante, which is a big, loose gown that reminded its critics of a bathrobe. Children's clothes still look a lot like adults', except for their back closures and the aprons. I occasionally drew Charlotte and Jane without aprons, but it looks like that wouldn't have been realistic until they were in their upper teens.

1730s Susanna Hanchett: 76-85 Mazal Cardozo: 56-65 Agnes Jonker: 56-65 Charlotte Finch: 15-24 Jane Finch: 13-22

The robe volante is continuing to morph: the back stays loose, but the bodice is tightening to become the style that will be known as the sack. Skirts are still very round and wide, even for Susanna. For most of her life, Susanna has been wearing simple jacket and petticoat separates, but now those practical garments are coming into vogue. Matching or contrasting casaquin jackets and petticoats are becoming casual wear for women across all income brackets and religious communities. Mantuas are still present as formalwear, but they have a very different silhouette than they did at the beginning of the century: the looped bustle and train is now flattened and pressed, and the petticoat now always matches the mantua.

#American Girl#Zoominag#Susanna Hanchett#Zoominag OCs by AGblr#Mazal Cardozo#Agnes Jonker#Charlotte Finch#Zoominag OCs#Jane Finch#Zoominag by decade

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello! How can i start to sew and then continue to historical sewing? ( i do have a machine )

Hi!

First things first, I am nowhere near an expert, and the bulk of this answer is dedicated to how to find people who are. For example, @vincentbriggs is a great guy to point you towards further resources, especially for menswear and more technical details. His blog even has an FAQ! I also draw a lot of knowledge from the historical sewing community on instagram, many of whom have blogs where they describe their projects in detail, like graciesews and her blog.

here’s something I cannot stress enough: everyone I’ve met so far in the historical sewing community, on- and off-line, is SO NICE. You know how you get a really specific interest, like 1730s opera or the nebulous nature of “violet” in the 17th-18th centuries? And all you want to do is tell someone else all about it but it feels like nobody else really needs it? EVERYONE in the historical sewing community lives that, and wants to tell all they know to a listening ear. (Well, caveat, some people in the reenactment community CAN be really snotty and gate-keepy, but they’re the minority and probably most of them aren’t even on social media because it’s not historically accurate /s. Most people are great. Especially on Instagram. If somebody makes you feel insignificant and bad for asking or just being a beginner, they are in the wrong, not you, and I give you a pass to ignore them with impunity, no matter how expert they are.)

But at the same time, specificity helps, especially when you want to reach out for knowledge from other people. Do you have a set goal in mind, like a specific garment you want to recreate, or a particular type of skill you want to learn? Is there one period you especially love and want to create clothes from? Find people who have done similar projects and see what their process is, what resources they use, etc.

Online tutorials are your friend! I use them probably more than anything. They’ll show you everything from certain obscure stitches to entire garment constructions! For example, I referred almost exclusively to Fresh Frippery’s guide to a Chemise à la Reine when I made my own. And for my bedgown, I used a combination of this and this.

Reading blogs and tutorials by people whose work you admire will not only teach you specific things, it will also give you a new vocabulary of phrases to search for. Someone is making a really cool 1770s gown and mention using English stitch without explaining what it was? Google it! Now you know about a whole new cool stitch. Someone mentions pad stitching? Same thing!

Also learn from extant garments. Lots of museums will have information on the materials used in certain pieces, and books like Colonial Williamsburg’s Costume Close-Up show you how different pieces were constructed, including pattern layouts!

There’s also the question of how deep in the weeds you want to go. Are you interested more in the historical-reenactment-type sewing, in which everything is done to as period-accurate a standard as possible with minimal machine sewing, or something more costuming-oriented, where the lines and shapes are all accurate, but modern techniques and sometimes modern fabrics are used. Both are equally valid and yield wonderful results! For example, fabricatinghistory on Instagram did a cool series of regency garments inspired by Hogwarts Houses, producing a really creative mix of historic lines and modern pop-culture influences (while donating to the Trevor Project at the same time in order to counteract JK’s gross terfiness).

As with all art, every garment you make is practice for the next one. No matter how unpolished your attempt, you learned something important. In several projects I’ve done, I’ve gotten myself into a pickle and have to improvise like heck to get out of it. That’s how I got myself into making an entire embroidered stomacher for my jumps. Every bit of frantic attempts to fix a mistake, or even scrap a garment entirely, is a learning experience that gives you invaluable knowledge for your next project.

For modern sewing, the project that really helped me learn about garment-making was a simple commercial pattern for a pencil skirt I did in high school. It taught me about interfacing, and putting in zippers and fasteners, and was overall a low-stakes way to familiarize myself with all the invisible work that goes into making a garment look right. I transitioned from there into historical sewing fairly quickly, so that’s really where my experience is. I don’t know what modern sewing has got up to since 1820. Let this be an inspiration to you--you can have a boobsworth of knowledge about regular sewing and still learn how to get into historical sewing--that’s p. much what I did!

As far as historical sewing goes, a good intro project is a petticoat. There are lots of tutorials online like this and this. The historic fabric/sewing company Burnley & Trowbridge is also a great source, not only for things to buy at reasonable prices but for historical patterns and even guided kits to make your own garments, like petticoats and aprons and pockets (pockets are great. Once you make a petticoat you WILL want pockets to put things in). On their Facebook and Instagram they also frequently share posts by other costumers in the community, so you can find even more people to learn from!

I don’t know as much about menswear, but I think that as far as those go, a basic 18th-century working-class waistcoat is fairly simple, in my experience (once I paid a talented friend to draft the pattern for me.)

That leads me to perhaps the biggest factor in my sewing: finding people irl who are better at sewing than I am and learning from them. I understand that meeting anyone irl right now is difficult, but if we’re ever able to see people in person again, it’s one thing that really helped me. If you go to school, maybe you won’t have a reenacting club to join like I did, but perhaps there is a cosplay club, or another history-adjacent club like a Jane Austen club that you’re interested and can maybe find people in. But even if you only ever find your people on the internet, they are still excellent resources for learning more. I recognize that joining a college with regular 18th-century sewing circles is a very niche experience.

I’m not sure how much I can tell you re: sewing machines. I rarely use them, as they scare me and also hand-sewing is something I can do on the couch while watching Murder She Wrote. But a machine can be a valuable resource! Something a lot of historical sewists do is machine-stitching the long seams and then hand-finishing the garment. I commissioned a pair of 1780s stays from a friend and they’re almost entirely machine-stitched, but because of how stays are constructed you can barely tell that they differ from a pair of stays hand-sewn with a really good backstitch. And it all depends on what you’re making the garment for--enjoyment/swag or for a reenactment. Standards vary.

This has been all over the place but I hope it helps. We have something in common, you and I. I also feel like a total beginner. When I see other historical sewists display their perfectly dazzling gowns in gorgeous fabrics, both I and my bank account feel the grip of insecurity. I know it’s not a competition, but it sure FEELS like one when my instagram feed looks like an arms race for who can create the most stunning garden-party dress. But it isn’t! You sew for yourself, to show yourself how far you have come in a specific skill and what more you will be able to do in the future. And also you are allowed to say that sometimes sewing is very boring because it is. It is ok to love the product more than the process.

Best of luck! I’m rooting for you, dear anonymous

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cream Embroidered Linen and Silk Robe à l’anglaise, 1725-1750, British.

Met Museum.

#robe à l’anglaise#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#linen#embroidery#British#1725#1720s#1730s#1740s#1720s britain#1730s britain#1740s britain#1720s extant garment#1730s extant garment#1740s extant garment#met museum#1720s dress#1730s dress#1740s dress

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue Silk Robe Volante, ca. 1730, French.

Met Museum.

#blue#silk#robe volante#womenswear#extant garments#dress#french#1730s#1730s France#1730s dress#1730s extant garment#met museum#1730

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Silk Robe à la Française, 1735 (restyled 1770), Possibly Dutch.

MFA Boston.

#beige#Silk#womenswear#extant garments#18th century#Dutch#Holland#1735#1730s#1770s#dress#1730s holland#1770s holland#robe à la française#mfa boston#1730s dress#1770s dress#1730s extant garment#1770s extant garment

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brown Embroidered Silk Dress, 1730-1750, Probably British.

Met Museum.

#brown#embroidery#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#British#1730s#1740s#1730#1730s britain#1740s britain#1730s dress#1740s dress#1730s extant garment#1740s extant garment#met museum

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow Floral Silk Robe à la française Dress, 1730-1750, French.

Met Museum.

#yellow#floral#silk#1730s#1740s#1750s#18th century#met museum#french#France#robe à la française#extant garments#ancien régime#1730s France#1740s France#1750s France#fave#1730s dress#1740s dress#1730s extant garment#1740s extant garment

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pink silk robe volante, 1720-1735.

Palais Galliera.

#1720s#1730s#1720#1720s dress#1730s dress#robe volante#womenswear#extant garments#dress#18th century#palais galliera#pink#silk

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Silk Dress, 1725-1750, American.

MFA Boston.

#beige#womenswear#mfa boston#extant garments#silk#18th century#dress#american#usa#1725#1720s#1730s#1740s#1750s#1720s dress#1730s dress#1740s dress#1750s dress#1720s usa#1730s usa#1740s usa#1750s usa#spitalfields silk#1720s extant garment#1730s extant garment#1740s extant garment

80 notes

·

View notes