#12: If Virginia has powers like Henry's she likely has a sense of how long someone can be tranced before the trancer runs out of energy.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

S4 Victims: Story by Proxy?

Okay so. In spitballing with Em...something stuck in my head.

So we all know how serial killers leave crumbs because deep down they want to be caught/want the truth to be revealed? Well what if the Duffers, or even current Henry, are doing the same thing. That is, leaving breadcrumbs.

This mainly has to do with the S4 victims, their stories, and the order in which they're chosen.

So, it goes like this:

Chrissy: Abusive mother who resembles Virginia

Fred: Eaten alive by the guilt of being responsible for the accidental death of an innocent.

Max: Suicidal over guilt about Billy's death and her response to it. Billy, who died saving her/while she was saving herself from the Fleshflayer, a regenerated form of the Mindflayer.

Patrick: Abusive father, not much else told.

Max (again): Suicidal Ideation, dies, soul taken, but was revived by El. She's now in some limbo-state, where her body lives but her identity/mind is elsewhere. She will likely be brought back entirely by El in S5.

It almost feels like a story by proxy if we piece it together.

So, let's piece it together:

Person with an abusive mother...feels responsible for the death of an innocent...a sibling who was killed while this person was trying to save themselves from a monster which came from Hawkins lab, which leaves them suicidal...and this person lives in a situation with an abusive father figure. This person becomes suicidal, and their suicide attempt was not entirely successful. They were revived by El, and end up in a limbo state. They may or may not be brought back by El later.

Now, let's collect details about our serial killer:

Abusive mother? Check. (No matter how we frame it, Virginia was not a good mother.)

Innocent died? Check. (Henry has nothing bad to say about Alice, which we know he would if she were not innocent, since he does this with every other victim.)

Sibling died as a result of saving oneself? Check. (The Creel massacre was a situation where Henry was, with whatever intentions we may assign for the other family members' deaths, trying to save himself from Virginia and by extension the lab.)

Ended up with an abusive father figure? Check. (Well...an abusive Papa, one might say.)

Brought back by El multiple times? Check. (El was the one who took Soteria out and brought Henry back from being powerless. El was the one who put Henry in the UD/limbo state. El was the one who opened the gate for his return to the RSU.)

IT ALL ALIGNS. So let's put it together with all the feelings involved:

Citations (I guess? Explanations?) are in the tags listed by number!

Henry had an abusive mother who was at least trying to have him shipped off to the lab, if not actually trying to kill him outright. This situation builds and builds, him wanting to be left alone (1), putting out subconscious and conscious cries for help (2), and her targeting him about it, until March 25th, 1959.

Virginia starts it, attacks, and this time she's out for blood (3). Henry defends himself (4). Virginia, being the parent with powers (5), doesn't actually die (6). Victor, Alice, and Henry go for the door (7). Virginia's on the stairs (8). She's got to finish what she started, since her original plan was botched (9). Henry puts his energy into trancing Victor (10), protecting him from Virginia, since logically two people can't occupy one person's mind.

This leaves good, innocent Alice to fend for herself, standing directly in front of the staircase. She's a loose end (11). Virginia kills her, but can't kill Henry or Victor while the trance is occurring. She figures Henry's going to run himself into the ground (12). She figures she can call Brenner in to collect Henry, like they planned (13). If she disappears, she figures it'll go into the news something like this:

"World War II veteran kills entire family in deranged fit of insanity. Wife missing, presumed dead. Son dies in hospital."

And on both counts, she's essentially right. It does basically go into the papers that way. Victor is taken in for murder, and Henry is taken by Brenner, but not before he sees that Alice was caught in the crossfire (14).

Henry ends up with Brenner, the abusive Papa. He's got the guilt about Alice's death, something that makes him sad and angry. Brenner, maybe, decides to push this in order to increase Henry's powers, but it backfires. Henry's powers increase, but he does...something. He lashes out, he snaps, maybe he even tries to kill himself. He's Brenner's prized pet, though, so Brenner can't let that happen. He seals Henry's powers away with Soteria. It's a death for Henry's entire identity, so far as to have him under the name Peter Ballard. Then comes along 011. She removes Soteria from Peter Ballard...and revives Henry Creel. She then exiles him to the Upside Down in 1979, only to eventually bring him back in 1983 when she opens the Mothergate.

All this to say: It could be his own story, told through the stories of his victims.

Breadcrumbs, or maybe...obvious things, which nobody by any chance ever observes.

Below the cut is where I speculate into motivations for his actions after Soteria's removal, so...not required reading for this particular analysis.

Years of MKUltra torture warp Henry's guilt about the situation into a bastardized, violent, brutal, unethical savior complex based in the notion that he's a predator by nature, but a predator for good. He "saves" the lab kids from a future like his own, filled with nothing but torture. He "saves" El from her ignorance about the lab and intended to have her join him, thereby attempting to "save" her, technically his little sister, from the lab entirely.

He "saves" his s4 victims from their guilt and suffering, which so closely mirror his own, which no one saved him from. I could even go so far as to say he was "saving" Will, who is set up to be so much like him, from a world of horrible people who (from Henry's viewpoint based on his lived experiences) would only serve to abuse and betray him.

This of course isn't to say any of it is right. None of it is right or good...but it makes sense. It follows a pattern. It coheres. The math...maths.

#Citations!#1: Henry often hides alone in the attic.#2: Victor's burning cradle vison (a child in need of help). The drawing of the Shadow Monster. Possibly Alice's nightmares.#2 (cont.): Can all be interpreted as calls for help. Children in distress act out and make disturbing art in hope of conveying that need.#3: Virginia may or may not have been trying to kill Henry but based on the Fleshflayer parallel re: sibling death...it's probable.#4: Henry himself describes that night as self defense/being forced to act.#5: Virginia likely had powers given that Henry has powers#6: Her powers are likely similar to Henry's and Henry has regenerative powers. There are also fishy scenes of her death which imply#6 (cont.): that she may have still been alive. These include: shots from her POV. The fact that her eyes are bloody--#6 (cont.): but still intact in some shots. The unexplained POV from the top of the stairs.#7: Henry looks very nervous and fidgety at the door like he's antsy to leave with Alice and Victor#8: Again the unexplained POV on the stairs...stairs she earlier runs down after Henry gives her her mirror moment in the bathroom.#9: Henry was successful in disabling her initially which exposed her culpability.#10: Henry puts *so* much time into Victor in canon with basically no explanation why.#11: Alice seems to be a smart and upstanding girl. She might not be controllable re: Virginia being alive/the whole scheme with Brenner.#11 (cont.): The only way to eliminate that risk is to kill her...and we've already seen that Virginia is not good to at least one child.#12: If Virginia has powers like Henry's she likely has a sense of how long someone can be tranced before the trancer runs out of energy.#13: Who called Brenner to come get Henry during his coma? How did Henry end up in Brenner's hands specifically?#14: amerion-main's recent post re: Henry's position change in the foyer shots#End Citations!#This is all very much speculation when it comes to the actual path of events re: the Creel Massacre#but we can all agree that we don't have the full story about the Creels yet...so who knows.#henry/vecna/001#henry creel analysis#henry creel#virginia creel#creel family#stranger things#stranger things analysis

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

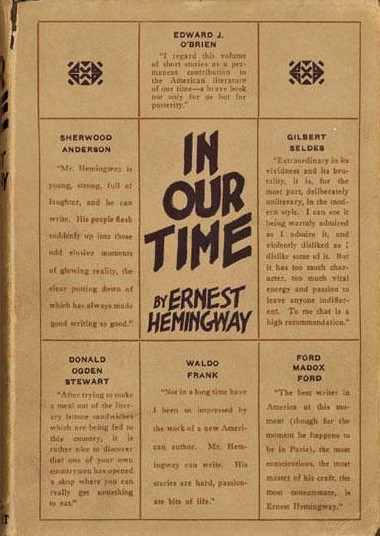

The greatest year for books ever?

Several years including 1862, 1899 and 1950 could be considered literature’s very best. But one year towers above these, writes Jane Ciabattari.

The year 1925 was a golden moment in literary history. Ernest Hemingway’s first book, In Our Time, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby were all published that year. As were Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer, Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith, among others. In fact, 1925 may well be literature’s greatest year.

But how could one even go about determining the finest 12 months in publishing history? Well, first, by searching for a cluster of landmark books: debut books or major masterpieces published that year. Next, by evaluating their lasting impact: do these books continue to enthrall readers and explore our human dilemmas and joys in memorable ways? And then by asking: did the books published in this year alter the course of literature? Did they influence literary form or content, or introduce key stylistic innovations?

Books that came out in 1862, for instance, included Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. But Gustave Flaubert’s novel of that year, Sallambo, set in Carthage during the 3rd Century BC, was no match for Madame Bovary. George Eliot’s historical novel Romola and Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm were also disappointments.

The year 1899 is another contender for literature’s best. Kate Chopin’s seminal work The Awakening was published then, as was Frank Norris’s McTeague and two Joseph Conrad classics – Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim (serialised in Blackwood’s Magazine). But Tolstoy’s last novel Resurrection, published also in 1899, was more shaped by his religious and political ideals than a powerful sense of character; and Henry James’ The Awkward Age was a failed experiment – a novel written almost entirely in dialogue.

And in 1950 there were published books from Isaac Asimov (I, Robot), Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles), Patricia Highsmith (Strangers on a Train), Doris Lessing (The Grass Is Singing) and CS Lewis (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe). But other great fiction writers produced lesser works that year – Ernest Hemingway’s minor Across the River and into the Trees; Jack Kerouac’s The Town and the City, written under the influence of Thomas Wolfe; John Steinbeck’s poorly received play-in-novel-format Burning Bright and Evelyn Waugh’s only historical novel, the Empress Helena (Roman emperor Constantine’s Christian mother goes in search of relics of the Cross).

But 1925 brought something unique – a vibrant cultural outpouring, multiple landmark books and a paradigm shift in prose style. Literary work that year reflected a world in the aftermath of tremendous upheaval. The brutality of World War One, with some 16 million dead and 70 million mobilised to fight, had left its mark on the Lost Generation. In Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf created the indelible shell-shocked veteran Septimus Smith, “with hazel eyes which had that look of apprehension in them which makes complete strangers apprehensive too. The world has raised its whip; where will it descend?”

Looking inward

The solid external world of the realists and naturalists was giving way to the shifting perceptions of the modernist ‘I’. Mrs Dalloway, which covers one day as Clarissa Dalloway prepares for a party – and Septimus Smith for his demise – is a landmark modernist novel. Its narrative is rooted in the flow of consciousness, with dreams, fantasies and vague perceptions gaining unprecedented expression. Woolf’s stylistic breakthrough reflected a changing perception of reality. Proust was also all the rage at this moment, as Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Remembrance of Things Past’s third volume was just out. Woolf admired Proust’s “astonishing vibration and saturation and intensification”.

The year 1925 also contributed to the culmination of Gertrude Stein’s career. She had moved to Paris in 1903 and established a Saturday evening salon that eventually included Ernest Hemingway, F Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, Ezra Pound and Sherwood Anderson, as well as artists Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Stein responded to her immersion in the Parisian avant-garde by writing The Making of Americans, which was published in 1925, more than a decade after its completion. In over 900 pages of stream-of-consciousness, Stein tells of “the old people in a new world, the new people made out of the old,” and describes an American “space of time that is filled always filled with moving”. Early critics like Edmund Wilson couldn’t finish Stein’s complex web of repetition, but she has been credited with foreshadowing postmodernism and making key stylistic breakthroughs, including using the continuous present and a nearly musical word choice. As Anderson put it: “For me, the work of Gertrude Stein consists in a rebuilding, an entirely new recasting of life, in the city of words.”

Stein’s experiments with language influenced Hemingway’s signature sparseness. Beginning with the autobiographical Nick Adams stories in his first book, 1925’s In Our Time, his fiction is characterised by pared-down prose, with symbolic meaning lying beneath the surface. Nick witnesses birth and suicide as a young boy accompanying his father, a doctor, to deliver a baby in the Michigan woods. He is exposed to urban crime when two Chicago hitmen come to his small town. And as a war veteran trying to keep his memories at bay, he gravitates toward the familiar pleasures of camping and fishing: "He had made his camp. He was settled. Nothing could touch him."

Modern times

The midpoint of the Roaring ‘20s was a time of rare prosperity and upward mobility in the United States. The stock market seemed destined to climb forever, and the American Dream seemed within the grasp of the masses. 1925 was special, though. In New York, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer and other writers of the Harlem Renaissance were given a definitive showcase that year in the anthology The New Negro, edited by Alain Locke. At the same time Harold Ross launched a revolutionary and risky weekly magazine called The New Yorker, which featured portraits of Manhattan socialites and their adventures and offered what would be a treasured showcase for short stories ever since.

F Scott Fitzgerald dubbed this flamboyant postwar American era “the Jazz Age”. Alcohol flowed freely despite Prohibition; flappers followed the sober suffragettes into a time of sexual freedom. New wealth was spreading the riches and opening doors to players like Fitzgerald’s immortal character Jay Gatsby, whose fortune was rumoured to be based on bootlegging. The Great Gatsby, published in 1925, gives a portrait both tawdry and touching, as Gatsby remakes himself in a doomed attempt to win the love of the wealthy Daisy Buchanan. The tarnished American Dream also was central that year to Theodore Dreiser’s naturalist masterpiece, An American Tragedy. Dreiser based the novel on a real criminal case, in which a young man murders his pregnant mistress in an attempt to marry into an upper class family, and is executed by electric chair. Also ripped from the headlines, Sinclair Lewis’s realistic 1925 novel Arrowsmith was a first in exploring the influence of science on American culture. Lewis wrote of the medical training, practice and ethical dilemmas facing a physician involved in high-level scientific research.

These books weren’t just original, even revolutionary, creations – they were helping to establish the very idea of modernity, to make sense of the times. Perhaps 1925 is literature’s most important year simply because no other 12-month span features such a dialogue between literature and real life. Certainly that’s the case in terms of how new technologies – the automobile, the cinema – shook up literary form in 1925. John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer introduced the cinematic narrative form to the novel. New York, presented in fragments as if it were a movie montage on the page, is the novel’s collective protagonist, the inhuman industrialised city presented as a flow of images and characters passing at high speed. "Declaration of war… rumble of drums... Commencement of hostilities in a long parade through the empty rain lashed streets,” Dos Passos writes. “Extra, extra, extra. Santa Claus shoots daughter he has tried to attack. Slays Self With Shotgun." Sinclair Lewis called Manhattan Transfer "the vast and blazing dawn we have awaited. It may be the foundation of a whole new school of fiction."

Was 1925 the greatest year in literature? The ultimate proof, 90 years later, is the shape-shifting the novel has undergone, still based on these early inspirations – and the continuing resonance of Nick Adams, Jay Gatsby and Clarissa Dalloway. These characters from a transformative time are still enthralling generations of new readers.

Copyright © 2020 BBC

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I’ve read in 2019!

2017 2018

Hello! Welcome back to the appointment I’m sure every one of you was waiting since last year (heavy sarcasm)! Fasten your seat belts, it’s gonna be a long ride..

THE MASTER AND MARGARITA, Michail Bulgakov - one of the greatest books I’ve ever read, it has become one of my favourites in a few chapters; I loved the characters, out of their minds the lot of them, I loved this Devil, so nice and generous; I mostly loved the completely natural way with which Bulgakov tells absurd facts; a comedy, but much more than that too. 9.5/10

HEART OF A DOG, Michail Bulgakov - I’m in awe at his style, he’s different from other russian authors; it’s problavly the irony, the grotesque characters, the unusual portrait of life in Moscow after the revolution; I don’t know, but I love it; this book was one weird experience, but I wasn’t really surprised. 8.5/10

THE WAVES, Virginia Woolf - is it a dialogue? is it a pure flow of thoughts? sometimes it seems they’re talking to each other, sometimes it seems everyone’s just thinking by themselves, sometimes it seems both and neither; one moment everything is beautiful, the next life is a horrible mess; is it a novel? I don’t know, it all felt like one big poem and I loved every minute of it. 10/10

NORTHANGER ABBEY, Jane Austen - one of the most frustrating books I've ever read, but I really really liked it; the characters are some various degrees of DRAMA and it’s honestly hilarious to watch; for me, it had the bonus of an unexpected final, idk why really, but I thought it would end differently; cute and so aesthetically pleasing as usual. 7/10

THE BOOK OF DISQUIET, Fernando Pessoa - very well written, I love how each sentence is built and the rhytm of it all, but there’s a hopelessness in the background and maybe I was relating overly, but I don’t want to think too much about what this book says. 8/10

THE BELL JAR, Sylvia Plath - I felt angry with every single character and I don’t like feeling so much while I read a book. I liked it tho, even if I honestly don’t know why. It almost feels wrong to like this book. It got me out of the slump I found myself in during summer screaming and kicking, and I can’t forget that. 8/10

FRANKENSTEIN, Mary Shelley - I’m in awe at the fact that she wrote this book when she was 19; it was everything I thought it’d be, and more. I could find no sympathy for the creature, nor for Viktor (he is so stupid); the atmosphere was heavy, dark, and as miserable as every character (except Henry, poor baby boy I love him), it felt absolutely perfect. 9/10

DRACULA, Bram Stoker - where to begin.. the first 12 or so chapters were very, very, slow, and the style was a bit tiring to me, with all those diaries and notes. BUT, except for that and the vague misogyny that comes out at times, IT IS a great book, a great horror. I loved the Count, finally a villain who’s evil just because, and Mina too, when she wasn’t occupied wondering at how amazing men are and how little women deserve them. She’s never the damsel in distress waiting to be saved, she’s almost more the knight in shining armour.. I’ll shut up, I loved it. 8/10

MADAME BOVARY, Gustave Flaubert - I thought only Wuthering Heights could have had characters so unbearable, but turns out I was wrong. There isn’t a single good person in this book, everyone is either an asshole or a hopeless idiot.. it’s a tragedy, it actually reminded me of Shakespeare, in a sense; everything could be easily solved if people would just talk to eachother. I honestly don’t know if I liked it, it had potential but was a bit boring, it mostly made me angry. 6/10

PARADISE LOST, John Milton - I was probabli in the wrong mood for this, it was November after all, and I must say, it bored me to no end. Really, it didn’t leave me anything except a great relief when I read the last words. I liked a lot the parts where the author spoke, I recoiled every time the others had a dialogue (except, maybe, surprisingly or not, for Satan)... growing up as a woman in a christian family does this to one I guess. 5/10

THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV, Fëdor Dostoevskij - to be honest, I’m posting this without having finished the book, I still have five chapters or so to read, but I don’t have a doubt when I say: I love it. Idk if it’s the AMAZING, INCREDIBLE job the translator(s?) have done but this story goes on so smoothly, not once I felt bored, not once I felt uncomfortable with the style, not once I felt like I wasn’t fully understanding what was going on. It’s so well written that at times I had the impression of being inside the head of the characters, like I was the characters. Idk I haven’t felt like this in a very long time, I knew how he wrote, I’ve read others of his books, but it still caught me by surprise and I can’t say I’m not delighted by it. 10/10

Theatre & Short Stories

THE WINTER’S TALE, William Shakespeare - it was weird, it put me in such an anxious state, at some point I thought everything was going to end in tragedy; my man never cease to surprise me. 8/10

TITUS ANDRONICUS, William Shakespeare - ok..so... I was angry with everyone, I couldn’t feel any sympathy for anyone, except for Lavinia; I honestly don’t know what William was thinking, I don’t know if I should love it or be horrified by it... complete madness it is. 9/10

MEASURE FOR MEASURE, William Shakespeare - let’s say, I’ve always preferred the tragedies, but, as Ju once wisely said, women in Billy’s comedies are simply great; that’s true even in this, Isabella is amazing while everyone else is just.. meh... I can’t shake off the feeling that mr.Duke was bored and decided to cause some useless drama, it’s all very shakesperean. 7/10

THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH, Edgar Allan Poe - do you need a short tale to tell at sleepovers? Do you need a horror story for Halloween night? This is perfect. Short, to the point, fast and terrifying.. or maybe that’s just me and my fear of pendulum clocks lol. 7/10

Poetry

Emily Dickinson - at some points it bored me, at some others I had to stop reading to take a few steading breaths; lovely and so powerful. 8/10

Edgar Allan Poe - not a fan of the man himself, but his poetry is just my kind, you know? it’s so full of love and darkness; I love the rhymes, I love the rhythm. idk, I liked it a lot. 8,5/10

#books#books ive read in 2019#book recs#bookish advices#booklr#bookworm#booklover#literature#poetry#theatre#classics#the hard life of a bookaholic#reading#long post#michail bulgakov#virginia woolf#jane austen#fernando pessoa#sylvia plath#mary shelley#bram stoker#gustave flaubert#john milton#fedor dostoevskij#william shakespeare#e.a. poe#emily dickinson#laemontalks

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

September Reads!

Sooooo, who’s 12 days late to show all the books I read last month?

This bitch!

So here’s how I decided to do this end of the month wrap ups. I’m going to add a read more, give the back of the book summary, my snap thoughts, and then a rating. That way, if you don’t care for long posts you don’t have to suffer.

You’re welcome.

The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

A young FBI trainee. An evil genius locked away for unspeakable crimes. A plunge into the darkest chambers of a psychopath’s mind- in the deadly search for a serial killer. . . .

Thoughts: MMMM yes, this is the good shit. Hell to the bells yes. This is my shit. One of my faves. Top ten books read ever.

Rating: 10/10 would recommend

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

The Road is a profoundly moving story of a journey. It boldly imagines a future in which no hope remains, but in which a father and his son, “each the other’s world entire”, are sustained by love.

Thoughts: Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. This book is rough. This world is absolutely horrifying but the relationship that McCarthy crafts between the father and son is so emotional. I have heard that this is one of McCarthy’s least rough books to read in both emotional trauma and philosophical nihilism. (Also I think there was a Jesus allegory in the son. I don’t know why but it felt like he was the future religion. Look, I was too busy crying. I don’t think I could handle reading another McCarthy, alright?)

Rating: 4/10 I didn’t really like it but I think it’s like Pulp Fiction. Everyone should read it once.

The Beguiled by Thomas Cullinan

Wounded and near death, a young Union Army corporal is found in the woods of Virginia during the height of the Civil War and brought to the nearby Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies. Almost immediately he sets about beguiling the three women and five teenage girls stranded in this outpost of Southern gentility, eliciting their love and fear, pity and infatuation, and pitting them against one another in a bid for his freedom. But as the women are revealed for who they really are, a sense of ominous foreboding closes in on the soldier, and the question becomes: Just who is the beguiled?

Thoughts: This is one of those books that I came into with high hopes. The story itself was good. I liked the overall story. I was not fond of the writing style. It’s the 1960′s trying to emulate the 1860′s. Overall, it went over like a lead balloon.

Rating: 5/10 Take it or leave it. You’ll either like it or you wont. (Check it out at the library.)

The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson

It’s the summer of 1854, and London is seized by a violent outbreak of cholera that no one knows how to stop. As the epidemic spreads, a maverick physicians and a local curate are spurred to action, working to solve the most pressing medical riddle of their time. Ina a triumph of multidisciplinary thinking, Johnson illuminates the intertwined histories of the spread of disease, the rise of cities, and the nature of scientific inquiry, offering both a thrilling account of the most intense cholera outbreak to strike Victorian London and a powerful explanation of how it has shaped the world we live in.

Thoughts: I loved this. I know that history can be dry and dull but this had a dynamic way of speaking about the past. The writer is a journalist not a “true” historian so it makes for good reading. No shade, but many historians just write like dust. Sooo dry. Mmm, book good, much education. I feel illuminated.

Rating: 9/10 would recommend

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann

In the 1920s, the richest people per capita in the world were members of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma. After oil was discovered beneath their land, they rode in chauffeured cars and lived in mansions.Then one by one, the Osage began to be killed. Mollie Burkhart watched as her family became a prime target. Her relatives were shot and poisoned. Other Osage were also dying under mysterious circumstances, and many of those who investigated the crimes were themselves murdered. As the death toll rose, the case was taken up by the newly created FBI and its young, secretive director, J. Edgar Hoover. Struggling to crack the mystery, Hoover turned to a former Texas Ranger named Tom White, who put together an undercover team, including a Native American agent. They infiltrated this last remnant of the Wild West, and together with the Osage began to expose one of the most chilling conspiracies in American History.

Thoughts: This is a book that will make your blood boil. It shows the blatant racism with an unapologetic stare. As an Irish Cherokee living in Oklahoma, I was biting my fist in rage throughout this entire book. These crimes, these absolutely disgusting crimes should be taught in history books. If you have no idea what this is about. Read the damn book. If you have an idea of the events. Read the damn book. If you live in Europe. Read the damn book. Events like this should never be forgotten. And God bless Mollie Burkhart. Read the book and you will feel that way too. Just read the book.

Rating: 10/10 read the damn book

The Circle by Dave Eggers

When Mae Holland is hired to work for the Circle, the world’s most powerful internet company, she feels she’s been given the opportunity of a lifetime - even as life beyond the campus grows distant, even as a strange encounter with a colleague leaves her shaken, even as her role at the Circle becomes increasingly public. What begins as the captivating story of one woman’s ambition and idealism soon becomes a heart-racing novel of suspense, raising questions about memory, history, privacy, democracy, and the limits of human knowledge.

Thoughts: Holy shit. This is why I don’t own a smart phone. Read this book and you will second glance at every piece of technology that you own. In thrillers I try to guess what is going to happen and I was wrong about the ending of this book. Which, to tell the truth, made me happy but I was paranoid about the ending. Like it feels like life is moving towards this kind of universe and I don’t like it. May I just say that I am Mercer.

Rating: 8/10 would recommend

Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich

On April 26, 1986, the worst nuclear reactor accident in history occurred in Chernobyl and contaminated as much as three quarters of Europe. Voices from Chernobyl is the first book to present personal accounts of the tragedy. Journalist Svetlana Alexievich interviewed hundreds of people affected by the meltdown - from innocent civilians to firefighters to those called in to clean up the disaster - and their stories reveal the fear, anger, and uncertainty with which they still live. Comprised of interviews in monologue form, Voices from Chernobyl is a crucially important work, unforgettable in its emotional power and honesty.

Thoughts: This book will take you through every possible emotion known to man kind. Alright. Do not read this if you are in an emotionally compromised state. It will make it worse. That said, I truly believe that this is a pivotal piece to understand the Chernobyl disaster from the ground up instead of the top down view that much of the western world understands. Also, with that Chernobyl series this seems an apropos time to read this.

Rating: 9/10 Everyone should read this once.

Reading Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi

Every Tuesday mornign for two years in the Islamic Republic of Iran, a bold and inspired teacher named Azar Nafisi secretly gathered seven of her most committed female students to read forbidden Western classics. As Islamic morality squads staged arbitrary raids in Tehran, fundamentalists seized hold of the universities, and a blind censor stifled artistic expression, the girls in Azar Nafisi’s living room risked removing their veils and immersed themselves in the worlds of Jane Austen, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, and Vladimir Nabokov. In this extraordinary memoir, their stories become intertwined with the ones they are reading. Reading Lolita in Tehran is a remarkable exploration of resilience in the face of tyranny and a celebration of the liberating power of literature.

Thoughts: You know a book that makes you frustrated with the author when they did something you know that they would regret in the past? I felt that. I won’t spoil it but I did say on multiple occasions “You asked for this!” This book is living proof of the old adage “Be careful what you wish for, you just might get it.” Yeah, that’s what I felt and pity. There was some pity going on.

Rating: 8/10 Read it if you are interested in Middle Eastern history or women’s studies. I don’t think it’s everyone’s cup of tea.

The Perfect Girlfriend by Karen Hamilton

Juliette loves Nate. She will follow him anywhere. She’s even become a flight attendant for his airline so she can keep a closer eye on him. They are meant to be. The fact that Nate broke up with her six months ago means nothing. Because Juliette has a plan to win him back. She is the perfect girlfriend. And she’ll make sure no one stops her from getting exactly what she wants. True love hurts, but Juliette knows it’s worth all the pain. . .

Thoughts: This book is an easy read. It’s a day and a half for someone who reads a lot. Easy to get into, easy to understand, but it doesn’t act like it thinks you’re stupid. Creepy in the same way You was creepy. If you liked You you will like this book. If stalkers aren’t your thing avoid this one. I will say that I found the ending underwhelming. It felt like the author was tired of writing and just wanted to end the freaking book. Other than that, it was fine.

Rating: 6/10 Like You? Read this one.

The Trial of Lizzie Borden by Cara Robertson

When Andy and Abby Borden were brutally hacked to death in Fall River, Massachusetts, in August of 1892, the arrest of the couple’s daughter Lizzie turned the case into international news and her trial into a spectacle unparalleled in American history. Reporter flocked to the scene. Well-known columnists took up conspicuous seats in the courtroom. The defendant was relentlessly scrutinized for signs of guilt or innocence. Everyone - rich and poor, suffragists and social conservatives, legal scholars and laypeople - had an opinion about Lizzie Borden’s guilt or innocence. The popular fascination with the Borden murders and its central, enigmatic character has endured for more than a hundred years, but the legend often outstrips the story. Based on transcripts of the Borden legal proceedings, contemporary newspaper articles, previously withheld lawyer’s journals, unpublished local reports, and recently unearthed letters from Lizzie herself, The Trial of Lizzie Borden is a definitive account fo the Borden murder case and offers a window into America in the Gilded Age, showcasing its most deeply held convictions and its most troubling social anxieties.

Thoughts: I have always been fascinated with this case. It is one of the first nationally publicized cases and as such everyone knew. Can you imagine never being able to go anywhere without being recognized as the one woman who got away with murder? In America we still sing “Lizzie Borden took an axe, gave her mother forty whacks. When she saw what she had done, gave her father forty-one.” No one alive in America doesn’t know who Lizzie Borden is. If you like true crime and history you will like this. I think you probably would even if you aren’t a connoisseur of those genres. P.S. I still think Lizzie did it.

Rating: 9/10 would recommend

Jane Austen, the Secret Radical by Helena Kelly

An illuminating reassessment of the life and work of Jane Austen that makes clear how Austen has been misread for the past two centuries and how she intended her books to be read. In Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, Helena Kelly, dazzling Jane Austen authority, looks a the writer and her work in the context of Austen’s own time to reveal this popular, beloved artist as daring, even subversive in reaction to her roiling world and to show, novel by novel, how Austen imbued her books with radical, sometimes revolutionary ideas - on slavery, poverty, feminism and marriage as trapping women, on the Church, and evolution. We see that Austen was writing in a time when revolution was in the air (she was born the year before the American Revolution; the French Revolution began when she was thirteen). England had become a totalitarian state; Britain was at war with France. Habeas corpus had been suspended; treason, redefined, was no longer limited to actively conspiring to overthrow and to kill. It now included thinking, writing, printing, and reading (Tom Paine was convicted of seditious libel in 1792 for ideas considered dangerous to the state), the intention being to pressure writers and publishers to police themselves; those who criticized the government or who turned away from the Church of England were seen as betraying their country in its hour of need. In this revelatory, brilliant book, Kelly discusses each of Austen’s novels in the order in which they were written. Whether writing about the fundamental unfairness of primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility (influenced by Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Women) or about property and inheritance, war, revolution, and counterrevolution in Pride and Prejudice (Kelly describes the novel as a revolutionary fairy tale written in response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France) or about Mansfield Park, with its issues of slavery and the hypocrisy of the Church of England, we see Austen not as someone creating a procession of undifferentiated romances but as someone whose novels reflect back to her readers the world as it is - and was then - complicated, messy, and filled with error and injustice. We see a writer who understood that the novel - seen as mindless “trash” - could be a great art form and who, perhaps more than any other writer up to that time, imbued it with its particular greatness. And finally we see Austen - the writer; the artist; the serious, ambitious, clear-sighted woman “of information” - fully aware of what was going on in the world around her, clear about what she thought of it, and clear that she set out to write about it and to quietly, artfully make her ideas known.

Thoughts: Damn that synopsis. Advice for publishers: create an engaging synopsis in one to three paragraphs. That being said this was a fascinating read. I love Austen so I enjoyed having more context to the stories. Great for women’s studies, english literature and a perspective of slavery rarely mentioned (at least in my readings).

Rating: 9/10 will enjoy if you enjoy Austen

#books#literature#end of the month#jane austen#lizzie borden#chernobyl#cormac mccarthy#thomas harris#clarice starling#hannibal lecter

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

House Passes Bill to Raise Minimum Wage to $15, a Victory for Liberals

The current federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour — about $15,000 a year for someone working 40 hours a week, or about $10,000 less than the federal poverty level for a family of four, and has not been raised since 2009. According to a Congressional Budget Office study, raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2025 will pull 1.3 million American out of poverty and could result in wage increases for up to 27 million workers. But it would leave 1.3 million people, or 0.8 percent of the work force, out of a job, the same study concluded. Should the federal government gradually increase the minimum to $15 an hour by 2025: (1) Yes, (2) No? Why? What are the ethics underlying your decision?

The House voted Thursday to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025, delivering a long-sought victory to liberals and putting the Democratic Party’s official imprimatur on the so-called Fight for $15, which many Democratic presidential candidates have embraced.

The bill would more than double the federal minimum wage, which is $7.25 an hour — about $15,000 a year for someone working 40 hours a week, or about $10,000 less than the federal poverty level for a family of four. It has not been raised since 2009, the longest time the country has gone without a minimum-wage increase since it was established 1938.

The measure, which passed largely along party lines, 231-199, after Republicans branded it a jobs-killer, faces a blockade in the Senate, where Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader, said he will not take it up. Only three Republicans voted for it, while six Democrats opposed it. Most represent swing districts.

But it previews what Democrats would do if they capture the Senate and the White House in 2020, and it demonstrates how fast the politics have shifted since 2012, when fast-food workers began to strike in cities around the country, demanding $15-an-hour wages and a union.

When the Fight for $15 movement was launched, the figure seemed absurdly high, and even Democrats thought it was politically impossible. In the years since, even Republican states like Arkansas and Missouri have raised minimum wages, encouraging Democrats on Capitol Hill. In 2016, Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, pushed the issue to the fore when he challenged Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination.

“This is an historic day,” declared Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who argued that raising the minimum would disproportionately help women, who make up more than half of minimum wage workers, and would particularly help women of color. Turning to Republicans, she said: “No one can live with dignity on a $7.25-per-hour minimum wage. Can you?”

As the measure passed, the House gallery, filled with restaurant workers, erupted into cheers and chants of “We work! We sweat! We want 15 on our check!”

“It’s got overwhelming support within the Democratic Caucus, and I think the fact that it could pass in Arkansas gives pause to anybody that’s thinking about voting against it,” said Representative Robert C. Scott, Democrat of Virginia and the measure’s chief sponsor.

Still, Democratic moderates — especially those who represent districts carried by President Trump — were nervous about the measure, and it took champions of the bill months to bring them around. In the end, the sponsors tacked on two provisions: one authorizing a study of the measure’s effects after it has been in place for two years, and another extending the deadline for a $15 minimum wage from 2024 to 2025.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the liberal Democrat from New York and a strong ally of the Fight for $15 movement, called the vote a “huge deal.” But she signaled the fight is not over.

“It’s not just about $15, it’s about $15 and a union,” she said. “Fifteen started 10 years ago, so what is that pegged to inflation today? That’s why what we fight for is a living wage. So I think that this vote is an important milestone.”

The federal government sets the floor for the minimum wage; states can enact higher minimums. Raising the minimum wage to $15 by 2025 will pull 1.3 million American out of poverty and could result in wage increases for up to 27 million workers, according to a recent Congressional Budget Office analysis.

But it would leave 1.3 million people, or 0.8 percent of the work force, out of a job, the same study concluded. While the legislation would boost incomes at the bottom, it would cost richer households and would slightly reduce gross domestic product.

Republicans focused on the C.B.O.’s job loss figure, as well as regional disparities in the cost of living. They invoked their favorite epithet for the Democrats of the new House — “socialist” — in arguing against the measure.

“Let’s leave freedom in the hands of the people, in the hands of the states — that’s what this country is all about,” said Representative Virginia Foxx, Republican of North Carolina, who managed the bill for Republicans on the House floor. “In socialist regimes, all decision are made by a small group of people at a central government. That is not the American way.”

Economists have increasingly accepted that some level of minimum wage increase can work — coming at a minimal cost to jobs — in some jurisdictions, said David Neumark, an economist at the University of California at Irvine who has studied minimum wages extensively. But a one-size-fits-all policy that more than doubles some businesses’ wage bills could hit employers in lower-pay areas hard, he said.

“It has had what I would say was a remarkable and unexpected political success,” Mr. Neumark said of the $15 minimum. “Does it make sense? Call me skeptical.”

But some advocates of a higher minimum wage want to push pay up even farther. Among them is Heidi Shierholz, an economist at the union-funded Economic Policy Institute, who said even $15 will not be adequate if workers have to wait until 2021, when a Democrat could again occupy the White House.

“The Fight for $15 was launched in 2012, and every year that passes, the purchasing power of $15 goes down,” she said.

Ms. Pelosi had promised a vote on the wage bill soon after Democrats took power in January, but party leaders soon found that was going to be impossible; too many moderates were uneasy with it. Along with Representative Robert C. Scott, Democrat of Virginia and the bill’s chief sponsor, Ms. Pelosi deputized Representative Stephanie Murphy, who represents a swing district in Florida, to build support for the bill.

“We’re unifying behind the idea that we need to help hardworking families make ends meet,” said Ms. Murphy, whose district includes many workers employed at Disney World, which recently agreed to raise its minimum wage to $15 by 2021.

To fast-food workers like Terrence Wise, 40, who lives in Kansas City, Mo., and makes $12 an hour working full-time at McDonald’s, the vote shows the power of grass-roots activism.

“We’re a powerful voting bloc,” said Mr. Wise, a longtime leader of the Fight for $15 movement, “and we will take that power to the ballot box.”

The push for a $15 minimum wage began in New York City, when a group called New York Communities for Change started visiting fast-food restaurants and talking to workers about their grievances.

“Fast food workers always believed that there would be a national shift to $15,” said Mary Kay Henry, head of Service Employees International Union, which has helped provide institutional support to Fight for $15 from the outset. She recalled marching alongside them in 2012 and thinking that the goal was ambitious — because Democrats were talking about $9 and $10.10 minimums at the time. “I remember thinking, ‘Holy moly. How long is this going to take us?’”

Seven states have now passed legislation to gradually raise wages to $15, and cities including San Francisco and New York City already pay that much. In total, 29 states now have floors higher than the federal minimum, according to the Labor Department.

Companies have even joined in, with corporations including Amazon and Target raising their base wages to $15. By the 2016 midterm elections, $15 was resonating at a national level, making it into the Democratic Party platform. Support for striking workers has become common among Democratic presidential hopefuls including South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey.

“The successes in the municipalities and states are key,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office who has advised Republican presidential candidates and is now president of the American Action Forum. “All of that laid down the predicate that people wanted this.”

But Mr. Holtz-Eakin said raising the national minimum wage would be a mistake, in part because labor conditions vary dramatically around the country. He said it is unlikely that the minimum wage will pass at $15 by 2025, even if a Democrat wins the White House in 2020.

“Politically, it’s a popular one, there’s no question,” he said. “I think it gets bargained down in the process.”

0 notes