#(it's ethnologue)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The most annoying thing Christian missionaries have done is describe language in-depth because now we owe one of the largest databases of language to people who I don't think are very good

#they're not like normal christians either they're evangelicals#(it's ethnologue)#it is interesting speaking multiple languages bc the English wikipedia article describes it as neutral and not actually religiously#affiliated#but the Swedish article says its neutrality as a scientific creation is debated#especially regarding languages connected to the bible or abrahamic religions#note I say annoying because they have definitely done much worse things#but I wouldn't describe those things as annoying

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

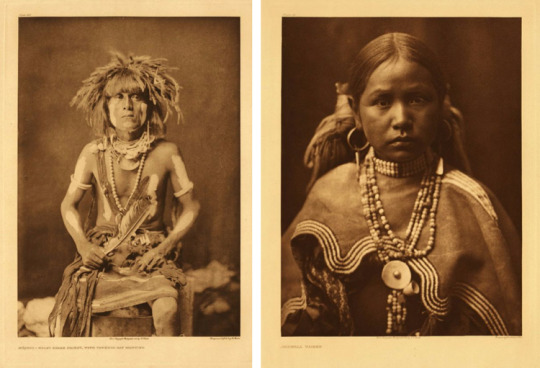

40 portraits d'amérindiens du début du 20ème siècle par Edward S. Curtis

Nouvel article publié sur https://www.2tout2rien.fr/40-portraits-damerindiens-du-debut-du-20eme-siecle-par-edward-s-curtis/

40 portraits d'amérindiens du début du 20ème siècle par Edward S. Curtis

#20ème siècle#amérindien#Amérique#années 1900#Edward S.Curtis#ethnologue#histoire#indien#photographe#portrait#vintage#imxok#people

0 notes

Text

This list of the 11 most spoken first languages is from the 2024 publication of Ethnologue (via Wikipedia).

–

We ask your questions so you don’t have to! Submit your questions to have them posted anonymously as polls.

#polls#incognito polls#anonymous#tumblr polls#tumblr users#questions#polls about language#submitted june 24#polls about the world#language#first language#languages#linguistics

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

language learning websites list

Endonym Map: World Map of Country Names in Their Local Languages

Dropbox - linguistics - Simplify your life

Dropbox - language textbooks - Simplify your life

Ethnologue | Languages of the world

Etymonline - Online Etymology Dictionary

spanish

Spanish (Mexico) Vocabulary

spanish_grammar.pdf

Spanish 1/The Basics - Wikiversity

portuguese

Portuguese Language/Introduction - Wikiversity

Portuguese/Contents - Wikibooks, open books for an open world

asl

Learn How to Sign - YouTube

American Sign Language 1 - Fall 2023

other languages

Native American Language Net: Preserving and promoting First Nations/American Indian languages

Arabic from the Beginning - YouTube

Urdu/Hindi language and literature: resources for study

Learn Urdu online, Urdu language & alphabets learning | Aamozish

translation

DeepL Translate: The world's most accurate translator

World Free Translators Dictionaries Encyclopedias

ipa/pronunciation

Interactive IPA

IPA i-charts (2023)

IPA Chart

Forvo: the pronunciation dictionary. All the words in the world pronounced by native speakers

writing systems

ScriptSource - Writing systems, computers and people

World Writing Systems

toki pona

Toki Pona

sona pona

CEFR Analysis for toki pona

mun! - Learn Toki Pona!

lipu Linku

lipu pi jan Ne

lipu sona pona

sitelen sitelen

Toki Pona Dictionary

lipu lili pona

Wikipesija

lipu pi ijo pi toki pona

printable dictionary

sike pona

nasin toki pona—a good way to speak

lipu nimi

semantic spaces dictionary

toki pona | lipu pi soweli nata

Toki Pona

telo misikeke

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is Ethnologue's 2024 list of languages with more than 50 million speakers:

Presumably, among my followers or people who will see this post are people who speak some of these languages, or have some familiarity with them. To those people: what media (books, films, etc.) in your language do you like the best? What media do you most wish you could share with non-speakers of the language? What works (both classic and popular) are the most famous, well-known, or esteemed in your language?

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Badeshi: Only three people speak this 'extinct' language

By Zafar Syed, February 2018

Would you like to learn a few words of a language only three people in the world speak?

Badeshi used to be spoken widely in a remote snow-clad valley, deep in the mountains of northern Pakistan.

But it is now considered extinct.

Ethnologue, which lists all of the world's languages, says it has had no known speakers for three or more generations.

But in the Bishigram Valley, we found three old men who can still speak in Badeshi (you can hear them in the video at the link).

"A generation ago, Badeshi was spoken in the entire village", says Rahim Gul. He doesn't know how old he is, but looks over 70.

"But then we brought women from other villages [for marriage] who spoke Torwali language. Their children spoke in their mother tongue, so our language started dying out."

Torwali is the dominant language in the area, which is itself under pressure from Pashto, but has pushed Badeshi to the brink in this valley.

"Now our children and their children speak Torwali," said Said Gul, Rahim Gul's first cousin. "So who should we speak our own language with?"

Said Gul also doesn't know his own age. When he said he was 40, somebody corrected him. "It's more like 80!" Said Gul quickly shot back, "No, may be 50, but not 80!"

There are no job opportunities in the area, so these men have spent a lot of time in touristy Swat District, where they have picked up the Pashto language, and that is mainly how they communicate.

Because of a lack of opportunities to use Badeshi, over the decades even these three men have started forgetting the language.

While they were talking in Badeshi, Rahim Gul and Said Gul regularly forgot a word or two, and could only remember after prodding from the others.

Rahim Gul has a son, who has five children of his own, but all of them speak Torwali.

"My mother was a Torwali speaker, so my parents didn't speak any Badeshi in the house. I didn't get a chance to pick it up in childhood. I know a few words, but don't know the language. All my children speak Torwali.

"I do regret it, but now that I'm 32 there is no chance I can learn Badeshi. I'm very sad at the prospect that this language will die out with my father."

Sagar Zaman is a linguist affiliated with the Forum for Language Initiative, a non-governmental organisation dedicated to the promotion and preservation of endangered languages of Pakistan.

"I travelled to this valley three times, but the inhabitants were reluctant to speak this language in front of me," he says.

"Other linguists and I were able to collect a hundred or so words which suggested that this language belongs to Indo-Aryan sub family of languages."

Zaman Sagar says Torwali and Pashto speakers look down upon Badeshi, so there is a stigma attached to speaking it.

Perhaps it's too late to save Badeshi, but at the very least, you can learn a few words to keep the memory of the language alive:

Meen naao Rahim Gul thi - My name is Rahim Gul

Meen Badeshi jibe aasa - I speak Badeshi

Theen haal khale thi? - How do you do?

May grot khekti - I have eaten

Ishu kaale heem kam ikthi - There is not much snowfall this year

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

inspired by thinking about projects like ethnologue that basically just exist to give missionaries more access to indigenous populations. any positive coming from the studying of minority languages is pretty quickly being undone by the fact that study is being used to print bibles for missionaries

countries should be allowed to confiscate missionaries passports and deport them tbh

sorry but you don't get access to people to colonise, go home

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

What's the average language like?

This will be a giant of a post, because this is a subject that I really like. So much of what we think about language just isn't true when you look at the majority of them and I'm not even going into how the languages themselves are constructed, only the people speaking them, if that makes sense. It will make sense in a moment, I promise

First, let's discuss assumptions. When you think of the abstract idea of a language, what do you imagine?

How many speakers?

Where is it spoken geographically?

Do speakers of the language only speak that language or do they speak at least one other language? How many more languages?

Is the language tied to a state/country?

Is the language thriving or endangered?

In what domains is the language used? (home, school, higher education, administration and politics, in the workplace, in popular media...)

Is the language well documented and supported? Are there resources like dictionaries to look up words in, does google translate work for it, does Word/google docs work etc?

Is the language spoken or signed?

Is the language written down? Is it written down in a standardised way?

Do you see where I'm going with this? My perspective on what a language is has completely shifted after studying some linguistics, and this only covers language usage and spread, not how words and grammar work in different languages. Anyways, let's talk facts. (if no other sources are given the source is my uni lectures)

How many speakers does the average language have?

The median language has 7 600 native speakers.

7 600 people is the median number of speakers. Half the world's languages have more, half have less.

Most languages in this tournament have millions of speakers. But maybe that's relatively common? After all, half of the world's languages have more than 7 600 speakers. No.

94% of all languages have less than a million speakers.

Just so you know, big languages are far from the norm. There are 6700-6800 living languages in the world (according to ethnologue and glottolog, the two big language databases. I've taken the numbers for languages having a non-zero number of speakers and not being classed as extinct respectively. Both list more languages).

6% of 6700-6800 languages would be around 400 languages with more than a million speakers. Still a lot, but only a (loud) minority. It's enough to skew the average number of speakers per language upwards though. Counting 8 billion people and 6800 languages, that's almost 1.2 million people per language on average. The minority is Very loud.

Where are most languages spoken?

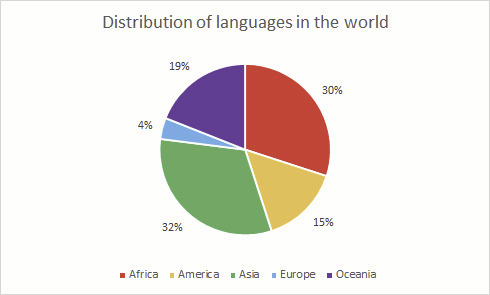

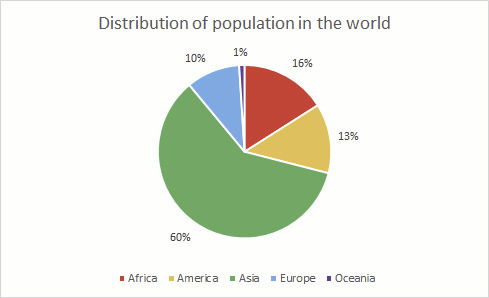

First of all, I'll present you with these graphs (data stolen from my professor's powerpoint) which I first showed in this post:

49% of all languages are spoken in Africa and Oceania, a disproportionately large amount compared to their population. On the other hand, Europe and Asia have disproportionally few languages, though Asia still has the largest amount of languages. Curious, considering Europe is often thought of as a place with many languages.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a very linguistically interesting place, but we need to talk about New Guinea. One island with 6.4 million people. Somehow over 800 languages. If you count the surrounding islands that's 7.1 million people and 1050 languages. Keep in mind that there are 6700-6800 languages in the world, so those 1050 make up more than a seventh of all languages. The average New Guinean language has less than 3000 speakers. Some are larger, but still less than 250 000 speakers. Remember, this is a seventh of all languages. It's a lot more common than the millions of speakers situation!

So yeah, many languages both in and outside New Guinea are spoken by few people in one or a few villages. Which is to say a small territory. But 7600 speakers spread over a big territory will have a hard time keeping their contact and language alive, so it's not surprising.

Moving on, lets talk about...

Bilingualism! Or multilingualism!

Is it common to speak two or more languages? Yes, it is. This is the situation in most of the world and has been the case historically. Fun fact: monolingual areas are uncommon historically and states which have become monolingual became so relatively recently.

One common thing is to learn a lingua franca in addition to your native language, a language that most people in the area know at least some of so you can use it to communicate with people speaking other languages than you.

As an example, I'm writing this in English which isn't my native language and some of you reading this won't have English as your native language either. Other examples are Swahili in large parts of eastern Africa and Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea (the autonomous state, not the entire island).

Speakers of minority languages often have to learn the majority language in the country too. It's difficult to live somewhere where most daily life takes place in one language without speaking at least some of it. This is the case for native people in colonised countries, immigrants and smaller ethnic groups just to mention a few situations. All countries don't have majority languages, but some are larger, more influential and used for things like administration, business and higher education. It's common for schooling to transition from local languages to a larger language or lingua franca in countries with many languages.

Another approach than the lingua franca is learning the language of villages or towns surrounding you, which is very common in New Guinea and certainly other parts of the world too. It's not unusual to know multiple languages, in some places in sub-saharan Africa people speak five or six languages on a village level. Monolingualism is a weird outlier.

Speaking of monolingualism, let's move on to...

Languages and countries

This is a big talking point, mostly because it affected my view of language before I started thinking about it. First of all, I'm going to talk about the nation state and how it impacts languages within it and the way people view language (mostly because it's a source of misconceptions which fall apart as soon as you start to think about them, but if you don't the misconceptions will stay). Then I'll move on to countries with lots of languages and what happens there instead.

So, the nation state

The idea is that the people of a nation state share a common culture, history, values and other such things, the most important here being language. We can all agree that this type of nationalism has done lots of harm to various minorities and migrants all over the world, but it's still an idea that has had and still has a big impact on especially the western world. The section on nation states will focus on the West, because that's the area I know enough about to feel comfortable writing about in this regard.

How do you see this in common conceptions of language? It's in statements and thoughts like this: In France people speak French (but what about Breton? Basque? Corsican? Various Arabics? Some of the other 15 indigenous and 18 non-indigenous languages established in France? What about people speaking French outside of France?), in the US people speak English (but what about the 197 living indigenous languages? Or the 34 established non-indigenous languages? And the many extinct indigenous languages forcibly killed by the promotion of English?).

In X country people speak X, except for the people who don't, but let's ignore them and pretend everyone speaks X. Which most might actually do if it's the single national language that's used everywhere, it's common to learn a second language after all.

This is of course a simplified (and eurocentric) picture, as many countries either have multiple national languages or recognise at least some minority languages and give them legal protection and rights to access certain services in their languages (like government agency information). Bi-/multilingual signage is common and getting more common, either on a regional or a national level. Maybe because we're finally getting ready to move on from one language, one people, one state and give indigenous languages the minimum of availability they need to survive.

I wrote a long section about how nation states affect language, but I realised that veered way off topic and should be its own post. The short version is that a language might become more standardised simply by being tied to a country and more mobility among the population leading to less prominent dialects. There's also been (and still is) lots of opression and attempts to wipe out minority (often indigenous) languages in the name of national unity. Lots of atrocities have been comitted. Sometimes the same processes of language loss happen without force, just by economic pressure and misconceptions about bilingualism.

What does this have to do with the average language?

I simply want to challenge two assumptions:

That all languages are these big national languages tied to a country

That it's common that only one language is spoken within a country. If you look closer there will be smaller languages, often indigenous and often endangered. There are also countries in the West where multiple languages hold equal or similar status (just look at Switzerland and its four official languages)

Starting with the second point, let's take a look at how Europe is weird about language again

Majority languges aren't universal

I'm going to present you with a list of the 10 countries with the most living languages, not counting immigrant languages (list taken from wikipedia, which has Ethnologue as the source):

Papua New Guinea, 840 languages

Indonesia, 707 languages

Nigeria, 517 languages

India, 447 languages

China, 302 languages

Mexico, 287 languages

Cameroon, 274 languages

Australia, 226 languages

United states, 219 languages

Brazil, 217 languages

DR Congo, 212 languages

Philippines, 183 languages

Malaysia, 133 languages

Chad, 130 languages

Tanzania, 125 languages

This further challenges the idea of one country one language. Usually there's a lingua franca, but it's not always a native language and it's not always the case that most are monolingual in it (like the US or Australia, both of which have non-indigenous languages as widespread lingua francas). Europe is the outlier here. People might use multiple languages in their day to day lives, which are spoken by a varying number of people.

In some cases the indigenous or smaller local languages are extremely disadvantaged compared to one official language (think the US, Australia and China), while in other places like Nigeria, several larger languages are widely used in their respective areas alongside local languages, with English as the official language even though it's spoken by few people.

It's actually pretty common in decolonised countries to use the colonial language as an official language to avoid favoring one ethnic group and their language over others. Others simply don't have an official language, while South Africa's strategy is having 12 official languages (there are 20 living indigenous languages and 11 non-indigenous languages in total, and one of the official ones is English, so not all languages are official with this strategy either). Indonesia handled decolonisation by picking a smaller language (a dialect of Malay spoken by around 10% at the time, avoiding favouring the Javanese aka the dominating ethnic group by picking their language), modifying it, and started using it as the new national language Indonesian. It's doing very well, but at the cost of many smaller languages.

Going back to the list, it's also interesting to compare the mean speaker number (if every language in a country was spoken by the same amount of people) and the median speaker number (half have more speakers, half have less). The median is always lower than the mean, often by a lot. This means that the languages in a country don't have similar speaker numbers, so one or a few languages with lots of speakers drive the average upwards while the majority of languages are small. Just like for the entire world.

The US and Australia stand out with 12 and 10 median speakers, respectively. About 110 languages in the US have 12 or fewer native speakers. The corresponding number for Australia is 113 languages with 10 or fewer speakers. There are some stable languages with few speakers documented, but they have/had between 40 and 60 speakers, so those numbers point towards a lot of indigenous languages dying very soon unless revitalisation efforts succeed quickly. This brings us to the topic of...

Endangered languages

This is an interesting tool called glottoscope made by Glottolog which you can play around with and view data on endangered languages and description status (which is the next heading).

I'll pull out some numbers for you:

Remember those 6700 languages in Glottolog? That's living languages. How many extinct languages are listed?

936 extinct languages. That's ~12,5% of the languages we know of. (Glottolog doesn't include reconstructed languages like Proto-Indo-European, only languages where we either have enough remaining texts to conclude it was a separate language or reliable account(s) that conclude the same. We can only assume that there are thousands of undocumented languages hiding in history that we'll never know of)

How many more are on the way to become extinct?

Well, only 36% (2800 languages) aren't threatened, which means that the other 64% are either extinct or facing different levels of threat

What makes a language threatened? The short answer is people not speaking the language, especially when it's not passed down to younger generations. The long answer of why that happens comes later.

306 languages are listed as nearly extinct and 412 more as moribound. That means that only the grandparent generation and older speak it and the chain of transmission to younger generations has broken. These two categories include 9,26% of all known languages.

The rest of all languages either fall into the threatened or shifting category. The threatened category means that the language is used by all generations but is losing speakers. The shifting category refers to languages where the parental generation speaks the language but their children don't. In both of these cases it's easier to revive the language, since parents can speak to the children at home instead of having to rely on external structures (for example classes in the heritage language taught like foreign language classes in schools).

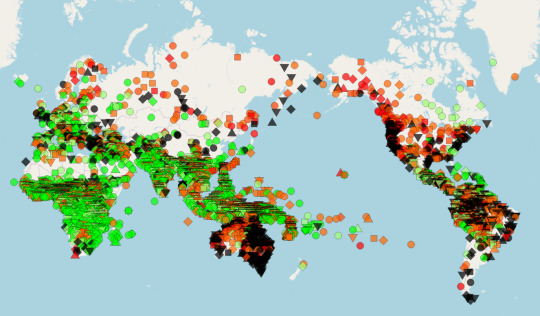

Where are languages threatened?

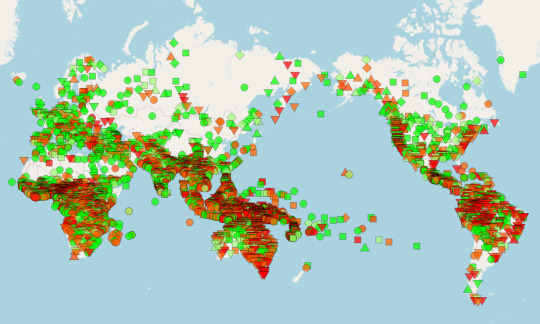

This map is also from glottoscope and can be found here. I recommend playing around with it, you can zoom in and hover over every dot to see which language it represents. The colours signify threat level: green for not threatened, light green for threatened, orange for shifting, red for moribound and nearly extinct, and black for extinct. I'll come back to the shapes later.

As you can see, language death is more common in certain areas, like Australia, Siberia, North America and the Amazon, but it's still spread over the entire world.

Why are languages going extinct?

There are two important dimensions to the vigorousness of a language: The first is the number of speakers who claim the language as their own and speak it with each other. No speakers means no language. If all speakers move to different places or assimilate by shifting to a dominant language in the area (sometimes for work opportunities or for their childrens' future work opportunities. Sometimes because of which language(s) schools are taught in or disinterest from the children in the language and culture. Sometimes migration of an ethnic group for various reasons leads to language shifts. There are many complex reasons to why the link of transmission can break)

The other dimension, which ties into the first one, is the number of situations in which a language is used. There are many domains a language can be used in, like at home, in school, in the workplace, in politics and administration, in higher education, for international communication, in religious activities, in popular media like movies and music etc. When a language is no longer or never used in a particular domain, it might lose the associated vocabulary. When it becomes confined to a singular domain like the home, the usage goes down. The home is usually the last place an endangered language is spoken.

Usage in a domain is a reason to speak or hear the language. It's a reason to keep it alive. People also forget or get worse at languages they don't use. That's why a common revitalisation tactic is producing movies, radio programmes, news reporting, books and other media in a dying language. It gives people both reason and opportunity to use their language skills. Which language is used in schools is also important, as it keeps basic vocabulary for sciences and explaining the world alive. Another revitalisation tactic is making up new words to talk about modern concepts, some examples are the Kaqchikel word rub'eyna'oj from this tournament or creating advanced math vocabulary in Māori.

What does endangered languages have to do with the average language?

Trying to get this post back on track, these are some key points:

64% of all documented languages are either extinct or facing some level of threat. That's the majority of all language

Even excluding the extinct languages, the majority of languages are threatened or worse

This means that the average language is facing a loss of speakers, some more disastrous than others. Being a minority language in an increasingly globalized world is dangerous

Describing a language

Are you able to look up words from your native language in a thesaurus or a dictionary? What about figuring out how a certain piece of grammar works if you're unsure? Maybe you don't need that for your native language, but what about a second language you're learning?

If your native language is English, there are lots of resources, like online and book dictionaries/thesauruses or an extensive grammar (a book about how English grammar works). There's also a plethora of websites and courses to learn English, and large collections of written text or transcribed speech. If a linguist wants to know something about the English language there's an abundance of material. If someone wants to learn English it's easy and courses are offered in most parts of the world.

For other languages, the only published thing might be a list of 20 words and their translation into English or another lingua franca.

Let's take a look at the same map as earlier, but toggled to show documentation status in colour and endangerment status with shapes:

Here, the green signifies a long grammar and the light green a grammar. Both are extensive descriptions of the grammar in a language, but they differ in length. A long grammar has to contain over 300 pages and a grammar over 150. Orange is another type of grammar, namely a grammar sketch. Those are brief overviews of the main grammatical features or features that may be of interest for linguists, typically between 20 and 50 pages. The purpose isn't to be a complete grammar, only a starting point.

The red dots can signify a lot of things, but what they have in common is that there's no extensive description of the grammar. In those cases, the best description of the language might be a list of which sounds it contains, a paper about a specific feature, a collection of texts or recordings, a dictionary, a wordlist (much shorter than dictionaries) or just a mention that it exists.

Why are grammars and descriptions even important?

The better described a language is, the easier it is to learn it and study it. For a community facing language loss, it might be helpful to have a pedagogical grammar or a dictionary to help teach the language to new generation. If the language becomes extinct people might still be able to learn and revive it from the documentation (like current efforts with Manx). It also makes sure unique words or grammatical features as well as knowledge encoded in the language isn't lost even if the language is. It's a way of preserving language, both for research and later learning.

What's an average amount of descripion then?

36,2% of all documented languages have either a grammar or a long grammar. That's pretty good actually

38,2% of all documented languages would be marked by a red dot on this map, meaning that more languages than that don't have any kind of grammar at all, maybe only as little as a short list of words

The remaining 25,6% have a grammar sketch

So as you see, the well documented languages are in minority. On the brighter side, linguists are working hard at describing languages and if they keep going at the same rate as they have since the 1950s, they'll reach the maximum level of description by 2084. Progress!

Tying into both description of languages and domains where language is used...

What about technology and language?

There are many digital tools for language. Translation services, spelling and grammar checks in word processors, unicode characters for different scripts and more. I'm going to focus on the first two:

Did you know that there are only 133 languages on google translate? 103 more are in the process of being added, but that's still a tiny percentage of all languages. As in 2% right now and 3,5% once these other languages are added going with the 6700 language estimation.

Of course, this is for the most part a limination with translation technology. You need translated texts containing millions of words to train the algorithms on and the majority of languages don't have that much written text, let alone translated into English. The low number still surprised me.

There are 106 official language packs for Windows 10 and I counted 260 writing standards you can use for spelling checks in Word. Most were separate languages, but lots were different ways to write the same language, like US or British English. That's a vanishingly small amount. But then again:

Do all languages have a written standard?

No. That much is clear. But how many do? I'll just quote Ethnologue on this:

"The exact number of unwritten languages is hard to determine. Ethnologue (25th edition) has data to indicate that of the currently listed 7,168 living languages, 4,178 have a developed writing system. We don't always know, however, if the existing writing systems are widely used. That is, while an alphabet may exist there may not be very many people who are literate and actually using the alphabet. The remaining 2,990 are likely unwritten."

(note that Ethnologue classes 334 languages without speakers as living, since their definition of living language is having a function for a contemporary language community. I think that's a bad definition and that means it differs from figures earlier in the post)

Spoken vs signed

My last point about average languages is about signed languages, because they're just as much of a language as spoken ones. One common misconception is that signed languages reflect or mimic the spoken language in the area, but they don't. Grammar works differently and some similarities in metaphor might be the only thing the signed language has in common with spoken language in the area.

Another common misconception is that there's only one sign language and that all signers understand each other. That's false, signed languages are just as different from each other as spoken languages, except for some tendencies regarding similarity between certain signs which often mimic an action (signs for eating are similar in many unrelated sign languages for example).

Glottolog lists 141 Deaf sign languages and 76 Rural sign languages, which are the two types of signed language that become entire languages. The difference is in reach.

Rural signs originate in villages with a critical amount of deaf people (around 6) that make up a fully fledged language with complete grammar to communicate. Often large parts of the village learn tha language as well. There are probably more than 76, that's just the ones the linguist community knows of.

What's called Deaf sign languages became a thing in the 1750s when a French guy named Charles-Michel de l'Épóe systematised and built onto a rural sign from Paris to create a national sign language which was then taught in deaf schools for all deaf children in France. Other countries took after the deaf school model and now there's 141 deaf sign languages, each connected to a different country. Much easier to count than spoken languages.

Many were made from scratch (probably building on some rural sign), but some countries recruited teachers from other countries that already had a natinonal sign language and learnt that instead. Of course they changed over time and with influence from children's local signs or home signs (rudimentary signs to communicate with hearing family, not complete languages), so now there's sign language families! The largest one unsurprisingly comes from LSF (Langue des Signes Française, the French one) and has 63 members, among them ASL.

What does this have to do with average languages? Well, languages don't have to be spoken, they can be signed instead. Even if they make up a small share of languages, we shouldn't forget them.

Now for some final words

Thank you for reading this far! I hope you found this interesting and have learned something new! Languages are exciting and this doesn't even go inte the nitty gritty of how different languages can be in their grammar, sounds and vocabulary. Lots of this seem self evident if you think about it, but I remember how someone pointing out facts like this truly shifted my perspective on what the language situation in the world truly looks like. The average language is a lot smaller and diffrerent from the common idea of a language I had before.

Please reblog this post if you liked it. I spent lots of time writing it because I'm passionate about this subject, but I'd love if it spread past my followers

#linguistics fun fact time!#anyways can't believe this is finally done#i was going to make a series with informative posts between each round#and look what happened#i spent all my time writing this instead#hope you enjoyed!#and check out the linguistics fun facts tag#there are some more posts like this#linguistics

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think linguistics has a huge methodological problem, in that while there exist some formalised methodologies for conducting investigations, it's clear that you don't have to pursue any of them to actually get ahead academically because linguists aren't actually as scientifically rigorous as they would like to think.

This has knock-on effects for more general experimental design, because it is extremely common to find studies which purport to prove/disprove some hypothesis, but when you actually look at the methodology they use you find that it doesn't actually provide evidence for the point they're attempting to make.

Of course the most common place to find this kind of stuff is in the Generativist literature, which is awash with claims the phenomena they describe is only explainable through the assumption of Universal Grammar/a Language Organ/whatever, when in fact non-innatist models work just as well. But this isn't the only part of the field that is susceptible to this.

So for instance there was a paper put out in Science recently that claims to have found evidence to counteract the idea that social structure can have an impact on the structure of the language (most notably explicated by Peter Trudgill in his 2011 book Sociolinguistic Typology, give it a read if you can find it). They take demographic data from Ethnologue and compares this with a couple of metrics which supposedly quantify linguistic complexity.

Leaving aside the (sometimes glaring) issues with the way the metrics are defined (they perhaps could have done with reading Dahl 2004 The Growth and Maintenance of Linguistic Complexity), we can already spot a major problem with using these correlations to make claims regarding the Sociolinguistic Typology hypothesis: the phenomena in question are explicitly diachronic in nature, but the data being used to assess them is solely synchronic.

What do I mean by this? It's been suggested that English morphology is less complex relative to e.g. German because of contact with the large numbers of Old Norse speakers that settled in the Danelaw. The trouble is, of course, that all those Norse speakers later shifted to English, so this large community of L2 learners won't show up in the data, despite the effects still being apparent after over 1000 years. Similar points can be made about most of the languages where these kinds of effects have been proposed: it was precisely the process of these languages spreading rapidly and acquiring a large speakerbase in a disorganised fashion that cause these changes to occur. Indeed, the authors specifically note that education and official language status are factors that would mitigate against the failures of L2 transmission that are claimed to cause these simplification effects, but don't then seem to acknowledge that this is a major issue for extrapolating the correlations anywhere further back than the 19th Century.

I think there are several things going on here which have led to this kind of thing being possible. Firstly, linguistics has always had an uneasy continuing relationship with the rest of the humanities and parts of the sciences (particularly neurobiology and acoustics), because it touches on so many of them at once. Secondly, and relatedly, we've had a fairly significant period where the core theoretical concerns of linguistics were essentially driven by a philosopher (Chomsky), which created a model of research that explicitly rejected empirical work and argued for much of its base assumptions (such as 'Poverty of the Stimulus') almost entirely by thought experiment. Empirically minded subfields continued to exist (Trudgill for instance made his career as a sociolinguist), but empiricism has been slow to make a return to theoretical linguistics. As a result, it seems to me that, at least in typology, people are still getting to grips with the idea of formulating hypotheses and actually working out tests that actually assess those hypotheses. Thirdly, because again of Chomsky, linguistics has had a strongly mathematical character in terms of its conception of language, and this again still lingers in the design of these kinds of studies. Everything has to be quantified in such a way that a simple computer model can work with it, but the trouble is there's frequently little room for the nuances of individual languages (e.g. Irish and Welsh are both counted on WALS as having the same value for inflection on adpositions, but actually a detailed study of the two languages reveals their systems work really quite differently, as I'll perhaps post on another time) which can therefore have knock-on effects for the analysis of any correlations thus derived.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every day praising an indigenous character Day 43-

Sucy Manbavaran from Little Witch Academia

Sucy Manbavaran (スーシィ・マンババラン Sūshī Manbabaran?) is one of the main protagonists of Little Witch Academia. She is a young witch from Southeast Asia.

Her first name, "Sucy", can mean "holy" in Malay and Indonesian, and may also be derived from "Susi" in Filipino, which means "key"; while her surname, "Manbavaran", is apparently derived from "Mambabarang" in Cebuano, which means "warlock/witch" and "black sorcerer/sorceress".

The Cebuano people are the indigenous people of the Philippines, Southeast Asia.

The Cebuano people (Cebuano: Mga Sugbuanon) are the largest subgroup of the larger ethnolinguistic group Visayans, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group in the country. They originated in the province of Cebu in the region of Central Visayas, but then later spread out to other places in the Philippines, such as Siquijor, Bohol, Negros Oriental, southwestern Leyte, western Samar, Masbate, and large parts of Mindanao.

Visayans or Bisayans are the indigenous people of the Visayan Islands. They speak many languages, of which the largest in terms of number of speakers today is Cebuano. According to Ethnologue there are 25 Bisayan language, although at least one (Tausug) is spoken by a group considered to be outside the Visayan culture area.

Visayans (Visayan: mga Bisaya; local pronunciation: [bisaˈjaʔ]) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic family group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao.

#Every day praising an indigenous character#sucy manbavaran#sucy little witch academia#little witch academia#lwa#Native#Indigenous#Cebuano#Filipino

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kawalan ng mother tongue sa paaralan, pagbura ng ating kultura, at pagbaba ng kalidad ng edukasyon

Likha ni: Amihan Danao ng UPIS Media Center 2025

Ang Pilipinas, sa kasalukuyan, ay may 175 na living languages (Ethnologue, 2024). Sa iba’t ibang parte ng bansa, mayroon tayong sari-sariling inang wika o mother tongue at ang mga wikang ito ay nagpapakita kung gaano kayaman ang ating kultura rito sa Pilipinas. Ang mother tongue ay mahalaga para mas makilala ng mga bata ang kanilang identidad bilang isang Pilipino.

Pero noong Oktubre 12, 2024, nag-lapse sa isang batas ang RA 12027 o ang batas kung saan ipapahinto ang mother tongue bilang pangunahing medium of instruction para sa mga estudyante na nasa Kinder hanggang Grado 3. Nagiging batas ang isang panukalang batas kapag hindi nag-veto ang pangulo sa loob ng 30 araw matapos itong maipasa sa kanya. Sa ilalim ng RA 12027, ang pangunahing midyum ng pagtuturo ay ibabalik sa Filipino at Ingles habang ang mga rehiyonal na wika ay magiging suplementaryo na lamang para sa mga estudyante.

Ayon kay House Deputy Minority Leader at ACT Teachers Rep. France Castro, ang pagtanggal ng mother tongue bilang medium of instruction ay isang hakbang paatras sa pagbibigay ng mataas na kalidad ng edukasyon para sa mga estudyante. Sinabi rin niya na ang pag-abandona sa mother tongue ay pagtalikod sa iba’t ibang wika ng bansa at ang ambag nito sa iba’t ibang kultura mayroon tayo.

Kaya itatanong natin, ano ba ang halaga ng magkakaroon ng Mother Tongue based education sa loob ng silid-aralan at sa ating identidad bilang mga Pilipino? Ito ba ay usapang kultura lamang o baka usapin rin tungkol sa ating sistema ng edukasyon?

Ano ba ang Mother Tongue o ang MTB-MLE?

Unang naitakda ang MTB-MLE o ang Mother Tongue – Based Multilingual Education sa DepEd Order No. 74, series of 2009 na nagmamandato sa paggamit ng Mother Tongue (MT) bilang pangunahing midyum ng pagtuturo sa unang apat na taon sa elementarya habang ang mga estudyante ay natututo ng Filipino at Ingles bilang hiwalay ng mga subject. Pagkalipas ng apat na taon, ipinaloob ito sa implementasyon ng K-12 Basic Education Program na nasa ilalim ng Republic Act 10523 o ang Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013.

Ayon sa curriculum framework ng MTB-MLE, ito ay isang pormal o di-pormal na edukasyon kung saan ginagamit ang mother tongue ng estudyante at mga ibang wika sa loob ng silid-aralan. Ang pangunahing layunin nito ay upang makalatag ng matibay na pundasyon sa mother tongue ng estudyante bago magdagdag ng mga karagdagang wika (Department of Education, 2016). Sa pamamagitan ng mother tongue sa loob ng paaralan, mas maiintindihan nila ang kanilang mga aralin dahil ito ang wika na pinakanaiintindihan nila.

Pinagbatayan nila sa pagbubuo ng kurikulum ang mga umiiral na mga pananaliksik na nagpapatunay na epektibo ang paggamit ng mother tongue o ang first language (L1) ng mga bata upang makatulong sa pag-develop nila ng ibang wika. Isa sa mga pinagbatayan nila na mananaliksik sa loob ng curriculum guide ng MTB-MLE ay si Jim Cummins, isang propesor sa Canada na kilala para sa kanyang Second Language Acquisition Theory. Ayon sa kanya, ang level of development ng mother tongue ng isang bata ay isang strong predictor para sa kanilang language development.

Ngunit, noong Agosto 10, 2023, inilunsad ng dating DepEd Secretary at kasalukuyang Bise Presidente na si Sara Duterte ang MATATAG curriculum, at isa sa mga naging malaking pagbabago rito ay ang pagtanggal ng Mother Tongue bilang isang subject.

Mga Kritisismo at Problema sa Mother Tongue

Isa sa mga naging pangunahing kritisismo sa MTB-MLE ay ang implementasyon nito. Nagdulot ito ng kalituhan sa mga guro, lalo sa mga taga-Luzon dahil tinatanong kung ano ba ang pagkakaiba ng Filipino at Mother Tongue bilang subject (Hernando-Malipot, 2023). At ayon sa isang pag-aaral ng Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) na pinamagatang “Starting Where the Children Are’: A Process Evaluation of the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Implementation,”, nagkaroon ng pagtutol sa paggamit ng MT bilang midyum ng pagtuturo dahil hindi naiparating nang maayos sa mga magulang ang silbi ng MTB-MLE at sa tingin nila ay hindi raw ito mahalaga para makakuha ng trabaho. Hindi rin na-assess nang maayos ang kakayahan ng mga guro upang ituro ang MT at hindi rin sila nabigyan ng sapat na training para maituro nila ito nang maayos. Nagkaroon lamang ng nationwide training para sa mga guro isang buwan bago i-implement ang programang K-12 noong 2012. (Monje, et al, 2021). Dagdag dito, sa pag-aaral na isinagawa ng Cardno Emerging Markets noong 2017, natuklasan nilang higit sa 200 na guro sa Bangsamoro Region na kasama sa reading program ng DepEd ay nakapuntos nang mas mababa sa 50% sa reading comprehension, kahit matapos makatanggap ng training, (Chi, 2024).

Mas lalong bumaba rin ang literacy rate ng bansa habang ipinapatupad ang bagong language policy hanggang sa punto na nagkaroon lamang ng aksyon galing sa DepEd sa pamamagitan ng DepEd Memorandum No. 173, series of 2019, (Hamon: Bawat Bata Bumabasa) na nagpapakitang malala na masyado ang problema. Ayon sa DepEd-Cordillera regional director na si Estela Cariño, mas natututo nang mabuti ang mga estudyante sa Ingles at Filipino bilang midyum ng pagtuturo kaysa sa kanilang mother tongue (INQUIRER, 2023).

Ang pangunahing rason kung bakit nagkaproblema ang pagpapatupad ng MTB-MLE sa mga paaralan ay ang kakulangan ng suporta ng gobyerno. Hindi nabigyan ng sapat na materyales ang mga guro at kinailangan pang igiit at ipaglaban ang pondo para sa mga aktibidad na kaugnay ng programang MTB-MLE. Nagkakaroon ng disparency sa ginagamit na wika sa mga instructional materials sa aktwal na Mother Tongue ng mga estudyante at mas nalilito sila rito kasi hindi tugma ang wika ng ginagamit sa loob ng klase sa wika na ginagamit ng nila. Sa halip na ang Department of Education ang magbibigay ng mga localized materials sa konteksto ng Mother Tongue ng mga estudyante, napupunta ang bigat ng trabaho sa mga guro, bagaman marami na silang ginagawa sa loob ng paaralan at mas mapapalayo pa sila sa mga estudyante nila (Hunahunan, 2019).

Halaga ng Mother Tongue

Bukod sa pagiging malaking tulong ang Mother Tongue sa pag-aaral sa ibang wika, ito rin ay nakakatulong sa language vitality o ang kalusugan at lakas ng mga wika natin at magkaugnay sa education inclusion (INQUIRER, 2023). Batay sa kasalukuyang datos ng Ethnologue, 55 sa mga wika ng Pilipinas ay endangered, at dahil tinanggal ang Mother Tongue sa curriculum ng mga paaralan, inaasahan na mas lalong bibilis ang paghina ng mga wika natin na maaaring magresulta ng pagkawala ng ating mayamang kultura.

Hindi limitado ang halaga ng Mother Tongue sa usapang kultura lamang, kundi pati rin sa kabuuang identidad ng isang lipunang Pilipino. Sa papel na pinamagatang “The Miseducation of the Filipino” na isinulat ni Prof. Renato Constantino, isang historyador, tinalakay niya na dahil nakikita natin na kailangan makipag-ugnayan sa isa’t isa gamit ang isang wikang banyaga, napapabayaan na natin ang ating sariling wika at nahihirapan na tayong gamitin ito. Sabi rin niya na ang wika ay isang tool sa thinking process. Sa pamamagitan ng wika, nakakapag-isip ang isang tao. At habang mas nakakapag-isip ang tao ay mas napapalakas niya ang paggamit ng wika. Pero pag ang wika ay naging harang sa pag-iisip, nahahadlangan ang proseso ng pag-iisip at ito ay nagkakaroon ng cultural stagnation. Hindi maayos ang pag-unlad sa kanilang kakayahan sa creative thinking, analytical thinking, at ang abstract thinking kasi mas nakatuon sa pagsasaulo o memorization ang bata gamit ang banyagang wika. Dahil sa mekanikal proseso ng pag-aaral, hindi nila napapalalim ang kanilang pag-uunawa sa pangkalahatang ideya (Constantino, 1982).

Sa isang pahayag ni Cebu Rep. Eduardo Gullas noong International Day of Education, sabi niya na kailangan palakasin ang Ingles bilang pangunahing midyum ng pagtuturo ng paaralan. Dagdag niya, ang rason ng pagiging mababa ng performance sa matematika at agham ay dahil sa mahinang kasanayan sa pagbasa at pag-unawa sa wikang Ingles (Corrales, 2021). Pero kung tutuusin, ang totoong rason kung bakit kulang ang kakayahan sa matematika at agham ay dahil hindi natin gamay ang sarili nating wika. Ang wikang banyaga, kagaya ng Ingles, ay dapat tinuturo lamang at mas madaling ituro kung kaya natin gamitin ang ating sariling wika.

Kaya kung sa simula pa lang, nahihirapan na tayo sa mga wika natin dahil hindi ito binibigyan ng halaga ng ating gobyerno, paano pa ba tayo sa internasyonal na lebel? Paano tayo makakapag-isip para sa ating bansa kung hindi naman tayo marunong makipag-ugnayan sa isa’t isa gamit ang wika natin bilang mga Pilipino?

Kaya pa ba natin ibalik ang Mother Tongue at pagbutihin ito?

Sa simpleng salita, oo. Pero ito ay isang mahabang proseso nangangailangan ng aksyon galing sa gobyerno, sa mga guro, sa mga magulang, at sa mga estudyante. Ang unang hakbang upang mas gumanda ng kalidad ng ating edukasyon sa pagbasa at sa pag-unawa ng mga salita ay hindi sa pagpapalakas ng wikang Ingles bilang pangunahing midyum ng pagtuturo. Ito ay nagsisimula sa mga wika natin sa Pilipinas.

Ang usapin ng wika sa loob ng silid-aralan ay nagbubukas pa ng mas malalim na isyu at ito ang usapin ng prioridad ng gobyerno sa edukasyon. Hindi lang ito tungkol sa pagpapahalaga sa ating mayaman na kultura at identidad bilang Pilipino, ito ay tungkol rin kung paano na tayo makapag-isip, makipagdiskurso sa ibang tao at kung paano natin pinapatakbo ang bansa.

Para makamit natin ang edukasyong maka-Pilipino, kailangan muna natin bigyan ng pokus ang ating wika. Kaya upang mas pagbutihin natin ang implementasyon ng Mother Tongue sa loob ng paaralan, kailangan muna natin gumawa ng mga materyales na nakasulat sa mga rehiyonal na wika na magiging angkop sa mga estudyante at I-localize ang mga instructional materials sa konteksto ng ginagamitang mother tongue. Bigyan din ng maayos na pag-eensayo ang mga guro at mas maganda rin kung ang mga guro na pinili para magturo ng MT sa klase ay ang mga native speakers ng kanya-kanyang mother tongue. Para sa mga magulang, intindihin natin na hindi dahil ginagamit ang mother tongue sa loob ng bahay ay sapat na bilang isang kasanayan kasi ang pagkakaroon ng MT sa loob ng paaralan ay dagdag ensayo na rin at pagpapahalaga para sa wika para sa bata.

At ang hakbang bilang mga estudyante ay ang pagbibigay-halaga sa ating wika sa loob ng paaralan at makita na ang silbi ng pag-aaral ay hindi lamang makahanap ng maayos na trabaho, kundi mahasa rin natin ang kakayahang mag-isip nang kritikal. Malakas ang kapangyarihan ng wika sa loob ng isang lipunan kasi dahil dito, nabubuo natin ang kakayahan makapag-isip para sa sarili, at para sa bayan.

// ni Erin Obille

Mga Sanggunian:

Arzadon, C. (2023, Agosto 21). [OPINION] On the deletion of Mother Tongue in the Matatag K-10 Curriculum. RAPPLER. https://www.rappler.com/voices/thought-leaders/opinion-deletion-mother-tongue-matatag-k-10-curriculum/

Chi, C. (2024, Enero 13). Explainer: With students’ poor literacy, are all teachers now ‘reading teachers’? Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2024/01/11/2325063/explainer-students-poor-literacy-are-all-teachers-now-reading-teachers

Constantino, R., & Constantino, L. R. (1982). The Miseducation of the Filipino/World Bank Textbooks: Scenario for Deception. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA44320691

Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education? Sprogforum, 7, 15-20.

Daguno-Bersamina, K. (2024, Oktubre 12). Bill ending mother tongue education lapses into law. Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2024/10/12/2392016/bill-ending-mother-tongue-education-lapses-law

Department of Education. (2016, Mayo). Mother Tongue CG. https://www.deped.gov.ph/k-to-12/about/k-to-12-basic-education-curriculum/grade-1-to-10-subjects/mother-tongue-cg/

Ethnologue (2024). https://www.ethnologue.com/country/PH/

Hernando-Malipot, M. (2023, Agosto 10). DepEd launches MATATAG K to 10 curriculum of the K to 12 Program. Manila Bulletin. https://mb.com.ph/2023/8/10/dep-ed-launches-matatag-k-to-10-curriculum

Hernando-Malipot, M. (2023, Agosto 11). ‘Confusing’ Mother Tongue subject removed; to remain as a medium of instruction --- DepEd. Manila Bulletin. https://mb.com.ph/2023/8/10/confusing-mother-tongue-subject-removed-to-remain-as-a-medium-of-instruction-dep-ed

Hunahunan, Lyoid. (2019). Coping With MTB-MLE Challenges: Perspectives of Primary Grade Teachers in a Central School. 6. 298 - 304.

INQUIRER (2023, Septiyembre 5). Use of first language or mother tongue does not work in the Philippines | Inquirer Opinion. INQUIRER.net. https://opinion.inquirer.net/166071/use-of-first-language-or-mother-tongue-does-not-work-in-the-philippines

INQUIRER (2023, Septiyembre 11). Mother tongue subject: Improve, not remove | Inquirer Opinion. INQUIRER.net. https://opinion.inquirer.net/166211/mother-tongue-subject-improve-not-remove

Monje, J.D et al. (2019, Hunyo 27) ‘Starting Where the Children Are’: A Process Evaluation of the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Implementation. Philippine Institute for Development Studies. https://www.pids.gov.ph/publication/discussion-papers/starting-where-the-children-are-a-process-evaluation-of-the-mother-tongue-based-multilingual-education-implementation

Ombay, G. (2024, Oktubre 14). Teachers dismayed over law removing mother tongue in K-3. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/923609/teachers-dismayed-over-law-removing-mother-tongue-in-k-3/story/

Peña, K. D. (2023, Pebrero 8). Government shortcoming failed mother tongue program, lawmaker says | Inquirer News. INQUIRER.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1726422/government-shortcoming-failed-mother-tongue-program-lawmaker-says

Philippine Institute For Development Studies. (2020, Marso 19). Use of mother tongue in teaching facing implementation challenges. https://www.pids.gov.ph/details/use-of-mother-tongue-in-teaching-facing-implementation-challenges

Sampang, D. (2024, Oktubre 13). Solon slams new law ending mother tongue instruction for pupils. INQUIRER.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1992068/solon-slams-new-law-ending-mother-tongue-instruction-for-pupils

Servallos, N. J. (2023, Septiyembre 25). Teachers’ group wants MATATAG curriculum implementation stopped. Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/09/26/2299031/teachers-group-wants-matatag-curriculum-implementation-stopped

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The important thing about me is that I love typologies. I love comparativism, and I love contrasting things and finding out how they differ. When someone points out deep-seated differences between categories I had never even considered as such, I get an almost sexual feeling of contentment and satisfaction.

When someone shines a raking light across various morphological and geneological categories, pointing out how they do and don't map onto each other, I feel like a chorus of frogs singing in the spring.

When I feel styles and aesthetics become soluble and tractable beneath the industrial power of a well-developed technical vocabulary, a bullet-pointed list, I feel as if someone is doing one of those powerwashing videos to the folds of my well-oiled brain.

When someone bullshits unrigorously about how x is different than y, I feel qualia otherwise instantiated only when old friends drink beer by a lake or conjured up for 2.3 unsteady picoseconds in the corpuscle-streaked ventricles of the Large Hadron Collider.

When I found out about the IPA and Ethnologue, I felt I had received a new revelation from God, the third eye burgeoning beneath my sincipital bone.

I love interpreting new things in light of existing categories, and I love it when things blend and complicate types while offering an opportunity to dissect and compare the intricate dance of their components, reaffirming the utility and applicability of the original schema. It makes my brain feel like a Roman being strigiled by his most muscular freedman.

And I vote.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giovani

Giovani: coloro la cui giovinezza significa per gli altri soprattutto che la loro si è allontanata.

M. Augé, [Un ethnologue dans le métro, 1986], Un etnologo nel metrò, Milano, Elèuthera, 2010 [Trad. F. Lomax]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i may or may not be making this poll because i wanna determine which language i should learn.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What language(s) do you think are the closest to Catalan in terms of vocabulary, syntax, conjugation, etc?

Without a doubt, Occitan is the closest language to Catalan. In fact, even until the 19th century, Occitan and Catalan were often considered variants of the same language.

After Occitan, the next closest languages are other members of the Galloromance group: Aragonese, French, Arpitan, and some Gallotalian languages like Piedmontese.

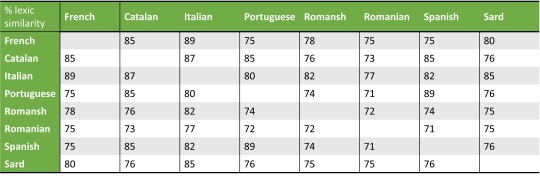

That's in general, taking into account grammar. If we look only at words, the closest (outside of Occitan) seems to be Italian. You can find the percentages in this table (format made by me using the data from Ethnologue):

Highlights to answer your question:

Catalan and Italian: 87%

Catalan and French: 85%

Catalan and Spanish: 85%

Catalan and Portuguese: 85%

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey you! Are you working with a new language in your WIP?

Or do you need to research how different world languages work?

Then do yourself a favour and use ethnologue

It is a website where everything about all languages is documented and constantly kept upt to date. It explains how languages work as a system. What languages are dying. How many people speak which languages. You can select from a menu and research each language you need. And rest assured there are more than 7000 among which to choose, because the aim of the website is to analyse and research and document *all existing lanaguages* even dialects. There are professional linguists that use this and contribute to it.

Guys it's GOOD I promise. I use it a lot for my uni work.

@olive-riggzey may it be of interest?

16 notes

·

View notes