#(coicidence and intentional)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sometimes you hyperfixate on a character for so long you just start to become them. Both intentionally and coincidentally

#like for example#im. kaladins my favprite right#all my friends call me Cal (intentionally to mirror Kal)#I play the flute (coicidence)#i got diagnosed with major depressive disorder (coicidence)#i have dark almlst black hair and im growing it out to be shoulder length (coicidence)#im gonna go to college for bio/premed (btoh.)#(coicidence and intentional)#and. and im taking psychology.#and i can do cool shit with a 6 foot poll (colrpguard)#im like if kaladin was 5'4 and white#stormlight archive#cosmere#the stormlight archive#brandon sanderson#sorchaposting#kaladin stormblessed#not tagging this spoilers because like. we all know hes learbing 5he flute. rifhr.#right..

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, but I think that kind of...makes the point.

Vs (Gunbuster and Nadia, both by Anno)

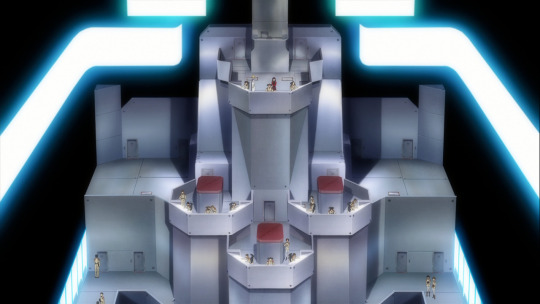

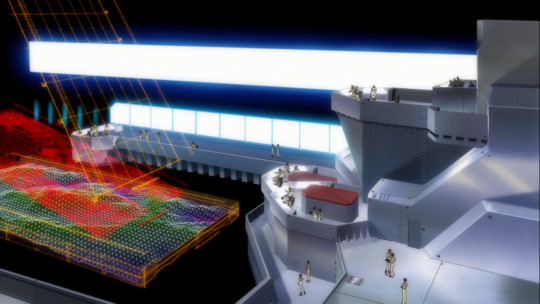

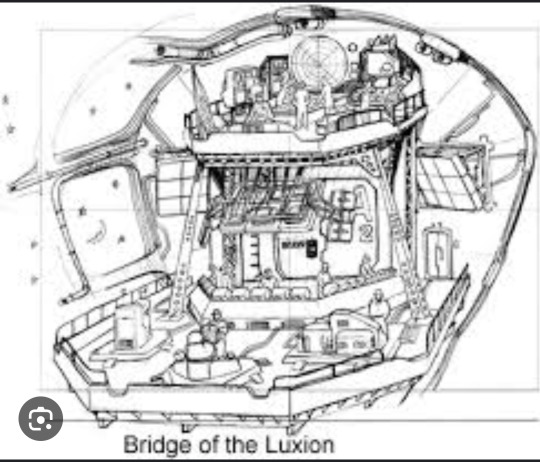

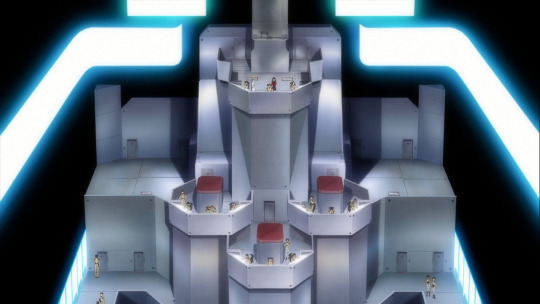

Command structures which have the captain elevated are just...how that works. The extreme exaggeration in Evangelion is noticeable and feels deliberate. It's also much more emphasized than in Gunbuster or Nadia, which don't have multiple long panning shots of these command centers from multiple angles and dramatic lighting like Eva does.

The structure is so large that at scale, individuals are dwarfed and lost in the shot. Rule of cool, yes. But the visual storytelling, how the characters are framed, is also supposed to impact how we perceive the characters and the organization of NERV.

So, to my husband's original observation- it's not just dumb anime nonsense and bad architecture to have the NERV HQ built this way. It's portrayed this was to convey tone and characterization to the audience. And I think that disregarding the fact that the emotionally distant domineering father is placed in that specific spot kind of...I dunno, doesn't give Anno enough credit for the visual language of the series.

Like, Gendo also wears those super reflective glasses- why? It looks cool. But also the eyes are the most emotionally expressive part of a person, and Gendos reflective glasses work as a mask to hide his emotions and thoughts from the audience. Is that just a coincidence too?

Eva is a work that plainly and deliberately is using metaphor to explore its theme. And it feels... dismissive to ignore the visual symbolism within the story.

My husband and I are currently working on the Evangelion rebuild movies.

And the other day (after watching the second one) my husband starts talking about how the control center for NERV doesn't make any sense.

"It's set up like a command bridge, but the height differences are ridiculous. Why do the levels need to be so tall? It would make it so hard for anyone to talk to each other!"

And I'm just like...

"Uh huh. Weird right. It's kinda like Gendo...has put himself up on a pedestal, isolating himself, and making it impossible to communicate with him. Weird. What a weird choice. Why would Anno design it that way?"

#oh its just a coicidence that the distant domineering father was drawn like that#its not an intentional artistic choice?#why not?#why not give anno a little credit here#especially when unlike the christian stuff it like makes sense and aligns with other characterization in the story

294 notes

·

View notes

Note

don’t know if it’s within his control or really an intentional burn // maybe it’s a coicidence but that doesn’t make it any less hilarious

^

1 note

·

View note

Note

https://twitter.com/bbang0415/status/1497076197850636291?s=21

Their shirts are also matching, maybe a coincidence

Another anon

NCheoDol/status/1497076796533080066?s=20&t=3IFzRYb3fMA8IydvT_A8jA I don't know if it's a coincidence or intentional...

Another

some fans are thinking jaehyun chose that pic with hearts bec maybe he's the one who took it also the matchy hoodie doyoung is wearing there

---------

Link, Link2 - Lmao!

In all honestly, usually I dismiss stuff like this, but it's Jaehyun we are talking about, there is a bigger chance it's not a coicidence tha otherwise.

Yeah, we can't be sure, but I think it was Jae who chose the pics because the stuff usually uses the official photos, why would they waste time on digging through Do's IG and asking him for pics in higher resolution. And if Jae did the process of choosing, then there was a design behind it, a reason for each choice. The blue sweater is a match to Jae's blue cloudy hoodie. Hence, the heart picture could be a match as well.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

cr theory time so I can be smug if I’m right what ifff that creepy ass sentient city bullshit thing is the chained oblivion and it was using vokodo for his weird ass memory mist and that’s how the angel of irons cult got brainwashed and molly used to be an angel of irons cultist and then he got over misted by vokodo and turned into mollymauk

like there’s definitely a connection there between the chained oblivion messing with memory/brainwashing, the people of vo, and molly’s waking up with no idea who he was. there’s a lot of memory/mind fuckery going on in this campaign and it definitely feels intentional like... yasha’s missing time is canonically related and caleb’s missing time is probably coicidence, but like. there’s something there I’m pretty sure.

#brinn watches critical role#coming off the high of being basically right about jeremy tesla yeah sure technically it was babbage but technically fuck that I'm right

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fact all these spsicious coicidences are happening shortly after Biden became president kinda furthers the truth of the election being tampered with.

This all looks very intentional

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

soulmate au pretty please? i'm such a trash for soulmates au😭😭😭😭 and also its up to you how they will discover that they are each other's soulmate~^^

DFJAKLFDSJL same me too!!!! I love the soulmate AUs and there’s so many I’ve been wanting to do for awhile!!

I think the one I’ll be doing today though is one that’s at least fairly popular? I’m not quite sure but I’ve seen it around before in other various AUs and fanbases.

Anyhow, thank you, have a wonderful day and enjoy!!!

———————————————————————————————————–

Black and white.

That was all the world was to Jumin.

The very moment he was able to see he only saw those two colors, dull, bleak, and never-ending.

He couldn’t even ask his father.

For not even he knew.

But Jumin saw throughout his life the numerous women that would enter his father’s life to leave with wads of cash engrossed in their grip and his heart dangling by a string.

And each time they’d snip whatever string, and let it shatter to the floor.

Not even with his mother was Mr. Han able to see the slightest hint of color.

Why he still chased after the relationship regardless remained an utter mystery to Jumin.

For it only led the family into a near catastrophe.

Yelling and screaming.

That took up most of his memories when it came to his childhood, his head peeking from the door of his bedroom to see his parents fighting with one another with such sheer anger he thought they may burst.

He had almost been surprised to learn this wasn’t normal.

But as time went on, things began to click into place.

As well as the fact that history would only repeat itself, with him.

Many women would enter his life either on business trips or by pure ‘coicidence’, their voices honeyed, and intentions surface deep.

They only wanted his wealth, not truthfully him.

It was always what he had.

And so the strings in his mind became to tangle into a hideous web, a wall reaching the clouds being built around him.

For each time they entered his life, everything remained blank.

Colorless.

Until the most amazing thing happened.

You.

It had been a typical day, his gaze focused as he entered the C & R building, muted sounds of conversations drifting past his ears.

He came to the elevator, the small cluster of people preparing to make their way out as the door opened.

One of those people, being you.

You all began a shifting with him entering and the rest of you leaving, yet as you left you felt your arms brush against the other.

And the world unveiled itself.

Color.

Blues, yellows, purples, reds, greens, oranges, and all in between burst in his eyes a symphony of shades revealing itself to him.

He nearly collapsed at the revelation, his knees threatening to buckle as he slammed against the

And as he turned back he saw the same thing for you.

You had staggered back, jaw dropped and tears stinging the edges of your vision, staring back at him, both of you preparing to approach each other when the elevator doors shut.

He was stopped just as it closed, cursing beneath his breath, a low rumble emanating in his throat.

He didn’t even take a moment to acknowledge Jahee, erupting out the door leading to the stairs, running as if his life depended on it.

And in a way, it did.

Yet as he made his way down he heard the door from down below slam opened as well.

And as he came halfway he came face to face with his soulmate once again.

You.

He was breathless, his shoulders heaving as he gave the widest smile he had ever shown, his heart threatening to jump out in his excitement.

“Um…h-hello.” He greeted sheepishly, reaching out a hand for you to shake. “I-I’m Jumin Han.”

“Y-Yeah most people already k-know that.” You flushed, laughing nervously as you returned the gesture, your fingers lingering in their entwinement a moment longer than usual.

As though neither of you really wanted to let go at all.

“D-Didn’t really expect someone so…so…” You couldn’t even come up with the words in your bewilderment. “I mean…I just came here for an interview!”

“I just…I was simply coming in for work.”

“Guess we both got surprises then?”

He nodded, a warmth blossoming inside of him as your voice became more and more akin to that of a symphony, an odd sort of kindness in your expression he had never seen before.

He didn’t want it to go away.

“That is…one way to put it.”

“In a good way?”

He let out a heavy sigh, a joy he hadn’t thought possible welling inside of him.

And he knew that only happiness awaited him.

And he couldn’t wait.

He couldn’t wait for a future with his soulmate.

A future with you.

“You have no idea.”

#Jumin#Jumin Han#Mystic Messenger#Mystic Messenger Jumin#Mystic Messenger Jumin Han#Jumin Mystic Messenger#Jumin Han Mystic Messenger#Jumin x Reader#Jumin Han x Reader#Reader Insert#Shipfic#Fluff#Jumin x You#Jumin Han x You#You x Jumin#You x Jumin Han#MC x Jumin#MC x Jumin Han#Jumin x MC#Jumin Han x MC#Jumin Fanfic#Jumin Han Fanfic#Jumin Fanfiction#Jumin Han Fanfiction#Fanfic Jumin#Fanfic Jumin Han#Fanfiction Jumin#Fanfiction Jumin Han#Mystic Messenger Fanfic#Mystic Messenger Fanfiction

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do Religion and History Conflict? -- Temple and Cosmos Beyond this Ignorant Present -- HUGH NIBLEY 1992

Do Religion and History Conflict?

A true philosopher can no more pass by the open door of a free discussion than an alcoholic can pass by the open door of a saloon. Since my hosts have been kind enough to invite me to say what I think, the highest compliment I can pay to their tolerance and liberality will be to do just that. This is not going to be a debate. I would be the most unteachable of mortals if at this stage of life I still believed that one could get anywhere arguing with a dialectician. One might as well attempt to pacify or intimidate a walrus by tossing sardines at him as to bate a philosopher with arguments. I have accepted your kind invitation because I think the subject is worth discussing.

“Do Religion and History Conflict?” Only a philosopher would word a question so strangely. If history and religion are different things, as the question implies, isn’t comparing them like comparing a rose and a submarine, or might we not ask as well whether free trade and tapdancing conflict? All things—whether ideas or concrete objects—compete for our attention, but that is plainly not the kind of conflict our questioner has in mind. Nor are we asked whether the laws of history and religion conflict. Such laws as we have in history—fundamental principles such as propounded by Thucydides or Buckle or Spengler—are simply generalizations based on insight and analogy: there is nothing rigorous or binding about them. Furthermore, your religion may conflict with my history and my religion with your history; but for that matter your religion and mine probably conflict, as do your history and mine.

Still, I think we can agree that the idea behind the question is clear: does the story of man’s life as taken from the documents, that is, his history, resemble the life story of the race as taught by revelation, i.e., in holy scriptures? The question is valid for all Christian sects and for non-Christian religions as well. The alternative to the general question is a chaos of special problems. Every church comes before the world with certain basic historic propositions peculiar to itself. Every church may be judged by those propositions when they are clearly stated: if a group announces that the end of the world is going to come on a certain day or, like Prudentius, predicts victory in a particular battle as proof of its divine leadership, or claims like the Mormons that there once was a prophet named Lehi who did such and such, we can hold that church to account. Incidentally, it will not do to project those accepted propositions into inferences and corollaries of your own, and then criticize their supporters in the light of those inferences and corollaries. We must be very careful to determine exactly what is claimed, by exactly what particular group, and then to determine exactly what happened and is happening. At this point the discussion breaks up into thousands of special topics, none of which could be handled here tonight.

The religions of the world take their stand on history to a far greater extent than is commonly realized. Christianity is by nature apocalyptic—a definite concept of world history is implicit in its teachings, its scriptures are at least half history, and it rests its whole case in the last analysis on the fulfillment of prophecy. My own church by its very name takes a definite historical stand: these are the “last days,” not the end of the world, but a time of continual crisis and mounting world conflict accompanying the “wasting away of the nations.” I would like to spend all the time in an historical vindication of my religion: but no general conclusions can be drawn from one personal case. Something more general is indicated.

In civilized societies it is customary for educated people to carry around in their heads two images of the past, present, and future world—the one religious, the other secular. Here we have two drawings of the same landscape: are they identical, is there a general resemblance between them, or are they in hopeless conflict? If one has attended a liberal Sunday School, the two pictures will tend to coincide because they have, conscientiously, been made to coicide; the same is true if one has been trained in a fundamentalist school or college. It is apparent that both pictures are highly adjustable—there is an orthodoxy and a heresy in history as well as religion. History is as much what a man believes as his religion is. History vindicates the proposition that God loves the Jews; with equal force, if you want it that way, it vindicates the proposition that he hates them. History has long been taken as a superbly convincing illustration of the working out of the principle of evolution in human affairs; today some scholars see in it a smashing refutation of any such idea. History is the story of man’s progress or his frustration, depending on how you want to read it.

If we are to judge our two pictures on the basis of artistic merit, that is, of subjective appeal, we are under no obligation to declare either one the better picture, nor, on artistic grounds, is there any reason why they should look alike. If, on the other hand, we are judging for accuracy (and that is what is here clearly implied), there is no point in comparing the pictures with each other; we must instead compare both with the original model. At once the nature of tonight’s loaded question becomes apparent. For the obvious intent of the question is to test religion’s claims in the light of historical discovery, or as the newspaper phrased the question, “Can religion face its own history without flinching?” There is no hint that history might flinch in the face of religion (as some historians have): the question proposes a beauty contest in which one of the contestants has already been awarded the prize, a litigation in which the prosecuting attorney happens to be the judge. History is above the storm; the only question is, Can religion take it?

That won’t do. We cannot assume at the outset that either picture is perfect. We have no right to treat “history” as the true and accurate image of things. Like science and religion, history must argue its case on evidence. This body is like a jury: every member must do his own thinking and make up his own mind (that is the beauty of these meetings, we have been told), but only after viewing all the evidence. This is a staggering assignment, but no one can evade it and still form an intelligent opinion. Professor W. S. McCulloch, the authority on the mechanics of the brain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has written: “[Man’s] brain corrupts the revelation of his senses. His output of information is but one part in a million of his input. He is a sink rather than a source of information. The creative flights of his imagination are but distortions of a fraction of his data.”1 In other words, we all receive information much better than we report it; so much so, that however bad the evidence may be, it is always better than any man’s report of it. Every juryman must examine and, if you will, distort the data for himself, whether we are dealing with special or general problems of history. The prospect is terrifying—and it is the historian, not the prophet, who flinches.

What we are up against may be illustrated by the case of a speaker in this series who maintained that there can be no true religious knowledge because one can never produce reliable evidence for it. He was such a ferocious stickler for evidence (and in that I enthusiastically agreed with him) that when he said three or four times that the Egyptians in 5,000 years produced nothing but the sheerest nonsense in religion and insisted on using that supposed fact as evidence for his most questionable claim (i.e., that religious teachings need not be true to be valuable), I could not help asking myself on what evidence he could possibly rest such a statement? Five thousand years is no small slice of history, and the Egyptians have left us a very respectable heap of documents. I remembered that a severe and exacting Egyptologist, T. E. Peet, had written:

As long as our ignorance is so great, our attitude towards criticism of these ancient literatures must be one of extreme humility. . . . Put an Egyptian [or Babylonian] story before a layman, even in a good translation. He is at once in a strange land. The similes are pointless and even grotesque for him, the characters are strangers, the background, the allusions, instead of delighting, only mystify and annoy. He lays it aside in disgust.2

Our speaker was properly disgusted with the Egyptians, but to charge them with uttering nothing but nonsense for 5,000 years really calls for a bit of proof.

At the first opportunity I hastened to the stacks of your excellent library, hoping to find treasures indeed, and there discovered just one Egyptian book—a religious work, incidentally, which I value very highly. I looked for other Oriental treasures, the heritage of great world civilizations—and found nothing! Surely, I thought, we can’t talk about history intelligently and leave all that stuff out. But that is precisely what we do! And that raises the all-important question for the student of history: Is there not some way of obtaining a reliable impression of the past, or of building a plausible structure of history without having to examine all the evidence? The problem that concerns our historians today is that of reducing the bulk of evidence without reducing its value. The futility of the quest is a corollary of the oft-proved proposition that the quality of history is a function of its quantity: the more information we have, the better our picture, and the rule is in no wise vitiated by the fact that some information is more valuable than other information.

The historian’s problem was correctly formulated by the scholars of the Renaissance and Reformation. These men suddenly had an enormous heap of documents dumped in their laps. They were tremendously excited about the new treasure and saw immediately that the whole pile would have to be gone through piece by piece and word by word: there could be no question of priority or selectivity or elimination, because there is no divination by which one can tell what is in a document before one has read it. This is a lesson which modern scholars have forgotten. The only legitimate question is: “By what method can one properly examine the greatest possible amount of material in a single lifetime?” The challenge has small appeal to a hurried and impatient generation like our own. We look for easier and quicker solutions, as did the Sophists of old. And like them we find those solutions in the endless discussions and expensive eyewash of the university. Consider what goes on in the history business.

1. First, the academic mind wants neatness, tidiness, simplicity, order. It is impatient to impress an order upon nature without waiting for the real order of nature to become apparent. Historical events occur in an atmosphere of perplexity. Whether we are dealing with unique events or characteristic and repeated ones, as in culture-history, we are given no respite from the unexpected: we never know what hit us. The historian must always step in and impose order after the event. He is like a general who, having all but lost his shirt in a campaign, blandly announces when it is all over: “We planned it that way!” History is all hindsight; it is a sizing up, a way of looking at things. It is not what happened or how things really were, but an evaluation, an inference from what one happens to have seen of a few scanty bits of evidence preserved quite by accident. There is no such thing as a short, concise history of England, any more than there is an authentic three-minute version of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. One might construct such a thing, and it might be a work of art in its own right, but it could only be a parody of the real thing—a pure fiction.

As I read the journal of Samuel Sewall, the letters of Cicero, the memoirs of Joinville or Froissart or Xenophon or Ibn Battuta, I cannot but feel myself getting involved in exciting and vivid situations that will forever be as much a part of my experience as, say, the invasion of Normandy (I still remember what I read in Normandy as vividly as what I saw there). But if I read a paragraph or a sentence or two about each of the above in a college textbook, I have really had no experience at all. Yet it is not in those great neglected writers that the most valuable evidence is found, but rather in such completely neglected trivia as letters, diaries, notebooks, ledgers, etc., which few historians and no others ever care to look at.

2. The modern college teaches us, if nothing else, to accept history on authority. Yet at the end of his life the great Eduard Meyer (who wrote a history of the Mormons, incidentally), marveled that he had always been most wrong where he thought he was most right, and vice versa. No man of our time had a broader view of world history than Professor Breasted, or was ever more dogmatically sure of himself or, in the light of subsequent discoveries, more completely wrong. To be open-minded in history one must be working constantly at one’s own structure of history, not passively accepting any secondhand solution or textbook opinion that floats down from the shining heights, as crabs and mollusks in the depths gratefully receive the dead and predigested matter that descends to them from luminous realms above. Everybody knows some history, nobody knows very much. Your strengwissenschaftliche Geschichte (“strictly scientific history”) is nowhere to be found. Ranke tried for it, but I believe with the historian Frowde that our best historian was Shakespeare.

3. The insights of men like Taine, Mommsen, or Bury are not to be despised. Do not for a moment think that the only reliable evidence comes from brass instruments. But insight offers no escape from evidence. Insight requires in fact to be properly checked by the most exhaustive evidence of all—that which comes only by constant, intimate, lifelong familiarity with the sources. There is no more merit in armchair humanities than there is in armchair science: the learner must come to grips with the real thing at first hand; he must run the evidence to ground as in a laboratory, and never be content with the fourth-hand hearsay of a textbook or the private evaluations of a translator.

4. The most popular attempt to grasp history at a gulp is the Cook’s Tour, for which Mr. Toynbee’s lumbering and laboring rubberneck bus is at present in great demand—though no one really seems to enjoy riding in it. Here the interest is in the monumental, the routine, the conventional, the accepted. The student is a tourist, a spectator, always detached, never allowing himself to become emotionally involved except at the prescribed stations where the guidebook instructs him to swoon. At best our college humanities are a sentimental journey, a scenic-postcard world of the obvious and theatrical: the Great Books, the Hundred Best Poems, the Greatest Works of the Greatest Minds, etc. What makes the study of history possible today I call the Gas Law of Learning, namely, that any amount of information, no matter how small, will fill any intellectual void no matter how large. It is as easy to write a history of the world after you have read ten books as after you have read a thousand—far easier, in fact. This is the historian’s dilemma: if his view is sweeping enough to be significant, it is bound to be inadequately documented; if it is adequately documented it is bound to be trivial in scope. It is a cozy and reassuring thing for student and teacher alike to have our neat authoritarian College Outline Series Syllabi of Western Civilization, Surveys of Great Minds, and what not, to fall back on. But please don’t point to these pedestrian exercises in skimming and sampling and try to tell me that they are a valid refutation of the prophets!

5. To handle problems requiring data beyond the capacity of students and educators impatient to shine, the ancient Sophists devised certain very effective discussion techniques. In these, the most important skill was that of presenting evidence by implication or inference only. Since it is quite impossible in a public discourse (or in print, for that matter) to put all one’s evidence on display, one must be allowed on occasions to present one’s knowledge merely by inference. The Sophists seized upon this welcome path of escape from drudgery, and by the arts of rhetoric made of it a broad highway to successful teaching careers. A limited use of jargon is indispensable in any field: having solved for “x,” we do not have to derive “x” every time it is mentioned, but simply to indicate it by a symbol, such as those useful keywords commonly used to power historical discussions: the Medieval Mind, Sturm und Drang, the Frontier, Hellenism, the Enlightenment, Puritanism, the Primitive, Relativity, etc., each of which is supposed to set a whole chorus of bells chiming in our heads—the echoes of deep and thorough reading. But by a familiar process these labels are no mere labels any more; they have become the whole substance of our knowledge. The student today has never solved for that “x” about which he talks so glibly—he has got its value from an answerbook; the cue word is not just a cue; it is now the whole play. The stock charge against the philosophers in every age has been that they have made themselves experts in the manipulation of labels to the point where they live in a world of words. The art of implying the possession of certain knowledge without actually claiming it has become one of the great humanistic skills of our time, in Europe as well as America. Without it the teaching of history would be almost impossible.

My own self-confidence in sounding off on historical matters need not reflect any solid knowledge at all, but may well be the product of a careful grooming, a calculated window dressing. Today the typical academic historian does most of his training before a mirror. The modern world, like the ancient, is a world peopled largely by zombies. Occasions like this one tonight are not meant to teach but to impress. If it was knowledge we were after, we would all at this time be perusing the evidence, not listening to me.

The confusion of discussion-born ideas with evidence is the root of much trouble in education today. People wishing to be liberal demand that their ideas be given the authority of evidence with the general public and in the classroom. If we refuse to accept those ideas, however hackneyed and unobjectionable they may be, as legal tender in an economy where only evidence passes as such, they complain that their ideas are being held in contempt and that they are being persecuted—which is not true at all.

6. What about those great historical systems which the giants have erected from time to time—do not such give a faithful picture of the world? Alas, system is the death of history! The great historians have all been random readers. Werner Jaeger has said, “It must never be forgotten that it was the Greeks who created and elaborated not only the general ethical and political culture in which we have traced the origin of our own humanistic culture, but also what is called practical education and is sometimes a competitor, sometimes an opponent of humanistic culture.”3 One builds systems by excluding as well as including. When you choose to build one structure rather than another you are not merely rearranging materials in new combinations, you are emphasizing some things at the expense of others. Excluding or suppressing evidence is dangerous business, and what makes it doubly dangerous is the way in which systems of history by their very exclusiveness convey a powerful and perfectly false sense of all-inclusiveness. The product of the System is the closed mind, the student who has taken the course and knows the answers, who has been systematically bereft of the most priceless possession of the inquiring mind—the sense of possibilities.

“The Bible excels in its suggestion of infinitude,” said Whitehead and, as a friend describes it, “suddenly he stood and spoke with passionate intensity, ‘Here we are with our finite beings and physical senses in the presence of a universe whose possibilities are infinite, and even though we may not apprehend them, those infinite possibilities are actualities.‘ ” Later he added, “I doubt if we get very far by the intellect alone. I doubt if intellect carries us very far.”4 The study of history in the schools today, with its “intellectual” orientation, effectively stifles that very sense of possibilities which it is the duty of history before all else to foster. For every door it opens, our modern education closes a thousand. We cannot insist too emphatically on the endless mass, variety, detail, and scope of historical evidence; every page of every text is a compact mass of a thousand clues, and every reading full of new and surprising discoveries. That is the essence of history, and the modern academic presentation completely effaces it. The modern scholar is eager to reach his conclusion, get his degree, and stop his investigations before there is any danger of running into contradictions. From a safe and settled position he wants only to discuss and discuss and discuss. The via scholastica is well marked: first one takes a sampling, merely a sampling, of the evidence; then as soon as possible one forms a theory (the less the evidence the more brilliant the theory); from then on the scholar spends his days defending his theory and mechanically fitting all subsequent evidence into the bed of Procrustes.

7. But surely there is a general overall picture of history, or some really basic points, upon which a massive consensus exists. Surely the verdict can be imparted to students in a few lessons, and it must be fairly reliable. There is a charming study by the Swede Olaf Linton on the basic certitudes of church history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—what he calls the Consensus with a capital “C.” Mr. Linton shows us how the consensus changes with time and circumstances just as completely and just as surely as the fashions in women’s hats. The Homeric question furnishes us with a good illustration of present-day consensus. What we call higher criticism is the application to the Bible of methods of textual criticism developed in the study of the Homeric problem. That problem is really far simpler than the biblical (there is hardly a book in the Bible that is not as mysterious as Homer), yet after 200 years of intensive investigation where do we stand? Listen to Professor Wade-Gery of Oxford: “Homer, who wrote the Iliad as I believe sometime in the eighth century . . . lived (as I believe) in Chios, and knew the Eighth City of Troy. He was (as I also believe) a man of exceptional genius. . . . I feel sure that almost all which makes the Iliad a great poem is the poet’s own creation.”5 And listen to Professor Whatmough of Harvard in the same issue of the same journal:

Nothing is, or could be, more puerile than the notion that the Iliad could possibly have been composed by one man. . . . The complex descent (rather than “origin”) of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey is as certain as anything can be in this very uncertain world. . . . I know [of] no competent linguist . . . whose knowledge of Greek and Greek dialects I respect enough to quote his name, who holds any other opinion. . . . To use the term author or authorship . . . is simply to sin against the light.6

Note it well: “As certain as anything can be.” Yet a host of big names are quite convinced of the opposite! The consensus has its fads and fashions like everything else.

As for the scientific consensus, with all its vaunted objectivity, let us hear Whitehead again:

In those years from the 1880s to the first war, who ever dreamed that the ideas and institutions which then looked so stable would be impermanent? . . . Fifty-seven years ago . . . I was a young man in the University of Cambridge. I was taught science and mathematics by brilliant men and I did well in them; since the turn of the century I have lived to see every one of the basic assumptions of both set aside; not, indeed, discarded, but of use as qualifying clauses instead of as major propositions; and all this in one life-span, the most fundamental assumptions of supposedly exact sciences set aside. And yet, in the face of that, the discoverers of the new hypotheses in science are declaring, “Now at last, we have certitude“—when some of the assumptions which we have seen upset had endured for more than twenty centuries.7

And but a few months ago Professor McCulloch wrote:

At last we are learning to admit ignorance, suspend judgment, and forego the explicatio ignoti per ignotius—”God”—which has proved as futile as it is profane. . . . So long as we, like good empiricists, remember that it is an act of faith to believe our senses, . . . and that our most respectable hypotheses are but guesses open to refutation, so long may we “rest assured that God has not given us over to thraldom under that mystery of iniquity, of sinful man aspiring into the place of God.”8

I can answer the question, “Do religion and history conflict?” for myself, but not for anyone else. At present, my religion and history do not conflict, as once they did. Well, you say, of course they agree because you make them agree. That is not entirely true. There are controls. Within the last three or four years leading Jewish and Christian scholars have been forced to relinquish a concept of history which they had painfully built up through the decades to an almost perfect consensus. Some of them put up a magnificent fight, but in the end the evidence was too strong, and one by one they gave in. It is a healthy sign when religion and history conflict: it means that they are not being bent wilfully to force them into agreement. In most historical fields the difficulty of the languages in which the sources are written is enough in itself to guarantee the minimum of intellectual integrity in the researcher: the documents simply refuse to speak unless one approaches them with a really open mind and is willing to swallow his pride and suppress self-will. In much the same way the rigorous demands of mathematics guarantee a measure of honesty in any scientist who is equipped to work in a field.

But unfortunately there are no such controls in those more socialized fields of learning which, for that very reason, have completely banished the older disciplines from our secondary schools and supplanted them at the university by pretentious techniques of discussion and pseudo-scientific “quantification of the obvious.” In such an atmosphere it is futile to attempt a serious discussion of history.

I believe my history and religion agree in a way that is objective enough to justify my conviction that the agreement is not entirely the result of my own manipulating. But whether this agreement is significant or not must be decided by everyone for himself, on his own examination of the evidence. As to the general question, “When do we flinch?” the answer is: Wait until history comes up with all the answers, or with any answer we can be entirely sure of—then we will know whether to flinch or not. Meantime, it is the historian’s duty (for it is he who appeals to an uncompromising objectivity) to flinch every time an answer of his proves defective—which is, roughly, on the hour every hour.

Does life on the moon resemble life on Mars? It is a good question, but premature. When I was a little boy we used to sit in a tent on hot summer afternoons and debate loudly and foolishly on just such lofty themes as this one. I think we all felt vaguely uncomfortable about the whole thing, and that made us all the more excitable, dogmatic, and short-tempered. The trouble was that we were not yet ready; we did not have the necessary knowledge. But when would we be ready? Are we ready yet? If not, we should stop playing this game of naughty boys behind the barn, smoking cornsilk and saying damn and hell to show how emancipated we are. It is much too easy to be a “swearing elder”: knowledge is not so cheaply bought. We are not free to discuss any imaginable question simply because we say we are. I am not permitted to discuss botany with anybody, at any time or place; it is not the jealousy of a reactionary society or the dictates of a narrow church that cramp my style—I just don’t happen to know anything about botany. Prejudice, says Haldane, consists in having an opinion before examining all the evidence. If anyone draws any conclusions but one here tonight, they must needs be prejudiced conclusions. If we have gathered here to read lectures to each other or to the Mormon Church, we might as well spare our breath; or if you are looking for a stick to beat the Church with, my advice is, leave history out of it—it will come apart in your hands. For our knowledge of the past is too trivial to serve as an effective instrument in real situations—that is why it is often appealed to but never actually used.

What do we have then? Well, I have a testimony: I may be ignorant, but I am not lost. Socrates counted a life well spent that ended only with the discovery that he knew nothing. That was not a figure of speech or a clever paradox: that was his solemn testimony delivered in the hour of his death. And if the most profitable activity of the mind is that which leads to the discovery of its own ignorance and ineptitude, we can all take heart in the thought that we have not entirely wasted our time in coming here tonight. At this point we can begin the study of the gospel; there is no further need for waiting around until “history” can make up its mind.

Notes

1.

W. S. McCulloch, “Mysterium Iniquitatis of Sinful Man Aspiring in the Place of God,”

Scientific Monthly

80 (1955): 39.

2. T. E. Peet, A Comparative Study of the Literatures of Egypt, Palestine, and Mesopotamia (London: Schweich Lectures, 1931), 6, 12-13.

3. Werner Jaeger, Paidea, 3 vols. (New York: Oxford, 1945), 1:317.

4. Lucien Price, “To Live without Certitude, Dialogue of Whitehead,” Atlantic Monthly 193 (March 1954): 58-59.

5. H. T. Wade-Gery, “What Happened in Pylos?” American Journal of Archaeology 52 (1948): 115-16.

6. Joshua Whatmough, “Hosper Homeros Phesi,” American Journal of Archaeology 52 (1948): 45-46.

7. Price, “To Live without Certitude,” 58; cf. Lucien Price, “Visit and Search, Dialogues of Whitehead,” Atlantic Monthly 193 (May 1954): 53: “I had a good classical education, and when I went up to Cambridge early in the 1880’s my mathematical training was continued under good teachers. Now nearly everything was supposed to be known about physics that could be known—except a few spots, such as electromagnetic phenomena which remained (or so it was thought) to be coordinated with the Newtonian principles. But, for the rest, physics was supposed to be nearly a closed subject. Those investigations to coordinate went on through the next dozen years. By the middle of the 1890’s there were a few tremors, a slight shiver as of all not being quite secure, but no one sensed what was coming. By 1900 the Newtonian physics were demolished, done for! Still speaking personally, it had a profound effect on me; I have been fooled once, and I’ll be damned if I’ll be fooled again!”

8. McCulloch, “Mysterium Iniquitatis of Sinful Man,” 36, 39.

0 notes