#晏宁

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

DOWNLOAD [Single] BDF2022 / 哔哩哔哩舞蹈嘉年华 - Various Artists [MP3-320KB]

0 notes

Photo

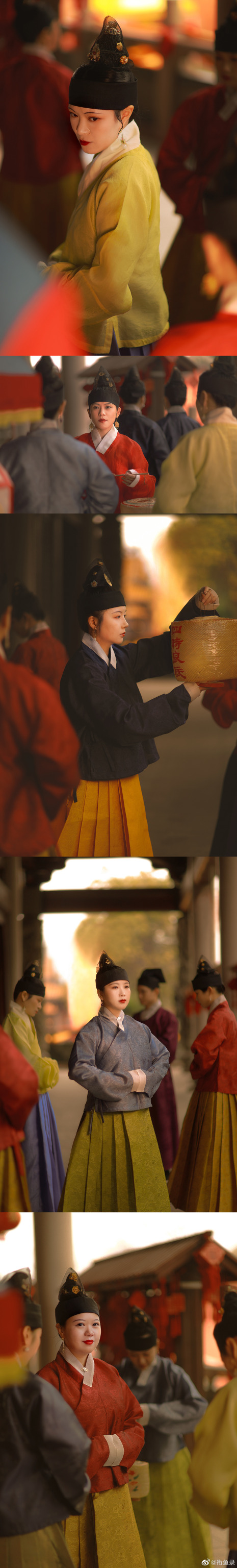

【历史文物参考】

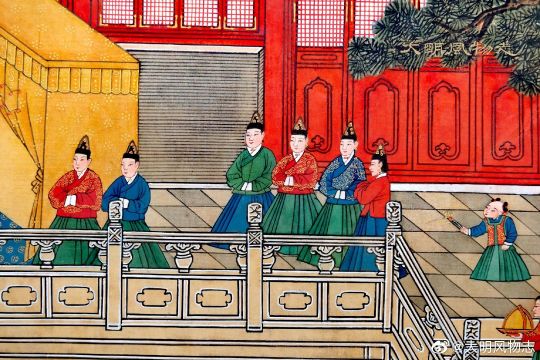

Chinese Ming Dynasty Painting(1485 CE):【明宪宗元宵行乐图/Ming Emperor Xianzong Enjoying the Lantern Festival (part)】showing court lady in the ming dynasty

※ Women with gold patterns in Hanfu (top) had titles/rank in the court of the Ming Dynasty, and they may be imperial concubines, princesses, etc.

[Hanfu · 汉服]Chinese Ming Dynasty Chenghua era(1465-1487 AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle

【About horsehair skirt (马尾裙) petticoat】

A horsehair petticoat (马尾裙) is a petticoat that is worn under the skirt to give it a puffy appearance. This kind of petticoat came from Korea Joseon at that time.

❗ However, it would be wrong to say that the entire outfit above is Korean origin as someone claim.

In Ming Dynasty record "寓圃杂记/Yu Pu Notes" By Wang Kai王锜 emphasizes that this style of clothing (马尾裙horsehair petticoat) is a kind of ominously strange clothing , which is what the ancients called "服妖(A derogatory term that describes people wearing weird clothing is bad symbol)". It is only popular among rich and uneducated people, and will let decent people look down on, the original words are " 然系此者惟粗俗官员、暴富子弟而已,士夫甚鄙之,近服妖也 "

Horsehair petticoats are popular in Beijing. Demand was low at first, and local production was impossible and unnecessary. They are all imported from Korea Joseon. When it becomes popular, even men like to wear horsehair petticoats under their robes, and the demand and market will naturally increase, so localized production began. But the number of horses is limited, and the most important raw material, horse hair, is not easy to obtain.

So some people went to the army camp to steal the horse hair of the army horse, which made the army horse look thin and bad.

❗In the Early Emperor Hongzhi era,the officials reported these incident to the Emperor Hongzhi(1470-1505)of the Ming Dynasty said”京中士人好著马尾衬裙,因此官马被人偷拔鬃尾,有误军国大计。乞要禁革”Saying that such behavior is not good for the country and suggest to ban horsehair petticoat. So Emperor Hongzhi make an order to banned people wearing Horsehair petticoats

Since then, this horsehair petticoat gradually disappeared from China history

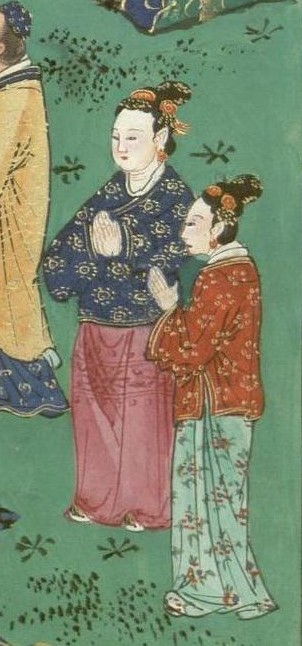

❗ It is worth mentioning that even in the period when horsehair petticoats were popular, not everyone wore horsehair petticoats, as shown in the book "释氏源流应化事迹" in the Chenghua era of Ming Dynasty (AD 1465-1487): ( Women that not wear horsehair petticoats)

After Emperor Hongzhi banned the wearing of horsehair petticoats (back to the silhouette of Hanfu in the Ming Dynasty), as shown below

Murals in the tomb chamber of Zhengde period (1506-1521) - Jiajing period (1522-1566)::

_______

💡 Produce: @衔鱼录

📸Photo: @超级方便MAN

🎥Post-production : @还是叫我雪影吧

🔖Hanfu Research: @玩泥巴的豆角 @邈邈阁的颜掌柜

🧚🏻 Model : @还是叫我雪影吧 @曾嚼子 @记不住密码的小基崽 @NanFu_南赋吖 @玩泥巴的豆角 @纭澈 @言言衍晏 @子可_POTTERY @祁祁萝祁萝贰祁

💄Makeup Director: @还是叫我雪影吧

🧵Tailor: @邈邈阁的颜掌柜

🏮Lantern provider: @纭澈

CC organization: @南宁汉服小组 @汉洋折衷bot @大朙时尚搭配频道 @大明穿搭bot @说给大明服饰

🔗微博:https://weibo.com/3962795866/MrDftbHIT

_______

#chinese hanfu#Ming Dynasty Chenghua era(1465-1487 AD)#hanfu#chinese traditional clothing#chinese fashion history#China History#chinese#historical fashion#historical hairstyles#Chinese Costume#chinese culture#hanfu accessories#hanfu history#Zhengde Emperor era(1506-1521)#Jiajing Emperor era(1522–1566 A.D)#《释氏源流应化事迹》#寓圃杂记/Yu Pu Notes#明宪宗元宵行乐图/Ming Emperor Xianzong Enjoying the Lantern Festival#汉服#漢服#Horsehair petticoats

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Novels

盛妆山河 Shengzhuang Mountain and River

��医世子妃:病弱世子他不经撩 The Doctor Prince's Concubine: The sickly prince is not easy to tease

女将守则:我为皇上打天下 Female General’s Code, Fight for His Majesty

《镜中蔷薇》作者:君子以泽 Roses in the Mirror

重生成偏执吸血鬼的小娇妻 Reborn As A Little Fiancée Of Paranoid Vampire

书生有种 The Scholar Has Kindness

朝暮入我心 Morning and Evening Into My Heart

嫁給清冷表哥 Marrying a Cool Cousin

被清冷表哥嬌養後 After Being Pampered by Her Cold Cousin

0 notes

Text

批評中的歷史

劉鳳翰 文星叢刊 169

史學家劉鳳翰辭世

hanreporter.blogspot.com

五胡亂華之後,東胡族的一支,散居在遼河上流,潢水附近。他們

逐水草而居,漁獵而食,過著標準的漁獵與游牧的生活。經過五六

世紀的發展,到了隋唐的時候,勢力漸大。唐朝初年,雖設 松漁

都督府 來管理他們,但因為他們流居不定,所以叛服無常。

正史的記載,最早見於 魏書,在 魏 道武帝 時,散居在 和龍 以北

數百里土地上。魏獻文帝 以後,才開始有部落組織,當時是事奉

魏朝的諸部落中,最小的一個。

契丹 活動的地方,就在大漠南北廣大的草原上。那裡氣候寒冷,

雨量稀少,山重水濁,土地瘠鹵,黃茅百草,彌望無極。「天蒼蒼

地茫茫 風吹草低見牛羊」真是她最好的素描。

她的漁獵游牧生活,使人們兵強馬壯,勇於戰鬥,真是「人自為戰如

熊羆」因此鐵騎一出,所向無敵。

最引入注意的是她的 營衛組織。營衛生活不但把契丹組織、堅強

起來,更給他們一個良好的戰鬥生活。「捺鉢」是 可汗 四季漁獵

的地方,分春夏秋冬四處,因此,四季的 捺鉢 就成了 可汗 的施政

中心。

契丹的軍事組織,是全國皆兵。凡平民十五以上,五十以下,皆屬

兵役。裝備自備,人馬不發糧草。每日派兵,四處劫掠,以供軍需。

契丹軍隊分 中央軍、地方軍 與 邊防軍。契丹本系多屬宮衛或部族,

是述律皇后的一支精兵,其餘蕃漢鄉丁分屬五京,有一百一十七萬

七千餘人。她的邊防軍,分五個重點駐屯 ;以 上京 控制 諸溪,遼陽

監視 高麗,長春 壓服 東北諸國,南京 防備 趙宋,佔西京以通 西夏。

邊防設官,治理有術。對於這一點,不能不承認他們的軍事領導

能力。

契丹政治制度的特點,就是她的施政中心,不在漢人式的三京或

五京,而在契丹式的四季 捺鉢。這是 契丹游牧社會,與 中原漢唐

農業社會在政治組織的不同。「行國」與「居國」的分野。

契丹政治是番漢分治 ;番人的事務,可汗 駐嗶到那裡,就在那裡

辦公。漢人的事務,用可汗的名義委 中書省 代行,中書省 再秉告

可汗,分別追認。

契丹的世迭制度,是於部長或功臣等子孫之內,量才授與,選一人

承襲世職。完全以才能為主,沒有嫡長的限制。保功不廢庸才,父子

相繼,兄終弟及,叔姪承襲都有可能。不但可汗世迭,凡是專業,

都要世迭。

春水, 是可汗春天打獵所到的 水樂。秋山,是可汗秋天打獵所到的

山叢。他們在這裡,依照自己的傳統習俗,釣魚、捕雁、射鹿、

殺虎,置酒張晏,引抗高歌,過著痛快而可愛的生活。

在衣食住行方面,契丹人冬著貂裘、羊皮、灰鼠、沙狐,夏穿紫

窄袍,用紗冕。食以肉為主,兼食五穀,居住帳篷。契丹,男女

老幼均善騎馬。

契丹跟趙宋和好之後,因坐享巨額財貨,生活流於安逸。至 天祚帝,

昏庸荒淫,群下離心,她背後的 女真 早有取而代之的意思。

女真 入侵的時候,契丹的宗室,耶律大石 見大勢已去,率鐵騎二百

西走。破中亞回教聯軍,即稱帝位,史稱 西遼。如此又延續百年,

當 成吉思漢 時,就把她踏平了。

匈奴、突厥、契丹、蒙古,傻傻分不清楚?一文簡述草原民族源流史 - 每日頭條 (kknews.cc)

非常好听的蒙古民族歌��《Монгол эрчүүд》骏马驰骋在辽阔的草原,宁静安逸的蒙古包,成吉思汗是蒙古人心中永远的英雄! - YouTube

0 notes

Text

The Yan-yan's of Danmei

So, I read around 60 danmei titles this year, and one nickname struck me as unreasonably common for the main characters (protagonist or primary love interest): Yán-Yán, or something similar. Let's see ...

Yán-Yán 言言 version:

(言: speech, language)

卫言梓/ Wei Yanzi **, from 我磕了对家x我的cp/I Ship My Adversary an Me

祁薄言/Qi Boyan, from 诟病/Morbid Attachment

汤索言/Tang Suoyan, from 燎原/Wildfire

Yán-Yán 延延 Version:

(延: extend, prolong)

宁君延/Ning Junyan **, from 恶性依赖/Morbid Addiction

陆延/Lu Yan, from 七芒星/You are my Wonderall

顾延舟/Gu Yanzhou, from 一觉醒来听说我结婚了/ Woke up and Heard I Was Married

Other Characters or Tones:

焦炎(焦栖)/Jiao Yan aka Jiao Qi **, from 迪奥先生/Mr. Dior

钟衍 /Zhong Yan (yǎn), from 师弟还不杀我灭口/My Junior Still Hasn't Killed Me

祁晏/Qi Yan (yàn), from 论以貌取人的下场/The Consequence of Judging Others by Appearance

凌祈宴/Ling Qiyan (yàn), from 温香艳玉 (not translated? Literally: Warm, Fragrant, Bright Jade)

To be fair, I only recall three of these characters (with **) who are frequently called yanyan in-universe. Some of them are give this nickname by the author or fans.

Still, Yán, on the second tone, appeared are a main character's (or love interest's) name in around 10% of the titles, 15% if we count the other tones! Is it really a pattern or did I just stumble into an extremely biased sample?

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hunxi, you’re doing the lord’s work for promoting in the Qian Qiu fandom!!! I’m not sure if you spoke about this before, but on a personal level, why do you love Qian Qiu so much?

I don't know if I'm so much promoting 《千秋》 as I am just generally losing my mind about it on a fairly regular basis, but people continue to indulge me while I do so, so I shan't complain I've been mulling over this question for quite a while now, trying to suss out exactly why I love 《千秋》 so much, and honestly, I think the answer is just... Shen Qiao except it's never "just" "Shen Qiao," but rather Shen Qiao and his journey, Shen Qiao and the world he moves through, Shen Qiao and the intersection of themes and questions that the author investigates through his adventures, his experiences, his lowest points, his greatest heights. again, his is a character that seems simple, even two-dimensional on the surface, but the more time I spend with the text, the more his understated complexity and quiet reflections become apparent

there's a moment fairly early on in the novel that's always really stuck with me -- Shen Qiao and Yan Wushi, while entering a city, pass by a family of refugees. Shen Qiao, in a moment of soft-heartedness, hands a 饼 to one of the children, only to have the father steal it and eat it all himself, then turn around and alternately wheedle and threaten Shen Qiao for more. though we are never actually concerned for Shen Qiao's safety, the confrontation is ugly, and afterwards, Yan Wushi naturally uses the moment as another 'human nature is inherently evil' teaching lesson:

待他走近,晏无师才道:“斗米恩,担米仇。这句话,你有没有听过?” When When [Shen Qiao] came close, Yan Wushi said, " 'A handful of rice may bring gratitude, but a bushel of rice will bring enmity.' Have you heard this saying before?" 沈峤叹道:“是我鲁莽了,受苦的人很多,凭我一己之力,不可能救得完。” Shen Qiao sighed. "I acted rashly. Many people are suffering, and with only my strength, I cannot save them all." 晏无师讥讽:“人家父亲都不顾孩子死活了,你却反倒帮人家顾着孩子,沈掌教果然有大爱之心,只可惜人性、欲壑难填,无法理解你的好意,若今日你不能自保,说不定现在已经沦为肉羹了。” Yan Wushi said, mockingly, "The father didn't even care about his children's survival, yet you did. Sect Leader Shen truly has great benevolence in his heart. It's just a pity that human nature is like a vast, unfillable abyss that cannot understand your good intentions. If you couldn't protect yourself today, you might already have become meat paste." 沈峤认真想了想:“若今日我不能自保,也就不会选择走这条路,宁可绕远一点,也会避开有流民的地方。人性趋利避害,我并非圣人,也不例外,只是看见有人受苦,心中不忍罢了。” Shen Qiao diligently thought about this. "If I couldn't protect myself, I wouldn't have chosen to take this road. I would have rather walked farther around to avoid a place with refugees. Human nature naturally pursues benefit and avoids harm. I'm no saintly sage, and I'm no different. It's just that I saw someone suffering, and couldn't bear it in my heart. That's all." 他择善固执,晏无师却相信人性本恶,两人从根源上就说不到一块去,晏无师固然可以在武力上置沈峤于死地,但哪怕是他扼住沈峤的脖子,也没法改变沈峤的想法。 He stubbornly chose goodness while Yan Wushi believed that human nature was inherently evil. From their basic premises, the two of them simply could not agree. Yan Wushi could of course use his martial ability to kill Shen Qiao, but even if he held Shen Qiao by the throat, he had no way of changing Shen Qiao's mind. (chapter 16)

this by no means the first or only time Shen Qiao interacts with refugees and beggars, people driven to the ends of their tolerance and survival, people fallen on hard times, on political crises, prey to the fickleness of fortune and the rising winds of war. and, when you look at these scenes scattered throughout the book, only a few instances of these interactions are really, truly plot-relevant

which is to say that a lot of these moments are, strictly speaking, unnecessary for the forward movement of the narrative

and this is so incredibly powerful to me, because -- my god. when was the last time a beggar was allowed to be just a beggar in a wuxia danmei novel, not a spy, or an informant, or an assassin, or a member of the 丐帮 Beggar Gang, but a beggar, with all the intersectional questions of class and caste and governance and morality? when were minor figures allowed to be just that -- minor figures, passerbys, not secretly a protagonist in disguise, or a cardboard cut-out of an extra, or purely symbolic in function, but you know, a regular chump going about their dull faux-historical peasant life? how many books have their protagonists declaring that they are doing this "for the 苍生 common people," yet never really show those people on the page, or give those people a voice? how often are the poor (in a wuxia novel, no less) allowed to be more than saintly sufferers or morally corrupt, and how often do we see a narrative where our protagonist is confronted with these questions of class and privilege repeatedly, instead of a one-time save-the-cat event that serves more to illustrate a character’s virtue than it comes to examining the actual societal issues at play? Shen Qiao's beliefs and morality are tested again and again and again throughout the novel -- in big ways, with Yan Wushi, but also in little ways, in these passing moments. Shen Qiao is the best of them all -- the kindest, most benevolent, most compassionate, most forgiving -- and even he chooses, on occasion, not to help, not to give everything of himself when demanded earlier in that scene, the man asks Shen Qiao for more food, and Shen Qiao refuses. I gave you one 饼, Shen Qiao says, I only have one other, and I need to keep that for myself. we might expect a protagonist as good, as benevolent, as compassionate, as merciful as Shen Qiao to immediately cave and give up everything he has to help ease someone else’s suffering, but he doesn't. Shen Qiao is the best of all of us, and his actions show us that generosity does not have to be unlimited to be valuable, that goodness is not necessarily measured by the extremity of self-sacrifice I'm not trying to say that 《千秋》 is an insightful commentary on historical class dynamics (it’s... not), or that it handles issues with exceptional sensitivity and nuance (jury’s out on this one). but it's little moments like these in the novel that make the world feel more real, its characters more firmly grounded. the Big Questions in 《千秋》 are concerned with morality and conduct, personal cultivation and social responsibility, what it means to be a good person in a world on fire, when you yourself have been deeply wronged by the world and the people/systems of power in it. and what I find incredibly compelling is the fact that Meng Xishi devotes ink and time to both the heightened, fictional, dramatically extreme variants of these questions as well as the minute, pedestrian, and uncomfortably real the world of 《千秋》 rejects the simple binary of good and evil; it also rejects a simplistic view of what constitutes good or evil. good is more than charity, or forgiveness, or self-sacrifice, or brandishing a sword in the name of the "common people." likewise, evil cannot be reduced to just selfishness, self-interest, sadistic cruelty, or ambition. "good' and "evil" are labels, tacked onto you by loose tongues and jianghu gossip; "good" and "evil" are excuses, indiscriminately weaponized by people furthering their own agendas; "good" and "evil" are performative, external, empty; flattery, slander, meaningless

sometimes you fight to the best of your ability but your body cannot withstand the stress, and you end up coughing up blood and fainting. that is okay. sometimes someone repays your kindness by stabbing you in the back. that is okay. sometimes you have resentful, vengeful thoughts about other people who have wronged you and consider acting upon them. that is okay. sometimes you try your best to save a sickly child, and fail. the child dies in your arms. that is okay. sometimes you find out that your best intentions in the past were in fact short-sighted and selfish. that is okay. sometimes you come face to face with your own privilege, of a happy childhood, of naturally endowed martial talent, of education and access and health and ability. that is okay. sometimes you do everything in your power to try and become friends with someone, only to have them sell you out in the most viciously vindictive manner possible. that is okay.

goodness in 《千秋》 is no guarantee of reward; kindness to others has no guarantee of repayment. especially in the first third of the novel, it often feels like no good deed goes unpunished as events continue to backfire in Shen Qiao’s face. through Shen Qiao and the absolute hell he gets put through in the first half of the novel, Meng Xishi hammers this home: it isn’t easy to be good. in fact, it can be profoundly unrewarding, exhausting, even laughably naive when it would be so easy to... abridge certain morals. take a shortcut. make an exception here. everyone is just trying to survive in a world on fire, and noble words about virtue and conduct pale in the face of desperation and need

I keep thinking of this exchange, from when Shen Qiao decides to go back to save Yan Wushi:

十五:“您将他当作朋友,他不应该也将您当作朋友吗?”

Shi Wu: “You treated him like a friend; shouldn’t he also treat you like a friend?”

沈峤笑了:“不对。这世上,有许多事情,即便付出了,也很可能根本不会有回报,你在付出的时候,要先明白这一点,否则受伤的只会是你自己。”

Shen Qiao smiled. “You’re wrong. In this world, there are many things that, when you’ve paid for it, you cannot expect any sort of return. When you pay for it, you have to understand this, or else the only one who will be hurt will be you.”

(chapter 52)

I think we get a lot of stories about the radical power of empathy and forgiveness, narratives where a character’s heart and sheer goodness become something of a superpower, absolutely critical to the resolution of the conflict and the closure of the story. and those stories are some of my favorites, especially when they recognize that forgiveness is more than just a saintly forbearance, but also a negotiation of your own emotion, a necessary step towards your own closure

but kindness or compassion or empathy or goodness aren’t single, one-time events. they’re continuous and exhausting, like trying to fill up an abyss with a toy shovel. they’re often unrewarding, or invisible, or misinterpreted, or just plain go awry. 《千秋》 gives us so many iterations where characters’ good intentions rebound in their faces, or result in misfortune, and the narrative pushes past this to show us the value in continuing to make these decisions in defiance of our past experiences

or, in other words: kindness and compassion have no guarantee of reward or repayment, but that doesn’t make them any less valuable, and honestly, as someone who grew up on fantasy and the intoxicating cocktail of heroism and morality and happy endings that it often promises, 《千秋》’s understated realism and complex take on the personal cost of goodness was a story I haven’t really seen told, and didn’t know I desperately needed

#hunxi thinks about qq#(cups hands and yells into the abyss) Shen Qiao I love yooooooou#I'm not sure this post began or ended anywhere but it needs to leave so -- yeET

105 notes

·

View notes