#èṣù

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Èṣù - The gate keeper owner of all the keys, knower of all the secret things, big and small at the same time young and old. The darkness before light emerges. The trickster tricking the deserving into righteousness and tricking those who do not into calamity. The balance in all things in existence. Owner of the red and black sheild who threw a rock today and killed a bird yesterday.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oníbodè. Art by Hannah Ebunoluwa Morenikeji Bello, from Ìwà Pẹ̀lẹ́ Tarot.

Èṣù laalu ògiri oko Ọọ̀ni Ọnà Láaróyè adíjàálẹ̀ takété Onílé oríta akáṣọlórí Abániwọ́ràn-bá-ò-rí-dá A sọ ẹ̀bi dàre A sọ àre dẹ̀bi Má sọ bẹ́ẹ̀ni mi di bẹ́ẹ̀kọ́ Má sọ bẹ́ẹ̀kọ́ mi di bẹ́ẹ̀ni Èṣù má ṣe mí Èṣù dákun má ṣe mí.

#Hannah Ebunoluwa Morenikeji Bello#Ìwà Pẹ̀lẹ́ Tarot#Justice#Major Arcana#Tarot#Yoruba#Racial Diversity

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ESU-ELEGBARA COLLECTIVE

How Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára pertains to “The Spirit at the Crossroads”, and possibly Hoodoo Saint Peter

THE “ESU-ELEGBARA COLLECTIVE”

Across the African diaspora, there exists a collection of “trickster” deities, including Esu, Legba, Elegua, and their many derivatives. While these deities are different from each other, they can be grouped together because of their common origin in Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára.

Just as the Romans borrowed from the Greek pantheon, the kingdom of Dahomey borrowed from the Yoruba pantheon. The orisa and vodún were transmitted to the New World via the transatlantic slave trade, where they continued to undergo transformations.

When the Yoruba orisa Esu (Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára) was transmitted to the kingdom of Dahomey, he became the vodún Legba. When the vodún Legba was transmitted to Haiti, he refracted into the lwa Papa Legba and Mèt Kafou. When he was transmitted to Cuba, he became Elegua and Lucero Mundo.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. proposed the concept of an “Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective” in The Signifying Monkey (1988):

"Of the music, myths, and forms of performance that the African brought to the Western Hemisphere, I wish to discuss one specific trickster figure that recurs with startling frequency in black mythology in Africa, the Caribbean, and South America... This topos that recurs throughout black oral narrative traditions and contains a primal scene of instruction for the act of interpretation is that of the divine trickster figure of Yoruba mythology, Esu-Elegbara. This curious figure is called Esu-Elegbara in Nigeria and Legba among the Fon in Benin. His New World figurations include Exú in Brazil, Echu-Elegua in Cuba, Papa Legba…in the pantheon of the loa of Vaudou of Haiti, and Papa La Bas in the loa of Hoodoo in the United States. Because I see these individual tricksters as related parts of a larger, unified figure, I shall refer to them collectively as Esu, or as Esu-Elegbara. These variations on Esu-Elegbara speak eloquently of an unbroken arc of metaphysical presupposition and a pattern of figuration shared through time and space among certain black cultures in West Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and the United States. These trickster figures, all aspects or topoi of Esu, are fundamental, divine terms of mediation: as tricksters they are mediators, and their mediations are tricks. If the Dixie Pike leads straight to Guinea, then Esu-Elegbara presides over its liminal crossroads, a sensory threshold barely perceptible without access to the vernacular, a word taken from the Latin vernaculus ("native"), taken in turn from verna ("slave born in his master's house").”

SOURCE: Gates, Henry Louis. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. United States, Oxford University Press, USA, 1988. p. 5 https://archive.org/details/signifyingmonkey0000gate/page/5/mode/2up

Several other deities can considered “parts” of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective, including Lucero Mundo and Mèt Kafou (Maitre Carrefour).

While they may differ in appearance, mythology, and worship, the “parts” of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective have several things in common, including:

They are divine “tricksters”.

They are associated with a person’s fortune / fate.

They are associated with liminality and intermediary spaces (e.g., doors, gates, entrances, roads, intersections, crossroads…)

They are associated with an African understanding of the cross.

They feature prominently in their respective pantheons.

Above all, they share a common origin in Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára.

For a lengthier discussion of this concept, see: Cosentino, Donald. “Who Is That Fellow in the Many-Colored Cap? Transformations of Eshu in Old and New World Mythologies.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 100, no. 397, 1987, pp. 261–75. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/540323. Accessed 10 Sept. 2024.

2. THERE IS MORE THAN ONE HOODOO “SPIRIT AT THE CROSSROADS”

In Hoodoo, there is an unnamed “Spirit at the Crossroads” who might be connected to the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective. This spirit appears in Volumes 1 and 5 of Harry Middleton Hyatt’s Hoodoo, Conjuration, Witchcraft & Rootwork, where is called “the Devil”:

Hyatt, Hyatt, Harry Middleton. Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork, Vol. 1. United States, Western Publishing Company, 1970, pp. 97-111. https://archive.org/details/harry-middleton-hyatt-hoodoo-conjuration-witchcraft-rootwork-vols-1-5/HARRY%20MIDDLETON%20HYATT%20-%20Hoodoo%2C%20Conjuration%2C%20Witchcraft%20%26%20Rootwork%20Vo%201/page/97/mode/2up?

Hyatt, Hyatt, Harry Middleton. Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork, Vol. 5. United States, Western Publishing Company, 1978, pp. 4003-4013. https://archive.org/details/harry-middleton-hyatt-hoodoo-conjuration-witchcraft-rootwork-vols-1-5/HARRY%20MIDDLETON%20HYATT%20-%20Hoodoo%2C%20Conjuration%2C%20Witchcraft%20%26%20Rootwork%20Vo%205/page/4002/mode/2up?

An insightful video was posted on Youtube last year, titled “The Man of The Crossroads ( An Intellectual Debate) (Hoodoo)”. In this video, PapaSeer and Chan “The Musical Mystic” debate the identity of “Man at the Crossroads”.

The entire video is worth watching, and several interesting things come out of it.

At 5:17, Chan describes the crossroads spirit as “an intermediary spirit that governs the portals between the physical and spiritual”. He is associated with “keys” “windows” “doors” and “intersections”. Chan also notes that many spirits of the crossroads are considered “tricksters” , where lengthier discussions of trickster spirits take place at 36:45 and 51:28.

At 26:13, PapaSeer provides a detailed description of the “Man at the Crossroads”, who is figured as a “Dealmaker”:

“The man at the Crossroads, when he materializes, is typically – from what I’ve always seen – it’s always been in the form of some type of beggar. And it’s not always a Black person… It’s always some type of beggar… somebody that needs something. The man at the Crossroads tends to favor people who are downtrodden, who are in a very bad situation, when your luck is not lucky, when you are just at your wits end, this is when he tends to show some favor to people. Now, outside of that, he want what he wants to give you something back. And I haven’t seen anything outside of that. So when people talk about he’s a spirit of protection, and this, and that, I’m just like ‘No, he’s simple! He want something to give you back something!’ And you have to make some type of pact. You have to form some type of deal for this relationship to flourish. You can’t even just come to him just one time. It’s a succession of times that you have to petition him for it to be effective. This has been my personal experience.”

At 46:01 and 48:46, PapaSeer and Chan both describe the physical appearance of the Spirit at the Crossroads. He is described as a humble, old beggar, who wears tattered clothes and has no interest in material things.

Importantly, PapaSeer and Chan agree that the Spirit at the Crossroads is more than one thing. They assert that he can manifest as several different deities, including Jesus (Yeshua) and the Christian Devil.

Notably, both debaters of the Abrahamic Hoodoo tradition. PapaSeer is from Virginia, while Chan is from South Carolina – closer, in proximity, to New Orleans. Folklore involving the Spirit at the Crossroads is described as being “very prevalent” in the Deep South. It is not PapaSeer, but Chan who identifies the Crossroads Spirit with certain African-derived deities - namely, Esu, Elegua, and Legba.

If this Spirit at the Crossroads is a part of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective, which one(s) could he be?

3. SIMILARITIES WITH ESU

What is arguably the single most fascinating trickster god from any world religion, Esu (Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára) is a deity whose complexity is often compressed and mischaracterized.

A being with many different names and forms, Ayodele Ogundipẹ describes Esu like so:

“Èṣù…is the messenger of the gods, the mediator between God and humans between order and chaos, sin and punishment, life and death, fate and accident, certainty and uncertainty. It is no wonder then, that Èṣù in myth knows no master, that he is male and female, that he is tall and short, kind and cruel, an elderly deity of youth who lives at the crossroads.”

SOURCE: Ogundipe, Ayodele. Esu Elegbara: chance, uncertainty in Yorùbá mythology. Kwara State University Press, 2018. p. 130

Funso Aiyejina describes Esu as “the deity of choice and free will”. His behavior reflects the nature of fate itself - unpredictable. His tricks and mischief often serve the purpose of teaching lessons; especially, that one requires complete information and consciousness before exercising judgment.

SEE: Oyèláràn, Ọlásopé O. "Èṣù and ethics in the Yorùbá world view." Africa 90.2 (2020): 377-407.

Esu is also called onile orita or “the one who lives at the crossroads”, for that is where he dwells. While it is often translated as “crossroads”, the word orita refers to several different types of intermediary spaces, including front yards and gateways. For this reason, Esu is described as both “gatekeeper” and “lord of crossroads”, where the orita symbolizes the intersection of physical and metaphysical realms in Yoruba philosophy.

SEE: Aiyejina, Funso. "Esu Elegbara: A Source of an Alter/Native Theory of African Literature and Criticism." text of a lecture from his work in progress on ‘Decolonising Myth: From Esu to Bachaanal Aesthetics (2010). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=25a632183b18b3d34abea946fb0fab4e0f6a864f

While he is often figured as being small and dark-skinned, Esu is a shape-shifter who can assume hundreds of different forms. One of the forms Esu assumes is that of an “old man at the crossroads”. In this form, he smokes a pipe:

“My informants told me that Èṣù’s pipe accouterments are for his depiction as an old man or an elder, for the elderly in Yoruba society like to relax with a pipe. My informants also told me that since Èṣù lives at the crossroads and in open places, one way people know he is there, especially after dark, is by smoke puffs from his pipe. Seeing the glow from the pipe, passersby would salute him, ‘Epa Èṣù!’”

SOURCE: Ogundipe, Ayodele. Esu Elegbara: chance, uncertainty in Yorùbá mythology. Kwara State University Press, 2018. p. 98

This is similar to how Hyatt’s “Devil at the Crossroads” manifests in different forms, ranging from a “great big black man” to a "a lil' ole funny boy”

Ogundipe describes Esu as energetic and loving to dance (p. 64), while Gates describes him as limping (p. 6):

"In Yoruba mythology, Esu is said to limp as he walks precisely because of his mediating function: his legs are of different lengths because he keeps one anchored in the realm of the gods while the other rests in this, our human world."

SOURCE: Gates, Henry Louis. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. United States, Oxford University Press, USA, 1988. p. 6 https://archive.org/details/signifyingmonkey0000gate/page/6/mode/2up?

4. SIMILARITIES WITH PAPA LEBAT (NEW ORLEANS VOODOO)

It is important to note that there are three different deities named Legba:

Legba of West African Vodún

Papa Legba of Haitian Vodou

Papa Lébat (“Papa La Bas”) of New Orleans Voodoo (Louisiana Voudou)

The most popular name for Papa Lébat was probably “Papa La Bas” or “La Bas” (“Laba”). However, I avoid calling him this, as it is a reference to “Satan”. He was called other names, like "Papa Limba". In the present day, neither “Papa Lébat” nor "Papa La Bas" is commonly used; he is usually just called "Papa Legba", which is actually the accurate pronunciation. So not to confuse him with the West African vodún or the Haitian lwa, I will refer to the spirit of New Orleans Voodoo as “Papa Lébat”.

Much like the different parts of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective, these should be considered different deities who are worshiped in different ways.

As the Romans borrowed Hermes from the Greeks, the Fon borrowed Esu from the Yoruba. In the kingdom of Dahomey, Esu became Legba.

There are many similarities between Esu and Legba, as described by Steven M. Friedson:

“A divine trickster, Legba, as with that other phallic god Hermes, is also the divine messenger, the linguist (tsiami) who speaks the language of the sky. Because he patrols the borders and protects the threshold, all sacrifice, all libation, ultimately all meaning goes and comes through him, hence his infinite possibilities, his refusal to be pinned down. Translator, trickster, protector, linguist–all this and more comes under the sign of the crossroads where Legba rules, where there are always-already multiple paths, multiple meanings. And lest we think we have finally pinned Legba down as the phallic god par excellence, pregnant with meaning, it is helpful to remember that sometimes, though it is fairly rare, Legba manifests himself in female form complete with clay breasts. Nothing is quite what it seems.”

SEE: Friedson, Steven M. Remains of ritual: Northern gods in a southern land. University of Chicago Press, 2019. https://staff.washington.edu/ellingsn/Friedson-Remains-Ritual_00_Title-Intro.pdf

AND: Ogundipe, Ayodele. Esu Elegbara: chance, uncertainty in Yorùbá mythology. Kwara State University Press, 2018. pp. 120-123

Like Esu, Legba presides over crossroads and gates:

“The assistants knelt in front of a large white basin around which a circle of chalk was inscribed in the sand for Legba, Yewevodu god of crossroads, keeper of gates, and guardian of ritual knowledge.”

SOURCE: Montgomery, Eric, and Vannier, Christian. An Ethnography of a Vodu Shrine in Southern Togo: Of Spirit, Slave and Sea. Netherlands, Brill, 2017. p. 197

Unlike Esu, the vodún Legba is associated with the dog - “the animal is sacred to him”. He also has a different origin myth from Esu, where he was made chief of the gods for his mastery over musical instruments. For this reason, he is associated with music and dancing.

SOURCE: Herskovits, Melville Jean, and Frances Shapiro Herskovits. Dahomean narrative: a cross-cultural analysis. Northwestern University Press, 1958. https://archive.org/details/dahomeannarrativ0000hers/page/138/mode/2up?

Notably, “The Devil at the Crossroads” is also associated with music, where a section of Hoodoo - Conjuration - Witchcraft - Rootwork, Vol. 1 is titled “Diabolic Music”. For a lengthier discussion about this shared connection, see: Marvin, Thomas F. “Children of Legba: Musicians at the Crossroads in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” American Literature, vol. 68, no. 3, 1996, pp. 587–608. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928245. Accessed 11 Sept. 2024.

“The Spirit at the Crossroads” might also have an association with dogs. Dogs also appear a few times under Hyatt’s “Sell Self to the Devil”, with one of the most memorable accounts involving "a lil' ole funny boy” – described as a strange dog/human hybrid. In another case, a man goes to the crossroads to acquire musical talent, but is scared off by a big black dog. Because he is associated with other animals, it is unclear whether the Crossroads Spirit has a fondness for dogs, or if it is a mere coincidence.

In Haiti, Legba underwent a dramatic transformation. Where the Dahomean Legba appeared as a hypersexual young man, the Haitian Papa Legba appears as a weary, old man.

Milo Marcelin described Papa Legba him like so:

“On se le représente sous les traits d'un vieillard, cassé par l'âge, à demi paralysé, qui s'avance péniblement avec l'aide d'une canne ou d'une béquille. Le nom de Legba-pied-cassé, qui lui est parfois donné, traduit bien l'aspect pitoyable sous lequel on se l'imagine. Legba est coiffé d'un chapeau de paille à large bord, il porte une macoutte (sacoche en feuilles de latanier) et i fume sans arrêt une longue pipe en terre cuite. Son grand chapeau lui permet de protéger les loa de Guinée (d'Afrique) contre les ardeurs du soleil…”

TRANSLATION:

“He is represented as an old man, broken by age, half-paralyzed, who hobbles with the aid of a cane or crutch. The name Legba-pied-cassé, which is sometimes given to him, translates well the pitiful appearance in which he is imagined. Legba dons a large-brimmed straw hat, he carries a macoutte (palm leaf sack) and he endlessly smokes a long, terracotta pipe. His large hat lets him protect the loa from Guinea (Africa) from the heat of the sun…”

SOURCE: MARCELIN, Émile, and A. Métraux. “LES GRANDS DIEUX DU VODOU HAIÏTIEN.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes, vol. 36, 1947, pp. 51–135. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24601899. Accessed 18 Sept. 2024.

Interestingly, Papa Legba appears similar to the form Esu assumes when disguising himself as an old man, where both smoke a pipe. Like his Fon counterpart, Papa Legba is associated with dogs and described as a “trickster”.

In the present day, Papa Legba is often associated with gates and doors, while the Petwo lwa Mèt Kafou (Maitre Carrefour) is associated with crossroads. However, this distinction does not seem to have always been the case.

Marcelin described Papa Legba as a lwa with many names and functions, where he is both doorkeeper and “master of crossroads”:

“Papa Legba ou Atibon-Legba est le dieu des portes, le maître des carrefours et des croisées de chemins et le protecteur des maisons. En vertu de ces différentes fonctions, il est invoqué sous les noms de « Legba-nan- bayè » (Legba des barrières), de « Legba-calfou » (Legba des carrefours) ou « Grand chemin », de « Legba Mait' bitation » ou « Legba Maiť habitation ». En tant que dieu qui sait toutes choses, il porte l'épithète d'Avadra...”

“...Pour invoquer Legba, l'officiant se sert d'une pierre qu'il place sur l'autel. Ensuite il trace un dessin symbolique (vèvè) sur le sol et récite la prière suivante :

Par pouvoir saint Antoine, au nom de M. Avadra Boroy, de Legba-Atibon, le maître des carrefours et des grands chemins, de Legba-Kataroulo, de vaillant Legba, de Legba-Sé, de Alegba-Si, de Legba-Bois, de Legba-Zinchent, de Legba- Caye, de Legba-Misé-ba, de Legba-Clairondé, de Legba-Signangnon, des sept Legba-Kataroulo, vieux, vieux, vieux Legba. Ago, Agoé, Angola.”

TRANSLATION

“Papa Legba or Atibon-Legba is the god of doors, the master of crossroads and the protector of houses. By virtue of these different functions, he is invoke under the names of “Legba-nan- bayè” (Legba of the Barriers), “Legba-calfou” (Legba of the Crossroads) or “Grand chemin”, “Legba Mait’ bitation” or “Legba Mait’ habitation”. As the god who knows all things, he bears the epithet of “Avadra”...”

“...To invoke Legba, the officiant uses a stone that he places on the altar. Then he traces a symbolic drawing (vèvè) on the ground and recites the following prayer:

By the power of Saint Anthony, in the name of Mr. Avadra Boroy, of Legba-Atibon, the master of the crossroads and great paths, of Legba-Kataroulo, of valiant Legba, of Legba-Sé, of Alegba-Si, of Legba-Bois, of Legba-Zinchent, of Legba-Caye, of Legba-Misé-ba, of Legba-Clairondé, of Legba-Signangnon, of the seven Legba-Kataroulo, old, old, old Legba. Ago, Agoé, Angola.”

SOURCE: MARCELIN, Émile, and A. Métraux. “LES GRANDS DIEUX DU VODOU HAIÏTIEN.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes, vol. 36, 1947, pp. 51–135. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24601899. Accessed 18 Sept. 2024.

This might explain why New Orleanians - such as Ava Kay Jones and Denise Alvarado - have described Papa Lébat (“Papa La Bas”) as both gatekeeper and guardian of the crossroads. Although I have been referring to it as “New Orleans Voodoo”, this is a misnomer, as the religion was practiced across the Mississippi River Valley of America. New Orleans Voodoo is not Americanized Haitian Vodou, but has a rich history that predates the Haitian migration wave. That being said, several Haitian elements can be identified.

Following the Haitian Revolution, a large number of Haitians fled to the city of New Orleans. With them, they brought their religious practices, which were incorporated into the Voodoo (Voudou) that was already present in America. As there is continuity between Fon Legba and Haitian Papa Legba, there is also continuity between the Haitian Papa Legba and the American Papa Lébat.

Much like his Haitian counterpart, Papa Lébat was identified with St. Peter, and a similar song was sung asking him to “open the door” (“ouvre baye”):

“Marie Laveau…even taught her a Voodoo song. It went like this:

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door,

I’m callin’ you, come to me!

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door …

“That’s all I can remember. Marie Laveau used to call St. Peter somethin’ like ‘Laba.’ She called St. Michael ‘Daniel Blanc,’ and St. Anthony ‘Yon Sue.’”

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983.

The historical record of Papa Lébat is sparse, but it is likely that there were differences between him and Papa Legba. For one, there were already people of Fon/Ewe descent in America, who may have been worshiping the vodún Legba prior to the Haitian migration wave. For two, there is no record of an American version of Maitre Carrefour. In the historical record, it is not Maitre Carrefour, but “Papa La Bas” who is identified with “The Devil”.

For these reasons, it is not the Haitian lwa, but the American Papa Lébat who might be identified with “The Devil at the Crossroads”.

5. SIMILARITIES WITH MAITRE CARREFOUR

It is presently unknown whether Maitre Carrefour was worshiped in New Orleans, or if the division between Papa Legba and Maitre Carrefour existed there. Since he is one of the Petwo lwa, it is possible that he was worshiped in secret. If so, he would have been brought to New Orleans by followers of the Don Pedro sect - the colonial precursor to the Petwo rite.

Similar to Esu and Legba, Maitre Carrefour is sometimes erroneously described as “evil” or a “demon”.

In Vol. 1 of Hyatt’s Hoodoo Conjuration Witchcraft & Rootwork (5 vol.s), there is a subsection of “SELL SELF TO THE DEVIL”, titled “BIG BLACK MAN”. In one of these interviews, “The Devil” is described as “a great big black man”. In another, he is described as “a big black man” who gives you “the power to accomplish what you want to do.”

Source: “BIG BLACK MAN” under “SELL SELF TO THE DEVIL”, in Hyatt, Harry M. "Hoodoo; Conjuration; Witchcraft; Rootwork (5 Volumes)." Hannibal, MO: Western Publishing Company (Vol. 1) (1970). pp. 103-104: https://archive.org/details/HoodooConjurationWItchcraftRootwork/Hoodoo%20Conjuration%20WItchcraft%20%26%20Rootwork%20Vol%201/page/n167/mode/2up

Tommy Johnson (unrelated to Robert Johnson) made a similar comment, as quoted by his brother Rev. LeDell Johnson:

“Take your guitar and you go down to where a road crosses that way, where a crossroad is. Get there, be sure to get there just a little ‘fore twelve o’clock that night so you know you’ll be there. You have your guitar and be playing a piece sitting there by yourself. You have to go by yourself and be sitting there playing a piece. A big black man will walk up there and take your guitar, and he’ll tune it. And he’ll play a piece and hand it back to you. That’s the way I learned how to play anything I want.” Source: Evans, David (1971 ). Tommy Johnson. Studio Vista, London p. 22-23. ISBN978-0289701515.

This is similar to Maya Deren’s description of Maitre Carrefour:

“This is no ancient, feeble man; Carrefour is huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life. His arms are raised strongly in the configuration of a cross. Every muscle of the shoulders and back bulges with strength. No one whispers or smiles in his presence.”

Source: Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 101: https://archive.org/details/divinehorsemenli00dere/page/100/mode/2up

Maitre Carrefour’s colors are red and black, which might be relevant if “The Spirit at the Crossroads” also wears these colors.

In part, the Petwo rite has been misrepresented as “evil” because of the threat it posed to the institution of slavery, with its founder Don Pedro (Jean Petro) being a maroon leader. Lwa within the Petwo rite can grant someone immediate access to power without regard for systems of morality. Naturally, such immediate access to power would be dangerous and easily abused, but it can also be used for just causes, such as the liberation of slaves.

From Maya Deren:

"If the Rada loa represent the protective, guardian powers, the Petro loa are the patrons of aggressive action….For example, whereas Erzulie, the Rada Goddess of Love, who is the epitome of the feminine principle, is concerned with love, beauty, flowers, jewelry, femininities and coquetries, liking to dance and to be dressed in fine clothes, weeping in a most feminine fashion for not being loved enough, the figure of Erzulie Ge/Rouge, on the Petro side, is awesome in her poignancy. When she possesses a person, her entire body contracts into the terrible paralysis of frustration; every muscle is tense, the knees are drawn up, the fists are clenched so tightly that the fingernails draw blood from the palms. The neck is rigid and the tears stream from the tightly shut eyes, while through the locked jaw and the grinding teeth there issues a sound that is half groan, half scream, the inarticulate song of in/turned cosmic rage.Petro was born out of this rage. It is not evil; it is the rage against the evil fate which the African suffered, the brutality of his displacement and his enslavement. It is the violence that rose out of that rage, to protest against it. It is the crack of the slave/whip sounding constantly, a never-to-be-forgotten ghost, in the Petro rites. It is the raging revolt of the slaves against the Napoleonic forces. And it is the delirium of their triumph. For it was the Petro cult, born in the hills, nurtured in secret, which gave both the moral force and the actual organization to the escaped slaves who plotted and trained, swooped down upon the plantations and led the rest of the slaves in the revolt that, by 1804, had made of Haiti the second free colony in the western hemisphere, following the United States. Even today the songs of revolt, of "Vive la liberte", occur in Petro ritual as a dominant theme.”

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. United States, McPherson, 1983. pp. 61-62 https://archive.org/details/divinehorsemenli00dere/page/60/mode/2up?

For this reason, Hoodoo has been likened to the Petwo rite - not the Rada rite - of Haitian Vodou:

“The Petwo side of Vodou is one largely of action; it can be said that it is the Petwo incarnation of Vodou that is recognizable in American Hoodoo Conjure.”

Lane, Megan. Hoodoo heritage: A brief history of american folk religion. Diss. University of Georgia, 2008. https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/lane_megan_e_200805_ma.pdf

If Maitre Carrefour had already split off from Papa Legba, maybe he was incorporated into the Hoodoo community, where he was identified with “The Devil at the Crossroads”.

6. THE CROSSROADS SPIRIT - A NOVEL ASPECT OF ESU-ELEGBARA?

Rather than being Esu, Papa Lébat, or Maitre Carrefour, “The Spirit at the Crossroads” might be a novel aspect of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective.

Every time Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára is transmitted to a new culture, he undergoes transformations. Furthermore, African Americans of the South are ethnically heterogeneous, where some descend from the Yoruba, the Fon, the Ewe, and so on. Historically, Esu and Papa Lébat were both identified with Satan. Over time, African Americans forgot the names Esu and Lébat. He was simply called “the Devil”; later, “The Spirit at the Crossroads”.

Because they were both identified with “The Devil” and “crossroads”, it is plausible that Esu and Papa Lébat recombined with each other, forming a new part of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective. This could explain why “The Spirit at the Crossroads” shares traits with Esu and Papa Lébat.

7. ESU-ELEGBARA, THE DEVIL, & JESUS CHRIST

It may be worth noting that parts of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective are paradoxically associated with both the Devil and Jesus Christ.

Historically, he was not called “Spirit” but “The Devil at the Crossroads” (see: Harry Middleton Hyatt’s Hoodoo, Conjuration, Witchcraft & Rootwork, Vol. 1 & Vol. 5)

Esu was associated with the Devil, to the extent that the word “Devil” was translated as “Esu” in the Yoruba language. See: Kanu, Ikechukwu Anthony. "The hellenization of African traditional deities: The case of Ekwensu and Esu." AQUINO| Journal of Philosophy 1.3 (2021). https://acjol.org/index.php/aquino/article/download/1830/1808

In Dahomean Narrative (1958), Herskovits describes how the vodún Legba was identified with the Devil: "It has been conjectured that the Christian missions, by identifying Legba with the Devil, have helped to make him an especially popular figure in Dahomean lore." p. 36

In America, Papa Lébat (“Papa La Bas”, “Papa Limba”) was identified with the Devil by interviewees of the Federal Writer’s Project, which can be found in Robert Tallant’s (1984) Voodoo in New Orleans.

One of these interviews involves Alexander Augustin, described by Noël Mellick Voltz as a “former free person of color”, “an old mulatto”, and a “spiritualist”:

“Alexander Augustin remembered some of the tales of old people which dated to the era of the Widow Paris.

They would thank St. John for not meddlin’ wit’ the powers the devil gave ’em,” he said. “They had one funny way of doin’ this when they all stood up to their knees in the water and threw food in the middle of ’em. You see, they always stood in a big circle. Then they would hold hands and sing. The food was for Papa La Bas, who was the devil. Oldtime Voodoos always talked about Papa La Bas. I heard lots about the Maison Blanche. It was painted white and was built right near the water wit’ bushes all around it so nobody couldn’t see it from the road. It was a kind of hoodoo headquarters.”

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. pp. 65-66

A second interview involves Josephine McDuffy (“Josephine Green”), described by Jeffrey E. Anderson as a “former slave”:

Josephine Green, an octogenarian, recalled her mother’s stories about Marie Laveau.

“My ma seen her,” Josephine boasted. “It was back before the war what they had here wit’ the Northerners. My ma heard a noise on Frenchman Street where she lived at and she start to go outside. Her pa say, ‘Where you goin’? Stay in the house!’ She say, ‘Marie Laveau is comin’ and I gotta see her.’ She went outside and here come Marie Laveau wit’ a big crowd of people followin’ her. My ma say that woman used to strut like she owned the city, and she was tall and good-lookin’ and wore her hair hangin’ down her back. She looked just like a Indian or one of them gypsy ladies. She wore big full skirts and lots of jewelry hangin’ all over her. All the people wit’ her was hollerin’ and screamin’, ‘We is goin’ to see Papa Limba! We is goin’ to see Papa Limba!’ My grandpa go runnin’ after my ma then, yellin’ at her, ‘You come on in here, Eunice! Don’t you know Papa Limba is the devil?’ But after that my ma find out Papa Limba meant St. Peter, and her pa was jest foolin’ her.”

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. Pp. 57-58

This is probably why the most popular name for Papa Lébat is “Papa La Bas”, “La Bas”, or “Laba”. “La Bas” used to mean “Down There”, and was associated with Satanism, while “Laba” is the Creole form of “La Bas”.

Ironically, the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective is also associated with Jesus Christ, for two reasons:

Both are both figured as connection points between humanity and the divine.

They have a common association with the cross symbol.

In African religious systems, the cross is a cosmographic symbol. It represents the intersection of the spiritual and mortal realms, which are figured as two perpendicular planes.

A complete discussion of this concept can be found here:

Desmangles, Leslie Gerald. “African Interpretations of the Christian Cross in Vodun.” Sociological Analysis, vol. 38, no. 1, 1977, pp. 13–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3709833. Accessed 10 Sept. 2024.

Pictured: Papa Legba’s vèvè

This explains why Papa Legba’s vèvè features a prominent 4-point cross, and why parts of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective are associated with Jesus. For example, the Haitian author Milo Rigaud identified Legba as “the Voodoo Jesus”, while Eleguá is syncretized with the Child Jesus of Atocha.

It might also relate to why Chan, who is from deeper South, differentiates forks in the road from crossroads. Here, he stresses the importance of the crossroads as a “cross”. The crossroads are figured as having “four specific points”, while forks do not. PapaSeer, who is from further north, disputes the importance of the “four specific points”. He argues that forks and crossroads are the same, in that they are both points of intersection between the spiritual and physical realms.

The parts of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective are characterized by their extreme unpredictability, where they are capable of Christ-like benevolence and devilish malevolence. This reflects the unpredictable nature of a person’s fate, and the liminal space between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. For this reason, it is possible that different aspects of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective can manifest as “The Spirit at the Crossroads”.

On the off chance that someone from the Abrahamic Hoodoo tradition is reading this, I do not mean that Jesus does not appear at the Crossroads, or that Jesus and Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára are the same thing. That would be equally erroneous as equating Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára with the Devil. Rather, I mean that these benevolent and malevolent aspects of Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára might also be able to manifest, alongside Jesus and the Devil. At that, it would be crucial to analyze if and how the Crossroads Spirit(s) is benevolent and/or malevolent.

8. HOODOO SAINT PETER

Hoodoo Saint Peter might also be a part of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective.

In Hoodoo, Saint Peter is figured differently from European traditions. He is associated with a person’s fate, where he is petitioned to “open” or “close” the doors to opportunities. This is a feature he shares with the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective, which is tied to a person’s fortune / fate, and associated with “doors” “keys” and “entrances”.

Here is how Legba is described in Dahomean Narrative:

“Myth (hwenoho). The long stories about Legba are particularly useful for a closer analysis of narrative. But before we turn to the stories, we must give attention to the role Legba plays in Dahomean life. As had been shown, he is a figure of the greatest importance both in the generalized form in which he participates in the worship of the vodun pantheons, and more particularly a guardian of entrances to villages, to markets, to shrines, compounds, and houses, until he is brought into the closest association of all—with a man’s personal destiny (his Fa).”

Source: Herskovits, Melville Jean, and Frances Shapiro Herskovits. Dahomean narrative: a cross-cultural analysis. Northwestern University Press, 1958. p. 36 https://archive.org/details/hersokovits-dahomean/page/35/mode/2up

In Haitian Vodou, Papa Legba was identified with Saint Anthony, but also Saint Peter:

“Legba est identifié à saint Antoine l'ermite et à saint Antoine de Padoue…Mais Legba est aussi saint Pierre qui, tout comme lui, est un portier divin.”

TRANSLATION:

"Legba is identified with Saint Anthony the Hermit and with Saint Anthony of Padua...But Legba is also Saint Peter who, just like him, is a divine doorkeeper."

SOURCE: MARCELIN, Émile, and A. Métraux. “LES GRANDS DIEUX DU VODOU HAIÏTIEN.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes, vol. 36, 1947, pp. 51–135. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24601899. Accessed 18 Sept. 2024.

In New Orleans Voodoo, Papa Lébat was associated with Saint Peter.

From the interview with Josephine McDuffy (“Josephine Green”):

Josephine Green, an octogenarian, recalled her mother’s stories about Marie Laveau.

“My ma seen her,” Josephine boasted. “It was back before the war what they had here wit’ the Northerners. My ma heard a noise on Frenchman Street where she lived at and she start to go outside. Her pa say, ‘Where you goin’? Stay in the house!’ She say, ‘Marie Laveau is comin’ and I gotta see her.’ She went outside and here come Marie Laveau wit’ a big crowd of people followin’ her. My ma say that woman used to strut like she owned the city, and she was tall and good-lookin’ and wore her hair hangin’ down her back. She looked just like a Indian or one of them gypsy ladies. She wore big full skirts and lots of jewelry hangin’ all over her. All the people wit’ her was hollerin’ and screamin’, ‘We is goin’ to see Papa Limba! We is goin’ to see Papa Limba!’ My grandpa go runnin’ after my ma then, yellin’ at her, ‘You come on in here, Eunice! Don’t you know Papa Limba is the devil?’ But after that my ma find out Papa Limba meant St. Peter, and her pa was jest foolin’ her.”

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. Pp. 57-58

From an interview with a woman named Mary Washington (“Mary Ellis”):

Mary said that most of the things she knew about Marte Laveau had been told her by an aunt who had been a Voodoo.

“My aunt told me one time she had trouble wit’ her landlord. He told her to git out of her house or he’d have her put in jail,” Mary said. “He even sent a policeman after her. The next day she went to Marie Laveau and she told my aunt to burn twelve blue candles in a barrel half full of sand. She done that and my aunt never did have to move and she never went to jail in her whole life. Marie Laveau used to tell people not to burn candles in church ’cause that gived their luck to somebody else, so they burned ’em in her house instead. She’d tell my aunt, ‘If you gonna fool ’em, fool ’em good, Alice.’ She was real good to my aunt. She even taught her a Voodoo song. It went like this:

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door,

I’m callin’ you, come to me!

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door …

“That’s all I can remember. Marie Laveau used to call St. Peter somethin’ like ‘Laba.’ She called St. Michael ‘Daniel Blanc,’ and St. Anthony ‘Yon Sue.’ There was another one she called ‘On Za Tier’; I think that was St. Paul. I never did know where them names come from. They sounded Chinee to me. You know the Chinee emperor sent her a shawl? She wore it all the time, my aunt told me.”

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983.

New Orleans Voodooists hid African-derived spirits like Papa Lébat and Daniel Blanc under the names of Catholic Saints, who were petitioned for the following reasons:

These merchants also sell pictures of saints. To certain Roman Catholic saints particular Voodoo power has been attributed: St. Michael is thought best able to aid in conquering enemies; St. Anthony de Padua is invoked for “luck”; St. Mary Magdalene is popular with women who are in love; St. Joseph (holding the Infant Jesus) is used to get a job. Many Voodoos believe a picture of the Virgin Mary in their homes will prevent illness, and that one of St. Peter (with the Key to Heaven) will bring great and speedy success in financial matters (without the Key to Heaven, St. Peter is still reliable in helping in the achievement of minor successes; the power of the picture is less, however). Pictures of the Sacred Heart of Jesus are believed to have the ability to cure organic diseases.

SOURCE: Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983.

In Hoodoo, the real identity of the being petitioned as “Saint Peter” might not be Peter the Apostle, but Papa Lébat, whose name was forgotten over time.

If this is true, it seems that Papa Lébat refracted into two different entities: Hoodoo Saint Peter, and the Hoodoo Spirit at the Crossroads. This is similar to how the vodún Legba refracted into Papa Legba and Mèt Kafou when he was transmitted to Haiti. It is unclear whether these two refractions correspond with each other, or if Hoodoo Saint Peter and The Spirit at the Crossroads should be considered novel aspects of the Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára collective.

9. CONCLUSIONS

The above are merely personal hypotheses of mine, which can readily be verified or debunked by members of the Hoodoo and Voodoo communities. I belong to neither, nor do I have any Black African heritage. It would be these two groups who contain the most accurate information about the Spirit at the Crossroads, Hoodoo Saint Peter, and Papa Lébat.

In other words, they can tell you if this is bullshit or not.

For example, they can tell you if there’s any association between the Spirit at the Crossroads and dogs, if he smokes a pipe, if he wears a hat, if so what kind, if he limps, what his colors are, etc…

Here’s another opinion no one asked for!

Americans have attempted to reconstruct Voodoo by drawing from Haitian Vodou and West African Vodun. While it is prudent to connect with Haitians and West Africans, American Voodooists should prioritize communication with members of the Hoodoo community. There are many African Americans who descend from the Haitian slaves that arrived in New Orleans following the Haitian Revolution. While there exists an ancestral tie, there is also a large, 200-year discontinuity between this migration wave and the present day. Vodou – of the Mississippi River Valley, and of Haiti – is an ancestral tradition. The one who has maintained an unbroken ancestral chain is not the Haitian lwa Papa Legba, but the Hoodoo Spirit at the Crossroads.

In the words of Albert J. Raboteau, “In the United States the gods of Africa died” ...except one! Arguably, the most important one, who “holds the keys” to the other gods…!

AND PEOPLE JUST LEAVE THEIR TRASH IN THE PLACE WHERE HE DWELLS!!!!!

HE DOESN”T EVEN HAVE A NAME!!!!!!!!

…Sorry. I’m a very sensitive person, so this upsets me.

But isn’t that interesting?

In the entire Yoruba pantheon, Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára might be the single most persistent deity!

* * *

Revisiting the origins of Kafou

Up until this point, I have been describing Kafou as a Petro-ified counterpart to Legba, categorizing him as part of Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Esu-Elegbara collective. However, such description surely understates Kafou’s Central African origins.

The Gatekeeper/Crossroads Spirits Legba and Esu are prominent features of West African religions; however, the 4-point Crossroads were also important to the Central Africans.

Pictured: Kafou’s veve

Many different veves incorporate Central African symbology into their designs. In particular, the veve of Kafou closely resembles symbols from the Congo, the most famous being the Bakongo Cosmogram.

Pictured: Bakongo Cosmogram

Rigaud also described Kafou Louvem'bha, surely derived from the word Luvemba.

SEE: Rigaud, Milo. La tradition voudoo et le voudoo haïtien: son temple, ses mystères, sa magie. FeniXX, 1953. p. 174. Retrieved from: https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/AA00002240/00001/183j

There are other ethnic groups from the Congo who also worshiped the crossroads, as the 4-point Cross(roads) is an ancient symbol that has variants in many different African cultures. Without attributing it to any particular ethnic group, the Central African influence is undeniable.

With this in mind, one of two things could be true:

Kafou is truly Creole in origin; he merges the Crossroads Symbol of Central Africa with the Gatekeeper/Crossroads Spirit of West Africa.

Kafou is simply the embodiment of the Crossroads Symbol of Central Africa; his similarity to Legba and Esu is merely superficial.

If the second is true, it would be incorrect to identify him with the Esu-Elegbara collective, and would explain why Kafou is categorized as a different famille from Legba.

While Milo Rigaud and Milo Marcelin identified Kafou with Legba, others deny this association, citing a Central African origin instead.

It was negligent of me not to have mentioned this earlier.

* * *

Revisiting this topic, I think I can debunk myself a bit.

After researching this a bit further, Hoodoo Saint Peter seems to just be Saint Peter; no connection to the West African Legba.

On the other hand, the origin of the Spirit at the Crossroads was described as “controversial”. Basically, some think a connection to Esu or Legba is possible; others deny this connection.

#commentary#EVERY NIGHT I CRY MYSELF TO SLEEP KNOWING THAT THE HOODOO SPIRIT AT THE CROSSROADS DOESN"T EVEN HAVE#A NAME!!!!!!!!!!!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Èṣù/Ellequa!: The Misunderstood Deity in Yọrùbá Religion"

Èṣù is one of the most misunderstood deities in the Yọrùbá pantheon. Often portrayed as the devil or Satan in Western media and popular culture, Èṣù is actually a complex and multifaceted deity with a rich history and important role in Yọrùbá culture and religion.

In Yọrùbá religion and mythology, Èṣù is the deity of crossroads, communication, and trickery. He is often depicted as a mischievous figure, playing pranks on humans and other deities alike. However, his role is much more nuanced than simply causing chaos and confusion.

Èṣù is seen as a mediator between the spiritual and physical worlds. He is responsible for conveying prayers and offerings to the other deities and is the messenger between the gods and humans. As the deity of communication, he is also associated with language and speech, and is often invoked during important ceremonies and rituals.

Despite his important role in Yọrùbá culture, Èṣù has been demonized and vilified in Western media. This is largely due to the influence of Christian missionaries, who saw Èṣù as a threat to their own religious beliefs and sought to discredit him by associating him with Satan.

However, this portrayal is not only inaccurate, but also harmful. By equating Èṣù with Satan, Western media perpetuates harmful stereotypes and reinforces negative attitudes towards African religions and cultures.

The portrayal of Èṣù as a demonic figure also erases the complex and multifaceted nature of Yọrùbá religion. Yọrùbá belief systems are not dualistic like Christianity, where there is a clear division between good and evil. Instead, Yọrùbá deities like Èṣù embody a range of qualities, both positive and negative, and are often seen as complex figures who can be both helpful and mischievous. By reducing Èṣù to a caricature of evil, Western media misses the nuances of Yọrùbá religion and perpetuates harmful stereotypes that can lead to discrimination and prejudice again

#afrodiaspores#spirit work#witches#ifa in usa#reading#isese#traditional#astrology#traditional witchcraft#ifa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Èṣù is an Òrìṣà/Irúnmọlẹ̀ in the ìṣẹ̀ṣe religion of the Yoruba people. Èṣù is a prominent primordial Divinity (a delegated Irúnmọlẹ̀ sent by the Olódùmarè) who descended from Ìkọ̀lé Ọ̀run, and the Chief Enforcer of natural and divine laws - he is the Deity in charge of law enforcement and orderliness

Èṣù is powerful, relevant, and ubiquitous to the extent of having every day of the four-day (ancient/traditional) Yorùbá week as his day of worship (Ọjọ́ Ọ̀ṣẹ̀), unlike all other Irúnmọlẹ̀s and Òrìṣàs (primordial Divinities and deified Ancestor Spirits; "ọjọ́ gbogbo ni ti Èṣù Ọ̀darà".

Èṣù is a personification of Mischief; he is the one who teaches that there are always two sides or more to every issue. He balanced and created directions. That is why it is believed that Èṣù is so necessary to have an ordered life.

Èṣù is always at the middle of divergent world forces. He controls and regulates the two extremes - the world of happiness, joy, and fulfilment, as well as the arena of destruction, hopelessness, and sorrow.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#africans#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#afrakan woman#epic video#africa#yoruba#yoruba spirituality#trickster

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Èṣù é uma das divindades mais belas do panteão yorùbá. Èṣù é múltiplo e possui diversos aspectos e atuações na vida dos seres humanos. Èṣù é o começo e o fim, é sabedoria e dono dos caminhos da vida. . Láarúmo: Senhor da sabedoria e dos caminhos da vida; aquela que tem o poder de unir. Elégbára: O poderoso, aquela que concede poder ao homem para ser bem sucedido. . Bará: aquele que age rapidamente; forte; eternamente vigoroso. . Atúká-M��áṣeàá: aquele que rompe em fragmentos e que ninguém poderá reunir. . Àjígidán-Irin: resistente e indestrutível; aquele que não perde uma única disputa. . Èṣù á gbè wá o! Que Exu nos abençoe! . Imọlẹ Agbara Ife A Força do Poder do Amor . #chrislisboa #umbanda #fe #fé #umbandasagrada #esu #exu #ase #axe #axé #laroye #mojuba #orisa #orixa #calunga #kalunga #pombagira #povodarua #terreiro #belohorizonte #savassibh (em Belo Horizonte, Brazil) https://www.instagram.com/p/CplQg2Tu2VK/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#chrislisboa#umbanda#fe#fé#umbandasagrada#esu#exu#ase#axe#axé#laroye#mojuba#orisa#orixa#calunga#kalunga#pombagira#povodarua#terreiro#belohorizonte#savassibh

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Se você deixar Èṣù "abandonado", ele não te ouvirá quando estiver passando por provações. Èṣù é o movimento e também o caos. Pra sair do caos você precisa de Èṣù. Entendeu? Não entendeu? Existe uma certa tendência no ser humano em se afastar do sagrado quando acha que já "FEZ DE TUDO" e não está sendo "reconhecido" "recompensado". Primeiro ponto a entender é que culto a Òrìṣà não envolve barganha, toma lá da cá, só te dou se me der primeiro. Existe um motivo pra Èṣù ser louvado. E entenda que você, não é um Èṣù. Você não é Òrìṣà. Segundo ponto é que Òrìṣà não fará as mudanças que cabem a você fazer. O caráter é seu, o Orí é seu, a vida é sua. Òrìṣà orienta e apoia. Porém Ele não pode VIVER A SUA VIDA por você. Entendeu agora? Que Èṣù nos favoreça! Seguimos... #ilêaséibádanaràká🌈 https://www.instagram.com/p/Cosqnp_vO0G/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

O MICHAEL [OM]… Eye SEE U [ÈṢÙ] TUTANKHAMÚN [È.T.]

ENQI [ME] NUDIMMUD MU:13

#o michael#OM#quantumharrelltech#harrelltut#kingtutdna#enqiback#9EtherFamilyBusiness#9EtherPentagonElites#9etherlightshipatlantis#9EtherAluhumAnunnaqi#9EtherMU

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nunca esqueça de ÈṢÙ! Esse ditado tem como tradução algo que devemos muito evitar: que ÈṢÙ não toque o sino da discórdia em nossa vida!

Ẹni ènìyàn kí kó yọ̀; ẹni Èṣù kí kó ṣọ́ra!

Tradução: quem é evitado pelas pessoas deveria se alegrar, quem é evitado por ÈṢÙ tomar cuidado!

Sempre é melhor ter a amizade de Èṣù, o favor de Èṣù do que o das pessoas! Com amizade de Èṣù se tem tudo, não é uma falsa amizade.

Já as amizades das pessoas, em sua maioria, são condicionadas!

Educa Yorubá

1 note

·

View note

Text

* GRÊMIO RECREATIVO CULTURAL SOCIAL ESCOLA DE SAMBA ACADÊMICOS DO TUCURUVI

IFÁ

EÈPÀÀ, OJÚ, ÓLỌ́RUN, IFÁ Ó… ÈṢÙ ÀGO

LABAREDA DE IFẸ̀, A FORÇA IGBÁDÙ

ILUMINA MEU CAMINHO E FUNDAMENTOS DE ODÚ

POESIA DE ÌROFÁ SOPROU ALÉM-MAR

TEM DENDÊ NOS MISTÉRIOS DE Ọ̀RUN

ÌRÙKÈRÈ, ÌRÙKÈRÈ

SIMBOLIZA A REALEZA AOS OLHOS DE Ọ̀PẸ̀LẸ̀

ÌRÙKÈRÈ, ÌRÙKÈRÈ

ILÉ BRASIL ÀIYÈ ÀIYÈ

ORÍ CANTA O FILÀ, SALVE MEU BÀBÁLÁWO

TERRA, FOGO, ÁGUA E AR… Ọ̀BÀRÁ

NOS OLHOS DE ỌPỌ́N IFÁ VEJO O FIM DA MINHA DOR

E NA GIRA DAS ÌYÁS, Ọ̀DÀRÀ

RESPEITEM MINHA ANCESTRALIDADE

TOLERE A DIFERENÇA NA RAIZ

MEU SAMBA LUTA PELA IGUALDADE

NO ILÉ DA CANTAREIRA SOU FELIZ

NEGRA CULTURA, NOSSA ESSÊNCIA

NA FILOSOFIA, NA RELIGIÃO

HERANÇA DE IFÁ É RESISTÊNCIA

ME ABRAÇA, SOMOS IRMÃOS

OLÓRÍ, ALAGBARA, OLÓDÙMARÈ

ÀṢẸ Ọ̀RÚNMÌLÀ

A PONTA DA LANÇA IGBÁ DE IFÁ

TUCURUVI LÁRÓYÈ MOJÚBÀ

Compositores: Macaco Branco, Carlos Bebeto, Djalma Santos, Chiquinho Gomes , Dr. Marcello Medeiros e Denis Moraes.

Fonte: http://ligasp.com.br

Ana Luiza Lettiere Corrêa (Ana Lettiere)

Com Patrícia Lettiere ( http://patricialettierepintandonopedaco.tumblr.com ), Paulo Lettiere ( http://osabordamente.blogspot.com ) e todos os nossos inspiradores.

1 note

·

View note

Text

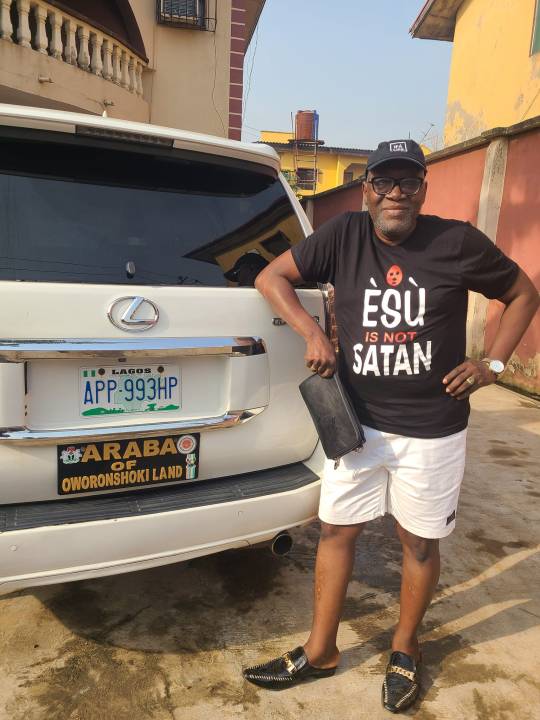

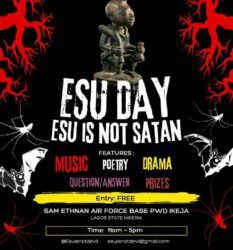

Uploads from #EsuIsNotSatan Day 2023

“Èṣù is not SATAN” day is set aside to create awareness all around the globe against the denigration of who Esu. Esu is not the same as the Biblical or Quranic Satan/Shaitan. During this day, lectures from different people all across the globe are given to people. After the lecture, the walk for Esu takes place on the 24th of December every year. Here are some photos from this year's EsuIsNotsatan.

Araba from Oworosoki land posted the photo above and captioned it with " Today is December 24, 2023. Getting ready to march for ÈṢÙ. The movement is very important to enlighten the ignorants that ÈṢÙ IS NOT SATAN. Just listen to Ọ̀kànràn Méjì Ọ̀kànràn kan níhìn-ín Ọ̀kànràn kan lọ́hùn-ún Ọ̀kànràn méjèèjì ló p'ẹkùn kalẹ̀ Ojú wọn pọ́n kanrínkanrín Adífá fún Láàlú ọmọkùnrin òde làá pé ÈṢÙ Tani yóò kó oore ìlú fún wa? Èṣù Ọ̀dàrà ni yóò kó oore ìlú fún wa One Ọ̀kànràn here One Ọ̀kànràn there The two Ọ̀kànràn killed a leopard Their eyes are so red like fire Cast divination for Láàlú, the great man who lives outside, is the name of ÈṢÙ. Who will bring the blessings of the town to us? It is Èṣu Ọ̀dàrà who will bring the blessings of the town to us. It is good to call him "ÈṢÙ ỌLÁ ÌLÚ /THE WEALTH OF THE TOWN/COMMUNITY/NATION ÈṢÙ IS NOT SATAN" According to Fakayode Esutayo Adewale Igbonla who shared the following on his page and also wrote"

Orisa Esu, on this day we give homage to you. Esu is everywhere. We call him the orisa with many faces. Why?? Because Esu is the representation of divine duality. He is dark & he is light at the same time. He is masculine and feminine at the same time. He can bring miracles, he can bring mayhem. Esu is the orisa that delivers us with choices. He does not make the choice for us. The choice we make is completely our own! So Esu is not evil, Esu is not Satan. Esu provides a choice. Esu reminds us, that our choices have consequences.. so it’s best we make good decisions. It’s very important to appease Esu as much as you can. Why??? When Esu is happy, he will bring you great opportunities, he will bless you with so many doors. However, when Esu is neglected he will close all your doors with a quickness. He will bring you opportunities that may lead to chaos and destruction. Never forget that Esu is the enforcer of ajogun (negative forces) The closer you are to Esu, the further you are from ajogun. The better you treat Esu, the better Esu will treat you. If you want to appease Esu feel free to let me know. As a daughter of this powerful Orisa, it will bring me nothing but pleasure to help others get in his good graces. ORO ESU By ESUTAYO IGBONLA " @Oluwo Ifagboun Ajisafe

ÈṢÙ o Senhor que nos apoia nas encruzilhadas da vida a fazermos as escolhas corretas. ÈṢÙ o inspetor de Olódùmarè. ÈṢÙ o que transforma erro em acerto, acerto em erro Aquele que exalta os humildes e ri dos arrogantes e hipócritas. Que tenhamos sempre alegria, vitalidade, que cumpramos nosso destino. Quem tem alegria reserva para ÈṢÙ a sua parte (aprenda a ser grato). Quem tem riqueza dê a parte a ÈṢÙ ( a comunidade ). Quem tem alimento, dê a ÈṢÙ a sua parte ( aprenda a compartilhar). ÈṢÙ o justo. ÈṢÙ o melhor amigo ÈṢÙ o pior inimigo de nossos inimigos. ÈṢÙ me conduza sempre ao bom caminho. Saúde, trabalho e vitórias não faltarão em nossas vidas. Seus mais profundos sonhos se realizarão pelo poder de ÈṢÙ e pelas bençãos concedidas por Olódùmarè. Que ÈṢÙ abençoe grandemente sua vida! / !!! Oluwo Ifagboun Ajisafe / !!!

@Ifatola Sangodare Awosipe Èsù is not satan

Èsù the mighty divinity and executioner Òrìsà In yoruba theology and traditions Are of the highest divinity . And must be respected and adored . Òsè ifá Òsè èsù Òsè ire gbogbo . Àse òrìsà

Video upload "If there is a connection between Esu and anybody in the Christian religion it will be Jesus" says Araba Ayobami Ogedengbe in the just concluded walk for Esuisnotsatan in Akure @Akinola Taiwo Ifafunmilola

Another Esu day has come. Do not forget to tell someone that Esu is not Satan. Esu did not rebel against Olodumare. Esu was/is in fact a best friend to Orunmila who is the custodian of Ifa which is the voice of Olodumare. Everything that comes from Esu is perfect! I AM ONISESE AND I BELIEVE ESU IS NOT SATAN Stop the confusion now,Esu is olailu (source of wealth for all nations) Omo esu ni mi

Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

MEDITATIVE WEEK OF POETRY: SODÏQ OYÈKÀNMÍ

it was a monsoon season. there was tears flood. & anywhere could be an entry point as long as there was a raft. the polyrhythmic sound of the rain could pass for music—say jùjú or sákárà. there was a cavity in our canoe—the exact size of my mouth when i saw màámi—neck-deep—in the water—ah! olúwa gbàmí. depending on how far the music have travelled in the body, flood tears could become the lyrics spilling out from the eyes. if reflected on water—the shadows of people screaming & tapping their feet for help could be mistaken for a dance. drowned chorus. drowned chords. drowned hearts canoes. omi ò lẹ́sẹ̀ omi ńgbégi lọ. i pulled her into the canoe & everyone was swimming to safety—even a dog backed a chick. i pulled them into the canoe. ọjọ́ burúkú èṣù gb’omimu. our village—filled with enough water that could dampen 7.9 kilometres of the sahara for the growth of wisterias. olúwa, we didn’t kill no albatross. why send a flood without warning—without an ark? everywhere could have been an exit point—as long as there’s dryness on the horizon, but there was a cavity in our canoe—our hearts. our prayers—bloated & unanswered—

monsoon— a praying mantis splits open God’s eyes

0 notes

Text

RE: The Origins of American Papa Legba

Unlike my previous posts, this one is about the actual deity Papa Legba.

Upon further investigation, it appears that American Papa Legba (Papa Limba / La Bas) is indeed an amalgamation of Dahomean Legba and the Yoruba trickster god Eshu (Èṣù). This is because he traces his lineage to Haitian Papa Legba. In Haiti, Dahomean Legba was refracted into Haitian Papa Legba, Kalfou, and the Gede; as far as I can tell, this refraction was not transmitted to America. This would explain why American Papa Legba retains more aspects of Dahomean Legba, and is similar to Haitian Papa Legba AND Kalfou. Prior to the 19th century, New Orleans Voodoo had little Dahomean influence, being mostly a fusion of Senegembian and Kongolese traditions. Following the Haitian Revolution, a huge influx of Haitians arrived in New Orleans, bringing with them their deities and religious practices. “The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population.”

This is why Marie Laveau-era New Orleans Voodoo is this fascinating amalgamation of Senegembian, Kongolese, Catholic, and Haitian traditions. It is for this reason that American Papa Legba is portrayed in a similar manner to his Haitian counterpart, where he is depicted as a limping old man who carries a crutch. But unlike in Haiti, there is no American Kalfou. Papa Legba is the Doorkeeper AND the guardian of the crossroads, and it is obvious that he is not actually feeble. The reason he limps is because he has one foot in the world of the living and one foot in the spirit world; his crutch is actually his key to the “door” between the two worlds. (He’s literally just pretending to be an old man!) There is also a very playful side to his personality, where he’s literally described as pranking children. His love of dogs, music, and fun can all be traced back to Dahomean Legba. He is completely terrifying when he is angry though! A lot of the best horror stories to come out of Voodoo involve Papa Legba’s bad side.

There is a nonzero probability that ROBERT D. JOHNSON is getting tortured for eternity by Papa Legba as we speak!

Deities such as Papa Legba, Dahomean Legba, Elegua, and Kalfou can all be categorized into a group with shared origins in the Yoruba deity Eshu (Èṣù). Although they have diverged from each other, it is common for sources to use the terms “Legba” “Elegua” and “Eshu” interchangeably. As such, it is possible that I have incorrectly confused “Eshu” with “Elegua” in some places. Sorry for the confusion.

FULL CITATIONS FOR SOURCES MENTIONED:

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365

Haitian immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The African-American Migration Experience. (n.d.). https://www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm@migration=5.html

#commentary#the loa (hazbin hotel)#big papa legba#you have no idea how badly i want my deviantart oc to be in the canon of this fucking show...!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sugestão para caso alguém queira me dar um presente... 🥰 #Èṣù #Exu #Funko (em Santa Maria De Benfica) https://www.instagram.com/p/BtEsqJCBcWc/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=gnudl9awcfik

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ọjọ́ Ajé - Segunda-feira. Èṣù guardião dos caminhos, nos traga proteção na semana que se inicia!! L'arọyè Èṣù l'ọnà Ojìṣẹ Òrìṣà gba mí ọ!! Èṣù ma ṣẹ mí- Exu não me trái! Ojìṣẹ Òrìṣà ma ṣẹ mí - Mensageiro dos Orixás não me trai! Si tun ọdàlẹ gbigbọn mi - Ainda me alerta de traidores!! L'arọyè!!! Uma ótima semana de força e perseverança! #ilêaséibádanaràká🌈 #exu #iniciodesemana #segundafeira #proteção #salvador #bahia #brasil #carnaval #exucarnaval #oferenda (em Salvador, Bahia, Brazil) https://www.instagram.com/p/ComkQiXOjn9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#ilêaséibádanaràká🌈#exu#iniciodesemana#segundafeira#proteção#salvador#bahia#brasil#carnaval#exucarnaval#oferenda

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Èṣù : The One who can give you the right information you need to move ahead and the one that can block the right information from reaching you for you to crash. I'll show you how he operates with this simple scenario: In the beginning (ìgbà ìwáṣẹ̀), the Plantain tree used to be barren, that is, it wasn't producing any fruits, so she went to meet Babaláwos to help her so that she can have children. The Babaláwos consulted Ifá-Olodumare to inquire about plantain's situation. Ifá revealed to the Babaláwos that Plantain will bear children if she offers the appropriate sacrifices. But an additional information was given to her - she is to offer another sacrifice so that she'll not die on account of the children. She made the sacrifice to have children but didn't offer sacrifice to ensure that she doesn't die on account of her children. She considered it impossible for her own children to kill her. She did bear children. Read more in comments. Ayobami Ogedengbe (c) 2021 #orisamagazine #orisa #orisha #orisaculture #esu #eshu #Èṣù #ireteoyeku #oduifa #ifadiaspora #bornorisa #orisaborn #abundancechildpublishing 📷:: © @eyeofifa 2018 https://www.instagram.com/p/CQ7ytkusg3K/?utm_medium=tumblr

#orisamagazine#orisa#orisha#orisaculture#esu#eshu#èṣù#ireteoyeku#oduifa#ifadiaspora#bornorisa#orisaborn#abundancechildpublishing

0 notes