Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Did the HK Observatory play with its Typhoon signaling? A quick look

Typhoon season was a big part of my upbringing in subtropical Asia. They are quite dangerous and occasionally deadly. However, as a kid I was quite excited whenever they came. If a particularly Typhoon is strong enough, the Observatory would put out signals 8, 9 or 10 (higher signals mean stronger Typhoons - out of 10), canceling school (and work for most industries). I would then stay home all day and play video games. Since I lived close to the sea, it was also just fascinating to stare at the choppy waves.

There are all sorts of urban myths about Typhoons. A popular one in Hong Kong is the “Li’s force field”; named after Li Ka Shing, the wealthiest tycoon in Hong Kong. Li supposedly has the power to swat Typhoons away when the strong ones get too close, hence robbing everyone of a free day off and preserving the city’s productivity.

The other myth is also about productivity, but just much darker. The rumor is that the Hong Kong Observatory deliberately refrains from busting out stronger signals during working hours so that everyone would go to work. This is quite a serious allegation, since it accuses the Observatory (hence government) of putting productivity ahead of the safety of citizens. Before looking at the data, I thought that this is probably bullshit. I wholeheartedly believe that the Observatory is a professional organization, and that the officials there do their best to be conservative, especially given how easily one could get hurt in a typhoon.

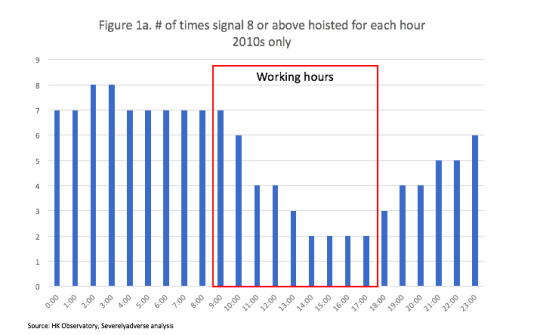

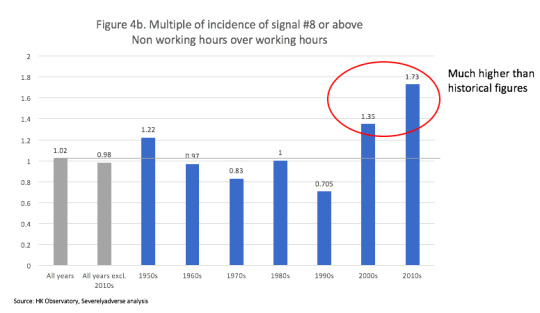

Using the Observatory’s own data, however, a fairly shocking picture emerged. (Note that the Hong Kong Typhoon warning system comprises of signals 1, 3, 8, 9 and 10. School and work are usually cancelled for anything at or above signal 8. Signals 4, 5, 6, 7 are not used). First off, the incidence of signals 8 or above is dramatically lower during working hours in the last 7 years – see chart 1a. Effectively, we were 1.7x more likely to have signals 8 or above during non-working hours vs. working hours (normalized for number of hours).

Warning: for all you consultants, I did this on a Mac MS Office, which is rubbish, so please don’t complain about my graph formatting

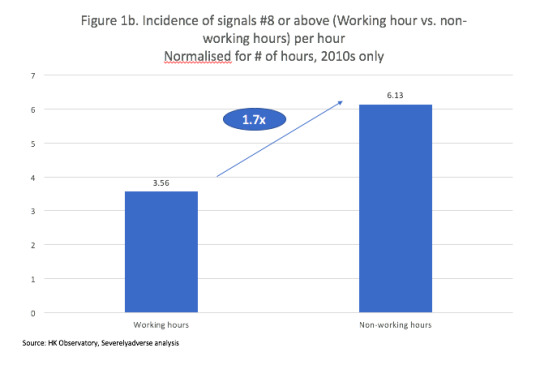

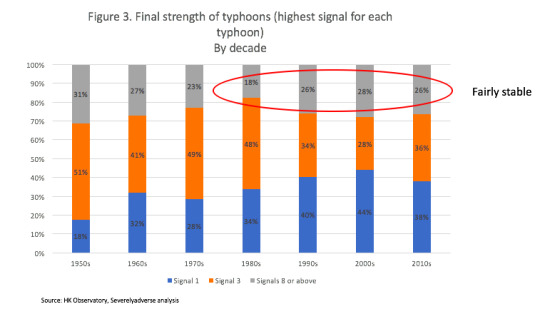

Perhaps we have been getting weaker typhoons compared to average? Figures 2 tells us that this is likely not the case. As a percentage of total time under typhoon, we are spending about the same amount of time under signals 8 or above, ~5-10%. If anything we are spending a bit more time in the stronger signals compared to the previous decade. Figure 3 also shows us that the distribution of typhoon strength is about average in the 2010s, with about 26% of typhoons eventually converting into signals 8 or above.

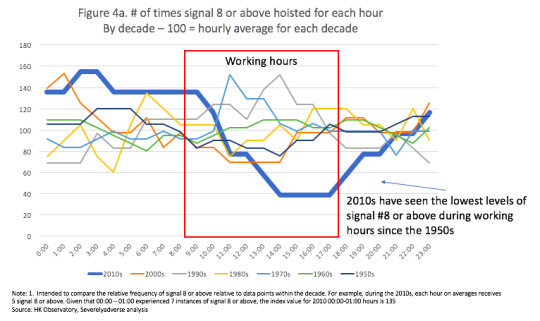

Perhaps the distribution of typhoon signals over the course of a day has always been this way? That also is not true. While there is some evidence that there was a similar trend in 2000s (less pronounced), this was clearly not the case in the 4 decades before this – see chart 4a. The ratio of incidence – chart 4b (same as chart 1b, just plotted over time) shows that the last 7 years were indeed quite unusual in how unlikely it was to get signals 8 or above during the work day.

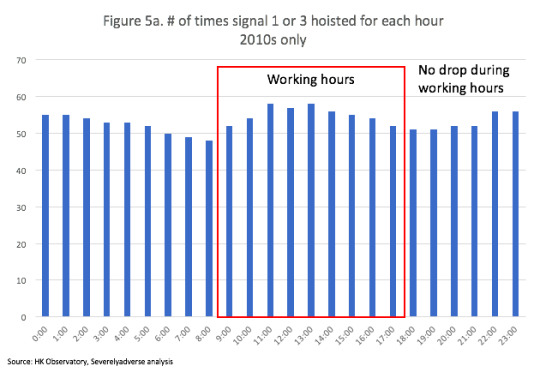

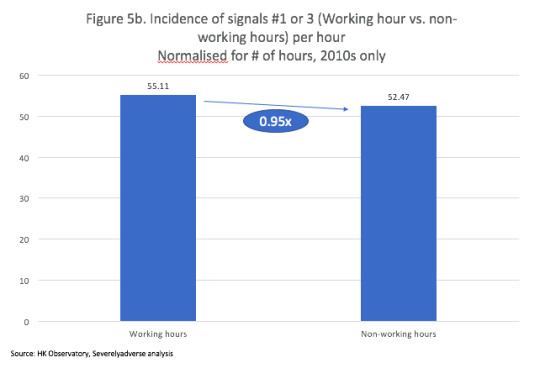

I am no expert in typhoons, but I find the idea that Typhoons are more likely to come at night a bit bizarre. In fact, if you just look at the data for signals 1 and 3 (see figures 5a and 5b), you see that the same analysis above produces a fairly uniform distribution.

Very suspicious huh? I still don’t believe that there is conclusive evidence that the Observatory has been manipulating typhoon signals for economic gains. However, there is certainly reason to look deeper into this.

The definitive proof would be to get historical weather data, apply rules for each signal (which are public), and backtest that against the actual signals hoisted by the observatory. That weather data seems pretty hard to get, so I didn’t do this here. Once the data is in place, this analysis is actually probably really straightforward. Hong Kong Observatory – if you are somehow reading this, this would be a quick way to clear your name.

There are also other alternative explanations. For example, weather systems are notoriously hard to predict – so depending on how much the signaling process is based upon “expectations”, models might introduce some noise into the ultimate signaling decision. However, I find it extremely hard to believe that the models somehow have a time bias and that we systematically expect less severe typhoons from 9-5pm. It’s just too strange to believe.

The other explanation could be that the Observatory is not aware of its bias. Given that signaling is ultimately a bit of a judgment call, worries about false positives (hoisting signal 8, but then nothing happens -> Observatory looking like a fool) might have creeped into the decision makers’ subconscious and lead them to be more conservative. This is definitely plausible, depending on how the decision making is actually done.

The other explanation is that we are just getting loads of weird Typhoons that approach HK at night. But again, I would think that charts 5a and 5b disproves this.

The data only covers 6 years out of the possible 10 for the 2010s, let’s see how this plays out in the next few years.

Finally, random canto song about the wind – not really related at all but it’s awesome:

youtube

Raw data here for anyone interested: http://www.hko.gov.hk/wxinfo/climat/warndb/warndb1_e.shtml

1 note

·

View note

Text

In a different key

Autism has always been around me. It seemed like this mysterious condition that blocks the gears spinning in someone’s head. Even from the outside, it is clearly a life changing condition, both for the individuals and their families. It’s a condition that I’ve been interested in, but never took the time to learn about. Fortunately, Caren Zucker and John Donvan, both parents to Autistic children, did all the leg work for me in their account of Autism, In a different key.

The blue puzzle piece, often used by autism charities as a logo

What is Autism? This is a surprisingly complex question. Indeed, the definition of autism has changed significantly over the years. The main challenge is that autistic traits are not binary, but rather a spectrum of behavioural characteristics. Autistic individuals can include any combination (both incidence and severity) of traits such as aversion to making eye contact, bouts of tantrums, tendency to hurt oneself, limited capacity for verbal / auditory communication, lack of a theory of mind, etc. Some autistic individuals lack the capability to form a complete sentence, while some can be extremely articulate, and even become masters of particular subjects (e.g., Temple Grandin, a cattle expert usually associated with having Asperger’s’ syndrome, in one end of the autism spectrum). In a different key does a great job explaining how the medical profession and the public navigated this messy landscape of traits, progressing from calling everyone mentally feeble or “retarded” to the more nuanced definitions used today.

What surprised me, however, was our lack of understanding of the underlying causes for Autism. I don’t mean to say that all autism treatments are voodoo medicine. Psychologists and Psychiatrists have developed a whole host of interventions like the Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA, basically conditioning autistic individuals to stop certain behaviour such as hitting oneself) that worked wonders on many, and certainly improved from the defeatist approach of just institutionalising autistic children for life. However, today we still don't understand the genetic or biological basis of the condition. We know the symptoms but not the cause. In some forms of cancer, we understand which exact genes can become “stuck” and cause abnormal tumor growth. This allowed doctors to move from just aggressively hacking away tumors (only for more to grow back) to more targeted therapy on specific cells and genetic pathways. In Autism, given our limited understanding of its mechanics, there are many things that remain unexplained, e.g., why infants tend to develop seemingly normally until they reach age 1-2 then suddenly regress and why autistic individuals seem to lack a theory of mind1. As a result, some of the treatments used in the past, while no doubt backed by theories (often with little supporting evidence), have not withstood the test of time. For example, it was common in the 60s and 70s to blame autism on “refrigerator mums”, who supposedly didn’t show enough affection for their children and caused autism. Other even more ridiculous treatments like facilitated communication (helping autistic children type out messages instead of speaking, which proved to be bogus) and embrace therapy (literally hugging your kid more) also became popular only because we don’t understand autism's causes. More than anything, In a different key shows that medicine today is still a work in progress.

Flipping through the book, it also struck me that medicine is as much of a scientific endeavour as it is a social movement. While many of the doctors and psychologists deserve credit, their work wouldn’t have been possible if without motivated activists promoting their causes. The real heroes in the autism battle are the concerned parents who first started clamoring for more research into the condition and relentlessly sought public attention, all while taking care of autistic children. This is not unique to autism. Again looking at cancer, one could also clearly see the impact of activism. However, what’s clear from the book is that activism still takes a long time – in the case of autism, the fight for more research and treatment has been raging for 70+ years. Nor is the path towards “cure” or more successful interventions a straight one. Reading through the stories of autism organisations coming and going and NGOs fighting each other, I got the sense that we are on a journey that is progressing in the right direction, but only over a long time. What’s also interesting is that Autism research has largely been done in the US and the UK. I do wonder how the process would have played out in countries where the lobbying / research grant system is not as developed.

In a different key is a very interesting book on autism in layman’s terms. Well worth a read.

1. Apparently, some autistic individuals lack a theory of mind. This means that some autistic individuals cannot think from other’s perspective. See the Sally-Anne test for how this is tested – super interesting. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sally%E2%80%93Anne_test

1 note

·

View note

Text

Three short stories

I have three personal stories for you.

First story: I had a strong interest in international development in college. For me, the field seemed to offer me the best chance of marrying the desire to make a difference, and using my academic training. I applied to a few internships with international development NGOs / consultants, but none of the places took me. So I volunteered instead – spending time in Nicaragua and Cambodia. In Nicaragua, I mostly did random accounting work, which involved adding numbers together for a fair trade coffee cooperative. In Cambodia, my work mainly involved writing proposals for a struggling microfinance institution which was thinking about expanding into the eco-friendly latrine manufacturing business. It was very fun, and from a cultural exchange point of view extremely rewarding. However, I always struggled to articulate what difference I actually made. More than anything, I realised that making a difference takes a long time, takes more than good intention, and requires dedicated focus / resources / networks that are almost impossible for foreigners to provide over a short period of time. I felt that I was helping out more for my benefit, than for the locals’. An article (“The reductive seduction of other people’s problems”) I read sums it up nicely

“If you asked a 22-year-old American about gun control in this country, she would probably tell you that it’s a lot more complicated than taking some workshops on social entrepreneurship and starting a non-profit. …But if you ask that same 22-year-old American about some of the most pressing problems in a place like Uganda — rural hunger or girl’s secondary education or homophobia — she might see them as solvable”

I realised that solving social problems is extremely difficult, and that I am probably better off focusing on problems that I have the understanding, resources and networks to solve, rather than sticking my head into grandiose, international problems.

Second story: Growing up in Hong Kong, I had a fairly standard local upbringing. I went to a local secondary school with a student body that was almost 100% Chinese. Since my school was started by missionaries, everyone around me was mildly Christian, or sometimes Buddhist / Atheist. When I thought about Muslims, I thought of two things – the planes flying into the two world trade centres, which I thought was a movie; and the big Mosque in Tsim Sha Tsui, which played loud, strangely convoluted melodies at weird times. The first day I moved to the US, I was sitting underneath a tree outside of my dormitory, reading a book. The orientation programme for international students started earlier than the regular one, so the campus was basically empty. Late in the afternoon, I saw these two guys dragging a broken suitcase along the pathway leading up to the dormitory. They couldn’t get in and looked confused. I remembered the advice I read on CollegeConfidential about being proactive and making new friends, so I offered them some help and beeped them into the dorm. It turns out that one of them was my next door neighbour. He’s Turkish (and of course, Muslim), and has shoulder length brown hair and coloured eyes that made him look like the short version of Jesus. Some friendly voices from home kept telling me, jokingly, that I was going to get attacked by terrorists. But I liked this Turkish friend of mine, who likes Japanese anime, plays football with me, was subject to many of my lame jokes and showed me a face-recognition drone he built (sadly the drone didn’t recognise Asian faces too well). We continued hanging out intermittently throughout College, and he was the last person I said goodbye to before I left the campus. He is a devout Muslim and opened my eyes to a different culture and belief system. I am glad to have met him.

Third story: I was a Government major, which means I had to read a lot of random articles and argue in sections. Most of the stuff I read was interesting, but sometimes I found the material quite dry and too theoretical (political philosophy was a nightmare). There was this one article, however, that really stuck with me. It’s an article about the Rwandan genocide. I must confess that at that point I knew nothing about Africa – the nuances of country-specific politics were beyond me. However, as I read that article in Libe Café in Uris Library, I remember myself trembling in anger. Because of politics, apathy, and our general lack of understanding of the continent, the rest of the world stood by while the Hutus murdered a million Tutsis. I thought this was really stupid, for the lack of a better word. If only we did something. But then I remembered this theory I read about in Psych 101. The theory argues that when we are in a crowd, it is easy to feel deindividualised and not take responsibility for things happening right in front of us. “No one knows that I am doing nothing. Look at all those people around me also doing nothing.” That day in Libe café, I prayed that I would have the courage and strength to stand up to the problem, if I ever come to that point.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the world

The silence. The loud scream that you keep within your head.

The feeling of being punched in the gut. The sense that something strange is going on, but that the people around you are somehow acting like nothing happened.

For some reason, it’s always a rainy day as well.

Brexit, Donald Trump, a disintegrating Europe, rocky politics in Hong Kong. It seems like the liberal world that I was born into is slowly descending into chaos. A dark part of me thinks that we are perhaps just getting into a part of history that is full of conflict and insecurity, that if you zoom out enough this is nothing but a blip. Somehow, though, this blip looks like a tsunami up close.

Why is this happening? What will happen? More importantly, what can we do about it? Many more intelligent people will weigh in on this over the coming days, but bear with me while I intellectualize. This is the only way I know of to ease the hollow feeling in my stomach.

So what is the problem? Of course, Brexit and Trump came about in different contexts, but I believe they are the manifestation of the same underlying current. In a nutshell, the core problem is inequality / economic polarization, which drives a backlash for “outsiders”. This problematic combo is then made worse by the fact that the liberals, or the elites are blindsided by our media landscape.

Let me explain.

There are two dimensions to inequality. There is the intracountry aspect of inequality, which is quite well documented and increasingly becoming a center-stage issue. One can see the growing importance of this by the huge popularity of “Capital in the 21st century”, the divide between London and non-London UK, and the urban / rural divide in the US. However, there is also the intercountry aspect of inequality. I don’t think people fully appreciate the impact of this in the US. The reason why the UK has so many immigrants is because its economy is much stronger than the rest of the EU, and have more jobs. Just ask all the Italian architects in London. The bigger the difference between economic payoffs within an area that allows migration, the quicker migration is likely to be. In the US, this “economic payoff potential” is the primary reason why it’s the land of immigrants. The effect of both types of inequality is that we have a group of people that feels left behind together and lots of people that want to get in.

As a particular segment of locals start to believe that their livelihoods are under threat, they start to think “OK - ’we’ better protect ‘ourselves’”. The critical idea here to pay attention to is what “we” means1. In the UK, the Brexit folks seem to have come to the conclusion that “we” means the British. In the US, however, a sizeable amount of working class families that feel disenfranchised seem to define “we” as Americans, and IN PARTICULAR, white Americans. We then get this spectacularly ugly yet explosive mix of racial / economics / religious2 driven resentment in America. I’d argue that the British definition of “we” is wider than that of the US, and therefore we seem to see less racial backlash here. In both countries, however, the common thread is that the “outsiders” are immigrants and are best kept out. This impulse to protect oneself clashes bitterly with the diversity, internationalist view of the world that many Liberals hold.4

In today’s media and social media landscape, we have also become much better at isolating ourselves from one another. If you only want to read Liberal news, you can entirely avoid “the crazies” by avoiding Fox news (and vice versa). Social media like facebook have also become so good at tailoring to our preferences that they essentially turn into echo chambers. To hold our eyeballs, we are only shown what we will like. To be fair, I think knowing more about this ugly nexus of problems would probably not have helped us avoid this spectacular rupture. Like I said in my previous post, people suck at solving important but not urgent problems. Problems of this kind that takes many people to solve are even harder. However, the fact that the urban elites are blindsided by this does contribute to the shock factor that we are all feeling now. In a way, it probably leads us to overestimate how shocked the whole world is.

So what do I think will happen?

Since it all starts with inequality, let’s start from there too. How can we solve inequality? That’s so broad a question that I already feel stupid trying to answer this. But the real question is – how are we likely to attempt to solve inequality? We know that people don’t have the patience for long term fixes like re-skilling and reforming the education system. Therefore, the most likely scenario is that trade barriers will go up, and we will see the government call it a day. Of course this just kicks the can down the road – but having worked in a number of big public exercises myself, my (not the most optimistic) view is that 9 times out of 10 that’s what governments do (think EU financial crisis, US government debt). To tackle intercountry inequality is even more impossible for a single government. However, given the real effects of this “economic payoff potential”, the temporary solution will probably be to put up higher immigration barriers. Is it going to solve the intercountry inequality problem? No. Is it going to stem the flow of immigrants? Probably yes – and it’s a visible thing to do to placate the angry crowds with pitchforks, guns and votes.3

For the media, I think there is enough of a shock from this time that people might seek to burrow a hole through the walls of the echo chamber that we live in. However, I have no clue how and whether those will be successful. The core, and most interesting question is – what do you do once you have burrowed through that wall? To me, this issue of persuasion seems to be the question of our generation. For example, if you (assumed to be a NYC, college educated Liberal) were put in a room with a Trump supporter, what do you think you could tell him that you think will change his mind? Similarly, if a democrat in Hong Kong were put across the table from a conservative pro-China LegCo member, how would you attempt to convince them? At this very moment, I don’t have a good answer to these questions. My initial thoughts are that we need to get a clear sense of why we make different choices. Is it policy? Which policy? Is it some non-policy issue like loyalty to the party, or perceived career mobility? This strikes me as the most interesting intellectual work that one could do as we approach the end of 2016. Once you know what moves the needle for the other side, you can either try to change their “value” function, or you can try to trade on some of the issues.

Spectacularly useless suggestion – I know5.

In a way, this makes me despair. In another way, seeing what I think is the challenge of our generation is strangely exciting.

We keep walking.

1. This has been a trendy theory with me lately. I think it also explains why some people (myself included) feel that Chinese people are less likely to help one of their own compared to other Asians. But let’s not get bogged down here today

2. I’ll say it – it’s basically anti Muslim. But other minorities should definitely definitely be very alarmed. It could be any other group outside of what “we” is

3. The second order effects of all this will be extremely interesting to ponder upon on another night. I feel that this may also be a more scary thought experiment

4. I feel like we are dealing with the same problem over and over and over again all over the world. One could argue that Hong Kong has a similar problem with economic stagnation and local kids defining “we” as people from Hong Kong, rather than ethnic Chinese. It’s xenophobia exacerbated by economic frustration. This also explains why people use language such as 自決

5. In case you haven’t guessed it from the number of footnotes, I am a consultant

PS: In case you are wondering where the title of this blog post came from (great question! Glad you asked!), I recently read a great great great book called “This is London”. It completely changed my view of the UK and London. If you’ve spent any time in London, read it. Brilliant prose as well. Cannot recommend enough.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Warning: Important, complex but not urgent

Nudge is about applying insights from behavioral economics to public policy design. I thought I wouldn’t like it, since I really didn’t enjoy Psych 101. Though I had fond memories of sitting on the steps of Bailey Hall with one of my good friends, memorizing a thousand “groundbreaking” papers that, to me, argued for something really intuitive, was sheer nightmare. Nudge proved me wrong, however. It offers original insights and does not try to hide simple insights behind big words and long winded academic debates.

At the core of Nudge is the idea that humans are predictably and consistently inept at choosing the right solution for some types of problems. In particular, problems that are long term, that are really complex, that offers little immediate feedback or that do not happen often are particularly tricky. In other words, problems that are important, complex but not urgent. Nudge argues that by presenting choices in specific ways that address our weaknesses, the government can steer us into more optimal behavior.

This got me thinking. On a personal level, what are things that are important, complex but not urgent? Having read Nudge, I am fairly certain that I am not paying attention to something.

Money: This is exhibit A of problems that are important, not urgent and also complex for obvious reasons. I have a rough sense of how much I make, and how much I spend. But am I saving / investing enough? Assuming that I want to buy a house / retire at some point, what is the right savings / investing strategy? I am almost sure that I am underinvesting

Health: Exercise and diet are probably key, but I don’t really pay attention to any of this. Perhaps lying in bed vs. running for an hour could have a real impact on my wellbeing 40 years down the road. But who’s there to tell me that?

Relationships: The Harvard Grant study pointed out that the strength of your relationships is THE most important determinant of happiness. Yet, how much effort do we put into maintaining these relationships? Have we lost touch with people that are important? Have we really thought about this enough? Relationship maintenance is tricky because it is so long term, and on a day-to-day level, we could largely get by without thinking about it. Read this blogpost here from WaitButWhy if you think you’ve been thinking about it enough

Spiritual: At the risk of sounding like a millenial, how much time do we spend thinking about what gives us meaning in life? How are we steering our lives towards what we think is meaningful? For some, this is about religion, for others, self-discovery

Work: finding mentors at work, paying attention to the bigger picture, etc. instead of focusing on finishing the next deck. Though given how much time we spend working, we are largely aware of the pitfalls i think, rather optimistically. In fact, one could argue that most of us pay too much attention to this

We have probably all met people who are obsessed about one of the things above - people who are health nuts / will only eat raw vegetables, people who pinch pennies, etc.. However, I personally haven’t met anyone who I think has a good grasp of all the things above. Admittedly, hanging out with a compassionate raw vegan penny pincher sounds like another level of hell. Yet, I suspect that this is because, absent of an easy way to monitor your blindspots, paying attention to these long term problems requires lots of obnoxious, deliberate effort. So much so that a lot of the health nuts have to keep talking about kale, going to yoga, drinking soylent etc. to remind themselves of where they stand and where they need to be.

What if there is an easy to use personal blindspot map of key things that you should pay attention to? What if we can do choice architecture for individuals? Imagine something that every week sends you a report card on how you are doing on the important problems that are proven to have a significant long term impact on your wellbeing, and shows you little things that you can do to keep them in check. It would almost be like figuring out the common life pitfalls all in one go. Each individual would be able to avoid reinventing the wheel, or worse still, discovering at the end of one’s life that one should have done X. Remember, being smart doesn’t help you solve these problems. We are hardwired to fail to solve these problems.

Go read Nudge.

In the next post I will talk about one of the things on my list above: Relationships. Stay tuned.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Starbucks’ New Rewards Program

Starbucks unveiled its “exciting new” rewards program last week. Historically, the program had granted one Star per transaction to Starbucks’ Gold customers, and 12 Stars could be redeemed for a free food / drink. Now, customers receive 2 Stars per dollar spent, but 125 Stars is the new redemption price for a free food / drink. Though Starbucks spent a lot of effort branding the new program as something customers had requested and a good thing for the customers (Gosh, even the url for their new program starts with “morestars”), most customers are unhappy (see: https://secure.marketwatch.com/story/starbucks-changed-its-rewards-program-now-what-2016-02-26). It’s an end to a system that frankly didn’t make economic sense to Starbucks.

Exactly what amount of first-world anger should I direct toward Starbucks? I was curious about how the new program would affect different types of customers (ok, specifically me), and came up with a simple model here:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/14fLCbN6tz6v1ttI-lt0s-pqwHilZSUaoesxdcXfQKTQ/edit?usp=sharing

Here are my findings:

1. Because of the spend requirement, the new program fixes the % back a customers receives on his/her purchase. In the new regime, one accrues ~8.76% back. This is pretty comparable to other coffee shops (1 free drink every 10 - 12 drinks)

2. The break-even point between the old and new regime is $5.21 per transaction. In other words, those spending on average $5.21 are indifferent between old and new plans. Those who spend more than $5.21 per transaction should actually be happier under the new program. Those who spend less than $5.21 per transaction? Not so much. The $3-latte drinkers are worse off by approximately 5%. The $2-cup-o’-joe drinkers are worse off by approximately 13%.

3. To even start to have purchase count toward rewards, Starbucks has a spend threshold in place. The switch over to dollars spent means that the $3 latte drinker has to spend an additional $55 to even get into the program; the $2 cup-o’-joe drinker, an additional $90.

Such a move is not dissimilar to how airlines changed their frequent flier miles to be based off of dollars rather than miles. It makes sense to the companies running such rewards programs, particularly toward the end-goal of rewarding the most loyal customers, rather than their most frugal / enterprising customers (i.e., those that would split purchases into separate transactions to get more Stars. Guilty as charged! Starbucks even has a special FAQ / go to hell note for these customers here: http://morestars.starbucks.com/). Given 95% of customers likely fall under the $5.21-per-transaction threshold laid out in point 2, I’m surprised Starbucks didn’t go even deeper (say, to a $7 break-even point) under the new system. My two theories:

1. Optics: they adjusted the numbers so that it wouldn’t look to start (125 stars relative to the 12 stars sounds better than 250?)

2. $5.21 is the roughly the minimum per-transaction spend of a big-fish Starbucks customers whom Starbucks would like to make feel special

Based on Starbucks’ push to get customers to adopt the mobile app and the reward system, they continue to see this as an effective program to keep customers “subscribed” to coffee. I wouldn’t be terribly surprised if another change to the program were to occur in the next few years, whether it’s another inflationary Star-value event, or an increase to the purchase threshold for Gold. Since Starbucks has started to offer other benefits that regular coffee shops can’t offer (mobile ordering, Spotify integration), it has less of a need to lead the charge on rewards through its loyalty program.

1 note

·

View note

Text

「能走出去的話,千萬不要回來」

最近,身邊有好幾位長輩和朋友跟我說:「能走出去的話,千萬不要回來」。幾次聽到,都驚訝得好一會說不出話來。以獅子山打不死精神稱道的香港人什麼時候變得如此悲觀?

希望是一個抽象的政治指標,但對於一個社會的前景卻非常重要。越有希望的人,越容易看到眼前問題的解決方法和社會上長遠的需要,越願意接受短期的痛苦以換取長遠的利益。相反,假如香港人對社會前景的希望越趨悲觀,那麼社會上埋怨、挖苦的聲音對比起積極的聲音只會比現在的更大。累積著的負面情緒很容易就會演變成排外、短視的民粹主義,一發不可收拾。

社會希望的根基有兩個:第一,港人需要相信未來會更好;第二,港人需要相信自己的行為對未來有一定的影響力。不幸的是,種種跡象顯示港人(尤其是年輕人)心中的希望正隨著這兩個根基的動搖而變得越來越黯淡。

今天的香港真的相信未來會更好嗎?無論是從數據、或者是社會上的語氣看來,香港對未來的觀感都難言樂觀。港大民意調查顯示,香港人對前途的信心已經下滑至10年來的低位。有人可能會說,經濟好起來的話,民心自然會回歸。但比起2007年金融海嘯的時候,香港經濟的確好了(人均出口總值從07年到13年增長百分���二十四),但訪問中有信心的港人反從07年高位的百分之七十九大跌至最近的百分之四十八。在網上社交媒體上,不難發現年輕人的留言都非常負面。受歡迎的新媒體,例如毛記電視等,都是走挖苦公眾人物、挖苦政府的路線。

在第二點上,香港有一部分的年輕人今天對自己努力��看法可以用一句話總括:「成功需父幹」。因為樓價繼續高企,社會流動性又有減弱的跡象,香港有一些年輕人卻越來越不相信自己努力能改善自己的未來,也不相信港府有誠意、有能力扭轉乾坤。在這方面,政府實在是責無旁貸。在政治事件上,(如最近書店店東失蹤事件上等大是大非的事情上)政府擺出的曖昧姿態,比起推行具爭議性的政策時用的力度在觀感上差別很大;直接令年輕人懷疑政府最關心的到底是自己在中央眼裡的形象,還是港人的未來。在政策層面上,政府民生政策上推行又進度不足;加上部分建制派議員連連出醜,更令政府顯得左支右絀,好像僅靠幾個滿口胡言、發言刻薄的小丑盲目支撐。面對經濟上的困境,又覺得政府幫不了忙,香港年輕人感到灰心並不令人意外。

香港人對未來失去信心,社會上的聲音自然趨向負面。政府在大小政策上不是沒有努力,但在負面的社會氣氛下,每一個討論的機會都被標籤成對政府認受性的終極投票。「政府建議」變成每一個議題最大的毒藥,事倍功半。年輕一代討論的不是一個政策本身的優缺點,而是行政長官如何不民主,建制派的幾位小丑出的洋相。這樣下去,香港被自己的恐懼、不滿所困住,前景更加堪憂。

香港政府推行的政策通過、成功推行與否當然對香港的未來有重要的影響。但這任政府成功與否的關鍵不在於能否把下一個方案成功通過立法會,而在於能否重建港人對港府、對未來的希望。到了這個地步,這不是政策,而是形象、觀感上的問題。

但願香港不會在中國追逐中國夢的大前提下,一步一步的踏進自己的惡夢當中。

後記:投稿失敗,但希望未失:)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Deconstructing a New Yorker profile

The summer of 2011 was a special one. For the first time, I got paid to work in New York City, albeit as a lowly intern. It was also the first time I picked up an issue of the New Yorker. That particular issue, published on July 25th, was remarkable. It featured Ray Dalio, the founder of the largest hedge fund in the world, Bridgewater. The piece danced gracefully between the eccentric, larger than life persona of Dalio, the unique culture at Bridgewater and the history of the hedge fund industry. The long form, descriptive and informative non-fiction style was unlike anything I have read before. I have been hooked ever since.

What makes a New Yorker profile so enthralling? Having reread a few of the profiles that I particularly enjoyed, there seems to be a few pieces to the puzzle. The first is the human character - some characters are larger than life and therefore automatically intriguing. Others are interesting because they come from more esoteric corners of the world. The second protagonist is the context. Often, there is an ongoing societal trend or issue that sweeps through an organization or a cross section of society. Often, there is a third protagonist lurking in the shadows. This is usually an idea or a theme that the writer keeps coming back to. Usually, the character and context stories have enough substance to stand on its own. However, when you add the two together, the end product is more engaging than the sum of its parts.

A piece that really captured my attention recently is Peter Hessler’s Village Voice, which follows the framework outlined above closely. In the piece, the character story is that of Rajeev Goyal, a second generation Indian American who was a Peace Corp member in Nepal and subsequently a lobbyist for the Peace Corps. His story is about grit and the unorthodox, aggressive approach that he applies to lobbying, including ambushing senators during bathroom breaks. The context / non-human story of Village Voice is that of the Peace Corps movement itself - how it all started, the peak of its popularity and its slow decline. Sandwiched between the character and the context is the idea that politics require one to be ruthless and Machiavellian. What I particularly enjoy about this style is that you are simultaneously learning about a personal story and the development of a societal trend.

In Peter Hessler’s work, as is the case in many classic New Yorker profiles, the story seamlessly moves among that of the background, the character, and the idea. Stripped down to its core, a New Yorker profile is a collection of mini stories with three interlinked foci. Given that the work is a blend of the three, the stories that the authors choose are often interrelated. For instance, in Village Voice, the stories chosen to illustrate Rajeev’s character come from his time as a Peace Corp building a water pipeline for a Nepalese community, which produces a nice segway into the Peace Corp “background” story.

This is not to say that all New Yorker profile are cookie cutter and formulaic. The magic that the contributors bring lies in how they play with a basic template and bring out different flavors. One parameter that varies greatly from article to article is the weighting of the three narratives. For instance, the Bridgewater story is heavily skewed towards that of Dalio, probably because he is a remarkable enough character on his own; in others, such as Village Voice, equal weight is given to the background and the character. Another layer of complexity is the staging of individual stories. Selecting stories, deciding upon the point of a story and balancing between providing context and getting to the point require exceptional skill. Like a blues solo, when done well, these articles are hair-raisingly moving and informative.

Since college, I have always been drawn to (or if I am being honest, jealous of) people who have great stories to tell. Those people always seem to have an endless supply of strange encounters and close calls at hand for the next conversation over a beer. I used to think that these people are just cooler than I am and are destined to run into story-worthy situations. While that is probably still somewhat true, I am starting to notice the difference that the story telling technique makes.

Further reading:

1. Alice, off the page: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/03/27/alice-off-the-page

2. Village Voice: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/12/20/village-voice

3. Mastering the Machine: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/07/25/mastering-the-machine

4. Dr. Don: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/09/26/dr-don

5. A sense of where you are: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1965/01/23/a-sense-of-where-you-are

1 note

·

View note

Text

1Q84

I first learned of Murakami through a college friend from back home. The winter of junior year, one of Murakami’s books, Norwegian Wood, was made into a movie. It was one of the few Japanese movies that made it to the screens in Hong Kong. Not having read the book beforehand, my friend brought his parents and his little sister, who had just entered secondary school, to see Norwegian Wood. Bearing the name of a famous song of The Beatles, the last thing that my friend expected was a sexually charged drama among a woman who is psychologically unstable, a friend of hers and Watanabe, the protagonist. As the characters started stripping on screen, I could only imagine the terror rumbling through my friend’s mind.

1Q84 promised to be different, at least based on its cover. In this thinly veiled tribute to or word play on George Orwell’s original, Murakami concocted a story that brought together elements of the literary world, cults, a parallel universe and murder. It all began with Aomame, a masseuse and part time hit-woman, stumbling through a hit job realising that the world around her is familiar, but strange in particular ways. In parallel, Tengo, a budding novelist, ghostwrote Air Chrysalis for the runaway daughter of a secretive cult to great popular success. Yet, he too, slowly realises that something in the dark is pulling him into a strange world.

Sounds reasonably family friendly, right?

As I innocently flipped through the book, I was ambushed in the middle of Chapter 2. Aomame just finished her hit job and is having a drink at the bar to unwind. Out of nowhere, she ends up on a one-night stand with a stranger. Similarly, in a subsequent chapter, Tengo works hard rewriting Air Chrysalis, painstakingly illustrating the imaginary world with two moons in the sky. Just as the reader is beginning to come to terms with the Little People and the dead goat, the book turns into an elaborate description of Tengo’s sex life with a married woman. These abrupt sex scenes littered the book. It is as if Murakami has a little sex alarm clock on his desk as he writes reminding him to sprinkle a healthy dose of sex into the plot every 30 to 40 pages. While certainly eye catching, these little episodes are distractions to the main story. The plot would still have made sense without any of the sex scenes. I understand that fiction is a completely different genre from magazine feature stories, which are more selective about what they leave on the page. However, in this case, Murakami probably pushed a bit too far in the other direction. It also raises disturbing questions about why he is so obsessed with these often outlandish sex scenes.

That said, Murakami displayed real craftsmanship throughout the book. The chapters alternating between Aomame and Tengo’s perspectives worked wonders in terms of framing the story. While by no means an original approach, 1Q84 aptly outlined the character, physical appearance and mannerisms of the main characters. The reader takes away from the book vivid images of each of these characters even though they only lived on paper. The first half of the book is particularly skillful in terms of managing the tempo of the plot. As the two seemingly unrelated stories run ever closer to each other, the reader can’t help but feel that something important is about to happen on the next page. This certainly kept me reading well into the night for a while. For a whopping 500 pager, 1Q84 is a surprisingly easy read.

Japanese fiction and drama have always been fascinating for me, not so much because of the often strange plots, but because of the Japanese psychology and mindset that they indirectly reveal. For instance, at first I found Murakami to be a bit of a show off when he starts referencing seemingly obscure pieces of classical music or exotic foreign brands of alcohol. However, I slowly came to realise that there is something uniquely Japanese about this. The fixation of this country on all things western, while at the same time being one of the most inward facing Asian countries, is distinctly Japanese. Perhaps Murakami’s taste for sexual encounters and extra-marital affairs also bear some Japanese DNA. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly what I learned about the Japanese psyche through the book, but every time I read a Japanese novel or watch a Japanese TV show, I sense that I am digging a little deeper into this opaque world.

What is 1Q84? Who are the Little people? Murakami creates as many new questions as he answers in this fantastical tale. While the plot does not always make sense, it was certainly an enjoyable read.

“Ho ho,” says the keeper of the beat.

“Ho ho,” the six other Little people joined in.

0 notes

Text

An unstoppable crescendo

Commuting is boring. Transporting my brain from one physical location to another requires little mental effort, and is in my opinion a waste of time. In college, I entertained myself with the news. Every morning, with my newspaper spread out in front of me, I would walk to work or school while keeping an eye on the traffic on auto pilot. News, road, news, road, news again. After graduating into the real world, my alarm is calibrated so precisely for sleep maximization that I can scarcely afford strolling to work. Audio makes much more sense for someone sprinting down the tube. For the better part of the last few years, this meant listening to my carefully curated Spotify playlist. However, I increasingly find podcasts to be a compelling alternative.

I am not alone. Indeed, podcasts are making a comeback. The number of monthly podcast listeners has grown to 75 million from 25 million [article here]. Shows range in length, but are usually 30 minute to an hour long. The most common podcast format is the interview. The other dominant format is the season long story. This includes shows like Serial or Start Up, telling a story across multiple episodes. There is no shortage of good material for both formats (see end of the article for my favorites).

Podcasts have the same target audience as radio. People spend a lot of time on the road. Since visual content cannot be consumed while driving, most listen to the radio. A number that is repeatedly quoted is that traditional radio reaches around 240 million people a year. That said, radio has obvious shortcomings, such as not being to provide on-demand content, limited geographical reach etc. Podcasts are especially well placed to solve the on-demand aspect of the equation. I, for one, would never adjust my sleep schedule for a show. By taking advantage of the proliferation of cell phones and new platforms such as the podcast app on iPhones, podcasts are on the verge of becoming major competition of mainstream radio.

There are a few shows that have huge followings, but also a long tail of podcasts that only have a small following. According to this article here, having 9000 listeners downloads per episode puts a podcast in the top 5% of all podcasts, while having 50,000 listeners will put it in the 1%. These numbers pale in comparison to those of TV and radio, but are growing rapidly.

Most podcasts are ad-supported, and could be a profitable, though not life-changingly lucrative venture. One thing that advertisers and podcast producers keep talking about is native advertising. The hypothesis is that because the podcast host, whom listeners are familiar with, is reading the ad, listeners are more likely to respond. In terms of numbers, podcasts seem to be able to command ~$20 per CPM (revenue per thousand impressions / listens, source here). Given that each podcast usually average 3 ads, we can estimate the total revenue of a reasonably popular podcast as follows:

top 5 percentile: 3 x 10,000 listeners / 1000 x 20 = 600 per episode

top 1 percentile: 3 x 50,000 listeners / 1000 x 20 = 3,000 per episode

Some shows, like WTF with Marc Maron, are a little more liberal with their ads and could run five to six ads per episode, which further improves the economics. Most of the popular shows average a show a week or every two weeks. For someone running around with a mic interviewing people, probably for free, with little overhead, the numbers are actually not bad. That said, a significant portion of podcasts currently do not have advertising. However, if podcasts continue their meteoric rise, the ones with listeners should have no problem finding advertising dollars.

Estimated annual pay (1 show per week)

top 5 percentile: 600 * 52 = 31,200

top 1 percentile: 3000*52 = 156,000

Even as a disruptor of radio, the podcast industry is not a static medium. There will likely be significant changes to the technology, revenue sources and business model as podcasts moves from being made in garages to the professional media world.

The headline CPM rate will likely go down. Currently CPMs are measured based on download, rather than true statistics on number of listeners. Given that most podcast software download new podcasts automatically, the audience figures for many shows are inflated for sure. In the medium run, advertisers will want to switch to paying for real listeners, rather than downloads. As players like spotify step into the game, moving podcasts away from MP3 based technology, advertisers will become more selective in what statistic they pay for.

The discovery process will become easier, with a few apps serving as cross podcast platforms and providing curation services. Currently, since podcast producers are usually independent of each other, it is often difficult to discover good podcasts. There is room for a “Goodreads of podcasts” that takes care of curation. In my opinion, services like spotify are well placed to provide recommendations and a “TV channel” like platform for podcasts in a centralized application. Apple, with its podcast app, addresses the platform part of the question, but should do much more on the curation / recommendation front. Once there is enough traffic on the platform, there are all sorts of opportunities to monetize the user base.

One way for platforms to monetize their position would be to provide gated, listener paid-for content. Gimlet Media, founded by the former producer of This American Life Alex Blumberg, appears to be heading this way. Gimlet produces multiple podcasts (notably Start Up, which is a podcast about starting Gimlet). Based on the few episodes that I have heard, Gimlet’s end game appears to be a “freemium” type model for podcasts, whereby some content will be free, serving as teasers for gated premium episodes. However, my hypothesis is that a platform is in a better position to offer a freemium because it can offer a more seamless user experience, control how much users listen to a given podcast, take care of ad placement and have access to more detailed user data.

Lastly, there is a lot of scope for podcast hosts to put on offline events. Live, recorded shows offer extra ticket income and reinforces the hosts’ relationship with listeners in addition to regular advertising income from downloaded podcasts. For example, Death, Sex and Money had a sold out anniversary event at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Marc Maron from WTF regularly hosts live shows. Going forward, I expect more podcast hosts to branch out to other distribution channels outside of audio, and vice versa.

The future of podcasts is bright.

Here are some that I enjoy:

Longform: Wonderful podcast interviewing different journalists, with a bias towards magazine editors and feature writers. Some of my favorite interviewees include Michael Lewis, Adam Higginbotham, and Jake Halpern. This show really opened my eyes to the journalism world. My favorite show.

Death, sex and money with Anna Sale: Covers exactly what the title suggests. Every episode, Anna Sale interviews characters about one of the topics. For me, this show reinforces my view that Americans are really open to sharing their lives with strangers, even on the airwaves. Some good episodes include Ken Jeong’s relationship with his wife, an interview with an ex NFL player who’s now in business school. Really honest discussions about things that we don’t usually talk about out loud, but are all thinking about in our heads. Only danger to listening to this show is that you might start asking questions in Anna Sale’s voice (“so how do you deal with fear?”) too often and lose all your friends.

Londongigguide: London is fabulous for live indie gigs for cheap. I get all my gig information here, and the music is simply incredible.

Strangers with Lea Thau: You might have heard of the story telling organisation called “The Moth”. Lea Thau ran that for a while, but is now doing this podcast instead. One of the episodes was about this man who wants to put Lea’s baby’s poop into his intestines. Worry not, however, the other shows are safe for work and are very fun

Serial by Sarah Koenig: The closest thing there is to a TV show on audio. The show investigated the murder of Have Min Lee in 1999. Massively successful, Koenig interviews friends, lawyers, police investigators and the alleged murderer who is now in jail. Serial is so successful that producers decided to go ahead with Series 2 and 3, to be released later this year

Hot pod by Nick Quah: Not a podcast, but a newsletter about the podcast industry. This guy is only a few years out of college, but has quickly established himself as one of the few commentators of the podcast industry

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Writing - Stephen King

I used to read fiction as a kid. My favorite was a translated version of Robinson Crusoe. The cover of the book was black, covered with a plastic-ky gloss, and had a thumbnail picture of Crusoe on it. I remember coming home from school and lying in bed reading under the sticky summer afternoons in Hong Kong. I probably read it for more than 10 times.

Strangely though, I don’t recall that much of the plot. All I remember is Crusoe somehow getting stranded on an island, building a canoe which he couldn’t move, acquiring a slave Friday, and eventually making it back to England. I have always found this inability of recollect stories frustrating. To me, reading fiction is a bit like sleeping. I would come out at the end of the book feeling like I just teleported back from an alien world, remembering only bits and pieces of what happened. Often, I could recall the mood of the ending, but not the actual plot. To me, reading fiction seems more like consumption than investment, and so after a while I became a non-fiction only reader.

Naturally, I was a little hesitant to pick up On Writing by Stephen King, a famous fiction writer. I knew very little about King, except that there is always a full shelf of his books in stores. I did know that he wrote The Shining and many other horror books. In the back of my mind I pictured him as an old man that wore small gold-rimmed glasses halfway down the ridge of his nose, collected dead bodies of animals and had a black cat with yellow eyes.

King opened the book with the chapter CV, describing his upbringing in a working class family in Maine. King was a bit of a troublemaker at school, but had a genuine gift with his pen and a passion for short stories and horror movies. His writing was not an immediate success. After he finished college, he worked at a laundromat for a few years and started teaching at a school, while relentlessly writing at night. Eventually, after countless rejections, he got his first major break with the book Carrie. Not that exciting of a story for someone making a living off fantasy stories, no?

What I found particularly striking, however, was the way he threaded together his experiences (which while far from being boring, wasn’t terribly exceptional) into a captivating read. He kept the language informal and often mixed in vivid imagery and dialogue. My favorite part was his description of doctors puncturing his ear drum as a kid. It read so smoothly that it almost felt like King was telling you about his life casually over dinner. I blew through a third of the book in the first sitting. His writing illustrates that there is middle ground between outright dictation of everyday speech (as in waitbutwhy) and more descriptive, verbose styles such as that in Lord of the Rings. King’s style is not unlike Tim Geithner’s in Stress Test, but more refined and less matter of fact. It is definitely one that I would like to imitate.

My other major takeaway from the book is that there is a lot that non-fiction writers can learn from their counterparts in fiction. Like it or not, a lot of non-fiction can be really dry and esoteric. Publications like the FT can be captivating for finance nerds, but they don’t speak to a wide audience. Stories offer a way out. Humans are more likely to relate with narratives than dry facts and derivations. Having finished On Writing, I came to realize that a lot of non-fiction writing that I enjoyed, such as Hiroshima on the New Yorker and The Emperor of All Maladies, leveraged a lot of the same techniques that fiction writers employ, such as dialogue and character building. On the contrary, most SeekingAlpha articles, while intellectually interesting, are hidden behind a cloudy wall in my head and impenetrable for outsiders. Looking back at some of my previous work here on streamsmith, I realize that many of my pieces, such as “Stepping out of the shadows of umbrellas”, could have been much stronger if I had invested the time to present the message around a story or character. King masterfully (he strongly disapproves of adverbs) demonstrated why he is one of the world’s foremost fiction writers. The second half of his book on actual writing advice was solid, but the first half on his personal story was an even more impressive demonstration of what good story writing is like. If you want to become a better writer, but have trouble staying awake while flipping through The Elements of Style, look no further than On Writing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The price of being a word flower

It is almost cliché thesedays to talk about the decline of print media in the wake of the financialcrisis. Print readership dropped precipitously, along with advertising revenue. When even mainstream publications such as the Atlantic struggle, one could only imagine the plight of publications that have a more artsy focus and a more niche audience.

However, as the eulogy for Anglo Saxon print publication continued, Chinese publications seem to be frozen in time. By and large, the major print newspapers and magazines are still offline, with only halfhearted attempts at going online. Yet, while the mass market publications (e.g., daily newspapers) could afford to keep their calm, what was unveiled this week at zi hua (字花, which literally means word flower) was a shot across the bow for all Chinese media, new and old.

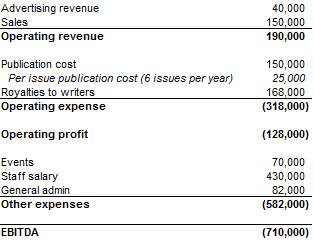

Zi hua is a small literary magazine that aims to promote Chinese literature, with an audience mostly within the academic and literary circles in Hong Kong. As with most small magazines that are private, information on its circulation and financial health are hard to come by. However, in a rare spat with one of its contributors this week, Zi hua’s management decided to release its P&L to the public for the first time:

(Table 1: Zi hua P&L 2014 - All figures in HKD)

As table 1 demonstrates, Zi hua is basically a charity. It is deeply unprofitable and would likely cease to operate immediately without government subsidies plugging the gap. To make matters worse, the price of each Zi hua copy sold is insufficient to cover its variable costs. By severelyadverse’s analysis, zi hua would have to almost double its price (from 45 HKD to ~90 HKD or 12 USD) just to cover its per unit variable costs.

While artistic / literary magazines do play an important role in educating the public, there are obvious disadvantages to being deep in the red year after year. First of all, the lack of financial success will likely jeopardize the publication’s ability to fulfill its social mission in the long run. Secondly, even if men do not live on bread alone, the lack of financial resources will likely make it more difficult to attract top talent into the organization or the field.

What could be done to bring magazines like Zi hua closer to the line? Apart from the suicidal magazine pricing, the royalties, salary and other expenses incurred by the 5-person outfit hardly seem extravagant. In fact, with the chief editor being paid a meager 15,000 USD a year, much of the cost structure already seem bare boned. Like all good things in life, the solution to zi hua’s pricing likely comes in three parts: pricing, digitalization and broadening of target audience

1. Pricing: If the magazine’s pricing does not even cover its per unit variable cost, every additional copy sold will be pushing the magazine deeper into the quicksand. This doesn’t mean that magazines like zi hua would need to double or triple their pricing. With the help of digitalization, zi hua might only have to raise its prices by ~1 USD to breakeven

2. Digitalization: For publications that could not take advantage of economies of scale due to a small circulation, this should hardly be a surprise. Zi hua currently does have an iphone app, but comments on apple store indicate that the app is barely functional

a. Unit economics: While the marginal cost to physically printing a copy of Zi hua is 45 HKD (excluding royalties, events), the marginal cost of digitally distributing copies is essentially zero. Based on severelyadverse’s estimates, this could cut the cost per issue (including publishing, royalties and events) by ~45% and allow the magazine to at least cover its variable costs b. Evolving reader preferences: Judging from the activities and events that Zi hua hosts, its primary target audience is students or young adults. Given this segment’s propensity to internet / mobile based solutions, it should be relatively easy to usher them online compared to seventy year old grandpas c. Data collection: Having an online interface will also (theoretically) allow zi hua to gain a better understanding of the reader demographic and successes of different content

3. Broadening of target audience: Another direction that the magazine could take is to broaden its target audience, which would increase the publication’s advertising and subscription revenue. One way to achieve this is through the broadening of the magazine’s reach to other markets in the region. Given that Chinese is the language shared by other populations in the region such as China, Taiwan and parts of Malaysia, there is little reason to limiting a Chinese literature magazine’s focus to a city that has less than 1% of the language’s native speakers

The print media industry in Chinese speaking Asia (particularly books and magazines) is in stone age in terms of its distribution model and content breadth. If the experience of publications such as the New York Times or the Atlantic is any guide, much of Chinese print media is still standing on shaky foundations. With the help of digitalization and small doses of restructuring, small print publications like zi hua might be able to live up to its big dreams in a more sustainable way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Stepping out of the shadows of umbrellas

[Timelapse] Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong from Chris Yiu on Vimeo.

The revolution didn’t happen overnight. Under pressure from skyrocketing prices amidst stagnant wages, simmering relations with their kin from mainland China and the lack of social mobility, the relationship between the after 80s and the government has been a rocky one for the last decade. The government has been trying a mix of policies to address some of the issues, such as restrictions on property speculation, etc. However, these efforts were largely unsuccessful, and have been further undermined by the government’s own PR disaster. As the government is seen as lacking legitimacy and being in bed with big businesses, it has had a very difficult time getting policies through the Legislative Council, the semi democratic legislative branch of the government. Routine policy discussions inevitably turned into filibusters or referendums on the government. The resultant legislative deadlock in turn reinforced the government’s perceived incompetence and lack of legitimacy. As social problems remain unresolved, social angst bubbled into a boil.

The Umbrella Revolutionaries have taken a hardline on the right issues – to reduce the democratic deficit of the government. However, to insist on the exact manifestation of this ideal – full universal suffrage, would be a mistake. In this struggle for democracy, the “revolutionaries” are going up against the ruling party of China. Beijing’s deepest fear is the emergence of a political entity that would challenge its legitimacy. Unless people in Hong Kong are ready to shed some serious blood and take up arms, it is unrealistic to expect the party to cave on its number one fear. While sticking it to the party and asking for the things that everybody knows cannot be granted may sound quixotic and valiant, it does not take Hong Kong any closer to resolving its immediate or long term problems.

The revolutionaries should take advantage of the momentum built up from the streets to push through serious democratic reforms, while being sensitive to the bottom line of Beijing. There are many ways of enhancing the democratic credentials of the government apart from universal suffrage. For instance, abolishing or phasing out functional groups (representatives for businesses and professional groups often blamed for leaning too much towards big businesses) from the LegCo is a concrete step in the right direction. Other options include increasing the percentage of representatives directly elected into the Chief Executive election committee. Compared to universal suffrage, all these measures add to the democratic credentials of the government, without stoking Beijing’s deepest fears.

In the short term, the first thing that the revolutionaries should do is to slowly shift its stance away from the previous hardline that it struck. Currently, the crowds camping out in Admiralty have their minds fixated on universal suffrage. The revolutionaries need to slowly introduce other options on the table and instill the idea that there is more than one way to “win”. On the government’s end, Beijing and the Chief Executive need to be prepared to make concrete compromises where they can. Continuing to shun the students risks magnifying the democratic deficit of the government and reinforcing the notion that it is all or nothing for the sect vying for more democracy in Hong Kong. In the medium term, the government needs to take serious measure against the socio economic problems that are breaking the backs of Hong Kongers and overhaul its image. However, these are not even on the table unless the government solves its immediate political crisis.

The revolution has stoked the political flames long dormant in the hearts of Hong Kongers. The peaceful expression of the movement’s ideals and the community that it has built on the concrete roads of Admiralty are testament to the zeal and civility of the revolutionaries. However, while standing under the protection of the umbrella is comforting, the time might have come for the movement to start getting their feet wet and grappling with the ugly monster that is reality.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Fab Five and the Triumph of Individualism

ESPN documentary "The Fab Five" tells the story of Michigan's vaunted underclassman starting five in 1991 and 1992, but also presents a canonical example of successful self-expression in the business world.

Michigan's Fab Five -- Chris Webber, Jalen Rose, Juwan Howard, Jimmy King, Ray Jackson, were controversial on the court for subverting several college basketball trends. For one, they were basketball fashionistas. Though no modern NBA player or fan would bat an eye today at their sartorial choices, the Fab Five's were considered iconoclasts when they adopted baggy shorts* and long black socks (not to mention shaved heads) as opposed to the short shorts and white socks worn by their basketball forefathers.

The Fab Five also rocked the college basketball world by inverting the pyramid of power governing the college game up until the 90s. While modern day NCAA is nothing but legions of upperclassman supporting its one and done freshman stars, the idea that the freshman of the team could be more talented than the seniors was completely foreign at the time. To punctuate all this, the Fab Five played with an "urban" attitude never before seen in college hoops. They flashed no-look passes and soaring dunks, all while pioneering the art and craft of staredowns and trash-talking as psychological weapons. In a game that had accepted the quote-unquote assimilated African American player (think Grant Hill, whom Jalen Rose is quoted to have envied deeply for having a normal family), the Michigan team of the Fab Five directly repudiated of the concept of the player -- well-mannered and well-behaved -- that they were supposed to be.

The Fab Five documentary suggests that concern with traditional decorum is often swift, unforgiving, and overblown. Michigan alumni, for example, responded to the Fab Five flair with letters lambasting the group for being disrespectful "negroes" who were on the brink of breaking college basketball as they knew it. The racist sentiment, however vehement at first, was overtaken by the Fab Five's popular appeal stemming from the return of Michigan basketball to relevance and excellence. In fact, the reason why their actions took on a larger significance and spurred such debate was because the team received national attention due to its rankings and was able to back up its swagger with substantial basketball skill. In alternate universe where the Fab Five failed to revitalize basketball, I struggle to see them being described as more than a group of quirky individuals in the annals of basketball history.

And so, the Fab Five story played out on the courts, but also happens to be prescriptive about self-expression in other professional settings, including business. At its core, the story is really about how one plays a game, and the "game" of business, I'd argue, is not so different from the game of basketball - it involves a goal (whether revenue, profits, or margins) and sets of rules and regulations (e.g., don't commit fraud) that are agreed to by the participants. Outside these constraints, the only thing that matters in the long-term is success in achieving the goal. Other cultural niceties -- dress, language, customs -- are merely social constructs. You (blue-chip company, white, male CEO, Grant Hill) can abide by them and succeed...but you (start-up, minority/woman CEO, Fab Five member) can also disregard them completely and still succeed. One thread ties this second group of individuals together -- they stopped worrying constantly about how they fit into someone else's idea, and instead, focused on makes them Fab.

*The Illini claim to have pioneered the long shorts concept...the fact that no one really care about this story merely illustrates how winners get to write history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apes as art critics (1889)

As I stepped out of the Odeonplatz station, Munich was filled to the brim with euphoria. Men in lederhosens laid motionless on the ground, foaming at the mouth, while their equally intoxicated companions laughed on. Half of them sounded American. Munich during Oktoberfest is where tradition meets debauchery and capitalism. Even though I don’t drink, I couldn’t help but feel Munich’s rowdiness and cheerfulness slowly getting up to my head.

As beers were being downed and the chants of Ein Prosit grew louder, I was walking up the steps of the Neue Pinakothek, the Art Museum in Munich. I felt a bit like a tourist in New York going to MoMa to see Starry Night – something that you do just to tell people that you’ve done it. For the artistically challenged data grunt that I am, my expectations for paintings from dead people couldn’t have been any lower.

For an art museum, the Pinakothek is a surprisingly non-descript building, with none of the grand architecture that you see at the MoMa or the National Gallery. Yet, pushing through the doors by the reception, I was immediately struck by the space in the museum. Perhaps it’s because everyone is busying drinking beer, there were only a few patrons in the museum. Strolling past the ticketing desk, the silence was deafening. On the brightly lit walls, the sparsely hung paintings reinforced the minimalist feel of the museum. Looking at the paintings with no one else around, I felt like I was entering a trance with a slide show of landscapes and scenes.

Stopping for a brief moment in a room upstairs on the east side of the second floor, I found myself in front of the self portrait of Albrecht Durer. I had seen the Jesus-looking painting from a book cover, but didn't think much about it until I saw the original. The lively eyes on the painting appeared to be looking straight at me, no matter how I moved in front of it. I was not sure whether there is any deep meaning behind the painting, but the moment my eyes hit the painting, I was immediately struck by the self-assured, calm air oozing out of the figure.

Albrecht Durer (1500), Self-portrait at 28

Portraits like these and older paintings have always seemed more engaging and relatable to me. In contrast, I find a large part of what people call “contemporary art” incredibly difficult to understand. A friend of mine argued that the transition in style is at least in part due to the advent of the camera, which destroyed the need for the “older” / more realistic types of art. Staring at Durer’s face, I began to have some doubts about this theory. For portraits, I could somewhat see why technology had displaced the need for realistic portraiture. Yet, while photographs provide an unsurpassable degree of realism, paintings offer other features. For instance, a buyer of a Monet Impressionist work is probably looking not for realism, but for other qualities such as the loose brush strokes, the specific ambience and bright colors. In addition, while photographs are largely limited to what could happen in the real world, paintings offer the viewer a chance to see the impossible (see the Rottman work below). All this suggests that photographs are not functionally perfect substitutes of paintings. While I could understand why works that stress realism such as portraits were displaced by photographs, the (seemingly) general trend towards less interpretable forms of expression seems to have a different cause.

But what do I know?

Walking around a museum is a challenge in its own right for my (poor) fitness. Sitting down briefly for a break, I found myself face to face with a series of paintings by Carl Rottmann on landscapes that juxtapose myth with reality. In the room lined with bronze tiles, large paintings of Marathon, Corinth and Olympia hung in silence. A small figure of Pheidippides was running back from Battle against the expansive landscape. The intricate features and the texture of the painting were truly striking. As I looked up to the paintings intentionally hung on tall walls, the sheer sizes of the paintings were also impressive. I saw the same paintings afterwards in the book shop, but print / digital versions of paintings just don’t do the job.

Carl Rottmann (1848), Marathon

After posing pretentiously for an obligatory tourist pic, I dragged myself into the next gallery. Mindlessly drifting from painting to painting, I stumbled upon many paintings that made no impression at all but also quite a few that are truly interesting. The artistic technicality of most pieces was a complete mystery to me, but what often left a mark was the story behind the paintings. Take, for example, Monet and Manet’s works on the Seine. Similar scenes have been painted to death by countless impressionist painters. However, what made these two interesting was the history behind it. Apparently, Monet and Manet were painting together that day, and they just painted each other en plein air. All of a sudden, I seemed to be able to get pass the jargon and brush strokes and somewhat grasp loosely the idea that is being conveyed and see the characters of the painting.

Edouard Manet (1874), Monet painting on the Seine

Stepping out of the exhibit into the bookshop, I could scarcely believe how much I enjoyed the visit. As I flipped through one of the giant coffee table art books, I recognized almost none of the jargon in it, but recalled vividly some of the imagery and the stories behind them. Perhaps my ignorance is bliss; perhaps I am just like one of the cheerful protagonists of my favorite painting of the day:

Apes as art critics. Gabriel von Max (1889)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Rickshaw Boy – Lao she (駱駝祥子 – 老舍)

Maybe it is the pressure from work and the long hours, but recently I have found it quite impossible to read any serious non-fiction outside of work. An earlier attempt at Lawrence in Arabia ended up being one of the best naps I have had since moving to London. I knew that I needed something different.

That’s when I turned to The Rickshaw Boy, a modern Chinese classic by Lao she written in the 1950s after the Communist Party took power. The book unfolded with Xiang zi (祥子), an illiterate, destitute rickshaw puller arriving in Beijing at a time when China was divided by various warlords during the power vacuum after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. Xiang zi was an honest, hardworking puller obsessed with sustaining himself and owning his own rickshaw. He did get to have his own rickshaw for a short while, only for the warlords to capture him as free labor and striping him of everything. While he managed to escape from the POW life later on, bad luck never seemed to be too far behind. He gets tricked into marriage with a woman he didn't love, blackmailed by the warlords and was bed stricken by diseases from overworking. Eventually, it dawned on Xiang zi that honesty and hardwork just won’t do. The book closes with him becoming a through and through crook eking out a living with all his attention on living through the day.

In many ways, the story of Xiang zi could have followed the mold of the American dream – a self-made man who starts out with nothing, but succeeds through sheer grit and honest hard work. However, Xiang zi’s story seems to demonstrate the exact opposite. No matter how hard he tried, fate and the greed of others constantly bogged down the honest entrepreneur. What’s even more heart wrenching is that many of the obstacles facing Xiang zi seem entirely believable on their own. Under Lao She’s descriptive yet fluid prose, Xiang zi and his little rickshaw leapt to life.

My takeaway from the Rickshaw Boy is that perhaps individualistic honest hardwork and character are not enough. Even for people with those qualities, being in the right environment where honest hardwork is valued is absolutely indispensable. As Xiang zi’s story demonstrates, a society in that is everyone for themselves yet unmediated by kindness and the right ethos could turn people with the best intentions into the most cynical thug.

This then begs the question – what would I have done if I were Xiang zi? You couldn’t live in the status quo, but the only way to comfort is by turning into a dog in a dog eat dog world. Sitting in my comfortable room in Clerkenwell, my immediate reaction is to say that Xiang zi should have stayed the course instead of selling out to the realities of the world. However, deep down, a small piece of me also suspects that as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance1. Perhaps I really can’t say what my answer will be until sh*t hits the fan.