Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Straw Bale Construction Manual

by Benjamin Krick and Gernot Minke

Here's another book I found very intriguing but (after getting it via interlibrary loan) decided I wouldn't recommend.

This book is written by a german author, which I blatantly stereotyped into assuming would make it more technically rigorous than the books I've already read. I was also intrigued by how things might be done differently in Europe.

Overall, the English translation was clumsy (could have used proofreading by someone who's familiar with the english-speaking strawbale scene because many terms were used differently) and the things that were unfamiliar were unapplicable. The translation is from 2020 but the book itself is from 2015 and only references the New Mexico building codes. There were several references to things I consider dubious - putting bales in roofs/floors, steel pinning of bales, using steel plates to anchor bales to the framing. The actual sections on construction were pretty short and the technical stuff overlapped with things I'd already read.

Good things about the book/my takeaways:

The idea of making a bent, two pronged baling needle for resizing bales was intriguing. Definitely worth a shot.

Lots of discussion of using jacks or ratchet straps to pre-tension your walls before placing the last course, further evidence that it can be done.

An interesting discussion of the german/european strawbale building scene

Another vote in favor of using stabilized earth plaster; makes the reasonable point that the silane coatings that can be applied over earth plaster are fragile.

Lots of discussion of rain screening, I'm curious if that's a regulatory directed push or a climate one.

1 note

·

View note

Text

book notes: How Buildings Learn

by Stewart Brand

This book was recommended in Serious Strawbale and the concept was very intriguing to me, so I finally requested it via interlibrary loan. And now I am here to save you the trouble!

How Buildings Learn is mainly an investigation of commercial and institutional buildings & how architects fail to deliver on buildings that work for their inhabitants*. There's very little on residential structures in here and I can probably summarize most of it for you right now:

Don't follow trends because they go out of date.

Make the services of your building (wiring, HVAC, etc.) as accessible as possible.

If you do not plan a space for "low road" space storage and services, one will be planned for you. Attics, basements, sheds, garages...something is going to be taken over so plan for it.

Flat roofs suck.

When designing a house, contemplate various scenarios and how the building would work in those scenarios. (Two people living alone: What if there were children? What if your parents moved in? What if you started working from home? What if you took up woodworking? etc)

Go Read Chris Alexander's A Pattern Language (which comes up at least once a chapter, Mr. Brand is in love with this book)

*On the subject of architects, if you're curious, his claim is basically that fragmentation of the building industry such that most of the important elements of a building's interior/services/engineering are handled by outside parties gives the architect only one realm to win awards and be recognized: doing things that look cool in magazines. This is, obviously, mainly a critique of commercial/institutional architects.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

book notes: Musings of an Energy Nerd

by Martin Holladay

This book is a collection of essays by Martin Holladay originally posted on the Green Building Advisor website. It acts as a general overview of energy efficiency topics & also a preview of his articles there. I think I'm definitely intrigued enough to subscribe for a month at some point (when I have fewer books out from the library!) and read more of his articles on topics I still feel undereducated in.

Now, Mr. Holladay is not into natural building, he's into energy efficient building. He's not about using local/natural materials and I don't think he's very impressed by straw bale construction. nonetheless, a lot of the advice is applicable to natural building projects bc physics works the same everywhere.

The book is a solid intro on:

Air sealing buildings

Basements :D

Insulated ceilings

Basic HVAC decision making

Pros/cons for cost effective green building

Things I learned about/want to follow up on:

Pros/cons of HRV vs exhaust only vs intake only ventilation. For cost reasons (and avoiding ductwork!) I'm really starting to think about exhaust only ventilation. I need to follow up on passive vents and whether they can be used effectively.

Drainpipe heat recovery devices - recover heat from the hot water being used in showers to heat up incoming water! A reasonably low cost investment with a reasonable return if the design works to have a vertical drainpipe down from the shower (potential with a basement).

How to properly insulate an attic if it's site-built instead of build with trusses. If the rafters come down to nothing at the corners of the wall there won't be sufficient space for insulation 🤔 should the walls be raised up slightly over the level of the ceiling?

Testing air sealing via theatrical fog machines (and obviously blower doors) - I'm not sure when in the process you should test a strawbale house. Presumably after the first coat of plaster on the interior and exterior? After which point fixing things will be a pain so DETAIL AIR SEALING PROPERLY

Using a small mini-split system (with only one or two units) to heat/cool a 1 story house seems to be plausible and lower cost than most of the alternatives. While I think I could live without air conditioning, it does have the benefit of decreasing humidity in the house.

1 note

·

View note

Text

book notes: Building with Lime; A Practical Introduction

by Stafford Holmes and Michael Wingate

This book had shown up in recommended reading lists of several other natural building books I read; it's basically the first book of the lime revival, attempting to put into writing a lot of older cultural knowledge.

I read most of this book, and then went and referenced all the other plastering books I could fine and just read through their lime plaster sections to get a good grounding on the topic. Here's my overall takeaways.

The good:

This book is extremely detail oriented. It's basically a textbook. It has an authoritative, fact-based intro which really helped me finally comprehend the difference between the types of limes. The combined powers of lots of internet quasi-experts had managed to confuse the hell out of me on this topic.

There are tons of illustrations, which are all great

If you're curious about any aspect of lime building, it's in here. Plaster? Mortar? Limewashes? Decorative plaster elements? Lining canals? Assessing limestone you found in a field for kilning and turning into lime? It's all in here

The less-good (for my purposes):

The book is very British. The terms used for types of limes and tools and plaster coats are all different than I'm used to as an American.

On that same note - this book is of the opinion the only acceptable limes for plastering are lime putty, quicklime or hydraulic lime. From my American-sourced reading, our S-type hydrated lime is fine to use as a plaster (if not quite as good as a putty type lime) and is vastly superior to the bagged hydrated limes they sell in the UK. The cost difference in using hydrated lime vs putty/hydraulic would be enough to make me hesitate on using lime at all.

The book didn't include guidance on the one topic I was most curious about - drying times and how to avoid burn marks/seams if you're plastering a large surface with a smaller team than can finish in a day.

This book is very much about how to do fine lime finishes. The assumption is that you want a traditional finish done to the best of historic restoration standards

I think my overall takeaway from this book is that I'm leaning harder towards a clay plaster finish, inside and out. Clay plaster is cheaper, easier to work with, and infinitely workable so you don't have to race the clock to get your plaster finished. It's also much less weather resistant, obviously, but I think with a silica paint/waterglass top coat it could work fine. Maybe even with a limewash overtop?

I am still very confused why limewashes over clay plasters are apparently acceptable but lime plaster over clay plaster is not. Makes my head hurt.

I would still (probably) like to use a lime plaster over my exposed foundation; I'm envisioning exterior insulation so a protective plaster topcoat of some sort will be needful. I kinda like the idea of embedding rocks/pebbles in the foundation plaster.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I went through a bunch of the bungalow books today and pulled out some designs that felt modifiable into something that'd fit my needs. I (of course) forgot to write down what year each one came from (whoops).

Here's my vague thoughts on tetris-ing these plans:

Plan 210 - Make stairs a straight shot from living room, widen kitchen so it can have U-shaped design. Move bathroom beside kitchen and cannibalize bedroom #3 to expand out bedroom #2 and make a washer/dryer nook.

Design 248 - Tetris time again XD. Cut off some of the with of the house on the right, remove the top right bedroom, and expand out the other bedroom to fill this pace. Swap the stairs into the living room, and split the space to widen the kitchen and bathroom. Invert the kitchen so the prep is towards the inside of the house and the dining is on the outer wall.

Design 242 - Put the staircase on the living room side, then move the kitchen down. Swap the kitchen around so the eating area is beside the main window. Cannibalize bedroom #3 to widen bedroom #2 and the bathroom, then use the remaining space as a utility/laundry area.

Design 244 - Square off the design, narrowing the two bedrooms, then merge the two rooms. Move the stairs over into the living space instead of the kitchen space. Not sure where I'd go after that but this design intrigues me.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation - Small House Designs

If you've got a hankering to look at small home designs for inspiration, and you've got a preference for older design features (rooms with walls, for instance): The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation ran a design competition in the early 1900s, and published those home plans in booklets that you can now find on Archive.org.

I really like a few things about these designs:

They're small

They bungalow designs almost all have basements

The kitchens are in separate rooms, hallelujah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation - Small House Designs

If you've got a hankering to look at small home designs for inspiration, and you've got a preference for older design features (rooms with walls, for instance): The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation ran a design competition in the early 1900s, and published those home plans in booklets that you can now find on Archive.org.

I really like a few things about these designs:

They're small

They bungalow designs almost all have basements

The kitchens are in separate rooms, hallelujah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surfin' StrawBale - Old-fashioned weblink list

A lot of old strawbale reference sites/sources died with Web 1.0. Sadly this includes a lot of the email newsletters, old webrings and social groups (most of whom seem to have migrated to Yahoo Groups and then shuttered when it died.....or moved to Facebook, which is possibly worse 😧).

But today I stumbled across a real old fashioned weblink list that's still active! It's hosted on an untouched-since-2013 page of the Masonry Heater Association's website. Maybe half of the links are since defunct, but you can use the addresses to hunt them down on the wayback machine.

Yeehaw, Strawbale!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Balewatch strawbale house plans

If you've ever been thinking about strawbale building and tried googling "straw bale house plans", you've probably gotten linked to Balewatch.com. Unfortunately, if you were searching this in the past decade, that brought you to a dead website.

I finally had the (obvious) idea to check the Wayback Machine today and found an archived copy! It looks like circa 2013, the site owner (Robert Andrews) was trying to sell the site. That didn't happen, and presumably he's either passed away or retired since - I wasn't able to find any information.

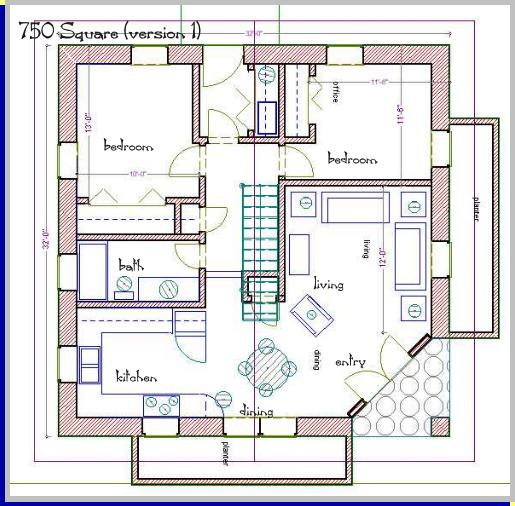

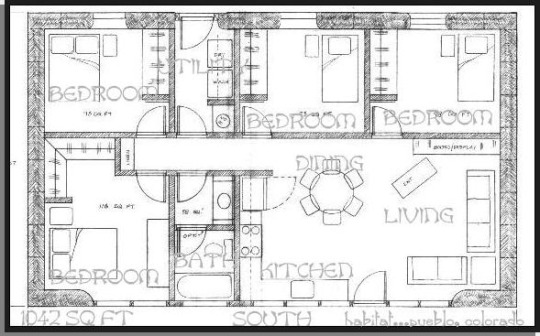

But without further ado, I wanted to look at a few of his plan sketches at you can find at the Wayback link above. The actual plans can no longer be acquired, but the sketches are still an interesting study.

He's listed the plans from smallest (140 sq ft) to largest (10,000). I'm just gonna look at a few with ideas I liked in the 700-1300 range.

(750 Square) - oh look, a plan with a basement!! the kitchen and living areas are *almost* separate, the thing I want most in life. I think this might be the most intriguing of the lot, personally, though I don't love how the dining table ends up right in the way of the stairs.

(812 Square) - here's another plan that's almost something I could use. The weirdly shaped hallway is an interesting space-saving idea, but I think it puts all the doors so close together that actual construction would be a nightmare.

(895 Spiral) I'm not saying this is a good design for the owner-builder. It isn't. But it's fun to look at.

(1042 Habitat) This plan doesn't meet any of my design criteria, and clearly has succumbed to the early-passive-solar design mistake of excessive south-facing windows. But it's a fascinating plan nonetheless. 4 bedrooms in 1000 square feet! Absolutely wild.

(1135 Ranch) Much like the plan above; I find this interesting mostly for how much he's managed to squeeze into the design, not because the arrangement would work for me. Definitely another door spacing issue in this one around the bedrooms.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strawbale home in Whidbey Island, WA; sold 2020. More pictures available here.

#straw bale construction#natural building#home#My favorite thing about this house is definitely the outside plaster - the color is gorgeous#second favorite is the patio#the detailing on the plaster throughout is impeccable#the whole house is much too large for me but otherwise? wonderful#inspiration: houses

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have looked at so many home plans that do not understand this. no i don’t want to see the TV/socialize with people in other rooms. I’m in the kitchen. This is me time.

#every single strawbale plan puts in a shared living/dining/kitchen space#i'm fine with the kitchen/dining being one room but get the living room out of there!#stop putting entryways in the kitchen!#stop facing the workspace *towards* other rooms and then putting in half-walls#i cannot tolerate people while i'm trying to concentrate on not forgetting the many essential steps of cooking#meme#this blog deserves a few memes#as a treat

60K notes

·

View notes

Text

book notes: More Straw Bale Building

by Chris Magwood, Peter Mack and Tina Therrien

With notes on Essential Sustainable Home Design by Chris Magwood

Somehow, early in my mission to read every book on strawbale construction ever published (......I’m joking. Mostly) I got the weird impression that the Chris Magwood books were not good. I have no idea where this idea came from, but I might have deprived myself forever if Andrew hadn’t thrown his name out there as a good reference source during our workshop. This book was great!

This is probably the single most comprehensive book on strawbale construction I’ve read so far. It was, like many reference books, published prior to the strawbale code going into effect, but thankfully after people stopped embedding rebar in their bales. It covers both loadbearing and non-loadbearing buildings, though you can see the author’s preference for loadbearing throughout.

There’s so many topics in this book that I’m going to go ahead and just share the index rather than list them:

The sections on design I really loved, and the actual construction sections were also pretty great (though there was a little less attention paid to the challenges of framed strawbale than I’d have liked in spots). There’s almost no stone unturned on the topic of strawbale building here, and even better: they provide reading lists of more books at the end of every chapter! Wahoo!

This book is much more open to the idea of you completing a build yourself, or with friends and family than the Morrison book. It still acknowledges you’ll likely need a contractor to get a bank loan, but that I’ve already heard from everyone.

And now I’d like to make a sidebar on a different book - Essential Sustainable Home Design, also by Chris Magwood. This book I did not especially like. It covers briefly almost every form of natural building, but not in very much detail. The takeaways I got from the book were pretty much “Chris Magwood thinks you should not build a basement (because concrete is bad) or use foam insulation (okay I agree there).” There was much less on actually designing a home than I expected and, lo and behold, not only is there more on design in this book, many of the same paragraphs appear in both books.

Now, am I salty about this book because I know building a basement is bad from an embodied carbon standpoint but I intend to do it anyway? Maybe so, maybe so...but if we’re talking about things in construction bad for the environment that require further contemplation so is building single-family homes in general, and Mr. Magwood didn’t ask his readers to think twice about that. Anyway, it was fine but not a resource I intend to pick up again. If you weren’t broadly familiar with different sustainable building techniques it’d be worth a read for that.

Things I want to follow up on from this book:

Many! The entire design process proposed in here seems solid.

Checking through the reading lists to update my own

Use of silicate paints over clay plasters as an alternative to using lime plaster for water resistance while still keeping permeability

The possibility of renting the delivery trailer from the straw to keep them in storage until the bales are stacked

Blocking between joists under the toe-ups for a framed floor (this book does include basement hallelujah)

I-beam roof framing as an option?

They suggest using just plywood as the top plate for framed designs to minimize lumber, but then how where would you staple your mesh? Building some sort of box beam seems the only way to get sufficient nailing surface.

Plaster-wood interface. The book recommends not using roofing felt over wood framing for fear of trapping moisture next to the framing, but instead using a slip coat of plaster and straw stuffed behind the the plaster mesh to bridge the gap.

Using vapor barriers at ceiling, floor and post intersections. Not elaborated on in detail, but repeatedly mentioned as locations to seal air gaps.

Plastering tips (many)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bale Needle Ideas

During the Kentucky workshop there were two bespoke, just for strawbale construction tools that we used. I’m pretty sure the hosts had them commissioned from a local metal fabricator, but last night I went down a rabbit-hole of “could I do this myself, without learning how to weld”. These are my thoughts on bale needles:

Older style bale needles tend to be a steel rod with one end flattened and a hole drilled through the center (as seen below, photo from The Sustainable Home)

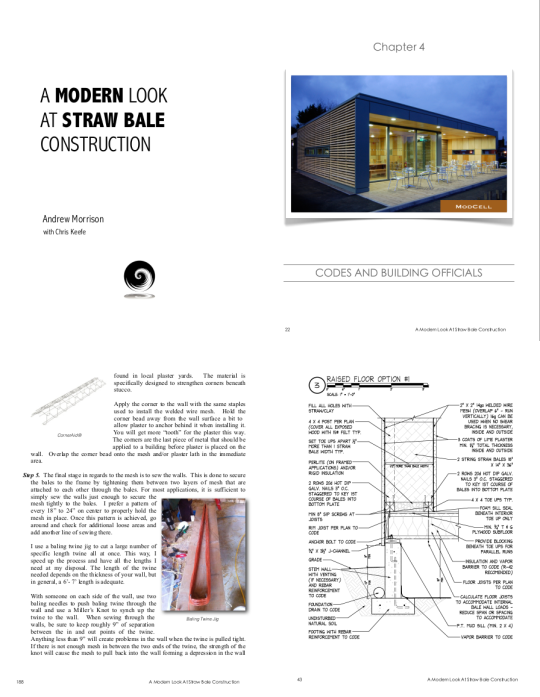

This design definitely works, but Andrew’s preferred design is different. Instead of a drilled hole, there are steeply angled notches at the end of the needle that are used to hold the thread as you push it through the bale. (see below, image from A Modern Look at Straw Bale Construction)

And here’s another great needle based on that design, from Daniel Siepman‘s website. He’s done a really deep notch (great!) and rounded off the point of the needle to make it less dangerous (smart!). The needle seems a little long but other than that, this is exactly what I’m looking for.

The big advantage of these needles is that when you push through to the other side and retract the needle, friction pulls the twine from your needle without you having to manually unthread it! This is a huge time saver. In theory I think you could use a needle like this to punch your twine to the other side of the wall for almost all your quilting needs, then circle around to the other side of the wall and do all the tying, thus allowing wall quilting to be a single person operation. (remains to be tested)

There were a few different bale needles on site, since some participants had brought their own. I found that the steeper and deeper the notch, the better the needles worked. Shallow notches had a tendency to let the twine slip before you made it out the other side of the bale. Some needles had welded metal handles and some were threaded on the end so they could be inserted into a wooden handle - both worked fine but the second option is obviously the no-welding option.

Now, Andrew’s design has three notches, but I think 90% of the time you could do fine with a single notch. The two back-angled notches are there so you could, theoretically, tie two halves of a bale at once for resizing. In practice, Andrew said that people quite frequently end up getting the lines twisted over each other so the mini bales can’t be separated and it’s less frustrating to tie the first mini bale, pull them apart, then tie the second bale.

The forward-angled notch is for situations where you’ve pushed the needle through, and then need to thread the needle and pull it back through. This could come up during wall-quilting, if you wanted all your ties on one side of the wall but had to sometimes stab from the other side to work around obstructions like shear bracing.

Now, for how to make the needle:

I think you’d want to start with a steel rod at least a quarter inch in diameter. I’m not 100% sure a quarter inch is enough, maybe 3/8 would be better? The needles on site were definitely not thicker than 3/8.

Notch first, with a single back-angled notch. This could definitely be done with a grinder, but given the level of precision you’d want, I think I’d start with a hacksaw. Draw on the lines for the cuts, steady the rod in a vise or clamp, then saw both cuts so they end in a point, You could then use a metal file to widen the back of the notch and smooth the edges

Cut off the tip of the rod at an angle, then again use a file to smooth the tip so it’s less lethal

Because I’d want to use a wood handle, the end of the rod will need to be threaded at the end. This is totally doable at home, I am told, but it sounds like a pain. Another option would be to buy an already partially-threaded rod - I found that steel float rods for water tanks seem to come double threaded and in various lengths (the Kerick SR18 looks just right). You’d just have to cut off the other threaded end when you made the needle point. Definitely more expensive than tapping the threads yourself, but not unreasonable if you only needed one or two needles.

Then you’d need to drill a hole through your wood handle. The handle should not more than 9 inches in length, and a comfortable diameter to grip. It could either be round or square, depending on your preference. The hole for the rod should be centered so you can easily apply pressure symmetrically as you push the needle.

For fastening the handle to the rod, you could either drill all the way through & then fasten with a pair of washers and nuts, or you could drill partway through and use a threaded wood insert. There’s not going to be a lot of torsion applied to the needle, so either way would probably work, depending on the amount of thread you’re working with and the thickness of your handle.

0 notes

Text

book notes: A Modern Look at Straw Bale Construction

by Andrew Morrison with Chris Keefe

A Modern Book on Straw Bale Construction was self-published by Andrew Morrison’s company, Straw Bale Innovations, in January 2012. It was written as an accompanying written guide to his hands-on workshops on strawbale construction. This does mean it was published prior to the 2013 finalization of the IRC Appendix S, but since Andrew’s design method is fairly code-conservative I didn’t notice anything that stood out as not matching the current building code.

He’s collaborated on this book with Chris Keefe of Organicforms Design to present a number of detailed, labeled engineering drawings of possible wall and foundation schematics. These really add to the quality of the book.

The majority of strawbale books have some fraction of convincing you to build with strawbales, the history of bale houses, practical considerations, design considerations, general building advice and hands-on building advice. This book is one of the first I’ve read that is majority hands-on building advice, which makes sense given that it’s structured around his workshop building method.

The method Andrew focuses on is based upon post-and beam framing with strawbale infill, where the bales are then covered by welded wire mesh and plastered with lime plaster. He presents both the reasoning for why he has chosen this method throughout the book as well as lots of advice on how to implement it.

There’s also a not-insubstantial section in the beginning of the book on how to get code or bank loan approval of your strawbale project. The biggest advice he has is not doing the work yourself and relying on expert subcontractors for the non-baling work, which is obviously inconvenient for me personally, who’s been starting with the assumption I would need to do as much as possible by hand to ever afford this project 😉. I’m sure he’s correct, I’m just not sure the advice is possible for me to implement.

The only two things I was disappointed on in the book was the lack of details on how to commission or create the two DIY tools needed for baling under this method (stretching forks and bale needles), and the decision not to hyphenate the typesetting. (I dabble in bookbinding in my spare time and have become a complete snob about type spacing)

1 note

·

View note

Text

book notes: Earthen Floors

by Sukita Reay Crimmel and James Thomson

This book was recommended to me during my strawbale workshop while we were discussing concrete slabs. Foundations are the one place it is very hard to avoid using concrete, which sucks. Concrete is a huge source of CO2 emissions (about 8% of worldwide emissions, from what I saw online); there are lower emission concrete mixes but that gets expensive and probably out of reach for a normal homebuilder. So then the question becomes: how little concrete can you get away with?

Personally, I have always wanted a basement under my home. It would give me a place for food storage, utilities and hobby space without needing another finished floor. I’d been imagining if you did a basement that you’d need to have a concrete slab for the floor, but folks at the workshop suggested you could do a compacted gravel slab topped with an earthen floor, so I checked out this book.

(fair warning the book does not *specifically* talk about basement floors, only slab-on-grade earthen floors and over-wood-framing floors. but based on what’s inside, I’ve extrapolated that you could totally pull this off in a basement).

I cannot remember where I’d first read about earthen floors, but whatever book that was had a very different approach - they were making a mostly dry mixture and then laboriously tamping it into place. Sukita’s book outlines a much friendlier sounding method - making a stiff earthen plaster mix and screeding and troweling it into place. The floor is then allowed to dry and then sealed with several coats of linseed oil. There are additional steps outlined for an even more polished floor: sanding, waxing and buffing the floor to get it super soft and smooth underfoot.

This book provides good explanations of:

Testing soil for use in earthen floors

Making test mixtures for earthen floors from your local materials

Prepping substrates (including tamped gravel slabs)

Installing earthen floors

Finishing earthen floors to varying levels of polished

It has definitely left me wanting to experiment with these methods, especially if my site ends up having a good clay subsoil. There aren’t a lot of other books on this topic so it’ll be difficult to do additional research. I’ll keep my eyes peeled for workshops.

Things I want to follow up on/think about:

Engineering requirements for a concrete slab floor in a basement?

Relative cost of earthen vs concrete floor

Weight calculations on earthen floors for over a wood subfloor...the method mentioned using burlap for tensile strength was intriguing and I’d like to hear if that installation remained solid longterm

Logistics for moving the earthen plaster into a basement (ramp with a plastic sled maybe, then transfer to a wheelbarrow at the bottom?)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pictures from Andrew Morrison’s northern Kentucky workshop, July 2022! Not using any pictures with people in it for privacy reasons, but you can see the house take shape over the week. So much time goes into the stages between finishing laying the bales and being ready to plaster (truing the walls, trimming the walls, electrical, roofing felt over the wood framing, 2x2 mesh and sewing, plaster lath over large pieces of wood), but you can barely see it in these distance photos.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Workshop Retrospective - July 2022

So this year I got to do something I’ve been wanting to do for a decade - attend a weeklong straw bale construction workshop. The workshop I attended was taught by Andrew Morrison (of Strawbale.com) and hosted by a very nice family in northern Kentucky.

The first thing I have to say is that it was an amazing experience. The workshop structure with a lot of groupwork, communal meals, late night music performances and camping on site really gave you a chance to get close to people and feel connected to a community.

(If any of my fellow Kentucky attendees are reading this, I was the person who went to the hospital for an infected spider bite. That was, obviously, not a highlight of the week but I only missed a little bit of the workshop over my 4 hour hospital waiting room adventure. My foot is once again the correct size & no longer cartoonishly swollen.)

We were lucky enough to attend a workshop attended by not only Andrew (who is an extremely gifted communicator and educator) but also Dee and Timbo, who will be taking over the workshop business after Andrew retires. They use a different style of building with straw, so there several opportunities to compare multiple methods.

The house we were working on was strawbale infill over an ICF walk-out basement. The method Andrew uses in all his workshops is as follows:

Preparing the toe-ups with their fill material and nails to secure the bottom course of bales

Placing the bales; notches are cut where necessary with a chainsaw. The last course of bales is oversized for the space and is used to compress the wall

Trueing the wall with a tamper

Using a weed whacker to smooth the walls

Stuffing any gaps left by the bale stacking

Cutting channels for & having electrical work installed in the outer walls

Attaching 2x2 steel wire mesh from toe-up to top beam (using pneumatic nail guns) in order to support the wall , then quilting the layers together through the bales

Shaping window/door reveals by stuffing with loose straw before attaching mesh in those locations

Plastering with a three layer lime plaster made of hydraulic lime

Because of the size of the house and the fact that you needed to use a ladder to get to most of the site, we didn’t get as far as most workshops do. We finished shaping about half of the windows and only got to work a little bit on plastering. However, I still learned a lot and it has given me renewed confidence in pursuing my own house project. Personally, I felt like I got more out of the workshop having already done a significant amount of reading, including reading Andrew’s book.

Here were some of my takeaways for any projects I build:

I can physically carry a bale, but I’d want to do more weight training before trying to carry many bales by myself or lift them into higher courses.

I am not tall enough to easily compress bales for retying in the way Andrew teaches. Either I need to build a setup to raise me up/lower the bales, or find a different method.

Sections between windows require no notching and are awesome

Notching bales with a chainsaw is doable, but I definitely want to try using a manual saw & see how much longer it’d take. especially on multi-notch bales, it was very difficult to get precise enough on a chainsaw.

Your notches will always need to be deeper than you think, so just add half an inch from the beginning.

The stage where you tension the wall by jamming a 14 inch bale into a 10 inch tall hole is not something I could do on my own. It really requires a person who’s six foot and has a lot of upper body strength to wield either a steel tamper or a large mallet above their head. I need to look into alternate methods of tensioning the wall (possibly using ratchet straps to pull the wall down beneath the last course so it would take less force to push in the last bale?)

I do not like the weed-whacker step. I could use a weed-whacker but I don’t want to - I’ll definitely look into quieter and more ergonomic options to smooth out the bale surface.

Without a wide enough top plate, it is very difficult to get the mesh stapled at a welded joint like you need for a secure hold.

Stuffing the rounded reveals with loose straw sucks and takes forever. Timbo mentioned that he does the window reveals with a cob mixture that’s covered by wire mesh and that sounds so much easier.

On types plaster

Andrew uses hydraulic lime, which can set regardless of the thickness of the plaster coat (if, say, there are large depressions that are filled in with the base coat). He does not use any straw in his lime plasters anymore, though it’s still in the video instructions he has on his website.

Timbo said he prefers hydrated lime, which is cheaper, easier to source, dries slower and excess can be saved by covering the plaster with water. A fiber for strength is required for hydrated lime. Timbo said that he avoids the issues of deep plaster layers by filling any divots/gaps with straw/clay before plastering.

I really loved plastering for the 30 minutes we did it, which tells me nothing about how I’d feel about plastering four hours into my third coat 😅

1 note

·

View note

Text

Have-read List - Reference Books

Books I've read, I'll try to add notes on these later. As I read more, I'm going to try and take notes in separate posts on especially useful books.

Straw Bale Specific

Books that were more photo gallery than reference books: Small Strawbale, The Staw Bale House

Building a Straw Bale House : The Red Feather Construction Handbook by Nathaniel Corum

Design of straw bale buildings : the state of the art by Bruce King

Serious Strawbale by Paul Lacinski

Straw Bale Building Details by CASBA

A Modern Look at Straw Bale Construction by Andrew Morrison

More Straw Bale Building: A Complete Guide to Designing and Building with Straw by Chris Magwood and Peter Mack

Other Natural Building Techniques

The hand-sculpted house by Ianto Evans et al.

Building with cob by Adam Weismann & Katy Bryce

Essential Light Straw Clay Construction by Lydia Doleman

House Framing

The complete visual guide to building a house by John Carroll and Chuck Lockhart

The very efficient carpenter by Larry Haun

Plasters/Finishes

Earthen Floors by Sukita Reay Crimmel and James Thomson

Building with Lime; A Practical Introduction by Stafford Holmes and Michael Wingate

Carpentry

Home Design/Theory

Building for a Lifetime by Margaret Wylde

Kitchen Think by Nancy R. Hiller

Make Your House do the Housework by Don Aslett

The solar house : passive solar heating and cooling by Daniel D. Chiras

Essential Sustainable Home Design by Chris Magwood

Musing of an Energy Nerd by Martin Holladay

Building Code

Residential Building Codes Illustrated by Steven Winkel

Foundations

Foundations & concrete work by Taunton Press

The Essential Guide to Foundations by JLC

Electrical

Plumbing

Project Management

Other

0 notes