Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

BFI Flare: Horseplay

A group of straight Argentinean men hang out in a beautiful home with barely any clothes on, while playing pranks on each other and sending compromising pictures to various WhatsApp groups.

The supposedly decades long bond between these characters is totally unsketched outside of their apparent need to test each others' sexual boundaries. The film therefore functions only as a homosexual fantasy of what straight male bonding looks like, while purporting to levy the critique that – shock! – there may be a homophobic streak latent within their homoerotic horseplay.

That this is the most simplistic possible thought on the subject does not stop the film taking two hours to make its point. And that the Gay Viewers' arousal at this implicitly homophobic milieu is the sole source of the films libidinal quality – and marketable appeal – goes lamentably unaddressed.

The mens' interactions are well observed in places, but the film is largely dull and dishonest, and aims to horn up its audience into looking past the redundancy of its content.

#lgbt#LGBT cinema#queer cinema#horesplay#homophobia#homosocial#film#film review#film writing#queer#gay cinema#bfi#BFI flare#film festival#argentinian cinema#argentina#Marco Berger#heterosexuality

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

BFI Flare: Chrissy Judy

Oooft. This one had my stomach in a knot. A sharply funny and melancholy story of how incremental personal shifts threaten old friendships, and how moving through the chaos allows for deeply felt bonds to gradually remake themselves.

In the best possible way, it reminded me of Looking, with its interest in the challenges of intimate platonic bonds as gay men round the corner of their thirties and try to figure out what a stable life might look like within a milieu that encourages clinging to youthful abandon and discourages foreclosing on options.

Wealthy elder gay couples with houses in the pines continue to be the boogeymen of such stories, as they well should.

Even if less well realised the film would stick out on the festive circuit, amongst the usual sea of queer coming of age retreads, as a lovely and amusing film about how the need to pick a path can feel so frightening when based in a community defined by its openness and freedom.

A staggeringly well crafted film given its $20K budget and 16 day shooting schedule, with – at times – beautiful black and white cinematography and unhurried, lived in performances.

#Chrissy judy#lgbt#queer cinema#LGBT cinema#BFI#BFI Flare#todd flaherty#looking#queer friendship#gay#gay cinema#gay friendship#Francis ha#review#film review#film festival

1 note

·

View note

Text

After Yang, and encounters with the Other

What is it that we know of the Other?

The Other seems complete to us, appears whole. The Other’s warmth appears to grant us the possibility of a safe place to rest, yet its latent threat renders total trust, total relaxation in its company, perpetually out of reach.

The slippage between the other as object – something that can be fully known – and the Other as a vessel of oppositional secrecy – a subject – lies at the heart of After Yang.

The plot; the robotic sibling of a tea seller’s daughter becomes nonfunctional, sending the adoptive father in search of someone to fix him. We soon find out the son was harbouring prototype spyware – outlawed due to concerns for human privacy – by which his hardware recorded a moment each day that had triggered something within him.

At one point, an academic museum worker with designs on these recordings remarks that what the robot records reveals precisely what was memorable to that robot; it offers a glimpse into its psychological needs and desires.

Later, reviewing some of these memories through an ocular device, the father discovers a life far beyond what he knew this son to have been capable of experiencing. These memories reconstruct furtive glances, moments of self recognition, feelings of lust and longing. Through prying into these private memories, the father is able to recognise his son as a true individual for the first time; full of warmth and love, but also secrecy. But to have stumbled into knowing this Other, the father has trespassed its privacy, and its right to interiority, concealment, and private experience.

The central couple ponder the possibility that this robot sibling, who they treated as a second class domestic worker and tutor for their child, may have possessed an authentic humanity after all.

A scene between the mother and the robot son. “Is dishonesty a choice you can make?” she asks. “I’m not sure,” he replies, in the soothing tones of home AI, designed to soothe any operational friction or resistance. The status of the robot’s humanity – its potential to harbour an oppositional force – dances around the edges of the conversation.

Throughout the film the family regularly appear to each other as holograms, or as disembodied voices on a phone call. Communication is an act of mediation. Yet to appear to another person at all is always to be mediated through that other’s own consciousness.

A flashback to a scene between the father and the son. “Why are you so interested in tea,” the son asks his tea-seller father . “I saw a documentary about it,” the father replies, “where a German man claimed he can taste a damp forest morning within it.” The father and robotic son pour themselves a mug. The son express his wish for a greater experience of the tea than his condition allows. The father reluctantly admits he too is not sure he can taste the forest. The thesis of the film lies here; one thing is always the other, existing in a mercurial state between what we know it to be, what it might once have been in a prior time, and what it might yet become.

Is an ending really a beginning, the mother ponders, or rather, must an ending offer a new beginning for us to be able to access it? Perhaps, suggests the robot, the possibility of a true end provides both comfort and meaning to the something we currently have.

But have any of these characters truly experienced an ending, with its attendant promise of rupture and rebirth, or are they still stuck in a present moment that is continuous with the past? The protagonists of the film are moving endlessly forward, yet their futures are informed almost entirely by their backward glances. Traces of the robot’s zip-filed memories are revealed to have guided he actions of his final days. The father looks back over these memories, trying to feel closer to his son, all the while his son’s life is slipping further from grasp. Both long to repeat - or perhaps to right - past failures, and this guides them through their present.

The film is beautifully designed, soft and warm; all plants and exposed concrete and soft birchwood. But the tactility and snug surroundings of the film’s domestic idyll conceal a cynicism in their performance of bourgeoisie authenticity. The reassurance they hold - to be authentic, to be natural, to be apparently real, reveals the precarity of the homeowners’ sense of self, and longing to overcome their alienation. These beautiful objects provide a guarantee of their trustworthiness. The display their materials and thus can be trusted to be objects. The Otherness of their robot son, who they owned in life, and whose memories they own in death, upset this naturalised order between the object and the subject.

After Yang ends with a jarring final scene, which may hold the key to everything, or perhaps nothing at all; except perhaps a reminder that life’s great mysteries, the meaning of life and the people that fill it, always remains a little out of reach.

#After Yang#The Other#Film#film critique#film criticism#film essay#scifi#science fiction#existentialism#sartre#colin farrell#kogonda#jodie turner smith#essay#writing#writers on tumblr#saying goodbye to yang#Alexander weinstein

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return

A feeling of dread and an unsettlingly ambiguous mood hangs over this story of two boys spending a week on a road trip with their domineering and suddenly resurfaced father.

The eldest brother, on the cusp of adolescence, wants to accede to the demands of his father, and seems willing to acquire something of the self-mastery and emotional suppression required to become a man in the world he inhabits. But the ever-present film camera hanging around his neck reveals something of his sensitivity, and desire to find both beauty and certainty in the world around him, even while the futility of looking at a situation that none of its participants can quite understand is laid bare by the film’s constantly shifting framing. The younger brother, meanwhile, is preoccupied with anger towards the returning father and his unarticulated self doubt in the face of being asked to rise to the level of the masculine ideal his father enforces, while his simmering and ineffectual rage powers the film towards its heart stopping denouement.

The father remains mysterious to the boys, both in his life, his work, and in the intentions behind his brusk and cruel methods of parenting. But we feel his uncertainty as he navigates new terrain of parenthood, while demanding to claim his position of patriarch, both for himself and in order to forge these young men in his image, however misguided that mission may be. Over the course of the week in which they take a step towards adulthood, the boys gain something undefinable and lose something ineffable.

The film deftly captures the unreality of living through a rupture in one’s existence, and the strange uncertainty of experiencing something formative that one can’t quite comprehend in the moment.

Would make an interesting double bill with last year’s The Power of the Dog.

#Andrey Zvyagintsev#Zvyagintsev#The Return#Power of the dog#the power of the dog#adolescence#coming of age#review#cinema#film#cannes#cannes film festival

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Freedom, Genet and Foucault

One of the most ambitious and incisive queer films of the year, Great Freedom - which won the Jury prize in Uncertain Regard sidebar at the Cannes Film Festival and was Austria’s official selection for Best Foreign Language Film - offers an incisive evocation of the lingering impacts of institutionalisation on the psyche. Rarely is a film so restrained in its anger over injustices of the recent past, which many societies who call themselves progressive would wish to forget. It stakes its claim amongst the works of great queer artists and theorists who have explored the romantic potential of the prison, while offering a moving critique of the criminalisation of sexuality, and a rigorous exploration of what it really means to exercise our liberty. And in a year which saw lockdowns continuing around the world, a film illustrating the lasting mental scars of incarceration may have acquired an unintended significance.

West Germany, 1946. Paragraph 175 - a century-old penal code which criminalises homosexual activity - is still being well and truly enforced by the watchful eyes of the state. We first meet our protagonist, Hans, a libidinal and tortured ne’er-do-well through the voyeuristic eye of a camera hidden in a public bathroom which is being used for a police sting operation aimed at rounding up homosexuals. Adrift within civil society, the gay men of West Germany - like many others of their time - are finding love on the margins in public bathrooms; squalid homosocial spaces whose alternative use as a cruising spot perhaps only reinforced the contemporaneous perception of homosexual depravity. Men make eye contact with one another at the urinals, before moving into the stalls, whose offer of privacy is eventually discarded in favour of intoxicatingly risky out-in-the open encounters. A strange mechanical quality hangs over the scene, as fornicating men are viewed dispassionately by the quietly whirring camera. We, like the West German state, are surveilling their bodies with no regard for their interiority. Hans enjoys a sequence of amorous encounters in the bathroom stalls, but being watched seems to be part of the fun, as we realise when he briefly flicks his eyes into the lens of the camera. The next thing we know, he is pulled before the German court to answer for his crimes, and he’s carted off to prison, which we quickly surmise is a familiar environ for him.

The film speaks to the present moment which may appear to be something like the end of history for the gay populations of Western Europe, as preventative HIV treatments and sex positivity permit casual, polyamorous sex lives, and paths to normative lifestyles of marriage, kids and career have been well and truly beaten. But Great Freedom dares to ask how it is that we can forget the injustices heaped upon our forebears who suffered through the criminalisation of homosexuality. How can we forget the physical and psychological scars wrought on their bodies and minds by decades of unimaginable institutional oppression?

The gay male erotic image has long been fashioned on society’s margins, and the film captures something of the libidinal charge long examined by queer artists in the relationship between the oppressed and their oppressor. The film contributes to the long cannon of queer works which locate and luxuriate in the inherent sexuality of the abjection and longing found in that most homosocial environment - the prison. Queer filmmakers, writers and artists have long probed the tense eroticism of indulging desires in the places where they are both aggressively fed and ardently policed. Jean Genet’s horny screeds such as Our Lady of Flowers, written (and rewritten) from behind bars find an erotic charge in the connections between criminality, repression and sexual longing. The work of queer artists such as Tom of Finland take a fascistic visual enjoyment in the BDSM aesthetics and hardbodied, uniformed, ubermensch figures that he makes his subjects. Films like East Palace, West Palace overtly explore the sexual dynamics of authority. But perhaps the most influential queer chronicler of the prison is the legendary French philosopher Michel Foucault, whose pioneering works - Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality - coalesce around the ideas of restriction of both the flesh and the mind. For a certain group of queer artists, therefore, the prison takes on an almost catholic quality - a place of love, shame and denial. This is certainly the case in Great Freedom. And so the film offers its own contribution to the plethora of queer works which have seen sexuality and violence as intertwined political, psychological and aesthetic experiences.

The film’s non-linear structure charts Hans’s time through several stints of incarceration. The disorientation created by the film’s fragmented timeline helps capture an endless temporal space of incarceration - the drudgery of routine and the boredom of the familiar are compounded by the film’s focus only on Hans in his time behind bars. One begins to scarcely be able to imagine a time before, after, or outside the prison. Over time, Hans develops intimate relationships with a number of men by encouraging them to defy daily cell checks in order to be snatch a few extra hours together, huddled under blankets in the freezing night air of the detention centre. These tender moments in the prison’s cells and yards conjure thoughts of Genet’s staggering short film, Un chant d’amour, in conception if not execution. Where Un chant d’amour is an aesthetic exploration of the agony and ecstasy of imprisonment, Great Freedom is a much more pragmatic, procedural film. It is enamoured of the ability to find beauty within the prison’s oppressive concrete and wire structures, but not so absorbed with the erotic charge of separation that animates Genet’s sumptuous film, where smoke exhaled through vents provides a sensual caress to the muscular cellmates caught in suspended arousal by their agonising separation. As Hans and his lovers’ breath mists in the freezing air, one feels the pain, beauty and sacrifice of their forbidden love. Both films teem with sexuality and longing, but the Great Freedom’s narrative and psychological intent takes stock of the suffering, while Genet subsumes any such thoughts into the hardbodied autoeroticism of the lonesome cell inhabitant.

This psychological burden of imprisonment is captured perfectly by Franz Rogokowski’s lithe physicality as Hans. He is an instinctual and melancholic anchor, perfect for a story about tenderness found amongst the ruins. His angular jaw, his hollow cheeks, his haunted eyes, and his cleft lip suggest a man who has been routinely beaten down by life. He peers out cautiously from under his brow while his hunched shoulders reveal the psychological scars of a life spent at the physical mercy of authority. But his toned body and defiant, self contained emotional life reveal his resilience, his libidinal sexuality and at times, his free-spirited jouissance. He carries a rage and a confusion that runs up against the cold, unfeeling walls that constrain him, yet he carries a romantic longing and vulnerability which leads him to look for beauty in the darkest of places.

Throughout, the camera tracks economically through the space of the prison, juxtaposing characters against walls and wire fences which fill the entire frame behind and around them. The prisoners are all kitted out in ironically sky blue shirts and ocean blue trousers, creating an escapist sense of solitude and calm within the bloody red bricks and greyish blue plaster of the prison. And in the midst of this bleak setting, love still finds a way.

A lost love is remembered in a sunny scene shot on grainy film stock, in a sequence rife with nostalgic longing. One of few sequences set outside the prison, and like the opening film’s opening moments in the public bathroom - it has a sense of unreality thanks to the mediating device of a film camera, as the memories come back to Hans as if they were a film he shot himself. But where the earlier scene in the bathroom has a fixed composition and dispassionate gaze which captures the normalcy of a good public fuck, the second sequence tells something of Han’s romantic interiority - the easy lustfulness of those verdant summer memories now lost to time.

The central relationship of the film is that between Hans and his cellmate Viktor. Early revulsion and disgust towards Hans as a homosexual softens once Viktor notices the serial number tattooed on Hans’s arm, a reminder of his time imprisoned in a contraption camp during the Third Reich. Through the tattoo we understand that the new German government’s continuity with the earlier Nazis in their incarceration of homosexuals. For many, the dawn of a new era in Germany offered no respite from persecution and imprisonment. And so Viktor offers to tattoo over the mark, a tender and sensual act of care between men which caries with it the needle's stinging pain. And thus two men begin to forge something like love in the concrete walls of their prison. And while Hans searches for the carefree days of his lost love in the younger men he pursues, with Viktor he finds an older protector to guide him and offer a steady reassurance.

The film’s closing moments conceal a gut punch which offers the film’s most straightforward statement of its critical intent. Paragraph 175 is to repealed, and Hans is to be freed. Newly liberated, Hans enters the dimly lit, cavernous halls of a sex club littered with copulating bodies; a place for hedonism and self-reinvention through anonymous sexual encounters. But Hans - contemplating this newfound freedom to indulge his passions openly - is overwhelmed, and out of place. He runs to the nearest shop front and throws a rock through the window, before lighting up a cigarette to the sounds of the store’s alarm. He calmly waits for the police to cart him back to the clink. It is a wryly humorous reversal of course which turns the film’s apparently happy resolution on its head, and casts all the misery that came before in a newly tragicomic light. The film’s denouement is an ironic statement of ability to use our freedom to shape our lives how we see fit - even if that is by willingly resubjecting one’s self to incarceration.

In his 1975 book, Discipline and Punish, Foucault offered an infamous analysis of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon as the prison par excellence, in that it encourages the prisoners to regulate their own behaviour, by obscuring the guards from view, so prisoners are never certain whether they’re being surveilled. They therefore begin to act as if they are always being watched. In this way, the prison’s regulation of the prisoners leads to the prisoner regulating itself. This is the affliction Hans suffers from. As Foucault writes in the book:

“[The prisoner] assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles [of prisoner and guard]; he becomes the principle of his own subjection.”

The film’s strength is in how it captures this effect - the reflexive relationship between the subdued inmates and the psychosocial barbarousness of life inside an inescapable institution. This is not a prison story of pride and resilience, but one of the necessary and total capitulation to your tormentors.

Historiographers of Foucault’s work frequently point to the moment where he moves from writing about systems of control and bodily regulation - as in Discipline and Punish - towards the ideas the new forms of reinvention and freedom offered by the nascent and permissive neoliberal societies in the late 20th Century. This is the society Hans finds himself entering. These societies offered a freedom from the overreaching and regulatory states of the mid 20th century - and moved towards more flexible and internalised systems of control. In academic circles, this time - tied inextricably to the onward march of gay liberation in the period - was seen as offering a new horizon of self definition, actualisation, and alternative lifestyles within functioning social systems. But what Great Freedom dares to ask, is how are those oppressed by the previous order, who have spent their life accommodating and learning to live under the long arm of the state that despises them, supposed to actualise and connect? When their lives have been spent confined by physical and psychological walls of state institutions, how should they know how to be without them? It offers scathing inditement of the moral crimes that governments have inflicted on persecuted minorities for decades. And it captures the overwhelming terror that the falling away of familiar structures can incite, however painful they might have been to endure.

In this way, the film’s illumination of the psychological impacts of physical oppression is a firm rebuke to anyone who would like to consider gay liberation passé. Such concerns are sadly still relevant today, as we see in the current struggles across the Anglo-sphere to end conversion therapy, a practice which at its core is an attempt to control the mind by regulating and harming the body. Already illegal in many US states, it was recently outlawed in Canada, and legislation is currently being tabled in New Zealand and the UK. But in all countries, conservative forces have opposed the ban, and there are no guarantees these laws will pass.

And so the struggle for freedom - the human desire to be able to live openly and comfortably in the world and within one’s own self - is delayed for another day. And it is this struggle which Great Freedom captures beautifully, with clarity, humour and eroticism.

#Great Freedom#LGBT#LGBT Cinema#Queer Cinema#Austrian film#austrian cinema#essay#review#film review#writers on tumblr#austria#gay#gay cinema#foucault#michel foucault#jean genet#genet#un chant d'amour#tom of finland#cannes#cannes film festival#uncertain regard#Sebastian meise#franz rogowski

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Matthias & Maxine, Xavier Dolan (2019)

#Instagram#Matthias & maxime#Matthias et maxime#Xavier dolan#dolan#cinema#film#arthouse#LGBT#LGBT cinema#queer cinema

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

American Gigolo, Paul Schrader (1980)

0 notes

Text

instagram

Grass, Hong Sang-soo (2018)

0 notes

Text

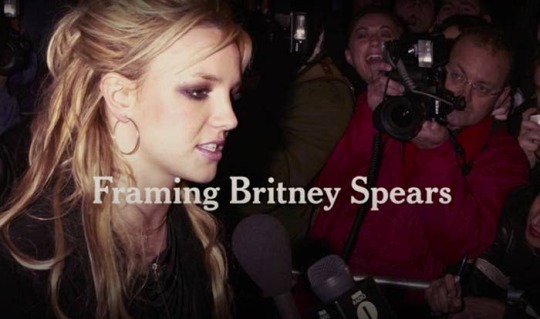

Framing Britney Spears: An Underwhelming Portrait

Framing Britney Spears, the new documentary produced for Hulu by the New York times, attempts to revise the popular image of Britney Spears, painting the star as a sacrificial lamb in the face of patriarchal media, legal and family systems. But it wastes it’s broadsheet-paper pedigree by resigning itself to being a slickly-produced, but largely unilluminating celebrity biography of the usual stock.

The contributors who most steer the shape of the film’s story are largely the paper’s own senior editors and reporters. While the archive is clearly well researched and features some obscure picks, the result is a documentary that feels like not so much a piece of investigative reporting as an exercise in retelling while gently revising a well known narrative.

The big “get” for the filmmakers is the participation of Felicia Culotta, Britney’s long-time chaperone, who holds a special place in the heart of Britney fans as an unusually friendly public face for the layers of protection that surround their favourite star. But the documentary’s reliance on the insights she has on Britney the person renders the film closer to a standard hagiographic biography, and loses focus on the ostensible interest of both the title and the first half of the doc; how and why do star images become codified, commodified and abstracted? In this vein, the doc gestures at the now popular idea from star-studies pioneer Richard Dyer, that effective star images are those that manage to satisfy an inherent contradiction. The doc shows us how the young Britney came to represent the virgin and the whore, as a slew of international journalists and talk show hosts line up to ask cringe-inducing questions about her breasts and her virginity. But the film drops this illuminating analytical focus as Britney slides head first into her Hollywood Babylon years.

The film’s attempts to frame her in the first half end up at odds with themselves. The filmmakers frame the young Britney in two ways; as a capable young woman who made things happen, and as a victim of a media machine which could only conceive of her through sexist paradigms and which wanted to mistreat her accordingly. Despite arguing that Britney was never a puppet; that perhaps she used the cards she held to court this type of attention, both in her younger days and when she plunged head first into her time as a paparazzi magnet, the film doesn’t seem to want to touch the reciprocity of Brit ey and fame. The film’s first half is too informed by what the legal proceedings that come in the films second half; it is consistently most interested in young Britney as victim, as a lamb for the slaughter of a sexist media machine, while shying away from giving her credit for how she used that control; Britney courted the attention of the press as it got her where she wanted to be. It was only after a period of unimaginable success that the bargains she struck revealed themselves to be Faustian. Vanessa Grgoriadis’s 2008 Rolling Stone article, “The Tragedy of Britney Spears” offers an alternative vision of a Hollywood hillbilly engineering and thriving on the chaos around her, as much as being victim to it. This tension is only allowed play out in the New York Times’s doc through the interviews with paparazzi who hounded her. Here the film offers the films most heated line of questioning, which result in revealing and honest moments of tension.

“I wanted to be a filmmaker,” bemoans Daniel Ramos, the videographer who provides the film’s window into the world of paparazzi. There’s desperation and ambition on all sides of the lens. Watching back this footage - pulled from news services like Hollywood.tv - one is struck by how the celebrity journalism of the time acquired an aesthetic that perfectly captured the age-old anxieties about Hollywood as a cesspit of moral depravity, meaninglessness and nihilism. At the advent of online video streaming and camera phones, footage of Britney running out of gas station bathrooms is full of digital artefacts and strobing, blown-out for extended periods by machine gun like camera flashes whose creators haunt the edge of the frame. And there’s Britney at the centre acquiring a further unreachable quality; distorted beyond recognition by compression and aliasing; her presence apparent, but the actual details of her actions and movement lost to a 360p youtube streaming form 2008. One feels more intimate with the star than ever yet their humanity is more remote than ever. Chaos and confusion rains both in the content and the form of digital tabloid videos. But the endless procession of different instances of Britney Spears frightened and alone shielding herself from the ceaseless flashes of the Paparazzi’s cameras drives home the humanity of someone at the midst of a decades-long media storm.

The film tries to tell two stories in its scant 75 minute runtime; that of a woman imprisoned by the media, and that of a woman imprisoned by a labyrinthine legal framework by which her father has disposed her of her rights, and made her pay him for this services so that she now faces the unenviable position of endlessly funding opposing teams of lawyers to contest her freedom. These two strands never quite come together, other than in how this once omnipresent star now communicates only via the ouija board that is her Instagram, operated by her conservatorship team interceding the messages she passes from her stultified ivory tower to the land of the living.

It’s this latter thread, about a complex system of direct exploitation aided by the legal system, that one would expect the New York Times to use its investigative clout to explore. This is a celebrity story that exposes how a legal system offers the potential for exploitation as industry; indeed, Courtney Love has alleged one of the architects of Britney’s conservatorship tried to force her into one too. And the film certainly addresses some of the key aspects of the case, without doing any investigating. The film is an interesting product of legacy media unmooring itself from old-media celebrity journalism models of kowtowing to publicists for access. But beyond a few hypothetical comments from lawyers and some conjecture, there’s nothing new revealed or uncovered in this documentary. As with all of Britney’s commodified and reported-on life, it remains a piece of entertainment.

The doc offers plenty of implicit critiques of the media, and seems to have inspired a widespread feeling of shock amongst audiences about how mistreated Britney Spears was at their hands. One must assume those realising how cruelly she was treated were quite happy to unquestionably consume her downfall at the time.

For non-Britney fans, the film provides what I’m sure feels like a new and fresh reappraisal of the career fo a superstar that faded from infamy. But for anyone invested in the stars career or misfortunes, the story told in this film is the only story of Britney Spears for the last fifteen years; someone who has been victimised but refuses to be a victim.

#Britney Spears#Framing Britney Spears#New York Times#Documentary#Review#Film#Cinema#Film Review#90s#y2k#britney#00s#2000s#hollywood#celeb#celebs#celebrity#fame#movie#doc#doco

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Once in a while when I wake up, I find myself crying.”

#Your Name#Anime#Love#Romance#Japan#Landscape#Cityscape#nature#fate#teen#Makoto Shinkai#art#animation#film#world cinema#cinema

11 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Tommy Cash raps a widely deranged guest verse, segues into singing the year's tightest pop chorus in an Estonian accent, Charli samples herself as a ringtone, the time signature changes up, eurotrash synths rise up under rolling hi hats and Cash's chopped vocal starts screaming what sounds like "ITCH BITCH DELICIOUS" down the phone at a robotised Charli.

And then a choral coda reveals itself and you realise it was sitting beneath the year's most insane production the entire time.

Amazing. 100/10 song.

#Charli xcx#Tommy Cash#A. G. Cook#A G Cook#PC Music#Pop#Pop Music#Pop 2#Mixtape#Spotify#Amazing#Music#Album#Track#Review

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call Me By Your Name - “Masochist”

Call Me By Your Name is a book that enraptured, provoked and decimated me. But it is a not a book that I can truly love. It's ruthless excavations of the machinations of desire are too exact, its costing of fleeting perfection's price is too depressingly high. It's painfully uncooperative in the way it offers no answers to the question it seems to raise – how can one live a life that contains perfection without all else being cast in its dreadful shadow? A romance novel with high-brow aspirations and little regard for gratification, it asks – “are all lovers masochists?”

The book is an aesthetes dream, unfolding over a languorous summer in a never specified location along the Italian Riviera. The ephebophilic male relationships of the Greek and Roman empires, which must have taken place under the very same Mediterranean sun, undergird the romance between a preternaturally wise seventeen year old and the american philosophy student boarding at his family’s home. Elio, the younger of the pair, is a deep thinker, well read, a talented musician – the perfect receptacle for readers' regrets over misspent youth. Why did one not learn the piano when one felt the inclination? Why did one never read the classics when one had the time? Oliver, the older, is finalising a book on the classical philosopher Heraclitus, whose key thesis is that everything must always exist in two states – the downward-leading path is also always the upward-leading path. Oliver, of all people, would know that all is both coming and going, converging on a single vanishing point, whilst being already past it. The reader too shall learn this over the course of the novel.

“Call me by your name, and I'll call you by mine” - the phrase, spoken by Oliver in a moment of passion, from which the book derives its title. The idea? That two lovers can become almost one, that fixed signifiers can be reassigned through a moment of sexually charged semiotic chaos. Each makes love to himself, whilst experience something of what it is for their partner to make love to them. Is the jousiance of this merged perspective of self-as-other derived from pure narcissism or extreme selflessness? Have the four walls of the percievable world been exposed only as curtains hiding a boundless expanse? None of this really matters; life after this peek into a new world is the same as life before – leading too and from this transcendental moment.

Call Me By Your Name is a book enraptured with the deep scars time cruely leaves as it carries the present to the recesses of your memory – like a ghost clinging to significant objects, evoked through sense memories and experienced only in the aching feeling of absence, and the sense of having been short changed. It's a heartbreaker of a book, offering piercing insight and astute observation, but no indication of how to escape the familiar trap the novel's protagonist finds himself in. I suspect my life may now have found a new before and after of its own – preceding and receding from Call Me By Your Name. The book is a warning of the price of perfection, but like the lighthouse that can barely be glimpsed through the storm, it’s a warning only useful once the final course has been set.

Call Me By Your Name, written by Andre Aciman, is available now in paperback, and coming to cinema's this Friday in a lauded adaption from Luca Guadagnino which stars Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer.

#Call Me By Your Name#Book Review#Andre Aciman#Luca Guadagnino#Armies Hammer#Timothee Chalamet#Romance#Book#Novel#Writing#Essay#Criticism#Heartbreak#Masochism#Youth#Italy#Film#Cinema#LGBT#LGBTQ#Gay#Gay Stories#Gay Writers#Queer#Queer Art#Love#Thoughts#Feedback Welcome#Feedback Please

143 notes

·

View notes

Audio

🌸 l8 summer 7teen 🌸

pull up a chair n wind down ur summer with a cool drink, a cig or 2, n some melancholy bangers

#summer#summer2017#playlist#music#bettywho#bjork#muramasa#tyler the creator#betty who#mura masa#banks#peaking horizons#the drums#arca#sza#ctrl#sea ctrl#scum fuck flower boy#flower boy#lana del rey#sigrid#terror jr#lorde#cardi b#dram#niia#lil yachty#cashmere cat#blue hawaii#charli xcx

1 note

·

View note

Text

Skinny Jeans Zine

I’ve been trying to figure out how to write about my experience with disordered eating and body image for a while. But as the contents of my laptop’s “Drafts” folder can attest, I haven’t yet found the right angle to approach it from. If you’re interested in this kind of thing though definitely check out Melissa Broder’s So Sad Today essay, which is incredible.

Anyway, my friend organised a zine fair in Leeds this weekend which I just got back from. (Incidentally, if you’re based in the north of England definitely look into Scream Zines. They’re a young organisation but they host great events and are lovely and welcoming.) Anyway, one of the workshops was a how-to for zine making. As I started designing, with no idea what I was aiming at or trying to express, some of my anxieties found expression on the page. Creating through collage, and recontextualising the media I passively consume from magazines was, in retrospect, obviously the most efficient way to work through my complexes on this stuff, and actually opened me up to new connections I unconsciously held regarding the relationship between the body, sex and aspiration. I also felt like a good anti-capitalist Situationalist, practising the fine art of détournement. Not that any of this will come through in the zine, which is reliably adolescent. My brand is nothing if not consistent.

Anyway, you can check a scrappy PDF of the zine out here. Please excuse the gross warm colour balance and quality. I think I’m going to try and expand it with writing and probably more collage. We’ll see.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Link

I recently had the chance to chat to the insightful and lovely MØ about punk, pop and politics. Check it out! 💖✨💕💫

#MØ#MO#Momomoyouth#moomins#interview#punk#pop#politics#singer#talk#chat#journalism#writing#writer#magazine#print#tank magazine#tank#tank mag#publishing#music#pop music

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

DIY Grimes is the best Grimes.

0 notes