21. working at the intersection of art, science, and society. montreal, canada

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

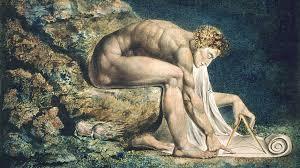

Undergrad Thesis: Introduction

They began to weave curtains of darkness, They erected large pillars round the Void, With golden hooks fastend in the pillars With infinite labour the Eternals A woof wove. and called it Science.

— William Blake, The First Book of Urizen

***

In early February of 1805 then burgeoning English chemist Humphrey Davy gave the first of a series of ten public lectures at the Royal Institution in London. The purpose for this lecture series was manifold. Having just returned from a geological expedition to Northern England and Scotland the previous year, the lectures were foremost intended to present Davy with a forum to exhibit his new collection of rocks and minerals. Yet, from the very start of his first lecture, members of the Royal Institution would have realized that the young scientist had taken considerable liberties in the scope of his project. Those in attendance who had expected a foray into the rock formations of Scotland would have been sorrily disappointed. Rather, on that fateful February afternoon at the dawn of the nineteenth century, Davy began by proclaiming that “the love of knowledge and of intellectual power is a faculty belonging to the human mind in every state of society; and it is one by which it is most justly characterized—one the most worthy of being cultivated and extended” (3). Indeed, nowhere in his introductory lecture does Davy make even the slightest allusion to geology, the proposed topic of his orations. Davy’s professions over the next ten weeks would set the pace of scientific endeavors for the next century and beyond. In his lectures, Davy details a glaring rebuke of the natural philosophers and scientists of centuries past. Commenting upon topics from scientific philosophy to the history of science and its role in the foundation of modern thought, Davy traced the course of scientific innovation from the ancients to Galileo and Isaac Newton. For the next ten weeks Davy continued in the same vein, presenting an inexplicable mixture of geology and scientific epistemology to packed lectures hall.

Underpinning Davy’s argument on scientific epistemology is what the chemist considers the most suitable method for deriving knowledge from nature. Facts and facts alone are the reliable basis for our understanding, Davy argued, adding to this a notable contempt for theoretical speculation. In his practice as well as in common life, the scientist, Davy contends, “ought only to be guided by certainties” or, at the least, by “distinct probabilities” (45). The most flagrant fault of scientists’ past and present being their choice “attribute to agents powers which they have never been observed to exert, or refer effects to causes, the operation of which they are ignorant” (70). To Davy, then, progress in science clearly is made in proportion to an increasing reliance on detailed observation and experimentation. He concludes that any person who calls themselves a scientist while turning a blind eye to observational detail will inveritably reach suppositions that “do not merit the name of science” (70). Davy further makes the case for meticulous experimentation by offering a comparison of two scientists that represent what are, in his opinion, the two vastly different epistemologies that undergird modern practice. To be held in the highest esteem is Francis Bacon, English philosopher and statesman credited by Davy as paramount to the European scientific revolution. Bacon, on who’s work the scientific method was founded cast inductive reasoning and empiricism as essential to the practice of “good” science. Contrary to the previous generation of natural philosophers who relied on some observations but primarily on deductive reasoning, Bacon’s staunch adherence to fact set him apart from his contemporaries. While “many scientific persons before Bacon had pursued the method of experiment,” he was the very “first philosopher who laid down plans for extending knowledge of universal application in all its precision” (39); a man who

wholly altered the face of every department of natural knowledge… Though much labour had been bestowed upon these extensive fields of investigation, they had hitherto…been little productive. Speculation had been misplaced, observation confined, and experiment principally directed rather towards impossible than to practical things. (39)

To contrast the towering figure of Bacon, Davy chooses Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, German polymath, and an important figure in the occult movement of the sixteenth century. Whereas Bacon is “uniformly directed by reason,” (39) Agrippa, the failed scientist that he is, rather “begins by supposing” (36). With obvious contempt, Davy accuses Agrippa of suggesting the “grossest absurdities,” finding it “difficult to conjecture from them whether he is self-deluded or… endeavouring to deceive others” (37).

More so than simply condemning the work of the latter early scientist, Davy extends his professional critique into a personal assault against Agrippa’s character. Davy actively portrays Agrippa as lesser than Bacon, emphasizing a new notion that would later become commonplace in nineteenth century academies: That the scientist is not sperate from his science, but that the perceived failures or successes of the investigator reflect the character of the man beyond the laboratory walls. In Davy’s characterization Bacon “was prepared by nature,” a “genius” whose “knowledge was extensive” and yet “gifted with a vivid imagination” that could nonetheless be “modified by a most correct taste” (39). Bacon’s scientific aptitude is conflated with the “influence of rank,” (40) and mention of his high political station. Whereas Bacon’s name would be remembered “into future ages with great and unchanging glory,” (39) Davy closes his section on Agrippa by depicting him as a wholly reprehensible character, a common “magician…vulgar” who will be remembered for his failed philosophies, “miserably poor,” (37) and as a lifelong prisoner to his own misconceptions, if remembered at all.

The image that Davy paints of Agrippa, a man forgotten to time and ridiculed by his successors, is as much a lesson in history as it is a warning to future scientists. Through the crowded lecture halls of the Royal Institution echoed Davy’s new idiom for science—facts are facts and facts alone are to be considered truth. To those that dare to “despise the logic and forms” (39) of Bacon’s perfect scientific method, Davy warns, should beware the wrath of a growing scientific community and prepared to deliver a “humiliating confession of ignorance” (39). The reasoned past of science, although presenting “romantic pictures” of nature should not, however, “in the slightest degree affect the opinion of the sound and judicious” (3) modern scientist. Speaking on the strong logical foundation of his argument Davy, somewhat paradoxically, concludes that such “truth scarcely requires any demonstration,” (3) although demonstration is the only way the scientist could arrive at facts and, through them, truth. The age of reason was over. The age of science had begun.

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, in their seminal study Objectivity (2007), chart the proliferation of this new scientific epistemology espoused by Davy and others through what they coin as “reasoned” and “mechanical” images. Belonging to the epoch of what Daston and Galison call “truth-to-nature” is the “reasoned image,” the “imposition of reason upon sensation and imagination” (98). Through the “exercise of will and reason in tandem,” (98) scientists prior to the late eighteenth century could forge an active scientific self, inclusive to non-empirical hypothesis, without fear of retribution from their colleagues. As evident from Davy’s lectures, beginning in the early-to-middle nineteenth century there emerged a new epistemic virtue, to draw again on the terminology used by Daston and Galison, called “mechanical objectivity.” The “mechanical image,” in contrast to its predecessor the reasoned image, sought to dissolve any trace of the scientific hand responsible for its conception. Mechanical images are thus “wary of human mediation between nature and representation,” (120) forcing scientists to strive for a “self-denying passivity” (121) in their work. The Romantic period is of particular interest due to the confluence and, later, the divergence of these two oftentimes conflicting epistemic virtues.

This research paper traces developing notions of the scientific self and its relationship to the practice of creating scientific images in three early science fiction novels, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896). Herein, I examine how competing epistemic virtues of truth-to-nature and mechanical objectivity bore influence on scientist’s conceptions of self and, through them, the creation of distinct, albeit vacillating, images of nature. I also look at how scientist’s internalization of such epistemological anxieties came to shape the externalizing practice of creating scientific images. The epistemic virtue of truth-to nature, which dominated scientific practice throughout the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, focused the work of natural philosophers and early modern scientists on creating reasoned images, a practice which by no means would fade passively into the annals of science.

I begin by asking how science fiction beginning in the late-Romantic period captured the very real anxieties related to the movement of science away from truth-to-nature and towards a more objective epistemic frame. I seek to relate literary developments in the science fiction novel, with an emphasis on the relationship between scientists and their creations, to how the scientist mediates the governing epistemic virtues of the era with their conception of self. I trace such developments in early science fiction texts to first define and later explore the idea of the “scientific image,” the scientist’s use of semiotics and rhetorical devices to shape an image of nature, providing a degree of critical distance between subject and object. I relate the dynamic alterations in the scientist’s image making process to an overarching anxiety regarding the movement from natural philosophy to the more rigid and decidedly modern practice of objective science that persists today.

In the first chapter, I review the historical undercurrents in science and society beginning in the mid- to late-eighteenth century. Drawing on the work of historians and philosophers of science, I assess the changing conceptions of the scientific self and their relationship to more tangible scientific practice. I first discuss the prevailing and oftentimes conflicting epistemic virtues of truth-to-nature and mechanical objectivity, with specific attention given to the period of their overlap coinciding with late-Romanticism and the publication of Frankenstein. Next, I turn to the development of the scientific self in relation to the prevailing epistemic virtues of the age, making tangential inferences between Kantian objectivity and subjectivity and its influence on emerging anxieties of the self in nineteenth century England.

In the second chapter, I propose that the creation of scientific images is a distinctly literary practice, one that began in the late eighteenth century. Drawing on the scholarship of Amanda Jo Goldstein and Tita Chico, I explore the necessity of the literary imagination and the use of subjective inferencing to conceiving and communicating scientific ideas. I next turn my attention toward the role of the metaphor in the art-science of image creation. I first suggest that the metaphor, as a device used to create scientific images, is a response to the scientist’s anxiety of creating a reputable scientific self, thereby establishing a critical distance between creator and their creation. Aligning this development with the history of changing scientific practice, I propose that the literary imagination facilitated the creation of scientific images in the age of objectivity, allowing the scientist to, at all points in the process of discovery, remain partially removed from their creations. All the while, the creation (as image), takes on a subjectively endowed position, closer to that of the reasoned image of the truth-to-nature epoch. I conclude by asking how the use of metaphor and imagery endow scientific images with meaning that is supplementary to the significance first prescribed to them by their creators.

Beginning in chapter three, I turn to the early science fiction texts of the nineteenth century to examine how the transition from truth-to-nature to mechanical objectivity is imagined by science fiction authors. In chapter three I propose Victor Frankenstein’s creature as a scientific image that speaks back, commanding, for the first time in a literary meditation on modern science, the ability for objectified nature to speak for itself and redefine its image in a rebuke of its creator. I additionally suggest that the creature is an image-of-self, created by Frankenstein as a manifestation of his anxiety towards the act of scientific creation.

In chapter four, I continue with The Island of Dr. Moreau, furthering my line of inquiry into the late nineteenth century, when objectivity became firmly rooted as the prevailing epistemic virtue of science., I analyze the incongruency between self and image, proposing that mechanized scientific images, such as the monstrosities of Dr. Moreau’s island, put scientific reason and the subjective qualities of scientific practice into question. Here, I also explore a case study of scientific communication in miniature by regarding Edward Prendick as a representation of a knowledgeable public’s response to the potentially disturbing products of modern science in anticipation of current scientific advances.

In chapter five, I briefly turn to The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (hereafter referred to as Jekyll and Hyde), where I consider Edward Hyde as an exemplification of the scientific image as self, speaking not only to his creator, but for him as well. In this case, the image serves not as a manifestation of the scientific self but, quite oppositely, comes to define the self through comparison. I conclude by examining Edward Hyde as a scientific image that fails to separate from Henry Jekyll’s scientific self, denying Hyde the ultimate goal of the reasoned image: Complete autonomy. I conclude by theorizing on the death of images and the necessity of the scientist to the image’s life.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

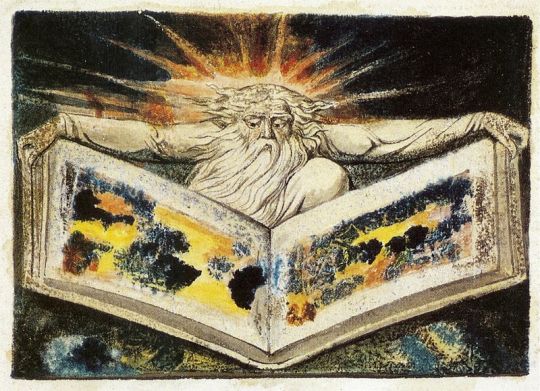

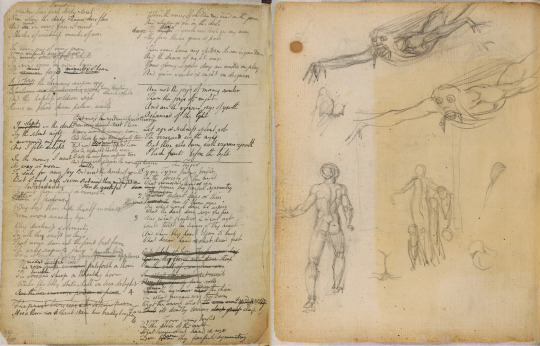

Critical Essay: “Writing the Words” by Daniel Wakelin

Daniel Wakelin, in his essay “Writing the Words,” observes that the etymology of the word text “suggests the importance of a visual impression,” (38) aptly noting that the process of textual interpretation begins long before the act of reading. When readers engage with a manuscript, they do not simply read each word and deduce it down to a single piece of information. Rather, the visual observation of the script itself precedes the logical understanding of each word’s meaning. Therefore script, as a visual form of information, bears equal weight on the reader’s interpretation of a text. When reading modern print, the textual homogeneity of the words on the page equalizes them – each word acting as an individual piece of logical information that is to be understood only in the context of the larger sentence; the sign and the signifier acting discretely to inform the reader’s understanding. In manuscript writing, however, the script takes on a dual function, acting as both sign and signifier. In this way, the text itself becomes an “image,” (44) visually bearing its own significance and acting in tandem with language to dictate understanding – one sign, two possible interpretations.

In understanding the word as an image and that image as bearing significance in of itself, Wakelin positions the question of who creates the image to be a matter of utmost importance. As an intermediary between the original author and the reader, scribes have special agency over the presentation of text; how the words look on the page, the script they choose to write in, and the rubrication of that script all being of the scribe’s choosing. Although scribes serve the utilitarian function of moving the text from one form into another, they also have the opportunity to more intimately influence the reader’s interpretation of a text, raising “questions about the complex relationship between book production and reception, for the script is not usually identifiable as an artistic choice by the author.” (44) Wakelin poses this relationship, between the “pragmatically literary” (48) author and the “more ostensibly creative” (48) scribe, as a product of their divergent roles in a text’s creation. To imagine the scribal hand as an additional creative force that influences textual production and not serving a simply utilitarian function recognizes the agency of the scribal work in a manuscript culture. Thus, “the scribe’s practices or intentions,” (37) and their effect on how text as an image is represented cannot be overlooked in any attempt to understand the history of textual reception before the printed word.

It is therefore pertinent to consider both the scribal hand and the mind of the author in textual production, each responsible for one half of the significance that each word comes to bear. Wakelin understands this realization to “reveal not just script as a visual model, but writing as a ‘dynamic’ process among, in competition with, and as a constituent part of other social and cultural processes.” (38) In the same sense that the language and subject matter of a text is reflective of the period and the ideals in which it was first written, script too, in its visually autonomous significance, can contain a wealth of cultural information. Wakelin uses the benign example of a cookbook to clarify this idea. Yes, a book of recipes can reveal a lot about what people of the time were eating, “but the informality and the haste” (45) of the script “tells us lots about the occasions for copying and reading these recipes, tips and cures: private, informal, amateurish, utilitarian, urgent.” (45) In this example, the image of text helps us to understand the social significance of cooking. Wakelin notes that the hand “oscillates haphazardly between graphs modelled on different ‘scripts.’” (45) Not only do scriptural features reveal information about the scribal hand, they also provide insight as to the working conditions of the provincial kitchen. Just as the recipes are written in haste, the food was to be prepared as such. The scribe takes an active role in contextualizing and creating supplementary meaning – the image of the text ultimately containing information that measurably bears on the text’s cultural significance.

The image of script, as it is dictated by the scribal hand, has the potential to endow a single text with multiple levels of meaning. Therefore, the significance that the scribe imparts through the creation of the textual image may or may not differ from the substance of the language as written by the author. If the author and the scribe have the same motive in both composition and inscription, the singular significance should become only more pronounced when observing and reading the text in tandem. On the other hand, if the scribe uses the visual image of text to add an additional, possibly even contrary significance, we may find an observable discrepancy between sign and signifier. Seeing that “there are also many manuscripts where spelling, punctuation, layout or the exemplar used shift visibly,” (37) while also acknowledging such inconsistencies to be “one of the most distinctive features of manuscripts,” (37) the possibility that the scribe could complicate the author’s original meaning cannot be discounted. However, I approach this idea tentatively and under the premise that scribes should not be singularly thought of as nefarious manipulators of text who set out to reshape the author’s language during the process of inscription to serve their own purposes. Yet scribes, as the people responsible for the transmittance of ideas from one form into another, will inevitably influence a text’s reception through the independent choices they make as to its presentation. Wakelin takes the same concept into consideration, paying specific attention to time as a vehicle for textual change. Time is, however, quite impossible to look back upon. Various inceptions of texts change from scribe to scribe and hand to hand and, unless such changes are explicitly documented, they are usually lost in time. This fact poses an unassailable challenge for the reader who then must facilitate their reading with the realization that the image and language of a text may, when observed in combination, yield a more complex interpretation and one not impervious to discrepancy.

For manuscript texts to be reproduced, as is done in modern print, in a homogenizing way so as to annul the image entirely and keep simply the “pragmatically literary” (48) value of the text, negates the important cultural and social information that we have previously understood the script to contain. Yet, we must alternatively consider the scribal hand as having the potential, consciously or otherwise, to pervert the intended or original meaning of text as dictated by the author. As we have learnt from the study of typology, “what determined the choice of typeface was less the time taken to set it than the sense that different typefaces suited different subjects or readerships.” (58) Wakelin attributes the progression of uniformity in texts as the product of advancements in print technology at the beginning of the sixteenth century. I suggest, however, that the intensive effort to create a printing press to increase the speed but also the precision of printed texts is the combined product of a uniquely contemporary anxiety over conformity. Though type is not without its flaws, “the scribes of English literary works were seldom engaged single-mindedly on copying texts,” (35) thus leaving room for “an amount of time over which the scribe’s hand may change in quality (be ‘not steadfast’).” (34) Rather than looking at the possible discrepancy between image and language as negatively impacting the supposed pristine form or intended interpretation of texts, we instead must regard the “not steadfast” quality of manuscript writings as an opportunity to discern an even greater abundance of social and cultural significance from manuscript works.

These realities of scribal work open the possibility that a text’s original meaning is forever distorted once copied into the manuscript medium. However, to this factor from the act of interpretation would be to neglect the all-important social and cultural history that such confounding pressures impart on a manuscript. Instead, we must embrace the dual significance of manuscript texts, where both language and image are conveyed through the word as their common symbol. Manuscripts are the product of a convergence between the literary and visual mediums – the interaction of which not only shapes the modern study of texts, but profoundly influences contemporary notions of manuscript society.

Works Cited

Wakelin, Daniel. "Writing the Words.” The Production of Books in England: 1350-1500, edited by Alexandria Gillespie and Daniel Wakelin, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 34-58.

0 notes

Photo

The Washroom

This isn’t the washroom. No. This isn’t the washroom. This is no room at all. Not a hallway, either, Really. Not even walls or floors or space to walk.

This isn’t the washroom. This isn’t a castle or a dream There are no clouds here, no Sound, no light, no air. My mothers are not here, I wonder what those rooms look like where they are.

This isn’t the washroom, What does a washroom even look like?

This, whatever It is, Is not the washroom. Here I am dirty and waiting for salvation, I Pray to unnamed gods whom I refuse to believe in, In a place refusing to be believed.

I bite my tongue.

This isn’t, however, the washroom. The women are nowhere to be seen, Their perfumed brushes sitting Useless in thin air.

This isn’t the washroom. If it was there would be life here, Maybe answers, maybe not, But in any case, there would probably be a sink.

This isn’t the washroom, there are No needles, no blood – it is dark however And maybe I just can’t see them.

If this were the washroom and I, Had found that fateful door, I’m sure the tub would be full of hot cold water And fresh towels, placed by the maid to be dirtied.

The washroom was on the right they said. And I went left because they are known to lie.

Maybe they don’t want me to find it, The washroom. Maybe they keep it locked for a reason And Maybe, maybe they hand you the keys for only the idea of relief.

0 notes

Photo

On Reading Bruno Latour’s Politics of Nature

Written in preparation for an independent research study.

June 15, 2020

Society and Nature, Humans and Nonhumans

We emerge with Latour, in the Politics of Nature (2004), onto a fractured landscape, a systemically broken nature-culture where modern conceptions of politics and society are completely cut off from objectified nature. Yet, Latour argues, it is this same limiting binary between the natural object and the human subject that upholds modern Western civilization. Latour identifies a widespread fear, embedded within what he refers to as the “Old Constitution,” of the potential consequences of unifying these two distinct entities:

Without this division between ‘ontological questions’ and ‘epistemological questions,’ all moral and social life would be threatened. Why? Because, without it, there would be no more reservoir of incontrovertible certainties that could be brought in to put an end to the incessant chatter of obscurantism and ignorance… Nature and human beliefs about nature would be mixed up in frightful chaos. Public life, having imploded, would lack the transcendence without which no interminable dispute could end (12).

What Latour initially describes is the Cartesian distinction between that which is natural, the finite and definite objects of nature and that which is non-natural according to the Old Constitution – the interpretive world created by a subjective humanity. Within the Old Constitution, scientists alone have access to nature through the supposedly objective lens of experimentation. Society, which includes the politicians, moralists, economists, and laymen, alternatively compose for themselves a subjective world, where the nature of things can only ever be understood through interpretation and what the Godhead of Science allows to enter the realm of society. Within Latour’s Old Constitution it is not that the scientist and their society are enemies – it is just the opposite – they have been operating for thousands of years under the guise of camaraderie. Rather, Latour’s characterization of scientists and society positions them as foreigners in each other's lands, unable to speak the only language either knows.

It is exactly this binary between the natural object and the human subject that Latour first takes issue with. It is to what he attributes humanity’s current stalemate within the ecological crisis. He argues that it is “under the pretext of protecting nature” (19) that the contemporary ecological movement simultaneously retains a “conception of nature that makes their political struggle hopeless” (19). Under the Old Constitution, “‘nature’ is made…precisely to eviscerate politics, one cannot claim to retain it even while tossing it into the public debate” (20). If we choose to prescribe to Latour’s logic, it will forever be impossible for society to address the ecological crisis while the notion of a social-natural divide, as posed by the Old Constitution, remains implemented. Latour’s idea of an ecological crisis extends beyond global warming or greenhouse gas emissions. Western society’s troubled relationship to the earth extends deeper into the epistemological and ontological questions that the Old Constitution fails to adequately address. So long as there is an externalized nature that exists outside the internal social realm, so long will this abusive relationship continue. Social issues cannot be addressed using facts endowed with truth by the natural sciences alone. Nor can scientists remain the sole proprietors of truth, who enter the forum in an act of quasi-divine profession to only then excuse themselves entirely and leave society the responsibility of interpretation.

Latour begins to repair this fractured landscape through a re-categorization of what forms of knowledge emerge from “Nature” versus those which emerge from “Society”. In true Latourian fashion we must affix quotations to these words because they now fail to bear any meaning. If we wish to move away from the limiting confines of the Old Constitution, we must first accept that the nature-society divide is fabricated on an outdated system, a system first proposed by the early moderns so that they could claim to understand everything “Nature” or “Society” had to offer.

What Latour presents in the Politics of Nature is a restructuring of this relationship. It does not dissolve the barrier completely, but rather shows that the modern’s terms “Nature” and “Society” are much more mutable than previously thought. In fact, within the Old Constitution, they mutually come to define one another. The great fault in this binary is that one cannot exist without the other. There is no external nature without a society to which it is internal and to which it surrounds. This poses the immediate epistemological problem that both cannot coexist within the same framework, where one always takes supremacy over the other. “Science” will always retain a claim to “facts” and “truth”, while “Society” is left to quibble with the interpretation of such facts. Furthermore, any decisions that society may make through the process of interpretation only ever appear in relation to the immutable truths of the former. If we conclude that nature is real, social systems at once disappear, they become inoperative agents in any unified world we try to create. Latour describes this as an “ecological crisis,” (65) though not in the contemporary sense. Most crises of this kind “arise from a process of inscription by the sciences, a process in which the only disciplines capable of alerting us to the problems put them into words, sentences, and graphs—but to acknowledge as well that these same sciences no longer suffice to reassure us about the solutions” (65). If the social world is always reduced to matters of concern and the scientific world always to matters of fact, then society (scientists included) are always free to disregard concern for the cold, hard truth of scientific reason. When relating these same ideas back to the ecological crisis of the contemporary variety, the kind where the Earth and everything on it are doomed for a fiery death, then the apparent limitations only further limit our ability to act. How can scientists and society ever work together to address the ecological crisis when they are speaking different languages? Furthermore, even if we somehow equalized this language barrier so both could speak on the same terms, one will still retain a claim to external validity while the other is reduced to the frightful realm of mere ideas.

Latour’s decisive breaking point from the Old Constitution becomes a matter of using semiotics to do away with the nature-society binary. He poses the creation of two new classes of categorization that he insists transcend the old system: humans and non-humans. At first, I was wary that any change in semiotics had occurred. “Human”, to me, seemed to be synonymous with the Old Constitution’s “Society”, a uniquely human construction. Similarly, “nonhuman”, I supposed, was a term that still grouped natural objects together, though now only relationally to the human subject. I think the notion of relativity is important to consider here, however, because it may actually, to Latour’s credit, bring us one step closer to closing the binary gap. In Latour’s “New Constitution” there is less separating the human subject from the natural object; humans and nonhumans are, semantically, already more similar than “Nature” and “Society” ever were. What now separates humans from nonhumans is the idea that nonhumans are not us, they are exactly what they are called – not human. This does not however mean that they are the same rigid, law abiding, static entities they once were when they belonged to the category of “Nature.”

Whereas “Nature” was external, nonhumans can co-inhabit the same epistemological space as humans do. Thus, the questions we ask of either no longer must be asked separately. As Latour states:

Let us remember that nonhumans are not in themselves objects, and still less are they matters of fact. They first appear as matters of concern, as new entities that provoke perplexity and thus speech in those who gather around them, discuss them, and argue over them. (66)

By redefining the natural world as a relational concept in the New Constitution, it finally ceases to be external to humanity. Nonhumans can be spoken about by all humans unlike how “Nature” could only be spoken about by scientists who, in reality, were always just humans masquerading as Gods. “Instead of an absolute distinction, imposed by Science, between epistemological questions and social representations,” the terms nonhuman and human present “a fusion of two forms of speech that were previously foreign to one another” (67) Simply, objects and subjects [could] never associate with one another; humans and nonhumans can. As soon as we stop taking nonhumans as objects, as soon as we allow them to enter the collective in the form of new entities with uncertain boundaries, entities that hesitate, quake, and induce perplexity, it is not hard to see that we can grant them the designation of actors. (77)

Now, humans and nonhumans can not only speak on the same terms but can equally play a part in the determination of social actions, both being social actors; “Associating social actors with other social actors: here is a task that is already more feasible, one that nothing forbids us to accomplish” (77). Within the confines of the Old Constitution, “Science” was the sole possessor of the claim to reality. In the old framework it was easy for the scientist to dismiss the other parts of collective society for the reason that empirical wisdom - science’s best strength and most limiting weakness - was the only method of deciphering fact from fiction, what is real from what is constructed. Now, with the designation of nonhuman, natural objects are free to speak for themselves through the collective. No longer are scientists the only translators of a mute Nature. In the New Constitution any phenomena which is perplexing can be presented as a matter of concern and enter the public forum where then scientific reason, ethics, morals, and values can all be applied to it equally. By expanding the set of tools by which they can understand the nonhuman world, humans agree to enter into a dialogue with their nonhuman counterparts. Knowledge is no longer separated into two distinct houses and neither house can squander the ideas of the other on the basis that they alone have access to universal truths. Now, everything is possible when a nonhuman appeals itself to the public forum. No truths are decided upon prior to the point where all humans – scientifically minded or otherwise – greet the nonhuman with open minds.

One might ask, as I surely did, what we might lose by signing in this New Constitution. “If we cannot determine objective truths using the tools of modern science,” the critics will say, “then we cease being able to independently verify nature without the corrupting influences of society.” Yet, Latour has an answer for this as well, one which dually reveals the central fallacy upholding modern science:

By limiting themselves to the facts, the scientists keep on their side of the border the very multiplicity of states of the world that makes it possible to form an opinion and to make judgments at the same time about necessity and possibility, about what is and what ought to be. (98)

In the Old Constitution, one major strength of science is that it did not have to consider values when professing found truths because facts were essentially valueless. For a time and in some select disciplines this dogma did suffice. There is a significantly lower appeal to ethics in Newton’s laws of motion than there is to, say, divesting in fossil fuels. The issue with modern science, and thus the entire nature-society binary of the Old Constitution, is that the scientist could remain relatively neutral in situations that otherwise demanded sustainable ethical or moral attention. Stating as a matter of fact that the burning of fossil fuels is responsible for global warming is very different from the value that would say burning fossil fuels is morally wrong. This latter value could never be proved by the tools of science because the old “Science” did not operate within the realm of right and wrong, but in an alternate universe where there were only ever valueless facts. Values were applied retroactively to the sciences not by the scientists themselves, but by economists, moralists, and politicians, who together compose the vast majority of the collective. This system perpetually short-circuited our ability to act on the facts which scientists presented because the values we chose to place on them never had the same epistemological value.

The Moralist and the Scientist

I now turn to two of the roles Latour specifically alludes to in the Politics of Nature as equally responsible for reconstituting the Old Constitution in order to usher in the New. In the New Constitution, the prior “sins of pride and arrogance that scientists commit in the name of Science become civic virtues…in the search for wisdom by offering to recombine the habits of the propositions submitted to collective examination” (139). In Latour’s new framework, the scientist would no longer be the only part of the collective bringing matters of fact to table. Rather, they would account for just one facet of how matters of concern would become matters of fact, or, in the terminology of the New Constitution, how the perplexities of nonhumans are consulted and thus “instituted… as a legitimate presence at the heart of collective life” (107). Whereas in the Old Constitution:

Scientists had to be constantly punished for their arrogance by being dragged back to the prison of the laboratory and forced not to look higher than their own pallet. We have done the inverse: far from criticizing the sciences, one must on the contrary respect the diversity of their skills, allow the variety of their qualities to be developed, their indefinite contributions to the composition of the common world to unfold. (142)

By defining this new role for the scientist, “there is no need, either, to imagine a ‘metascience’ that would be more complex, warmer, more human, more dialectical, and that would allow us to ‘surpass the narrow rationalism of the established sciences’” (142). Dialogue between facts and values would not have to be an internal product of scientific discourse between a limited number of actors, but a product of collective discussion. The scientist is now relieved of the burden of having to do everything at once. They no longer need to worry about remaining objective and impartial, because that is no longer their job in the first place. As soon as we stop demanding scientists to only speak in the cold, isolated language of facts, the sooner they can enter the collective and begin to make equal contributions to the discourse of reality; “Let us restore to the sciences the crush of democracy from which they were supposed to have been protected as they grew” (143).

The second of the four roles that Latour outlines, is that of the moralist. In the framework of the New Constitution, “moralists add to the collective continual access to its own exterior by obliging the others to recognize that the collective is always a dangerous artifice” (157). Through the moralist, the collective always remains cognizant that intuitions can never again slip into the precarious realm of facts:

Without the moralists, we would risk seeing the collective only from within; we would end up reaching agreement at the expense of certain entities that would be definitively excluded from the collective (157).

Whereas the scientist asks what can be known, the moralists asks, what cannot be known or rather, what do we not yet have the tools or insight to fully qualify. Such is the difference between an environmental scientist and an environmental activist, though these categories are not mutually exclusive. Whereas the environmental scientist can only ever ask Nature to reveal itself through experimentation, the activist can imagine a better, more sustainable future regardless of what the facts permit. The best environmental scientists may well be environmental activists who work toward both better understanding nonhuman elements as well as vouch for humanity’s most sustainable interactions once that understanding has been collectively instituted.

I harken back to Latour’s terminology and his theoretical frameworks because I find this epistemological repositioning of what knowledge constitutes our reality both liberating to the new environmental movement and to accessing the role which poetry may play in bringing about this transformed understanding. For what Latour does to nature by constituting it as a social actor, equal in relevance to humanity, is what I feel the best of the ecopoets achieve in their work. I think it would be to my advantage to use Latour’s terms, human and nonhuman, when reading ecopoetry to better understand how the poet’s use of sentiment, the subjective voice, figurative language, and narrative, help to refigure the limiting conceptions of nonhumans imposed by “Science” of modernity. I wish also to use Latour’s roles of the scientist and moralist to ask how the ecopoet may play both parts at once and furthermore ask how ecopoetry may function as a sustained dialogue between established facts and moral values. Do literary devices and the use of sentiment in poetry help close the binary between science and society by making society imagine themselves as an object of science? If so, can ecopoetry be the cornerstone of Latour’s collective forum where groups of social actors and actants join in dialogue on equal ground? Latour presents many other interesting new terminologies that I believe constitute literary devices including “quasi-objects,” which are neither wholly objects of science nor subjects created by society, and the formation of “networks,” interacting groups of quasi-objects.

I wish to investigate how ecopoets go about drafting these quasi-objects and networks in their work and, additionally, ask if these terms constitute new literary devices employed by environmental poets to present new modes of understanding ecological crises in both the Latourian and contemporary sense. Furthermore, I wish to explore how the role of the ecopoet as a communicator of science may be essential in helping to bridge the nature-society divide. In regard to how scientific matters of fact are rendered into social matters of concern, Latour, in We Have Never Been Modern (1993) suggests that there are two types of translators. The first is “an intermediary,” who, “although recognized as necessary, simply transports, transfers, transmits energy from one of the poles of the [Old] Constitution” (77). The second type of translator Latour calls a “mediator… an original event [that] creates what it translates as well as the entities between which it plays the mediating role” (78). I wish to analyze these two categories in regard to how different ecopoets take on the role of intermediary or mediator in their work. Must a successful ecopoet act as a mediator? Are all unsuccessful attempts at communicating science as such because they function on the level of intermediation as opposed to mediation? Is the notion that intermediation can suffice when translating scientific understanding into the social realm a uniquely modern idea, and thus condemned to the same rigid binarization as the Old Constitution? To what degree does ecopoetry and the role of the ecopoet answer the call of Latour’s New Constitution, where, once implemented

there is indeed a nature that we have not made, and a society that we are free to change; there are indeed indisputable scientific facts, and free citizens, but once they are viewed in a nonmodern light they become the double consequence of a practice that is now visible in its continuity. (140)

If ecopoetry fills this role through the use of a new generation of environmentally inspired literary devices, the ecopoet gains “a capacity for sorting and recombining socio-technological imbroglios,” (141) and thus the ability to “reconstitute the social bond” (142) between humans and nonhumans.

Works Cited

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter, Harvard University Press, 1993.

—. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Translated by Catherine Porter, Harvard University Press, 2004.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Woman in the Window: An Entrapment of Feminine Identity in the Domestic Home

“The Yellow Wall-Paper” (1892) by Charlotte Perkins-Gilman recalls one woman’s descent into madness from within the confines of her country manor. Gilman’s story further pervades into ulterior external spaces which reimagine the domestic household and its surroundings as a prison of feminine individuality. In “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” the narrator interacts with the external environment by peering through windows, the contents of which challenge her perceptions of reality. The fear she encounters due to her domestic confinement finds reaffirmation in the world she imagines beyond her windows, suggesting that from her internment, the domestic sphere expands to encapsulate all aspects of the narrator’s perceivable reality. Although the narrator's depictions of herself exist in singular relation to the domestic space, they encompass a physical space beyond the confines of her room. As the narrator’s mental state diminishes, so does her perception of reality, confusing ideas of how domestic space can shape the world beyond the confines of her home. The images she sees beyond her windows act as emancipatory symbols: External embodiments of her longing to escape, yet also as contradicting figures of ridicule, further defining her limited agency in the gendered world which imprisons her. As Gilman’s narrative progresses, the home becomes increasingly indistinguishable from the narrator’s character. In “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” windows signify the expansion of the domestic rather than an aperture admitting air or light. Rather than allowing access to an external world, windows counterintuitively externalize the narrator's feelings of confinement, ultimately projecting and extending the home and its accompanying patriarchal discourse beyond the interior space that appears to bind her.

In “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” Gilman’s narrator engages with her surroundings through her interactions in the domesticated room and in the viewing the external environment from her window. From these interactions emerges a discourse between the two spaces; their communication distorting the separation of the public and private spheres. This dialogue eventually leads to the narrator being unable to distinguish either space, thus losing herself to an overpowering home. William C. Snyder in “The Yellow Wall-Paper as Modernist Space” identifies the two visual frames which materialize in the narrator’s writings: “(1) the windows out of which the woman can enjoy the pastoral spaces beyond the house, and (2) the wall, an antinature, two-dimensional “canvas” on which she ends up “painting” with emotion, anxiety, and obsession” (Synder 76). However, Gilman’s narrator has a more weary relationship to the windows in her room, one which extends beyond interacting with them to simply view pastoral landscapes.

At first, her interactions with the external environment may seem benign. From one window she “commands the road, a lovely, shaded, winding road, and one that just looks off over the country. A lovely country, too, full of great elms and velvet meadows” (Gilman 847). Initially, Gilman builds suspense by articulating a seemingly pleasant relationship between the narrator and the outside world. More so, this external world momentarily exemplifies ideas of female emancipation. The windows present a liberating counter-space to interior walls she views with increasing dread: “I am sitting by the window now, up in this atrocious nursery, and there is nothing to hinder my writing as much as I please” (Gilman 846). Here, the sights beyond the window, present a redemptive contrast to the confines of the room. However, as her hysteria progresses, the domestic space expands outward. The images which first plague her within the confines of the room, now materialize in the external environment.

As nature turns on her, the windows offer a vantage point to the shrinking external world, representative of the restraints that domesticity forces upon her. Using the motifs of light imagery, Gilman makes use of an observable natural phenomenon – the light of the moon – to suggest the encroachment of the external scene, like wall-paper of the room, upon the woman. She notices for the first time the moon and how it “shines in all around just as the sun does. I hate to see it sometimes, it creeps so slowly, and always comes in by one window or another,” (Gilman 849) and therein summons an overwhelming feeling that the moonlight is infringing upon her individuality. Alike to the wall-paper, which is interminably “grotesque,” the moonlight, which is seeps in from the windows, adds to her state of dismay. The narrator, watching “the moonlight on that undulating wall-paper” until she feels “creepy,” gives her a first sense that no space, whether inside the room or in the external environment is safe. Instead of the pleasingly pastoral pictures the windows once brought her, the narrator succumbs to her hysteria, projecting onto the external environment the same fear she harbours over her confinement to the home. The universality of this view renders the narrator helpless, her one solace slowly diminishing before her eyes. As Snyder’s idea of the pastoral window fades, the “new” windows, and the sights they behold, further restrict the woman to her domestic imprisonment.

The exterior space, now acting to reinforce her domestic confinement, blights any possibly of her liberation from the home. From the narrator’s imagination emerges commonalities between internal and external images of captivity. As her observations become more vivid, more definite in their ability to induce hysteria, the steeper the narrator’s descent into madness becomes. The breakdown of the narrator’s ability to distinguish reality from fantasy materializes in the identical female figures she sees in the room, and then later through her windows. Initially, the narrator metaphorically attributes the patterns of the wall-paper to the female form, “like a woman stooping down and creeping about behind that pattern.” As the narrative progresses, however, figurative language gives way to deceptively “real” women, who “creep” about the narrator’s mind as they transverse the interior space of the walls. (Gilman, 849) Deborah Madsen comments on the breakdown of sense in the narrative, as it “questions the decipherability of the external physical world, basic categories of perception break down: real versus fantasy, living versus dead, actual versus imaginary, friend versus foe” (Madsen 84). Madsen’s theory allots the collapse of reality foremost to the figures which protrude from the walls. The windows, to which the narrator’s visible metaphors eventually extend, suggest the breakdown of perception as the manifestations become physically limitless.

In accordance with the outward expansion of the home, the narrator begins to project the ghosts of domesticity – visceral representations of her gendered state – onto the external environment. In confidence with herself, the narrator admits that “privately—I’ve seen her! I can see her out of every one of my windows” (Gilman 853)! As the images begin to coalesce within the narrator’s mind, the pace of the narrative increases. The woman, who, more desperate than ever to escape the ghosts of domesticity, turns to her window for solace, instead, and to her horror, finding a reaffirmation of her confined state. This instance represents another externalization of the narrator’s confinement – yet this time it is her own perception, embodied within the windows, which defies her. Here, Gilman suggests the gendered nature of the narrator’s affliction. Owing to the fact that it is other women, or more so, her perceptions of other women that abed her confinement, Gilman insinuates the dissociation of the domesticated woman from society. To view the home as a traditionally feminine space, only to have figurative women invade the house from the outside, metaphorically pits the narrator against herself. In this sense it is the women from the window who, like the narrator’s husband, restrict femininity to the domestic sphere.

The windows themselves, once thought of as a medium of refuge, now propel the narrator further into madness by reflexively displaying back to her the restrictive images of her depleting conscious. Gilman achieves her narrator’s isolation through an inversion of how readers traditionally view the symbol of a window. Architectural theorist Bechir Kenzari defines what he believes to be a shared understanding of the window’s symbolism:

The window provides the narrator/dweller with this privilege of knowing him or herself as other, through the perception of a common belonging expressed by the opening of a shared human space… The narrator/dweller is no longer an active sender but a passive receiver; and conjointly, the window no longer appears as place located ‘there’, but a place of reception located ‘nearby.’ (Kenzari 43)

Instead of allowing the narrator to escape through the frame of the window, Gilman uses the window to isolate the narrator from the outside world, and in doing so, defies Kanzari’s ideas of “shared human space.” Though the narrator remains a “passive receiver,” which contributes to her depleting agency, the “nearby” locality that windows typically provide is hyper-actualized. The nearness of her hallucinations becomes so close as to manifest themselves within the domestic space the narrator is trying so desperately to escape. Additionally, Gilman denies her narrator a “perception of a common belonging,” as the sights she views from her window only further reinforce the “otherness” of the female condition – the isolation of the mad woman within her home. For the narrator, the window is not a “‘recreating’ virtue that could be closed and opened at will,” (Kenzari 43) but an obstructive object which symbolizes her entrapment.

The prison-like nature of the domestic window takes on a visceral representation in the text. The windows, “barred for little children,” (Gilman 845) both demean the narrator, treating her as a child who lacks agency over her entrapment, as well as take an emancipatory symbol and distort it beyond its traditional meaning. Again, invoking light imagery in the natural scene, “the lamplight, and worst of all by moonlight, [they] become bars! The outside pattern I mean” (Gilman 851). From this perspective, it is not the windows alone that demonize receptacles of light; the placing of bars on the windows contort images of sanctity into reminders of her insanity – the bars turn the moon’s light into a reminder of the “patterns” which the narrator fears. The moonlight “becomes bars;” the only way for the narrator to observe the external environment is though the barred window. Therefore, all the images which the narrator views from her windows invoke feelings of confinement, whether they themselves represent her imprisonment or not. Like the internment of the narrator herself, the windows trap images of the external environment in the home. The images of the domestic sphere construct the narrator’s perception of herself, tying it intrinsically with the physical house and, ultimately, extending the limits of the home beyond interior spaces.

Gilman reimagines both interior and exterior spaces as places for the confinement of the female form. More explicitly that the expanding domestic sphere can overtake the external sphere which lies beyond its walls. The gendered nature of the narrator’s internment only exacerbates her affliction. The effigies of “creeping women,” which are she views though the already confining visual frame of the window compound upon one another, until, to the detriment of the narrator, the images overpower her waking mind. In trying to view the hordes of creeping women, the narrator spins about her room, the windows providing the visual frame from which her confinement externalizes:

“I often wonder if I could see her out of all the windows at once. But, turn as fast as I can, I can only see out of one at one time. And though I always see her she may be able to creep faster than I can turn! I have watched her sometimes away off in the open country, creeping as fast as a cloud shadow in a high wind.” (Gilman 853)

Imitations of women, who represent an external-self, overpower the narrator’s view and invade all spaces, both exterior and otherwise, that the narrator uses in her attempts to defy capture. Unable to “outcreep” the shadows protruding from the barred windows, the entire weight of the scene falls upon the woman in her hysteria. As a woman, the narrator must passively bear witness to the devouring of her sanity from a state of confinement she lacks the agency to change.

“The Yellow Wall-Paper” disrupts the traditional image of the women’s place in the home by taking to the most extreme the repercussions of confinement to the domestic sphere. Gilman suggest this confinement to be all consuming, both from within the home and from the external spaces that the captive woman can view. Windows, which once provided a redemptive Eden for the enclosed mind, slowly pervade inward, collapsing the external environment into the domestic space and thereby cornering the woman to the space of her bondage. From a place of limited agency, the woman, becomes metonymous with the home, an indistinguishable entity from the walls and other fixtures of the domestic sphere. From a state of confinement, windows become mirrors: Reflective panes which hurl backward an image of isolation in the feminine form. In place of levity, windows come to represent the gravity of the narrator’s affliction, contorting landscapes until they become unrecognizable. With an outstretched arm, the narrator grasps for the outside world only to have the window slam definitively shut – the final aperture closing – to leave a lone woman shroud in the darkness which is her waning mind.

Works Cited

Kenzari, Bechnir. “Windows: Architecture and the "Influence" of Other Disciplines.” Crossing Boundaries vol. 3, no. 1, 2005, pp. 38-48.

Madsen, Deborah. “Gender and Work: Marxist Feminism and Charlotte Perkins Gilman.” Feminist Theory and Literary Practice, 2000, pp. 65-93.

Perkins-Gilman, Charlotte. “The Yellow-Wall Paper” The Norton Anthology of American Literature: vol. C, 9th ed., edited by Nina Baym, W.W. Norton and Co., 2003, pp. 845-853.

Snyder, William C. “’The Yellow Wall-Paper’ as Modernist Space” Charlotte Perkins Gilman and a Woman's Place in America. edited by Jill Annette Bergman, The University of Alabama Press, 2017, pp. 72-93

0 notes

Photo

“For Reason is but Choosing”: Choice and Female Autonomy in Paradise Lost

The sole female characters of Paradise Lost, Eve and Sin, physically originate from within the bodies of men, situating both women in a position of implicit inferiority as a derived “part” of the male “whole”. The latent hierarchy that exists between Eve and Sin and their progenitors - Adam and Satan - is one defined by gender divisions that give men primacy over the female body. Adam and Satan negate female agency by reinforcing the gender hierarchy implicit to the formation narrative. However, the women of Paradise Lost challenge the notion that their physical formation renders them forever subordinate to their male source. From the moment of their inception, Eve and Sin confront the fact that their agency, as beings derived from the body of another, is not wholly their own. Instead of submitting complacently to the desires of Adam and Satan, Eve and Sin make choices that individuate them from their male counterparts. First physically separating themselves from Adam and Satan, Eve and Sin are afterward free to make the choices which ultimately subvert the repression of their autonomy. The ability of Eve and Sin to act as individuals defies the implications of their parallel formation stories and point to a woman’s ability to choose as a means by which she can reclaim her autonomy.

In Paradise Lost, there is an indivisible link between characters’ ability to choose freely and their degree of autonomy. God first notes this connection which develops into a mechanism within the text by which Eve and Sin eventually come to realize their autonomy. As God makes clear, the freedom to choose is one way for a creature to differentiate themselves from a creator to whom they physical being is explicitly joined. Adam is separate from God, formed in his image, but free to reason for himself. God makes this distinction before Adam’s inception in order to hold the human couple wholly culpable for eating the fruit of the forbidden tree, the original sin of mankind: “I made him just and right, / Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall” (PL. 3 99-100). God’s words define an essential method by which a creature may liberate themselves from the implications of a physically binding relationship such as that between Adam and God and Eve to Adam. Adam’s autonomy is proven when he falters and chooses to eat the forbidden fruit, proving that God, though his maker, has little control over his autonomy. The position God takes on free will foreshadows how characters eventually depict they possess autonomous agency: the determining quality which separates a creature from their creator. The creator may be responsible for helping to form the material creature but, if the creature exhibits free choice, the creator cannot ultimately be held accountable for their actions. Milton makes clear in “Areopagitica” that when God bestows upon Adam reason, he explicitly gives him the “freedom to choose, for reason is but choosing; he had bin else a meer artificiall Adam, such an Adam as he is in the motions” (Areopagitica 1010). Although God first forms Adam, it is reason and choice which define Adam’s autonomy from his creator. The relationship which Adam shares with Eve, and Satan with Sin, follows a similar structure, leaving space for both women to establish their autonomy by engaging in free choice.

Acting to prove their autonomy is not initially easy for Eve and Sin because of the implicit constraints of their physical association to Adam and Satan. From the moment Eve and Sin are formed they recognize their autonomy yet encounter limitations in their ability to make independent choices. At first, Eve does not perceive rational choice as essential to her functioning as an autonomous individual – she is submissive not because she is inherently so, but because she is taught to associate compliance with the purpose of her physical formation. The close physical association between Adam and Eve is a fact Eve cannot easily overlook because so many of her conversations revolve around her physical relationship to Adam. Initially Eve is self-reflective, showing signs that she recognizes her individuality such as when she views herself with intense interest in the water of the lake. God disturbes Eve’s first moments of introspection when he reminds her of her physical bond to Adam and her purpose in Eden. Eve would have been able to continue her exploration of self “had not a voice thus warnd” her (PL. 4 467) and brought her to Adam. It is the word of God which returns Eve to the “soft imbraces, / [of] hee Whose image thou art” (PL. 4 471-472). A docile version of Eve emerges only after she is told by God to embrace Adam. Eve’s greatest barrier in recognizing her autonomy is the idea that she must remain submissive to Adam, a notion God reinforces when emphasizing aspects of the formation narrative that frame her as physically inseparable from Adam. She goes on to repeat God’s words to Adam, telling him that it was for him she was formed, “And from whom I was formd flesh of thy flesh, / And without whom am to no end, my Guide / And Head” (PL. 4.441-443). Eve negates her autonomy by focusing on her physical association to Adam, calling him her “head,” the part of the body responsible for making decisions. Eve is blind to the ways in which her and Adam are unalike because she is constantly reminded of a formation story that promotes their likeness. Adam continues to encourage Eve’s submission when he praises her for delighting him with “both her Beauty and submissive Charms,” (PL. 4.498) physical, and often feminized qualities that purportedly support her obedience. The various degrees by which Eve is isolated from her ability to choose reflects negatively on her perception of self. Without the ability to engage in choice, Eve remains reliant on her physical connection to Adam, relinquishing her autonomy and gives herself up to “meek surrender, half imbracing leand / On our first Father” (PL. 4 494-495). Eves close physical association to Adam continues to remain a barrier by which she fails to fully recognize herself as an autonomous individual. It is not until Eve physically separates herself from Adam that she is able to make the choices which come to define her autonomy.

Sin too falls victim to the close physical association that binds her to her parent Satan, but sooner than Eve finds the opportunity to engage in choice, thus seeking out her independence. The relationship between Sin and Satan differs from Adam and Eve’s because Sin was never meant to act as a companion to Satan, yet her formation from his head nonetheless puts her in a submissive position to her male originator. Sin’s perception of self is shaped by Satan and his male angels who neglect her right to give purpose to her own life, instead dictating her purpose to her:

At first, and call'd me Sin, and for a Sign Portentous held me; but familiar grown, I pleas'd, and with attractive graces won The most averse, thee chiefly, who full oft Thy self in me thy perfect image viewing (PL. 2.760-764)

Satan initially ostracises Sin and forces her to appeal to his perverse sense of vanity in order to gain his companionship. For Satan to recognize Sin as his own, she must submit to him and does so by embracing their physical likeness. In this sense, Satan conditions Sin to accept their physical bond as the sole evidence of her self-worth, preventing her from choosing an individuality separate to his own. As such, Sin is made to suffer for their association. Satan’s loss against God’s army in heaven condemns Sin to “the general fall” (PL. 2 773) of the devils into Hell. Sin suffers dearly because she is unable to choose for herself an identity separate from her Father, forcibly made to accept her lineage and the repercussions of her physical bond.

Yet, when given the opportunity to express her agency, Sin proves that she can reciprocally command Satan to gain power in their relationship. God grants Sin the key to heaven, placing her in a position of authority over her father. Authority, for Sin, is equivalent to gaining her autonomy, because it gives her the ability to make choices – primarily the choice of whether to allow Satan his escape from Hell. Sin makes clear that this choice is one which gives her autonomy over her parent, subverting her previously inferior position:

this powerful Key Into my hand was giv'n, with charge to keep These Gates for ever shut, which none can pass Without my op'ning. (PL. 2. 754-757)

Previously unable to dissociate herself from her physical connection to Satan, Sin’s newfound power contrasts her original need to appeal to their common countenance. Satan, keen to recognize their mutual, “dire change” (PL 2.820) accentuates how Sin, in gaining the power of choice becomes independent, if not only in appearance, then also in her ability to act autonomously. Sin makes use of this power to reposition herself in respect to her formation story. No longer must she reside in the location of her creation, at the “left side” (PL. 2.755) of Satan’s body. Upon her return to heaven, Sin ensures she “shall reign / at thy right hand” of Satan, “voluptuous, as beseems / Thy daughter and thy darling, without end” (PL. 2.868-870). Sin reclaims agency over her body by repositioning her association to Satan into one that better fits her newfound autonomy. Accentuating their common physical bond, once the cause of her submission, Sin derides Satan for his ignorant suppression of her individuality. No longer a simple “part” of Satan, Sin is now also an essential part of his plan, without which Satan cannot rise to Eden. Satan suffers for his previous abuse of Sin as she holds him accountable to their physical connection – the same connection she remembers to have been the cause of her submission. All the while Sin retains her autonomy because she is no longer acting from a position of inferiority. Sin’s reimagines her association to Satan subverting her position of submission to one defiance, proving that the ability to exert power through choice can reclaim feminine agency from a narrative which first sought her oppression.

Eve, however, is not immediately able to defy the implications of her formation from Adam. Remaining submissive to his choices, Eve must reason with Adam to achieve her physical separation. Eve uses Adams characterization of her capacity to reason and makes use of the same sentiment when justifying to Adam the purpose of their parting:

Let us not then suspect our happie State Left so imperfet by the Maker wise, As not secure to single or combin'd. Fraile is our happiness, if this be so, And Eden were no Eden thus expos'd. (PL. 9 337-341)

Eve convinces Adam that their free state within the garden is dependent upon their ability to act individually, a state of being which also requires their departure from one another. Adam grants her request, insisting it is possible for Eve to avoid Satan’s corrupt influence if she employs reason, “for what obeyes / Reason, is free, and Reason he made right” (PL. 9 351-352). In convincing Adam to allow her departure, Eve takes the first step toward the redemption of her autonomy. Inadvertently, Adam also recognizes how the formation of Eve and therefore the close physical association between them limits her ability to act freely because it adjunctly limits her ability to reason for herself. He tells her to “Go; for thy stay, not free, absents thee more; / Go in thy native innocence, relie / On what thou hast of virtue.” (PL. 9 372-374) Eve’s physical separation from Adam is a pivotal moment in her development as an autonomous individual. When Eve remains close to Adam her freedom is not entirely of her own choosing, she must ask and have choice granted to her. The isolating of the couple from one another creates the necessary physical diversion from the implications of Eve’s formation so that she may realize her ability to choose, a power which, until their parting, Adam retains over a submissive Eve.

Finally having part from Adam, Eve sets of into the wilderness of Eden, free to exercise choice and, in doing so, prove herself completely autonomous. The paramount moment of choice for Eve is also the climactic moment of Paradise Lost. Satan and Eve’s extended dialogue before she consumes the fruit of the forbidden tree places feminine choice as a decisive turning point in the text, one which has ramifications for all of mankind. Up until this point, Eve’s choices were largely made for her by Adam or dictated by God. Not only does Satan tempt Eve with knowledge, he also offers her the ability to choose. As Eve has previously and expressly sought her autonomy Satan’s advances on Eve become all the more tempting for the nascent autonomous individual – a cumulative opportunity to prove she is capable of self-determination. Satan, listing the many reasons that eating the fruit would be of benefit to Eve, ends his appeal saying that “these and many more / Causes import your need of this fair Fruit. / Goddess humane, reach then, and freely taste” (PL. 9.730-731). Appealing to Eve’s inherent desire for individuality, Satan presents Eve a choice that is all her own. Eve’s response to the serpent further stands to support her autonomy because she does not immediately reach for the fruit but first reasons with herself in a series of astute rhetorical questions on the nature of humanity’s purpose and human mortality. Thinking for herself Eve notes that nothing “hinders then / To reach, and feed at once both Bodie and Mind” (PL. 9.778-779). By recognizing her freedom to act, Eve completes her development as an autonomous individual. Regardless of the ill repercussion of her actions, it is undeniable that Eve’s decisive choice is essential to how Adam and Eve are understood as individuals in the text.

Eve’s act of choice is also her final attempt to prove her individuality, the most visceral yet decisive way she can create a distinction between herself and Adam as her progenitor. By eating the fruit, Eve realizes her decision renders her “more equal, and perhaps, / A thing not undesireable, somtime / Superior: for inferior who is free” (PL 9.823-825)? Eve’s quest for freedom becomes the story of her self-development, from a creature formed from Adam to a wholly autonomous person. Eve reflects on how her choice denies Adam’s nasculine dominance, pushing back against the implications of the formation narrative:

Was I to have never parted from thy side? As good have grown there still a liveless Rib. Being as I am, why didst not thou the Head Command me absolutely not to go. (PL. 9.1153-1156)

Similar to how Sin chastises Satan, Eve taunts Adam, mocking him when saying that he as her superior is equally as responsible for her fall. Eve’s expression of anger toward Adam shows that choice, in addition to helping to free the submissive female, also helps her to recognize the inequality of her relationship. By drawing on the language of her submission, Eve indicates her retrospective understanding of how her formation in Adam had made her compliant.

To free themselves from the restrictive consequences of a male dominated formation narrative, Sin and Eve first achieve their physical separation and subsequently use choice to fortify their individuality. Eve and Sin prove themselves as apt decision makers once given the opportunity to choose freely. Although both women always possess the capacity to make difficult choices, it is their physical separation from their male progenitors which allows both women to finally act. Paradise Lost makes clear that implicit hierarchies of being are baseless - not dependent on rank at creation but upon the dynamics of self-development. In a gendered formation story, it is therefore paramount for female characters, who begin life at a significant disadvantage to their male counterparts, to express their autonomy though free action.

Works Cited

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Edited by Barbara Kiefer Lewalski, Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Milton, John, and Roy Flannagan. “Areopagitica,” from The Riverside Milton. Houghton Mifflin, 1998. pp. 978-1024.

0 notes

Photo

Long Lived the King: The Extent of Chivalry in Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur

The chivalric code is a fundamental feature of Malory’s “The Deth of Arthur,” characterizing a system of conduct which unifies all knights in Arthurian society under the leadership of the King. The code serves the equally important purpose of holding knights accountable for their actions as well as prescribes how they should react in situations which put their honour, or that of their brethren, into question. Yet, the most direct challenge to chivalric code and the society on which it rests comes from within the inner circle of the Round Table itself. Sir Launcelot’s elicit sexual relationship to Queen Guinevere is a blatant misgiving on the part of Arthur’s most celebrated knight, causing an internal crisis in Arthur’s court for which the laws of chivalry provide no immediate solution. Although Launcelot strains his relationship to Arthur, the adverse response of Sir Gawain and other knights of the Round Table to Launcelot’s indiscretion only further aggravates the situation – ultimately resulting in fracturing of Arthur’s kingdom. Launcelot’s ability to employ discretion, even when it means his defiance of the chivalric code, contrasts Sir Gawain’s rigid obedience to his feudal obligations and together reveal the limitations of a society governed by the laws of honour.