Text

Brief on "Psychedelic Science, Contemplative Practices, and Indigenous and Other Traditional Knowledge Systems"

Paper

Urrutia, Julian, Brian T Anderson, Sean J Belouin, Ann Berger, Roland R Griffiths, Charles S Grob, Jack E Henningfield, et al. “Psychedelic Science, Contemplative Practices, and Indigenous and Other Traditional Knowledge Systems: Towards Integrative Community-Based Approaches in Global Health.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 55, no. 5 (October 20, 2023): 523–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2023.2258367.

Abstract

As individuals and communities around the world confront mounting physical, psychological, and social threats, three complimentary mind-body-spirit pathways toward health, wellbeing, and human flourishing remain underappreciated within conventional practice among the biomedical, public health, and policy communities. This paper reviews literature on psychedelic science, contemplative practices, and Indigenous and other traditional knowledge systems to make the case that combining them in integrative models of care delivered through community-based approaches backed by strong and accountable health systems could prove transformative for global health. Both contemplative practices and certain psychedelic substances reliably induce self-transcendent experiences that can generate positive effects on health, well-being, and prosocial behavior, and combining them appears to have synergistic effects. Traditional knowledge systems can be rich sources of ethnobotanical expertise and repertoires of time-tested practices. A decolonized agenda for psychedelic research and practice involves engaging with the stewards of such traditional knowledges in collaborative ways to codevelop evidence-based models of integrative care accessible to the members of these very same communities. Going forward, health systems could consider Indigenous and other traditional healers or spiritual guides as stakeholders in the design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based approaches for safely scaling up access to effective psychedelic treatments.

Annotations

“We propose the development of community-based models of integrative care that draw from three complimentary approaches to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual care, which are largely underappreciated within conventional thinking and practice among the biomedica” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 523)

“and public health communities: psychedelic science, contemplative practices, and Indigenous and other traditional knowledge systems.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 524)

“Interestingly, many individuals who report challenging experiences nevertheless report subsequent improvements in well-being, and research suggests that most unpleasant reactions tend to be transient and do not diminish the therapeutic benefit (Carbonaro et al. 2016; Schlag et al. 2022).” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 527)

“Shared communal practices embodied in these self-transcendent modalities, in which relational experiences of perceived togetherness and shared humanity arise, can be effective at fostering beneficial outcomes (Joyce et al. 2018; Kettner et al. 2021; Piff et al. 2015). Research should evaluate whether embedding such practices in communitybased group settings could enhance or extend their efficacy, a topic discussed later.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 528)

“Proficiency with meditation appears to have powerful synergistic effects when combined with psychedelics such as psilocybin and ketamine, an effect observed both in individual settings and group retreats (Grabski et al. 2022; Griffiths et al. 2008; Lukasz et al. 2019)” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 528)

“However, Indigenous and other traditional knowledge systems generally do not draw such sharp separations between body, mind, and spirit, and individuals are less commonly addressed without also considering their social context (Fotiou 2020; Labate and Cavnar 2014; Marcus 2022; Winkelman 2010). Many Indigenous and other traditional knowledge systems see ailments as stemming from imbalances in the way we relate to ourselves, to our communities, to the environment, and to spirits that inhabit unseen worlds.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 529)

“The rituals in which these substances are embedded tend to be holistic practices addressing the preparation for, participation in, and integration of psychedelic experiences through diets, prayer, singing, dancing, and social congregation.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 529)

“Such points of convergence are opportunities for codeveloping evidence-based, complimentary care models that may transform health systems’ ability to improve health outcomes and equity at population levels.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 529)

“A decolonized agenda for psychedelic research and practice involves engaging with the stewards of such traditional knowledges in collaborative and equitable ways to codevelop evidence-based models of integrative care accessible to the members of these very same communities.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 529)

“Traditional healers and spiritual leaders could also be regarded as key community partners by health systems, which should enhance their capacity to address population health needs through community-based care models that rely on task sharing (see Table 1).” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 529)

“Indigenous peoples have historically and contemporarily been excluded from deliberations and decisionmaking related to psychedelic research, praxis, and policy (Celidwen et al. 2023).” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 530)

“While more research is needed, these findings provide preliminary support for an approach that involves coordination between community organizations or faith-based institutions and healthcare systems to provide group-based care (Castillo et al. 2019).” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 530)

“The current standards for psychedelicassisted psychotherapy involve one to two mentalhealth professionals for each individual seeking care, a ratio that is unfeasible in most settings but especially in LMICs where the median number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population is 0.1 (compared to 9.2 in HICs) (WHO 2021). One strategy for addressing workforce shortages is applications of group therapy, which has the potential to reduce overall costs and ease the projected shortage of qualified providers (Marseille 2023)” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 531)

“Training nonspecialist workers to deliver communitybased interventions is a cost-effective strategy for increasing the provision and quality of mental health services and improving patient outcomes (Caulfield et al. 2019)” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 531)

“A critical question is whether psychedelic therapies for serious mental and general medical conditions can be delivered safely and effectively through communitybased approaches by non-specialized providers.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 531)

“Health systems should regard such individuals as key stakeholders in the design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based approaches that rely on task sharing for safely scaling up access to effective psychedelic treatments.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 531)

“What is needed are guidelines developed through public-private partnerships that engage a broad spectrum of global experts and stakeholders from the science community, practitioners, Indigenous communities, faith-based communities, and advocacy groups representing numerous other communities (Belouin et al. 2022).” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 531)

“there is a need for translational research examining community-based practices.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 532)

“As such, global public health considerations regarding integrative care models aimed at improving health and human flourishing (vis-a-vis psychedelics, contemplative practices, and Indigenous and other traditional knowledge systems) should include rigorous debate and action that include an agreed upon public health research agenda, followed by learning and applied interventions through evidence-based policy making.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 532)

“In anticipation of rescheduling psychedelic medicines, health systems research on service delivery outputs, such as equitable access, availability, acceptability, quality, and efficiency to improve coverage, should aim to enhance health outcomes across all levels of the healthcare system, but particularly at the community level” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 532)

“A community-based care model coordinated with the healthcare system must be flexible enough to be adapted to country contexts and consistent with regulatory frameworks.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 532)

“The societal implications from equitable exchanges between traditional knowledge systems and biomedical evidence-driven research may prove profound for governments, communities, and individuals, which would foster health, wellbeing and human flourishing in the face of the calamities humanity must navigate.” (Urrutia et al., 2023, p. 533)

Personal Memo

Surely, the current individual-based psychedelic-assisted therapy model is expensive for ordinary people (the price ranges from $800 to $2500), making them less accessible to psychedelics. Moreover, the process excludes communities and other integration processes after psychedelics. This paper suggests an alternative model to address those issues. It is one of the few that truly reflects this integrative direction I am passionate about pursuing.

Well written and a bold direction suggested. But a more specific and practical direction is needed from now on. For example, this paper suggests that health systems should regard traditional healers as key stakeholders in the design and implementation. However, the region where traditional healers are active is quite confined, so how would we deal with places where there are no traditional healers? Task sharing with non-specialized workers was suggested as an alternative, but it seems vague and not practical.

0 notes

Text

Brief on "Psychedelic-Assisted Group Therapy: A Systematic Review"

Paper

Trope, Alexander, Brian T. Anderson, Andrew R. Hooker, Giancarlo Glick, Christopher Stauffer, and Joshua D. Woolley. “Psychedelic-Assisted Group Therapy: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 51, no. 2 (March 15, 2019): 174–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1593559.

Abstract

Contemporary research with classic psychedelic drugs (e.g., lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin) is indebted to the twentieth-century researchers and clinicians who generated valuable clinical knowledge of these substances through experimentation. Several recent reviews that highlight the contributions of this early literature have focused on psychedelic-assisted individual psychotherapy modalities. None have attempted to systematically identify and compile experimental studies of psychedelic-assisted group therapy. In therapeutic settings, psychedelics were often used to enhance group therapy for a variety of populations and clinical indications. We report on the results of a systematic review of the published literature in English and Spanish on psychedelic-assisted group therapies. Publications are characterized by their clinical approach, experimental method, and clinical outcomes. Given the renewed interest in the clinical use of psychedelic medicines, this review aims to stimulate hypotheses to be tested in future research on psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, group process, and interpersonal functioning.

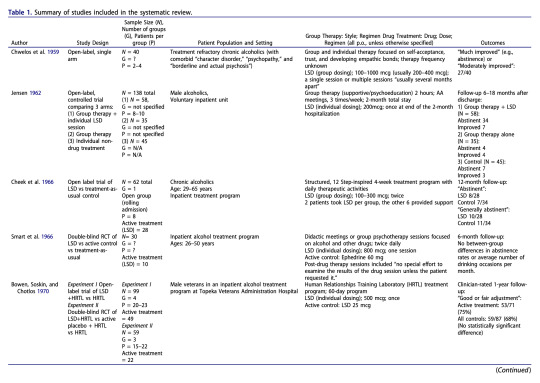

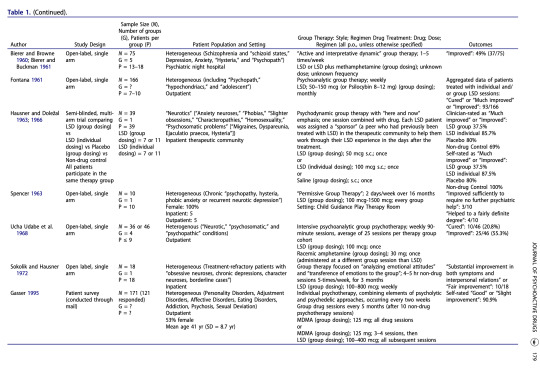

Table

Annotations

“Group psychedelic use in nonclinical contexts (e.g., ayahuasca or peyote rituals) is beyond the scope of this review” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 174)

“As psychedelic medicines enter pivotal trials in the United States and Europe, the prospect of postapproval clinical innovation with different administration modalities, including group therapy, arises.” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 175)

“12 studies met inclusion criteria, which required that the article contain some description of group methods, demographic and diagnostic information, and quantified outcome data.” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 175)

“It is notable, however, that the two positive studies —as well as the single uncontrolled study for alcoholism (Chwelos et al. 1959)—used either a 12-Step model or group therapy specifically adapted for psychedelic administration, while the studies with null findings did not use these elements.” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 185)

“The AmericanGroup Psychotherapy Association has made available evi-dence-based clinical practice guidelines and validated mea-sures to assess interpersonal functioning and groupcohesion (Bernard et al. 2008; Krogel et al. 2013; Strauss,Burlingame, and Bormann 2008)” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 185)

“The range of clinical approaches used in these reviewed studies illustrates the complexity involved in designing future trials of psychedelic-assisted group therapy. The optimal number of group members, drug dose, sequencing and number of group sessions, and type of group therapy are among the variables to consider. As opposed to the group administration of psychedelics that was common in early research, researchers today will likely, at least at first, use groups solely for the preparation and integration of individual psychedelic administration sessions.” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 185)

“Because preparatory and integration sessions entail the majority of total therapy hours a patient receives in modern protocols, delivering these sessions in a group format may improve the cost-benefit and time efficiency of research and clinical operations (Villapiano 1998).” (Trope et al., 2019, p. 185)

Personal Memo

Although I have heard that 1960s research was quite wild, it is still shocking to read the specific descriptive lines directly: “Individual drug sessions took place in a single room with patients physically restrained to a bed with a Posey belt during the duration of peak drug effect” (Smart et al., 1966). “Pilot study of 75 patients receiving LSD or LSD plus methamphetamine in a group setting at a psychiatric night hospital that served as a partial hospitalization program” (Bierer and Browne, 1960).

In my opinion, the efficacy of psychedelic group therapy lies in the comparison to individual psychedelic therapy, but there were no studies addressing this comparison in the reviewed paper. Moreover, as the authors stated, there can be various ways group therapies can be conducted (“The range of clinical approaches used in these reviewed studies illustrates the complexity involved in designing future trials of psychedelic-assisted group therapy”). The optimal design for psychedelic group therapy would be definitely challenging but interesting.

There have been some psychedelic group therapy sessions, including ayahuasca experiments conducted since 2018, which are, of course, excluded in this paper since it was published in 2018. A new review paper summarizing such recent research would be welcomed.

0 notes

Text

Brief on "Set, Setting, and Clinical Trials: Colonial Technologies and Psychedelics: Experiment"

Paper

Dumit, Joseph, and Emilia Sanabria. “Set, Setting, and Clinical Trials: Colonial Technologies and Psychedelics: Experiment.” In The Palgrave Handbook of the Anthropology of Technology, edited by Maja Hojer Bruun, Ayo Wahlberg, Rachel Douglas-Jones, Cathrine Hasse, Klaus Hoeyer, Dorthe Brogård Kristensen, and Brit Ross Winthereik, 291–308. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7084-8_15.

Annotations

“EBM stems from at least three facets of the rise of statistical medicine in the mid-twentieth century. The first relates to the need to create a new standard of proof for the statistical causation of emphysema through smoking.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 293)

“The second concerns the creation of experimental statistical medicine through RCTs.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 293)

“Historian Harry Marks (2000) notes that in the case of acute diseases and treatments like antibiotics, for which endpoints and improvement were easier to define, trials worked quite well.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 293)

“For chronic diseases, there were a host of difficulties: ‘the strategy of collecting more and more data in the course of a study ran the risk of producing more, not less, controversy’ (Marks 2000, p. 161).” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 293)

“The third aspect of statistical health involved large-scale prospective clinical studies.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 293)

“One way in which medical anthropology critiques this growing prevalence of RCTs is through attacking the reductiveness of its magic bullet approach, or what Richard Degrandpre (2006) calls ‘pharmacologicalism’; this is founded on the supposition that it is the drug’s chemical structure that determines the drug’s action in the body and not the environment of the treatment or the experience of the patient (so-called nonpharmacological factors).” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 294)

“In other words, even though these clinical trials give unprecedented attention to the setting of the pharmacological intervention, our sense is that they still operate within an underlying pharmacological ideology in which the new magic bullet is the molecule in a particular container.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 295)

“Here we focus on the fact that the marketoriented RCT is often controlled precisely in order to show that the drug is effective through comparison with those patients not receiving the drug, those in the placebo arm of the trial” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 296)

“From the perspective of drug developers, when trials fail, it is not that the drug does not work but that ‘noise’ has crept into the process. (Lakoff 2007, p. 65)” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 296)

“The Johns Hopkins psychedelic clinical trials on smoking cessation and existential anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer were landmark interventions, because they showed an incredible size of effect compared with all previous treatments, and they did so thanks to the extensive preparation given to patients, psychotherapy for mindset, and the meticulous production of a caring setting (Johnson et al. 2017).” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 297)

“Regular ayahuasca rituals now take place in over forty countries including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Israel, India, Japan, Russia, and twenty-two European countries (Labate and Loures de Assis 2017).” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 299)

“What interests us in these specific ritual formations, in the context of the argument we are making here about container technologies, is the way they actively refuse to know what the problem is ahead of the encounter with the plant spirit.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 299)

“It is it [ayahuasca] that is going to say what needs to be done, and I will execute that’ (de Rose 2006, our translation). Their choice of words is particularly interesting, as they describe ayahuasca as being the intelligent agent in the encounter and themselves as the tool or technology.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 300)

“It is not straightforwardly attributable to the molecular properties of ayahuasca, nor to Larissa’s intention, nor to that of any of the facilitators holding space for her process.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 301)

“While in clinical trials the intervention needs to be calibrated across all study subjects to enable comparison, and the subjects calibrated as equally suffering, in these circles it is often assumed that no two situations are ever the same and that nothing about a person’s process can be known from the outside” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 301)

“In both Larissa’s story and in de Rose’s account, the encounter with ayahuasca is experienced as neither heroic technology nor magic bullet; rather, it is the source of understanding the situation, the healer or guide for the individual and the collective.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 301)

“Yagé is not a hallucinogen and is not a psychedelic plant. Yagé is a plant that has a living spirit and teaches us how to live in peace and harmony with Mother Earth. (UMIYAC 2019)” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 302)

“They are first and foremost concerned with providing a space for a process to unfold, where what unfolds is not reducible or attributable to the isolated actions or intentions of either healer or client.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 304)

“The weapons that enforce it, the knowledge institutions that legitimize it, the financial institutions that operationalize it, are also technologies.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 305)

“If set and setting are ever to have any real-world value, then they would have to include not just structural determinants of health and inequality, but spirits, community, time, the forest and equitable forms of inhabiting the world, for humans and more-than-humans.” (Dumit and Sanabria, 2022, p. 305)

Personal Memo

I agree with the author’s critiques of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) model based on Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), particularly concerning psychedelics. As a counterexample to EBM and RCTs, the author provides the example of ayahuasca, highlighting its role in understanding the individual and collective contexts of the healer or guide. I found this perspective compelling.

It was particularly interesting to note how indigenous people describe ayahuasca as an intelligent agent in the encounter, contrasting sharply with the materialistic perspective of Westerners.

However, I believe the author’s use of the term ‘colonial technologies’ is overly aggressive in interpreting current research trends. While it is accurate to some extent, it should not be viewed as all-encompassing. The acceptance of EBM and RCTs has not primarily been to establish a colony or build a pharmaceutical empire but because they have been effective until the emergence of psychedelics. Psychedelics, with their unique characteristics of longitudinal effects and context amplification, seem to challenge the effectiveness of EBM and RCTs.

It is evident that an alternative research approach to EBM and RCTs is needed, but the question remains: how? Research still requires proof and a reference point. What is the best method to incorporate the example of ayahuasca into practical research principles? Perhaps more context should be included, respecting the uniqueness of each situation and acknowledging that absolute control is impossible. However, the solution is not yet clear, and this gap needs to be investigated further.

0 notes

Text

Brief on "Acute subjective effects in LSD- and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy"

Paper

Schmid, Yasmin, Peter Gasser, Peter Oehen, and Matthias E Liechti. “Acute Subjective Effects in LSD- and MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy.” Journal of Psychopharmacology 35, no. 4 (April 1, 2021): 362–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120959604.

Abstract

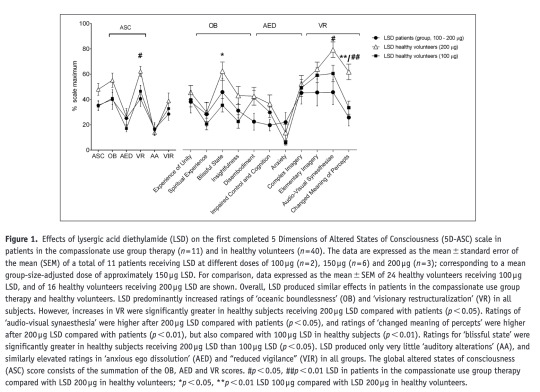

Background:Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) were used in psychotherapy in the 1960s–1980s, and are currently being re-investigated as treatments for several psychiatric disorders. In Switzerland, limited medical use of these substances is possible in patients not responding to other treatments (compassionate use).Methods:This study aimed to describe patient characteristics, treatment indications and acute alterations of mind in patients receiving LSD (100–200 µg) and/or MDMA (100–175 mg) within the Swiss compassionate use programme from 2014–2018. Acute effects were assessed using the 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness scale and the Mystical Experience Questionnaire, and compared with those in healthy volunteers administered with LSD or MDMA and patients treated alone with LSD in clinical trials.Results:Eighteen patients (including 12 women and six men, aged 29–77 years) were treated in group settings. Indications mostly included posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Generally, a drug-assisted session was conducted every 3.5 months after 3–10 psychotherapy sessions. LSD induced pronounced alterations of consciousness on the 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness scale, and mystical-type experiences with increases in all scales on the Mystical Experience Questionnaire. Effects were largely comparable between patients in the compassionate use programme and patients or healthy subjects treated alone in a research setting.Conclusion:LSD and MDMA are currently used medically in Switzerland mainly in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in group settings, producing similar acute responses as in research subjects. The data may serve as a basis for further controlled studies of substance-assisted psychotherapy.

Personal Annotations

“The present prospectively designed study assessed the patient characteristics, diagnoses, and acute subjective responses to LSD and/ or MDMA (as assessed immediately after the treatment session) from December 2014–March 2018 in patients treated in compassionate use group therapy in Switzerland.” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 2)

“Higher doses of LSD did not produce greater effects than lower doses in the compassionate use group (Supplementary Material Figure S2).” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 6)

“There was no difference in the proportion of complete mystical experiences between groups (χ2 (3,4) = 0.96, not significant (NS)).” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 6)

“MDMA produced greater effects in patients in the compassionate use group therapy compared with healthy volunteers as evidenced by a greater MEQ30 total score (t35 = 4.1, p < 0.001).” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 8)

“However, total mystical experiences did neither occur in patients in the compassionate use group therapy nor in healthy subjects.” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 8)

“MDMA did not produce a statistically significant increase in experience of unity in the compassionate use group therapy, whereas this has repeatedly been demonstrated in healthy subjects (Hysek et al., 2012c; Schmid et al., 2014; Studerus et al., 2010).” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

“LSD produced significant elevations in the experience of unity in patients treated in the group setting” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

“In the compassionate use group, MDMA produced only small, though significant, increases on the MEQ, and contrary to those observed with LSD, most ratings were higher than those of healthy subjects” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

“Nonetheless, no total mystical experiences were observed in both groups with MDMA, in line with previous reports (Liechti et al., 2017; Lyvers and Meester, 2012)” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

“However, patients in the compassionate use programme also displayed greater ratings of spiritual experience and insightfulness on the 5D-ASC scale than healthy subjects after MDMA, indicating that the group setting may be more appropriate to induce at least some aspects of mystical-type experiences.” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

“Overall, it is unclear whether different dosages not only affect the acute but also the therapeutic effects.” (Schmid et al., 2021, p. 10)

Personal Memo

Although there were no total mystical experiences observed in both groups with MDMA and LSD, at least, the psychedelic group therapy was comparably not worse than individual settings.

In the MDMA trial, the group settings were more effective in all aspects from MEQ 30: mystical, positive mood, transcendence of time/space, ineffability.

0 notes

Text

Brief on "Community-based psychedelic integration and social efficacy"

Paper

Gezon, Lisa L. “Community-Based Psychedelic Integration and Social Efficacy: An Ethnographic Study in the Southeastern United States,” May 27, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2024.00381.

Abstract

Background and aims This qualitative ethnographic study of a psychedelic integration group in the Southeastern United States contributes to an understanding of the role of supportive communities in processing psychedelic experiences. This article proposes the concept of ‘social efficacy’ to capture the importance of social relationships to the efficacy of psychedelics. Social efficacy refers to a source of efficacy that includes not just the immediate social environment in which psychedelics are experienced and processed, but also the broad range of social relationships and political economic and historical contexts that frame their use. Methods This year-long ethnographic research project took place with a psychedelic integration group in an urban center in the Southeastern United States. It was based on observation, interviews, and a focus group. Results Overall, the participants in the integration group see the group as critical to their ability to effectively process their psychedelic experiences. The group is important as a supportive community of like-minded people that facilitates enduring cognitive and affective transformation. Conclusions Community-based non-therapeutic integration groups can play a vital role in the positive integration of psychedelic experiences, improving mental health and quality of life for users. The important role of community-based groups has significance for both the legalization and the medicalization of psychedelics. It highlights the need for safe and legal spaces in which people can talk about their psychedelic experiences and for medical models of efficacy that include social, relational elements.

Annotations

“‘social efficacy’” (Gezon, 2024, p. 1)

“source of efficacy that includes not just the immediate social environment in which psychedelics are experienced and processed, but also the broad range of social relationships and political economic and historical contexts that frame their use.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 1)

“Community-based non-therapeutic integration groups can play a vital role in the positive integration of psychedelic experiences, improving mental health and quality of life for users.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 1)

“a semi-public discussion group that provides a setting for sharing and making sense of psychedelic experiences and for exploring curiosity about these substances.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“‘integration groups,’ or ‘integration circles,’” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“reintegration into society with a new phenomenological, affective, and cognitive subject positions (Turner, 1969).” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“describes how we can bring insights from a psychedelic experience into our lives at large” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“Considering psychotherapeutic models, Brennan and Belser (2022) contrast what they refer to as a” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“basic support model, which includes minimal therapist intervention into integration processes, with models that include therapeutic approaches in addition to the immediate safe administration of substances.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“Santo Diame” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“policies and integration practices that recognize the role of indigenous and other communities in the effectiveness of psychedelics.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“mindsets are not static ‘things’ people carry with them into psychedelic experiences.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“Rather, they are dynamic and fluid states in interaction with relational processes through which worldviews shift or become actively reinforced.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 2)

“At the beginning of the meeting, the group chooses three words or phrases to discuss as they relate to psychedelic experiences.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 3)

“he chose the model because he noticed that smaller groups tended to facilitate deeper conversations as well as greater intimacy and connection between members.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 3)

“For one, the group meets once per week, which is often enough to build bonds.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 3)

“After that group session, one participant said that her partner shared with her that “this group may be the most impactful thing he will ever be part of in his life”” (Gezon, 2024, p. 4)

“she told her girlfriend that the group felt like “all the good stuff of what we love about the church without any of the yucky stuff.”” (Gezon, 2024, p. 5)

“Dumit and Sanabria (2022) challenge the ability of randomized controlled trials (RCT) to produce standardized, universal efficacy, considering its focus on decontextualized individuals as well as its exclusionary, colonial practices of knowledge production and financial gain.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“A concern of Noorani, Bedi, and Muthukumaraswamy (2023) is that “the proliferation of psychedelic [randomized control tests] that are currently underway is that they will achieve little for understanding the complex chemosocial properties of psychedelic interventions”” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“As critics of the RCT model, Dumit and Sanabria (2022) call out the ‘magic bullet’ ideology that places the contextfree pharmaceutical agent as a simple determining factor of efficacy, ignoring set, setting, and the potency of the placebo effect.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“Hendy (2022) traces discussions of chemical versus self-efficacy, the latter of which is not a simple biochemical process, but rather emanates from an interaction between the chemical and the psychological self, often mediated by therapeutic encounters, with the implication that the chemical will act differently on different individuals based on their psychological makeup.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“On the other hand, consideration of social efficacy also requires attention to social relationships outside of the immediate psychedelic event, including friends, family, mental health and other healthcare professionals, and co-workers, for example, who may or may not recognize taking psychedelics as legitimate.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“This ethnographic research with integration groups has underscored the importance of extra-therapeutic social relationships as critical for understanding the efficacy of psychedelics” (Gezon, 2024, p. 6)

“A consideration of only the chemical, or only the chemical plus an individualistic psychological process as mediated by a therapist, misses a critical component of psychedelics’ efficacy.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 7)

“The concept of social efficacy was introduced here to underscore the necessity of considering extra/non-therapeutic social contexts when analyzing mechanisms for the effectiveness of psychedelics.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 7)

“sense of connectedness to others is a common factor in many forms of social wellbeing (Waldinger & Schulz, 2023), which helps explain why the benefits of psychedelics are enhanced by their integration into nontherapeutic everyday life.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 7)

“To compartmentalize the process of integration as existing merely within interpersonal encounters immediately following the psychedelic experience (often transactional mental health therapy) is to ignore the way that integration processes spread in barely perceptible ways into domains of everyday encounters.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 7)

“Earleywine et al. (2022) found that the majority of respondents described integration as “an ongoing process that never ends” (p. 7).” (Gezon, 2024, p. 7)

“psychedelic rituals reinforce social group membership and shape transformed ways of understanding (Dupuis, 2022).” (Gezon, 2024, p. 8)

“Tempone-Wiltshire and Matthews (2023) discussed the possibilities of psychedelics to challenge hegemonic worldviews by inviting perceptions that “challenge the paradigmatic assumptions of industrial society by provoking alternative epistemologies and metaphysics”” (Gezon, 2024, p. 8)

“Studies have shown that effective harm reduction occurs at the grassroots level (Hardon et al., 2020), based at least in part on community- and peer-based and sometimes online (Barratt, Allen, & Lenton, 2014) groups who generate norms and practices supporting self-regulation, prevention, and intervention in case of harm.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 9)

“. Second, and perhaps more poignantly, the pharmacological approach to harm reduction ignores social efficacy” (Gezon, 2024, p. 9)

“To change this, George et al. (2019) present practical recommendations, such as meaningful (not tokenized) collaborations between researchers and communities.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 9)

“In a global online survey of ayahuasca users, Cowley-Court et al. (2023, p. 217) found the role of community to be just as if not more important than psychotherapy.” (Gezon, 2024, p. 9)

Personal Memo

There are multi facetes of ‘group therapy’

Concurrent vs Post Sharing : There is a difference between taking psychedelic drugs with a group (i.e., ayahuasca) or taking them individually and then gathering later to talk about it (this paper). However, there is no distinguish between them.

Therapeutic Group vs Community Group : In most papers under experimental settings, ‘group’ meant a therapeutic group under traditional clinical environment. However, this paper describe group as a more community integrated one.

and more facets

is done : Official vs Underground

therapist’s role : none vs minimal (i.e., sitter) vs active (i.e., shaman)

context : party, religious, clinical, etc

There are many good references.

0 notes

Text

Brief on Gasser, “Psychedelic Group Therapy.”

doi

10.1007/7854_2021_268

Abstract

Gatherings in groups are a ubiquitous phenomenon throughout human history. This is true for everyday social tasks as well as for healing and spiritual purposes. In psychotherapy, group treatment started soon after developing psychoanalytic treatment procedures. For psychedelic therapy however, individual treatment guided by one or sometimes even two therapists is the most common and widespread treatment model for clinical research and therapy thus far. Since the foundation of the Swiss Medical Society for Psycholytic Therapy (Schweizerische Ärztegesellschaft für psycholytische Therapie, SÄPT) in 1985 in Switzerland, we however had the opportunity to conduct psychedelic group treatment in specific settings, which the following article describes.

Annotation

“Books like “The Secret Chief” by M. J. Stolaroff (1997) and “Therapy with Substance” by F. Meckel Fischer (2015) show the existence and the structure of such underground group meetings.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 3)

“Yalom (2005) dedicated a whole novel “The Schopenhauer Cure” to the long lasting ambivalence of the protagonist to participate in a group therapy.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 3)

“How fortunate that there was a sharing round. To learn what and how the others in the group experienced and to listen to the feedback they gave each other was extremely valuable. I would not have wanted to miss their mutual sharing of experiences, nor my own one. I am proud and grateful that I participated in this workshop” (Gasser, 2022, p. 4)

“I felt a floating calmness within myself . . . and a connectedness with every single person, and together as a whole in that room.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 5)

“These deep encounters have to be brought back and translated into everyday life, like Christian Scharfetter stated (Scharfetter 1997): “I am not so much interested in what kind of spiritual experiences people have, I am more interested in what they have done with them”.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 5)

“I discourage too much contact during the acute effect of the substance for the first 5 h approximately. This allows an undisturbed individual process.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 5)

“they applied a group setting approach immediately in 1988 when they received their special permission for treatments with MDMA or LSD (Jungaberle and Verres 2008).” (Gasser, 2022, p. 5)

“On average the patients underwent seven sessions with MDMA and/or LSD within 3 years and during this time 70 individual talking psychotherapy sessions were held. The 3-year training that SÄPT offered for therapists from 1989 until 1992 with 12 weekend workshops was all done in a group setting.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 6)

“During an underground group therapy workshop in Berlin in 2009, two participants died and two others were several weeks in hospital treatment due to the therapist combining two substances (MDMA and Methcathinone) and applying a 10 times overdosage of MDMA (information from the therapist involved, during a personal conversation). In Handeloh, Germany, in 2015, a massive overdosage of an unknown new substance happened during an underground group gathering of health practitioners. In a large-scale ambulance operation 27 therapists had to be treated in emergency at the location where the workshop happened.” (Gasser, 2022, p. 6)

Peresonal Memo

It is surprising that the psychedelic group therapy was conducted legally in the 80s and 90s in Switzerland. However, the papers were written in Swiss languages, so accessibility might have been limited.

Should read Schmid et al. (2020)’s paper. They compared group therapy with individual therapy. I haven't read the paper yet, but one unfortunate aspect is that the results of group therapy are combined, whereas individual therapy is divided by dosage.

SAPT is interesting.

What could be a better method for psychedelic research than using double-blind, RCS, and Questionnaire? Although fMRI is used, it also affects the setting.

Group Therapy works well despite concerns and is even cost effective.

0 notes

Text

Lecture Summary Notes on Andrew Gallimore’s Brain Master Course

This document is a summary of key points from Andrew Gallimore's Brain Master Course, compiled for personal study. The total length of the course is approximately 12 hours. This summary can help you understand the relationship between psychedelics and the brain in a brief time frame. Please be aware that there may be unintentional errors or omissions.

You can access the complete course content via the link provided. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLbqdD4EM-aEfmLvbWu8GQDhUII236MZf-

0 notes

Text

Summary :

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris: The Science of Psychedelics for Mental Health (1/2)

This summarizes the podcast interview with Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris on the Huberman Lab Podcast.

Dr. Carhart-Harris is a leading researcher in the field. Let's explore the therapeutic potential of these substances, how they work in the brain, and their applications in treating various mental health conditions. Note that this summary just covers half of the podcast.

The word ‘psychedelic’

Huberman inquired about the definition of psychedelics and the origin of the word 'psychedelic'. Dr. Carhart-Harris explained that it comes from Humphry Osmond, who was dissatisfied with the term “psychotomimetics” for psychedelic drugs because their effects were far beyond those implied by psychomimetics. In collaboration with Aldous Huxley, Osmond coined the term ‘psychedelic’. ‘Psyche’ means human mind and ‘delic’ means make clear. Carhart-Harris believes it’s a very accurate and useful term because these substances reveal aspects of the mind, whether heavenly or hellish.

Psychedelics & revealing the unconscious mind, psychotherapy

Next, Huberman delved into the power of psychedelics in revealing the mind, using an example related to the subconscious: blind people guessing the number of dots on a screen with accuracy far greater than chance would predict.

Dr. Carhart-Harris clarified that this example pertains to the subconscious, but psychedelics are more about the unconscious. When psychedelic drugs like LSD and psilocybin are used in psychotherapy, repressed material often emerges, which has therapeutic value. This process catalyzes the therapeutic experience with strong emotional release. He added that if only ketamine and MDMA were available, they might have captured the world’s attention just as psychedelics have.

Microdosing

Later, Huberman turned to the topic of microdosing and its guidelines. Dr. Carhart-Harris defined microdosing as taking a dose of a psychedelic that doesn’t induce a noticeable altered state. It typically involves taking the dose semi-regularly, for instance, one day on and one day off. For LSD, this is around 10 to 12 micrograms.

However, he added that microdosing lacks compelling evidence because it’s hard to study in lab conditions. Researchers need permission to give a microdose and follow it three times per week for certain number of months.

Balazs Szigeti, instructed people to do their own placebo control but microdosing didn’t compelingly beat placebo. I searched and this is the paper he mentioned.

Self-blinding citizen science to explore psychedelic microdosing

He also said that a study in NewZealand did the design right but hadn’t been published yet. When I searched, I found that the paper had been published and stated that microdosing is quite safe and produce acute behavioral and neural effects in healthy adults.

Microdosing Psychedelics: Current Evidence From Controlled Studies

Its findings were different from Balazs Szigeti’s.

Psilocybin vs Magic Mushroom Doses

Huberman then sought clarification on the calibration of psilocybin, specifically how much 25 mg of psilocybin translates to in terms of grams of mushrooms.

Dr. Carhart-Harris estimated that the percentage of psilocybin in mushrooms is around 1%. Therefore, 1g of mushrooms contains approximately 1mg of psilocybin. He expressed a desire for a proper study to be conducted on this.

Psychedelic therapy experience , what you think is leading to that incredible positive and pervasive change in mood, state and trait.

Huberman was curious about the psychedelic therapy experience and what leads to significant positive changes in mood, state, and trait.

Dr.Carhart-Harris highlighted that the therapeutic outcomes are strong and reliabe across independent teams and studies. There is converging evidence now, more than just impulse.

In a typical therapy sesion, there are usually two professionals present : one is mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, and the other is psychotherapist.

As the drug effect begins, the body feels a little strange and there’s initial anxiety. The mind’s eye starts to notice patterns, and the experience gets deeper.

The patient doses this with eyes closed, in a settled condition, which is different from a rave party.

There is a music, typically without lyrics that is spacious to begin with, and then builds and becomes atmospheric. There is a definitely synergy between psychedelic and music.

importantance of “letting go”

Moving forward, Huberman explored the importance of having a mindset of letting go.

Carhart-Harris described that letting go involves trust, readiness to surrender, and not resisting. It is a staple component of how different teams conduct psychedelic therapy, emphasizing the encouragement of a willingness to let go. It’s a significant predictor of the quality of the experience in psychedelic therapy and is almost like a mantra.

He attributes this concept to Bill Richards, who guided him during his visit to Johns Hopkins.

Dr. Carhart-Harris noted that without the willingness to let go, the experience can sometimes become nightmarish and very intense. He also mentioned that Ph.D. candidate Ari Brouwer categorized phases of experience in psychedelic therapy, and this is the paper he referred to.

Pivotal mental states - Ari Brouwer, Robin Lester Carhart-Harris, 2021 ORCID

Negative Emotions & Fear

Huberman asked about anxiety in the psychedelic experience : is it the sensation peoples are experiencing or about some prior event being called to mind.

Dr.Carhart-Harris explained that the initial struggle is more against the general drug effect than pinning it on sometihng specific. What the drug does is break down all of assureness. Although it doesn’t pose a fertility risk, patients often feel like they’re going to die or lose the minds.

Global Function Connectivity

Huberman discussed a picture showing significantly increased brain connectivity under the influence of psychedelics and asked for evidence on whether this enhanced connectivity persists after the psychedelic journey ends.

Dr. Carhart-Harris explained that during the trip, there is a well-replicated increase in global functional connectivity, often referred to as decreased modularity, where different brain regions communicate more extensively across typical boundaries. He noted that this effect is observed during the psychedelic experience and can also be seen the next day. In two independent depression cohorts, this increased connectivity was still observable three weeks later. This residual effect correlates with the improvement in depressive symptoms, highlighting the significance of enhanced brain connectivity in therapeutic outcomes .

He also mentioned that a new on DMT will be published soon, showing a similar effect.

Pharmacology

Huberman referred to a paper from UC Davis about developing non-hallucinogenic psychedelic drugs and asked Dr. Carhart-Harris for his opinion.

Dr. Carhart-Harris expressed skepticism, stating that while the system and patients might love it, he hasn’t seen compelling examples and doesn’t see the logic behind it.

He explained that direct serotonin 2A receptor agonism could be driving the therapeutic response, but you can get that with SSRIs like Lexapro, which are not psychedelic.

Long term

Huberman asked if the increased connectivity between brain areas observed while under the influence of psychedelics also persists after the effects wear off, and to what extent neuroplasticity, structural changes in neurons, and functional changes in neurons are responsible for this, and how long it lasts.

Dr. Carhart-Harris stated that they don’t have a definitive answer yet but have seen data indicating increased connectivity lasting up to three weeks. He noted a correlation between this increased connectivity and improved mental health outcomes in depression patients.

Anorexia

Huberman asked how the psilocybin therapy for anorexia is progressing, noting that anorexia is deadly and many patients tragically lose their lives.

Dr.Carhart harris agreed with the severity of the situation and mentioned that there has been an improvement in weight during long-term follow-ups with 19 patients, but these findings have not been published yet.

1 note

·

View note