kenneth | 20 | ethics stuff, politics stuff, literature/film stuff, some other stuff | public personal thought journal

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Do Facts Care About Your Feelings?

Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings (or, for short, FDCAYF).

We’ve all heard this sentiment echoed before. In Ben Shapiro’s PragerU episode of the same name, on his Twitter feed, from the mouths of the millions of conservatives and alt-righters who tune in to his podcasts - the right wing has essentially heralded it as the be all and end all of one-liners to ‘destroy libtard SJWs’. At first glance, it seems like an impenetrable argument: after all, if facts did care about one’s feelings, then they’d cease to be objective.

One thing I’ll credit Shapiro with is how effective this phrase is at conveying what he’s trying to say. It accomplishes multiple things at the same time.

It:

1. Labels his opposition as ‘emotional’,

2. Makes a statement about the nature of facts,

3. Establishes the possession of facts as incompatible with his opposition, and

4. Therefore implies that his opposition is blinded from the truth by feelings.

Hold up. Let’s take a look at Point 2 for a moment. It almost seems like FDCAYF is an epistemic claim; he’s discussing how facts work, and how we can get to know them. I thought it might be interesting to see just how much this one-liner holds up to philosophical inspection.

Spoiler: eh, not much.

How The Argument Works

First, let’s talk about what exactly Ben is saying here. He’s making an analysis of what facts are, and proposing a certain feature that all facts share (that feelings do not affect them). In order to figure out whether this is correct, we of course need to understand what a fact is.

Many people, including some academic philosophers, would roughly define a fact as ‘a proposition that is true’. What this means is that, for something to be a fact, it must be truth-apt (be a statement that can be true or false), and it must be true. The reason why the first criterion is important is because it discounts statements that simply cannot possibly be true or false, like instructions or exclamations. ‘Go do your homework’ cannot be a fact because it doesn’t propose anything; likewise with something like ‘oh my god’ or ‘blimey’. On the other hand, a statement that does propose something that can be true or false like ‘tigers have four legs’ can be facts, as long as they’re true. That last bit is why ‘tigers have four legs’ is a fact, but ‘the grand canyon is a species of tiger’ is not; the former is a true proposition, while the latter is a false one.

I would think that most supporters of Ben would agree with this idea of what facts are; I imagine most people would. But this poses a problem for FDCAYF. After all, there are some true propositions where feelings and perspectives do matter. The statement ‘Billy loves basketball’ proposes something that could either be true or false. Let’s also assume that Billy does, in fact, love basketball. The truth of this claim does depend on feelings - in this case, Billy’s. Going by this idea of what facts are, we have to accept that ‘subjective facts�� do exist, and that therefore there exist some facts that do ‘care about your feelings’. Many philosophers are comfortable with accepting this, but obviously a hardcore Ben Shapiro fan would want to defend the FDCAYF. Admittedly, this idea of ‘subjective facts’ is quite nitpicky when looking at the facts Ben Shapiro usually refers to when he raises FDCAYF; stats, scientific studies - objective facts. So for the sake of good faith, maybe we can raise a definition of facts that’s more charitable to Ben Shapiro: ‘facts are propositions that are objectively true.’ What we mean by objective here is mind-independent, with the truth of the statement not depending on any feelings. This way, the only ‘facts’ that we have to deal with are the ones that Ben Shapiro actually approaches. It also means that he by definition cannot be wrong about facts not caring about your feelings, which is basically shooting this entire analysis in the foot, but bear with me. In the next few sections, we’ll discuss how even this charitable idea of what Ben Shapiro means by ‘facts’ doesn’t really give us the full picture of how facts work.

(PS: it’s worth noting that someone who sees the world as something leaning towards Idealism would reject this new definition as incoherent altogether, since under Idealism there would technically be no such thing as a mind-independent, wholly objective fact. But that’s besides the point, so we’ll save Idealism for another future post.)

Fact Versus Ideology

So. Let’s pretend everything we said earlier didn’t matter. We assume that facts by definition don’t care about your feelings, and so accommodate what Ben Shapiro uses as ‘facts’. Here’s the irony, though: it’s precisely by accommodating what Ben Shapiro says in context that we see this idea of facts fall apart too. Let me explain why.

The running trend with Ben Shapiro is that he’d claim some fact, then he’d promote it as an objective reason to support some conservative stance. For the sake of example, we’re gonna talk about the topic he arguably most famously does this with: transgender rights. More specifically, when he talks about trans people, he would point to the fact that they’re ‘biologically male/female’ to justify not referring to them by their preferred pronouns. (case in point here and here). He would use some biological fact, like how a male-to-female trans person would still possess XY chromosomes, to say that the conservative stance towards trans people is factual, and therefore conclude that those who disagree are simply ‘being offended by facts’ and ‘factually wrong’.

Going back to our Shapiro-approved definition of facts, we can see that his claim on male-to-female trans people possessing XY chromosomes is indeed a fact. However, Ben is trying to push for something deeper than just stating a fact; he’s also making a call to action. The argument he’s forming here is that ‘trans women are biologically male’, ‘therefore trans women are men’, ‘therefore we ought not to call them women’. This is the part where it becomes real messy, because we realise we aren’t just dealing with facts in and of themselves, but rather their political relevance. And while the facts themselves could be independent of how one feels, the political values that one infers from them - as we will see - are not.

What makes the fact ‘male-to-female trans people possess XY chromosomes’ more politically relevant than, say, the fact ‘koalas have smooth brains’? It’s the context under which we perceive the political. In other words, It is what we deem as politically problematic or politically relevant that leads us to decide which facts matter. The fact that trans men possess XY chromosomes might be a matter of huge importance to a neoconservative like Ben Shapiro, who thinks that one’s identity is defined biologically, but that fact would be less politically relevant to a more progressive-minded person - at least in determining a trans person’s identity - because they think that identity is primarily defined socially. It simply goes back to one’s ideology, and one’s general worldview of how society operates. Another example would be how the fact that ‘there are 6 times more empty homes than homeless people’ would be a matter of huge relevance to a communist, or a left leaning liberal, but would at the very most be a matter of curious interest to a conservative, simply because their ideology already inherently constructs an ‘if you didn't earn it, you don’t deserve it’ mentality. A fascist would find the fact that ‘African Americans, despite forming 13% of the population, constitute 50% of the prison demographic’ to be extremely politically relevant, while a socialist democrat would not, seeing that as explained ideologically through systemic oppression and injustice in the judicial system. There are countless examples we can choose from, because there are countless ideologies that each enable and are enabled by the facts that they find important. This isn’t to say that all ideologies are the same and that the one we choose to lean towards is a matter of subjective taste; it simply means that we shouldn’t deceive ourselves into thinking there is a fact-based reason to subscribe to one, and that people of other ideologies are not beholden to facts. In actuality, political discourse isn’t about what the facts are, it’s about which facts are important and give motivation to act. Ben Shapiro may be right in claiming that ‘[certain] facts don’t care about your feelings’, but how we use these facts does care about our values and worldview.

Reason Versus Feeling

Our earlier paragraph discusses how he conflates possessing facts with possessing rational beliefs about what these facts mean, and we have gone through why this is problematic. But in making this assumption Ben actually commits to a more fundamental claim about rationality, and that is the drawing of a dichotomy between rational action and emotion. That is, he’s saying that one cannot be both emotional and rational. To be fair to him, this is not a very uncommon idea; think of the many times we’ve seen people say ‘stop being so emotional and use your head’. But that way of thinking, of ‘Reason versus Feeling’, might not be as clear and obvious as we think.

Let’s start with understanding what it means to be rational. I think it’s fairly uncontroversial to say that to be rational is to act in accordance with reason; that is, to do what one has more reason to do. The prospect of getting a free chocolate bar could give me a reason to steal from the convenience store, but the stronger motivations of not wanting to be arrested for theft and not wanting to do something morally wrong would give me more reason not to steal, making not stealing the rational decision for me (well, assuming a perfectly normal circumstance). So what exactly is a reason? Such an abstract concept might be hard to define. But looking at the previous three reasons we’ve raised, we can try to come up with some necessary features of a reason. For example, we know that a reason can’t exist in and of itself. There’s no such thing as simply ‘a reason’. It’s always ‘a reason to do x’, or ‘a reason to believe x’. Reasons are always predicated on some other action or thought. This brings us to our second, and more important, feature of reasons: they always exist to justify or motivate a certain action or thought. They inform us about our motivations in acting on/believing something, and it’s through weighing our many reasons for and against this that we decide what is reasonable and rational. This obviously means that reasons are extremely diverse, and is the reason why philosophers like to make different categories of reasons when analysing them: we’ve got object given reasons (reasons derived from certain features of the object in question), state given reasons (reasons derived from the current state we’re in), hedonic reasons (reasons that involve our own personal pleasure and happiness)… but the category of reasons we’re gonna talk about today is much, much simpler than all of that: what about emotional reasons?

When we get ‘emotional’, it usually doesn’t just happen randomly out of the blue. Something happens, or we’re in a certain state of mind that makes us react emotionally. Certain states of affairs gives us reasons to act emotionally, and then we evaluate whether or not said emotional reaction is a justified response. Granted, many times we end up acting emotionally and irrationally. But that doesn’t mean that every emotional reaction is not reasonable or rational. If Steve steals my lunch, it is reasonable for me to be annoyed and tell Steve off. It’s not reasonable for me to murder him in a ravenous fit of wrath, but that’s because I can evaluate that this emotional response in particular is not warranted. In fact, think about every time someone got mad and asked one of his friends ‘was I being unreasonable for acting that way?’, or every time a parent had to ask themselves whether they were too harsh in their reprimanding of their child. If emotional reasons didn’t exist, then these questions would be useless and meaningless, since every emotional reaction would be irrational. Arguably, the whole subreddit r/AmITheAsshole deals with the problems of sorting out emotional reasons and deciding whether or not the emotional reaction these reasons led to was reasonable. The assumption about the distinction between rationality and emotion that Ben Shapiro makes when he says ‘Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings’, then, while not one that is altogether uncommon, is not really all that sustainable, since our feelings and the way we act from them can be evaluated from a rational lens.

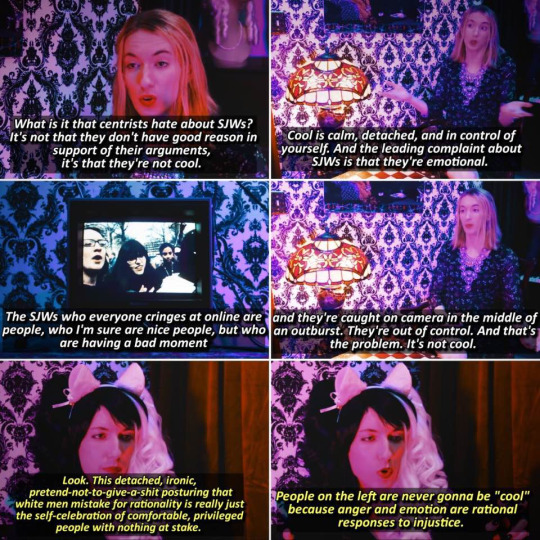

As a matter of fact, even our favourite neoconservative himself does this evaluation all the time. Every time Ben decides that a condescending retort is in order, every time he reacts with incredulity at another ‘outlandish leftist headline’, he is deeming this specific emotion as an appropriate reaction. But we usually don’t think of these things as acting emotionally. The point I’m trying to get at here is more than just Ben’s inconsistencies with his own dogma; it’s driving more towards how we treat emotion as a whole. We don’t usually think to call contempt and condescension emotional, despite the fact that they technically are. In fact, we’d celebrate them as ‘savage’ or ‘absolutely destroying’ someone (think ‘Ben Shapiro versus SJW cringe compilations’). On the other hand, we’re quick to see those who express outrage and anger and compassion as being emotional (and, to some, therefore irrational). Our discussions and analyses about what exactly constitutes reason and how emotion fits in are all well and good, but the discussion simply wouldn’t be complete unless we also talk about how we as a society approach this issue. And judging by the looks of it, we evaluate what is ‘emotionally irrational’ based not on what actually is emotional, but rather based on what emotions are socially approved. Delivering a ‘sick burn’ is perfectly reasonable and great, but getting ‘triggered’ is uncool and going off-the-hook. Worryingly, what we judge as being an irrational emotional response isn’t just about the scale and extent of the response, but the type of emotional response itself, and it’s not altogether clear why we should believe that some emotions are simply inherently more irrational than others. Natalie Wynn, better known as Contrapoints, puts it better than I think I ever could

Perhaps a more accurate, albeit less catchy, phrase that describes what Ben Shapiro means in FDCAYF is that ‘Rationality Doesn’t Care About Your Feelings’. But the line he draws between the rational and the emotional, as we’ve seen, doesn’t really work all too well. Practically speaking, when we’re dealing with issues as sensitive and important as politics, sometimes being emotional is precisely the reasonable thing to do.

Conclusion

Writing what’s essentially an entire essay on one single statement, on hindsight, might have been a bit of an overkill. But I do think there’s a lot to be said about FDCAYF and how it’s used. I absolutely agree that we should be looking at hard truths instead of what our ‘feelings’ would want us to believe, and I absolutely agree that people can sometimes get unreasonably emotional. But the truth isn’t as simple as that. Emotions aren’t something to be reviled and altogether avoided in politics, and we can’t separate facts from the ideological context that enables them to be political. And while Ben Shapiro and his followers aren’t particularly known for their attention to nuance, I think it is at least important that this nuance be known.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Marxist Analysis of Wall-E

Surprisingly, there actually are controversies surrounding this seemingly innocent family-friendly film, and criticisms of it ranging from "commie propaganda" to being fat-shaming. With all that being said, I thought it would be interesting to actually take a look at some of the ways in which Karl Marx's theories are reflected in the movie. However, based both on my reluctance to fan the flames of this (admittedly dated, mouldy and expired) hot potato, as well as the fact being fairly self explanatory, I don't wanna spend too much time on how consumerism is reflected in the film. For those who can't quite remember the premise of the movie, the basic idea is that corporations (like Buy N' Large in Wall-E) destroyed the environment and so humans were launched into space as part of a never-ending luxury cruise. Pretty simple message. What I find far more interesting, though, are the characters of Wall-E themselves, and how they demonstrate the Alienation that Marx thought capitalism would bring out in society. So - let's talk about robots.

Robots

So, the setting of the film revolves around the fate of the entire human race, with a casting of thousands of humans receiving screen time. Yet, it is a robot that is the titular protagonist of the film, and it is a robot that captures our hearts and with whom we empathise. Ironically, it is the robot that appears more human to us. Wall-E's actions drive the plot in the film, the entire conflict of the plot being borne from his own decision to befriend Eve and introduce her to the plant, his own decision to intervene with Eve's Diagnostics, and his own actions to save the plant. The only characters to enjoy a romance arc in the film are the two these two robots. In this film, rather than the humans, it is actually the robots who are the agents, and it is Wall-E, rather than the humans, whom we empathise with and treat as human.

Aliens?

Not a lot of Marx so far - just a general analysis of how the humans are backgrounded rather than foregrounded. Hold your horses, though, because this is the part where things get really spicy: we're gonna start looking at the humans' roles in the film.

As mentioned earlier, they are unexpectedly overshadowed by robots in a film that's inherently a critique of humanity. But this exactly plays into the point of what humanity has degenerated to in the film; they have become Alienated, in a way that Marx had predicted under capitalism. According to the Encyclopedia of Marxism, this Alienation is defined as 'the process whereby people become foreign to the world they are living in'. This symbolism is actually almost literally symbolised in the film. Think about it: the people in this film are literally foreign to earth. They have spent so many years in their sedentary space cruise that their very bone structure had changed, and when they finally touch Earth's soil for the first time at the end of the film, they arrive literally as aliens. The humans are literally foreign to the human world.

But outside of this little tidbit, the actual intricacies of Marxist alienation can be seen in other parts of the film too. In the Paris Manuscripts, Marx outlines four types of alienation one can face. Perhaps unsurprisingly at this point, they can all be seen in the film. So sit tight and buckle up, because we’re gonna be doing an ultra in-depth literary comparison between this children’s film and theoretical Marxist theory.

1. Alienation from Labour

Marx thought that, in order to avoid alienation, one has to work. To him, work gives meaning to someone's life. While I'm sure a lot of you all, myself included, would inwardly love to be able to live lavishly without really doing anything for it, Marx tells us that this isn't really what would make us fulfilled. Think about the pride one has in a job well done, or how we express ourselves through the creation of something (hence the word creativity). Marx's idea of fulfillment through labour, upon closer inspection, doesn't really seem that far fetched anymore.

Wall-E's humanity, however, are the furthest thing from hardworking people. They do not work, but rather spend all their days in casual leisure. They do not feel the fulfilment of hard earned rest, because there is nothing to earn. Everything is given. As such, they are denied access to the fulfillment of leisure because of their alienation from work, leading to their lives being droll, disconnected, unfulfilled and meaningless. Keep this in mind, because it is gonna be very important for the explanation of the other three forms we’ll talk about later.

2. Alienation from Products

Marx believed in an economic system that we call the Labour Theory of Value, in which the value of a product is determined by the labour that goes into it. Pretty simple, albeit very controversial today. But discussing the validity of Marxist economics isn't really the point of this post: let's get back to Wall-E.

The implications of the LToV get pretty interesting when we apply it to machines - let's say it takes a specific amount of labour to make a machine. Say also that this machine produces things. In the LToV, this means that the machine acts like some sort of storage for value: it holds all the value of its construction, and then slowly redistributed this value across the products it makes until it breaks down. Let's think about the machines in Wall-E: they're completely self sufficient, and have been for a long time, seeing as how human mechanics don't exist. They have been operating for such a long time that the products they produce have a greatly diminished value. Since we never really see the economics of the society there (if an economy even exists), we can't observe this greatly diminished value directly; however, this idea of the diminished 'value' of the goods in Wall-E is obvious from the way the humans treat the products around them. I think this is best represented in the first exchange between humans that we see. "Well then what do you wanna do?" "I don't know. Something." Leisure has lost its meaning, to the point where it is an end in itself, a mere passing of the time than a means towards unwinding, or as an avenue of self-actualisation. They sip at their lunch-drink nonchalantly, with no real enthusiasm for the meal, and only really greet the new release of clothing colour with mild, muted interest. Despite the supposed technological advancement of this civilisation, every new development in quality of life for the people just feels... unsatisfactory. We as the viewers feel nonchalance along with these humans towards their products, further highlighting the disconnect between the people in this show and the goods they consume.

Marx would associate this to the fact that, as mentioned in the earlier section, none of these people actually play a part in making these goods. Despite the fact that their entire world is constructed, none of them actually contribute to its construction. From the chairs they sit on, to the food they eat, to even the maintenance of the robots that create their chairs and food themselves, they have nothing to do with its production, leading to an alienation from the reality of their products, and a removal of fulfilment from an otherwise technically very luxurious life.

3. Alienation from other people

This one is a bit easier to understand, and in my opinion a bit more intuitive. Marx thinks a crucial part of the human identity comes from the individual's relation to other individuals, and the social connections between people. It kinda makes some sense: I think most people would agree that a big part of not being alienated would be having authentic relations with other people. This idea is particularly prevalent to us because of the technological and social context we live in today: I'm sure many of us (especially we interweb gremlins) can relate to technically having a lot of friends, but still feeling lonely. Having a ton of followers on social media, but still feeling like nobody likes you, still craving the authenticity that comes with a face to face, sincere interaction that doesn't have a computer screen dividing it. In a very real sense, a lot of us today are alienated in this way.

The society in Wall-E is kinda like an exaggerated version of that. They don't just impulsively look at their screens; their screens are their whole life. In the exchange I mentioned to talk about the alienation between people and products, that entire conversation ironically took place over a video chat screen, while both people were riding their chairs literally right next to each other. In this world, technology doesn't have to do the dividing for individuals: this division is made and maintained by the individuals themselves. In fact, throughout our entire introduction to the new human race, the only two times we see people outside of their trance-like fixation on their screens is when Wall-E's actions snap them out of it, from his confusion at a man passing him a cup, to him bumping a woman and accidentally shutting down her computer screen. The lady's expression of wonder at the world beyond her personal screen not only further proves this point, but ironically shows how even the oversized shopping centre that is the Axiom is a new world she was unaware of in her virtual reality. Other than Captain McCrea, this is the only time when we learn the names of any of the humans: it is only through the authentic interaction between Wall-E and John/Mary that we actually learn to ascribe an identity to them rather than treating them as part of the collective idea of "what humanity has become". As a whole, though, humanity under BnL was thus socially alienated from each other through technology, and therefore disconnected from the social reality that they live in.

4. Alienation from Humanity

Marx believed in something that he called humanity's Gattungswesen, or species-being. Humanity, at its core, was defined by their ability to objectify their intentions by means of an idea of themselves as the subject and an idea of the thing that they produce as the object. This all sounds very complicated and abstract, so I think it might help if we imagine an example for what Marx meant. The 19th century labourer to Marx was the hallmark of one who was alienated from their Gattungswesen, because they worked for their own survival rather than because they care about the product they are creating. In other words, they received wages for their labour, rather than profits, and hence were alienated from the Gattungswesen of acting in accordance to their own intention and conscious will.

So how does this translate to the labourless world of the Axiom? The alienation of the humans on the Axiom is made apparent when we look at how they behave in their own day to day activities. At first glance, it might seem like they are acting in alignment with their intentions: after all, with no work to do, they are perfectly at liberty to pass the time as they please. However, it is the very fact that there is nothing to do but to pass time that renders them victim to this form of alienation as well. Every form of recreation they do is as meaningless as the previous ones, just meant to dully stave off boredom as they while the time away. We don’t see anybody with hobbies, or quirks, or weird interests, but rather just a massive body of people doing little more than entertaining themselves to death. The story reaches its main conflict only when McCrea realises his own identity, and defies AUTO’s directive instead of meekly complying as he used to, thereby reclaiming his own agency and actually cementing his intentions into action and will. In a sense, the turning point of the story was bolstered by the fact that humanity has begun to realise its own alienation from Gattungswesen, if only at a subconscious level.

This separation from humanity is shown in a metaphorical sense as well, through the dichotomy that the film draws between the natural and the artificial. The natural is seen as authentic and mysterious (like the plant) while the artificial is portrayed as sterile and detached (BnL). It is ironic that the Axiom, itself the hallmark of this artificiality, has a beach simulation section that people are shown to visit, despite the fact that the people on the ship have no knowledge or experience of a real beach to begin with, symbolising what Marx might see as the perversion of and detachment from humanity’s Gattungwesen. Even more ironic is the fact that the people who visit the beach don’t even seem to notice their environment, instead staring at their screens in the exact same manner the people in transit, or eating food, or doing otherwise mundane things do. A trip to the beach on the Axiom is basically as meaningful as waking up and brushing your teeth, further demonstrating the subversion of any authentic appreciation for the “natural” home of mankind. In fact, the story’s optimistic end is marked by humanity’s return to Earth, demonstrating an overthrow of their oppressors (the BnL Artificial Intelligence) and a return to the organic, natural world, mirroring humanity’s connection back to its nature.

Conclusion

To be honest, I genuinely think that Wall-E is one of the most well written and complex social criticiques that Disney has ever created. This entire post only analysed a select few scenes where humanity was foregrounded, and didn’t even do any analysis on the truly juicy bits like Wall-E’s characterisation, or the religious undertones prevalent throughout the film, but it still ended up being this long. Of course, I don’t genuinely believe that Wall-E is some sort of communist fearmongering propaganda. I just thought that it might be interesting to see how Wall-E could be appreciated through a Marxist lens without necessarily descending down the “boo capitalism” spiral that’s undoubtedly already been done ad nauseum.

#wall-e#walle#philosophy#literature#analysis#film#film critique#film analysis#literature analysis#marxism#marx#karl marx#alienation#existentialism#disney#pixar#text spam#dumb analysis

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysis of ‘mother!’

About a week ago, I went with a friend to watch Darren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller ‘mother!’. Truth be told, I’m still recovering. Aronofsky and Jennifer Lawrence themselves did mention that the show wasn’t for everyone, and I understand why they would say so; the show is prodding, uncomfortable, and excruciatingly persistent in discussing what it wants to discuss. But I’m not just saying this because of its controversial portrayal of religion and Christianity - I’m pretty sure the internet has already been flooded by discussions on the matter by now. Instead, I wanna talk about how it deals with one of the concepts I personally hold quite dear to my heart: pacifism. Spoilers ahead, of course, so I’d recommend you watch the movie before reading this post.

Angel In The House

Let’s first talk about the portrayal of Jennifer Lawrence’s character, since she’s probably the most pacifistic and passive character in the movie (at least, in Act I). She represents an old Victorian literary trope that Darren Aronofsky revives in his movie, called the ‘Angel in the House’. This is basically the archetype of the domestic goddess, the pure and virtuous wife who brings life and beauty into the household, the compliant angel who glides through the house performing her domestic duties. Essentially, the Angel in the House is the Victorian ideal for everything a woman ought to be. We can see this being represented to the letter in Lawrence’s character (henceforth referred to as Jenny for the sake of brevity). When Jenny is by herself, she is often seen performing household chores like painting a room or washing the clothes. Even more telling is her lack of identity except in relation to her husband. He can be seen to have a job, and leaves the house multiple times. Jenny never does, and can be assumed to be a homemaker. She and the house are actually actively paralleled, with the house constantly mirroring her state of mind, especially during her breakdowns when the house itself shakes. The hole in the floor disappears once the domestic conflict that Adam and Eve bring about is resolved, and the house itself actually physically breaks when she finally loses it in Act II. In fact, the only times she actively requests to leave the house are when He puts her in uncomfortable, destructive situations: once when Cain had just left the house and was probably going to return, and when the house was invaded by cultists worshipping her husband, ‘Him’. Yet, every time, her requests are denied, and she readily complies. She never actually leaves the house. The notion of her being the Angel in the House itself already symbolises compliance, meekness and passivity. The fact that she actively keeps herself within that role from the instruction of her husband seals her identity as the representation of these values. She isn’t going to be a Nora or a Lady Windemere; instead, she remains, for the greater part of the movie, blindly compliant, blindly passive.

Passivity to Pacifism

This is the part where we make the jump from her representing passiveness to her representing the values of pacifism. You can probably already see the links; pacifism in its garden variety is essentially a moral code based on passivity, but the jump requires moral conflict. Aronofsky provides Jenny with plenty of these, and often in explicitly violent terms. We see Cain beat his brother to death, we see Jenny forced to witness the death and gruesome consumption of her child. Even her rebirth involves the tearing out of her heart. In other words, Jenny is subject to violence throughout the movie. And for all the damage the various characters wrought on her house, for all the harm that came to her, she simply turns the other cheek. In fact, when Cain confronts her and aggressively justifies his innocence to her, she simply cries and nods. I’m not saying that this isn’t a reasonable action to take in that circumstance; hell, if some guy cupped my face in his blood-soaked hands and demanded if I understood the rationale behind his murder, I’d probably do the same thing. But the fact that this was explicitly slid into the scene rather than making Cain simply just leave there and then does more than to add realism. It characterises Jenny as one who is most comfortable sitting in the backlines, accepting and enduring all the wrong done to her and within her house; it characterises Jenny as both passive and pacifist.

Of course, she isn’t ALWAYS passive. She finally snaps and turns violent at the sight of her child being eaten, massacring the cultists who engaged in the perversion of the Holy Communion. In fact, she refuses to allow Him to carry her baby out to the crowds in the first place, the first act of disobedience she actually makes in the movie. That’s where the importance of the baby comes in. The common idea of what the baby represents is that he’s supposed to be Jesus. And of course, that’s definitely the case. But evidently, using that definition alone doesn’t really do justice to what the baby means to Jenny. All her major character developments are done in relation to the baby; she flushes her painkillers down the toilet bowl after she becomes pregnant, a resolution to her inner conflict that arose from the intruders in her house; she takes a stand against Him when he demands her baby, and she finally descends to pure rage at her baby’s death. Ultimately, the baby is Jenny’s motivation. It is goodness, purity and innocence. And that’s exactly where Aronofsky’s critique of pacifism lies.

What All This Means

What Aronofsky presents to us in mother! is the self-defeating and hypocritical nature of passive pacifism. It’s not just that you’ll eventually snap and get sick and tired of being kicked around; it is about justice. Think about it; if nobody is there to enforce right and wrong, who’s there to uphold the notion of rightness in the first place? In a morally bankrupt world where fans eat babies and the poet simply watches as his own son gets torn to shreds, how can one simply stand back and watch as the individual’s and the world’s purity becomes corrupted, and simply offer up your other cheek? I’ve read some complaints that the characters in the movie are unrealistic, but I frankly think those criticisms just show a lack of awareness of what mother! was trying to do; subverting reality is the whole point of the movie. In this world, everybody is compliant and everybody is passive: even God. There is no individuality among the cultists, and completely no objection to the consumption of the baby’s body. They even just stand there meekly like sheep as Jenny culls through the herd in her rage. ‘He’ himself says that ‘I don’t want them to leave’, demonstrating his wilful ignorance of the cultists’ evilness in his desire to be worshipped. Even the non-passive characters, like Cain and Eve, bring nothing but harm to the homestead when they act of their own volition. In a world like this, the supposedly moral act of letting evil acts pass unjudged ironically breeds more and more evil. Ultimately, pacifism ends up morally corrupting itself, just as Jenny, in her inability to assert her will, eventually burns down her own house in her fury.

The idea of moral passiveness often has links to religion. God is the arbiter of the just and unjust, and men have no right to enact their own flawed moral compasses as the ethical standard. John 6:37 - Judge not, and you shall not be judged. Instead, what we should do, as Matthew 5:39 puts it, is simply ‘not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also’. But if God himself is passive, if God himself lets injustices continue in the world without punishment, then who is left to make sure that goodness prevails? mother! is often interpreted as a religious allegory, and that’s of course the canon and mainstream reading of the movie. But through its treatment of the religious, I think Aronofsky might be getting at a more moral, more tragic message against sitting in the backlines and simply taking everything in stride. Because that doesn’t just hurt you. It hurts everyone around you too.

This is not to say that pacifism or religion isn’t justified. The last thing I want this article to be seen as this edgy rant on the ‘inconsistencies of Christianity’ or ‘how Christianity makes you weak’ or whatever. I myself am a Christian and largely identify as a pacifist as well. But maybe that’s why this movie left such an impression on me. Of course, this isn’t exactly a matter of critiquing pacifism as a whole. You can still be against violence without being guilty of the hypocrisy that Aronofsky describes here. But what I think he’s really trying to get at is moral and personal passivity, the idea that standing back and letting things just run their course is somehow the right thing to do. And the justification for this is always that ‘my moral judgements may be wrong’, or that ‘it’s not my place to rock the boat’, or even ‘who am I to judge?’. Far too often, we simply dismiss our lack of courage to do something about injustice by hiding it under the guise of ‘simply wanting peace’ and ‘never resorting to violence’. But that really isn’t what being a good person, or even being a pacifist, is really about. And I think we all need to start acknowledging that - even though it isn’t always wrong - the fatalistic commitment to inaction itself is a conscious decision that we cannot shirk responsibility from.

#mother#jennifer lawrence#darren aronofsky#ethics#ethical#movie#movie review#pacifism#passiveness#god#victorian#critique#mother!#food for thought

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Talk About Rights

The recent controversies surrounding NFL have raised a lot of talk about rights, and the way people use them. Supporters of the athletes claim their right to the freedom of speech, while critics say that it is disgraceful that Americans disrespect the flag. Yet, the whole notion of what a ‘right’ even is, and what having rights mean seem to be pretty unclear when debates on the issue actually arise. Far too often, we see debates about rights degenerate into a bipartisan squabble, an exchanging of insults between right wing and left wing, and we all know how unproductive those things turn out to be. Rights can be pretty difficult to pin down, and even today the nature, implications and even existence of rights are being debated in universities and courtrooms. But there is one very important model of rights that I think applies itself very well into understanding the current political climate. It does not profess to tell you what rights exist and what rights do not, but rather clarifies what is actually meant when one claims to ‘have a right’. This model is called the Hofeldian Analysis.

Talk of rights inevitably comes up any time politics does. We hear it everywhere: the right to life, the right to free speech, the right to fair trial. But one thing that the political rights theorist Wesley Hofeld noticed about rights is that they are always made up of certain components. Think of it as something like molecular bonds; just like how water is always comprised of an ordered structure of H2O, rights are comprised of certain ‘Hofeldian incidents’, qualities that define what the right actually means.

Positive and Negative Rights

Things get a bit technical from here. Rights can be split into two large groups: positive and negative rights. When I have a positive right, it means that I have a right to impose something on you. For example, if I say I have the right to my wages, I’m saying that I’m justified in imposing on my employer that he pay me my due. Negative rights are when I have the right to impose that you can’t do something to me. If I say I have a right to life, I can impose that any prospective murderer not kill me. Notice how every right necessarily involves another party? In these examples, they are the employer and any prospective murderers. That’s the beauty of the Hofeldian Analysis; it involves both the subject and the object of the right. There’s no point in claiming my supposed right to free healthcare if nobody is there to give it to me.

The Actual Hofeldian Analysis

Noticing this, we realise that each right corresponds to some sort of ‘power’ given to the owner of the right, and a behaviour that some second party must do. This is the part where the Hofeldian incidents come in. Let’s take the earlier examples. When I say that I have a positive right to my wages, I’m asserting that I have a claim over my employer. Likewise, because of this claim, my employer has a duty to pay me. Conversely, when I say that I have a negative right to life, I’m stating that I’m at liberty to live. Therefore, any prospective murderers have no-claim to kill me. You can see it a bit like the GATC bonding in DNA. G has to bond with C, and A has to bond with T. Likewise, a claim must always be followed by a duty, and a liberty must always be paired with a no-claim. These are the first order rights of the Hofeldian analysis. Second order rights are about being able to modify the rights of other individuals in society, but that can wait for another post. This will do for the purposes of discussing most of the social issues we talk about today. The first order rights alone hold huge implications about how we should view rights and how we should advocate for them; when we say that minority races have the claim to equal opportunity, whose duty is it to respect that claim? Is it the government? White people? Corporations and employers? We don’t often think about the ‘receiving end’ of rights, but different answers could have very different implications, and learning to identify the right one could be the difference between an effective solution and a well-intentioned but unsuccessful flop.

How This Applies To The Current Situation

Let’s bring this back to the situation at hand; the NFL debacle. Using the Hofeldian Analysis, we can have a clearer picture of what’s going on; the NFL athletes and their supporters are asserting their liberty to freedom of speech, a liberty that the NFL organisers (and the rest of the American populace) have no-claim to infringe on. In response, critics are saying that the athletes instead have a duty to respect the American flag, imposed by the upholders of the flag’s dignity, i.e. the American government. It really is a matter of two conflicting rights.

With this in mind, what we really need to ask is about which right supersedes the other. Is it really true that the flag, and - by extension, the USA - has a claim over the athletes’ respect? Is it the case that, no matter how messed up a country or its government becomes, it is every citizen’s duty to be proud of it? The act of taking a knee is meant to symbolise a stand against oppression and discrimination, and I think that it’s perfectly reasonable to express a loss of respect for one’s country on that basis. It’s pretty inarguable that those who refused to salute in Nazi Germany should be commended for their courage and independence of thought; some may even call them the real German patriots for believing in a better, more humane Germany. I’m not saying that Trump’s government is fascist or Nazi or any of that; instead. Instead, I simply want to address the notion that the Flag’s claim to respect trumps freedom of speech.

Think about it; by denying the players the right to take a knee, we aren’t just defeating the whole point of free speech, but also the value that this respect for the flag entails. To me, condemning the NFL players for their actions is frankly quite self defeating. The very notion that loyalty to country is more important than an expression of belief in itself already sounds pretty dystopian; but given this, if anybody were to claim that the NFL players should be punished, if President Trump wants to find legal and moral grounds to fire the NFL players for whatever iteration of treason he thinks they’re committing, they would need a very compelling reason as to how this arbitrary idea of patriotic respect is more necessary, more significant and frankly more American than the whole basis of having a right to free speech.

#NFL#Controvery#Trump#Rights#Philosophy#Hofeld#Takeaknee#Jeff Sessions#Politics#Political#Political philosophy#theory#america#current affairs#anthem#flag#minorities#rant#ranting

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is Morality Just What’s Best For Society?

One of the most difficult questions to answer in morality is just simply where it comes from. What exactly makes something ‘morally good’? How do we tell when something is good? What even is morality?

I think this remains the single most important question we should be asking when we talk about morality, since it really reveals the underlying assumptions and the very basis of what you mean when you refer to morality in the first place. And of course, as we’ve seen time and time again in history, misdirection and misunderstanding in ethics can have pretty disastrous consequences. This issue in morality, the uncertainty of its provenance or origin, is called ‘the grounding problem’.

So. A pretty popular and intuitive answer to this issue that I hear lots of people support is just to say that whatever makes the most number of people happy, or the pursuit of whatever is the ‘greatest good’, is what morality ultimately is about. In other words, moral goodness is the same as social goodness.

This is pretty similar to a really popular ethical framework called Utilitarianism, which argues that goodness is simply maximising utility, or happiness (people who study economics would find this term very familiar). To be more specific, it is quite similar to Jeremy Bentham’s Act Utilitarianism. According to him, ‘Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters: pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.’ In other words, we can achieve maximum happiness by maximising pleasure and minimising pain. Fair enough. Pretty intuitive.

Yet, this view might seem a bit overly simplistic. When I first read it, I thought something seemed off, fishy, even a bit sinister about it. So morality is literally just whatever serves the greater (well, greatest) good? We’ve all seen how that sort of thinking can go south really fast.

As I’ve already written about in this post, I personally think that happiness can’t serve as a good indicator for the grounding of morality in the first place. But when we say that moral goodness is literally just whatever serves the interests of the largest number of people, we can get some pretty worrying answers to the practical ethical dilemmas we face in everyday life.

Let’s say you’re a surgeon, with 5 terminally ill patients who all need organ transplants. The organs they need are all different, and the hospital doesn’t have any supply left. According to Act Utilitarianism, or anybody claiming that social goodness is the same as moral goodness, it is not just morally justified, but morally praiseworthy that you go out with a knife, stab an innocent man to death, harvest his organs and save your 5 patients. After all, you reap a net benefit of 4 peoples’ lives, and the total pleasure of 4 peoples’ gratitude at not having to die from some painful, debilitating affliction. I don’t know about you, but that doesn’t seem very right to me. Even if you argue that allowing such behaviour would just lead to justified murder and the breakdown of society, and so ultimately isn’t socially constructive, what if the surgeon does it in secret? If nobody finds out, this act wouldn’t be popularised, and none of that apocalyptic destruction of society and rampant murderous surgeon stuff would ever come true. Even so, even if the surgeon pulled it off in secret, doesn’t the murder of an innocent man on the street, the sacrifice of a perfectly functioning, morally conscious agent for the ‘greater good’, just seem... wrong? The very fact that this must be conducted in secret already makes it hard to swallow that this can in any way be a standard for what moral goodness means.

Let’s talk about another example, one raised by contemporary philosopher T.M. Scanlon. Say you’re working at a TV broadcasting network which is currently airing the FIFA grand finals. Millions are watching. There’s just one problem: your coworker, Bob, has encountered an accident. A transmitter has fallen on his arm, and you can’t get it off without turning it off for 5 minutes. However, if you did, the show would be cut off for that duration of time. I’d like to think that any decent human being would just help his friend out and maybe get the PR team to issue an apology. But that’s not what an Act Utilitarian would do. Millions of people are watching. Granted, the pleasure someone gets from watching the show is pretty tiny compared to the pain that Bob is feeling. But when you multiplied that tiny little amount of pleasure by the millions of people watching the show, it seems like we really shouldn’t be saving Bob at all. We’ve gotta wait for the whole programme to finish, leaving him writhing in pain on the ground, before we’re even morally allowed to help him. In fact, why can’t we just go to the full extreme of this example? Say the transmitter fell and broke Bob’s ribs, and if you don’t save him within the hour he will die. But let’s also say that literally the whole world is watching the show. What’s one puny little human life compared to the 7 billion’s entertainment? The show must go on. If we wanna say that moral goodness is also social goodness, well, I guess the only thing we can really do is just say our farewells to Bob.

Can utilitarianism be supported? Absolutely. Plenty of great ethicists are utilitarians; it is one of the largest moral traditions in the history of academic philosophy. John Stuart Mill, widely considered to be the founder of modern day liberalism, was what he called a Rule Utilitarian. Even modern day philosophers, like the famous animal rights advocate and professor at Princeton Peter Singer, says that he bases a lot of his work on a modern take on the tradition called Hedonistic Utilitarianism (trust me, it really isn’t as dumb as it sounds). I don’t really consider myself a utilitarian, but I’ll admit that there are some pretty good reasons to be one. But when we choose to define moral goodness as social goodness, when we choose utilitarinism in its purest, most unqualified form, when we choose to look at morality as Act Utilitarians, we arrive at some conclusions that I think any rational, decent human being would genuinely find quite hard to swallow.

#Utilitarianism#ethics#society#morality#bentham#philosophy#john stuart mill#peter singer#rant#ranting#consequentialism#morals#ethical#social

1 note

·

View note

Quote

I see it all perfectly; there are two possible situations — one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it — you will regret both.

Soren Kierkegaard, Either/Or

#kierkegaard#soren kierkegaard#life#absurdism#existentialism#existential#regret#pessimistic#pessimism#motivation#either or#advice

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brave New World, Veganism, and Psychopaths

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley is honestly one of the most well-written and thought-provoking books I’ve ever read. It’s one of the books I’d been working on for a paper on religion in dystopia (Fahrenheit 451 and the Handmaid’s Tale being the other two), and rereading it has just made me fall in love with the book all over again. People seem to always see Brave New World in contrast to 1984 – and, of course, that’s a perfectly justified and good way of looking at the themes in Brave New World – but I think the beauty of the book only really shows when you look at the story on its own. There’s just so much to be said for Brave New World; you could analyse its notorious portrayal of propaganda and political control, its discussion on the nature of religion, and even its real-world cultural critique, and still not fully wrap your head around this book.

That’s way too much for me to cover in one tiny blog post. Instead, I want to talk about the most in Brave New World is the part of it that I found the most unsettling, and the part that most changed my life and the way I see things: Aldous Huxley’s commentary on the ethics of happiness.

Huxley’s World State Society is somehow both my utopian dream and also my worst nightmare. Wars are a thing of the past. Humanity as a whole has finally managed to look past its petty differences and stand united. People aren’t just happy; they are born and bred happy.

Wait a minute. That doesn’t quite sound right. Born happy? Well, that’s the catch to this society - people don’t reproduce per se. Having a natural birth is considered immoral and repulsive. Instead, babies are cultivated and grown in Hatcheries, and are given a predetermined class. The Alphas are grown and genetically modified to be the elite, ruling class, while the Epsilons’ growth hormones are sabotaged to create half-imbeciles who serve to be the bulk of the working class. Everybody is conditioned to love their own class, and feel a healthy amount of condescension to every other class that they do not belong to - though not enough to breed hatred for them. In other words, there is perfect social stability. Literally everyone is happy.

There’s something strangely unsettling about that which is kinda hard to describe. To better put it into words, I like comparing it to philosopher Julian Baggini’s thought experiment about the Pig That Wants To Be Eaten. Farm animals live really terrible lives, as we all know, and it wouldn’t be controversial to say that their treatment is highly unethical. But what if we could genetically breed pigs that want to be eaten? Rather than them having a vested interest in surviving, every pig’s dream is simply to live in a clautrophobic pen, fatten up and be taken to the slaughterhouse. Would that make their treatment any more justified? Would this convince an ethical vegetarian to try pork once more?

I know that this example can be rather hard to relate to if one doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with killing animals for food, so let’s change the example a bit. What if, to satisfy humanity’s inner sadism and the frustrations of life, we breed some people to be suicidally masochistic? For these people, their greatest aspiration is to be painfully beaten and tortured to death for the sake of the catharsis of others. Can this justify their torture in any way? Psychopaths and serial murderers would finally have some willing playthings, and humanity would have yet another fulfilling source of entertainment. In fact, since two parties instead of one would be enjoying it, why shouldn’t we be encouraging this?

And that’s exactly why Brave New World so creepy and dystopian. When we think about morality, it can be pretty easy to summarise it as whatever makes people happy. Happiness is viewed as the be-all and end-all. Even in our lives, most of us just want to be happy (at least, that’s what we most often tell ourselves). And that’s a perfectly noble and justifiable goal. But when we chase after happiness, or use happiness as a metric for morality, or even when we think about what makes us happy in the first place, Huxley seems to be asking his readers one often forgotten, uncomfortable but crucial question that I think defines the whole of Brave New World:

How much of ourselves are we willing to sacrifice to be happy?

#ethics#julian baggini#brave new world#book review#rant#ranting#fanboy#book#happiness#life#philosophy#thought-provoking#morality#dystopia#utopia

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Morality Matters

‘Why should I be a good person?’ ‘What’s the point of doing the right thing?’

'Why does morality matter?’

Lately, I’ve had a lot of trouble trying to answer these questions. Sure, there are plenty of offhanded, easy answers out there. Do it because people will like you more because of it. Do it so you wouldn’t go to Hell. Just do it because it’s what you’ve always been doing.

But as compelling as these reasons are, they don’t really seem to tackle the point of morality. There are so many situations out there where doing 'what is right’ makes you more disliked, or makes you do something you don’t usually do. As for the whole religion and Hell thing, well… let’s just say I don’t really think morality is reserved exclusively for non-atheists, and that there are plenty of atheists out there who do lots of good for the world and the people around them too. I’m not really convinced that these are the reasons why morality is so important.

We can’t just screw everything and say that morality doesn’t matter either. Just think about a world where morality doesn’t matter. It’ll literally be the Joker’s paradise; thievery, murder, sexism and racism, everything we consider deplorable and morally repulsive would be fair game. We would have no grounds to condemn any of these. All the social change humanity has pushed for, the abolishment of slavery, desegregation of the blacks in America, the fight for minority rights - all of it would be meaningless. Unless we’re prepared to accept all of that, we can’t really say that morality doesn’t matter either.

Tough luck.

So here’s what I think. It’s a pretty anticlimactic response, but I think it works nonetheless.

The question is complete nonsense.

Think about it. When we ask 'Why should I do the right thing’, what we’re really asking is 'Why should I do what I should do?’ The right thing is, by definition, what we should do in any given circumstance. It’s just as nonsensical as asking 'Why must 1 be 1?’; by definition, it just is.

I recently managed to get my hands on a copy of The Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant, and in it he talks about the 'good will’: the rational and benevolent commitment and intention to do what is moral. According to Kant, it is the only thing that is good without qualification. We could say that education is good because it increases your chances of getting a good job or living a more pleasant life, but then the good of education is from its effects and accomplishments. It is not good in itself. Even happiness is not good without qualification; happiness at the expense of others, or even at the expense of yourself like in addiction and debauchery, cannot be said to be 'right’ either. In other words, happiness itself is not right or good without good will.

Going by what Kant says, it seems like a lot of those questions can be answered to a greater extent than semantic wordplay. To Kant, the question of whether morality matters is not just nonsensical; when it comes to doing what is right, quite literally doing what you should be doing, morality is really the only thing that matters at all.

6 notes

·

View notes