Joe Scanlan is an artist and writer whose work takes multiple forms, from sculpture and design to publications and fictional personae, and is internationally renowned for his dark humor and conceptual rigor. Scanlan is currently a professor in the Visual Arts Program at Princeton University. http://wwwjoescanlan.biz

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Fine Disregard

Syndicated from Joe Scanlan’s website.

It’s not often that you can talk about objects that both move through and contain public space. Conventionally, public space is any area in common use by converging groups of people. Only in vehicles does this convergence move, and whether on a skateboard or a motorbike, in a car or plane, one of our most sublime sensations is the feeling of being at rest at a point in space that is in motion, a thrill that is accentuated when we position our bodies in such as a way as to become at one with our vehicle. As such, vehicles present a great opportunity for looking at the relationship between new products and human behavior, and how innovative design and the will of the people get played out in public space. Los Angeles is perhaps the pinnacle of this kind of play, a free-flowing, kinaesthetic agora of vehicular identities that I love to look at but to which I cannot relate.

I’m much better at relating to subway cars, because, well, that’s where I get my oneness. That’s why I’m so excited that the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority is getting a new car. In fact, there are two: the R110A designed by Kawasaki Heavy Industries (Japan) and the R110B, designed by Bombadier Transit Corporation (Quebec), both of which are being used on a trial basis and from which an “ultimate” subway car will be designed. Superficially both the R110A and the R110B are cold and impermeable-looking, yet their petroleum composite floor, plastic seats, brushed aluminum fixtures and stainless steel shell all evoke an accommodating, low-level cyborg kind of charm—a charm enhanced by center-hung LED information boards and a computer-automated female conductor’s voice. The fact that there is no longer a human being announcing stops or working the doors is even more efficient than would be expected, and only underscores the material impression that, over time, these cars will not be cleaned so much as pasteurized.

This icy seduction is epitomized by the R110A’s seating arrangement, which is as conceptually beautiful as it is psychologically appropriate. Unlike European subway cars, which are arranged in cozy, inward-facing booths, or New York’s older cars with their two opposing rows of seats like a gauntlet, those of the R110 A are arranged so that only four seats in the entire car face each other. Eye contact, which is practically mandatory in older subway cars, has been averted; for the first time, a design feature ensures you no longer have to lower your eyes or raise your newspaper to avoid being faced. In practice, it turns out that the seats along the wall fill up first because those are the only ones where your back is covered; the most provocative are the two seats nearest the door, the first being parallel to the exit and the second perpendicular to it.

When you sit in the second seat you face the profile of the person sitting in the first who in turn faces the person on the other side of the aisle, like three people demonstrating a Feng Shui concept or posing for an Obsession ad.

It is impressive when such keen human insight gets built into the body language of a product, but especially when these insights are not entirely flattering. The R110A is the first subway car design that not only recognizes but encourages our avoidance of each other and makes reasonable—even palpable—the human chess match we’re all in, ultimately creating a more fluid, co-existent kind of .. . courtesy? Mind Control? I’m not sure. I only know that it is slightly disturbing to enter one of these cars for the third or fourth time and begin to suspect that, no matter how full or empty it is, the car seems to anticipate and then coerce your move based on the structural logic of where it has placed everyone else. It is as if some new kind of information has influenced the layout of the car and that you personally have had something to do with that learning process. When? How? Is that creepy or what?

Alas, we live in democratic times, and the MTA has informed me that the R110A’s seating arrangement will revert to the former gauntlet style because too many riders complained about a lack of seats. I wonder: did people complain because they wanted to sit down or because, being Americans, they didn’t want even fewer people than usual to have something that they couldn’t? Once again we regress to the familiar, not on the basis of its merits but because it puts the most people at ease. I guess George Clinton was right when he said “give the people what they want, when they want, and they wants it all the time.” However vexed we were by modernist ideology, the products resulting from the current consensus-based, consumer-driven service economy are really starting to depress me. I miss having to accept something whether I like it or not, if only for the bits of stunning genius that that single-mindedness made possible. OK, the R110 prototype is no Citroën DS or Salk Institute, but it is a pleasure I didn’t request or have to submit for committee approval. Consumer culture, where is thy victory? Product, where is thy sting?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ethics of Ambiguity

Syndicated from Joe Scanlan’s website.

Ice hockey is a cruel game. Unlike other international sports involving a projectile of some sort, at no point in a hockey game are you guaranteed possession of the projectile. After every goal in soccer, touchdown in football or basket in basketball, the rules stipulate that the other side get a chance to do something with the ball. In tennis, volleyball, and other net and racket sports, this even-handedness actually mandates that it is only after you have delivered the ball to your opponent, and it is clear that no response is forthcoming, that you are deemed to have scored. Even baseball—whose disregard for time and scoring limits allows that every game has the possibility of going on forever—is nonetheless structured around alternating possessions regulated by set numbers of innings and outs. Change of possession is the fundamental punctuation of most major sports, providing each with its sense of drama as well as demonstrating its particular concept of fairness.

In hockey, on the other hand, the puck is brought back out to center ice after every score for a free drop between two players, one from each opposing team: the face-off. In theory, if a hockey team had an indomitable face-off artist, errorless puck handlers and an expert scorer, they could play an entire game within the rules of the sport with their opponents ever touching the puck, save for the goal tender fishing each goal out of his net. (And he isn’t even required to do that, although he usually does.) No other sport that I know of allows for such utter dominance and frustration.

And if this frustration is the reason why there are so many fights in ice hockey, then it is also the root of why the game is not popular from a purely visual standpoint. Fringe observers and media experts have said for years that hockey is as frustrating to watch as it is to play, that it suffers from erratic and irregular “possessions” of an object that is either too small or moving to fast to be seen. This is certainly true if you’re concerned with following the puck—a black, solid rubber disct measuring about three inches in diameter that frequently approaches speeds of 90 miles per hour—but this obsession with the ball, endemic to other televised sports, is not so relevant in hockey. Hockey players may be the only professional athletes who will admit that often even they don’t know where the primary object of their game, the puck, is. They’ll also tell you that this confusion is part of hockey, something to be seized and made use of. I’m not much of a hockey fan, but I’ve always liked this aspect of the game, the thrill of momentary loss of content, of possession, of vision. You see these people racing around and yet you can’t see the point of it all, the subject of their desire—the puck. To be a fan or player of hockey you have to develop an absurdist’s resolve, acquire the ability to continue watching or skating even when the objective is unclear. In such moments your only recourse is to scan the ice and figure the common vector of all of the player’s gazes, dabble in Cluster Theory and analysis, or as a shortcut, check the goalies. A goalie’s posture will always tell you where the puck is, and if it doesn’t, then he is about to be scored upon. Either way the game’s objective will be made clear.

Unfortunately, American television networks haven’t been interested in televising such non-productive ambiguity since they stopped broadcasting hockey in the early 70s. Such programming tends to make viewers uncomfortable with their sets, gets them thinking about how they might spend their free time better, what’s for dinner, when they will die. National Hockey League commissioner Gary Bettman blew the issue wide open recently when he revealed that the reason hockey hasn’t worked on television is that the dot matrix that comprises a video image is absolutely incapable of depicting a puck that is moving at more than seventy miles per hour—which happens about fifty times a game. As he described it, the puck virtually “disintegrates” within the system, like an image halftoned into oblivion or a comet entering our atmosphere. This was a disheartening realization for viewers who expect a lot from their television sets, not to mention those who need people to believe in the medium’s omniscience.

Enter Fox Television, the new network provider of professional hockey, who does not share my enthusiasm for formlessness and ambiguity. With the commencement of the NHL playoffs, Fox unleashes a video imaging technology known as FoxTrax, which promises to eliminate the anxiety of watching hockey on television. They system works by first embedding twenty miniature, high impact, infrared-emitting diodes around the circumference and the top and bottom of the puck. Second, an impermeable surveillance grid of infrared sensors is installed on the walls and over head structures surrounding the ice rink, the information from which is linked via computer system to the video output of the game. When the new “cyberpuck” is put into play, its exact location is tracked out on television screens by a surrounding blue “aura,” an aura that penetrates players, goalie pads or the near boards, like the “you are here” indica tor on a subway map. Whenever the puck exceeds seventy miles per hour in the course of the game, the computer automatically converts to a red “comet tail” indicating its speed and direction. When the puck drops back below seventy miles per hour—reintegrates, so to speak—the blue halo returns. Thus there is not a single moment in the life of the puck that goes unmonitored, not even when it is hidden or “disintegrates.” Its only escape is to leave the playing surface altogether.

Having broadcast the system as a trial run during the NHL All-star Game, FoxSports tells me that it received an enormously favorable response. I believe them. In a country where seven year-olds routinely wave at bank security cameras, where prisoners are detained by electronically monitored bracelets, where you can dial a 900 number to find out if any convicted sex offenders have moved into your neighborhood, where a detailed computer image of your building is readily available on the target screen of every jet fighter in the military (and isn’t that great), always being able to know the location of the puck is a disturbingly trivial thought. Americans love being monitored, and they rely on their television sets to fulfill that task more than any other component of their lives. Whether watching or appearing on talk or home-video shows, or filling out Neilson Ratings forms, people believe—have seen proof—that they are integral to television’s existence, not only by sitting home and watching but also by providing it with content. Before FoxTrax, the loss of the puck in televised hockey revealed a fatal flaw in the medium’s coverage that threatened to undermine the confidence of viewers, implying that their were still people and things in the world capable of moving through the system without a trace. Now the once dazzling inanity of computer technology has staved off pangs of insecurity and death, at the same time annihilating the must subtle and admirable aspects of a minor competitive sport.

0 notes

Text

Collier

Syndicated from Joe Scanlan’s website.

There once was a person named Schorr,

Who thought that she’d been here before.

So she called up a clerk

And without too much work

Got a file on the Schorrs of yore.

While reading the file in her parlor,

She discovered another Schorr, Collier,

Whose identity it said

could be easily had

Through a letter, enclosed with one dollar.

She mailed the letter on the twelfth,

Put the file away on a shelf,

And was greatly relieved

When she later received

The letter, addressed to herself.

*

unpublished correspondence with artist and writer Collier Schorr.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Curates: DIY

Syndicated from Joe Scanlan’s website.

Although many artists can be said to contemplate mortality in their work—usually in a veiled, Robert Frost kind of way—a clearheaded few have cut through the allusive haze and made their contemplation plain. Whether natural selection, mercy killing or suicide, intimations of death have gotten artists through many a hard night. Sensing her failing beauty and waning political influence, the Countess Castiglione posed for The Foot, one of her most touching and sardonic images. Kazimir Malevich designed and painted his own coffin without compromising his aesthetics or his politics. His austere Suprematist box suggests that the beauty of having a formal ideology is that you can take it with you.

Staging death has also been an effective way for artists to express a wish, foment resistance, or change careers. They have posited death in the form of crystalline inertia (Robert Smithson), weightless dispersion (Andy Warhol), theatrical entombment (Paul Thek), subterranean surveillance (Bruce Nauman), ritualized grief (Gordon Matta-Clark), or delusional grandeur (Bas Jan Ader). For each of these artists, the metaphor of death promised a subversive alternative to the equally fatal obligation of producing yet another signature work.

Today artists no longer face this dilemma between their integrity and the demands of the culture industry. In fact, making reliable works of art now requires that artists sacrifice themselves as beautifully as possible. General Idea serves up giant placebos of themselves, David Hammons masters kicking the bucket, and Maurizio Cattelan digs a grave just as he is becoming a star. In a time when art gets subjected to the same numbing cost analyses as IKEA shelving units, a little death homeopathically injected into the system might be just what our culture needs.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Man for Himself: Henry Darger

Originally uploaded on Joe Scanlan’s website.

One thing is certain: commentaries on Art are the result of shifts in the economy.

– Marcel Broodthaers

Imagine it’s 1970 in Chicago, Illinois. It has been rough going lately for the city’s independent record labels—what with the corporate monolith of Motown and the recent buyouts of Chess and VeeJay—but a keen ear for talent has kept Brunswick competitive. All across the country ‘”Oh, Girl,” the latest hit by their biggest stars, the Chi-Lites, is in heavy rotation. The song is a doleful ballad about a man who thought that the best way to win affection was to behave how others wanted him to behave, but by doing so loses not only his lover but himself. It could be a metaphor for any activity whose primary motivation is the approval of others, and the crises that set in when that approval invariable wanes. It is a song about the perils of peer pressure.

In an apartment on the other side of town an old man pauses, puts down his pencil, and fiddles with one of the two knobs on the little plastic radio half-buried on his kitchen table. The man, Henry Darger, smiles. Not because it’s the fourth time he’s heard the song today, nor because the song is about girls, a subject with which he is more than a little obsessed. He smiles because a certain section of the lyrics keeps sticking in his mind: “So I tried to be hip, and think like the crowd / but not even the crowd can help me know. Oh girl, tell me, what am I gonna do?” Having worked alone for almost 50 years on a 15,000 page novel, hand illustrated with hundreds of pencil and ink drawings, he has no idea what that dilemma would be like.

Perhaps by now you have heard about Henry Darger, the orphaned hospital janitor who died in 1973 and whose exhibition of drawings at the Museum of American Folk was the most delightful show in New York this past year. Not because the drawings are freaky, or cool, or weird, or “pure,” or even topical, but because they are so sublime as to defy description. Even though it is obvious that the story has informed the making of his images, you don’t really need to know what the story is, because their beauty is enough, enough.

The drawings—epic, mural-sized watercolors and collages detailing the carnage, flight, retaliation and refuge of an army of pre-pubescent women known as the Vivian Girls—are most noteworthy for their compositional grandeur and brooding color schemes. Imagine the Prussian Army and a majorette team engaged in hand-to-hand combat across a vast plain of chrysanthemums and cypress trees. In many scenes the girls, most of whom are naked and have penises, are kicking ass. This isn’t so weird—certainly no more sensational than passages in the Bible or the Brothers Grimm. (In fact, my favorite drawing in the show was a rather modest depiction of the Vivian Girls trying to escape by rolling themselves up in sections of carpet.) What is impressive in Darger’s work is his formal inventiveness, the extent to which he was able to turn his practical limitations into such sublime, operatic complexity, and how that accomplishment might skew our perceptions of recent art.

Unable to draw very well (or at least to his own liking), Darger traced much of his imagery from advertisements and coloring books, at first working from a kind of inventory of stenciled figures and body parts that he would mix and match according to scale. In later works, after he had discovered the process of photo-enlarging at his corner drugstore, mechanical reproduction becomes strikingly evident. Thus his images are not propped up by commentaries on authorship, nor are they defined by mere banal repetition: rather, they are flush with the opulent free enterprise of his own ruthless economy. One is always aware of Darger’s fundamental tools—a cloud shape, a certain sienna-colored pot of paint—but never so much that they get in the way. Clearly Darger contrived all the details of his images as quickly he could, not so he could rush to the corner gallery before Gary Grad School got there but so he could concentrate and languish on the pictures themselves. However lean his wallet or limited his skills, Darger spent his time and effort to the fullest.

This expenditure becomes all the more impressive when we realize that Darger was only doing it for himself. These days, economists can assess the virtues of art as aptly as historians and critics, and I suspect that the sheer sense of surplus in Darger’s drawings is what makes them so welcome now. Given his obviously destitute life and his apparent disinterest in any public recognition, it seems fitting that Adam Smith, ole Free Market himself, might have best accounted for Darger’s particular type of genius. ‘Every individual’ he wrote, ‘intends only his own gain. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.’ Darger provided us with a level of intensity few trained professionals can muster without ever requiring viewers to complete the meaning of his work. Insider, outsider or upside-downer, Darger’s greatness was his ability to be ignored.

Note

1. Marcel Broodthaers, ‘To be bien pensant . . . or not to be. To be blind,’ in Le Privelêge de l’Art, Oxford, Museum of Modern Art (April—June, 1975)

Every Man for Himself Henry Darger

0 notes

Text

The Art of Disappearing

Originally uploaded on Joe Scanlan’s website.

A beautiful thing happened over the summer: Ellsworth Kelly’s Sculpture For A Large Wall came to New York. Originally commissioned in 1957 and installed in the lobby of the Penn Central Transportation Building in Philadelphia, the work was on view at Matthew Marks Gallery for the month of June. Which is to say that, forty-one years after the fact, Sculpture For A Large Wall made its first appearance in the art world. But even though the twelve by sixty-five foot anodized aluminum mural covered the entire east wall of the gallery—and even though two benches were provided for getting a good, museum-style bead on it—there were still moments when I swore it wasn’t there.

Let me explain: Kelly’s early drawings are simple ink studies of light and shadow, object and reflection, density and disintegration. Abstracted into graphic shapes (cartooned, really), the arch of a bridge or a slanting ray of light become interchangeable with the water surface or window sash that frame them. In other words, the bridge and the light become confused with what they are not. Sculpture For A Large Wall is the same idea on a larger scale, comprised of 104 shield-sized aluminum shapes mounted out of kilter on horizontal rods. Some of the shapes are painted and others have a brushed finish, many with edges cut to match those of adjoining shapes, so that from certain views they appear to be fixed together and yet from other angles they pull apart. As light plays across and through these shapes the spaces between them are alternately made to congeal into solid matter and then vaporize into air—to appear and disappear. After a while these optical effects affected my nervous system and made me uncertain of my own edges, made me unsure of where my body stopped and my surroundings started, even when planted on an oak bench.

While I sat there disintegrating I was reminded of my favorite show from last summer: Henry Dreyfuss, Directing Design: The Industrial Designer and His Work, at the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum. Dreyfuss is the most prevalent American objectmaker of this century, and in that respect his work is both more invisible and more profound than that of better-known designers. While it is impossible at this point to consider the work of Frank Gehry or the Eameses without also having to take into account their personas, I guarantee that any American over the age of thirty has encountered hundreds of Dreyfuss objects without ever having given him a thought. This is not to say that Dreyfuss is somehow a more noble or pious designer, but to suggest that, like Kelly’s relation to the Abstract Expressionists, there’s more than one way to make an impression.

Having cut his teeth on the Modern movement and 20s Art Deco, Dreyfuss’ commission by the Bell Telephone System to re-design their standard phones forever etched his work into the American consciousness, from the wall-mounted 500 series chatted on by housewives to the desktop model Tipi Hedren used in The Birds (1963). Big Ben alarm clocks, Polaroid Land Cameras, Honeywell room thermostats, John Deere tractors—just about any image of the United States from 1940 to the present, in some measure, depicts Henry Dreyfuss. What was so impressive about his show was the unsettling feeling of having such mundane details from your life suddenly presented to you in a vitrine. Not the obvious icons, but details in the background of the memory of your parents’ living room that night you spilled a can of Coke on the new white shag. There . . . behind the recliner . . . was that a Dreyfuss thermostat? What with so many artists combing the streets in search of “the everyday,” the Dreyfuss show was an excellent opportunity to admire one of the people most responsible for what it looks like.

Perhaps more than any of his peers, Henry Dreyfuss knew what it meant to have one’s work go unnoticed. For him this was the pinnacle of success since, from the standpoint of both the client and the discriminating consumer, the better the design, the surer its immersion in the world. In contrast to the fine arts, which are bound by distinction and preservation, it is a particularly perverse aspect of designers like Henry Dreyfuss that the more we engage their objects the more invisible they become. Dreyfuss’ oeuvre demonstrates that the most impressive aspect of de sign as an art form is not that you can sit on it or dial it or wear it in the rain, but that by doing so with pleasure unwittingly over time, and object’s beauty and rightness are confirmed. Until that day comes when, on the very verge of disappearing, someone deems that the object is worth saving.

Despite having lived in the relative obscurity of a corporate lobby for 40 years, Sculpture For A Large Wall eluded both public defacement and committee destruction. (Kelly’s Seven Sculptural Screens in Brass, another commission for the same building, was not so fortunate.) And now that the new owners of the Penn Central Building have decided not to include the sculpture in their overall renovations—leading Marks and Kelly to buy it back—the work’s place is in flux. It’s status, however, is not. As with a Dreyfuss design, the most important aspect of Kelly’s piece is the fact that we have been made aware of it, and the extent to which that awareness alters our perception is the measure of the sculpture’s success as a work of art. Through its simple evanescence, Sculpture For a Large Wall turned the superficial notions of “appearances” into a structural questioning of all that is solid, making you forget about your own ephemera for a moment and almost wish that you could disappear.

0 notes

Text

Unbuilt Roads: Eight Days a Week

Originally uploaded on Joe Scanlan’s website.

In 1994, after several years of studying the history of calendars and their basis in the solar system, I designed a new calendar that was more “in tune” with my personal rhythms. Although it contained the same 365 days, the calendar was divided into fifteen months instead of twelve and sixty-one weeks instead of fifty-two, with six days in each week instead of seven. I have lived by this calendar for the past three years in combination with the standard one, occasionally adjusting those aspects of the new calendar that did not feel right. Consequently, the current 1997 version has eight days per week (instead of seven), and three weeks per month (instead of four). It still has fifteen months, with the extra ones coming between December and January, May and June, and August and September.

This calendar really suits me, and now I am interested in sharing it with other people, to see if it might also suit them. This is the part of the project that remains unrealized. Here’s why: the current seven-day week is based on the seven “planets” that are visible to the naked eye: the sun, the moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn. In order to have an eight-day week, we need to have another planet made visible in the heavens, to correspond to the extra day. This requires either constructing an artificial planet (a satellite) and placing it in orbit in our solar system; or somehow altering either Uranus, Neptune or Pluto so that one of them would be visible to the naked eye from earth. Perhaps a giant lens or mirror could be built on one of them, the reflection of which would distinguish the planet from the other stars in the sky. This would make the global introduction of the eight-day calendar much easier, since its celestial logic would be evident to anyone looking at the night sky.

In exchange for fabricating an artificial planet, or for altering an existing one, the new planet could be named after its sponsor. I think Nike Corporation should underwrite the project since, like Pluto and Uranus, its name is derived from a Greek god. Likewise, Nikeday would be the name of the extra day in the week. It would come between Friday and Saturday and would be a versatile day, a work and/or play day depending on whether you made it part of the week or the weekend.First published in Unbuilt Roads: 107 Unrealized Projects, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, ed. (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1997): 91–92.

Download Unbuilt Roads: “Eight Days a Week”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Making and Wasting Time, or: A Calendar For Self-Employed Agnostics Living in Seasonal Climates Who Follow Astrology

Originally uploaded to Joe Scanlan’s website.

“They always say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself.” –Andy Warhol

At different times in different parts of the world, there was and is great variety in the number of days in the week: calendars with four- (Central Africa), five-, six- (Soviet Union), seven- (Chaldean, now Hebrew and Christian), eight- (Tuscany) nine-, ten- (France and ancient Egypt), thirteen- (Aztec), nineteen- (Baha’i) and twenty-day (Mayan) weeks did and still do exist. As sociologist and rhythm scholar Eviatar Zerubavel has noted, calendars that are not based on astronomy or theism are usually constructed around a pragmatic local cycle, as in the market weeks of West Africa, or a divinatory rhythm, as in the fugue-like calendars of Java and Indonesia. The Javanese have weekly cycles of two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight and nine days going simultaneously, distinguishing their appropriate travel, market, and festival days by the synchronicity of the different cadences. West African communities have weeks with as many days as there are villages in the area, so that each village can host an exclusive market day each week. Their days do not have celestial or god-based names, but are named after each corresponding village; consequently, their names inform the community when and where to buy things on a given day as opposed to what god to worship or what planet is on the rise.

*

Like language, the social structure of time is given to us. And, like language, we take what we like (or can use) from the days and weeks and ignore (or alter) the rest. Why not tailor the calendar to suit your particular needs and then intercalate the dominant calendar so that corresponding dates are readily available? Why not a calendar that functions personally or colloquially with more relevance, resonance and subtlety?

Sigmund Freud: Another procedure operates more energetically and more thoroughly. It regards reality as the sole enemy and as the source of all suffering, with which it is impossible to live, so that one must break off all relations with it if one is to be in any way happy. The hermit turns his back on the world and will have no truck with it. But one can do more than that; one can try to recreate the world, to build up in its stead another world in which its most unfavorable features are eliminated and replaced by others that are in conformity with one’s wishes. But whoever, in desperate defiance, sets out upon this path to happiness will as a rule attain nothing. Reality is too strong for him. He becomes a madman, who for the most part finds no one to help him in carrying through his delusion. It is asserted, however, that each one of us behaves in some respect like a paranoiac, corrects some aspect of the world that is unbearable to him by the construction of a wish, and introduces this illusion into reality.

*

By adding three months to the year and then shortening all fifteen of them to twenty-four days each, the months become consistent in length and more integrated with the change of seasons, with the three new months—Emmanuel, Dorothy and Elizabeth—accentuating the arrival of the new year, the end of spring, and the end of summer. Their location within the calendar year also pushes the months we normally associate with winter, spring, summer, and fall more squarely into their respective seasons. New Year’s Week would be a five-day period (six days, or an entire week, during Leap Year) that reconciles the monthly cycle with the 365-day year, just as the Mayan xma kaba kin (days without names) or the Aztec nemontemi (“hollow” or “superfluous” days) reconciled their calendars with the duration of the earth’s orbit around the sun.

The twenty-four day month also switches easily to seven or eight-day weeks, should the need arise, with no change in the monthly or yearly cycle. A seven-day week aligns just as well with Dorothy or Elizabeth as it does with May or October: both have three days left over after an exact number of weeks have passed. Personally, an eight-day week would be preferable if I had a full-time job since it would give me three days off each week and the month would only be three weeks long. A cinch! For now, though, I don’t have a full-time job, so I’m learning how to structure my own time. This calendar is designed to help make that process last as long as possible.

Laura Mulvey: The alternative is the thrill that comes from leaving the past behind without rejecting it, transcending outworn or oppressive forms, or daring to break with normal pleasurable expectations in order to conceive a new language of desire.

*

My father has been self-employed for twenty-three years. On June 5, 1971, he resigned from his job as a heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration repairman with the Julian Speer Company and went into business for himself. Three years earlier, we had moved from a house on Main Street in Stoutsville to a house in the country that had a pond, a creek and two acres of woods with prolific apple and walnut trees. June 5, 1971 was also my sister Kathy’s sixth birthday. Dad took her with him to Columbus that day not only as a present to her, but also as a way of demonstrating to his employer what he was missing by having to make all those overnight service calls to Ripley, Portsmouth, and Gallipolis. I hated my sister for that, since I wanted to go to Columbus and be a symbol for my father; but, with seven sons and one daughter, he obviously felt she would convey more symbolism. I can appreciate that now, just as I can appreciate his wanting to have more control over how and where he spent his time.

Sources:

Nathan Bushwick, Understanding the Jewish Calendar.

Francis H. Colson, The Week.

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents.

John Lynch, editor, The Coffee Table Book of Astrology.

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema.”

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own.

Eviatar Zerubavel, The Seven-Day Circle: the History and Meaning of the Week.

First published in Optimism, Hirsch Farm Project (Northbrook, Illinois: Hirsch Foundation, 1994): 10–17.

Download Making and Wasting Time Or: A Calendar For Self-Employed Agnostics Living in Seasonal Climates Who Follow Astrology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back to Basics and Back Again: Dan Peterman

Originally uploaded to Joe Scanlan’s website.

It’s common knowledge that recycling has had a very limited effect on the imbalance between the production and consumption of natural resources. The idea that we can save the planet by managing our glass, newspapers and plastics in naïve, not only because those materials are a mere fraction of the problem but also because they have not been readily absorbed into primary manufacturing processes. In any case, the journey from the garbage bin and back again is only one of many orbits that materials go through after they cease to be bauxite, petroleum, or trees. Thus the real concern of the planet is not the dissipation of garbage but the management of materials in constant states of transformation, commodification, and motion—a fact that the recycling industry seems reluctant to admit.

As long as that is the case, Dan Peterman’s work will not be about recycling. True, over the last ten years he has worked extensively with aluminum cans, recycled plastics and flammable garbage, and if there is a flaw in his method it is his own blindness to how strictly coded these materials are for most people. To be fair, Peterman’s blindness is more accurately an extreme focus, a proximity and familiarity with waste materials that precludes the didacticism usually associated with recycling. For six years after graduate school Peterman worked as a bulk mover and sorter for a southside Chicago recycling company called The Resource Center, an experience that seems to have expanded his student interest in object making processes into a broader stream of material consciousness. Knee-deep in the flux of the city’s refuse, Peterman developed an ‘oceanic’ appreciation of its absurd scale, to use Robert Smithson’s term (via Freud) for the anxiety induced by any seemingly limitless or formless expanse.

Peterman’s projects thus far (and there are many) are the direct result of negotiating his relationship to this expanse. Sometimes he attempts to map or structure it; other times he takes samples, turning them into art. Peterman’s works do not function as conclusions of final objects but as a kind of freeze-frame of larger systems in constant motion, crude models for how materials and products have become as transient as information. They are rooted entirely in his material experience, but his sensitivity towards the life cycle of substances allows his artworks to question their less tangible traits: symbolic meanings, social functions and monetary values. While working towards a more congenerous definition of art, he resists the current distinctions between conventional, institutional, site-specific and public art, suggesting that these distinctions are created by the artwork’s reception. All his works are formulated as public propositions, but geared to different audiences and for different effects.

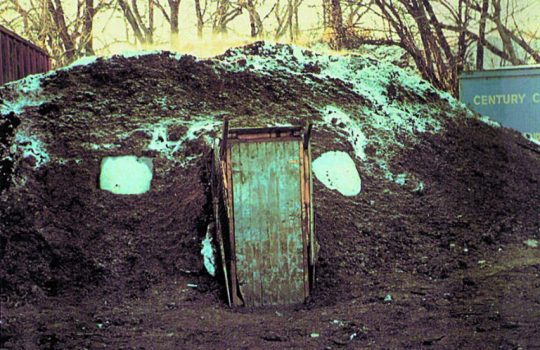

Chicago Compost Shelter (1988) marked a seminal development in Peterman’s conceptual sophistication and sense of humor. Winter being a particularly tough time for aluminum scavengers in Chicago, Peterman devised a temporary warming shelter at The Resource Center’s Seventy-First Street aluminum buy-back station. He began by constructing a wood canopy and door into the side of a defunct Volkswagen microbus; fashioned the interior with curtains, carpeting, blankets and a working radio; and then buried the entire vehicle in active compost, which gives off heat as a by-product of its chemical breakdown. (In addition to traditional recyclables, The Resource Center also composts a lot of the city of Chicago’s organic waste, much of which is horse manure generated by the division of mounted police.) The shelter maintained a 75-degree temperature throughout the winter, providing its audience with a reasonable place to warm up or spend the night.

The construction and intent of Compost Shelter grounded Peterman’s personal philosophy on his place in the wider scheme of things, as well as the extent to which he believed he could influence the status quo. Formally, the Compost Shelter was nearly identical to Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Wood Shed (1970). But where Smithson’s seminal work was structured around the idea of making entropy visible (dirt was piled onto the roof of a woodshed until the center beam cracked, at which point the activity was stopped), Compost Shelter’s confluence of materials was constructive, even hospitable—bringing a dilapidated van, organic waste and natural forces together in such a way that their traits complemented, rather than contradicted, each other. For Peterman—and for a lot of us—Smithson’s willful futility and fatalism have become a matter of course. And yet Peterman proposes that realistically reducing the potential of human influence doesn’t necessarily mean a diminution of agency, nor a lessening of the belief that change is still possible.

These shifts in scale and effectiveness are most evident in Peterman’s idea of what constitutes a natural resource. For him, bricks of aluminum cans and planks of reprocessed milk cartons are no less raw materials than timber or coal. Peterman’s lack of distinction between consumer waste and natural resources shifts his concept of nature away from its classical definition towards “all the stuff that nobody else wants.” Basically, a natural resource becomes anything that is accessible or affordable, regardless of how much it has been pre-processed or post-consumed. Nature is no longer primordial, some pure place or thing to be protected, but a complex system of material weights and volumes to be stockpiled, traded, and used.

In 1993 Dan Peterman, Sonia Labouriau, Kirsten Mosher and Nancy Rubins were invited to do “outdoor” projects in the charred shell of the New York Kunsthalle, which had been devastated by fire just before its official opening. Peterman had already been experimenting with the sculptural possibilities of a plastic plank product made from milk jugs and marketed as an indestructible substitute for wood. Its primary uses have been outdoor furniture and walls for playgrounds, parks and golf courses. Amused by the irony of so many urban nature preserves deploying such a synthetic and brutally permanent material, Peterman purchased 3,600 lbs of it to construct a kind of petrochemical banquet table that was both a by-product of and a potential site for mass consumption. The table’s length also mimicked the material’s manufacturing process: discarded plastic is shredded, emulsified, compressed and then extruded faster than applications or markets can be found for it. In a limited way Peterman has done his bit by purchasing a personal allotment of recycled plastic planks from which he makes, and remakes, art. Invited to participate in a group show at John Gibson Gallery in New York this summer, Peterman shipped a portion of the Kunsthalle piece to the gallery, reconfiguring it into a patio with benches, the remainder staying at the Kunsthalle until another project beckons or some configuration of it is purchased as art. Meanwhile, the artist has a convenient stockpile of work, strategically maintaining a “presense” (or nuisance) in New York.

Peterman’s ongoing SO2Project began in the Aperto section of the 1993 Venice Biennale, where he exhibited six certificates through which anyone could grant him the power of attorney to purchase sulfur dioxide shares on their behalf. There were no takers, so Peterman purchased five shares at $250 each for himself at the most recent auction in April. He was the highest bidder, though his shares represent only 0.00005 percent of the total allotment sold. The top volume buyer was Allowance Holding Corporation, who purchased 90,000 shares at $150 apiece—89.3 percent of the allotment—which pretty much set the market price. Nonetheless, for $1,250 Dan Peterman purchased the right to place five tons of sulfur dioxide into roughly 30 cubic miles of the atmosphere.

Since then he has learned that the most effective way for coal-burning power plants to reduce SO2 emissions is to install ‘scrubbers’ in their chimneys, where limestone and water draw the most SO2 out of the coal smoke. The by-product of this process is gypsum, the main ingredient for manufacturing plasterboard and drywall. This incidental production of gypsum could end the mining of ‘natural’ gypsum, as corporations source the material from power companies instead of the hills of northern Minnesota. Drywall and electricity are important utilities for contemporary art galleries, and the versatility and economy of drywall technology played a major role in the proliferation of such archetypal spaces as white cubes, rehabbed industrial lofts, and corporate lobbies. Thus Peterman’s investment is not so much about making money on the futures market as it is about purchasing a volume of material that is obliquely linked to our experience of art, and then making these links more visible. Peterman’s SO2 allotment might be calculated into a commensurate amount of gypsum or lighting to be used in an installation; increased or decreased in terms of its monetary value as the market develops; or expanded exponentially in relation to its corollary atmospheric volume if allowable SO2 levels are reduced. Given the specific electric consumption or wall space of an art institution, Peterman might also enlist the institution itself in the SO2 market in order to transfer shares to their account, thereby indicating the scale of the institution’s waste production and consumption and its relation to culture and the environment—in other words, the marketplace.

It remains unclear whether the SO2 shares will be either a worthwhile investment or an effective control mechanism. It also remains unclear what the context of Peterman’s project is, what its audience or impact might be, or how any of his actions are being received—questions which he intends to frame more precisely in an installation at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art in November. For now he prefers this ambiguity, this confusion of intention and potential. This, of course, is the nature of the “free” marketplace. As the variables now stand, the gradual reduction of SO2 emissions over the next ten years will lead to either a huge surplus of gypsum, the proliferation of other power sources (most likely nuclear), or the eventual obsoletion of the SO2 futures market. Most likely, however, is that enough interested money will get involved to reduce emission levels to a certain degree, but never so far as to jeopardize the interests of business. A permanent level of managed pollution would be the result, not exactly a utopian outcome.

Peterman has clearly signed onto a system outside of his control, yet his actions as an artist don’t demonstrate a literal faith in telling stories or seizing control. Rather they operate as metaphors for what’s individually possible in the new world of managed air space and material ownership. The SO2 Project is not about playing commodities broker, but about the fact that gambling with such huge volumes—and consequences—is even possible. Is it conceivable to go shopping and have that activity ‘produce’ as many resources as it consumes? The question posed by the modest, visually deadpan, Sulfur Dioxide certificates is, do you want that to be the case? Will you have a choice? Either way, Peterman’s offer to purchase individual pieces of sky on our behalf is one of the most disturbingly pragmatic and poetic gestures of our time.

First published in frieze (Sept./Oct., 1994): 36-9

Download Back to Basics and Back Again: Dan Peterman

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vija Celmins, McKee Gallery, New York

Originally uploaded to Joe Scanlan’s website.

A few months back, an amateur astronomer named Yuki Hyakutake spotted an uncharted brightness low in the eastern sky. Intrigued, professional astronomers soon determined that what Mr. Hyakutake saw was an unknown comet, one that had probably not passed within the earth’s views in 10,000 years. Although Mesolithic people in the middle and far east did not become skilled in astronomy for another 2,000 years, it is possible that they noticed the comet—perhaps even “enjoyed” it after a hard day of food-gathering and domesticating the dog. However, unlike the orbits of the sun, moon and five planets that eventually symbolized the Mesopotamian week, the comet’s disappearance probably thwarted any names or rituals that might have been attributed to the comet. So, for now at least, it is known as the comet Hyakutake.

A lot has happened since then, not the least of which is the development of the desire to drop what we’re doing for a few hours and in order to travel to darker, more remote regions to catch a glimpse of a fleeting asteroid. We seek out such phenomena because our daily lives do not often provide is with such vast beauty and coincidence, such sublime contentment and annihilation. Standing before a rare comet or the Grand Canyon, the mortal question “Why am I here?” gets massaged into a more beatific “What difference does it make?” When the answer to that question is “none,” or even “a little,” what harm is there in going on?

The work of Vija Celmins proposes that it is precisely the flawed, small-scale human redundancy of art that allows us to wrap our arms around the impoderable and commemorate the mundane. By depicting a desk lamp or a bowl of matzo ball soup in aggrandizing terms (i.e. oil on canvas) or rendering the minutiae of a desert floor in pencil, Celmins puts all human endeavor in its place, including her own. And yet, her fine draftsmanship also tends to elevate humanity a little, emphasizing the appropriateness of making things to the best of one’s abilities because one needs to; not as a way of mastering something, but as a way to coexist. These are pictures made for reasons beyond the express purpose of being looked at.

Celmins’ most recent show was comprised entirely of paintings and drawings of night skies. Most of them have comets streaking across their view and all of them are invented. She begins by making a blank charcoal ground and then erases the stars out of it, one by one. Some get worked into crisp points, others remain nebulous; some seem faint, far away, or dying, while others seem larger, closer, brighter. Unlike the scientific beauty of Renaissance drawings, in which the depiction of light falling on the surface of an object gives it not only form but priority in the natural order of things, Celmins’ drawings depict nothing but pure, emitted light. This is the captivation of starlight: it’s strong enough to reach our retinas but too weak to illuminate anything. Consequently it activates our brains without giving us anything to contemplate, save for our own stimulated circuitry and its pinpoint impetus, light years away. However recognizable these depictions are as images, it is their effect rather than their subject matter that compels us into them, collapsing time and space into the flatness of paper and the thickness of our heads. And in the space between our face and that surface: an abyss that is too familiar to be learned.

We are gently pulled back from this vortex when our eyes inevitable drift to the edges of Celmins’ drawings, where each image dissolves into the same smudgy ephemera that collects on the bottom of your shoes. The closer you look at these works the more likely they will push your attention back out into the room, remind you of the hand that made the image and of your body standing in space. Looking at them, a fugue-like balance is struck between pleasure and accuracy, between the effect of the image and the material that makes it up, between small wonder and smaller fact.

First published in frieze (June, July, August, 1996): 68–69.

Download Vija Celmins

0 notes

Text

Barry Le Va

First published in frieze (Nov./Dec., 1995): 68

Sonnabend, New York

I was strolling around New York in August, seeing what was up. I’d read that there was a Barry Le Va show at Sonnabend, but when I went there and pushed the elevator button for the third floor, it didn’t light up. A man in the elevator with me pushed five, and sure enough, the elevator skipped three and went straight to five. Sonnabend was closed. Riding back down, the elevator suddenly stopped on three and the doors opened. I got out and the doors closed behind me. Before venturing into the gallery, I pushed the call button to see if the elevator would come back—it would. I entered the silent, unlit space. Nobody there, no visible motion detectors, just numerous black and white forms on the floor. Daylight sliding down from the window gave the forms the air of an industrial park, or more precisely, the Amoco Oil Refinery outside Gary, Indiana. I fancied myself as Tony Smith on the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike, and settled in for a private, unauthorized ride.

However, a transcendental experience like Tony Smith’s isn’t possible with Le Va’s work, at least not in a beatific sense of religion, beauty or the open road. The kind of departure induced by Le Va’s work is more flat-footed and perplexing; a dry, buzzing, high-tension-wire kind of sensation caused by its persistent indeterminacy. It’s never clear whether a Le Va piece has been built up, or is some pared down a priori model; whether the model is molecular or galactic in scale; or whether there’s a model at all. We recognize something in his pieces—a glimmer of repetition, traces of physical and economic forces—that makes us believe it has a visible, definable source.

Walking around, I began to feel like Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas. After a while, I fell back on the idea that if I focused on individual elements (like a Minor White photograph) or stared at the overall group without focusing on anything (like a TV screen) the work would reveal itself. But this was just a crude way of approximating the viewing distance at which some sort of subject matter in my head would fit Le Va’s given arrangements—a sort of visual rolodexing, prolonged by the gallery’s emptiness. In other words, I was trying to get my buzz going. Some of the forms were grouped by likeness while others seemed to exert logical or gravitational influence on their surrounding forms, like chromosomes lining up just before a cell divides or fast food restaurants clustered around a freeway exit. All were about 18 inches high and cast of hydra-cal, latex and rubber; some were cylinders, some cubes, some longer rectilinear beams.

The forms were intrinsically black and white; the shadows they cast and the spaces between them contradicted and extended their volumes, further blurring the certainty of their edges and the arrangements as a whole—to the point where it was also unclear what direction they were going, whether they were cosmically coming together or entropically falling apart. Like screwing up your eyes in order to see the structural logic in Le Va’s work, you can screw up your time frame in order to carbon date its permanence. The duration of a gallery show is one thing; the duration of the pieces another; and the duration of rubber and calcium still another. Out of bounds and out of time, with no voices, no phones ringing, no access and little light, that seemed to be the point.

Download Barry Le Va

0 notes

Text

Death and Capitalism: The Countess Castiglione and Barbara Kruger

First published as “Shards In the Vanity Mirror,” at Eyestorm.com (December, 2000).

It is both an impressive achievement and an overdue banality that women artists currently enjoy unprecedented levels of success in art. From Rachel Whiteread to Elizabeth Peyton, Elke Kristyfek to Roni Horn, today’s woman artists are much less burdened by the stereotypes that constrained Anni Albers or Louise Bourgeois. Indeed, for today’s women artists, feminine stereotypes are more often an opportunity to be exploited than a mantel to be shed, to the extent that the qualifier “woman” no longer limits our appreciation of their standing as artists. This enlightened development has increased interest in those women whose pioneering works have helped to make it possible, and major exhibitions of the work of Valie Export, Anna Goncharova, Lee Krasner, Agnes Martin, Bridget Riley and Martha Rosler have occurred this year alone. Now Barbara Kruger, best known for her politically charged red and black photo montages, and the Countess de Castiglione, a politically ambitious noblewoman who made elaborate photo portraits of herself, can be added to the list.

At first glance, it would seem more reasonable to align Castiglione’s highly theatrical self portraits with the work of Cindy Sherman—the contemporary artist whose fictionalized photographs have turned the representation of women in art on its head. However, the simultaneous occasion of a show of Castiglione’s photographs at The Metropolitan Museum in New York with Barbara Kruger’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art makes for a more biting and unpredictable comparison, one that sharpens the pathos of Castiglione’s narcissism and dulls the bathos of Kruger’s diatribes.

Born Virginia Oldonini in 1837, The Countess Castiglione assumed her title through her marriage to the Count of Castiglione, Francesco Verasis, in 1854. The following year, in order to drum up support for the unification of Italy, King Vittorio Emanuele dispatched the Count and Countess to Paris where he hoped his wiles and her beauty would help garner the support of the French emperor Napoleon III. Little did King Vittorio know how persuasive the Countess’s beauty could be, when, only months after meeting Napoleon III, the Countess became part of an international scandal when she disappeared with him for several hours at a garden party. Not long after, the Countess made her first visit to the photo studio of Pierre-Louis Pierson. It is still not known whether the 400+ photographs they produced together over the next forty years were intended as personal trophies or illicit propoganda. Inspired by the heroines of literature and the stage as well as by the highest fashions of the day, Castiglione’s photographs were made for private viewers only or to satisfy her own colossal vanity. And even though most of her character references and costumes are now profoundly dated and illegible, over the years her faith in the power of appearances and her mastery of the tricks of the trade have helped turn her amateur obsessions into art.

Vengeance (1963-1967), for example, shows the Countess as the scowling Queen of Etruria, a fictional character apparently based on an obscure Spanish queen and the founding myths of the Roman Empire. Made in response to one of many marital bouts concerning her spending practices and scandalous behavior, the Countess commissioned the portrait and sent it to her husband with the note “to the Count of Castiglione from the Queen of Etruria.” (Nearly bankrupted by her extravagances, he eventually disowned her.) In a sweeter vein, Elvira (1861-67) shows the Countess seated in a ball gown of exceeding ridiculousness, with her bare head and shoulders visible above a mound of frothing silk, like a cherry perched on top of a ice cream sundae. Nonetheless, the stunning harmony of the stiff pose, the elaborate dress and her “la Lamballe” coiffure (layered pleats of hair piled high and dotted with pearls) is due in no small measure to the Countess’s ability to pull it off.

For all her deluded grandiosity, however, her most moving photographs were made in the final years of her life, when her failing beauty and bruised vanity led her to assume the self-imposed life of a hermit. Having moved to a small, barricaded apartment where mirrors were banned and which she had painted floor to ceiling black, the Countess nonetheless had the courage and self-awareness to memorialize her decline as works of art. The Foot, the Amputation of the Gruyère (1894) is the most self-deprecating from this period, showing a view of Castiglione’s feet as if she were lying in her own coffin. Similar in mood (but less macabre) are the St. Cecilia and the Rachel series, where the Countess assumed a number of veiled, langorous attitudes depicting melancholy and mourning. At one time supposedly having had a hand in the Unification of Italy and the Franco-Prussian War, the death of the Countess of Castiglione only confirmed her status as a first-rate femme fatale, one whose brash and elegant sexual politics live on in her images today.

Depictions of women as the victims of their own vanity or as the passive subjects of male desire are anathema to Barbara Kruger’s work, and I suspect she would loathe Castiglione’s self-abnegation regardless of her political conquests. Nonetheless, their goals are the same: to challenge and gain access to the masculine halls of power all the while demonstrating their independence from them. But where Castiglione gained her influence by sleeping with her allies, Kruger gains hers by sleeping with her enemies.

In our media-saturated world, where visual clichés and catch phrases get processed and reprocessed in a perpetual regurgitation of information, Barbara Kruger has accomplished no small feat: anytime you see red and white sans serif type pasted over a grainy black and white image, you immediately think of Barbara Kruger. Through her surgical reconfiguration of mainstream media images and words, Kruger has carved her idiosyncratic style out of the monolith of consumer capitalism, turning its soporific jingles into jagged slogans eviscerated by their over-sharpened hype. Kruger’s work is relentless, and her unflinching confidence over the years has been even more influential than her style, to the extent that you don’t really think of individual works by Barbara Kruger as much as you think of an overall philosophy and tone of voice. The tone of voice is aggressive, and the philosophy is attack!

Her retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York is an all out assault on the mind, an anti-aesthetic of fractured images and forked tongues spewing all the classic, acerbic Krugerisms: I Shop Therefor I Am. It’s A Small World, But Somebody Has to Clean It. Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face. Central to Kruger’s approach is her splintering of the apparent complicity of consumer society, a false contract that magazines and televsion suggest everyone is perfectly happy with. By turning the “we” of the mainstream media into “you and I” and “us and them,” Kruger demarcates a position for her work outside the male-dominated ramparts of Hollywood and Madison Avenue. At least that was the case in the 1980s, when such confrontational dissent still held a flicker of promise left over from the 1960s. Twenty years later, coming home to the same Madison Avenue she has railed against her whole career, Kruger’s guerilla warfare seems oddly heartwarming, even quaint, like Dadaist pranks nestled safely in vitrines or a wizened Johnny Lydon recounting the story of God Save The Queen.

Kruger’s work is better geared for the street, where it functions as pure information unencumbered by the material concerns of preservation and value. The sheer monetary value of art as property can overwhelm whatever message it might convey, and if Kruger’s method has a blind spot it is in regard to the fact that the economic forces responsible for the propagation and consumption of her work are largely beyond her control. An interesting irony, then, is that wherever Kruger has been willing to relinquish control to economic forces is precisely where her work is most interesting as art. The best part of her show at the Whitney is the final room of the exhibition, where her trademark cut-and-paste emblems are displayed on a numbing array of media and merchandise: T-shirts, ball caps, newspapers, TIME magazine covers, watches, mouse pads, paperweights . . . it goes on and on.

Thus, what for most other artists would be a populist nightmare for Kruger is the fullfilment of her wishes, the achievement of a powerful and independent voice embedded in the network that that voice sets out to critique. And although it could be argued that Kruger’s brand of mainstream defiance has become a cliché in itself, Kruger earns my respect for being able to accept her death by capitalism with the same aplomb that the Countess of Castiglione accepted hers: with dignity, a little irony, and a cold hard stare into the maw of her all-consuming adversary. That willingness attests not only to Kruger’s personal strength but also to the place she occupies for women artists. Like the dynamite that disappears as it blows a hole in a barrier, Kruger has sacrificed herself so that others may rush in.

Download Death and Capitalism: The Countess Castiglione and Barbara Kruger

0 notes

Text

First Action Heroes: The 100th Anniversary of Cinema

First published in frieze (Sept./Oct., 1995): 37-8.

On cue, a mustached man carefully opens the double doors of a factory in Lyon, France. The factory’s employees—mostly women in wide skirts and elaborate hats, but also men in dark full-length aprons and several bicycle riders—pour into the sunlight and disperse to the right and left, their shadows trailing under them in what appears to be the midday sun. A rambunctious dog topples the first cyclist, and several of the men gaze furtively in our direction as they come out, before lowering their heads and moving on. The next bicycles are better choreographed: half-way into the action a front tire noses out of a smaller door on the left and hangs there for several seconds, until two more bicycles appear in the double doorway. Then, like jets in formation, the first cyclist veers left, the second comes straight out and the third follows before turning right. As the last few people file out, one more bicycle appears, wobbles for a second in the bright sun, and pedals off. The man who opened the doors begins to close them again but he flickers, falters, can’t—Auguste and Louis Lumière, entrepreneurs and the sons of a wealthy photo-materials manufacturer, are out of film.

So goes La sortie des ouvriers de l’usine Lumière (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory), the first film by the brothers Lumière, made 100 years ago last March. Shot with a ‘cinématographe,’ the 16-pound, hand-cranked wooden box from which all of cinema derives its name, La sortie… and the machine that made it are fundamentally no different from the cameras and projectors used for Batman Forever or Waterworld. What is cinema but a string of transparent photographs spooled across an illuminated bicycle? This is the kind of simplicity that the Lumières loved (and Hollywood would like to forget), a charm that increased considerably when they took their apparatus home.

There, with the help of family and friends, the limitations of the cinématographe were more than offset by what John Grierson has described as a “fine careless rapture.” How fascinated we can be with a new machine! Everything seems different through it, and the Lumières—like us—filmed everything: the cat eating lunch, the baby walking, snowball fights, garden hose pranks, sack races, baby parades, the destruction of a wall. From the beginning, the most mundane activity was made to shimmer in the luminosity of their clear, silent material. For example, in La bataille de neige, friends and family members have been set up on opposing sides of a road to begin a furious snowball fight. In their haste to perform they sometimes fail to pack their projectiles properly, and end up hurling what disintegrating gossamers and comets at each other. When they do hit their dark targets the snowballs explode like white stars. At one point the obligatory cyclist enters the fray and is pelted to the ground by both sides, before gathering his equipment and getting away.

Bolstered by the success of their invention at home in Lyon and foreseeing its great albeit short-lived market potential (the brothers thought the cinématographe would be a fad, and against the protestation of their many later admirers, insisted that they were always businessmen and never artists), the Lumières went abroad. Filming people who were neither friends nor employees, however, proved a much more beguiling task. Apparently, in operation the cinématographe was as curious to look at as it was immobile, and most of the Lumières attempts at documenting everyday street life ended up recording their machine’s extraordinary public reception. In response, Auguste and Louis developed a film director’s two most useful skills: martial discipline and flattery.The Lumières spent a lot of energy getting their subjects to co-operate, to do what they would “normally do” rather than what they usually did, which was either to stare at the giant coffee mill being aimed at them or politely get out of the way. Neither reaction was satisfactory, so the Lumières steered people into Londres, l’entrée du cinématographe, steered them out of Dublin, l’incendie, or simply filmed the void caused by the camera itself, as in Moscow, le promenade.

The invention of the 20th century’s dominant art form aside, the most ingenious aspect of the first cinématographe was that it functioned as camera, developer and projector all in one, allowing the Lumières to make films as far away as Tokyo or Chicago and screen them in the same city days later. The device was so well-received at its debut in New York City that Felix Mesguich, the projectionist at the screening who had come on the Lumières behalf, was brought onstage afterwards amidst a standing ovation while the orchestra played La Marseillaise!

Originally intended to depict employees leaving work, La sortie… also documents the workers at the Lumière factory entering their leisure time, a relatively new spatial concept in the Spring of 1895. Inadvertently, then, the film captures them entering the arena of their lives in which film will become the most powerful influence. Thus, La sortie… foreshadows the availability of cinemas future consumers whilst acknowledging the midwives of its birth. 100 years later, the film functions as a kind of work/leisure conundrum for the 20th century, a tight emblem for the production/consumption spiral that threatens both to kill its parents and eat its young. A century on, bored by our machines and fed-up with the social contract, with Newt Gingrich the most powerful man in America and Quentin Tarantino topping the charts, it appears the killing and eating will soon begin.

Download First Action Heroes: The 100th Anniversary of Cinema

0 notes

Text

Last Action Hero

First published in frieze (summer, 1995): 7.–A. Finkl & Sons, Chicago

How does a steel mill attain cult status? In Chicago, where 100,000 manufacturing jobs have disappeared since 1970, companies who still actually make things have been given sanctuary in “Planned Manufacturing Districts.” In one such district, the North Branch Industrial Corridor, A. Finkl & Sons’ steel mill has become part cutting-edge manufacturer and part amusement park attraction, an ongoing, theatrical revival of Chicago’s past. Family owned and operated on the same site since 1870, Finkl’s may hold over 100 U.S. patents, but as steel mills go, it is so small and specialized as to be quaint. Their specialty is the Vacuum Arc De-gassing Process, a way of making steel in a virtual vacuum pressurized to 1/15,000 of normal air pressure and heated to 2,800º Fahrenheit. The furnace allows molten steel to be held at perfect teeming temperature while its chemistry is adjusted, its impurities being literally sucked out by the vacuum process.

In recent years Finkl’s has found itself amidst the gentrification of nearby Clybourn Avenue, now boasting as neighbors the Bossa Nova Restaurant (latin dinner and dancing); Whiskey River (country music and line dancing); Blockbuster Video (we have Forrest Gump!); Pet Care (50 lb. sacks of kitty litter); Kroch’s and Brentano’s (retail books); House of Teak (furniture and stuff); Pier One Imports (more stuff); Batter Up Arcade (restrooms for customers only); White Hen Pantry (24 hour ice cream and Oreos); Starbuck’s (today’s flavor: Guatemalan); and a Sony Octoplex (the same eight movies playing at the mall near you).

This story, of industry giving way to random shopping and miniature golf, could be told throughout America. What has distinguished Finkl’s is its willingness to bond with its consumer-oriented neighbors, simultaneously discovering—perhaps unwittingly—its own entertainment value. Finkl’s seems to have realized that the sheer novelty of its operation might benefit the company as much as the quality of its steel, and so, with the city’s blessing, the mill closed off one block of Southport Avenue, constructed ten meter-high steel archways at each end like and amusement park, and installed park benches, fir trees and seasonal flowers. The promenade was officially inaugurated with an open house and barbecue that included live music, A. Finkl & Sons merchandise, and the unveiling of a retired six-ton steamhammer and rotary saw asmonuments. Now after Die Hard III—Die Hard With a Vengeance lets out around midnight, and after the Riptide and the Blue Note close at 4 a.m., people go by Finkl’s to see if the melting room is open or if any ingots are aglow in the cooling yard.

Certainly the initial appeal of Finkl’s is that its melting room shares much with the chromatic range and machinery of action movies, the most appealing gimmick of the latter being human figures hurtling in slow motion from an exploding fire ball, their flailing bodies silhouetted against the bulging and expanding flames. The combination of passive inevitability (the body hurtling and falling to earth) and calculated success (the bomb has worked!) is compelling: you can identify with either or both. The melting room of Finkl’s provides a similar fantasy, involving the look of danger (molten steel) and awe of precision (finished steel). Seeing those colors and that scale relaxes us into our cinema mode. It’s cool, and entertaining, so we watch whether we know anything about steel manufacturing or not.

Finkl’s process also shares a kind of mystery with the production of action movies. Part of the appeal of such cinematic bomb blasts and elevator shaft rescues is the filmmakers’ ability to rehearse and edit these scenes to the point where they seem spontaneous. And just as Hollywood’s harnesses and stunt booms are invisible to us, so are Finkl’s controls. All we see through the vista of the melting room doors are silver-clad men against a cascade of molten metal and orange smoke, a scene which seems just as tantalizing as Backdraft or Terminator 2. The difference—and fascination—is that, however routine, Finkl Steel is spontaneous, and real.

Which is not to say that larger-than-life metal forging is heroic, merely that it is skilled. However visually stunning, steelmaking is most impressive when you are standing next to an orange-hot, coffin-sized cylinder of metal sizzling in the evening rain, its heat emanating through your clothes, its form made indistinct by the clash of the 1400º stainless steel and 40ª night air. Ultimately Finkl’s most profound attraction is that such obvious labor is utterly unfamiliar to we 100,000 artists, restaurant managers, and alternative rock bands who have replaced all those lost factory workers. To us, steelmaking seems no less contrived than a Civil War battle reenactment, no less anachronistic than colonial Williamsburg. For us, Finkl’s is as much theatre as it is manufacturing, a theme park based on the Modern era, one that, like the smithy at Williamsburg, Virginia, happens to sell what it turns out.

In the end, however, my fascination with A. Finkl & Sons isn’t of much use since, like heroism, it is the product of ignorance. De Tocqueville speculated that “if men were ever to content themselves with material objects, it is probable that they would lose by degrees the art of producing them; and they would enjoy them in the end like the brutes, without discernment and without improvement.” Fresh from the movies or the strip mall, with a copy of Red Desert on the front seat of the car and 50 points of kitty litter in the trunk, it makes no difference to me whether A. Finkl & Sons makes good steel or not.

Should it?

Download Last Action Hero

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Shock of the Used: The Relevance of Charles and Ray Eames

First published in frieze (Jan./Feb., 1996): 30-31

There is a common refrain in today’s art world that the public doesn’t care about art anymore—the sense being that rank and file viewers lack either the sensitivity to discern art, the knowledge to understand it, the ambition to decipher it or the attention span to be challenged by it. Museums, the segment most invested in the public’s art education, have responded by providing art appreciation classes, generous text panels, recorded headset tours, and retrospectives on Edward Hopper and Claude Monet. If generating interest in art made by anyone other than the great turnstile spinners is a challenge, then generating interest in anything made after 1960 is difficult indeed. And while the idea-based art of the 1960s is seen as the beginning of the period when art fans and flâneurs alike didn’t “get it,” the theory– and commodity-based art of the late 1980s is more often cited as the apex of the audience’s exasperation, the silver anniversary of their not getting it. The truth is to the contrary: the late 80s marked the moment when people began to get it all too well. Understanding the end of originality, the seamful, pernicious relationships between language and pictures and products and desires, the occasional need for art to be hypothetical, intangible, to become less precious and more democratic and to depict a wider range of subjects and types from the world—many fans of seminal culture left the galleries and museums to conduct their own cultural anthropology.

Which might just explain the recent, fanatical interest in the furniture of Charles and Ray Eames. If at one time or another it was important for American art to depict popular icons (Jasper Johns), for such icons to be mechanically reproducible (Andy Warhol) or appropriated (Richard Prince), for their authorship to be subverted (Sherrie Levine) and their status challenged (Mike Kelly); and if it was radically significant for the work of art to be industrially fabricated (Donald Judd), to be simultaneously sign and signified (Robert Gober), to be democratically distributed (Felix Gonzalez-Torres) or collaboratively produced (Katie Ericson and Mel Ziegler), then Charles and Ray Eames are among the most important artists of this century.