I'm Lala Rose. I'm Bi. 24. I'm a Feminist. I'm a Self-Proclaimed Goth. I'm also sarcastic as Fuck. I enjoy writing, drawing, (pretending to be) a Badass, watching movies... Fuck this sounds like a list. I treat the people of Tumblr like my friends. Which is...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

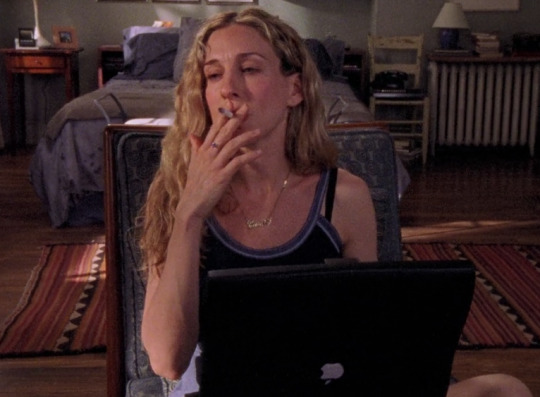

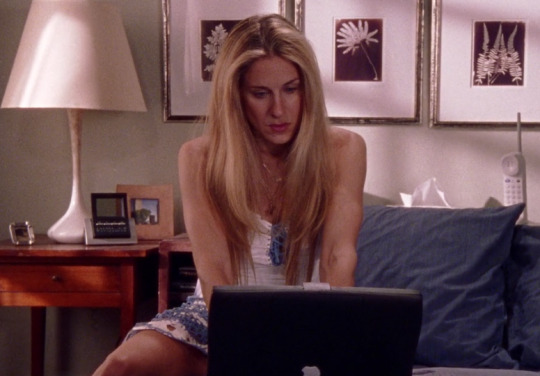

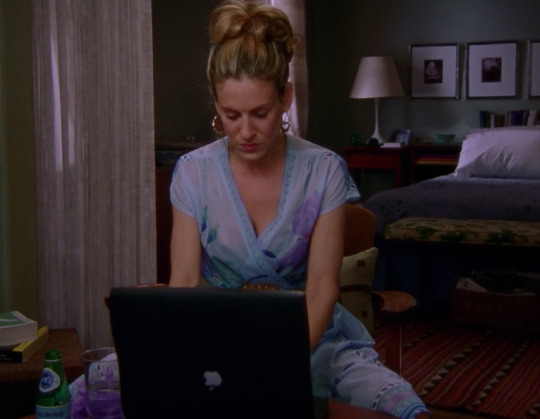

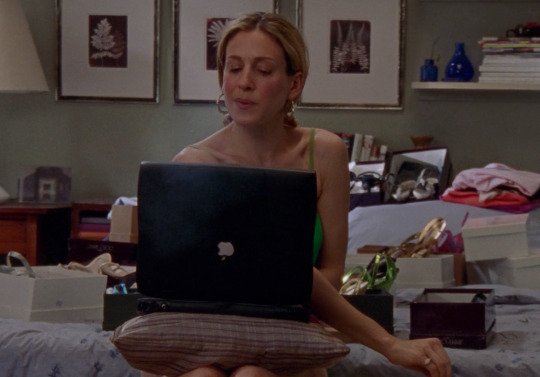

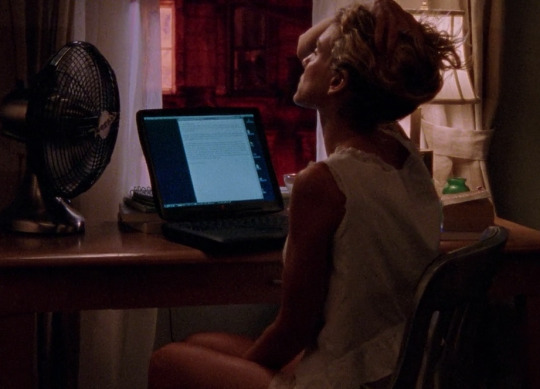

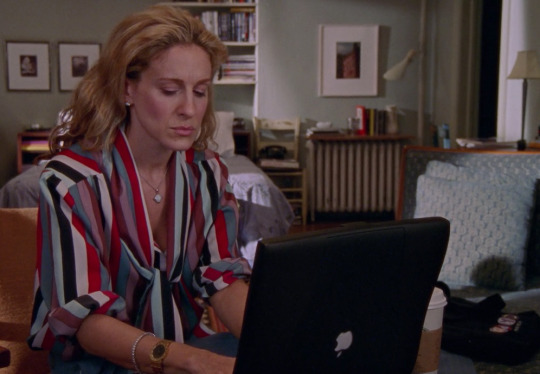

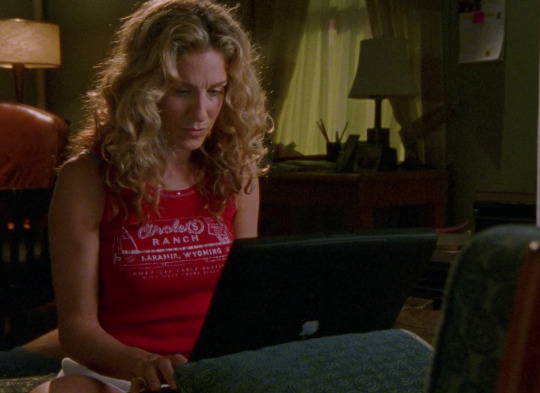

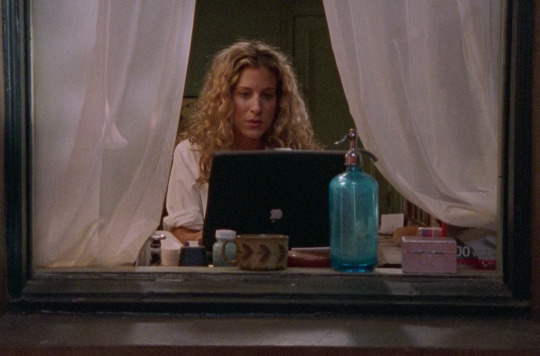

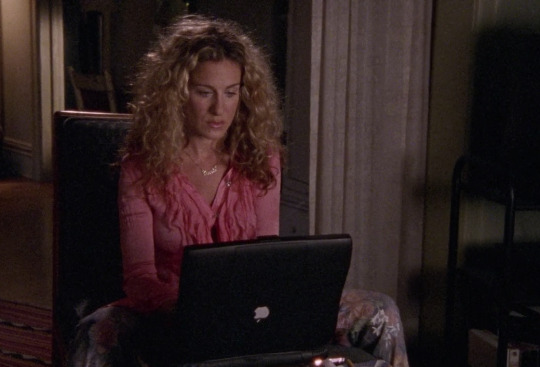

Carrie Bradshaw + writing, Sex and the City

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

charlotte york (my favorite lover girl)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

SEX AND THE CITY (1998-2004) 4.01: The Agony and the Ex-tacy

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

KRISTIN DAVIS as CHARLOTTE YORK in Sex and the City (1998 — 2004)

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

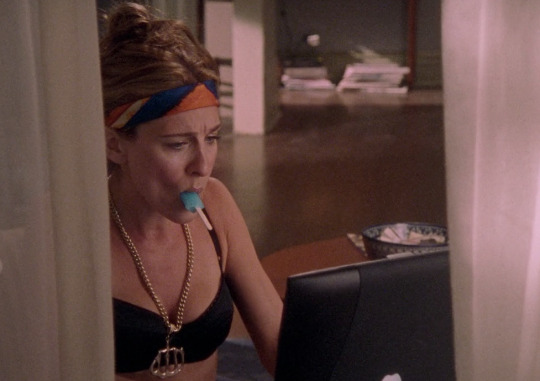

SEX AND THE CITY (1998-2004)

3.07 | “Drama Queens”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

CHARLOTTE YORK in Sex and the City S03E10 • “All or Nothing”

730 notes

·

View notes

Text

SEX AND THE CITY | 6.09 "A Woman's Right to Shoes"

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doechii at the Tom Ford Show, Paris Fashion Week 2025

510 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blindspotting | 2.02 - Life Is Too Short

61 notes

·

View notes