Calling on the international community to use the Day to raise awareness and intensify actions towards ending obstetric fistula, as well as urging post-surgery follow-up and tracking of fistula patients.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Women's rights are human rights! End fistula now!

The theme of the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula 2021 was Women's rights are human rights! End fistula now!

According to the UN, hundreds of thousands of women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Arab region, and Latin America and the Caribbean are living with obstetric fistula.

The average cost of treatment for obstetric fistula is $600. Treatment typically includes surgery, post-operative care, and rehabilitation support.

#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula#23 May#Walk against fistula#train fistula surgeons.#fistula surgeries#obstetric fistula#fistula

0 notes

Text

Addressing the fistula treatment gap and rising to the 2030 challenge.

Obstetric fistula is a neglected public health and human rights issue. It occurs almost exclusively in low-resource regions, resulting in permanent urinary and/or fecal incontinence. Although the exact prevalence remains unknown, it starkly outweighs the limited pool of skilled fistula surgeons needed to repair this childbirth injury. Several global movements have, however, enabled the international community to make major strides in recent decades.

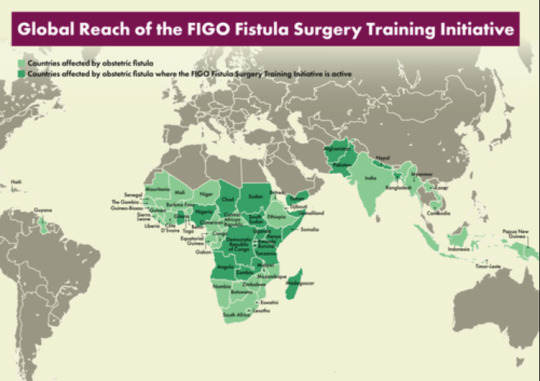

FIGO's Fistula Surgery Training Initiative, launched in 2012, has made significant gains in building the capacity of local fistula surgeons to steadily close the fistula treatment gap.

Training and education are delivered via FIGO and partners’ Global Competency-based Fistula Surgery Training Manual and tailored toward the needs and skill level of each trainee surgeon (FIGO Fellow).

There are currently 62 Fellows from 22 fistula-affected countries on the training program, who have collectively performed over 10 000 surgical repairs. The initiative also contributes to the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (1, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 17). The UN's ambitious target to end fistula by 2030 will be unobtainable unless sufficient resources are mobilized and affected countries are empowered to develop their own sustainable eradication plans, including access to safe delivery and emergency obstetric services.

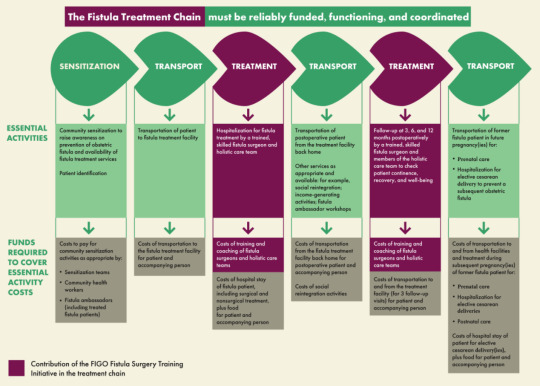

The fistula Treament chain must be reliably funded, functioning and coordinated.

#Fistula Surgery Training Initiative#fistula#23 May#sdg3#Sustainable Development Goal 3#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula#maternal and child health

0 notes

Text

Global need to strengthen financial support.

A major challenge facing countries is the insufficient level of national financial resources for promoting maternal health and addressing obstetric fistula. The problem is compounded further by low levels of official development assistance directed towards maternal and newborn health. Contributions to the Campaign to End Fistula are vastly insufficient to meet needs and have steadily declined in recent years. An urgent redoubling of efforts is required to keep fistula from being a neglected issue by intensifying resource mobilization in order to end fistula within a generation.

Efforts to end obstetric fistula are integrated into and supported by initiatives with a broader maternal health focus. These include the Every Woman, Every Child initiative and the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, the H6 Partnership, the Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and the Maternal Health Thematic Fund (MHTF) of UNFPA.

In 2014 and 2015, contributions to the Campaign to End Fistula included financial commitments from the Governments of Iceland, Luxembourg and Poland, private individuals, philanthropic foundations, such as Zonta International, and private corporations, including Johnson & Johnson, Total, Noble Energy, Virgin Unite, UNFCU Foundation and the MTN Foundation. In addition, private sector partners such as Johnson & Johnson provided funding for midwifery and the provision of skilled birth attendants, a key component of preventing obstetric fistula and ensuring women access medical services during childbirth.

Financial contributions and strategic activities for the prevention and treatment of fistula have thus far yielded positive results, but far more is needed to eliminate fistula worldwide. The number of fistula surgical repairs performed each year, for example, treats a very small percentage of the estimated number of existing and new cases, meaning that at current rates of surgery, the majority of women with fistula will die without ever receiving treatment. Partnerships must be strengthened and financial commitments significantly increased for all aspects of fistula prevention, treatment and support for survivors in order to end fistula within a generation while striving to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Bolster midwifery care, enhance access to family planning, train fistula surgeons.

In order to accelerate progress towards ending maternal and newborn mortality, road maps were established to help governments strengthen health systems and plan and mobilize support for skilled attendance during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period. With support from the United Nations and partners, 43 African countries initially developed road maps to accelerate the reduction in maternal mortality and included maternal, newborn and child health in their poverty reduction strategies and health plans. Of those countries, 35 developed operational plans for maternal and newborn health at the district level.

In 2015, a comprehensive five-year review of the status of implementation of the Maputo Plan of Action for the Operationalization of the Continental Policy Framework on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (2007-2010) was undertaken. The Plan of Action called for further strengthening the health sector and increasing resource allocations. While some progress has been made in implementing the Plan of Action, the corresponding allocation of resources remains very limited, with only a few countries having allocated funds for sexual and reproductive health services. Subsequently, two of the key continental policy frameworks were negotiated, for extensions to cover the period from 2016 to 2030, to address sexual and reproductive health, including as regards obstetric fistula. The Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa promotes intensified implementation of the Maputo Plan of Action.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), donors and civil society organizations provide support for the campaign at the national and regional levels. Numerous strategic policy dialogue and advocacy activities have been conducted since its launch. Nearly all countries in Africa have launched the Campaign at the national level.

In 2015, UNFPA and the Gender Development Centre of the Economic Community of West African States supported 15 countries in developing five-year action plans to end obstetric fistula. With a view to reducing maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity, strengthening midwifery and increasing the availability of midwives in West Africa, the Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend Project was launched in 2015 by the Governments of Burkina Faso, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Mauritania and the Niger, with support from UNFPA and the World Bank.

East and Southern Africa reduced its maternal mortality ratio from 918 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 407 per 100,000 in 2015, a 56 per cent reduction. The greatest improvements were observed in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Rwanda. Eritrea, Ethiopia and Uganda are among the countries in Africa with the most established programmes for addressing fistula and have national strategies and programmes of action to eliminate fistula in the next few years. In Djibouti, Somalia, the Sudan and Yemen, fistula is addressed through both humanitarian and development programmes, as it is more prevalent in conflictaffected areas owing to the lack of access to emergency obstetric care. As a result of the ongoing conflict in Yemen, the programme to address fistula had to be suspended, with refugees fleeing to Djibouti. In response, UNFPA, along with partners, started a project to decentralize emergency obstetric and newborn care services to the district hospital of the northern region of Djibouti, in order to prevent fistula. For the first time, Caesarean sections are being performed in rural areas outside the capital city. In addition, general practitioners are currently being trained to perform emergency obstetric and newborn care, including Caesarean sections.

In the Asia and Pacific region, obstetric fistula continues to be a significant cause of morbidity, suffering and social isolation for girls and women, in particular in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan, where a large gap persists in the provision of health and social services in rural areas. Multiple partners have launched country-specific campaigns to end fistula. In Afghanistan there is a focus on raising community awareness and developing a manual for surgical management of fistula, and Pakistan has launched a multi-level effort to bolster midwifery care, enhance access to family planning, train fistula surgeons. Centres of excellence for fistula surgery, which serve as referral centres, have been established in Bangladesh and Nepal, while midwifery education is being strengthened. In Nepal, the Government’s intervention in fistula care is supported by UNFPA, the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics and the Women’s Rehabilitation Centre.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, Haiti has recently taken action to better understand and address the problem of fistula in the country. In 2016, the Government of Haiti and UNFPA commemorated the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula with a panel of experts including the Haitian Society of Urology, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Haiti, Partners in Health, the Haitian Midwifery Association and the Institut National Supérieur de Formation de Sages-femmes, resulting in a commitment to formulate a national plan for ending fistula.

South-South cooperation is an essential part of the strategy for ending obstetric fistula. In order to build national capacity and sustainability and increase access to fistula treatment in francophone and lusophone countries (which at times struggle to secure technical assistance in their native language), expert fistula surgeons from Chad, Mozambique and Senegal have supported training and treatment in countries including Angola, Burundi and Guinea-Bissau in recent years. Several countries in Africa, including Chad, the Niger and Togo supported the participation of national midwifery association members in the first congress of the Federation of Midwives’ Associations of Francophone Africa, held in Bamako, in October 2015.

#strengthen health systems#increase resource allocations#sexual and reproductive health services#bolster midwifery care#enhance access to family planning#train fistula surgeons.#United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)#midwifery education

0 notes

Text

Initiatives taken at the international, regional and national levels to end Fistula.

In 2007, at its sixty-second session, the General Assembly acknowledged obstetric fistula as a major women’s health issue for the first time and adopted resolution 62/138 on supporting efforts to eliminate obstetric fistula, which was sponsored by a large number of Member States. Subsequently, in 2010, 2012 and 2014, at its sixty-fifth, sixty-seventh and sixty-ninth sessions, the Assembly adopted resolutions 65/188, 67/147 and 69/148, respectively, in which it called for a renewed focus on and intensified efforts for eliminating obstetric fistula. With each resolution, States reaffirmed their obligation to promote and protect the rights of all women and girls and to contribute to efforts to end fistula, including the global Campaign to End Fistula.

In September 2015, world leaders gathered at the United Nations in New York and unanimously adopted a set of global goals on eliminating poverty, achieving gender equality and securing health and well-being for all people. The bold new universal agenda outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by the General Assembly in it resolution 70/1. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals build on the success of the Millennium Development Goals and outline commitments to achieve those which were not realized, including Goal 5 of the Millennium Development Goals on improving maternal health. The full and effective implementation and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals will be essential to ending obstetric fistula.

In the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Popula tion and Development, adopted in Cairo in 1994, and the outcome documents of the review conferences thereon, maternal health was recognized as a key component of sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. In his report on the framework of actions for the follow-up to the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development beyond 2014, the Secretary-General underscored that obstetric fistula “represents the face of failure as a global community to protect the sexual and reproductive health of women and girls”. At the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995, the Platform for Action was adopted, with a call for global efforts to improve women’s health, including their sexual and reproductive health. In the political declaration adopted by the Commission on the Status of Women at its fifty-ninth session, the importance of women’s health was further underscored as part of the review and appraisal of the implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action . In 2015, the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health was revised to take a more comprehensive approach that aims to keep women, children and adolescents at the heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, unlocking their vast potential for transformative change. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016-2030) takes a life-course approach to attaining the highest standards of health and well-being, physical, mental and social, at every age. It aims to end preventable maternal and newborn mortality, reduce the rate of global maternal mortality to less than 70 women per 100,000 live births (Goal 3, target 3.1) and support countries in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. At the sixty-ninth World Health Assembly, Member States were invited to commit to implementing the strategy, along with the accompanying operational plan to take it forward (see World Health Assembly resolution 69.2 of 28 May 2016). The resolution placed strong emphasis on country leadership and highlighted the need to strengthen accountability through monitoring national progress and strengthening capacity to collect, analyse and use data. It underscored the importance of developing a sustainable evidence-informed health financing strategy, strengthening health systems and building partnerships with a wide range of actors across different sectors.

On 26 May 2015, the World Health Assembly, at its sixty-eighth session, unanimously adopted resolution 68.15 on strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anaesthesia as a component of universal health coverage, which calls for access to emergency and essential surgery for all, including to prevent and treat obstetric fistula.

As part of commemorations of the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula in 2016, the Secretary-General called for an end to fistula within a generation. The call was announced at the global level during the fourth global Women Deliver Conference, held in Copenhagen, from 16 to 19 May 2016.

0 notes

Text

Major national initiatives

Countries are making progress in reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. The global maternal mortality ratio decreased by 44 per cent from 1990 to 2015 and the number of maternal deaths has fallen, over the same period, from 532,000 per year to 303,000.10 Notwithstanding the remarkable gains made in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality and in improving reproductive health, major challenges remain and must be addressed. Improving sexual and reproductive health must be a country-owned and country-driven process. Countries need to allocate a greater proportion of their national budgets to health, with additional technical and financial support provided by the international community. According to data being collected by UNFPA, at present, at least 15 countries affected by fistula have national strategies for eliminating obstetric fistula, and nine of those countries have costed, time -bound operational plans. Additionally, at least 28 countries have national obstetric fistula task forces, which serve as a coordinating mechanism in-country for partner activities.

Several countries employ innovative approaches to raise awareness and increase access to treatment. Telephone hotlines continue to provide information about fistula treatment in Burundi (in partnership with Médecins sans frontières), Cambodia, Kenya, Malawi and Sierra Leone, using mobile phones to connect women living in remote locations to medical care. In the United Republic of Tanzania, the mobile phone-based money transfer microfinancing service known as M-PESA, established in 2009, continues to cover the upfront transportation costs of impoverished fistula patients, so they can access fistula surgery. That system, along with those sponsored by Freedom from Fistula Foundation in Malawi and Sierra Leone, also provide free accommodation and meals before and after surgery, thereby addressing major barriers to accessing fistula treatment. In Malawi, fistula ambassadors, former patients who have undergone training in community awareness of fistula, are now also patient recruiters, escorting new patients to the Fistula Care Centre in Lilongwe for treatment and speaking to rural communities about how to prevent fistula and access care. Many initiatives are under way for improved data collection to track patient outcome and improve surgical practice. Despite the ongoing humanitarian situation, fistula task forces were established in all three zones of Somalia in 2015, addressing the prevention and treatment of fistula through family planning, delivery and post-delivery care, including maternity waiting homes, providing ambulances, and awareness-raising campaigns through the media and goodwill ambassadors for the Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa. With the support of UNFPA, enhanced service delivery contributed to increased rates of skilled attendance at birth, expanded and improved midwifery education and workforce policies and strengthened midwifery associations.

In 2015, Bangladesh disseminated its strategy to address fistula, in collaboration with EngenderHealth and UNFPA, which includes a costed plan with multiple approaches to tackling fistula in the country. The Government acknowledged the status of midwifery as a profession in 2016 and announced the creation of 3,000 midwifery posts, as only 42 per cent of births are currently attended by skilled providers. To date, 10 medical colleges are being supported in providing fistula repair services, while complicated cases are referred to the national fistula centre. Approximately 250 doctors and 280 nurses have been trained on surgery and management of fistula and at the national level, 5,000 patients have had fistula repair surgery. In 2016, Bangladesh plans to conduct a national study of maternal mortality and morbidity, which will include estimating the national prevalence of obstetric fistula.

In 2015, the Government of Togo, UNFPA and civil society partners launched a socioeconomic reintegration campaign for fistula survivors. Following surgery to repair their fistula, women were offered training and start-up funding towards their chosen profession. A similar rehabilitation programme in Chad has supported 2,000 women since 2007. The programme also educates health-care workers and midwives uses media to spread the message that obstetric fistula is a major risk associated with giving birth as a teenager.

Healing Hands of Joy operates a safe motherhood ambassador training and reintegration programme in Ethiopia for women who have received treatment for fistula. In 2015, the organization opened two new centres in Bahir Dar and Hawassa, in addition to their previously established centre in Mekelle. The centres trained 524 ambassadors between 2010 and 2015, and they in turn have educated an estimated 13,720 pregnant women, contributed to 12,171 safe institutional deliveries and identified 80 cases of fistula during that period. They have also provided 115 microloans to fistula survivors to support income-generating activities. The organization partners with others, including Hamlin Fistula Ethiopia and Pathfinder International, to ensure all aspects of fistula prevention, treatment and support for survivors are addressed.

In the Sudan, the national health sector strategy has strengthened the provision of emergency obstetric and newborn care by upgrading and/or equipping health-care facilities, training midwives and health-care providers, supporting the referral system for complicated deliveries and training doctors from rural areas at the national fistula centre in Khartoum. The federal Ministry of Health agreed to establish a national fistula task force, under its own leadership, for implementing the fistula national work plan and mobilizing funds, including establishing an association of fistula surgeons in Sudan.

In 2015, Pakistan launched a campaign to end obstetric fistula, including by establishing a national and six regional fistula centres to provide free fistula surgical repairs. More than 4,300 fistula patients have had fistula repair surgery and 600 women and girls have been rehabilitated. Seven surgeons have been trained on surgical techniques while, in addition, approximately 650 doctors have been trained on fistula prevention and management. The national midwifery degree programme was introduced in 2013 with a curriculum based on the International Confederation of Midwives and WHO competencies. In addition, the Government is revitalizing the family planning role of women health-care workers to enable greater access to and use of modern contraceptives and advocate healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies.

Tragically, the outbreak of Ebola virus disease severely threatened and worsened maternal and newborn survival and health in the affected countries. Nevertheless, countries affected by Ebola in 2014 and 2015 made significant efforts to continue work to prevent and repair obstetric fistulas. Liberia channelled much of its resources and activities in directly responding to the outbreak and put some regular activities on hold. Nevertheless, with the support of organizations including Zonta International and UNFPA, some services to fistula survivors continued to be provided. In Sierra Leone, while maternity care continued at the Aberdeen Wome n’s Centre, fistula surgeries were temporarily paused, but resumed immediately once the country was declared Ebola-free.

0 notes

Text

Implement a competency-based fistula surgery training programme to expand global treatment capacity.

While global progress is being made to increase access to fistula treatment for women and girls in need, it is vastly insufficient. In 2015, more than 13,000 fistula surgeries were directly supported by UNFPA, a significant increase from 10,000 surgeries in 2013. Several countries affected by fistula have increased the number of surgeries performed in recent years, including Madagascar, which reported an increase in surgeries from 245 in 2013 to 829 in 2015. Still, only a fraction of those in need of treatment actually receive it.

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, the International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons and the Fistula Foundation continue to implement a competency-based fistula surgery training programme to expand global treatment capacity. A dramatic and sustainable scaling-up of quality treatment services and in the number of trained competent fistula surgeons are needed. Addressing the unmet need for fistula surgical repair should be a high priority of the sustainable development agenda.

The International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons and UNFPA developed fistula repair kits that have the necessary supplies to perform fistula repair surgery, thereby promoting increased access to quality fistula treatment and care. Through a partnership with Johnson & Johnson, high-quality sutures were integrated into the kits in 2015, which reduced the cost of an individual kit by 39 per cent. In 2015, UNFPA procured more than 550 of the kits for use at health-care facilities.

A project led by EngenderHealth and supported by the United States Agency for International Development, known as “The Fistula Care Plus Project”, expands access to fistula services and builds the evidence base for ending fistula. From 2005 to March 2016, EngenderHealth supported over 33,400 surgical fistula repairs.

To build sustainable fistula repair capacity, over 1,700 health-facility personnel in clinical fistula care, including 33 fistula surgeons, have been trained through the project. The project has also built a global database to monitor and manage fistula programme data using a health management information system, a platform that has been adopted by over 40 national governments. In addition, WHO and Engender Health collaborated in conducting a study to improve the efficiency and cost effectiveness of health systems and the post-surgery recovery of fistula patients for their overall health and well-being.

The lack of awareness that treatment for fistula is possible and available and the high cost of accessing that treatment constitute major barriers to caring for women and girls suffering from fistula. Countries should make every effort to make fistula services accessible to all who need them, including through the provision, in strategically selected hospitals, of integrated fistula services that are available continuously and provide the full continuum of holistic care and support for the treatment, rehabilitation and vital follow-up of fistula survivors

#International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)#United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)#World Health Organization (WHO)#fistula surgeries#Fistula Patients#EngenderHealth

0 notes

Text

Emphasizing the crucial role of midwives to reduce the high number of preventable maternal deaths and disabilities.

Obstetric fistula is an outcome of socioeconomic and gender inequalities and the failure of health-care systems to provide accessible, equitable, high-quality maternal health care, including skilled attendance during childbirth, emergency obstetric care in case of complications and family planning. Over the past two years, considerable progress has been made in focusing attention on maternal deaths and disabilities, including obstetric fistula. Despite the positive developments, manyserious challenges remain. It is a human rights violation that, in the twenty-first century, the poorest, most vulnerable women and girls suffer needlessly from this devastating condition, which has been virtually eliminated in much of the world. It is imperative that the international community act urgently to end preventable maternal mortality and morbidity, including through developing a global action plan to end fistula within a generation, as part of integrated efforts to strengthen health systems, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health services and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Significantly intensified political commitment and greater financial mobilization are urgently needed to accelerate progress towards eliminating this global scourge, preventing all new cases and treating all existing cases. There is an urgent and ongoing need for committed, multi-year, national and international cooperation and partnership (both public and private) to provide the resources necessary to reach all women and girls suffering from this condition and to ensure sufficient, sustainable and continued elimination efforts. Special attention should be paid to intensifying the provision of support to countries with the highest maternal mortality and morbidity levels. This will enable such countries to provide free access to fistula treatment services, given that most fistula survivors are poor and cannot afford the cost of treatment.

Accelerated efforts are critically needed to improve the health of women and girls globally, with an increased focus on social determinants that affect their wellbeing. These include the provision of universal education for women and girls, economic empowerment with access to microcredit and microfinancing, legal reforms and social initiatives to protect women and girls from violence and discrimination, ending child marriage and early pregnancy, and the promotion and protection of their human rights. This will ensure their safety and well-being, their empowerment and ability to contribute to their families and their communities.

It is essential that universal access to sexual and reproductive health services, as called for in the Sustainable Development Goals, be integrated into planning processes at the national, regional and international levels in order to end obstetric fistula. There is a global consensus on the key interventions necessary to reduce maternal deaths and disabilities and an urgent need to scale up the three wellknown, cost-effective interventions (skilled birth attendance, emergency obstetric and newborn care and family planning), emphasizing the crucial role of midwives to reduce the high number of preventable maternal deaths and disabilities, including those resulting from obstetric fistula.

The following specific, critical actions, with a human rights-based approach, must be taken urgently by Member States and the international community, including in partnership with the private sector, to end obstetric fistula within a generation and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Prevention and treatment strategies and interventions.

(a) Committing greater investment to strengthening health-care systems, ensuring well-trained, skilled medical personnel, especially midwives, doctors and nurses and the provision of support for the development and maintenance of infrastructure; such investment is required for referral mechanisms, equipment and supply chains to improve maternal and newborn health services, with functional quality control and monitoring mechanisms in place for all areas of service delivery, and for strengthening the capacity for surgery within the health-care system as part of efforts to achieve universal health coverage as part of the Sustainable Development Goals; (b) Developing or strengthening of comprehensive multidisciplinary national strategies, policies, action plans and budgets for eliminating obstetric fistula within a generation that incorporate prevention, treatment, socioeconomic reintegration and essential follow-up services, including incorporating a strategy to address fistula into national level planning, programming and budgeting for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals; (c) Establishing or strengthening of a national task force for addressing obstetric fistula, led by ministries of health, to enhance national coordination and improve partner collaboration, including partnering with efforts in-country to increase surgical capacity and promote universal access to essential and life-saving surgery; (d) Ensuring equitable access and coverage, by means of national plans, policies and programmes, to make maternal health-care services, in particular, emergency obstetric and newborn care, skilled birth attendance, obstetric fistula treatment and family planning, financially and culturally accessible, including in the most remote areas; (e) Ensuring universal access to the full continuum of care, particularly in rural and remote areas, through the establishment and distribution of health-care facilities and trained medical personnel, collaboration with the transport sector to provide affordable transport options and promotion of and support for communitybased solutions; (f) Increasing the availability of trained, skilled fistula surgeons and permanent, holistic fistula services integrated into strategically selected hospitals, along with quality assurance, including by ensuring that only skilled fistula surgeons provide treatment to address the significant backlog of women and girls awaiting care;

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Financial support

(g) Increasing national budgets for health care, ensuring that adequate funds are allocated to universal access to sexual and reproductive health services, including for obstetric fistula; (h) Incorporating, into all sectors of national budgets, policy and programmatic approaches to redress inequities and reach poor and vulnerable women and girls, including the provision of free or adequately subsidized maternal and newborn health-care services and obstetric fistula treatment to all those in need; (i) Enhancing international cooperation, including intensified technical and financial support, in particular to high-burden countries, to end obstetric fistula within a generation; (j) Mobilizing public and private sectors to ensure that the needed funding is increased, predictable, sustained and adequate to end fistula within a generation;

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Reintegration strategies and interventions

Ensuring that all women and girls who have undergone fistula treatment have access to social reintegration services, including counselling, education, skills development and income-generating activities;

Ensuring that the special needs of women and girls whose cases are deemed to be incurable or inoperable are met, in addition to providing other essential reintegration services;

Developing and strengthening systems and follow-up mechanisms to make fistula a nationally notifiable condition, including indicators to track the health, well-being and access to reintegration services of all fistula survivors;

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Advocacy and awareness-raising

Strengthening of awareness-raising and advocacy, including through the media, to effectively reach families and communities with key messages on fistula prevention, treatment and social reintegration;

Mobilizing communities, including local religious and community leaders, women and girls, men and boys, ensuring youth voices are heard, to advocate and support universal access to sexual and reproductive health services, ensuring reproductive rights and reducing stigma and discrimination;

Ensuring gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls, recognizing that the well-being of women and girls has a significant positive effect on the survival and health of children, families and societies;

Empowering of obstetric fistula survivors to sensitize and mobilize communities as advocates for fistula elimination and safe motherhood;

Strengthening and expanding interventions to ensure universal access to education, especially post-primary and beyond, end violence against women and girls and protect and promote their human rights; and adopting and enforcing laws prohibiting child marriage, which must be supported by innovative incentives for families to keep girls in school, including those in rural and remote communities, and avoid marrying them off at an early age;

Developing linkages and engagement with civil society organizations and women’s empowerment groups to help eliminate obstetric fistula.

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

End fistula within a generation.

In 2016, the international community again commemorated the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula under the theme, “End fistula within a generation”, calling for intensified efforts to eradicate fistula and achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

#International Day to End Obsteric Fistula#23 May#End Fistula Day#Sustainable Development Goal 3#sdg3

0 notes

Text

Research, data collection and analysis.

(t) Strengthening research, data collection, monitoring and evaluation, including up-to-date needs assessments, on emergency obstetric and newborn care, to guide the planning and implementation of maternal health programmes, including those for addressing obstetric fistula; (u) Developing, strengthening and integrating, within national health information systems, routine reviews of maternal deaths and near-miss cases as part of a national maternal death surveillance and response system; (v) Developing of a community- and facility-based mechanism for the systematic notification of obstetric fistula cases to ministries of health and their recording in a national register, and establishing obstetric fistula as a nationally notifiable condition, triggering immediate reporting, tracking and follow-up, with a human rights-based approach.

The challenge of putting an end to obstetric fistula within a generation requires vastly intensified efforts at the community, subnational, national, regional and international levels and the development of a global action plan to end fistula. Efforts must also include the strengthening of health-care systems, ensuring gender and socioeconomic equality, the empowerment of women and girls and the promotion and protection of their human rights. Substantial additional resources also need to be forthcoming to accelerate progress and end fistula and funding must be increased. As the international community moves to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, significantly enhanced support should be provided to countries, United Nations organizations, the Campaign to End Fistula and other global initiatives dedicated to improving maternal and newborn health and eliminating obstetric fistula

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula

0 notes

Text

Going from global to local — national leadership and strategies toward ending fistula.

In 2015, the United Nations marked the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula (23 May) with a special event held at the World Health Assembly, in Geneva. The event, hosted by the permanent missions of Ethiopia, Iceland and Liberia to the United Nations Office at Geneva and other international organizations, and by UNFPA, was entitled, “Going from global to local — national leadership and strategies toward ending fistula”. The event included a panel discussion focused on the importance of countries affected by fistula developing costed, time-bound national strategies for eliminating fistula. Strategies developed in Ethiopia and Liberia were shared as examples for prioritizing the issue at the national level. In addition, the occasion was commemorated with parallel activities by national authorities and partners of the Campaign to End Fistula throughout the world under the theme, “End fistula, restore women’s dignity”. In many countries, political leaders, celebrities, health professionals and civil society organizations took part in events that featured awareness-raising, media outreach and testimonies from fistula survivors on radio and television. Key messages called for fistula prevention, access to treatment and intensified actions to end obstetric fistula.

Over the past two years, sustained presence in the media, increased collaboration at the country and regional levels and enhanced coordination with partners has helped to ensure strong messaging and significant communications activities related to obstetric fistula. Efforts were made to mobilize countries in heavily affected regions as well as raise awareness about the condition worldwide. To that end, a documentary entitled “Suffering in Silence — Obstetric Fistula in Asia” was launched in 2015. The documentary increases awareness of the work of UNFPA and the Campaign to End Fistula to end obstetric fistula.

By 2015, countries with high maternal mortality rates had completed or initiated such assessments and almost all have translated their survey findings into action plans. Seven countries are monitoring progress made in relation to emergency obstetric and newborn care signal functions and the availability of skilled staff.

#Campaign to End Fistula#23 may#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula#United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)#World Health Organization (WHO)#world bank group#UN-Women#unicef

0 notes

Text

Improving the quality of obstetric care.

Obtaining robust and comprehensive data on fistula remains a challenge, particularly given the invisibility of fistula survivors and the lack of priority and resources directed towards the issue at the global and national levels. Progress has been made in improving the availability of data, including the development and application of a standardized fistula module for inclusion in demographic and health surveys in an increasing number of countries. In addition, the Global Fistula Map has been updated, enhanced and expanded and provides a snapshot of the landscape of fistula treatment capacity and gaps worldwide. During the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics meeting of fistula stakeholders in 2015, a call for improved data collection tools was made so that surgical centres in countries affected by fistula can share, collaborate and improve practice through evidence - based efforts. Recommendations have been made to integrate routine surveillance and monitoring of fistula into national health systems, instead of this being conducted only through small independent studies. Additional suggestions are to combine community and facility approaches to collecting data, continue surveillance of surgeries to track progress and train providers to diagnose and report fistula at post-partum visits.

While precise figures are not available, it is estimated that over two million women and girls are living with obstetric fistula. Responding to the call for cost-effective methods for obtaining robust data on fistula, a new model to estimate the global burden of fistula, known as the “Lives Saved Tool”, has been developed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which is piloting the model to generate global and country-specific estimates of fistula incidence and prevalence. The model will be applied to all countries supported by the Campaign to End Fistula so as to produce new global estimates on fistula. It constitutes a major step forward globally and a vital tool to advance the planning, implementation and monitoring of efforts towards ending fistula.

Evidence of the positive, powerful impact of midwives in preventing maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity was significantly strengthened over the past two years with the release of the State of the World’s Midwifery, 2014 and the Lancet Midwifery series. In the Lancet Midwifery series, the Lives Saved Tool wasas used to estimate deaths averted if midwifery was scaled up in 78 countries. With universal coverage of midwifery interventions for maternal and newborn health, including family planning, for the countries with the lowest indicators in relation to maternal mortality and morbidity, 83 per cent of all maternal, fetal and neonatal deaths could be prevented. The French version of the Lancet Midwifery series was jointly launched by the International Confederation of Midwives, UNFPA and WHO in early 2015 in Geneva.

Maternal death surveillance and response, a framework for addressing preventable maternal mortality and morbidity, is increasingly being promoted and institutionalized in several countries. Maternal death and severe morbidity near-miss case reviews are of crucial importance in improving the quality of obstetric care, which, in turn, prevents the occurrence of maternal death and disability, including obstetric fistula.

To prevent the occurrence of obstetric fistula, timely access to quality health care, including emergency obstetric services, is of paramount import ance. To that end, it is essential to assess the current level of care and provide the evidence needed for planning, monitoring, advocacy and resource mobilization to improve access to quality of care and scale up emergency services in every district. UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO and the Averting Maternal Death and Disabilities Programme at Columbia University support emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessments in countries with high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity.

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula#International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)#Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health#Lives Saved Tool

0 notes

Text

Intensifying efforts to end obstetric fistula.

Ending obstetric fistula is fundamental to reducing maternal mortality and morbidity and improving maternal and newborn health. Any woman or girl suffering from prolonged obstructed labour without timely access to an emergency Caesarean section is at high risk of developing obstetric fistula. Obstetric fistula is a severe maternal morbidity and a stark example of inequity. Although fistula has been virtually eliminated in many countries, it continues to afflict many poor women and girls worldwide who do not have access to health services. In order to eliminate fistula, it is necessary to scale up country capacity to provide access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care, treat fistula cases and address underlying health, socio-economic, cultural and human rights determinants. Countries must ensure universal access to reproductive health services; address gender-based and socio-economic inequities; prevent child marriage and early childbearing; promote universal education, especially for girls, eliminate sexual and gender-based violence, and promote and protect the human rights of women and girls.

Obstetric fistula has a catastrophic health impact for a woman and her child. If left untreated, it can lead to devastating, lifelong morbidity with serious medical, psychological and social consequences. Evidence shows that approximately 90 per cent of women who develop fistula deliver a stillborn baby.

A woman with fistula is not only left incontinent but may also experience neurological disorders, orthopaedic injury, bladder infections, painful sores, kidney failure or infertility. The odour from constant leakage, combined with misperceptions about its cause, often result in stigma and ostracism. Many women with fistula are abandoned by their husbands and families. They may find it difficult to secure income or support, thereby deepening their poverty. Their isolation may affect their mental health, resulting in depression, low self-esteem and even suicide. Preventing obstetric fistula requires addressing the root causes of maternal mortality and morbidity, including poverty, marginalization, gender and sociocultural inequality, barriers to education, especially for girls, child marriage and adolescent pregnancy. Health-care costs can be prohibitive and catastrophic for poor families, especially when complications occur. These factors contribute to the three categories of delay that impede women’s access to health care: (a) delay in seeking care; (b) delay in arriving at a health-care facility; and (c) delay in receiving appropriate and high-quality care once at the facility. Sustainable solutions for ending obstetric fistula therefore require functioning, strengthened health systems, well-trained health professionals, access to and supply of essential medicines and equipment and equitable access to high-quality reproductive health services. The three most cost-effective interventions to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, including fistula, are: (a) timely access to high-quality emergency obstetric and newborn care; (b) the presence of a trained health professional with midwifery skills at childbirth; and (c) universal access to family planning. Any woman or girl who experiences problems during childbirth and does not receive appropriate and timely medical care is at risk of developing obstetric fistula. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are a leading cause of death among girls between the ages of 15 and 19 years in many low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, at current rates, approximately 1 in 3 girls in low- and middle-income countries (excluding China) will marry before the age of 18. Child marriage and early pregnancy for girls, particularly in underresourced settings, puts them at risk for mortality and morbidity, including fistula. Impoverished, marginalized girls are more likely to be subjected to child marriage and become pregnant than girls who have greater education and economic opportunities. All adolescent girls and boys, both in and out of school, need access to health services, including those relating to sexual and reproductive health, to protect their well-being. Most cases of obstetric fistula can be treated through surgery, after which women and girls can be reintegrated into their communities with appropriate psychosocial, medical and economic support. However, there is a tremendous unmet need for fistula treatment. Currently, few health-care facilities are able to provide high-quality fistula surgery, owing with the necessary skills, as well as essential equipment and medical supplies. When services are available, many women are not aware of them or cannot afford or access them because of barriers, such as transportation costs. Tragically, at the current rate of surgeries performed, most women and girls with fistula will die without receiving treatment.

#Campaign to End Fistula#maternal and child health#Eliminating Obstetric Fistula#u.n. general assembly#Obstetric fistula#International Day to End Obstetric Fistula#23 May

0 notes