elfhater

20 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

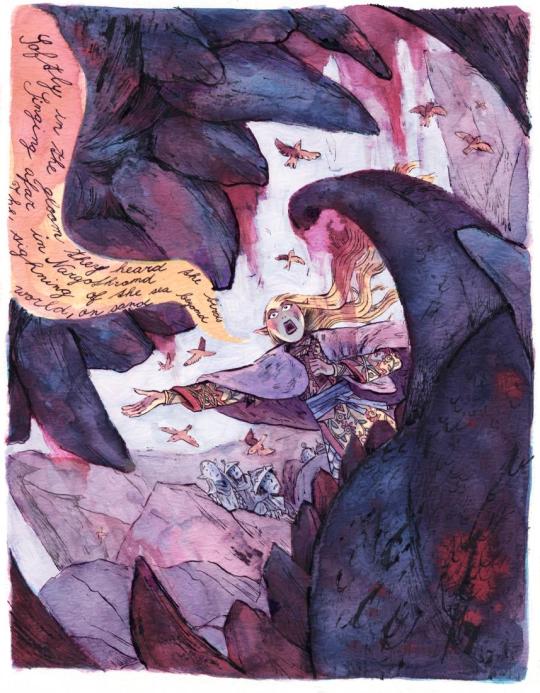

Finrod vs. Sauron! Collab with @s-u-w-i that took six months to finish :D Once again I wanted to do some weird composition for this scene. So I googled pictures taken from inside of animal mouths(bleh), to make gruesome Sauron ....and then Suwi made the final sketch since she can draw the cutest characters (and Finrod needs to be cute ♥)

#loveee#I was just wondering how someone could depict this scene to effectively give it movement&power and you nailed it#finrod

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Beleg Me and @chechula were listening to The Children of Húrin read by Christopher Lee. His dramatic voice fits perfectly 🐲💖

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

OKAY I understand thematically why Faramir and Éowyn make sense together and I can even see where some people who are REALLY into it are coming from.* BUT at the end of the day you have to be willing to take marriage-as-vehicle-for-life at face value. She's terrified of a cage, capture/oppression this whole time, spent a life in wartime...and then she meets Faramir who she can adjust to peace with...? In the binds of marriage...and that makes her happy. Nahhhhhhh vetoed

#debated posting this bc I know some people get really aggressive about this but I trust that my four (4) followers are reasonable ❤#*in fact this time around when I read the houses of healing I put myself in a farawyn fans shoes and I did go “aw thats beautiful"#and then I turned back into myself 🐛#I will probably make a tag for vague complaints probably so people can blacklist if they want bc i like to b.i.t.c.h.

0 notes

Text

Okay it does actually make me sad how little engagement there is with Denethor's character as he is actually written in the Denethor tag. #denethorapologist #yup

#Idk I get thinking hes an asshole because he is to be clear lol#but I dont get dismissing his character in general because he is sooo fascinating#let alone dismissing analysis of his character because he is “mean”#but I think atp that means our views on lit analysis are so vastly different as to be irreconcilable#In case anyone is wondering yeah. I do have the url denethorapologist saved

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Two Towers, King of the Golden Hall

The Return of the King, Minas Tirith

#I'm certain I'm not the first to notice this but I am obsessed#and this is not even getting into the “stone” comparisons. idk if that holds water but I have to find out#denethor#éowyn#lotr

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

túrin turambar and niënor níniel

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Think better of me" (traditional pen and ink)

#Obsessed with the panel of him stepping onto the pyre. Time to reread this chapter#denethor#faramir#lotr

930 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gigolas journey to Valinor which one do you pick

444 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Evil have been all thy ways, son of Húrin.”

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

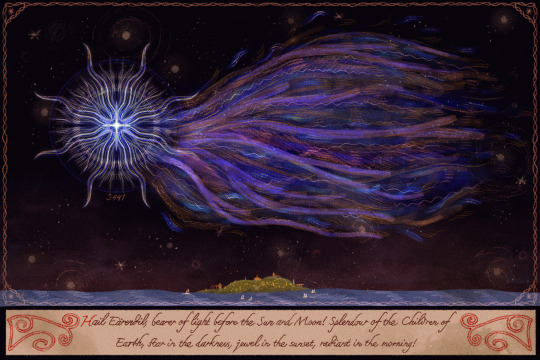

eärendil the mariner soaring over númenor in star form

inspired by the book of miracles

526 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is part of the framing device of LOTR that Tolkien isn’t the author, that he’s merely translating an ancient manuscript into modern English. The real author of The Hobbit is Bilbo, the real author of LOTR is Frodo and to a lesser extent, Sam. However, Tolkien isn’t actually very interested in the literary conceit that the narrators of his third-person narratives are characters within those narratives. He’s using the appendix “on translation” as a pretext to explain his clever use of Old English and Norse in place names, he’s using an unreliable narrator exactly once, to explain the difference between two editions of the Hobbit, and he’s fascinated by the idea of characters comparing their lives to stories or trying to understand their lives as stories, but very little of that actually goes into the narration.

In a Doylist sense, I’m willing to say that the novels are not at all written from the subjective POV of the characters that have supposedly written them. I’ve recently read the Book of the New Sun and also Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, very different books that both engaged deeply with the narrator being present in the story, with the massive gap between the narrator writing in the “present day” and the past self that he narrates. LOTR doesn’t do that, this isn’t meant to be a criticism, just a statement: it is a books that books can sometimes do, and LOTR is not doing it, it cares about other things.

But in a Watsonian sense, a lot of interesting questions come up when you take the conceit seriously and accept these characters as the author of their own story. Bilbo might be the easiest: The Hobbit is a children’s story because he’s chosen to tell it as a children’s story, probably for young Frodo himself. The story he’s telling is mostly light-hearted, and he’s poking fun at himself all the time, and he’s also poking fun at the dwarves a lot. The Hobbit addresses the reader in a way later LOTR rarely does, saying “you can imagine how poor Bilbo felt when X happened” or “you can probably already see the flaw in Y plan.” Some of these might be responses to interjections, to questions and criticisms little Frodo voiced when first hearing the stories.

Frodo’s narrative voice is different, much more serious, since he’s writing for grown-ups from the beginning. I don’t mind that he’d described many events where he wasn’t personally present: I can imagine that he had long conversations with the other members of the fellowship, especially Merry and Pippin, and then turning his notes of their account into a narrative that’s filtered through his own sense of narrative, humour and aesthetics. Frodo basically just ghostwrote those chapters, based on lengthy interviews. The really weird thing comes in with the account of events that Frodo personally experienced. Fellowship starts with Bilbo, then shifts to a point-of-view focused fairly narrowly on Frodo, with some brief detours into the perspectives of the other hobbits. In Towers, we’re already firmly in Sam’s perspective, we see most of Frodo’s actions through Sam’s eyes, and we mostly stay in that perspective until the end of the trilogy. If Frodo wrote this book: why? Why not write of his own experiences, as he did in the previous chapters? (Of course there’s the Doylist answer, Tolkien decided that Sam’s POV was more compelling and that Frodo’s struggle with the ring was more interesting shown from an outside perspective and probably impossible to write from an inside one. But what’s the Watsonian answer?)

One possible answer is that Frodo chose to write it that way, write it focused on Sam and not himself, either because to focus on himself would have hurt too much, or because he wanted to highlight Sam’s importance, to show him as the real hero. (Note to self: Gertrude Stein wrote Alice B. Toklas’s autobiography, I probably need to check that out.) There’s also the possibility that Sam wrote those chapters. Frodo tells him it’s his job to finish the book, and the usual reading is that Sam merely wrote the end of the Grey Havens chapter, but we can argue that the book was quite unfinished, and Sam had a larger part in more of it. It’s possible that Sam read Frodo’s chapters on the ring quest and figured that he had to rewrite them from scratch. It’s possible that Frodo found it so painful to write about that it’s just dry, brief outlines. “Crossed the tunnel. Big spider got me. etc.”, the whole thing is like five pages. Maybe memories formed under the influence of the ring are no longer wholly accessible: having lost the ring, they are distant, spectral, like they happened to someone else. Or maybe the ring actually warped Frodo’s memories and thoughts of those events to the point that what he wrote is just fifteen chapters of Book of Revelations level hallucinatory horror, wholly incomprehensible to anyone else. And of course there’s the possibility that during those chapters, Frodo has acted in a way, or at least thought and felt in a way, that Sam doesn’t want to share with the world. Sam is covering up that the journey was even harder, and that Frodo was corrupted by the ring in worse and sadder ways, and so he’s rewriting Frodo’s chapters to protect his memory.

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about explanations vis à vis angrist in the lay of leithian, the question being whether or not it was the knife, the wielder, or the forger (or some triangulation of multiple factors??) that made it possible for beren and lúthien to cut the silmaril free. the appeal of it being simply the knife itself is great for dharmic dramatic irony punished-by-the-narrative significance, since curufin had possession of something that could have fulfilled the oath and just didn't know it (!!!!), but the idea that it was beren and lúthien in particular who allowed angrist to cleave through morgoth's crown lines up nicely with the general fairy-tale logic of leithian. that it was their courage and fierce hope prising the silmaril out and the knife was just an accessory. curufin couldn't've done it even if he'd tried—in fact, maybe he lost angrist because of his own actions, and in true fairy-tale fashion it went to those who best merited it. and then there's the possibility that telchar was just on something different, which doesn't have any narrative bearing that i can figure out.. and of course it's always also feasible that nothing was special or different, and any sharp object could have done the job, it's just that no one tried. which has a nice sort of futility to it all in all

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why does Eowyn want to die?

Because Aragorn won’t love her? Because she feels trapped in her feminine gender role?

These are the explanations we get in the text. However, none of the characters really acknowledge Eowyn’s darkest fear: being taken alive by the enemy.

There are some bad takes on Eowyn that boil down to patronizing her and downplaying the seriousness of her problems. People say that she had a naive desire for glory and Faramir teaches her that war isn’t actually fun. Then there’s the whole “Eowyn was a deserter who selfishly ran away from her duty” argument.

You can only say these things if you ignore how dire the situation was, how close Sauron was to winning, and how gruesome Eowyn’s fate would have been if he won. She knew that death or capture likely awaited her, and she knew that dying in battle was the least bad option. (She also knew her own worth and believed that she was too useful a warrior to be left behind with the civilians. And she was right.)

Eowyn’s actions are ruthlessly practical! She wants to die fighting because that’s better than waiting around for The Horrors. Let’s be real, Eowyn is too sensible to be suicidal over an unrequited crush.

Here are some of her most revealing quotes:

“All your words are but to say: you are a woman, and your part is in the house. But when the men have died in battle and honor, you have leave to be burned in the house, for the men will need it no more.”

“And those who have not swords can still die upon them.”

“Nor is it always evil to die in battle, even in bitter pain. Were I permitted, in this dark hour I would choose the latter.”

“But I do not desire healing…. I wish to ride to war like my brother Éomer, or better like Théoden the king, for he died and has both honour and peace.”

In the end, Eowyn only stops wanting to die after Sauron is defeated. Just before the Ring is destroyed, she tells Faramir:

“I stand upon some dreadful brink, and it is utterly dark in the abyss before my feet, but whether there is any light behind me I cannot tell. For I cannot turn yet. I wait for some stroke of doom.”

Eowyn can’t turn to light and life until the war is over. Hope is too painful; death at least offers “honor and peace.” This passage is so important because it EXPLICITLY links Eowyn’s despair to the outcome of the war and makes it clear that she is not simply having a meltdown because Aragorn rejected her.

There are two important moments where Eowyn is threatened with violence. The very first time we meet her, we are told by Gandalf that Wormtongue planned to turn her into a sex slave after Saruman conquered Rohan. Even though this threat is dismissed quickly, it’s a disturbing reminder of what could happen to Eowyn if Sauron wins.

Then we have the most triumphant moment of Eowyn’s story: her battle with the Witch King. Once again, Eowyn is not threatened with death, but with captivity and torment:

“Come not between the Nazgûl and his prey! Or he will not slay thee in thy turn. He will bear thee away to the houses of lamentation, beyond all darkness, where thy flesh shall be devoured, and thy shrivelled mind be left naked to the Lidless Eye.”

Eowyn laughs at him and makes sure to announce that she is a woman before killing him. Her victory is all the more satisfying because the Witch King has just threatened her with captivity, loss of agency, the violation of her body and mind—all threats that Eowyn has faced before. But the Witch King’s words continue to haunt Eowyn and us. He threatens to withhold death; and death is therefore framed as an escape, a gift. Eowyn is taken to the Houses of Healing, but she is obsessed with returning to battle and fighting until she dies.

When Eowyn says that she fears “a cage,” this is a brilliantly simple metaphor for the entire spectrum of oppression she has faced: from the well-meaning restrictions of her culture to the horrifying enslavement threatened by Wormtongue.

Once the war is over, Eowyn is able to laugh at her fears. She teases Faramir: “And would you have your proud folk say of you: there goes a lord who tamed a wild shieldmaiden of the North!” Her fear of being caged has been turned into a bit of flirtatious banter. She feels completely safe with Faramir, and the idea that he “tamed” her is nothing but a joke between them.

2K notes

·

View notes