A blog featuring discussions surrounding the content of #MDA20009

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Gaslighting has become a major problem on social media platforms. Due to this, individuals and groups have begun to establish responses to gaslighting behaviours to ‘call out’ the behavior and try to minimize its use on social media.

Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation in which a person seeks to sow seeds of doubt in a targeted individual or in members of a targeted group, making them question their own memory, perception, and sanity. Using persistent denial, misdirection, contradiction, and lying, gaslighting involves attempts to destabilize the victim and delegitimize the victim's belief.

Instances may range from the denial by an abuser that previous abusive incidents ever occurred to the staging of bizarre events by the abuser with the intention of disorienting the victim. The term originated from the 1938 Patrick Hamilton play Gaslight and its 1940 and 1944 film adaptations, in which the gas-fueled lights in a character's home are dimmed when he turns the attic lights brighter while he searches the attic at night. He convinces his wife that she is imagining the change. The term has been used in clinical and research literature, as well as in political commentary.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Media: facilitating abuse and hatred? (Week 10)

Within the ‘real world’, people generally understand what bullying is and what it looks like. However, bullying, trolling and other negative-centric behaviours are less easily deciphered from behind a screen. For the many benefits that social media affords its users; collaborativity, communication and collectivity, social media also presents very real and dangerous challenges to those who choose to use it. Now, more than ever, harassment and abuse on social media is at a high. This increased level of harassment means that members of society who are already vulnerable face additional abuse.

Gaslighting is the behaviour of “psychologically manipulating a person in order to erode their sense of self and sanity” (Gleeson 2018). Gaslighting, like many other bullying tactics, originated beyond a screen, however the proliferation of social media and the ability to simulate ‘in person’ interactions has meant the behaviour of gaslighting has become commonplace on social media platforms. Gaslighting is particularly alarming within the online context due to its ability to “unnerve and demoralise” (Gleeson 2018) people.

Social media is often utilised by support groups and social justice movements, using these platforms to inform the masses of issues and invoke change. However, the emergence of gaslighting techniques on social media has aimed to discredit and devalue these groups and movements. For example, the recent #MeToo movement, which encouraged women particularly to publicise situations in which they had been subject to sexual harassment or abuse. However, gaslighting on social media platforms aimed to “dismiss” (Gleeson 2018) these publications, instead stating that these “survivors: had “misread the situation” (Gleeson 2018) or “imagined the abuse” (Gleeson 2018).

However, the increase of harassment and abuse on social media is not limited to specific behaviours such as gaslighting. Harassment and abuse can be harboured on social media merely through groups projecting and posting hateful and ill-informed views and thought on particular subjects.

As identified by Marwick, “harassing behaviours” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543) online are becoming more “networked” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543), “coordinated and organised” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543). That is, users of social media are beginning to organise themselves “loosely” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543) into their own social media “networks” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543) constituting “blogs, podcasts and forums” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543), to engage and spread common thought.

Recently, this has been evidence by the emergence of the “manosphere” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543), a social media network which aims to spread messages of “men’s rights” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 550) and hence dismiss “feminist thought” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 550) and female equality generally. Like many other collective networks, the “manosphere” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543) uses vocabulary and language to connect users to a “common” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 553) community and hence “identity” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 553). As the “manosphere” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 543) is really a collective of many different and “diverse” (Marwick et al, 2018, p. 553) online communities, the use of common language and vocabulary connects these varying communities and therefore evolves the community of hatred and bullying.

Hence, whilst the formation of online networks of similar thought is not inherently subjecting others to harassment and abuse, when these communities main objectives is to spread messages of hatred towards a particular sector in society, these networks further contribute to conflict and bullying on social media. Ultimately, disintegrating the safety and positivity social media aims to employ.

Social media affords many benefits to those who chose to use it. However, these benefits in recent times are potentially being outweighed by the movement of bullying and harassment into online spaces. Whilst this negativity severely disrupts the main objectives of social media in modern society, awareness and reporting of common bullying techniques and networks can assist in alleviating and reducing harassment and abuse online.

References:

Jessamy Gleeson, Research Officer, School of Global, Urban & Social Studies, RMIT University, 'What does Gaslighting Mean?' The Conversation, 2018 , https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-does-gaslighting-mean-107888

Alice E. Marwick & Robyn Caplan, 'Drinking male tears: language, the manosphere, and networked harassment' Feminist Media Studies Volume 18, 2018 - Issue 4: Pages 543-559

#online bullying#social media hate#gaslighting#manosphere#digitaldiscussions#digital communities#social media conflict#mda20009#mda2000921#public sphere

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

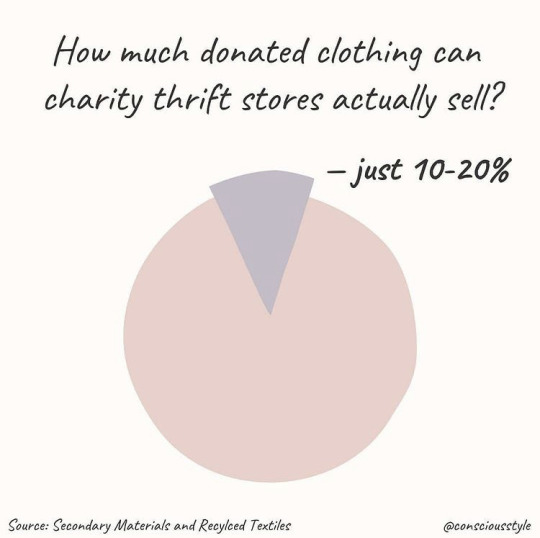

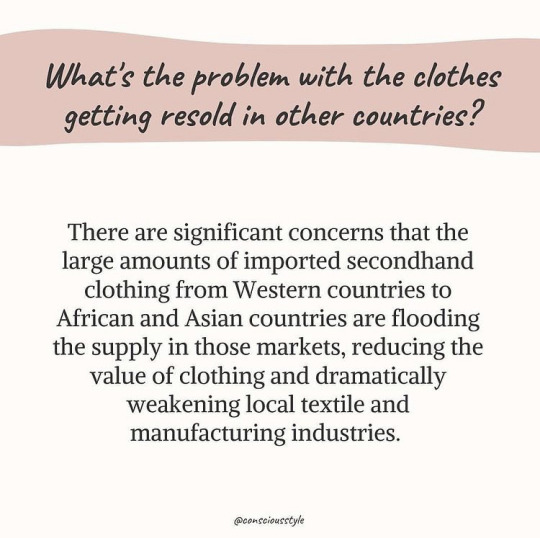

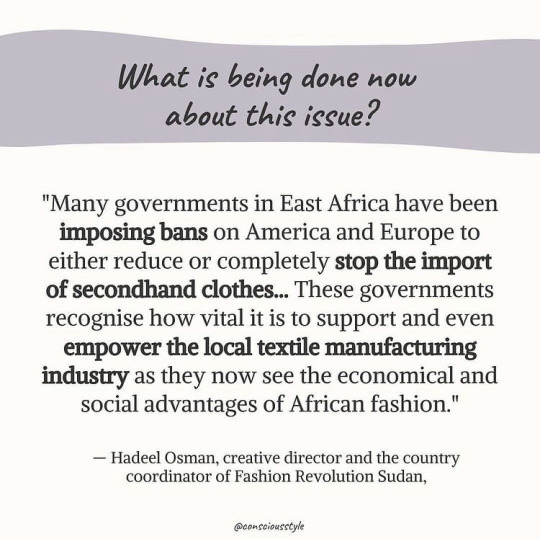

Try to be conscious of where your donations are going. Be proactive to give your garments their longest life and use this too to help you shop responsibly.

(Photo credit to consciousstyle on Instagram)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Media: encouraging unsustainable and unethical fashion? (Week 9)

Social Media is known to establish trends; dances, food, photography. In particular, social media is a catalyst for new fashion trends. The ability for an influencer to post a photo in a particular outfit, and simultaneously compel their followers to buy similar outfits or clothing from that brand is a testament to the power of social media within modern society. However, with this power, comes great responsibility, and unfortunately, this responsibility has been lacking within recent years. Whilst influencers are great at setting trends and influencing the decisions, opinions and purchasing habits of consumers, regarding fashion and clothing, these influencers are less effective at ensuring the promotion of sustainable and ethical fashion.

Sustainable fashion refers to those ‘goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimizing the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life-cycle, so as not to jeopardize the needs of future generations’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 83). Generally, sustainable fashion rejects the unethical nature of fast fashion, denouncing the ‘throw away attitude’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82) of ‘mass-produced’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82 ) and ‘cheap’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82) clothing. Sustainable fashion promotes the use of ethically sourced materials and production of clothing in an effort to limit the amount of textile waste that the fashion industry produces.

There have been huge efforts of recent years within the fashion industry to reform unethical and unsustainable productions and manufacturing. Brands such as H&M, Nike, Adidas and Levis are leading the charge in sourcing sustainable materials for their products and innovating new and ethical forms of production. Despite this, the benefits of sustainable fashion are still significantly threatened by social media and the relationship between influencers and fast-fashion.

Lai identified that whilst consumers generally understand and agree that the fashion industry needs to ‘change’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88) and ‘become more environmentally and socially responsible’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88), they have little ‘awareness’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88) about the sustainable fashion movement. Moreover, whilst consumers generally associate sustainable fashion with ‘natural’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 89), ‘simple’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 89) and ‘locally made’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 89) clothing, the lack of ‘awareness’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88) about what the movement is trying to achieve leads these consumers to develop negative ‘perceptions and attitudes’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88) towards it.

The lack of awareness surrounding the sustainable fashion movement can be correlated with the impact of influencers and fast fashion on social media. Many consumers buy clothing based on what their favourite influencers are wearing. Unfortunately, however, many influencers do not actively seek to post about sustainable fashion. As influencers can directly influence the purchasing habits of their followers, posting paid sponsorships with fast fashion companies also directly compels these followers to become consumers of fast fashion.

Moreover, through influencers not actively getting involved in the sustainable fashion movement, negative ‘perceptions and attitudes’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 88) towards the movement are encouraged. These perceptions include that sustainable fashion is ‘less fashionable’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 92) than its ‘fast fashion counterparts’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 92), and that sustainable fashion is ‘too expensive’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 91). Through the proliferation of these perceptions, the sustainable fashion movement’s main objectives are forgotten, and it becomes more difficult to hold the fashion industry accountable for its large contributions to the environmental crisis.

Despite this, there is still hope. Influencers can take responsibility on their platforms to inform and compel their audiences to choose sustainable fashion over fast fashion. Through doing so, the demand for fast fashion will slowly decrease, and so will the need for the unethical production of ‘mass-produced’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82) and ‘cheap’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82) clothing, that only purports a ‘throw away’ (Lai et al 2017, pg. 82) culture.

References:

Zhen Lai, Claudia E. Henninger and Panayiota J. Alevizou ‘An Exploration of Consumers’ Perceptions Towards Sustainable Fashion – A Qualitative Study in the UK’, in Sustainability in Fashion A Cradle to Upcycle Approach, edited by Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P., Goworek, H., Ryding, D. (Palgrave: 2017).

References:

#digitaldiscussions#digital#fast fashion#sustainable fashion#ethical fashion#digital citizenship#digitial citizen#public sphere#climate change#influencers#mda20009#mda2000921#digital communities

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

With the COVID-19 pandemic, social interactions has been significantly limited. Despite this, online gaming offers a vital opportunity for important interaction among friends and strangers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Social Gaming: a civic and political domain? (Week 8)

The world of online and offline gaming is not normally linked to the civic and political domain, or greater sociological studies. Often thought of as a form of leisure or fun, gaming is yet to be taken seriously as a form of entertainment that is intrinsically linked to mainstream issues. Despite this, Taylor argues that gaming is an important aspect of the ‘media and socio technical landscape’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11)

Gaming has undergone significant changes across recent decades. Initially concerned with ‘arcades’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4) and ‘home concelse machines’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4), gaming evolved into ‘internet gaming’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4) whereby ‘multiplayer connections’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4) became available, creating a more ‘competitive space’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4). Currently, gaming has been transformed into a ‘televisual’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4) activity with the ‘core of its growth’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4) vested in ‘live streaming’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 4).

Liver streaming is an incredibly popular aspect of the current gaming landscape. At its core, live streaming enables a participant or player to ‘broadcast’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 3) their game to many people ‘watching’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 10) through online platforms such as ‘Twitch’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 3) and ‘Youtube’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 3), straight from their own homes. Through these platforms, other players can use ‘chat’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11) features to communicate with the player or can even play ‘alongside’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6) them. Essentially, live streaming enables gamers to ‘transform their private play into public entertainment’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6).

However, live stream gaming provides social benefits to its audiences as well. People watching along a live stream are able to become ‘integrated into the show’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6) through chatting with the broadcaster about the game itself or ‘everyday life’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6). Live streaming has evolved from initially just broadcasting a streamer playing a game to creating a ‘new form of entertainment’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 9) whereby ‘gameplay, humor, commentary’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 9) are all a part of the experience. Now, live streaming offers players an ‘opportunity to build audiences’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6) around their own gameplay that share similar ‘interests’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6). Thus, through live streaming, gaming has become a social and interactive phenomenon whereby gamers and audience members alike can use a game to form social connections.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, gaming offers an opportunity for people to interact in the civil and political domain. As identified by Taylor, gaming is a form of ‘leisure’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11), often used to come home and ‘tune out from the real world’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11). However, gaming is becoming a space frequently used for civic and political discussion. Players are ‘regularly encountering’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11) people from ‘outside their own social worlds’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 11), such as ‘race, sexuality and social identity’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 12). Moreover, the games themselves are becoming increasingly politicised with ‘companies, policies and laws’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 12) addressing issues from ‘intellectual property to standards of behaviour’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 12). This has led to the world of gaming becoming a ‘politically infused space’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 12) rather than an solely entertainment space. As highlighted by Taylor, gaming has become a platform whereby ‘important political and critical conversations’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 13) regarding civic and political life are shared. This is due to the relative connection shared between streamer and audience and the lack of corporate structure within this relationship - streamers broadcast their streams from their own ‘private lives’ (Taylor 2018, pg. 6).

Ultimately, gaming provides an important social space for players and audience members alike to connect and communicate with one another. Through the relative connection live streaming affords its participants, gaming has become a civic space.

References:

Taylor, TL 2018, ‘Broadcasting ourselves’ (chapter 1), in Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming, Princeton University Press, pp.1-23

#digitaldiscussions#digital#political domain#civic space#digital citizenship#digital citizen#public sphere#mda20009#mda2000921#gaming#livestreaming#digital communities#twitch#youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Compelling read highlighting the connection between technological face filters and in-person makeup

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Media: portraying unrealistic beauty standards through filters? (Week 7)

The use of filters on social media platforms has not only increased within recent years, but has become normalised within ‘online and offline’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 7) communities. Whilst these filters have the potential to harm perceptions of ‘attractiveness’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 8) for both women and men, as highlighted by Coy-Dibley, these filters and ‘technological modification’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) of images generally has a greater potential to harm women through their imposition of unrealistic ‘representations’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) and ‘beauty standards’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) for women.

Within all forms of media, women’s bodies are constantly critiqued and judged by the wider community. Too thin, large, small, not big enough, not clear enough, not white enough, it is extremely difficult for a woman to conform to the constantly changing nature of what society deems as ‘visually attractive’. Women are constantly surrounded by these critiques in ‘daily TV shows, women’s magazines, fashion adverts and media images’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 3). Within the digital sphere, there has been an emergence of ‘technological modification’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) applications such as ‘Perfect365’ or ‘Facetune’ which allow a person to alter their appearance to their or society’s deriable notions of attractiveness. These types of applications specifically promote themselves to female demographics (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 4). Alongside these modification applications is the general rise in filters which allow social media users to change features on their faces. Thus, as argued by Coy-Dibley, people now no longer critique their ‘bodies in mirrors’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 4), but these same people can ‘digitize their dysmorphia’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 1) through ‘virtually modifying’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 1) themselves.

Hence, the phenomena of ‘digital dysmorphia’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 1) has evolved. Digital dysmorphia exists on the ‘spectrum with Body Dysmorphic Disorder’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2), however is shaped by ‘societal pressures’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2), ‘constructs of beauty’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) and the ‘technology available to attain these’ beauty ‘standards’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2). Digital dysmorphia typically ‘manifests’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) itself in women, in ‘Western cultures’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2). Digital Dysmorphia relates to women who ‘see their bodies as flawed in reality’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2)and therefore ‘edit their images digitally’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2), to ‘correct’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2) their perceived flaws. Through this process, images ‘transcend the material anatomical body’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2), and instead ‘form a digitally reconstructed ideal self-image’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 2).

Digital Dysmorphia is problematic for numerous reasons. Digital Dysmorphia highlights the unrealistic notions of attractiveness that are perpetuated through social media. The use of face filters and photo editing applications further internalise highly unachievable body images and appearances for women to obtain. Essentially demonstrating how women are ‘inclined to alter their body images’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 5), due to ‘pressures to look a certain way’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 5). Moreover, these unrealistic notions of attractiveness further enforce ‘inescapable hetero-sexy ideals of feminity’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 4).

However, the use of face filters and photo editing applications can confer positive attributes for society. As suggested by Coy-Dibley, through ‘modifying the image of oneself’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 6), people can feel ‘liberated’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 6) or ‘relief’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 6) that they can ‘embody unattainable social standards’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 6). Moreover, through using these types of alteration features, people can be free to creatively express themselves digitally, rather than through other more permanent means. Ultimately, these types of applications in some way promote individualism. Whilst they are based on dangerous and harmful ideals of beauty and attractiveness, users are seeking to modify themselves to look like a version of themselves they feel confident with, rather than other celebrities or influences they wish to look like. Essentially, these applications allow users to liberate themselves from the ‘shackles of the physical body’ (Coy-Dibley 2016, pg 9).

References:

Coy-Dibley, I. (July, 2016). “Digitised Dysmorphia” of the Female Body: The Re/Disfigurement of the Image . Palgrave Communications. 2:16040 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2016.40

#face filters#facetune#attractiveness#beauty standards#instagram#digital community#digital communities#public sphere#mda20009#mda2000921#social media#digitaldiscussions

1 note

·

View note

Text

Social Media: encouraging plastic surgery? (Week 6)

It is widely understood that social media is capable of connecting users in a way that traditional forms of media cannot. Unlike traditional forms of media, social media can be used as a mundane platform, whereby people post pictures and videos relating to their personal lives, or a commercial platform, whereby professionals and business people alike use the connectivity and instant-reach provided by social media to sell to impressionable consumers. Recently, social media has evolved to become a digital infrastructure capable of advertising and promoting plastic surgery procedures.

As identified by Dorfman, Instagram in particular is a ‘natural suit’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 332) for ‘business marketing’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 333) surrounding plastic surgery. This is because Instagram is a photo and video sharing platform and plastic surgery is a ‘visual surgical specialty’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 332). Through using Instagram, plastic surgeons are able to post photos and videos of procedures, before and after comparisons and also market their procedures to a desirable audience.

However, whilst it appears that social media and plastic surgery is the perfect match, this relationship is bittersweet.

It is advantageous for plastic surgeons to use social media as a marketing tool to gain new clientele. With more and more people interacting and using social media, plastic surgeons will continue to gain more interest and enquiries via these platforms. However, whilst social media is a great marketing tool, it is not the most professional nor educational tool consumers should use to inform themselves about plastic surgery procedures. Dorfman’s research indicated that a vast number of posts under the hashtag ‘plastic surgery’ were ‘self-promotion’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 334) rather than ‘education’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 334). With an increasing number of plastic surgery patients using social media as a ‘consultation’ service to inform themselves of plastic surgery procedures, self-promotional posts or posts from nonplastic surgeons may be detrimental to potential consumers.

Additionally, through the continued use of social media by plastic surgeons for self-promotion, the procedures of plastic surgery have become a ‘trivialised aesthetic’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 335), rather than an understood medical procedure. This aesthetic coupled with a lack of ‘board-certified plastic surgeons’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 334) posting to popular social media hashtags used by consumers to inform themselves of procedures, produces a dangerous situation whereby consumers can be falsely enticed into a surgery that they know little about. With a lack of educational posts surrounding plastic surgery, consumers are unlikely to be properly exposed to the ‘risks and dangers’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 336) of plastic surgery.

Ultimately, social media presents a valuable option for plastic surgeons to inform and gain new clientele. However, there are significant risks to using social media to inform and advertise plastic surgery. Whilst there is an abundance of self-promotional content regarding plastic surgery on social media platforms, there is a significant deficit of educational content regarding the risks and dangers of plastic surgery . Moreover, there is a lack of ‘board-certified plastic surgeons’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 334) using social media to inform these consumers, instead popular plastic surgery posts are often posed by nonplastic surgeons. To combat these issues, as argued by Dorfman, more ‘board-certified plastic surgeons’ (Dorfman et al. 2018, pg 334) should post to social media, adequately informing potential consumers of the benefits and risks of plastic surgery procedures.

References:

Robert G Dorfman, Elbert E Vaca, Eitezaz Mahmood, Neil A Fine and Clark F Schierle, ‘Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing’, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 38, Issue 3, March 2018, pp 332–338

#digitaldiscussiondigitalsocialmediamda20009mda200091digitalcitizenshipdigitalcitizenpoliticspoliticalengagementactivismactivistpublicsphered#digitaldiscussion#digital#socialmedia#mda20009#mda2000921#digitalcitizenship#digital citizen#plastic surgery#cosmetic surgery#public sphere#instagram

1 note

·

View note

Quote

New citizen norms and identities have emerged that prioritise personalisation and sharing over traditional, dutiful allegiances to politics

Ariadne Vromen in Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement: The Challenge for Online Campaigning and Advocacy Organisations

1 note

·

View note

Text

Social Media: A cause for political engagement? (Week 5)

Social media is known to foster communication between people. Considered as a forum to post interesting photos of yourself/others or what you are doing/interested in, social media is not often associated with the world of politics and activism. However, with the increased use of social media and recent “advances” (Law et al 2018) in “digital communication platforms” (Law et al 2018), social media has transformed into a digital infrastructure aiding political engagement. Social media allows for the “distribution of ideas” (Law et al 2018) and “public deliberation” (Law et al 2018). Through this, social media inherently promotes the sharing of political ideas and political discussion

The unique feature of hashtags, or specifically hashtag publics further helps social media facilitate political engagement. Hashtags use specific words or abbreviations to connect or “affiliate” (Zappavigna) different posts together. Through different themes and keywords, ideas and discussions can instantly be connected. Additionally, whilst hashtags generate “ambient affiliation” (Zappavigna) between those who use them within a post, other users who merely wish to engage with the content of a specific hashtag public can search for that hashtag whereby all posts that have used it are coordinated. Hence, hashtags can help to coordinate political ideas, events and experiences and allow those interested in those ideas to engage with them. Ultimately, hashtags “aid the formation and coordination of ‘ad hoc issue publics’” (Bruns & Burgess; Rambukkana). Users of social media who wish to express a political opinion, idea or experience can use a specific hashtag whereby any experiences similar to can also be coordinated.

Ultimately social media, whilst often considered a mundane digital infrastructure, has become a forum to promote and engage issues of politics and activism. Political engagement within “advanced democracies” (Vromen 2017, p.2) has “changed” (Vromen 2017, p.2) within the last few years. No longer do citizens solely align with “traditional, dutiful allegiances” (Vromen 2017, p.2) of politics, such as political parties and trade unions, to engage with political issues. More often, citizens are now engaging with politics in a more “individualised” (Vromen 2017, p.3) way, specifically using “everyday digitally based mechanisms” (Vromen 2017, p.3) to “engage in politics” (Vromen 2017, p.3) and “express points of view” (Vromen 2017, p.3). This is due to the connectivity and availability social media affords its users.

Moreover, within the modern era, many people are digitally literate. They can understand how internet applications work, and can communicate effectively using different social media platforms. Hence, many generations today represent ‘digital citizens’. The concept of a digital citizen can be used to articulate how social media can be used to foster political engagement. A digital citizen is a person who has the “skills and knowledge” (Office of the eSaftey Commissioner, NSW Department of Education) to “effectively use digital technologies” (Office of the eSaftey Commissioner, NSW Department of Education). Moreover, a digital citizen uses these skills to “positively participate in society and communicate with others” (Office of the eSaftey Commissioner, NSW Department of Education). Through using social media applications, people can effectively share their political opinions/ideas/experiences within one another. Additionally, social media can be used as a forum for political discussion, whereby different people can discuss different political events or efforts that require more attention from the public.

Ultimately, the advances of social media coupled with its increased use and literacy means that everyday citizens can use social media to engage in politics, outside the constraints of traditional and formal political engagement.

References:

Ariadne Vromen (2017) Intro, Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement The Challenge from Online Campaigning and Advocacy Organisations London : Palgrave Macmillan

#digitaldiscussion#digital#socialmedia#mda20009#mda200091#digitalcitizenship#digitalcitizen#politics#politicalengagement#activism#activist#publicsphere#digital communities

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reality TV: a means for political discussion? (Week 4)

Many different adjectives are often used to describe the world of Reality TV; “trashy”, “entertaining”, “inappropriate” or “funny”. The sheer variety Reality TV offers from dating programs to talent contests, Reality TV is sure to provide entertainment to its viewers. Theories, studies or scholarships are not usually associated with the world of drama produced on Reality TV. However, the polarising nature of Reality TV and the growing connection between social media and these tv shows has led to discussion surrounding the ability of Reality TV to “trigger” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 18) social and political discussion in a “net-based public sphere” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 18).

Reality TV shows require “ordinary” (Nabi 2007) people to “engage in unscripted action and interaction” (Nabi 2007). Due to this, these shows inherently expose their audiences to ‘everyday’ issues, challenges or conversations, most of which have a “political dimension” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 19). Reality TV hence poses an opportunity for the audience to “make connections” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 20) between their own “personal experiences” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 20) and the issues present within the TV show. These connections can be fostered through social media. As identified by Graham and Hajru, social media creates an “alternative space” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 20 ) where the “politicization of everyday life issues can happen” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 20), in particular the everyday life issues apparent within Reality TV programs.

Hence, Reality TV shows allow digital communities, specific to the program, to be created, whereby audience members can interact and discuss the issues exposed and raised within the show. Content within a Reality TV program often causes a strong reaction from its audience. “Behaviour” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 27), “statements and discussions” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 27), “lifestyle, image and identity” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 27) are some of the activities within a Reality TV show that have been identified as “triggers” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 18) for online political discussion between audience members.

This has often been seen with the controversial Reality TV show Married at First Sight. The nature of the TV show, requiring complete strangers to marry each other and filming their ability to form an actual relationship over a period of time, often ignites strong discussion on social media between audience members. The hashtag #MAFS often trends during the airing of each episode and contains various interactions between viewers describing their thoughts and attitudes towards the content of the episode. These discussions often engage with topics such as gender, and discrimiation. Importantly, as these discussions take place on social media, anyone can engage with these discussions or contribute, promoting greater accessibility to a greater audience.

Additionally, Reality TV shows also encourage fans and contestants to interact with one another on social media, further fostering the creation of digital communities. These interactions often involve controversial points of discussion. For example, ex-bachelor star Abbie Chatfield often used her social media platform to explain issues of behaviour, image and identity portrayed on her season of The Bachelor. Through this, audience members were able to express their attitudes and thoughts of these issues, which have a “political dimension” (Graham and Hajru 2011, p. 19) to them.

Ultimately, the increased use of social media coupled with the overt popularity of Reality TV shows poists the opportunity for new digital communities to be created whereby political discussions can be expressed.

References:

Todd Graham and Auli Hajru Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere , European Journal of Communication 26(1) 18–32, 2011.

#digitaldiscussions#digitalcommunities#digital#social media#social media activism#social media politics#mda20009#publicsphere#mafs#mafsaustralia#reality#realitytv#realitytvshows

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Tumblr has really empowered people whose voices are otherwise marginalized and given them a place to find their community

Amanda Brennan in Allison McCracken, Chapter 3 ‘Going Down the Rabbit Hole’

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tumblr: a digital community? (Week 3)

Traditionally introduced by Jurgen Habermas, the ‘public sphere’ is a concept used to explain social relationships within the “structure” (Bruns et al. 2016, p. 99) of media. Subsequent to this notion has been a discussion of digital communities. A digital community is a “distinct, bounded group” (Keller 2019, p. 2) of “social relationships” (Keller 2019, p. 2) within an “online space” (Keller 2019, p. 2) that is “accessible” to everyone (Kruse 2018).

Tumblr functions as a blogging space. The anonymity of Tumblr profiles (McCracken 2020, p. 39), coupled with its features of hiding follower counts and “blue check marks” (McCracken 2020, p. 39) (indicating official accounts) means that Tumblr promotes an authentic and accessible social media experience for its users (McCracken 2020, p. 39).

Tumblr is well-known to fan communities and fandoms. Tumblr makes interactions between fans easier through its use of hashtags (McCracken 2020, p. 41). Hashtags allow users to “search” (McCracken 2020, p. 41) and be “introduced” (McCracken 2020, p. 41) to others within the fandom thus promoting “social relationships” (Keller 2019, p. 2). Moreover, Tumblr’s use of “GIF sets” (McCracken 2020, p. 43) allows fans to interact through visual means. Through these processes, Tumblr has created a specific means by which its users can connect and interact, creating social relationships and discussions.

Tumblr promotes a safe space for all its users (McCracken 2020, p. 40). Tumblr is utilised by the LGBTQ + community due to its anonymity and known accepting presence. Additionally, young feminists utilize Tumblr to communicate and interact away from judgement (Keller 2020, p. 1). This accessibility has also aided Tumblr in facilitating important and impactful events for different digital communities. Ultimately, Tumblr’s anonymity has “empowered” (McCracken 2020, p. 40) users who would be “otherwise marginalised” (McCracken 2020, p. 40) to use their voices and “find their community” (McCracken 2020, p. 40). Hence, Tumblr acts as a digital community through its ability to connect users to different communities to facilitate discussion and foster social relationships.

References:

Allison McCracken, Chapter 3 ‘Going Down the Rabbit Hole: An Interview with Amanda Brennan, Head of Content Insights and Social, Tumblr’ in a tumblr book: platform and cultures eds Allison McCracken, Alexander Cho, Louisa Stein, and Indira Neill Hoch (University of Michigan Press: 2020) https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11537055

Bruns, A & Highfield, T 2016 Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere. In A Bruns, G Enli, E Skogerbø, AO Larsson, & Christensen, C (Eds.) The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge, New York, pp. 56-73

Jessalynn Keller, “Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms , Social Media + Society Volume: 5 issue: 3, 2019.

#digitaldiscussion#digitalcommunities#digital#social media#social media activitism#tumblr#feminism#youngfeminist#mda20009#public sphere#fandom

2 notes

·

View notes