I babble about them and you hit the like button. I am a paleontologist and want to share my love of the past! Feel free to ask questions or suggest a species to cover.

Last active 3 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

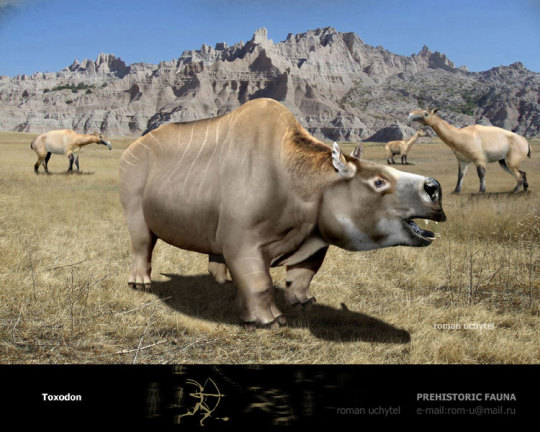

Toxodon

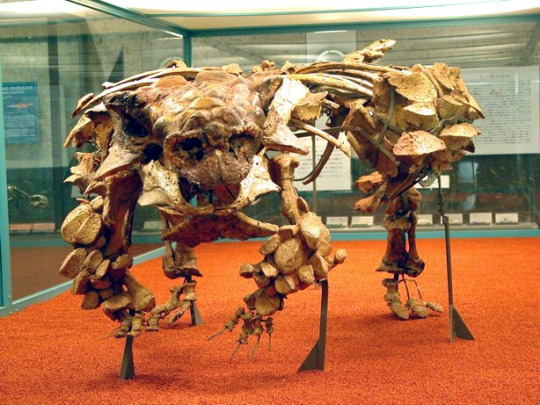

Mounted specimen on display at Harvard Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Roman Uchytel

When: Pleistocene (~2.6 million to 16,000 years ago)

Where: South America

What: Toxodon is another one of the large herbivorous animals that roamed over South America. Charles Darwin purchased the skull of the first Toxodon known to the Old World during his journey on the Beagle. This skull was sent back to England were Sir Richard Own described it and named the animal Toxodon - 'bow teeth' based on the curving nature of its gigantic molars. Soon complete skeletons of this amazing animal were known. The first interpratations reconstructed Toxodon as a semi-aquatic animal, much like the modern hippo, but later studies of the limbs and teeth of speciemens show this was incorrect. Toxodon was more the analogue of today's rhinos than a hippo, a fully terrestrial animal with teeth well adapted for grinding tough plants in somewhat arid environments. Some Toxodon specimens have been found associated with arrowheads, showing that the first people to emigrate into South America had contact with these animals, and appear to have hunted them.

Where does Toxodon fit into the tree of life? Like its contemporary Macrauchenia (which you can see in the background of the reconstruction), its relationship to living mammals is uncertain. It falls into the larger clade of Notoungulata, literally Southern Ungulates, but the placment of this group within placental mammals is highly uncertain. They maybe have a close relationship with animals in the group Afrotheria but research in mammalian systematics is only beginning to be able to evaluate that, and other hypotheses. So what is Toxodon? We just don't know.

#cenozoic#pleistocene#south america#mammal#eutheria#placental#maybe?#geology#biology#science#fossil#paleontology

147 notes

·

View notes

Photo

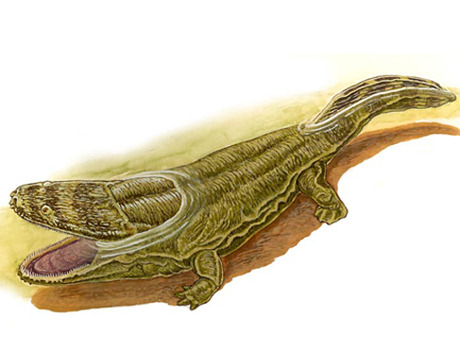

Koskinonodon formerly known as Buettneria

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Matt Celeskey

When: Triassic (~228 - 216 million years ago)

Where: North America

What: Koskinonodon is one of the later surviving of the giant amphibians. This beast could read up to 10 feet (~ 3 meters) long and was very common in the ancient American southwest. Koskinonodon was known by the name Buettneria for over 80 years, until a long standing nomenclature problem was resovled. See, the name Buettneria was applied to this animal in honor of W. H. Buettner, a fossil collector in the first part of the 20th century. This was in 1922, however, a living species of katydid was given the genus name of Buettneria decades earlier in 1889. Thus the name was not actually availble to be used for this giant amphibian. The name Koskinonodon was applied in 2007. This name was used because a specimen that was named Koskinonodon in 1929 was later determined to belong to the same genus as the previously known specimens that were then called Buettneria. When a genus is renamed this is typically how it is done, you comb though the past literature and use the oldest available name that has ever been used for any species (or specimens!) now housed in that genus. Sadly sometimes you end up using names that are just not as cool as the original. Sorry W. H. Buettner. At least your namesake fossil lives on in outdated museum exhibits. ;)

Koskinonodon is closely related to another large amphibian I have posted, Metoposaurus. It is likely that these two animals occupied the same habitates in life. What differentiates them? At just the general morphology level Koskinonodon has a much longer skull, a longer tail, and less robust limbs. It is common that when a paleo environment is reconstructed just one example of each 'type' of animal is used, but this is not really realistic. Think about the average North American forest today. Multiple species of all sorts of 'types' of animals are found there, multiple squirrels, deers, and birds that resemble each other very closely but are distinct species. This is how it was in the Mesozoic world as well!

#triassic#mesozoic#geology#biology#evolution#fossils#paleontology#science#amphibian#North America#giant#butt

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

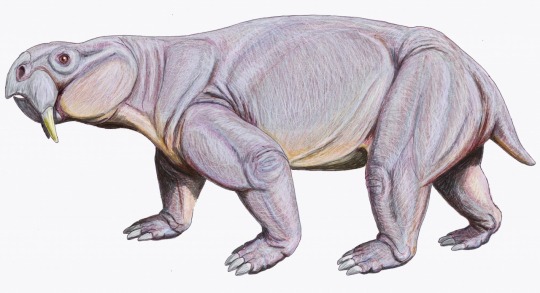

Dinodontosaurus

Mounted specimen on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Dmitry Bogdanov

When: Triassic (242 - 230 million years ago)

Where: Worldwide

What: Dinodontosaurus is a synapsid, or 'mammal like reptile'. It was one of the most common large herbivorous animals in the mid Triassic. These beasts reached lengths of 8 feet (2.4 meters) and are estimated to have weighed hundres of pounds. They fall within the clade Dicynodontia, so named for their two large front teeth. A fossil find in Brazil of over 10 Dinodontosaurus, including juveniles, shows these animals lived in herds and cared for their young.

Synapsids were extremtly common in the Permian, but were hit hard by the end Permian extinction. Some groups, such as the Dicynodonts exemplified by Dinodontosaurus, however, made it though the extinction just fine. The extinction at the end of the Triassic period, however, was brutal to this clade, wiping out the vast majority of species. Some dicynodonts made it though this extinction, but the clade continued to dwindle throughout the rest of the Mesozoic, with the last dicynodont vanishing in the mid Cretaceous. In the synapsid family tree dicynodonts are fairly far up there, falling far closer to gorgonopsids than to the basal "pelycosaurs".

#triassic#south america#europe#synapsid#paleontology#geology#fossil#biology#evolution#science#Mesozoic

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gemuendina

Fossil and model both on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Model created by Louis Ferraglio

When: Early Devonian (~410 to 392 million years ago)

Where: Germany

What: Gemuendina is an odd little placoderm fish. It is known only from the early Devonian of Germany, from deposits that have been reconstructed to represent areas with anoxic bottom waters. Anoxic means 'lack of oxygen', so there was no oxygen in the sediments where the dead or dying fish fell, and thus scavengers and decomposing organisms could not disturb the remains. Specimens of Gemuendina have only been preserved in such conditions because their armor was not a solid shield, as seen in some other placoderms, but rather a series of unfused relatively thin bony plates. This placoderm bears a close resemblance to a ray, with its flat body and series of horizontal fins. This is another excellent example of convergent evolution. Unlike rays, however, the eyes of Gemuendina were on the top of its head, not the side, and its nostrils were on top as well, not on its ventral (under) surface.

Within Placodermi Gemuendina falls into the clade Rhenanida. This group shares the characters of a ray-like body and the lose series of unfused plates that covered their flat bodies. While the ray-like body is a shared derived feature that unites the group, the seires of individual plates is likely a retained primitive feature that was also found in the first placoderms, which gave rise to all of the rest, including massive forms such as Dunkleosteus. Gemuendina is one of the earliest well-known members of the clade, but isolated plates from tens of millions of years earlier in the Silurian period may represent the true first rhenanids. Though the fossils are rare and fragmentary, rhenanids swam throughout the Devonian waters all over the world.

#devonian#europe#germany#paleontology#geology#paleozoic#fossil#biology#fish#evolution#science#placoderm

160 notes

·

View notes

Link

Heritage Auctions had their big center piece auction anyway, basically ignoring the courts. Its a conditional sale, so at least the buyer, whoever it is, can't disappear with the specimen right away.

Press release from the link above:

Tyrannosaurus Brings $1,052,500 At Heritage Auctions New York

Conditional Sale of Tyrannosaurus bataar, 8-feet high and 24-feet long, will be contingent upon resolution of a court proceeding.

NEW YORK – One of the great dinosaurs of the Cretaceous era, an eight-foot tall, 24-foot long, 75% complete Tyrannosaurus bataar – the slightly smaller Asian counterpart to the legendary North American T-Rex – has sold for $1,052,500, contingent upon resolution of a Texas state court proceeding. Heritage Auctions sold this dinosaur on May 20 as part of the company’s Natural History auction at Center 548 (548 W. 22nd Street, between 10th Ave. and West Street). The entire auction realized $2.63 million, not counting post-auction sales, which are still in progress.

“This is a once in a generation dinosaur and collectors definitely responded to both its rarity and its fierce beauty,” said David Herskowitz, Director of Natural History at Heritage Auctions. “A dino like this is rare to come across in any condition, let alone one as pristine as this.”

The sale – marking the first time a fully prepared Tyrannosaur has been made available at public auction (“Sue” the T-Rex was sold in 1996, but was still in field jackets) – was not without controversy, as the Mongolian government released a statement 48 hours before the auction suggesting the fossil belonged to the country.

“We respect the various opinions on the subject and wish to protect the legal rights of all parties involved,” said Greg Rohan, President of Heritage Auctions. “We have legal assurances from our reputable consignors that the specimen was obtained legally. As far as we know, the Mongolian government has not produced any evidence that the piece originated in its territory, but the final determination will be up to the American legal system.”

The proceedings were not without event, however, as Mongolia’s Texas-based attorney, without authority from the New York judicial system, tried to interrupt the auction.

The Tyrannosaurus bataar roamed what is now Central Asia in the Cretaceous period, around 80 million years ago. The dino had been in storage in England, still in its field jackets, until it was brought to the United States last year.

I really do not like these people.

I will let you all know if there are any more updates.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why private collecting is bad.

A statement about fossil material in private hands

Today's fossil (March 20th) was chosen to be the one highlighted due to the auction going on in NYC that I posted about yesterday. The Tarbosaurus skeleton is the most impressive of the pillaged paleontological prizes, but there is more Mongolian material slated to go up for auction than just this skeleton. In happy news the Tarbosaurus skeleton at least is not going up for auction today, thanks to a restraining order issued by a US Judge, but I am uncertain if this impacts the rest of the stolen material. There is still an online petition protesting the sale of these fossils, which covers all the material, not just the theropod skeleton.

I want to talk for a minute about why it is such a tragedy that auctions like this still occur. Let us examine the skull said to be a Saichania specimen. This dinosaur is /only/ known from Mongolia. Currently at least. Thus it is very likely this skull is from Mongolia, but if it was not and did represent an occurrence of Saichania outside of its previous range? That would be extremely important. It would expand the geographic range of the species and possibly its temporal range as well. So this is a skull that should be in a museum (yes, we do say this) and studied, no matter its providence.

Locality information is a huge problem with private collections and reselling of this material. Museums take great care to record every single detail about where a specimen was collected. For a fossil this would mean exact geographic location, the rock unit it was found in down to precise detail, and if this specimen was likely collected in place or if there was some transportation previous to its discovery. At the bare minimum. You can write pages of field notes about a single specimen, and the collector's name is also part of the accession information. I personally have dug though 100+ year old field notes in order to solve mysteries such as: "Is it possible all these bones do not belong to the same specimen?" or "Do these two different specimen numbers actually represent a single individual?". You typically have none of this with private collecting. The locality information is sometimes nothing more than the country or state it came from. Yes, you can have more and there /are/ some private collectors out there who keep geologists on staff (or are geologists themselves) and this precious information is not lost. But that is by far the exception, and if the material is resold over and over again, each transition of ownership introduces another stage at which the specimen can be separated forever from its locality information.

So if we don't have this information as to providence, so what? Who cares? What does it matter? It matters a great deal. You can have the most spectacular skull in the world, but if you do not know when and where it came from it can tell you hardly anything about the evolutionary history of the group it belongs to. You describe it and put it in an analysis and great, okay, so at one point somewhere on earth at sometime an animal looked like this and was related to these other animals. You don't know the kind of environment the specimen was in, if it was found far from its close relatives, if it was occurring at the same time as the rest of the clade... Nothing. Anatomy and relationships are just the start of the study of evolution of a lineage, you need the time and geographic component to understand any of the really interesting and important parts of the story.

The above didn't even touch on how terrible it is when the specimens are not even owned by individuals in their native country. I may really dislike it if say, a rancher in Wyoming finds a crocodile skull and sells it to the highest bidder, but that pales next to what is happening with these mongolian fossils.

#paleontology#fossil#geology#science#ethics#education#wordswordswords#biology#fossils#private collecting#dinosaurs#dinos#important

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saichania

Mounted specimen on display at Dinosaur Kingdom, in Nakasato, Japan

Reconstruction by Andrey Atuchin

When: Late Cretaceous (~83 to 70 million years ago)

Where: Mongolia

What: Saichania was an armored plant eating dinosaur that roamed the deserts of Mongolia in the late Cretaceous. It was about 22 ft (~6 meters) long and heavily built. It was more fearsome looking than most armored dinosaurs as it did not just have flat armor plates on its body, but rather was covered with spikes. These dinosaurs were armored all over, there is even evidence of armored eyelids! This suit of armor would have protected Saichania from predators in the late Mesozoic mongolian desert. Fossils are typically found in deserts and badlands worldwide, but typically these areas were very different environments when the species represented by the fossils were alive. The ancient Gobi Desert was much closer to the harsh modern environment than most. Saichania was well adapted for desert life, with its stocky body and teeth designed for grinding the toughest of the desert plants.

Saichania falls within Ankylosauridae, a group of armored dinosaurs found almost worldwide. It is one of the last and most derived of the ankylosaurids. One good way to differentiate the deserved ankylosaurids from their armored close relatives is the presence of a tail club. Saichania did not have the most massive club known, but it was still a significant feature. Ankylosaurids were one of the dinosaur groups that made it right up to the end of the Cretaceous period, vanishing with the rest of the non-avian dinosaurs.

#Mongolia#dinosaur#archosauria#cretaceous#Mesozoic#paleontology#geology#biology#evolution#science#fossil#armored

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

Information about the "T-rex" skeleton being auctioned in NYC

Statement from the President of Mongolia

As some of you might have seen in the media, there is going to be an auction in New York City tomorrow, May 20th 2012. Heritage Auctions is the auction house running the event. The biggest ticket item, and the one that is getting this auction a lot of coverage in the press, is an almost complete skeleton of Tarbosaurus bataar, which is being referred to as a T-rex in some stories. The two dinosaurs are very simular to one another. The problem is that this specimen assuredly comes from Mongolia. Thus, it is stolen.

Here is a letter from Dr. Mark Norell, the dinosaur curator at the American Museum of Natural History, explaining the situation:

It is with great concern that I see Mongolian dinosaur materials listed in the upcoming (May 20) Heritage Auctions Natural History catalogue. For the last 22 years I have excavated specimens Mongolia in conjunction with the Mongolian Academy of Sciences. I have been an author on over 75 scientific papers describing these important specimens. Unfortunately, in my years in the desert I have witnessed ever increasing illegal looting of dinosaur sites, including some of my own excavations. These extremely important fossils are now appearing on the international market. In the current catalogue Lot 49317 (a skull of Saichania) and Lot 49315 (a mounted Tarbosaurus skeleton) clearly were excavated in Mongolia as this is the only locality in the world where these dinosaurs are known. The copy listed in the catalogue, while not mentioning Mongolia specifically (the locality is listed as Central Asia) repeatedly makes reference to the Gobi Desert and to the fact that other specimens of dinosaurs were collected in Mongolia. As someone who is intimately familiar with these faunas, these specimens were undoubtedly looted from Mongolia. There is no legal mechanism (nor has there been for over 50 years) to remove vertebrate fossil material from Mongolia. These specimens are the patrimony of the Mongolian people and should be in a museum in Mongolia. As a professional paleontologist, am appalled that these illegally collected specimens (with no associated documents regarding provenance) are being are being sold at auction.

Sincerely,

Dr. Mark A. Norell

Chairman and Curator

Division of Paleontology

So far the only response from the auction house has been 'we didn't break any US laws, why didn't the Mongolian government contact us before?' and my favorite, and I will quote here: Mongolia won its independence in 1921 and this specimen is obviously quite a bit older than that.

What can be done? Probably not much, sadly. But it is important that people realize it is /NOT/ okay to take these materials out of their countries of origin with out working with the local governments. That is true for both for profit enterprises such as this auction but also for purely scientific studies. Most of the mongolian material at the AMNH currently is on long term loans, and many amazing specimens have already been returned to Mongolia.

It is very upsetting that the vast majority of articles in the media about this specimen and the auction make NO mention of the illegal source of the material. Spread the word! And please, never buy vertebrate fossils from private collectors.

258 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Teleoceras

Mounted specimen on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Roman Uchytel

When: Miocene and Pliocene (~17.5 - 4.5 million years ago, and maybe a couple million years more!)

Where: North America

What: Teleoceras was an aquatic rhinoceros. It was a very common beast in the North American Miocene. Yes, rhinos in North America! I have been eager to share with you all the amazing diversity of North American rhinos. The discovery of a tremendous amount of rhinos, not just in terms of numbers of species but their diversity, is one of the great surprises of North American paleontological expeditions in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This continent was home to rhinos the size of modern pigs, rhinos that could run quickly, and even aquatic rhinos! Teleoceras is one of these aquatic rhinos.

Teleoceras had very short legs for a rhino and a nubby horn. This horn is actually pretty large in the scheme of things. As much as the modern rhinos are famous for their horns the vast majority of fossil rhinos show no evidence of having a horn. We can tell this via the presence or lack of a rough surface on the nasal bones. In life Teleoceras would have probably occupied a niche very simular to the modern hippopotamus.

#cenozoic#north america#Miocene#perissodactyla#rhino#paleontology#geology#evolution#mammal#biology#science#ungulate#animal

150 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tiktaalik - the fishapod

Model by Tyler Keillor and this particular set up on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

When: Late Devonian (~375 million years ago)

Where: Found on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada

What: Tiktaalik is a very critical specimen on the line of tetrapod evolution. In the tetrapod family tree it falls between sarcopterygians ('lobed fin' fish) that looked much like the living Coelacanth and more advanced tetrapods, such as Acanthostega. The discovery and announcement of Tiktaalik was very exciting, as fossils on both side of transitional period were known for a long time, but nothing really in the middle. Of course as with the discovery of any 'missing link' now we have two more 'links missing': one on either side of Tiktaalik ;). The most important part of the specimen is the anatomy of its forelimb - there was a well developed wrist inside the fin of Tiktaalik! Not only that, but it possibly has the first 'fingers' seen in the tetrapod lineage. Unfortunately the back end of Tiktaalik is unknown... for now!

In life Tiktaalik would have been an aquatic animal, as its limbs could not support its weight on land - but they would have been very helpful for maneuvering the creature around the shallow waters of prehistoric Canada. Based on the spiracles - openings behind the eyes- of the skull it has been preposed Tiktaalik could have had a form of primitive lung.

If you want to know more about Tiktaalik - check out its website at: http://tiktaalik.uchicago.edu/. And for more in depth reading, I cannot recommend the book 'Your Inner Fish', written by the discover of Tiktaalik - Neil Shubin, enough! It is a really great explanation of how Tiktaalik fits into the evolution of tetrapods and explaining homology in general! Shubin has done a fantastic job of promoting public science education using this great Tiktaalik specimen as a starting point.

Just look at all of these models getting ready to go out to museums. Maybe one is near you!

#devonian#paleozoic#paleontology#fossil#geology#biology#evolution#science#north america#canada#tetrapoda#tetrapod#transitional fossil#fish got legs!!!

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hybodus

Fossil specimen from the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany

Model by Dan Erickson and on display at the American Museum of Natural History

When: Permian to Cretaceous (260 to 80 million years ago)

Where: World Wide

What: Hybodus is a very wide spread, both temporally and geographically, fossil shark. I will be upfront here and say that I may be grossly over representing its temporal range, the literature is rather confusing and there have been a number of species going in and out of Hybodus over the years. So you may want to consider this an article on hybodontiform sharks in general, rather than just the one genus. Shark fossils are fairly rare in the fossil record when compared to other fish because sharks do not ossified their skeleton. However, Hybodus and its kin can be identified from fragmentary remains by their distintive teeth (two kinds in their jaws, both flat and pointy) and their ossified dorsal spines. These spines can be easily seen on both the fossil and the model above, they were most likely involved with stabilization of Hybodus as it swam. The relatively few full body specimens preserved complete the picture, showing us that Hybodus was a streamlined shark with a very heavy ribcage compared to most sharks, and that the males had not only ventral claspers, as seen in modern sharks, but also a series of spines on the side of the head - which are depicted above.

Hybodontiform sharks were the dominate group of sharks in the Jurassic period, and were even very common in the late Cretaceous after modern sharks had originated and diversified. Studies of this archaic shark clade have shown they were most likely over all slow swimmers, but they could enjoy brief bursts of speed if needed. The diverse teeth forms of hybodont sharks imply they did not just eat fish, but also were able to prey on hard shelled invertebrates. In the shark family tree Hybodontiformes is the first group outside of Neoselachii - the clade that contains all living sharks and rays.

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rutiodon

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Model on display at Dinosaur State Park, Connecticut

When: Late Triassic (~ 230 to 204 million years ago)

Where: North America

What: Rutiodon is a phytosaur. We have looked at another phytosaur before, Redondasaurus, which was one of the biggest and most derived of the phytosaurs. Rutiodon falls on the other end of the phytosaur family tree. Rutidon was about half (~25 feet/7.5 meters) as long as Redondasaurus, but as it was built so much more slenderly, it is more accurate to say it is only 1/3rd or even 1/4th the size of its gigantic relative. This different body construction naturally translated into a different mode of life in Rutidon. Notice how slender and long its snout is? Some modern crocodiles have this same style of snout and they are predominately fish eaters, thus it is likely that Rutidon was as well, and it did not prey on terrestrial vertebrates.

Phytosaurs strongly resemble modern crocodiles in other ways, and Rutiodon looks even more like a crocodile than many others of its kin. But this animal is most assuradly a phytosaur, /not/ a crocodile. One easy way to tell is if you look at the front end of its snout, look how the upper jaw is bent? That is a clear phytosaur feature. Another thing to look for is the position of the nose holes. Rutiodon has the phytosaur position of back near the top of its skull - whereas crocodiles have them in the more typically place at the end of the snout.

Minor side trivia about this particular specimen of Rutiodon. It is number FR:AMNH 1, this means it was the first specimen to be catalogue into the fossil reptile collection. This specimen comes from a coal mine in Chatham County, North Carolina, and was collected by the famous paleontologist William Diller Matthew in 1895.

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

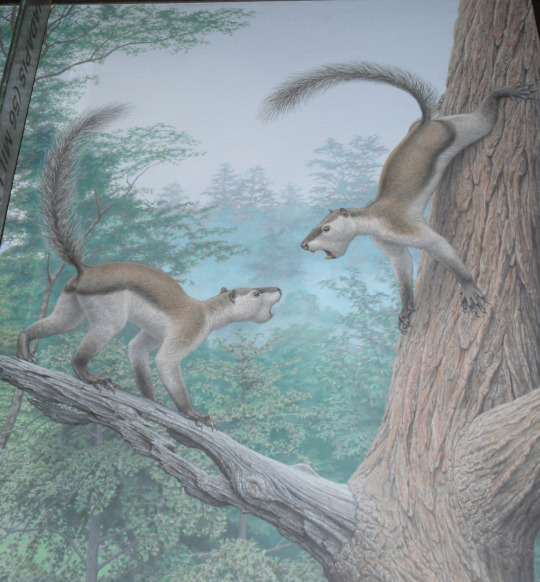

Plesiadapis

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Reconstruction by Jay Matternes

When: Late Paleocene to Early Eocene (~ 61 - 55 millon years ago)

Where: North America and Europe

What: Plesiadapis is a small tree-dwelling mammal that was fairly comment in the late Paleocene of North America and Europe. This ancient mammalian taxon was about the size of a house cat, and though it may look very reminiscent of a squirrel it is a member of the primate family, as part of the larger group Plesiadapiformes. The latest research has shown that Plesiadapis was actually atypical for its namesake clade; this genus tended to be much larger than the average plesiadapiform and was not as well adapted for climbing as its smaller relatives, lacking a hand specially adapted for grasping. Plesiadapis could climb trees, but it would have been an arboreal quadruped, like the living squirrels, rather than a grasping locmotion as seen in most primates today. Another features reminiscent of rodents in Plesiadapis (and this is found in most of its kin) is its enlarged front teeth and the reduction or loss of teeth between these massive incisors and the grinding cheek teeth. Plesiadapis has been reconstructed as a frugivore - meaning its diet was primarily comprised of fruit. As much of North America and Europe was covered with lush sub-tropical forests during its range, Plesiadapis would have had quite a large selection of fruits to feed on.

The placement of Plesiadapiformes has been somewhat controversial in the past decade or so. There is uniform agreement that these animals fall somewhere near the group Euarchonta within placental mammals, but exactly where has been much debated. Euarchonta contains not only primates, but also the Scandentia (tree shrews) and Dermoptera (flying lemurs). Some early studies placed plesiadapiforms closer to the dermopterans than primates, but more recent studies tend to find this clade as either the first branches to spring off the primate lineage or just outside of Euarchonta itself, as stem taxa to all three orders. One last point to make things even more confusing! The group Plesiadapiformes? It is probably not a monophyletic (natural) group in reality. It is looking more and more like that some taxa previously grouped within Plesiadapiformes fall closer to living primates than to other taxa within the group.

To sum up that confusing mess, Plesiadapiformes are very important in understanding primate evolution, as at least some members of this assemblage of taxa are the first animals on the primate lineage. As this lineage includes me and you there is a lot of study focused on this group right now! Nice to see animals that are primarily paleocene taxa finally getting some attention.

#mammal#primate#north america#europe#fossil#paleontology#geology#evolution#placental#cenozoic#eocene#science#paleozoic

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almost back but not just yet!!

However I think a number of you would be interested in this

Live Chat with Museum Paleontologists Tomorrow ( 5-10-12) at 1 pm Eastern

Were dinosaurs already undergoing a long-term decline before an asteroid hit at the end of the Cretaceous? Join Museum scientists Steve Brusatte and Mark Norell for a discussion and Q&A session moderated by Wired Science Associate Editor Brandon Keim about their recent findings that illuminate the state of several dinosaur groups around the time of the mass extinction 65.5 million years ago.

The event will take place tomorrow in Linder Theater and will also be streamed live at amnh.org/live. If you can't make it to Linder Theater, join the conversation by submitting questions to [email protected] or via Twitter using the hashtag #AMNHLive.

To learn more about this study, watch an interview with Steve Brusatte and Mark Norell on amnh.org/news.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today I spent the morning working in Mammalogy here. I snapped a couple of quick pictures of one of my favorite things that lurk in the hallways.

The pygmy dog!

I included the first picture for a sense of scale, this thing is tiny! Supposedly it was a fully grown adult dog. Is it real? Nobody really knows. This is one of those objects that just have been in the museum forever and its original history is unknown. But either way it is adorable. Look at those tiny claws!

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Where I was today instead of writing an entry for you! ;)

This is the CT scanner at the American Museum of Natural History. It is a fickle beast. Hence the dunce cap upon the top of the machine. Putting specimens in here and bombarding them with X-rays gives us a digital image of the object, such as the elephant skull I linked yesterday.

The close up view shows a specimen in the midst of being scanned.

Busy busy busy!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

And the answer is...

This is an endocast of a mammoth!

An endocast is what you get when material infills the skull, filling up the space where the brain was housed in life. Natural endocasts are often formed when a skull is filled in by sediment and then over time the skull is damaged or even destroyed as it chips away bit by bit, but the endocast remains. There are some great specimens out there where just the brain case has been damaged, but much of the rest of the skull remains.

An endocast is not a perfect replica of the brain. It just shows the area that held the brain, but any folds or grooves on the surface of the brain that did not leave and impression in the inner skull wall will not be preserved on the endocast.

The mammoth endocasts above are made from plaster, and were created by workers at the American Museum of Natural History decades ago. Now they didn't pour the plaster right into the skull and then pull it out by magic. First a latex mold was made by pouring this material into the skull, waiting until it dried, and then pulling it out. This mold can then be used to create endocasts by filling it with plaster and once they dry peel off the mold again. It doesn't create a fantastic endocast... but it is something!

You may be thinking these endocasts seem rather small for a mammoth. Check this out

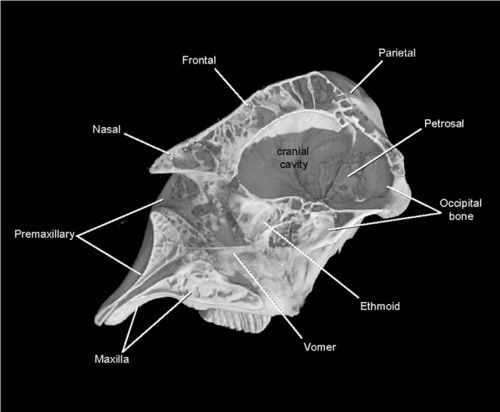

That is a sagittal (down the midline) section of an asian elephant skull, taken from digimorph. This is a CT scan,no skulls were harmed in the making of this image. ;) The brains of proboscidians don't take up as much of the skull as most other mammals, due to how the skull has transformed to accommodate the muscles of that huge trunk.

So how did you guys do in your answers? Lots of you got that it was some sort of brain, good job!!

jupiterorbust successfully ID'ed it as a mammoth brain, great job!

Honorable mention to

vfeynmanv for a great post showing how you went about trying to figure it out, I really enjoyed reading that. And you were pretty close!

22 notes

·

View notes