Asia-Pacific Reporting provides breaking news and original commentary on diplomacy, defense, culture, and trade issues in the Asia-Pacific and Arctic from leading journalists, think tank experts, and policy wonks in the region.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

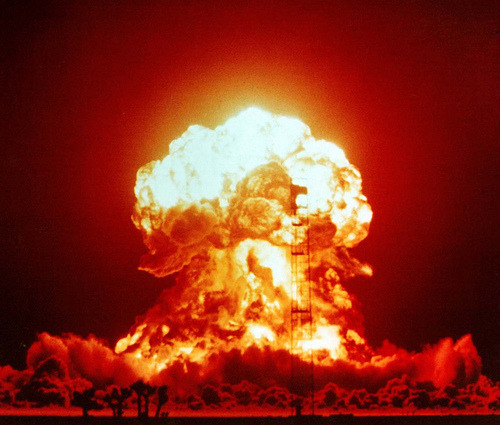

NATO Needs Soul Searching on Emerging Technologies

At present, the world is witnessing an unprecedented period of scientific and technological innovation being spurred on by the synergistic combination of converging technologies, including nanotechnology, biotechnology, robotics, information technology, and cognitive science (NBRIC). Such convergence is producing a wide range of disruptive innovations that may contribute to a "tremendous improvement in human abilities, societal outcomes, the nation's productivity, and the quality of life". And, current WMD states clearly do not possess a monopoly over such innovation.

Converging technologies also pose fundamental human security challenges. As Francis Fukuyama once argued in Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution, converging technologies could inequitably transform the world we live in and, in the process, undermine the very foundations that underpin liberal democracies. Whether or not such a future unfolds, it is clear that their application raises serious ethical and moral issues that are proving divisive for allies and enemies alike (eg: the debates over armed drones and cyber espionage). Even where common approaches can be achieved (eg: combatting designer drugs), converging technologies are growing "faster than our ability to legislate or regulate" them.

These developments are putting new stresses on the NATO alliance. According to a recent experts workshop, the NBRIC Revolution is threatening NATO unity. "As warfare is outsourced to only those who are 'near peers' in technology and societal views shift," NATO will likely experience "decreasing political tolerance for alliance security efforts". If NATO member states want to sustain "the traditional transatlantic compact [European political support in return for US military guarantees]", they must change the way NATO approaches cooperative security around emerging technologies. And, they need to do it now.

Read full story on Al Jazeera English: "NATO Risks Unity Over Emerging Technologies Divide."

Image Credit: The Official CTBTO Photostream via Flickr Creative Commons

#nato#eucom#PACOM#Southcom#centcom#northcom#foreign affairs#foreign policy#diplomacy#pentagon#national security#state department#auspol#dfat#defence#nuclear#cybersecurity#biotechnology#nanotechnology#robotics#cognitive

0 notes

Text

Shared Values Driving Ever Stronger U.S.-NZ Partnership

In a speech given on Monday to the Pacific Islands Society at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), the Acting New Zealand High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Mr. Rob Taylor, argued that shared values, not just shared interests, are driving the renewed strategic partnership between the United States and New Zealand.

According to Mr. Taylor, the 2010 Wellington Declaration provided a "key turning point in United States-New Zealand relations" that has enabled both countries "to move beyond policy differences that emerged in the mid-1980s" and instead "focus on the future with emphasis on areas of cooperation."

More than two years later, Mr. Taylor believes that the U.S.-NZ strategic partnership has moved into high gear with both Wellington and Washington confident that this period of renewed cooperation "will endure."

So, can the strategic partnership get any stronger? The High Commissioner's talk certainly gave the impression that it can -- especially if the Obama Administration follows through on its much hyped Asia pivot.

Looking ahead, Mr. Taylor stresses that "on-going and future cooperation between the two nations" will place "particular emphasis on the South Pacific." This includes investing further in joint initiatives in the region, such as renewable energy, disaster response, climate change adaptation, and enhanced dialogue on regional security.

South Pacific fisheries will be an area of particular focus. Mr. Taylor says that his country will be working with the United States "to enhance Pacific capability to catch and process more of their own fisheries resources" and with the United States, Australia, and France to "to provide maritime surveillance of Pacific Island states, in particular their Exclusive Economic Zones. "

These efforts will seek to prevent the collapse of one of the world's most important natural resources. As an analyst with the Pacific Partnerships Initiative at CSIS recently pointed out, Pacific fisheries now account for more than 50 percent of the global marine catch and represent the "largest economic interest shared by the United States and the Pacific Islands." So, in this case, shared interests and shared values appear to be driving US-NZ cooperation.

#new zealand#anzus#pacom#soas#university of london#lse#war studies#strategic artnership#united states#pacific islands

0 notes

Text

Google in North Korea: Pyongyang Kowtow or Smart Diplomacy?

When Google’s executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, and former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson headed to the DPRK in early January they certainly turned some heads.

Many viewed their trip as undermining Western efforts to secure stronger sanctions, following North Korea’s ballistic missile launch in December 2012. They have also been criticised for providing Kim Jong-un with an opportunity to ‘convey a sense of legitimacy and international recognition and acceptance’ to his people. With a nuclear test apparently looming over the horizon, why did Schmidt and Richardson make this visit?

It is hard to imagine that Schmidt was there to seize on the North’s unrealised market potential. Although some speculate that the DPRK may be ready to change its approach regarding free use of the internet, there is scant evidence to support this claim. From the US perspective, one obvious reason for the visit was to secure the release of an American detainee, Kenneth Bae, arrested while escorting tourists in late 2012 for allegedly possessing banned electronic devices. This explanation makes sense, as it fits with the regime’s traditional pattern of behaviour.

While there have been glimmers of hope that Kim Jong-un might move away from his father’s isolationist tendencies, experience tells us to be sceptical. Even though new power dynamics appear to be at play within the Kim Jong-un regime, only minor modifications have been made. The ways in which his government leverages international insecurity to achieve political objectives — through missile launches, arms proliferation and nuclear tests — continue to maintain the status quo set by his father, Kim Jong-il.

One only needs to look back to 2009 when Kim Jong-il used another set of detainees to force a visit by former US president Bill Clinton. In that case two American journalists, Euna Lee and Lora Ling, had been caught illegally entering the North without a visa, but were released during Clinton’s visit. While the details of Bae’s case differ, his detention nevertheless illustrates North Korea’s similar use of detention to elicit a high-level ‘private humanitarian’ mission response.

One can understand why US power brokers concluded that the visit, which the US government could (and did) publicly disavow, was necessary. Although the visit rewarded North Korea for using Bae as a pawn in its strategic game of chess with the United States, it secured Bae’s freedom. While this sets a bad precedent for King Jong-un, if history repeats itself, Bae should be released sometime in 2013.

But this raises an important follow-on question: who is really in the driver’s seat in US–DPRK relations? If the DPRK can effectively coerce the United States so easily, what hope is there that the United States can stop North Korea from further developing its nuclear and cyber programs? This is an important point and one that continues to divide policy experts in Washington. President Obama has made it clear that he is ‘not afraid of losing the PR war to dictators’. Yet others may see the US administration’s ‘concession’ as a tragic form of nuclear accommodation.

Either way, it is naïve to think that the visit was just a trade-off between a detainee and some small recognition of North Korean power and prestige. The trip also provided an excellent opportunity for Kim Jong-un to be heard. If the DPRK wants to return to the negotiating table, then perhaps this is their preferred approach. Since the United States probably shares that desire, the detainee episode might just serve as a bizarre trigger for such re-engagement.

If the DPRK is moving toward another nuclear test, as some have suggested, then the region is facing yet another escalation. Getting the DPRK back to the table before it crosses the line and conducts the test probably is, at least in the minds of many in the Obama administration, worth the cost of the detainee drama.

The question now is what if this approach fails? For example, what if Bae is not released and the DPRK either avoids harsh sanctions or conducts another nuclear test?

Despite these risks, the trip also provided an opportunity for Schmidt and Jared Cohen, director of Google Ideas, a rare real-world opportunity to engage the Kim Jong-un regime. If Schmidt and Cohen now come out and hammer North Korea on internet freedom, cyber security and general economic backwardness, they can do so from experience, increasing their persuasiveness with both foreign and domestic audiences. They may also have gleaned some valuable new insights into how to advance US national security objectives.

Kim Jong-un has certainly gained the most from the Google delegation visit up to this point. But in the long term, it remains unclear who the visit most advantaged. In the current climate, it is possible that President Obama will find it more difficult to obtain China’s support on North Korean proliferation during his second term in office. So the United States may be willing to wager more to court North Korea in the year ahead, hoping that Kim Jong-un follows Myanmar’s lead. While this may ultimately be wishful thinking, one could argue that it is worth the risk when considering the perceived lack of alternatives.

An earlier version of this article appeared here on the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s website and here on the East Asia Forum.

#north korea#dprk#obama administration#google#eric schmidt#kim jong-un#kim jong-il#china#united states

1 note

·

View note

Text

Facebook: The New Weapon in Counter-Proliferation?

How should the American and British governments utilise the internet in combating WMD development and proliferation? Will the pursuit of one of these foreign policy objectives inevitably come at the expense of the other? These important questions are considered in this December 2012 OpEd for Al Jazeera English: Instagram Arms Control

Image Credit: Mashable

#instagram#arms control#facebook#twitter#state department#wmd#internet freedom#al jazeera#foreign affairs

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WWF Drones and Internal State Security

We are currently bearing witness to great changes in international security. Gone are the days of state monopoly over internal and external security agencies. State policing and military agencies are now serving alongside a variety of global, regional, and subnational security providers.The latest to join this mix of non-state actors is the World Wildlife Federation (WWF), who just announced a new Google-backed anti-poaching campaign complete with drone surveillance. But, is this really a good idea?

Al Jazeera English: WWF Drones Raise Serious Questions for International Security

Image Credit: Conservation Drones

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Arab Spring' Unlikely in Cambodia?

This month, Faine Greenwood published her latest article, "Sitting Pretty," in the Southeast Asia Globe. The article addresses the current political situation in Cambodia and asks whether the incumbent regime has anything to fear. Its subline accurately captures its tone and substance by concluding, "observers say the leadership has little to fear." I am one of those observers.

Since Greenwood was only able to use a small subset of comments made in our far-reaching interview, I wanted to provide the full interview responses below. I would love to hear if you agree or disagree with my perspective and those of other scholars, including Dr. Carl Thayer (UNSW@ADFA) and Joel Brinkley ("Cambodia's Curse").

“My take on the whole situation in Cambodia is that, absent a new economic crisis in Southeast Asia, you won't see an 'Arab Spring' situation anytime soon."

"That said, the legitimacy of the incumbent regime is based upon its ability to provide Cambodians increased wealth and prosperity. This means that the regime needs economic growth to insulate it from criticism and prop up its patronage-like system.”

“With the Indian economy slowing and Chinese economy showing cracks, there has to be some concern that the regime couldn't maintain legitimacy should a new economic crisis take hold in Southeast Asia.”

"If you look back at what toppled Suharto, it wasn't the fact that he was opposed to the democratic process taking hold in Indonesia. It was the economic crisis, and the fact that after years of providing increased prosperity to Indonesians, it finally gave way. If that sort of situation was repeated in a regional context, I think the incumbent regime (especially the Prime Minister) would face increased opposition. Whether that would lead to the regime's collapse depends on the scale of the crisis."

"It’s not just bilateral trade with China that you have to worry about. It’s the web of interdependency. At the end of the day, if a new economic crisis emerges, it's not just a bilateral economic relationship between Cambodia and China that the regime needs to worry about. If China's economy slows considerably, other economies upon which Cambodia depends will suffer."

"Cambodia will be hit on multiple fronts if China's economy really slows, and there's little the regime can do in the short-run to offset the negative impact. That's the scenario which should concern the regime the most."

"To some extent, ASEAN insulates countries from regime change because of the members' commitment to non-interference. The region as a whole embraces this idea of non-interference, which sometimes doesn't live up to expectations. But in reality, it's a huge obstacle, because they've committed to not interfering with each other. If another ASEAN member would cross the line in Cambodia, it would challenge the very principles which underpin ASEAN."

"I don't see external powers provoking a Cambodian Arab Spring. No one wants to interfere in Cambodia and risk promoting instability in the region."

Photo Credit: quartje (Flickr)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Protecting Endangered Languages: Smart Public Diplomacy?

Eddie Walsh is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Australian and New Zealand Studies in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. He also serves as the Vice Chair of Foreign Correspondents at the National Press Club and a WSD-Handa Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS. Follow him @aseanreporting.

Image Credit: Hawaii Air National Guard (Flickr)

#pacific islands forum#state department#clinton#diplomacy#public diplomacy#smart power#soft power#foreign policy#pacific islands#fiji#hawaii#hawaiian#chamorro#guam#american samoa

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obama’s Empty Pivot in the Asia-Pacific

Although coined by Joseph Nye, the practice of soft power diplomacy is of course nothing new. It has always played some role in American foreign policy — even in the days of gunboat diplomacy. However, it has never before served as the central tenet of American foreign policy strategy because previous administrations always recognized that soft power diplomacy does not work in the absence of hard-power leverage. That is why we have continuously invested in the world’s most dominant military.

As Americans, we must be realistic about our future. There is no guarantee that the balance of power in Asia will remain in America’s favor. Sending a few thousand Marines to Australia or convening meetings with regional partners might serve as nice data points at news conferences. But, they are not enough to ensure that the United States remains dominant in the Western Pacific. We need to do something far more substantive than what the Obama administrationhas done to date.

The problem with the administration’s current approach is the unwillingness to make hard decisions when it comes to reorienting the U.S. military’s force structure in the Pacific. Obama officials are not willing to commit to developing new platforms and weapons systems required to counter emerging threats emanating from Asia. Instead, they promote public diplomacy and strategic communications that do little more than send mixed signals to potential strategic competitors.

The South China Sea is a great example. When the United States closed its bases in the Philippines, America lost its hard-power leverage in the region. A power vacuum was created when the Association of Southeast Asian Nations could not match the strategic influence of the U.S. forward presence. This, in effect, provided China with an opportunity to challenge the regional order and redraw the borders in its favor. What did China do? It pounced at this opportunity — exactly as realists would expect.

The point here is that the United States cannot rely on soft-power diplomacy alone to promote our interests in Asia. We need to establish a strong forward presence in the region that sends the right signal to potential regional competitors that the U.S. is not going to allow others to challenge peace and stability in the region through coercive actions. This is not about containing others but it is about maintaining primacy. We should not shy away from saying that is our objective.

In the end, the United States cannot continue to be caught empty-handed in Asia. We need the Obama administration to be far more decisive in implementing the change required to ensure our primacy in the region. Politics aside, we cannot afford to see our Asia pivot devolve into another Russian reset fiasco — the stakes are just too high. That’s why we need the Obama administration to reconsider its approach in Asia even though it’s an election year, when domestic issues predominate.

Image Credit: U.S. Navy Official (Flickr)

#soft power#public diplomacy#communications#foreign policy#china#asia#joseph nye#obama administration#hard power#marines#australia#defense#asia-pacific#south china sea#asean#philippines

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Respond to Chinese Revisionism?

The Obama Administration was right to diplomatically confront Russia, however weak, for its support of an illegitimate regime willing to bomb its own people. The problem is that China, who also used its veto, has not been held to task for its unwillingness to denounce the Syrian regime. Why then the double standard?

In large part, the fault lies directly with the Obama Administration. They have demonized Russia in press conferences but held their tongue on China. One can only surmise that this reflects their strategic decision to passively accommodate rather than actively confront a rising China.

The South China Sea is a great example of the U.S.' timidity. When the U.S. closed its bases in the Philippines, America lost its hard power leverage in the region. A power vacuum was created and ASEAN could not match the strategic influence of the U.S. forward presence. China then responded by challengingthe status quo and threatening its Southeast Asian neighbors with use of force by its growing navy.

The Obama Administration was caught flat-footed but nevertheless tried to pivot. Their late response was to wage a high-level diplomatic campaign against Chinese aggression in the region. They also announced a new basing agreement in Darwin, Australia for a small contingent of U.S. Marines.

The problem is that these small efforts fail to address the strategic root of the problem -- the U.S. lacks the sufficient forward presence in the Western Pacific to disincentive China from threatening use of force against its neighbors. And U.S. allies are concerned.

To be fair the new basing agreement in Darwin is a step in the right direction. But, a few thousand Marines are more of a symbolic nuisance than a strategic deterrent for the Chinese. This undermines the very rhetoric voiced by the Pentagon and State Department.

The Obama Administration must also rethink its overall defense strategy. Over the last four years, they have promoted the development of an agile, Special Forces-oriented military backed with top-secret strategic assets based far from the battlefield.

Such assets might be appropriate for killing terrorists or waging a nuclear war but they do little in the way of addressing Chinese aggression in Asia. Why? Because no one really believes that the U.S. is going to risk nuclear war over a conflict in the South China Sea unless American (or possibly its allies') forces are attacked.

If the U.S. wants to counter Chinese aggression in Asia, the Obama Administration needs to be more consistent in their approach against strategic adversaries and back-up its diplomatic rhetoric against China with hard power leverage. And, the first step should be to increase the American military's forward presence in Asia.

Image Credit: Philippine Fly Boy (Flickr)

#south china sea#obama#huffington post#richard grenell#china#asia#philippines#marines#australia#pacom#state department#pacific#strategy#pentagon#syria#russia

1 note

·

View note

Text

U.S. Must Send Right Signals to the Pacific

Last year, the United States sent its largest and highest-level delegation ever to the PIF. This strong showing was seen by many as an indicator of a larger and more substantive shift in U.S. regional engagement. Unfortunately, this shift (like the larger Asian pivot) has yet to materialize - leading some regional diplomats to question the U.S. approach.

The U.S. can ill-afford to repeat these mistakes. The Pacific Islands countries sit at the geopolitical crossroads of the Asia-Pacific century. China and other Asian powers will capitalize on further American missteps; eroding the power and influence of the U.S. and its allies in the process.

If the U.S. intends to lead in the Pacific, there is no question that Secretary Clinton should head the U.S. delegation. However, she cannot do so empty-handed. The U.S. Government must recognize that the size of its diplomatic contingents provide little more than talking points at Beltway think tanks. What the region is really looking for the U.S. to back its diplomatic posturing with serious on-the-ground investments.

The problem for the State Department is how to muster the political and financial resources necessary to make such investments in an election year marred by escalating conflict in the Middle East and global economic uncertainty. U.S diplomats must also overcome an entrenched American mindset that takes for granted Western power and influence in the Pacific - a remnant of the Cold War where the region was seen as a strategic backwater. Neither will be easy.

If the State Department cannot overcome these challenges and match regional expectations, the U.S. should not send Secretary Clinton to Rarotonga and Aitutaki.

Instead, the U.S. should send a lower ranking diplomat, such as Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell. His presence would much more accurately reflect the present U.S. commitment to the region; sending the right signal to regional partners.

Image Credit: U.S. Department of State (Official)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small State Dynamic in Fiji-Australia Relations

The vast majority of the world's small states are the developing small island stateswhich dot the Pacific and are far removed from major regional centers. Profoundly dependent on tourism and primary export crops, these states are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in the global economy. As a result, many are heavily dependent ondevelopment aid and emergency assistance. In return, Australia and its allies have carved out a sphere of influence in the Pacific which has gone unchallenged for decades.

Despite these challenges, however, Australia remains the dominant strategic player in the Pacific where it matters most: development aid, trade and investment, and regional security. But defending this leadership position comes at no small cost to Australian taxpayers. In 2011-12 alone, the government expects to provide $1.16 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Pacific island countries and Papua New Guinea. To put this in perspective, that figure represents almost half of all global ODA for the region and a quarter of Australia's total budgeted ODA .

This allocation, of course, leads to periodic debates over whether the expenditures are worth it, especially when Australia's small island neighbors present no immediate threat to anyone. Despite these debates, Australian fears of an "arc of instability" in the Pacific - coupled with uncertainty over the strategic expansion of China and other Asian powers into the area - have thus far insulated its ODA policy from attack. That Australia's bid to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council, relies in part on a robust foreign presence has not hurt the policy either.

Given all the above considerations, the question moving forward is whether Australia can sustain its leadership in a region now undergoing large-scale changes. An examination of the state of Australia-Fiji relations illustrates this point particularly well.

Fiji's Power Play

Despite being the obvious junior partner in its relationship with Australia, Fiji's current regime managed to exploit Australian strategic insecurities when it took power after a 2006 coup. Soon after the takeover, Commodore Frank Bainimarama and his allies concluded that as long as they maintained internal order in Fiji, Australia would not militarily intervene. Such a reaction, they reasoned, would set a bad precedent in a region where small states remain wary of being pushed around by a dominant power.

In effect, this line of reasoning held. Australia could not afford to have its regional dominance perceived as a threat. A military intervention would have compromised its 'soft power' credentials and encouraged its small neighbors to explore new collective or bilateral security arrangements. In the end then, Canberra was forced to settle forless punitive measures against Fiji. It could do little to prevent the Bainimarama regime from tightening its grip on power, or from adopting policies not in Canberra's interests.

Australia's decision not to intervene in Fiji's internal affairs also allowed the latter to 1) pursue bilateral policies aimed at reducing its lopsided dependence on its larger neighbor, and 2) undermine international support for Australia's hostile attitude towards the new government. This has included playing the 'China card'; indeed, as one Western diplomat recently put it, "Fiji has very publicly 'looked north' in the wake of its suspension from the Pacific Islands Forum." This look north has also sought to strengthen Fiji's relations with other Asian powers, particularly Japan and specificASEAN member states. It even tried to transform the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) into a viable alternative to the Pacific Islands Forum, and a possible coalition for resisting Australian influence .

On the domestic front, Fiji's new government used its confrontation with Australia to minimize Canberra's strategic influence in key commercial sectors, including media and tourism. In 2010, for example, the government forced the sale of the Fiji Times by requiring the Australian-based News Corporation Limited to divest all but 10% of its interest in it. More recently, a row erupted with Qantas Airways when it was informed that two-thirds of Air Pacific's directors, in which Qantas holds a 46% stake, would now have to be Fijian citizens. (Many have characterized this move as a veiled effort by the Fijian government to take over the airline, in which it is the majority stakeholder.) Both moves have spurred mixed emotions, with Fiji asserting itsright to protect itself against unduepolitical and commercial interests, and Australia countering that the moves illustrate Fiji's new authoritarian tendencies.

The lessons from the above tale are fairly clear. Small state-large state dynamics at play in recent Fijian- Australian relations demonstrate that Canberra's power and influence in the Pacific can be checked by smaller neighbors exercising deft diplomacy. Right or wrong, Fiji has successfully exploited Australia's strategic anxiety about intervening in the internal affairs of its smaller neighbors. On more than one occasion, therefore, this has allowed Fiji to increase its diplomatic leverage against Australia.

But, experts caution, Fiji must not overplay its hand. While for the time being it may have carved out the space needed to implement policies that run counter to Australian wishes, the government has also committed itself to reinstating democracy andnormalizing its foreign relations. If the Bainimarama regime fails to deliver on these promises, it may prove unable to maintain internal stability and public order, with powerful internal and external actors then being willing and able to foment unrest. Under such circumstances, Australia would find it far easier to intervene, under the aegis of either a regional (Pacific Islands Forum) or international (Responsibility to Protect) mandate. If this were the case, Fiji's daring and controversial record of standing up to Australian power in the Pacific would come back to haunt it.

Image Credit: U.S. Navy

Creative Commons - Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Papua Needs Inclusive Policy Approach

Separatism in Papua is a complex issue with many underlying, interrelated causes. Geolocation, history, and identity (ethnicity/religion) all play an important role in the parties’ construction of the conflict. These are reinforced by another set of factors: political, economic, social and humanitarian grievances. The question is: which set of factors is more amenable to resolution and thereby affords a better opportunity to stabilize the conflict? Full article available at Strategic Review: The Indonesian Journal Leadership, Policy, and World Affairs

Image Credit: David Jackmanson

0 notes

Text

Australia Uranium Deal: A Risky Proposition

While the tabloid media has savored the opportunity to skewer Rudd, his failed attempt to lead the government has consequences beyond his own political ambitions. On the foreign policy front, the Gillard Coalition will likely now reorient the country's foreign policy toward the Asia-Pacific region.

This shift away from Rudd's global foreign policy approach should prove popular with many Australian voters; possibly increasing support for Gillard which is already on the rise.

That said, a number of important foreign policy issues will continue to divide Labor as Gillard looks to consolidate her power. One of the most serious is her position on Australian uranium exports to India. This poses a chronic risk for both Gillard and the Labor Right - just as it does for the United States.

Post-Rudd Shift

Under Rudd's tutelage, Australia assumed an expansive foreign policy approach. This included launching a major campaign to secure a seat on the U.N. Security Council and enhanced security and aid roles faraway from home, including Libya, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Caribbean.

Not all of these efforts have been welcomed by Australians. Many question whether Australia wouldn't be better served focusing on its core interests in Asia-Pacific, including bilateral relations with Indonesia. Some also fear that Rudd's global approach threatens to entangle Australia in the security interests of others; thereby risking global escalation of regional or national conflicts.

Rudd's replacement, Bob Carr, appears ready to right some of these perceived wrongs and slowly shift Australian foreign policy toward regional interests at the expense of those farther afield. Although it is possible that this could destroy Australia's U.N. Security Council seat bid, many feel that this better reflects the capabilities and interests of a middle power like Australia.

While Gillard's strong showing provides the political mandate for a foreign policy reorientation toward Asia-Pacific, the leadership vote certainly was not a black and white referendum on Australian foreign policy. Domestic policy positions were key to the vote, as were questions about character, governance, and leadership. Ultimately, it was about who would be best poised to sustain Labor's grip on power.

Given that Australian uranium exports to India fail to resonate with voters, it is perhaps not surprising that this issue did not propel Rudd to victory. Despite the fact that Rudd and Gillard maintain radically different perspectives, Labor members of Parliament appear to have overlooked the issue in favor of those which will determine the immediate political fate of the party.

India Debate

Still, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) remains deeply polarized following last year's Federal ALP Conference vote to allow uranium to be exported to India. Gillard's victory did little to end this bitter divide.

Although the export issue has not garnered significant media attention of late, the Labor Left and others remain fiercely opposed to uranium exports to India. They reject Gillard's argument that the economic stimulus generated through job creation in the mining sector justifies the perceived risks to global peace and stability.

The 55% of the ALP that leans to the right, on the other hand, supports Gillard's approach. They agree that the greater risk would be to deny India its rightful place in the international system.

Such political dissonance renders Gillard's pro-export policy approach susceptible to future challenges. But who could lead such an anti-export campaign?

Political Consequences

While Rudd has been vocal in opposing uranium exports to India in the past, it would be incredibly difficult for the former prime minister to lead the charge against Gillard. Having failed to fully mobilize the opposition in the leadership vote, he probably lacks the political capital necessary to spearhead such a major challenge anytime soon.

The question then is whether the Labor Left's leadership will be willing to rally its supporters, possibly in alliance with other Labor and non-Labor factions, and wage such a campaign. Only time will tell but such a political quarrel remains a distinct possibility.

The problem for Gillard is that the Labor Left can afford to be patient and wait for an opportune moment to strike. They know that they need stronger political ammunition to defeat Gillard and the Labor Right. And, they know that the passage of time could provide it.

Patience as a Virtue

There remains lengthy process and verification hurdles before uranium exports to India can fully come into force. During this period, the Labor Left can take advantage of any information which bring into question Gillard's underlying assumptions for moving ahead with supplying uranium to India's nuclear industry.

What sorts of events could trigger the opposition to take action? Any indication that Indian plans to redirect Western uranium imports to its military programs, conduct another nuclear test, or develop relations with state or non-state nuclear proliferators would suffice. A major nuclear incident, such as an accident at an Indian civilian nuclear facility blamed on poor nuclear safety compliance, could also bring Gillard's policy approach into question.

Although these examples fall outside of the Australian Government's direct control, they nevertheless could be used to challenge Gillard's leadership on the matter. Opponents can say that she individually and the Labor Right collectively have made Australia "complicit in nuclear proliferation" or "negligent on nuclear safety." Such accusations could mobilize the electorate and finally make the issue politically salient.

No matter how improbable such scenarios appear to her supporters, Gillard cannot afford to be proven wrong on uranium exports to India. Despite their present indifference to the issue, Australian voters would probably not accept a political mea culpa should serious concerns with India's civilian and military nuclear programs emerge.

What's at Stake

Under the right conditions, Australian uranium exports to India thus provide a viable mechanism by which Labor's opposition can restore their standing in the party.

There is no hiding the fact that the cards would certainly have to fall their way. But, Gillard's supporters must acknowledge that the Indian Government could gift Rudd, the Labor Left, and/or others the opportunity to challenge her leadership if the Indians fail to adhere to their part of the bargain.

While Gillard's faction has won the day, her side must accept the risk that history could prove her position flawed. If so, the Gillard Coalition (or its successors) might have to recognize the opposing Rudd and Labor Left position as proper.

Unlike Carr's recent concession that Rudd was right on Libya, the Gillard Coalition may not have the option of backtracking on this one. If their err in judgement places Australia on the wrong side of nuclear proliferation or nuclear safety history, Gillard and the Labor Right would face political kryptonite capable of removing them from power and tarnishing their records forever.

Avoiding Icebergs

In all honesty, I seriously doubt that Gillard worries about such an unkind future. Like U.S. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, her support for uranium exports to India appears driven by a deep conviction that she is right. This sort of confidence is of course what one would expect from a world leader taking a stand on a difficult issue. One only hopes Gillard's faith in Indian intentions is not misplaced.

If her assumptions prove unfounded, the domestic political consequences for Gillard and the Labor Right will be severe. But, even more importantly, U.S.-Australian relations could be seriously strained during a crucial transition period for international security. This is because some Australians would probably condemn American "meddling" in their foreign policy decision-making given the direct role the Obama Administration allegedly played in Gillard's policy shift on uranium exports to India.

To mitigate these concerns, Australia, the United States, and their allies must remain ever vigilant in ensuring that India abides by its commitments. Any indication to the contrary should be met with coordinated diplomatic vigor typically reserved for countering one's adversaries not one's partners.

Image Credit: Jess and Peter Gardner (Flickr)

0 notes

Text

Why Congress Cares About Iran-Venezuela

Image Credit: Daniella Zalcman

0 notes

Text

Will Fiji Overplay Its China Card?

Positions of Regional Powers

Since the 2006 coup, Australia has taken the most uncompromising positions on Bainimarama. Working vigorously to isolate the regime and enforce sanctions until there are "credible signs" of a return to free elections, Australia has imposed strong sanctions, including suspension of ministerial contact and defense cooperation, an arms embargo, and visa restrictions.

China was once at the other extreme. In the immediate wake of the coup, paranoid that Fiji would move to recognize diplomatic rival Taiwan, China stepped in with promises of over $150 million in aid. However, with time and a diplomatic truce with Taiwan, China realized this fear was overblown and that its reaction was putting strain on its much more important relationship with Australia as well as the United States. China then delayed the rollout of its aid pledges and cut back on cash donations -- suggesting that Fiji's China card is itself overblown. That said, China remains the strongest supporter of the regime among the regional powers.

For the United States's part, while it has hewn closer its ANZUS partners than China, U.S. diplomats have tried to forge something of a middle ground by adopting a less uncompromising approach to sanctions and generally look for areas -- like crisis response and human trafficking -- through which to engage Fiji. This has been welcomed by the current regime, that has argued the United States could play a leading role infacilitating the country's return to a democratic government as a result.

Possible Outcomes

So, what are the strategic implications for these positions on the respective powers? To a large extent, this depends on whether Bainimarama is who he says he is or not. The decisions the regime makes in the next three years will provide the answer. Reflecting the uncertainty surrounding Fiji's future course, at present, four scenarios appear most likely.

Stable Western Style Democracy: A stable democracy could take hold if Commodore Bainimarama succeeds in the reforms that he claims to champion. This would require implementing strong social and economic policies which would mitigate the deep racial cleavages which have divided Fiji for decades. It also would require a concerted effort to reconcile political interest groups who were positively and negatively impacted by the coup. Finally, it would require the drafting of a constitution that would garner cross-spectrum support and the holding of free and fair elections that would bring an end to the coup. This latter goal received a positive, if small, boost last week with the announcement of a 'comprehensive consultation process on the new constitution'.

Stable Guided Democracy: Given Fiji's serious political, economic, and social divisions, Bainimarama's rejection of Western-style democracy should not be ruled out. Instead, his regime could oversee a form of guided democracy. In this scenario, the regime would maintain de facto control over Fiji's politics and the media through the use of coercive military-backed tactics to ensure elected politicians and the media remain compliant with military interests. Unlike autocracy, guided democracy would be notionally legitimized through elections, but if the unofficial compact unraveled, would result in another military coup to restore the status quo.

Unstable Democracy: An unstable democracy could take hold if Commodore Bainimarama follows through on his commitment to restore democracy but fails in the reforms that he claims to champion. Under this scenario, the regime fails to effectively implement the social and economic policies that might mitigate the deep racial cleavages which have divided Fiji. There also likely would be no reconciliation of political interest groups. In the end, the elections would be held but the country would soon face yet another coup.

Autocracy: An autocracy could take hold if Commodore Bainimarama is not sincere in the reforms that he claims to champion and/or realizes he will be unable to implement his reform agenda. In this scenario, Bainimarama would use the run-up to elections to consolidate his political power and silence his opposition. When completed, he would abandon the premise of free and fair elections and remove any existing legal or legislative checks on his regime's powers.

Strategic Implications

While politicians may claim to know what path Bainimarama will choose, the history of the 2006 coup has yet to be fully written. For this reason, it is valuable to shift the discussion, at least for the moment, away from "What will Bainimarama choose?" to "What impact will each of the probable outcomes have on the strategic interests of the regional players?"

Stable Western Style Democracy: If Fiji holds reasonably free elections in 2014 under a constitution that removes racial biases and ensures political competition, all sides will likely claim vindication for their respective Fiji policies. In the short-term, tensions might remain raw between Fiji and Australia as Bainimarama (likely still in power) could argue that he was slandered while Australia could claim their sanctions succeeded in pressuring the Commodore into adhering to democratic reform. However, in their national interests, the long-simmering controversy would likely die down quickly as the two democracies push to normalize relations. In the meantime, as non-parties to this intra-Oceanic bickering, the United States and China would find themselves with clean hands from which to more aggressively pursue their national interests in the South Pacific.

Stable Guided Democracy: If Fiji pursues Turkish-style guided democracy, Australia might find itself wedged and its position weakened in the South Pacific. The government in Canberra has been so uncompromising and taken such strong public positions that it would be very hard for it to accept managed democracy in lieu of liberal democracy. Conversely, the United States and China would be better positioned to accept a stable managed democracy and to capitalize on such moves by the regime.

Unstable Democracy: According to James Clad, a former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, an unstable democracy marred by race-based politics and possible conflict would present "the most headaches for Australian foreign policy." In essence, this is the nightmare scenario for Australia because they have secured the free and fair elections that they have demanded since 2006 but the entire premise of Bainimarama's anti-democratic efforts are validated. In this scenario, the United States and China would be in a far better position to advance their strategic interests in the region in the aftermath of the crisis.

Autocracy: If Bainimarama instead treads down the well worn path of entrenching his dictatorship, deeper fractures may begin to emerge. Australia probably will feel vindicated in its harsher position. Arguing that Bainimarama is a megalomaniac whose ambitions are antithetical to democracy, their calls for regime change could strengthen. This likely would force the United States to abandon its current policy preferences and fall in line with its ANZUS partners. As a consequence, Fiji probably would attempt to reach out to China, a move that would likely be futile however, because of Chinese concerns about undermining more important economic relations with Australia.

So which country's position is going to be vindicated? That depends who you ask. And, truth be told, no one knows for certain except Bainimarama.

Co-authored with Fergus Hanson.

#fiji#china#australia#united states#geopolitics#grand startegy#diplomacy#security#autocracy#democracy#startegic

0 notes

Text

Congress Playing with Balochistan Fire?

This alternative policy centres on backing remnants of the Northern Alliance and Baloch insurgents, who seek to carve out semi-autonomous territories or independent states from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran.

While supporters of this new approach are motivated by a variety of interests, they appear unified in their rejection of what they see as three cornerstones of the Obama administration's current regional policy approach: 1) Normalising relations with Pakistan's government and military; 2) Incorporating the Taliban into the current Afghan political system; 3) Overly accommodating an emerging Iran.

In one broad stroke, this new approach would attempt to advance US national interests by redrawing the political borders of Southwest Asia - contrary to the the sovereignty and territorial integrity of three existing states.

While its advocates clearly do not yet have broad support for their initiative, the campaign for an alternative Southwest Asian policy approach is maturing and garnering increased attention in Congress and beyond, especially as a result of three recent high-profile events: a Balochistan National Front strategy session in Berlin, a US congressional hearing on Balochistan, and the introduction of a Baloch self-determination bill before the US Congress.

Regardless of whether you agree or disagree, it's nevertheless critical to understand how this alternative policy approach framework has evolved over the past few months.

The 'Berlin Mandate' as a loose framework

In early January, a bipartisan congressional delegation, led by Representative Dana Rohrabacher (Republican-California), held a "strategy session" in Berlin with Afghan opposition leaders, including the country's former intelligence chief. The meeting addressed constitutional reforms that would make Afghanistan a federal system.

Meeting participants argued that vesting political and economic power in the provinces, instead of centralising power in Kabul, would protect the US' Northern Alliance allies from retribution at the hands of Pashtuns once the Taliban is fully reincorporated into the Afghan political system.

By advancing these policies, the attendees portrayed the Taliban's incorporation into Afghanistan's political system as a greater risk than the threat posed to Afghanistan's territorial integrity by their alternative - which would risk the partition of "Afghanistan between the minority-dominated north and the Pashtun south". This clearly runs counter to the the interests of Hamid Karzai's government.

A few weeks later, Representative Louie Gohmert (Republican-Texas), a Berlin meeting attendee, added fuel to the fire by arguing in a videointerview that the US should not just push for a new political system in Afghanistan but go further by rearming the Northern Alliance.

In the same breath, Gohmert provided one of the first definitive links between support for the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan and Baloch nationalists in Pakistan: "Let's talk about creating a Balochistan in the southern part of Pakistan. They'll stop the IEDs and all of the weaponry coming into Afghanistan, and we got a shot to win over there."

With these remarks, the two pillars of an alternative Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) policy approach were now set: To advance its interests, the US should support the carving out of an independent Baloch state and semi-autonomous Afghan territories - even if it undermined existing US partnerships with the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In early February, Rohrabacher convened a public congressional hearing on Balochistan. While human rights violations in Pakistan's Balochistan province were discussed (per the agenda), the hearing also provided a forum to start a larger (and arguably off-topic) national dialogue on the viability of Southwest Asia's state borders.

As a result of the hearing, witnesses - including Ralph Peters and M Hossein Bor - were able to argue that the dismemberment of Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan would serve the United States' long-term strategic interests. But, even more importantly, the hearing allowed the witnesses to inject their views into the larger debate on US foreign policy in Southwest Asia. This included Bor's controversial assertion (which was later censored in Pakistan) that supporting an independent Balochistan stretching from "the Strait of Hormuz to Karachi" would be a better policy approach than ongoing US efforts to counter the Iranian and Pakistani regimes.

Rohrabacher, Gohmert, and Representative Steve King (Republican-Iowa) followed up the hearing by introducing a new bill in Congress stating that the Baloch nation has a historic right to self-determination. With this action, the congressmen went from "familiarising themselves" with Balochistan to calling for Congress to recognise the Baloch nation's right to sovereign independence in roughly a week.

In many ways, this brought the "Berlin Mandate" full circle. In less than two months, a small group of congressmen, minority Afghan groups, Baloch nationalists, and their supporters had gone from voicing displeasure with the current Obama Administration's Af-Pak policy approach to advancing a revolutionary alternative policy approach that called for supporting the minority interests of the Northern Alliance and Baloch against the sovereign interests of Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan.

Reflecting upon this effort a few days after the bill was introduced, Rohrabacher confided to me in an on-the-record interview:

"There is a natural extension from the Berlin meeting with the Northern Alliance to the Balochistan bill. I have always stood for self-determination, but there are certain things that activate me to start pushing more on that philosophy. Clearly, the whole issue of the Taliban being reintegrated in Afghanistan and Pakistan, providing safe haven to terrorists like Bin Laden, are major factors.There is also my support for immediately withdrawing troops from Afghanistan. To do so, we need to have a major policy dialogue on what our policy is in Southwest Asia, how we properly transition out of Afghanistan, and what will be our ongoing relationship with Pakistan. Balochistan is clearly part of that debate."

Cross-linking with other congressional causes

While the introduction of the Baloch self-determination bill marks an important milestone for their cause, it is important to point out that there has been an equally big change in how "Berlin Mandate" supporters have advocated their cause. Over the last month, these supporters - particularly Baloch nationalists in the US diaspora - have increasingly sought to extend their cause beyond US foreign policy in the Af-Pak region. They appear to recognise the need to latch onto larger foreign policy issues as part of their efforts to garner mainstream support for their cause. Four of the most important include:

I. Punishing Pakistan for supporting terrorism and nuclear proliferation

Rohrabacher, Gohmert, and other key supporters of the alternative policy approach for Southwest Asia have been unabashed in overtly linking the need for policy alternatives to Pakistan's "betrayal of America's trust". It is evenalleged that the Balochistan hearing was called specifically to "stick it to the Pakistanis" for their arrest of a reported key informant in the bin Laden operation. Even after widespread criticism for his past remarks against Pakistan, Rohrabacher does not shy away from his criticism: "Quite frankly, the Pakistani military and leaders that give safe haven to the mass murderer of Americans should not expect to be treated with respect."

Such rhetoric almost certainly will find a receptive audience in Congress - even among the many members who have never heard of Balochistan or know little about the Northern Alliance's struggles over the last year. For this reason, Peters pointed out to me recently as part of a yet unpublished post-hearing interview that the current high levels of anti-Pakistani sentiment in Congress probably provide the best opportunity that the Baloch may see to advance their cause.

II. Containing a rising China and an emerging Iran, and preventing Pakistan from achieving strategic depth

According to supporters, an independent Balochistan, "extending from Karachi to the Strait of Hormuz", would help to contain a rising China and an emerging Iran, provide a long-term security guarantee against China, Iran, and Pakistan emerging as maritime powers, and undermine the strengthening of strategic relationships between these three potential adversaries.

In an interview after the congressional hearing, Bor made this case:

"There are many interrelated issues at play. When one discusses Balochistan, you are discussing a way to contain China. You are also discussing economic relationships between Iran and Pakistan … If (the Chinese) build their port in Gwadar, they will have a land route from Western China to the Indian Ocean.

This is of strategic interest to the United States because Chinese ships would have a direct route to China and no longer have to transit past the Indian and American navies. It therefore is logical that Balochistan should be concerned as part of the larger shift to the Pacific announced by the Obama Administration. … (Separately,) Iran is an empire and they are using Baloch lands to try to become the dominant regional player. The Iranians are using the Strait of Hormuz as a choke-point for a huge percentage of the world's oil. They also are building a pipeline to Pakistan which violates UN sanctions. Such growing Iran-Pakistan cooperation is a major concern."

Other supporters have advanced similar arguments with respect to Afghan minority groups against the Pashtun-dominated central government. They assert that support for the autonomy or independence of the Northern Alliance serves as an insurance policy against Pakistan's military achieving strategic depth once the Taliban is fully integrated into Afghanistan's political system.

III. Providing the West with an opportunity to profit off of Southwest Asia's natural resources

Recognising "the tremendous deposits of oil, gas, and minerals" found within or made accessible through the Baloch and Northern Alliance territories, some supporters have argued that the West should advance the "Berlin Mandate" if for no other reason than self-serving economic interests.

They have asserted that an independent Balochistan and autonomous Northern Alliance territories would provide Western companies with valuable new economic opportunities, which could help offset the costs of two failed wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and spur economic growth following the global economic downturn. They have also said that the West should do so to prevent potential strategic adversaries, including China, Iran, Pakistan, and Russia, from profiting off the natural resources of Central and Southwest Asia at their expense.

While Rohrabacher has called this "a bunch of leftist garbage from liberal professors", it must be said that his committee purposely selected a witness whose expertise lies in forging such partnerships in the Middle East region and who remains a vocal advocate for their consideration in the context of an independent Balochistan. Baloch nationalists clearly have started to reach out more aggressively to Western commercial interests on these grounds in recent months as well.

IV. Preventing gross human rights violations and providing post-colonial nations their right to self-determination

While members of Congress have long condemned the Taliban and the Pakistani government for human rights violations, supporters - particularly Baloch nationalists - have used novel approaches in recent months to win over members of Congress. They have increasingly restrained themselves from leading with the genocide argument. Recognising that this argument has failed to win over Congress in the past, they have instead turned to a more complex argument: that the Baloch, like the South Sudanese and numerous minority groups in the former Yugoslavia, have won their right to self-determination because Pakistan and Iran have failed to provide basic human rights protections. Pakistan and Iran have, they argue, thereby forgone their sovereignty over Baloch territories - regardless of historical precedent.

While few in Congress will support their cause on these grounds alone, Baloch nationalists acknowledge the moral power of the argument for members of Congress who may be seeking to justify their support for an oppressed group on other grounds. This argument could become a powerful advocacy tool for Baloch and Afghan minority interest supporters, especially when reaching out to congressmen serving on other minority group interest caucuses with their own claims to self-determination.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Uncertain Future for Fiji?

In the Doghouse

In December 2006, Suva further entrenched its reputation as the coup capital of the South Pacific when Bainimarama removed Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase's duly elected but troubled democratic government. This marked the fourth coup since Fiji's independence from Britain in 1970.

Since the coup, Bainimarama - acting as self-appointed Prime Minister - has talked the talk of a progressive savior. He has announced grand plans to rid Fiji of its deeply entrenched racial divisions between ethnic Fijians and Indo Fijians. He also has promised better and fairer education and economic opportunities that supposedly only a strongman can deliver.

Such policies prey on the very real insecurities of a country that has witnessed the destabilizing effects of race-based politics for a significant part of its post-colonial history. Coupled with Bainimarama's tight grip on the military and media, the coup therefore has been met with a relatively muted response within Fiji.

Western countries and the Fiji diaspora, on the other hand, have been more forceful in their opposition. Australia and New Zealand in particular have leveraged their bilateral and regional influence to try and coerce Bainimarama's interim government to hold free and fair elections. Their position: Commodore Bainimarama is a dictator whose ambitions are antithetical to democracy.

The question then is whose coup narrative is right. Do the Commodore's tactics provide the stability required to implement corrective policies and finally unite a deeply cleaved society? Or, is Bainimarama no different than other post-colonial despots who have risen to power on baseless promises only to deliver pain and suffering to their countrymen and women?

Competing Narratives

Since overthrowing Qarase, the Commodore has remained consistent in his position that Fiji lacks the conditions necessary for democracy to function. His supporters also argue - that the regime has kept to the high-level milestones for reinstating democracy originally outlined in his 2009 strategic framework. They even claim that the regime has already instituted policies aimed at redressing the racial divide through economic and social development and lifting the draconian Public Emergency Regulations which oppressed free society in the aftermath of the coup.

However, in the eyes of the West, Bainimarama's claim that he is taking concrete action to restore democracy is viewed as baseless. They point to the fact the regime has instituted harsh censorship laws, sacked the judiciary, and cracked down on unions, media, church leaders and civic activists. It has failed to be transparent and provide economic and social data that would support its argument that domestic policies are bridging the racial divide. Furthermore, it has severely undermined the positive response generated from the lifting of the PERs by implementing a new Public Order Act, which quickly resurrected most of the concerns that the lifting of the PER sought to redress.

Uncertain Outlook

So, how will history remember Bainimarama? Much depends upon whether the Commodore is sincere in his commitment to drafting the new constitution by the end of the year and holding elections by September 2014. If Bainimarama dramatically picks up his game and delivers on the commitments outlined in the strategic framework, he might yet salvage his reputation and restore democracy. However, if he deviates from his self-prescribed milestones and the 2014 elections prove to be "a pipe dream," then Australia and New Zealand will find their position validated. Dictators do not have a great track record in following up on their commitments. So, it is now all up to Bainimarama and the people of Fiji to decide how history remembers the regime.

Co-written with Fergus Hanson (Director of Polling and Research Fellow at the Lowy Institute in Australia)

Image Credit: Jennifer (Nopsa)

1 note

·

View note