Notes on translation, Remedios Varo & more. Margaret Carson tweets at @margagram

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Pauline Peavy, mystic, channeler, artist, at the Armory Show, NYC.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, 30 March 2022.

0 notes

Photo

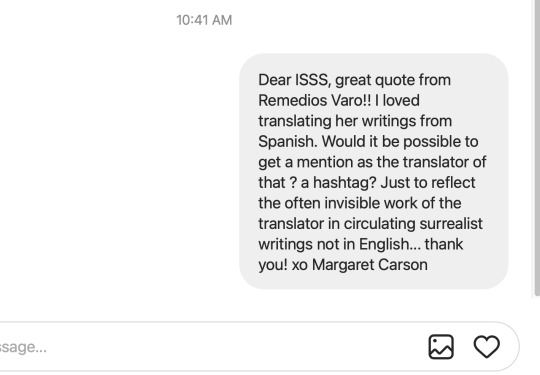

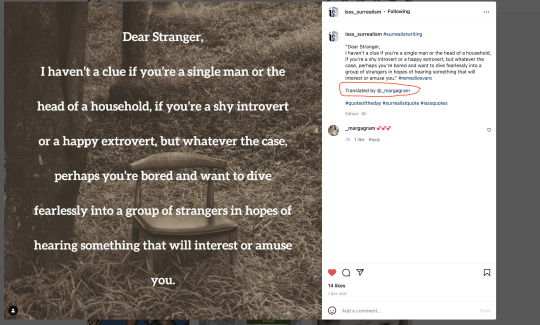

Time Out for Translator Advocacy! The gentle art of asking for a translator shout-out….Happy to report that the translator’s name has been added!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Tumblr Became Popular for Being Obsolete https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/how-tumblr-became-popular-for-being-obsolete

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

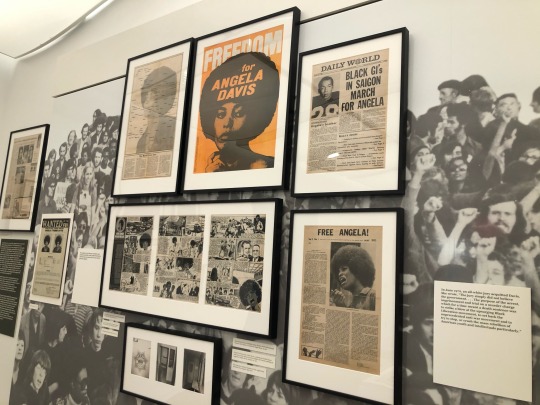

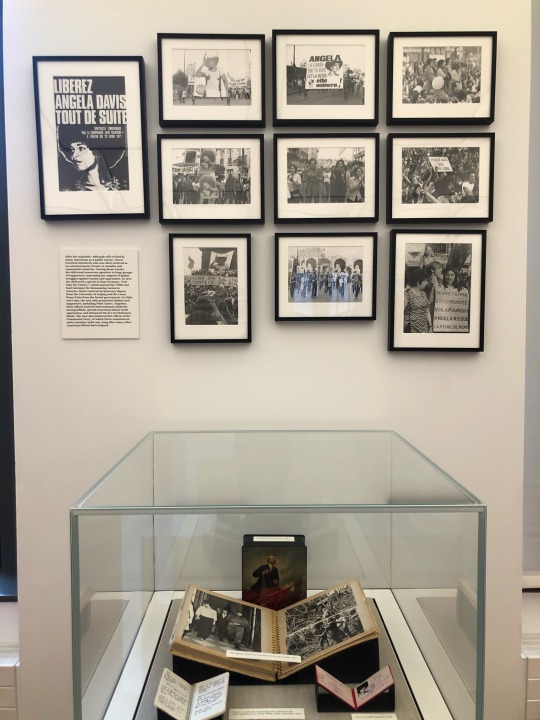

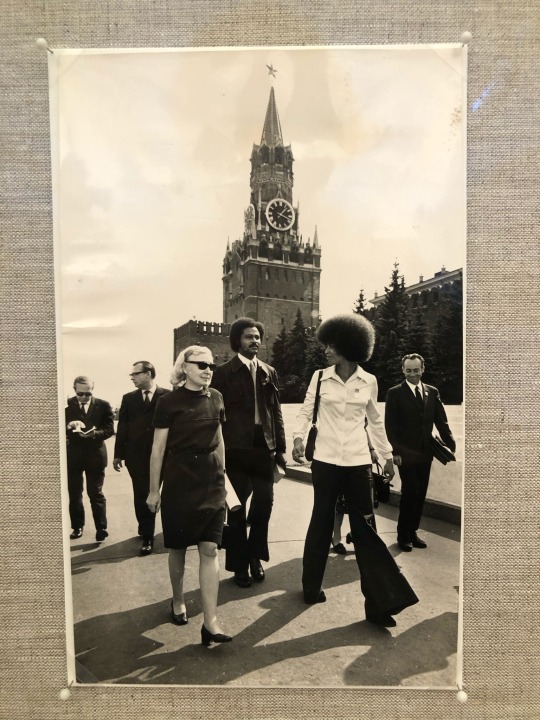

If you haven’t already—check out the Angela Davis exhibit I helped curate at the Schlesinger Library. Angela Davis: Freed by the People runs through March 9, 2020. The crown jewel of the collection is the manuscript of Angela’s autobiography with edits from Toni Morrison.

Here I am with Angela and my brilliant and fierce student Salma!!

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

#WiT Goes to Senate House, London: Notes from the “Translating Women” Conference 31 Oct. - 1 Nov. 2019

Part I

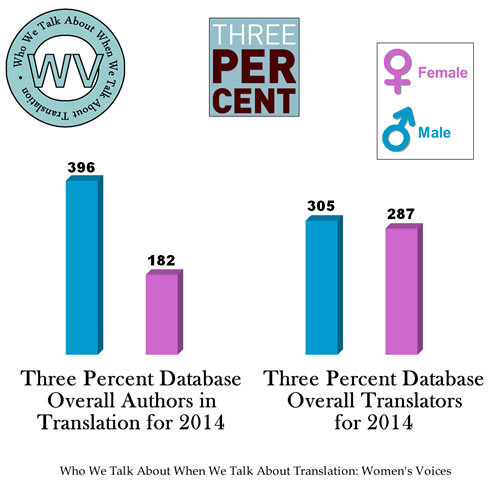

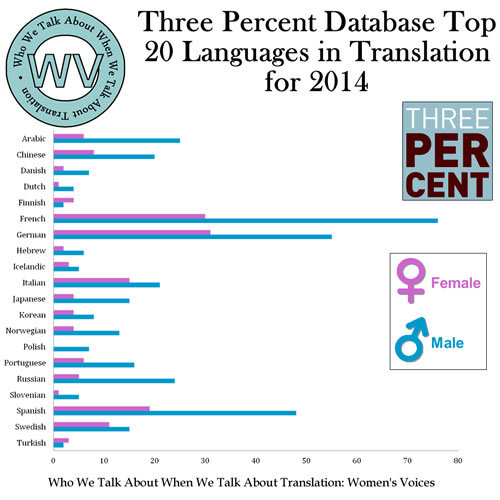

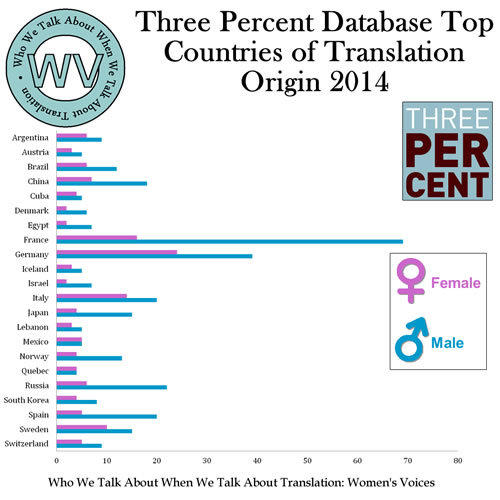

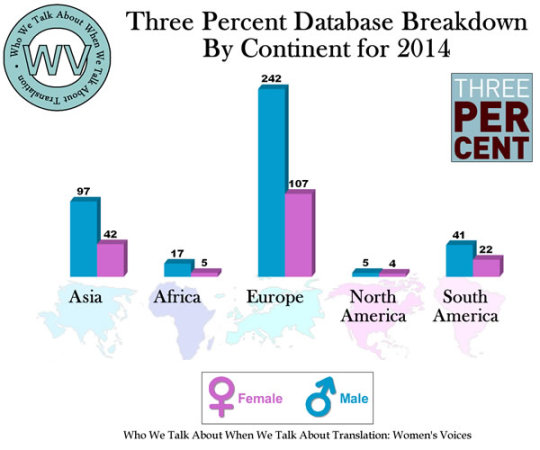

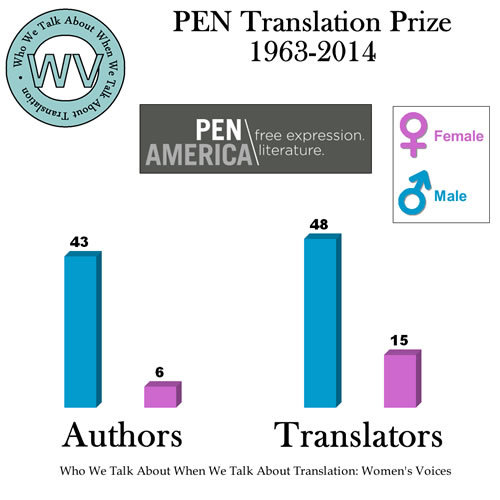

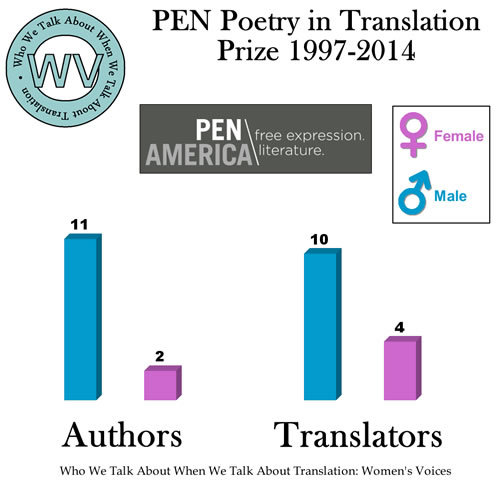

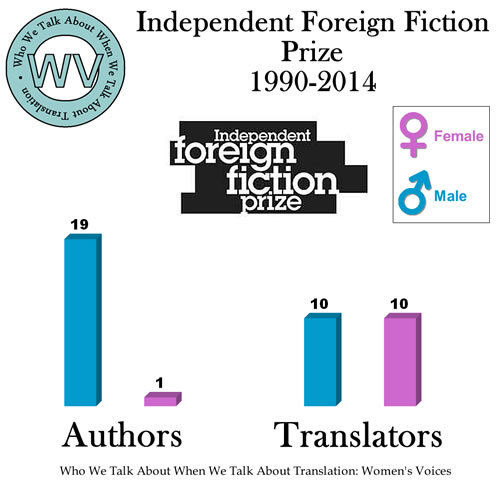

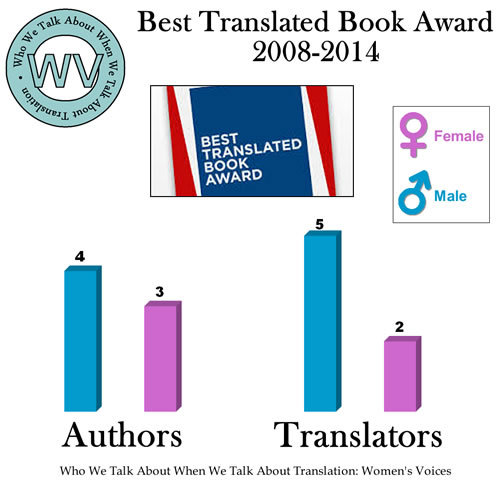

Being a WiT activist can take you to some extraordinary places. In my case, to Senate House, University of London, in the heart of Bloomsbury and right across from the British Museum, for the first-ever conference devoted to women, translation and literary publishing: “Translating Women: Breaking Borders and Building Bridges in the English-Language Book Industry,” organized by the #WiT activists and scholars Helen Vasallo (U Exeter) and Olga Castro (U Warwick) and hosted by The Institute for Modern Languages Research. As the keynote speaker I had the immense pleasure of kicking the conference off for the over 70 attendees in a talk I called “Snap! The Whys and Hows of Women in Translation”— “Snap!” being philosopher Sara Ahmed’s term in Living a Feminist Life for that critical moment, that pressure point, that can be the start of a pushback. I recounted how Alison Anderson’s posting on Words Without Borders in May, 2013, “Where Are the Women in Translation?” jolted many translators out of our complacent sense that all was forward-thinking and good in the Republic of Translated Literature. Anderson was the first to point out in print the significant gender imbalance in translation. Following the lead of VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, she used the 3% Database (set up in 2008 by Chad Post of Open Letter Books, and now housed at Publishers Weekly) to establish that only 26% of the books of fiction or poetry in translation published in the US were by women. She also pointed to the near-invisibility of women authors in translation on literary prize longlists and shortlists and to their near-absence as prizewinners, singling out the International Foreign Fiction Prize as what I’d call an especially noxious bastion of male dominance—only 2 women writers won in its 17 or so years of existence. That was Anderson’s Snap! moment. Mine was to follow.

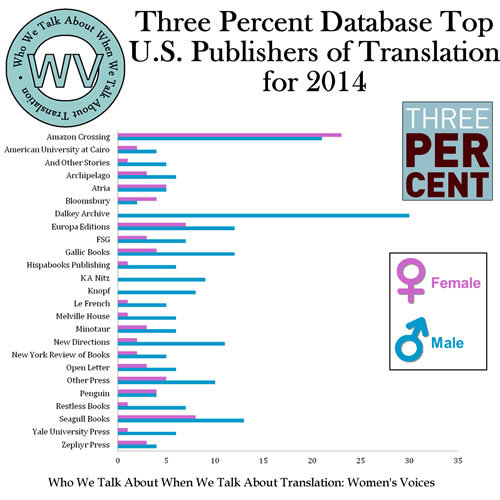

With Anderson’s article in mind, I used the same freely available dataset to see how the biggest publishers of translations fared when gender of the author was taken into consideration. In other words, doing the full VIDA Count, but breaking out these variables: gender by original language, by country of origin, and by US publishers of translations. (Blogger and tweeter extraordinaire Meytal Radzinski—aka @bibliobio @ReadWIT—had also been crunching the same database, and came out with similar results.)

With respect to US publishers, in the most extreme case, I saw that in 2014 Dalkey Archive Press and its legendary editor John O’Brien had published not one single woman author out of its 30 titles in translation that year. Mr. O’Brien: What kind of enlightened and innovative editorial vision is that? A further offense: my tax dollars have gone into funding the NEA, a major grant-provider for your sexist press. Snap!

Did the negative publicity around this outrageous disparity nudge Dalkey into the 21st century? I’ve noticed that their list now never fails to include some women in translation (but nothing close to parity)—perhaps a concession to the threat of government funding—a lifeblood for non-profit presses—being denied.

To underscore, I speak from the perspective of a translator. It’s a rough terrain out there. Translation gigs are extremely competitive and one feels some pressure as a translator to “make nice” to publishers in the insular world of English-language literary publishing in order to stay in the game.

Nevertheless—persistence!

The provocations I ended my talk with are:

— When you write articles or speak on translation, cite women. Click here for a bibliography in progress of book-length works or essays on translation authored by women. It’s a list that incorporates many recommendations made by my translator colleagues.

—Question and challenge canons. I’d like to drop the idea of a “canon’ once and for all. It’s an example of adopting the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house (in Audre Lorde’s terms). Delegitimize the notion of a canon.

—Don’t become a marketing tool for publishers.

—Watch out for “women in translation light,” for example, holding a reading under that banner but not talking about gender and other imbalances in translation. It will soon turn into an empty slogan.

I’m deeply grateful to Helen and Olga for inviting me to do the keynote—an enormous privilege—and I hope it helped set the stage for the wide spectrum of presentations and dialogues that followed over the next two days, a report on which is TK….

[End of part I of “Notes from the “Translating Women” conference.]

Margaret Carson

#TWConf19#helen vasallo#olga castro#sara ahmed#Senate House#WiT#Alison Anderson#Snap!#meytal radzinski

1 note

·

View note

Video

tumblr

Argentine writer Ariana Harwicz recounting a testy moment with her French translator: Harwicz told her, don’t clean up the word “deportar” in translation, I want “deport” not “expel,” i.e., I want to make sure the association with round-ups and being sent to concentration camps comes through in the translation. During the “Translating Women” conference #TWconf19. Senate House, University of London, 31 Oct - 1 Nov. 2019.

0 notes

Text

The Broken Chandelier

The translator twitterverse exploded last Friday after the Los Angeles Review of Books published Magdalena Edwards’ incendiary article about a translation gone awry, “Benjamin Moser and the Smallest Woman in the World.” An insider’s account of her experiences working with Benjamin Moser and New Directions as the translator of Clarice Lispector’s The Chandelier, Edwards’ narrative paints a grim picture of what would otherwise seem like a stellar project—to work on a previously untranslated novel by an internationally renowned writer, as part of a well-received series put out by a prestigious publisher. As Edwards relates it, a cordial long-distance acquaintance formed with series editor Benjamin Moser over their shared interest in Lispector, Elizabeth Bishop, and translation was a prelude to being asked to take on the project in 2015. Things quickly turned sour, however, after Edwards sent her draft translation to Moser in the summer of 2017. “The truth is that Moser tried to get me fired, arguing that my completed manuscript was not up to snuff, that my level of Portuguese was insufficient, and that he would have to rewrite every line of my translation. What happened?” she asks, drawing us into the messy tale that follows.

Her account is a rare instance of a translator parting the curtains to reveal behind-the-scenes dealings with an editor and a publisher over a contested translation. While Edwards goes on to make a larger argument against Moser, giving instances of his borrowing from the work of others, almost all women, without giving credit, I’m especially attuned to the “wrongs” of this particular translation project and wondered what conditions made such a situation possible. Based on Edwards’ account and my own reading between the lines, I understand the following: Yes, there was a contract, and it was strictly between the translator and New Directions. No, it had no provisions setting the terms of the working relationship between the translator and the outside series editor, who appears to have been given carte blanche in overseeing the series. No, there were apparently no revisions made to the contract to reflect the fact that the outside series editor (Moser), not the publisher (New Directions), would deem the manuscript acceptable or not. No, there were apparently no specific provisions about what an acceptable translation would be, giving the publisher, or rather, in this exceptional case, the outside series editor, lots of wriggle room. Barbara Epler of New Directions seems to have deferred to Moser’s judgment in offering Edwards a “kill fee” i.e., thank you for your trouble, good-bye. But before offering the kill fee—something not in the contract and improvised by the publisher as a way out— did Epler ask Moser for some justification? Was any outside reader asked to look over the translation and weigh in? Or was it simply a matter of Moser’s word and his steamrolling vision of how Lispector had to read in English?

After experiencing typical translator shame (“I was flustered and apologetic”) after Moser trashed her translation and Epler sent her an email with the offer of the kill fee, Edwards wisely consulted a lawyer and began to push back hard against the steamroll.

So yes, there’s a legal side to this, and Edwards’ informed resistance most likely kept her from being completely erased on the title page upon the book’s publication. In the end, Edwards was credited as “co-translator,” with Moser’s name first (they’re not even in alphabetical order). I see it as a perverse kind of credit, a non-thanks for her work, to be joined there with the person who wanted her kicked off the project.

Pure speculation: if Edwards had agreed to such an absurdity as a kill fee, what would have happened next? Would Moser have in truth retranslated every line of the original, starting from scratch? Or would he have leaned on Edwards’ existing translation? The second half of Edwards’ article makes the latter seem plausible.

If there was any doubt about Moser’s overstepping his role as editor, consider the bio-note he submitted to the New York Times to run with his review of Kate Briggs’ This Little Art. Since his takedown review attracted unusual interest among translators, many noticed that he’d given himself full credit for translating The Chandelier and hastened to alert the New York Times via Twitter, myself among them. (The Times quickly corrected it, as Edwards notes).

By way of comparison, I recall another multi-volume project that involved several translators working under a series editor to translate a single author: the massive retranslation of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu/In Search of Lost Time. In her “Note on the Translation,” Lydia Davis, who retranslated Swann’s Way, depicts a radically different working atmosphere for the crew of Proust translators:

“At the initial meeting of the Penguin Classics project, those present had acknowledged that a degree of heterogeneity across the volumes was inevitable and perhaps even desirable, and that philosophical differences would exist among the translators. As they proceeded, therefore, the translators worked fairly independently, and decided for themselves how close their translations should be to the original—how many liberties, for instance, might be taken with the sanctity of Proust’s long sentences. And Christopher Prendergast [the series editor], as he reviewed all the translations, kept his editorial hand relatively light.” (emphasis mine) Swann’s Way, xxi-xxii.

It’s true that no two translation series are alike, and for sure no two editors are alike, but as a translator it was profoundly disturbing to read Edwards’ account. In a brave move, she stopped being a “nice girl” going along with the flow and stood up to the bully in this scathing public indictment. One wonders if there will be any response.

—Margaret Carson

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A WiT End-of-Year Highlight

How better to mark the news of Amazon’s future HQ2 in Long Island City, New York than by reading Seasonal Associate, Heike Geissler’s account of her soul-crushing stint working at an Amazon fulfillment center in Leipzig, Germany, translated by fellow WiT activist Katy Derbyshire? The book’s publication in early December followed fast on reports of the trillion-dollar behemoth’s enraging tax-credit-enhanced deal with New York City’s Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Mario Cuomo—an example of corporate welfare at its most repellent, with zoning exceptions thrown in for helipads and the like. Seasonal Associate offers us the real stuff: an up-close view of the endlessly repetitive scanning, logging, stowing, crating, stooping that makes Amazon what it is— “the work that leaves the employee no space to be human,” in Geissler’s (or Derbyshire’s) words.

The book has been widely reviewed in:

The New Yorker

Bookforum

The New Republic

The Nation

Harper’s Magazine

The Christian Century

Special kudos to Katy Derbyshire, who went unnamed, or at best, briefly mentioned, in the body of these reviews. Her sparkling Translator’s Note—as accomplished as her translation and also largely ignored by reviewers—provides the reader with the book’s essential back story and recounts its improbable journey toward publication, first in Germany and now in the US. (We remember seeing it back in 2016 on Lit Hub’s 10 German Books by Women We’d Love to See in English, the first in an essential series curated by Derbyshire that updated the “Translate Me!” concept for women authors, truly a WiT milestone!) And to add insult to injury, one reviewer even cribbed ideas from Derbyshire’s Note without the slightest hat tip: Alex Press in The Nation opens his review with an account of one of the many “Working at Amazon” videos uploaded to YouTube—something Derbyshire writes about discovering and mining for their rich details while doing her translation. Alex Press: why not simply say who pointed you to the videos? It’s highly doubtful you knew about them on your own… :((

Here’s hoping for more WiT highlights (and much improved recognition for translators) in 2019!

3 notes

·

View notes

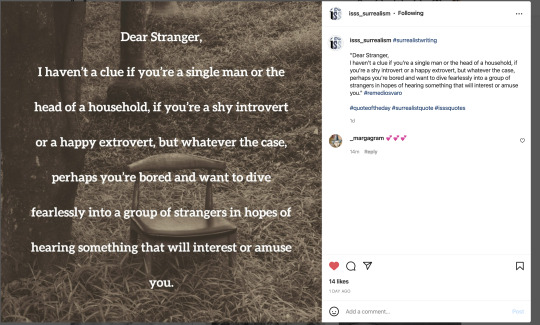

Quote

Dear Stranger, I haven’t a clue if you’re a single man or the head of a household, if you’re a shy introvert or a happy extrovert, but whatever the case, perhaps you’re bored and want to dive fearlessly into a group of strangers in hopes of hearing something that will interest or amuse you. What’s more, the fact that you feel curiosity and even some discomfort is already an incentive, and so I’m proposing that you come and spend New Year’s Eve at house No.—— on —— Street … I’m merely invited to go there, as are a handful of other people, so in order to attend you should call xxx-xxxx ahead of time and ask for Señora Elena, firmly declare that you’ve met before, that you’re a friend of Edward’s, and that, feeling lonely and blue, you’d like to go to her house to ring in the New Year. I’ll be among the guests and you’ll have to guess which one of them is me.

Remedios Varo, Letters, Dreams & Other Writings, translated by Margaret Carson (Wakefield Press), as excerpted on The Paris Review Daily. (via womenintranslation)

3 notes

·

View notes

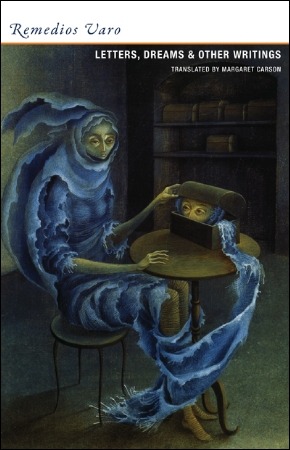

Photo

Varomania, part I 😍😘💙

Another triumph of 2018: the publication of two new translations of Surrealist literature, adding significant female voices to the canon. Even if you missed the Surrealism with Margaret Carson and Mary Ann Caws event at Book Culture on 112th in late November, you can still dive into the books.

From the Wakfield Press announcement of Margaret Carson’s translation of Remedios Varo:

While the reputation of Remedios Varo the Surrealist painter is now well established, Remedios Varo the writer has yet to be fully discovered. Her writings, never published during her life let alone translated into English, offer the same qualities to be found in her visual work: an engagement with mysticism and magic, a breakdown of the border between the everyday and the marvelous, a love of mischief, and an ongoing meditation on the need for (and the trauma of) escape in all its forms.

From the New Directions announcement of the collection edited by Mary Ann Caws:

Here are the gems of this major, mind-bending aesthetic and political movement: works not only by Aragon, Breton, Dalí, René Char, and Robert Desnos, but also by key, often overlooked female Surrealists—Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Mina Loy, Alice Rahon, Gisèle Prassinos, and Kay Sage. The Milk Bowl of Feathers provides a grand picture of this revolutionary movement that shocked the world.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Initial data … Vexed? We are, too! This situation is much more complex than it looks, so this is just the beginning. We look forward to seeing many of you at tomorrow’s panel, and to continuing the conversation afterward.

4 notes

·

View notes