Photo

Bee Dances, 2001-Present Sarah Mapelli (aka BeeQueen) USA

It’s sensual. At the same time, you know there’s this fierceness - Mapelli in an interview with National Geographic

Sarah Mapelli is an artist, healer, helper, bee dancer and builder. In 2001 she contacted entomologist Michael Burgett [of Oregon State University] for help realizing a vision of dancing while covered in bees. He provided her with a pheromone mix of “ the scent of 1,000 queens” which caused a swarming hive of bees to latch on to her. In later performances, she switches to wearing a hives queen around her neck in a small cage (or “spaceship” as she likes to call them).

Her first dance lasted 2 hours and took the form of a photoshoot. Mapelli’s dancing is fantastically fluid, a meditation guided by bees. She listens to the bees need for warmth, moving slowly and carefully as not to aggravate them. Mapelli and 12,000 bees dance in a fierce and intimate duet. But even though the experience was loud and slightly painful, she’s been dancing with bees ever since. She’s received a moderate amount of media coverage and is featured in the film Queen of the Sun: What are the Bees Telling Us?

Many of her performances focus on healing - the audience sits in two circles, an inner one and outer one while Mapelli dances, moving from person to person. Some - especially those on her youtube channel - feature others in an improvisational and collaborative dance. Mapelli views her dances as always collaborative: it’s her and the bees dancing together - with the bees leading. She hopes that by dancing in unison with so many bees that she can show others that bees aren’t something to be afraid of.

In an interview with BellaMia magazine in 2016, Mapelli is quoted as saying “I don't want to personify the bee world. I want to help bee-ify the person world.” The notion of learning from bees runs deep in Mapellis work and she often focuses on human communities in her writings. Moreover, her architecture practices is very inspired by bee hive construction.

we have self-pollination cross-pollination wind-pollination. It’s not enough at the rate in which we trade habitat for the habit of economic growth to debate Each one of us is hypocrite the monster is so big we are tumbling down. so help the pollinators grab some higher ground

Each one of us pollinates as we move amongst each other. In conversation, communication, In contact we embrace constantly transversing, transferring, motion and magnetism feet on the surface electric below Earth's terrestrial ecosystem will continue to grow

- Excerpted from the artist’s blog

Mapelli’s work is also staunchly anti-capitalist and pushes against the destruction of natural bee habitats for profit. She calls for more collaborative and communal living spaces and employment. You can read more here on her website.

I was initially introduced to Sarah Mapelli through @inthenow on tiktok. You can buy merch from Mapelli here, on her Zazzle Store.

#performance art#sarah mapelli#bees#2000s#2010s#bee#insect#dancing#healing#energy#anti-capitalism#communism#communal living#energy healing#nature

488 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shoot, 1971 Chris Burden Santa Ana, California

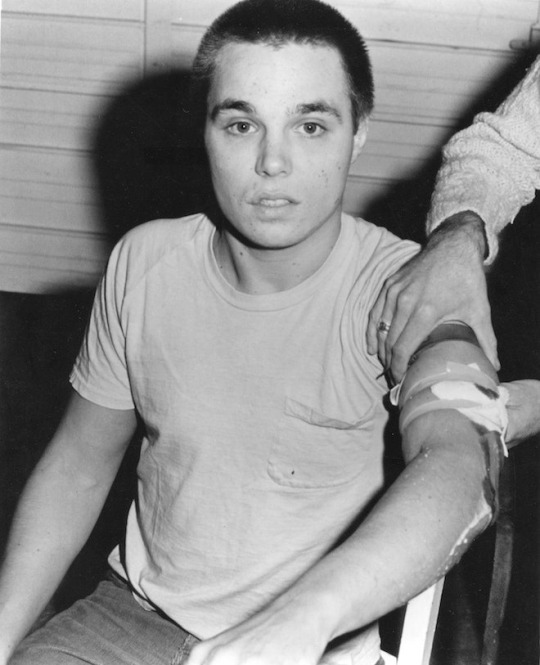

At 7:45 p.m. I was shot in the left arm by a friend. The bullet was a copper jacket 22 long rifle. My friend was standing about fifteen feet from me.

“Burden asked his friend, Bruce Dunlap, to shoot him in the arm with the instruction that the bullet should just graze his skin. He also arranged with his wife, Barbara Burden, to film the action on a Super 8 camera; with his friend, Alfred Lutjeans, to take photographs; and with fellow artist Barbara T. Smith to make an audio recording.” [1] These can be can be viewed on youtube. Burden is know to have "carefully staged each performance and had [them] photographed and sometimes also filmed; he selected usually one or two photographs of each event for display in exhibitions and catalogs .... In this way, Burden produced himself for posterity through meticulously orchestrated textual and visual representation” [2]

“In addition, he invited a small group of people to watch the performance. ... Burden followed through with his plan and was shot in the left arm by Dunlap, who was standing fifteen feet away from him. However, while the bullet was intended to just nick Burden’s arm, in the performance, it passed through his arm instead, causing a more substantial wound.” [1]

“Although Shoot has been described as intrepidly ‘death defying,’ it challenges any sense of mastery. As a young man of draft age during the Vietnam War, Burden certainly could be seen as attempting to perform the heroic masculinity associated with the figure of the soldier who survives and overcomes in the face of gun fire. Twenty years after the event, Burden would describe Shoot as an attempt to gain control over a threatened injury. Noting that ‘being shot, at least in America, is as American as apple pie,’ Burden described his performance as undertaking ‘to do it in this clinical way, to do something that most people would go out of their way to avoid, to turn around and face the monster and say, ‘Well, let’s find out what it’s about.’’ Yet, rather than asserting Burden’s invincibility, Shoot exposed his vulnerability. In a photograph of Burden just before the trigger was pulled, one sees a young man standing squarely with his feet apart, his shoulders back, and his chest out; his arms are held slightly away from his body. In this stance, he looks simultaneously broad and commanding and as though he is nervously holding the target for the bullet (his arm) away from the core of his body. He reads as sturdy and trembling at once. Contemplating Shoot in the context of the Vietnam War, we might see it not as reinforcing or uncritically celebrating the myth of an inviolable masculinity so much as a reminder that such notions have been mobilized in the context of war precisely in order to prepare young men for placing their bodies into positions of vulnerability. In the end, rather than mastering the threat of being shot by orchestrating a faceoff from which he would walk away with a grazed wound, Burden found himself coping with an injury for which he was not prepared. As he put it, “we didn’t even have any band-aids.” this lack of foresight could be attributed to hubris or naivety on Burden’s part, but regardless, it is also part of the piece. One needs only to look at a photograph of Burden after he was shot to see in his glazed over eyes and slackened jaw a look that con)rms that Burden was not fully in charge of this experience.” [1]

Sources: [1]: Performing Endurance: Art and Politics since 1960 [Link] [2]: The Performativity of Performance Documentation [Link]

#chris burden#shoot#performance art#gun#1971#1970s#vietnam war#santa ana#california#film#body art#masculinity#femininity#misogyny#rifle#arm

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Good at Shooting, Bad at Painting Khaled Jarrar, 2018

Invoking the CIA's efforts to use abstract art as a pro-american and anti-communist propaganda tool, Jarrar fired an AR-15 to shatter small bottles of paint on to a cloth canvas while seated at an office desk. The audience was invited to give pieces of their clothing to Jarrar so that he could affix them to the canvas, paint them and assign them serial numbers before returning them to the person who cut them off their clothes. After mounting them to the canvas, Jarrar shot pairs of paint filled bottles over and over and over while seated leisurely sitting at an office desk dressed in business attire, sipping coffee and eating a donut.

“Gently I press the trigger, the bullet capable of reaching hundreds of meters in less than a second. Pressing it is always sensitive and fragile; it is like touching something that has never been touched before. Undoubtedly, the bullet will go fast and hit the target to create colorful shapes, exposing how powerless we can be if we are within its frame. I try to engender a methodology that allows me to create art where I can use the skills that I learned as a trained soldier. This methodology is a space of metaphors, displaying a natural analogy of my accumulated skills as both artist and soldier. I was trained to shoot, to follow rules, and I was good at it.” [Khaled Jarrar, Ⱥ]

Above images are excerpted from a video of the performance on youtube.

#2010s#2018#khaled jarrar#shooting#guns#abstract art#cia#clothing#paint#painting#propaganda#ar-15#video available

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood For Sale Khaled Jarrar, 2018, New York

For four days Khaled Jarrar attempted to sell 50 10mL vials of his own blood on the corner of Wall Street and Broad Street in the Financial District of New York, USA. The vials were contained in a cooler hanging from the artists neck and were priced according to the stock prices of American defense contractors. He also had an associate that was yelling “10 milliliters of fresh artist blood” like a paperboy.

The first eight vials were priced at $19.48 directly referencing the 1948 Palestine War and the forced expulsion of two-thirds of the local population in Palestine by zionist militias. The remaining 42 vials were priced based stock prices of America's most prominent defense contractors. The final and most expensive of the vials were priced at roughly $347, the cost of one Lockheed Martin stock. Each vial sold comes with a signed and editioned certificate written in Arabic.

The vials

went to friends and followers of his work, though the majority of buyers were passersby: curious tourists, Pro-Palestinian investment bankers, at least one Trump Tower employee. Others have offered to donate money or pay for just the certificate. Jarrar says he turns them down. “I say, no. You have to hold the blood in your hands,” he explains. “You pay the price for the pain.” [News coverage from Art Net]

Although local businesses called the police, the performance was eventually allowed to proceed as planned. All proceeds of the sales were donated to hospitals in Yemen and Gaza.

[Images from the Open Source Gallery]

#new york#2010s#2018#palestine#original description#khaled jarrar#blood#stocks#war#performance art#stock market

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[unknown title] boychild, 2013

Performances by boychild are sci-fi in aesthetic and nature. boychild uses posthuman performance strategies to communicate meaning through combinations of body, voice and technology. boychild's performances often reference idea of cyborgs, which plays with the hybrid of machine and organism and becomes a creature of social reality and fiction [Source: Wikipedia]

The above images are excerpted from two of boychilds performances to Say My Name (Cyril Hahn remix) which can be found here and here.

#boychild#2010s#2013#performance art#dance#surreal#surrealism#sci-fi#science fiction#posthuman#rave#lights#trans#queer artist

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seedbed Vito Acconci, 1972, New York

"In this legendary sculpture/performance Acconci lay beneath a ramp built in the Sonnabend Gallery. Over the course of three weeks, he masturbated eight hours a day while murmuring things like, "You're pushing your cunt down on my mouth" or "You're ramming your cock down into my ass." Not only does the architectural intervention presage much of his subsequent work, but all of Acconci's fixations converge in this, the spiritual sphincter of his art. In Seedbed, Acconci is the producer and the receiver of the work's pleasure. He is simultaneously public and private, making marks yet leaving little behind, and demonstrating ultra-awareness of his viewer while being in a semi-trance state." [Source: Ubu.com]

Born in the Bronx into a Catholic Italian family, the overprotected only son of a bathrobe manufacturer and a mother who later worked in a public-school cafeteria, Mr. Acconci came of age in the politically agitated years when artists began trying to find ways around the making and selling of objects. They turned to their bodies, their ideas and their actions as the currency of a new realm. Along with peers like Chris Burden, Adrian Piper, Dan Graham and Valie Export, Mr. Acconci began conceiving and documenting performances — at a rate of sometimes one a day in what he called “a kind of fever” in 1969 — that were conducted on the streets or for audiences so small that they seemed almost not to have happened. [Source: The New York Time (2016)]

Images excerpted from a video of the performance, which can be found here at ubu.com.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain was created on May 11, 1995. According to Zhang Huan's associate Kong Bu, the project began at 13:00 with two surveyors, Jin Kui and Xiong Wen, setting up their equipment to measure the height of the Miaofeng Mountain, which was 86.393 meters. Then the ten naked artists lined up by ascending weight, and with the heaviest at the very bottom, they lay on top of each other in the form of a pyramid. The artists eventually constituted five layers: three people in the bottom layer, two people in each of the three middle layers, and one person lying at the top. In the meantime, the surveyors kept tracking the total height. Between 13:26 and 13:38 that afternoon, their measurement came to 87.393 meters, precisely one meter higher than the original height.

In the mid-1980s, under the influence of western modernist and postmodernist art forms which were introduced to China after the Chinese economic reform, a group of Chinese visual artists started to experiment with conceptual performance art. Through such art form, they showed their intention to “move out of the state-controlled gallery system” and "act out" their art in the public sphere.

In the early 1990s, an avant-garde artistic community called “the Beijing East-Village” emerged on the urban edge of Beijing. Living in shelters built up for migrant workers, the small group of artists from different parts of China gathered and created collaborative performance work in and around the area. Zhang Huan, Zhu Ming and Ma Liuming, the leading artists of the community, mainly focused their works on exploring and reflecting “gender, sexuality, and physical and psychological endurance.” To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain is one of the performance works done by Zhang Huan during this time period.

[Source: Wikipedia]

To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond was a work in a similar vein conceived and directed by Zhang Huan. Approximately forty migrant laborers, all males ranging in age from 4 to 60, naked to the waist, walked into a Beijing fish pond together in order to raise the water line through their shared body mass. While raising the water level this group of peasants also raise awareness of, and give voice to their unnoticed community of itinerant workers. [Source: The Met]

Zhang Huan, To add one meter to an anonymous mountain, 1995

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vito Acconci (1940–2017)

TRADEMARKS Photo piece, 1970

Biting myself: biting as much of my body as I can reach.

If someone passionately embraces his double through the glass, at that moment the double becomes alive, and the being and the image love one another through the wall. —Alfred Jarry, Les Jours et Les Nuits, 1897

Vito Acconci was one of the first to experiment with performance art, in which the artist’s own body was treated like clay—a material to be manipulated, altered, posed, punished, and displayed. In Trademarks, Acconci established a task to execute and then performed it diligently, biting as many parts of his naked body as he could reach and documenting his self-mutilation with photographs and printer’s ink. Like much of his work, Trademarks seeks to breach the boundaries between inside and outside, private and public. The work is also intended as an astute, even humorous, commentary on the branding and marketing of artists and their labor.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cut Piece Yoko Ono, 1964

“”” Cut Piece First version for single performer:

Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage—one at a time—to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option. “““

In a second version, Ono amended the instructions slightly, indicating that “members of the audience may cut each other’s clothing. The audience may cut as long as they wish.”

In Cut Piece—one of Yoko Ono’s early performance works—the artist sat alone on a stage, dressed in her best suit, with a pair of scissors in front of her. The audience had been instructed that they could take turns approaching her and use the scissors to cut off a small piece of her clothing, which was theirs to keep. Some people approached hesitantly, cutting a small square of fabric from her sleeve or the hem of her skirt. Others came boldly, snipping away the front of her blouse or the straps of her bra. Ono remained motionless and expressionless throughout, until, at her discretion, the performance ended. In reflecting upon the experience recently, the artist said: “When I do the Cut Piece, I get into a trance, and so I don’t feel too frightened.…We usually give something with a purpose…but I wanted to see what they would take….There was a long silence between one person coming up and the next person coming up. And I said it’s fantastic, beautiful music, you know? Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Beautiful poetry, actually.”

Ono debuted Cut Piece in Kyoto, in 1964, and has since reprised it in Tokyo, New York, London, and, most recently, Paris in 2003. It is the realization of what she calls a “score,” a set of written instructions that when followed result in an action, event, performance, or some other kind of experience. As with most of her work—which also encompasses music, poetry, film, sculpture, installation, paintings, and events—the participation of others is often key. Equally conceptual and physical, Cut Piece relies upon audiences’ willingness to interpret and follow the instructions outlining their role. Though participatory art is now more common, Ono was among its pioneers. In works like Cut Piece, she invites viewers to become agents in the creation of art.

Cut Piece has inspired numerous (often conflicting) interpretations, including those offered by the artist herself. In 1967, for example, she described it as “a form of giving, giving and taking. It was a kind of criticism against artists, who are always giving what they want to give. I wanted people to take whatever they wanted to, so it was very important to say you can cut wherever you want to. It is a form of giving that has a lot to do with Buddhism.…A form of total giving as opposed to reasonable giving….”

[Text from the MoMA website, Archived Link]

A portion of the performance can be found here on youtube and this archived link. Images above are excerpted from this video.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self-Portrait/Pervert, 1994 Catherine Opie, Chromogenic print 40 inches x 29 7/8 inches (101.6 x 75.9 cm)

Self-Portrait/Nursing, 2004 Catherine Opie, Chromogenic print 40 x 31 inches (101.6 x 78.7 cm)

Self-Portrait/Cutting, 1993 Catherine Opie, Chromogenic print 40 inches x 29 7/16 inches (101.6 x 74.8 cm)

“”” Since the early 1990s Catherine Opie has produced a rich, complex photographic oeuvre that explores notions of communal, sexual, and cultural identity. From her early portraits of queer subcultures, pristine urban panoramas, and expansive landscapes to incisive views of her own domestic life, Opie has offered profound insights into the conditions in which communities form and the terms in which they are defined. Throughout her career, self-portraiture has served as a marker of personal and artistic development, as well as a reminder that she, as the photographer, does not stand apart from the groups she documents. In this vein, she made Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) and Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994) alongside her renowned series portraying fellow members of San Francisco’s queer leather subculture. Like those images, her self-portraits address contemporary concerns of queer identity, while couching their content in a formal tradition recalling the sixteenth-century paintings of Hans Holbein. In these images Opie offers something deeply personal, even confessional, revealing powerful longings that are compounded by the great physical vulnerability of the sadomasochistic acts the photographs document. Ten years later, in Self-Portrait/Nursing (2004), Opie returned to the genre, newly suffusing her image with a sense of rapturous contentment, as she holds her infant son in a classically maternal pose that further evokes art-historical imagery. Faintly but clearly visible on her chest, the word “pervert” still appears as a scar, a trace of her history that carries forward through time. “““

[Text and images from the Guggenheim website]

408 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dahlia and David (fag with a scar that says dyke), 2019 Presented as an archival pigment print

Photographed by Elle Pérez as part of a [set of photographs] depicting queer love.

From one of the artists/subjects twitter:

"Dahlia and David (fag with a scar that says dyke)" is both personally significant and a beautiful way for Dahlia and I to enshrine 5(?!) years of kinship and play.

for Dahlia, sadomasochism is an art form, and i think i can speak for both of us when i say that for both of us it is also our primary means of sharing intimacy, care, and self-expression.

[Source, Archived Version]

[Image Source]

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I only used the one image which presents the strongest moment of the performance itself, and can therefore stand on its own as a photograph… . The audience can, by reading the text description, and by looking at one single photograph, imagine the rest in their minds. -– Marina Abramovic Interested in the limits of mental and physical endurance, influential performance artist Marina Abramovic has used her body as the subject and medium of her work since the early 1970s. Though not her medium directly, photography has also played an important part in her career, documenting performances and so providing the only extant time-based traces of those temporal acts. The series Performance Edition 1970-75 uses one photograph and one text panel each to represent performances for which there no longer is (or never was) film or video documentation. The text of Lips of Thomas explains that 1973 performance:

LIPS OF THOMAS Performance I slowly eat 1 kilo of honey with a silver spoon. I slowly drink 1 liter of red wine out of a crystal glass. I break the glass with my right hand. I cut a five pointed star on my stomach with a razor blade. I violently whip myself until I no longer feel any pain. I lay down on a cross made of ice blocks. The heat of a suspended space heater pointed at my stomach Causes the cut star to bleed. The rest of my body begins to freeze I remain on the ice cross for 30 minutes until the audience interrupts the piece by removing the ice blocks from underneath. Duration: 2 hours 1975 Krinzinger Gallery Innsbruck

[Text and image from the Museum of Contemporary Photography]

999 notes

·

View notes

Text

“““

ORLAN (born Mireille Porte) is a French contemporary artist best known for her work with plastic surgery in the early to mid-1990s. ORLAN is known as a pioneer of carnal art, a form of self-portraiture that utilizes body modification to distort one's appearance. She adopted the pseudonym "ORLAN" in 1971, and capitalises each letter because, as ORLAN states, she has 'no desire to step back into rank.’ She lives and works in Paris.

She practices painting, sculpture, photography and video, and produces plastic works, installations and performances. She also uses digital media, surgery, medicine, robotics, AI and biotechnologies. ORLAN says that her art is not body art, but rather 'carnal art,' which lacks the suffering aspect of body art.

ORLAN's performance artwork uses famous depictions of women by male artists, for example, Mona Lisa and Jean-Léon Gérôme's artwork depicting a woman with horns, to inform her surgery choices and performance art. By doing so, ORLAN is replicating ideal features of women depicted in famous artwork throughout time, on her own body and face. ORLAN says that she has been troubled by the nude depictions of women in artwork throughout history, who were there only to satisfy the male gaze, which is why she is attempting to change this in a powerful and revelatory way, by challenging the conventions women are forced to conform to.

“““

[from wikipedia]

French performance artist Orlan, whose work consisted of livestreaming a series of cosmetic surgeries to give her the ideal face composed of five classic features of fine art, including forehead of the Mona Lisa and the chin of Botticelli's Venus

1K notes

·

View notes