they/them | this blog gives entry level answers (where possible) to questions about language and linguistics for people who don't have a background in it

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

Multiple-question anon here! I found the answer to my other question so thats why theres only one. But I saw that joke you reblogged. What does 'phonemically contrastive environments' mean?

This is the post anon is referring to

Also have a question about something language related? Check out my ask guidelines here.

Quick note on my IPA transcriptions: I was taught a General American accent and IPA alongside that, so I tend to default to that when transcribing English words, unless I'm explicitly talking about other varieties of English.

What is a Phonemically Contrastive Environment?

To start with the basics, a phonemically contrastive environment has to do with phonemes.

A phoneme is a specific category of speech sound. The phonology of a language is made up of several phonemes (consonants and vowels). Specifically, though, a phoneme is a contrastive sound. They can change the meaning of a word. For example:

<day> - /deɪ/ <they> - /ðeɪ/

These words differ in only one sound. You can't put a d sound in the place of a ð sound and still have the same word. Words like this, which are only different by one phoneme, are called minimal pairs. You can check whether two sounds are distinct from one another by trying to make one of these minimal pairs. Here's another one, but with vowels:

<pat> - /pæt/ <pet> - /pɛt/

These minimal pairs are examples of phonemically contrastive environments! They differ only by one sound.

This website has a list of minimal pairs for other English sounds (1). It is also possible that you replace one sound with another, but you don't get another word. In that case, you're dealing with allophones (short explanation at the bottom of the post).

It's important, however, to know that not all languages have the same phonemes. I picked these examples for a reason: Dutch does not have the /ð/ sound, nor does it have the /æ/ sound. People with a Dutch accent are very likely to pronounce they and day the same (both with a /d/, which Dutch does have)! They'll also do that with pet and pat (both with an /ɛ/). Even if they can hear the difference (which some people may not), it is still incredibly difficult to actually pronounce it.

Now, to explain the joke:

Until they're about a year old, babies can tell apart a lot of sounds. To actually learn the words of their language, though, they have to know which sounds are contrastive (i.e., phonemes), and which are not. Which ones change one word into another, and which ones are just a font change (allophones are more complicated but shush). The more phonemes a language has, the more contrastive environments a language-learning baby is exposed to. All the sounds that are not contrastive in their language get put on the backburner and go kind of ignored.

This skill of being able to tell many sounds apart is one that lessens as babies age, presumably so they can focus on more important parts, like all the phonological rules of their language(s). But this means that it will be harder to tell apart all those sounds that get put on the backburner. That's the experience the OP of the joke describes: the consonants they mention are strange sounds to them, they weren't provided with the tools (contrastive environments) to learn to tell them apart when they were really young (infancy), so they can't tell them apart now.

Criminally short explanation of allophones: allophones are the different ways in which you can pronounce a phoneme. Not all phonemes in a language have more than one, but they all have at least one (aka, they all have at least one way to be pronounced). If anyone wants me to go more in-depth on that, shoot me an ask and I'll make a separate post for that.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Can we ask multiple questions in one ask?

Oof, good question. Generally, I'd prefer to keep answers separate so it's easier for people to find the answer to their question from the masterlist, and so posts don't become really long. However, if your questions are highly related, it may be better to ask them at the same time. If I think it's better to answer them separately, I'll just link the answer to the other question(s) in each post.

If you're not sure, just put them in one ask, and I'll see what works best.

#housekeeping#I considered at first to make a point for this in the guidelines#but I felt making a hard rule of it would make it too complicated

0 notes

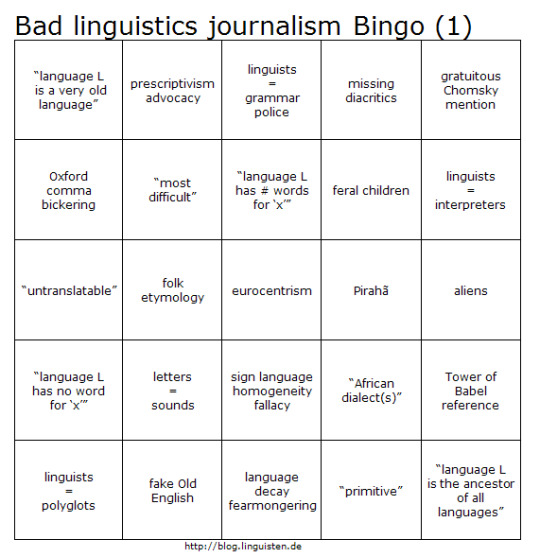

Photo

Bad linguistics journalism bingo

Do you feel like crying every time you read, see or hear anything concerning linguistics & languages in popular media? Does the n-th installment of the Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax™ make you cringe? Are you tired of writing letters to editors correcting them about ling & lang facts? Then this is the game for you.

If you have suggestions for further sheets, please contact us.

[image edited / replaced]

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

I wanted to add on to OP by focusing on the "sound" part of your question. Gonna preface that this is probably the "if you really want to nerd out about it" option, but I love phonetics and phonology, and writing, and couldn't resist.

One thing you can play around with when creating new words is the phonological rules. I assume from your question you're writing in an existing language and want the new words you're using to fit within that, so essentially what you'd do is look at the sounds of that language and find the patterns (I would love to make a post on the rules in English sometime but alas I do not have the time tonight), so that your words sound like they've always been part of it. English words, for example, cannot start with "/vs/" (by that I mean the sounds /v/ and /s/). There can potentially be loan words that do, which would be exceptions to the rule, I guess. But in general, they don't. So you'd know to avoid that sound sequence in your words.

Secondly, you can combine the above with affixes. "What's he looking so hudgly for?" doesn't sound as off when part of the word is already familiar to the reader. They can tell (granted, from more than just the affix) that "hudgly" is an adverb.

Thirdly, you can use sound symbolism! In English and a bunch of other languages, for example, swear words rarely contain the sounds /w/, /r/ (I mean the English R, I don't have an IPA keyboard atm), /y/, or /l/. In fact, when people change a swear word to make it less rude, they put one of these sounds in there quite often, think of the words frick or darn for example. The paper (the sound of swearing, by Lev-Ari and McKay, 2023) cites some fun other kinds of sound symbolism as well.

Then, though this is more of a "just avoid this one thing" and also not about physical sound (I'd argue it's more of a "visual" sound thing) rather than a "here's a linguistic tip", is to stick to the same spelling rules the language you're adding these words to uses. The words won't stand out as much that way. It's more of a personal opinion of mine rather than like, proper advice, but I'd argue that if you want your words to blend in, you need to make your spelling a bit boring (unless for a particular word it makes sense not to, then spelling is a great way to make it stand out, if you use it right).

Finally, in the same vein as making the words internally consistent with the setting like OP said, it also helps if you can make context do the heavy lifting when explaining what the words mean, especially if there are words you plan on using more often (not all words need their exact or even vague meaning explained, of course. in fact it's perfectly possible your characters might not even know the origin of the swear word they're using, speaking of personal experience). Take the word "hudgly" for example.

You already know it's an adverb, and it was combined with the word "looking" earlier, so it suggests that "hudgly" says something about someone's appearance. You can use the body language of your characters to indicate whether this has a negative or positive meaning, and descriptions to further illustrate what it describes (maybe your character has magic markings which are fading, or is an alien who has a physical feature humans don't have, that can change with emotion, for example).

alright so i know that this isn't what you normally get asked but... do you have any tips on making fictional slang terms and names sound normal? im writing a dystopian novel and every time I make up a name or slang i think ‘hey! that sounds fucking stupid!’

this is going to be very vibes-based, and definitely more "writing advice" than "linguistics," but hey i'm a writer sometimes and i read a lot of sci-fantasy.

i think it's less about making them feel "normal" to a real-world audience and more about making them feel "lived-in" within your universe, kind of like making costumes believable by treating them like they're just your clothes. there's only so far this can be successful when you're introducing invented terms because they'll still get tagged as being out of step with a naturally acquired lexicon, but if they're internally consistent for the setting, that goes a long way. be aware of what these things mean to your characters and, for your own reference, what their real-world approximations might be.

linguistically, think about the comparisons to those words in the real world: where do they come from, and how did they reach their current forms? like this post from last week about the transformations of originally heretical exclamations.

#I think this one does actually fall under off-topic to some degree lol but I couldn't resist I love worldbuilding like this#reblogs#writing advice#I'm not gonna tag it with the areas of linguistics this touches#I don't think I went all too far in depth for that

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

listening to the pronunciation samples wikipedia offers of different types of consonants and you know what, I don't believe some of these are actually different sounds. I think this is some audiophile shit like gold-plated cables.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

When do you use de and het in Dutch? (articles)

As said in the tags of the person above, there are a bunch of affixes and word groups you can memorize for this! It won’t cover everything, but it’ll cover most, barring a few exceptions. Also don’t worry, learning the Dutch articles is tough even for Dutch kids.

Below there’s a few lists of things you can keep in mind when learning. Source (page in Dutch): onzetaal.nl

Words that use both

First, since I’ll put a cut under de because one of the lists gets quite long, I’ll note that some words can use both het and de, but their meaning may change depending on which one. If you want, I’ll make a separate post on that since it’s quite interesting to look into, but it would get quite long here if I were to list them all. This website (Algemende Nederlandse Spraakkunst) discusses it, but unfortunately, I couldn’t find a source in English on my home laptop (aka without access to all the fancy schmancy university libraries and databases) that specifically discussed the logic behind the words that use both.

Het

Het is the neuter article in Dutch, though, since I noticed you're a German speaker, that does not mean any word that uses das in German uses het in Dutch (I'm learning German myself and learned this the hard way...)

All diminutives, even if their regular form uses de, use het. Diminutives in Dutch typically end in variations on the suffix -je.

Countries and other types of places (provinces, cities, towns, like that) use het, if they aren’t plural: het kleine Nederland (the small Netherlands), het mooie Gelderland (the beautiful Gelderland).

Then a few quick categories: metals, sports and games, languages, the wind directions (e.g., het noorden, but also combined forms like het noordoosten), and names for goods, like silver, wood, and bread (zilver, hout and brood).

Words with two syllables that start with be-, ge-, ver- or ont- all get het as well.

The same goes for words that end in: -isme, -ment, -sel and -um, though there are some exceptions to this rule like “deksel” (lid), which can take both het and de, and “datum” (date), which uses de. I couldn’t find an exhaustive list of exceptions, unfortunately, but I think you’ll come quite far once you’ve mastered the basics either way.

De

All plural forms (including of the categories above) get de.

Then there are some general groups, but again, there will be exceptions to most of these: fruits, trees, and plants, rivers and mountains, numbers and letters, and most words which refer to people, regardless of gender, so de vrouw and de man (the woman, the man).

Then words that end in one of these suffixes generally get de, but there’s quite a lot, so I’m putting a cut here. There are exceptions within most of these categories, though. I hoped this explanation helped you a bit!

-heid

-nis

-de

-te

-ij

-erij

-arij

-enij

-ernij

-ing

-st (when it follows the stem of a verb)

-ie

-tie

-sie

-logie

-sofie

-agogie

-iek

-ica

-theek

-teit

-iteit

-tuur

-suur

-ade

-ide

-ode

-ude

-ine

-se

-age

-sis

-tis

-xis

*shaking the dutch language by the neck* when het instead of de??? tell me!!!

#reblogs#dutch grammar#language learning help#quick note for housekeeping is that Dutch is my native language so for Dutch specifically (and I guess English given my studies)#I can get into topics like this#dutch articles#dutch

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is a word? What is a sentence? And why is the answer "we aren't quite sure"?

This is my first time answering an ask, I'm still streamlining my process. I don't expect each answer to be as long as this one.

Also have a question about something language-related? Check out my ask guidelines here.

I’ll answer your first two questions separately, and then base my answer to the third one on that.

Obligatory disclaimer I put above every post: I am a student undertaking this blog as a hobby. If I am not familiar with the topic at hand, I will do my best to read up to provide the best possible answer, but I may not always have time to go into depth, meaning some answers will be more detailed than others. I also try to keep things as simple as possible, so I may not always go in-depth on theoretical debates, especially not within fields I am not as specialized or interested in.

TLDR:

Both a word and a sentence can be defined in different ways depending on research areas and needs for those research areas. Writing conventions govern how words can be told apart in written language, and the phonological (sound) rules of a language aid you in learning how to separate words from each other in spoken language. I would argue that we do know what a word is and what a sentence is, but formulating an exact definition is difficult because certain nuances and different perspectives are simply hard or even practically impossible to squeeze into one definition.

What is a Word?

This is a very broad question, because there are quite a few ways to interpret it. That’s because from your average person’s point of view, a word already has multiple elements. To name a few: its appearance in writing, pronunciation, and meaning.

As a result, you can come up with the following questions (not an exhaustive list for the sake of oh my god 1.5K words…):

How do we define a word?

How can we tell words apart in writing?

How can we tell words apart in speech?

How do we define a word?

The first of these questions is by far the hardest to answer, and, I assume, the one you meant. I wouldn’t say “we don’t know”, but rather “we can’t agree because each definition serves a different purpose” (we being linguists, though I’m not so sure I can call myself one yet). For example, according to the Cambridge Dictionary of Linguistics, as cited on Wikipedia (my uni library access is messing with me, sorry, I’d have taken the direct quote otherwise) word is “a basic element of language that carries meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.” In other words, it has to mean something, it shouldn’t have to be attached to something else, and you can’t cut it short and still have it function as it would have otherwise.

If you just want a basic understanding of what a word is, then I think personally, that’s a decent place to start. This would be a very long post (and a very long week) if I were to go over the different fields in linguistics and the way they’d need to define a word, and how that all causes linguists to seemingly disagree on what a word is (I would argue that depending on a field, one feature of a word, like its pronunciation, for example, may simply be more useful to focus on. That the sun is yellow-ish is important for a painter to know, but an astronomer may be more concerned with idk, its gravitational… something. I’m sorry I’m neither), so I’m not going to do that here, but if you’re curious, I’d suggest to just go through the Wikipedia page for "word" and click on the cited works in the first section, then read through the arguments given for those definitions.

How can we tell words apart in writing and speech

In writing, in the system I use now, it is quite easy: you can tell apart words because they are separated by punctuation, barring specific cases where words are glued together for stylistic reasons (in which case you would be able to figure out what the separate words are from the context). In programming languages (which are not typically considered something linguists study, I think, since we focus on human language, but it seems like a nice example), different variations using case is often used to set apart words without using spaces or special characters. LikeThisForExample. In your tumblr url, you may use hyphens to set apart words, or let context do the job. On AO3, you can use BothCase and_underscore to set apart words in your username.

In speech, it is a little harder. Scroll to a list of languages, pick one you’ve never heard of, and listen to someone say a sentence in it as if they were having a normal conversation. It likely sounds like a stream of gibberish, while in your own language, or even a language you are not very proficient in, but have some understanding of, you can tell where the word boundaries are. A simple assumption would be that pauses in speech set apart words, but then you run into the problem above: we don’t actually always put pauses between our words, especially when speaking to someone we know can understand us.

So how do we know then? Simply put, we are aware of the rules around the sounds in our native language. Before we’re even a year old, barring hearing or cognitive issues, we start being able to tell what sounds are part of our language and how. What sounds precisely we learn to listen to, depends on the language(s) we’re learning (note how often in sci-fi, the conlangs have sounds English doesn’t, it makes them sound more foreign), so the specific things we pay attention to in order to identify chunks, usually whole syllables. A number of other processes and bits of knowledge (first language acquisition is a huge branch I could not possibly cover in a single post, especially given all the things linguists disagree on or have disagreed on there) then help us fit the chunks together (or keep them separate) like a bit of a puzzle, to tell apart words even when there are no pauses between them. There are rules in a language, for example, about what sounds can follow each other in the same word. In English words, “zv” is not a combination of sound that can occur (if you found a word that does have these sounds (not letters) together, then it’s likely borrowed from elsewhere), so, once you’ve realized that’s the case, you’ll know that when you hear a set of chunks word ending with the “zv” combination, there must be a word boundary between those two sounds.

What is a Sentence?

I won’t write as long as a piece of text because a lot of the “disagreements” about the definition of a sentence take place in fields I am not as well-versed in (syntax and I have a complicated relationship called I got good grades but I don’t know how and thus don’t trust myself to write a post on it without doing more extensive research than I allowed myself when starting this blog), and this post is currently twice as long as I intended, but again, different branches of linguistics have different needs for their research, and different viewpoints, and thus define it in different ways.

Though, for sentences, I wouldn’t say it’s as complicated as for words. If you look at it in terms of pure grammar and syntax, you could define it as the largest grammatical “container” in a sense (it then contains one or more clauses, phrases, words, and morphemes). In written language, there are specific written conventions or symbols that mark the beginning and end of a sentence. In this case, a capital letter and a period or question or exclamation mark.

After defining a sentences, you can categorize them too (just like words). An interrogative sentence is a question, for example.

In terms of sound, sentences aren’t as interesting to most linguists because then an utterance (which can be less than, equal to, or more than one sentence, as utterances are separated by pauses the speaker makes) is the central element that is looked at. I imagine looking at sentences wouldn’t be as useful until your research also involves some element of grammar.

“And why is the answer ‘we aren’t quite sure?’”

See, conclusion of the post and this veers into “my personal opinion” territory is that I don’t think the answer is “we aren’t quite sure”. It’s more that it’s difficult to figure out a string of words that precisely defines these two concepts in a way that fulfills the needs of all researchers in the field. You know, intuitively, what a word is. For the sentence that may be the same, although it’s also very possible you had a teacher who gave you a definition at some point. We know what they are, it’s just difficult to put into words effectively.

It’s a bit like colors in that sense. If your language distinguishes between red and blue (I believe the grand majority of languages, if not all, do), and you are able to see both of those colors, then you can tell the difference between red and blue, but if I’d ask you and nine others to draw a precise line (lets be Latin and pretend English doesn’t consider purple a separate color here) to separate red from blue, I’d get a line in ten slightly (or maybe even very) different positions, despite you all knowing when a thing is red, and when a thing is blue. It’s just the exact boundary that gets a little smudgy.

0 notes

Text

To the people who sent asks, I'll get to them as soon as I can! I'm going back to uni for the first time since a health break tomorrow, so I haven't had the time to properly outline each response yet.

0 notes

Text

100K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DAY OF LANGUAGES!!!

This 7th of May, 2024, we use our own language again!

If your language, native or not, is something other than English, on May 7th you can speak that language all day!

You’ll blog in your chosen language(s) all day: text posts, replies, tags (except triggers and organizational tags).

Regardless of what language people choose to speak to you, you can answer in your own.

Non-verbal, non-written languages (like sign language, dialects, otherwise non-written languages) are more than welcome! See my FAQ for tips

English native speakers can participate in any other language they're studying/have studied/know.

The tag is gonna be #Speak Your Language Day or #spyld for short.

Please submit me some language facts for me to share on this day <3

Pinned post and FAQ

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterlist of Answered Questions and Discussed Topics

I will add links to each answer I've given to this post so you see if I have already answered your question. If I've made a post for a topic instead, you'll find a link here too.

I may revise and reorganize this post as the blog grows because the best way to structure it will likely depend on the kind of questions you guys ask me.

What I've talked about already:

Definitions of Linguistic Concepts

"What is a word? What is a sentence? And why is the answer "we aren't quite sure"?" - answered on 15/5/2024

"What is a phonemically contrastive environment?" - answered on 26/5/2024

Dutch Grammar

"When do you use de and het in Dutch? (Articles)" - answered on 16-5-2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome to WhatsLanguage!

The idea of this blog is to introduce people to linguistics by answering questions about language and linguistics. So, this blog is specifically targeted at people who don't have a background in linguistics (everyone is always welcome of course, but just to state the target audience).

My ask box will (as long as I have the time) be open 24/7 for any questions about linguistics and language as long as they meet the following requirements:

1. They are not translation questions (e.g., "how do you say x in y language", or anything equivalent)

2. They haven't been asked before (for very general questions that can be asked in may different ways I might make separate and slightly longer posts instead). If your question has been asked or before, I will redirect you to the masterlist of answered questions and discussed topics.

3. They can be answered at a level people without a background in linguistics can understand while still being relatively concise. I'll still answer the ask, but I have a limited amount of time and expertise, so I may not always be able to go in-depth or cover all the nuances. I'll happily try to point you in the right direction for further research or explanation, though.

4. I cannot give advice on how to pick your BA or Master's. This blog is solely about the topic of linguistics. For advice about studying it, I suggest you look up brochures or open days of colleges and universities in the country you'll be studying in.

5 notes

·

View notes