Hello, welcome to my Japanese language blog. I'm going to use this as a place to help me, and hopefully others, study Japanese without fear of mistakes. (Because I will be making a lot of them I'm sure) 私の日本語のブログへようこそ。一緒に勉強しましょう

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Difference of それに、それでは、それで、それでも

1. それに = on top of that; in addition...

• このレストランは料理が美味しい。それに、値段も安い。

This restaurant serves delicious food. On top of that, the price is cheap too.

---------------------------------------------------

2. それでは = and so ...; and now...

• それでは、次の議題に移りましょう。

And so, let's move on to the next topic.

---------------------------------------------------

3. それで = so; therefore...

• 昨日は大雨が降った。それで、試合は中止になった。

Yesterday it rained so heavily. Therefore, the game was cancelled.

---------------------------------------------------

4. それでも = even though A, but still wanna do B; Despite..., but he still...

• 雨が降っている。それでも、彼は出かけるつもりだ。

It is raining. But he still intends to go out.

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

how it started:

”ohayou gozaimasu - good morning” i see i see

"konbanwa - good evening" ok yea got it

"oyasumi nasai - good night" memorized!

how it's going:

日本語はちょっとだけ話せるけど...

いいえ、全然ペラペラじゃないです。

いやいやいや、本当に何もわからないよ。

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basic adjectives in Japanese

大きい (おおきい) - big

小さい (ちいさい) - small

高い (たかい) - tall/high

低い (ひくい) - short

新しい (あたらしい) - new

古い (ふるい) - old

きれい(な) (きれい)(な) - beautiful/clean

汚い (きたない) - dirty

明るい (あかるい) - bright

暗い (くらい) - dark

簡単(な) (かんたん)(な) - easy

難しい (むずかしい) - dificult

速い (はやい) - fast

遅い (おそい) - slow

おいしい (おいしい) - tasty

352 notes

·

View notes

Text

This might be a very niche take but I think we should take people's reasons for learning a language in mind when suggesting how they go about it

I've seen people in a lot of Japanese learning communities tell other to never watch fantasy anime (or anime at all sometimes) or read anything that's not slice-of-life or actual literature because "people in real life don't speak like that"

And while, yes, that's true, native Japanese speakers do not generally speak like anime characters, uhhhh... The probability of me watching a fantasy anime in the course of a month is significantly higher than the probability of me going to Japan in the next five years. So understanding anime character speech is in fact more relevant to me than, idk, business lingo

And, I don't think that's a bad thing personally? Learning a language because you want to better understand content you find fun is just as good a reason as learning it to live in the country where the language is spoken, and it's fine and reasonable to adjust your learning strategies according to your personal goals

#when people ask why I study Japanese lately ive just been saying 'purely weeb reasons'#and honestly its made the conversation not only funner but also the random advice ppl give me is no longer the same basic random stuff#also someone gifted me hidive?!#The best advice for language learning is genuinely to let go of your embarrassment#learning japanese#advice

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to get good at pronunciation

Some of these you might already do, some not, but I hope it helps a bit!!

Listen to lots of music

And not just listen, read the lyrics (you can also use this opportunity to learn new words) and say them! Sing them, read them out, mutter under your breath on public transport, try to mimic the exact way the singer says it, try to get your mouth accustomed to the way the words are shaped.

Listen to podcasts, if possible

This makes you more accustomed to the sound of the language as it is in an everyday context. In music, people often give words a different rhythm than natural, or slur their speech and omit syllables, so podcasts can help provide you with more "usual" speech too.

Study phonetics

Actually take a book on phonetics and study it, with rules and exceptions and preferably audio example.

Every time you learn a new word, check the pronunciation

This goes especially for languages with inconsistent pronunciation or where the stress changes the word a lot! Listen to the Google/Yandex translate audio of it, or check wiktionary, and try to say it out loud too. Sounds frustrating and pointless but does genuinely help

When you encounter a new word, don't type it into the translator, use voice recognition instead

Say the word until it recognises, check the meaning and the correct pronunciation, and if you were wrong at first, say it a few times out loud again. This helps build your intuition about correct pronunciation

If it's possible, ask the opinion of native speakers

They can give you feedback and point out any consistent mistakes, it helped me more than I expected

Talk as much as you can!

Remember, practice makes perfect

Most importantly, remember that it's okay to have an accent and it sounds really pretty :]

Most native speakers find it pretty if you have an accent in their language! The main goal is just to be understood, your accent doesn't make you bad at the language. Keep up the amazing work 💜

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

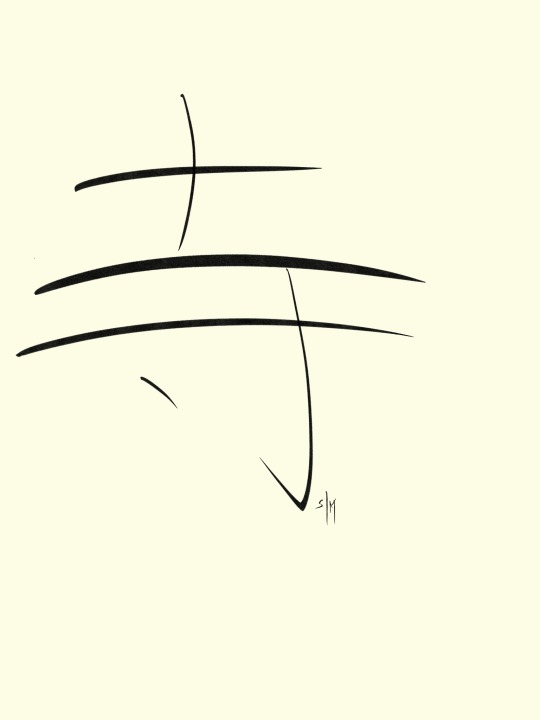

Kanji that use 寺

I am finally making a post about something that has been driving me crazy since I started learning Japanese.

I have seen these words so often in sentences by now and even used some of them myself, but I still confuse them while reading sometimes and I want to be really clear on these when I next appear for JLPT.

The words listed in the image:

侍

侍 - samurai

侍する (じする) - to wait upon, to serve

侍べる (はべる) - to wait upon, to serve

侍史 (じし) - private secretary, also means “respectfully” when added to the name of an addressee

侍女 (じじょ) - ladies maid

侍妾 (じしょう) - concubine, mistress

侍講 (じこう) - tutor to the daimyou, tutor to the emperor or crown prince during the meiji era

————————————————————————

待

待つ (まつ) - to wait

期待 (きたい) - anticipation, expectation, hope

待つ身は長い (matsumihanagai) - a watched pot never boils

招待 (しょうたい) - invitation

乞うご期待 (こうごきたい) - stay tuned

待望 (たいぼう) - waiting expectantly, waiting eagerly, looking forward to

待宵 (まつよい) - night where one waits for someone who is supposed to come

絶待 (ぜつだい) - incomparable, absolutelness, supremacy

————————————————————————-

特

特別 (とくべつ) - special

授受特性 (じゅじゅとくせい) - intent

特異点 (とくいてん) - singularity, special point

特盛 (とくもり) - extra large portion (eg. with rice dishes)

特技 (とくぎ) - special skill

—————————————————————-

持

持つ (もつ) - to hold

間を持つ (まをもつ) - to have a commanding presence

平和維持 (へいわいじ) - peacekeeping

支持率 (しじりつ) - approval rating

気持ち (きもち) - feeling

出前持ち (でまえもち) - food delivery person

持ち物 (もちもの) - one’s property

———————————————————————-

峙

峙つ (そばだつ) - to tower, to rise

対峙 (たいじ) - confrontation, squaring off against

————————————————————————

恃

恃む or 恃 (たのむ) - to request

(Alternative kanji of 頼む)

—————————————————————————

畤

Festival grounds

—————————————————————————

時

時疫 (じえき) - epidemic

時 (とき) - time

��代 (じだい) - era, epoch, period

田沼時代 (たぬまじだい) - Tanuma period (1767 - 1786 CE)

黄昏時 (たそがれどき) - dusk, twilight

時たま (ときたま) - once in a while, occasionally

時の帝 (ときのみかど) - emperor of the time

時好 (じこう) - fashion, fad

時季外れ (じきはずる) - unseasonal, out of season

旧時 (きゅうじ) - ancient times

時計学 (とけいがく) - horology (study of the measurement of time)

安静時 (あんせいじ) - at rest

—————————————————————————

塒

塒 (ねぐら) - roost, hen coop

塒を解く(とぐろをほどく) - to coil in on itself (eg. like a snake)

—————————————————————————-

鰣

鰣 (はす) - a type of freshwater fish

—————————————————————————-

詩

詩人 (しじん) - poet

——————————————————————————

Please feel free to add to the post if you know others!

(I wrote part of this post once and Tumblr didn’t save my progress while saving the draft, for some reason, so it got erased and I had to write it all over again, so pardon me if there are any typos)

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Went to a Yozakura (夜桜) event a few weeks ago, and got to hear them play the Koto (琴).

夜=よる= night

桜= さくら= Sakura (cherry blossom)

夜桜 = よざくら = night time cherry blossom viewing (think hanami, but at night/evening)

The Koto (琴) is a 13 string Japanese zither, aka a Japanese harp.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Took a while, but I did it~

I know it's been 30 years, sry, but I'm back for a bit. I'm finishing up a Japanese culture course at Uni and when it's fully over (I don't want to be accused of plagiarizing some weird Tumblr so I'm waiting lol) I'll post the culture pieces I wrote, and I'll link the ones that have online resources and whatnot. So in like a week and a half to two weeks keep ur eyes peeled 👍

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dissemination of Chinese written language throughout the east.

Roughly 5000 years ago across the world for one reason or another people began to develop the written language. Over the centuries came the rise, and fall of some languages, as well as the continued evolution of others. One such language that not only continued to evolve, but also contributed to the creation, and development of the written languages of other nations, is Chinese.

Several languages across East Asia were influenced by Chinese. The three languages discussed here will be Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. During the third century BC China’s first dynasty came into fruition. It only lasted a few decades though before the next, the Han Dynasty, began. The han dynasty lasted for several centuries during which China began a period if expansion. After China conquered the surrounding areas, and islands, they would ‘recruit’ the locals to learn the language and work for them. They did this as a means to disseminate their language amongst the locals, and to expand and strengthen their authority in those regions. This was the case for both Korea and Vietnam, however Japan was slightly different. It is thought that somewhere around the fourth or fifth century the ones to bring the chinese language to Japan was Korea. By the 7th century Korea, Vietnam, and Japan, while still largely illiterate, had began to adopt the Chinese writing system as their own. They did this by ascribing the meaning of the written character to the verbal pronunciation of their own language. So the same character in Japan or Korea can mean the same thing, but have wholly different pronunciations. That does not mean that the Chinese pronunciation of the words has been completely removed from the language however. In both Japanese and Korean there are multiple different ways to pronounce the characters which can be figured out with conversational context, and surrounding kanji. Over time other such alterations have been made to the written Chinese language to further suit each language. For example in in Japanese the word basket uses the kanji 毛 meaning fur. This does not mean that fur is used anywhere in the basket making process or anything related necessarily, just that a part of the words pronunciation needed to be supplemented with another kanji. This is what’s known as vernacular writing. Korean also follows this practice, however Vietnamese does not. The Chinese writing system was not fully implemented in Vietnam until much later, around the fourteenth or fifteenth century. They adopted the language using entirely different means, such as adding their own symbols to the Chinese characters to create their own ‘new’ written language. So while Japan and Korea adapted phonetically, Vietnam adapted their language semantically.

Then there is disambiguation. Over time languages must continue to evolve to continue to support our needs and support our ever expanding languages. This evolution can happen either on purpose or on accident, but it will happen nonetheless. This is especially necessary in these countries as Chinese is an adopted writing system that was never meant to support the local languages. This is where disambiguation comes into play. Disambiguation is the process by which something is made more clear. In Japan this was done by introducing what’s known as kana. It’s a new writing system, based on the simplification of kanji, to represent sound, rather than meaning. This allows for the elimination of the need for using kanji like fur to represent an extra syllable in a word like basket, and erases some confusion from the reading and writing process. Once again the approach Vietnam took was different. In order to further disambiguate their language they created entirely new characters of their own to convey meaning. Now they primarily use altered roman script, however they did keep the Chinese style of spacing in their new writing system. Korea also began to diverge from the Chinese Writing system In the fifteenth century King Sejong created an entirely new alphabet to replace the Chinese counterpart. It wasn’t implemented immediately as in the 1950’ Chinese characters were still commonly used across Korea, however since then they have been used less and less, and Chinese characters are far more scarce in Korean papers and literature now.

These types of linguistic practices and evolution are seen globally, not just in East Asia. While being different and far apart our languages have similarly evolved, and continue to do so thus bringing us closer. Especially now in the age of technology, and global communication the adoption of foreign words and practices from all corners of the world into our own has become quite common. A part of me cant help but want a peek at what this will mean for the future of our communication global scale in a hundred or even a thousand years.

#chinese#japanese#korean#vietnamese#dissemination of Chinese written language#history of east asia#culture study#sorry these are written in such a boring way#they were for school so there was no fun allowed

0 notes

Text

Shodo

The art of Japanese calligraphy, also known as shodo, is based on the ancient forms of Chinese writing. What is now seen as beautiful script written in various styles on different kinds of paper, seen on restaurant signage, or even typed out on the computer, has descended from ancient carvings set in stone, bone, and secret bamboo letters.

The oldest Chinese script still visible today is and Oracle Bone Script. This script is written on bones and turtle shells that were a part of a Chinese spiritual rite. The bones and animal carcases were first burned and a sacrifice, or offering to God. Then using the bones a diviner, I'm not sure if there's a Chinese word for this, would then read the divination for the coming season or year, and record it. It was recorded by carving into the bones with other bones available from the ceremony. The scripts that we have found and can still access thus far are typically about the fortune of the coming harvest. Over time it became more common to use ink rather than carving bones or stone, and after hundreds of years, and a hop across the ocean pond, we have the calligraphy we know today. Otherwise known as, Shodo.

Shodo is a Japanese word that roughly translates to the way of writing. There are many different styles of writing that developed throughout the eras. All of which date back to the simple Chinese carvings, and led to modern Japanese calligraphy. The oldest one that I personally know about is known as Tensho. Tensho is sealed script writing. It is written with slow sharp gestures that seem to mimic the motions of carving in stone. Following Tensho came the shodo practice known as reisho. This style of writing is more delicate, even in the upright way you're meant to hold the brush. Reisho is also well known for it's many rules. Such as the way you hold your brush, the symmetry of the piece, the even flow of the lines, and possibly most importantly the fact that each piece is only allowed one tail. Meaning that each stroke that makes up a kanji must come to a full and complete stop, and only one may be waved, or flared, at the end. Reisho was also originally a carved script that utilized stone before ink became the more popular practice.

As ink script became more accessible the need, and desire, to send letters arose. When sending letters in China they did not at first use scrolls or any form of paper, but rather bamboo. In order to send private letters they would write their message on the inside of bamboo, close it all up, and seal it with clay before sending it. This way they would know if the letter had been tampered with or opened by anyone before reaching its target audience. This is known as (I cannot read my handwriting, or find any similar words in my search online, sorry. But seriously, what a cool way to send messages.)

After some time though a new era of calligraphy rang in. This time it was sousho, or cursive. This style was, as you'd expect, more flowy and interconnected. However with kanji being as complicated as it is it was hard to interpret the cursive style writing, amongst even those that spoke the same language. Thus, in the 9th century, the modern typeface known as Kaisho was born. This is the font that is used most commonly in Japan. It's found in books, taught in school, and is even the base internet font for kanji and kana. However there are multiple writing styles that fall under the umbrella that is Kaisho. So while they share the same name they can look quite different, and may very well one day evolve into their own era of shodo.

The popularization of ink brush calligraphy did not just travel from China to Japan, but is also popular in Korea, and as I've recently learned is growing in Vietnam, India, Taiwan, and of course here in America. Though from what I gather in comparison to American styled Japanese calligraphy, traditional calligraphy still being exhibited in Japan is somewhat more strict or rigid in its expression. By that I mean Japanese calligraphers are likely not going to take the same liberties with kanji as Americans do such as splatter paint styles, or using more eccentric tools and such. Though maybe that has to do with the fact that in America pursuing calligraphy would be more of a hobby, whereas in Japan shodo is or can be, a profession.

Words of Interest:

Shodo- way of writing

Oracle bones- bones used in a spiritual rite for the sake of divination / Oracle/ fortune telling

Tensho- seal script

Reisho- clerical script

Soshou- cursive script

Kaisho- regular script

Kotobuki- large scroll type or hanging script meant to wish a long happy life

Fude- brush

Sumi- ink

Reiwa- current Japanese imperial era meaning order and harmony

0 notes

Text

Sadou

The way of tea~

A brief description of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Matcha green tea was brought over to Japan from china. From there it was used by the Shogun and samurai and then eventually planted and spread even amongst the common populace. Then eventually internationally, making Japan the green tea capital of the world.

The tea ceremony begins in the zashiki, or the sitting room, with the hostess cleaning the tea ceremony utensils with a combination of a cloth brought for this specific purpose, and some of the boiling water from the kettle. (Typically not an electric kettle, but rather a large cast iron or ceramic brazier and kettle.) This is not done because the dishes are dirty in any way, but rather as a spiritual practice for the sake of purity. Similarly to the way a person would cleanse their hands and mouth at the outdoor basin before entering a temple, shrine, or in some cases an ochaya. A teahouse or tea shop. While the hostess is doing this, and preparing the sweets, the guests are meant to take that time to observe the Tokonoma. The Tokonoma is a small inlet, or section of the room, where a display is placed. The art displayed in the tokonoma primarily consists of a calligraphy scroll, and chabana, a seasonal flower arrangement setup for the tea ceremony. The two pieces are meant to reflect a similar theme related to the ceremony. One such example would be the phrase Ichigo ichie, meaning basically that you only experience each experience once or you only live once, so cherish each moment as it passes by.

Once the hostess is done with their preparation, and the guests are done admiring the art, the sweets are passed on to the guest, and the tea portion of the ceremony begins. The sweets served are known as wagashi. There are three types of wagashi that I know of. One is youkan, a sort of gelatinous type sweet made from red bean paste. Higashi, dryer more cookie or powdery type wagashi. Then there is the stuffed mochi type wagashi. All of which come in many unique shapes and styles, typically involve red bean paste, and oftentimes rely on other seasonal flavorings. These are meant to be eaten before consuming the tea. Once done and the time to drink the tea has come, there is a certain level of ceremonial practice that must be followed once the tea is received, but before it can be drunk. The level of which will vary depending on the level of formality of the event, but overall the steps are generally the same. The hostess will pass the tea by placing it on the tatami mat, the guest will receive it, bow to the hostess, and bow to the other nearest guests in attendance. Then the guest will lift the teacup again with their right hand, rotate it a bit, sip the tea periodically until it is finished, and then wipe the place they drank from before bowing once more to the hostess. Then once again the guests should take a moment to reflect on their experience,or observe art that is the ceramic bowl the tea was served in. While there are more accurate answers which may be more correct in how to do this, such as how far you rotate the cup, or the order in which or number of times you bow, I do not personally know the specifics, and from my understanding they do vary based on formality and which institution one learns from. But basically to attend a Japanese tea ceremony all you need is the desire to try, a little bit of patience for us Americans who are typically in a hurry, and respect both for the culture and ceremony taking place.

Some unspoken rules about the tea ceremony are that those guests in attendance should typically not wear overly smelly perfumes or scents. They should not wear clothes that will disturb the ceremony by being overly gaudy or catching on the tatami mat. Going hand and hand with this they should also wear shoes that are easily removable as they cannot be worn on the tatami mat where the ceremony is held. No smoking, and avoid wearing heavy make-up specifically on your mouth so as to avoid getting lipstick all over the cups.

Words of interest (not explained in text):

Sadou: the way of tea. Some places also pronounce it chadou, but sadou is more correct/common.

Chadogu: tea tools

0 notes

Text

Edo Avante Garde

A documentary on the history of Edo period Japanese folding screens.

Before discussing the documentary I would like to give a brief introduction to its creator. Linda Hoaglund is a film producer, and translator that graduated from Yale, and was born and raised in a more rural part of Japan, by her parents who went there as missionaries. As such she was in just about every way except genetically Japanese, and had grown up living a very Japanese way of life. Thanks to this she is fluent in Japanese. Her knowledge of both Japanese and Western customs and cultures aided in her efforts to receive help/cooperation from many temples, shrines, and art institutions to create this documentary.

In the 1600’s, at the start of the Edo period Tokugawa Shogun took power leading to a peaceful era post civil war, raising the status of samurai, and closed Japan off from the West. As such,for the next roughly 250 years, during this era while Japan was cut off from the rest of the world, its economy, culture and art began to flourish.

The art primarily discussed here will be byobu. A Japanese folding partition that is painted with ink, and often decorated with gold leaf paper. The byobu are large roughly 6 foot tall privacy screens that often decorated the rooms of Shogun, samurai, and merchants.

The Japanese painting style is very different from that of the West. Rather than using oils, or charcoal to illustrate a page, in Japan they used ink. The Japanese painting style also does not rely on a focal point to illustrate depth, but rather a layering of things in the foreground, and moving those things in the background further up the page.

Near the end of the Edo era there was also a shift in the power dynamic of the country. From the authorities and samurai over to the merchants where the meaning behind the art being displayed changed. No longer were these large paintings meant to be displays of force and power, but were rather to show a merchant's discernment and wealth. So the mood that needed to be illustrated was no longer an oppressive one represented by large animals like peacocks and tigers, but could change depending on the mood the merchant wanted to give in the room it would be displayed. This gave artists a great deal more freedom with their work. (Using the word oppressive may have seemed strange as a way to describe this type of Art, but not only considering the size, and content, but also the way this media is consumed can make it so. Not only are these paintings quite large, but typically when one viewed them they would not be walking by in the gallery, but rather sitting near them, thus giving the sense of being surrounded.) Because of this Japan entered into an era of experimentation you could say with their art. A combination of hyperrealism and abstract allowing the eye to see an ever-changing scenery on the byoubu. The blank page, or empty space filled with gold leaf, would often be used to illustrate the clouds, the ground, or even just the entire background scenery. This is because as the merchants no longer wanted to overwhelm individuals with the art, the freedom the artists were given led them to making smaller pieces on the byobu. That is not to say however that the pieces are worse or not of equal value to those before, many of them may even be more valuable just because of the level of detail, experimentation, and thought put into the composition. As in these types of painting each stroke counts. It's not like with oils where you can go over and hide your mistakes, but if a mistake is made it is one that has to either be worked with in a way so that it's not noticeable, or restarted. Many of these practices are ones that would not come to the Western world of art until much later. It is this almost modern multimedia, freeform, and experimental aspects that led Linda Hoaglund to saying these pieces were Edo Avant Garde.

Japanese art is heavily connected to nature, religion, and spiritualism. In Shintoism it is believed that every living thing has a spirit. This is reflected in the art of Edo Japan with the practice of Shasei, or drawing from life. While of course many artists approach this in different ways, whether they approach the image with hyperrealism or abstract simplicity, in each painting a sort of character or essence for the animals illustrated can be seen. This is almost directly oppositional to the West where our approach to painting animals is typically very anatomical, and is meant to look accurate to the eye, but is also seen as kitsch or embarrassing. Yet in Japan some of the most famous artists of their time like Ito Jakchu, and Maruyama Okyo, are known to have painted not just any animals, but their own pets. In the case of Jakchu, part of what led him to become so well known was the hyper realistic nature of the birds, and specifically his chickens, that he was painting. For Okyo, they were known for painting a variety of different things, many of them from life, but the ones I can't help but remember the most are the ones they did of puppies.

Now with Japanese art, as I stated before, it's not typically necessary for something to be painted as you would see it with the eye. So long as it is representational of the spirit then often that successful completion of a piece. In the documentary another reason stated for this is the fact that humans are perhaps not meant to be the ones whose point of view is represented by the artist, but rather in many cases it is the point of view of the gods. There are a number of illustrations on these byobu that represents a story, but rather than choosing one specific scene from this story it shows the scene in its entirety, oftentimes the point of view of the clouds. Many of these paintings also depict natural phenomena as works of the gods. Rarely in any of these paintings though is the primary focus a person. Portraits, while very popular in the West, in Japan were rarely done. Even in many of the paintings including people the people are just a small part of it, like the rest of the animals and things in this world. That is yet another reason that many say Japanese paintings are meant to represent the view of the gods.

These are the pieces that inspired the greats such as Hokusai, and directly led to the expansion of Japanese art and culture in the West to shape the works of Van Gogh and Jean Claude Monet

Words of interest:

Byoubu- folding partitions often golden or painted

Shasei- painting from nature

Tarashikomi - wet on wet painting technique

Sensu- folding fans with story or art printed

Avant Garde- new experimental ideas in art

Some thoughts on art:

I had a moment to talk to the filmmaker of the doc. Edo Avant Garde which was shown at PSU, and a lot of what we talked about was how when these byobu are commonly used theyre just opened up in a museum behind some glass and everyone’s walking by, the viewer doesn’t even really get to appreciate just how big the piece is, or get close enough to see the detail, and even the height at which your seeing it is not how it was intended to be viewed. This really ended up taking a lot of the impact, and functionality from the art. Originally the 6ft tall folding screens were meant to fill the room (as a backdrop) of a meeting/ gathering of some sort. They are meant to be seen from relatively close-up, most of the time theyre seen would be from a sitting position making them appear even larger, and with natural or candlelight (which makes the gold leaf reflect differently and is super cool) I think the way that we in the west consume art doesn’t necessarily make sense for those cultures for which their art is not just meant to be a painting on canvas but is meant to be functional, or used/ viewed in certain ways.

For more info:

edoavantgarde.com

#hopefully this makes sense I had to splice together some parts of the essay to make things shorter#sorry it took so long I'm a professional procrastinator~#byobu#japanese art history#Japanese art#japanese study#language and culture study#ty to my friend Lily that took this great pic when we wen to japan#this folding screen is at Ruykoku Daigaku's Oomiya Campus in kyoto#idk who took the second pic but its the same byoubu

0 notes

Photo

「梅・桜・桃」の違い、わかりますか?

どれもバラ目バラ科サクラ属の植物なので、似ているのも当然です。種類によっては例外もありますが、見分けるポイントは花の付き方と花びらの形、そして咲く時期です。

__

Differences between:

Ume / 梅 / plum blossom

Sakura / 桜 / cherry blossom

Momo / 桃 / peach blossom

These Rosaceae family of flowers are all culturally cherished throughout history of Japan, symbolising the beginning of new year and spring. Yet they are often confused!

Here are some tips: plum blossoms as early as January with round petals; cherry blossoms March to April and have a small split at the end of each petal; peach blossoms in April and have pointy petals.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I know it's been 30 years, sry, but I'm back for a bit. I'm finishing up a Japanese culture course at Uni and when it's fully over (I don't want to be accused of plagiarizing some weird Tumblr so I'm waiting lol) I'll post the culture pieces I wrote, and I'll link the ones that have online resources and whatnot. So in like a week and a half to two weeks keep ur eyes peeled 👍

#Japanese culture#japanese calligraphy#Japanese tea ceremony#Chado#Edo art#Japanese art#Japanese language#Evolution#history#?#Do people even still use tags?

5 notes

·

View notes