Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Uncontrollable Women

Wow, I can’t believe this is my last blog post for this class! In reflecting on how much I have learnt about the socio-political importance of visual culture - and in this blog post, I’m going to explore just that - this time, inspired by a video essay by Rooney Elmi. They are the founding editor of Svlly(wood) magazine, a print and digital publication that produces experimental, alternative texts in film criticism, commonly from marginalised voices. The essay is entitled ‘Black Femininity as the Monstrousness: Exploring race, gender, sexuality and diasporic culture in blaxploitation horror’ and analyses Barbara Creed’s ‘7 Deadly Sins’ of feminine character portrayals in the horror genre.

Here are some key takeaways from Elmi’s analysis that will underlie my blog post today:

The Blaxploitation genre is written by and stars black people, and is connected to the post-civil rights era, and Black pride movements in the early 1970s

By embracing the racialised Black monster and turning him into an agent of black pride and power, the blaxploitation films created sympathetic monsters that helped shift audiences away from the usual black monster stereotype

And instead positioned white society as the maker of black monsters

Therefore, Blaxploitation cinema humanised the heavily demonised identity of blackness and repurposed cinema as an artistic venue of Black rebellion, instead of its historic purpose as a tool of white supremacy.

So that I don’t spend this blog post just relaying everything that was mentioned, here’s a link to the video essay: https://www.graveyardshiftsisters.com/archive//2017/05/horror-blackademics-rooney-elmis-black.html

But for all of Blaxploitation cinema’s strengths, it also fails in its portrayal of gender and sexuality, or to acknowledge womanhood and sensuality as equally important strides in the Black liberation movement.

As we’ve established in previous blog posts, what creates the horror in films is often not the supernatural elements, but the very real and brutal aspects of human life that are tied into the film’s premise, such as family secrets in ‘Eve’s Bayou’, violence against Black people in ‘Candyman’, pedophillic predatory crimes in ‘The Lake’.... I could go on. And what becomes clear through Elmi’s analysis is that the ‘horror’ of female characters in the Blaxploitation genre is that fact that women cannot be controlled and categorised.

Alright, hear me out here: when a female character is possessed by a demon, se is often still pure and beautiful on the outside, with a terrible evil lying within, that enacts trouble and terror through overt sexuality. Therefore the horror emerges from the fact that a woman has broken away from a ‘proper’ feminine role, and can no longer be someone's wife, daughter, mother etc - and she is powerful and uncontrollable - terrifying! With a female vampire, she is also uncategorizable - she crosses and hovers on the boundary between the human and the animal, and the living and the dead, and is all-powerful and independent. And instead of celebrating and humanising these aspects of strong femininity in the Blaxploitation genre, it is villainised and portrayed as deplorable.

So moving forward, I am going to embrace those moments of feeling powerful, free from other’s control, feeling comfortable in my sensuality and not pressure myself to neatly fit into a category that society is comfortable with. And I would encourage you to do the same!

So long,

Vedika

0 notes

Text

Hate and Humanity in Victor LaValle’s ‘The Destroyer’

“I don’t owe this country a damn thing except the same hate it’s always given me”

Isn’t it scary how humans can hate just as deeply as we can love? How we can experience our lives so personally while also having the capacity to completely dehumanize the lives around us? LaValle explores these thought-provoking fallacies in his graphic novel, ‘The Destroyer’.

The central themes of artificial intelligence (AI), mortality-challenging medical technology and the power of interpersonal relationships are a vehicle through which LaValle unleashes a wider socio-political discourse on racism in America today. Who is the real monster? Does monstrosity and humanity come from the same place?

Approaching the climactic ending of the novel, Dr Baker asks “It’s not just about how humans treat artificial life, but how you all will treat us. What kind of ethics should we expect? What kind do we deserve?”. This raises important questions about which lives are valued in society, and poses the mistreatment of AI as an allegory for the appropriation and exploitation of Black bodies. The most recent and global wave in the Black Lives Matter Movement washed over the planet in 2020, when the murder of innocent Black people at the hands of police brutality was broadcast across the world. Although many messages emerging from these events were not new information for Black communities, for many more privileged groups, it was the first time they were forced to realise just how little the lives of Black, indigenous and other marginalised people were valued.

“Look at the backflips people will do to find the humanity in that monster… but when they saw a boy like mine, they had no love to spare”.

Ultimately, society is racially segregated and hypocritical. Leaders say we are all equal in the eyes of the law but the enactment of this leaves much to be desired in real life. Young Black boys are shot in the street for obscure and unfounded concerns, such as Akai, the son of mad scientist Dr Baker, who resurrected him using nano-technology. And despite being made out of more nanobot fibres than flesh, her son displays more compassion, patience and humanity than anyone else in the novel.

‘The Destroyer’ is also a fantastic portrayal of Black female rage in a way that is fleshed out properly with her villain origin story. What lies behind her bloodthirsty and unrelenting need for retribution are the lengths that black mothers will go to in order to protect their children – which is also the underpinning theme of Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’. There are supernatural aspects to both of these stories, which serves to alleviate the intense pain that the audiences would have had to witness and what Black mothers have to contend with when a person they love is ripped out of their life in this way. I cannot even begin to imagine what that must be like, and it breaks my heart to even acknowledge that such atrocities are not confined to the pages of a graphic novel.

Lots to think about this week…

Until next time!

Vedika

0 notes

Text

‘Eve’s Bayou’, written and directed by Kasi Lemmons, released 1997

Welcome back!

“Every element of the film -- from the turbulent, stormy performances to the rich cinematography (which includes black-and-white computer-enhanced dream sequences) to the setting itself, in which the thick layers of hanging moss over muddy water seem to drip with sexual intrigue and secrecy -- merges to create an atmosphere of extraordinary erotic tension and anxiety.” – by Steven Holden, from https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/film/110797bayou-film-review.html

This film might just be one of the most challenging, beautiful, inspiring, horrifying, thought-provoking pieces of art I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing. There are so many striking and truly wonderful aspects of Lemmon’s work at play here, and I can’t wait to dive into it in this week’s blog post.

“Life is filled with goodbyes, Eve, a million goodbyes. and it hurts every time. sometimes i feel like I’ve lost so much I have to find new things to lose. all I know is that there must be a divine point to it all, just over my head. that when we die, it will all come clear and we’ll say ‘so that was the damn point’. and sometimes i think there’s no point at all, and that’s the point. all I know is that most people’s lives are a great disappointment to them, and no one leaves this earth without feeling terrible pain. and if there is no divine explanation at the end of it all then well, that’s sad.” - Mozelle Batiste Delacroix

From the very beginning, I felt like I was experiencing true 3D cinema. No, not because I was wearing blue and red paper glasses, but because every character was complex and developed, with a vibrant personality and bringing forward important themes that were central to the film.

Never before have I seen such a diverse range of beautiful Black women in one screen, with different skin tones, hair colours and styles, with different opinions and motivations, and a life outside of their tokenistic affiliation to a man or a white main character. Theres a dangerous sensuality that underscores every interaction in this film, a kind that reminds me of when I watched Tennessee Williams’ ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ as a teenager – the raw and unfiltered sexual nature of each character (apart from Eve and her little brother) and each encounter is simultaneously staring you in the face and nowhere to be seen.

Eve’s Bayou is about trauma, desire, the messy intricacies of family dynamics and at the heart of it all, the perspectives (or ‘sight) of a little Black girl, Eve. From the opening scene and narrative, it is clear that we are viewing the events of the summer through her eyes, both in her youth and reflecting as a grown woman. Memory, sight, contrasting narratives, uncertainty and what we understand from the input of certain information at a young age is a theme woven into the fabric of this film throughout.

‘It plunges us into the interior life of a young Black girl, asserting, with neither justification nor apology, that such a perspective belongs at the centre of the frame, that it should demand our attention.’ – ‘Kara Keeling’ from https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7971-eves-bayou-the-gift-of-sight#:~:text=Narratively%2C%20Eve's%20Bayou%20addresses%20particularly,specter%20of%20incest%20among%20them

Keeling brings our attention to how the patriarchal order and orthodox, logical diagnosis to treatment pipeline is represented by the activities of the father, Louis Batiste. However, he poisons and takes advantage of his position as the town’s doctor, appearing to engage in casual sexual activity with his patients, even when his daughter Eve is with him. In contrast, Mozelle’s ‘gift of sight’ is intertwined with the effeminate care of her clients in a less traditional sense. Which ways of knowing presented in this film is more valid?

I simply cannot put it better than this writer:

‘Lemmons was advancing a critique of the patriarchal order, by valorizing the experiences, the ways of knowing, and the desires of Black women and girls, and that she was doing so without creating any villains. Her narrative poses questions that still resonate today, about gender and gender roles, bourgeois family norms, sexuality, sexual violence, and memory—and its form offers responses to those questions.’ – Keeling.

A woman’s intuition and gut feeling about matters can often be dismissed as hysterical, illogical and crazy. And yet we see the gravity each perspective holds for each of the characters. I found it particularly heart-breaking when Cisley says ‘I believed you then’ when Eve brings up her father’s infidelity for the second time. The older sister was just trying to protect eve from her father’s mistakes by retelling her trauma in a more digestible way – did this do more harm than good?

Cisley is unsure exactly what happened that fateful night where her father struck her, and Eve isn’t able to quite make it out either, but immediately believes her sister’s pain and vows to kill her father for hurting Cisley. But even Eve doesn’t fully understand what she has committed to, and is taken advantage of by the white-faced voodoo woman at the market, who takes her money and provides no comfort to the angry and emotional 10 year old girl.

And I’m sure we can all relate to the sinister nature of gaslighting, or having our experiences and viewpoints interrogated, doubted and disregarded. Of questioning ourselves, of mis-remembering, of trauma and PTSD overwriting what we know to be true, or what we regard to be a threat. I certainly look back on moments where I witnessed or personally encountered racial slurs and discrimination as a child, but wasn’t able to fully realise why something incomprehensible felt so wrong.

What is real? What is recognisable? For example, from the outside, the main family in Eve’s Bayou appear completely perfect: a beautiful, nurturing wife; a successful and charismatic husband; 3 doting and intelligent children; a stunning plot of land for their lavish home. But as we the audience enter the family space with the main camera, we start to see small cracks in the image. Of course, no family is perfect, but the actors provide insight into painfully relatable tension and conflict between different members of the household. We see infidelity and parenting disagreements between the central married couple, we see suspicion from Eve and rebellion from the oldest daughter, Cisley.

The grandmother scolds the parents for allowing the children to talk back and be so involved in family matters, and the aunt ‘Mozelle’ is living as a ‘barren’ woman who has been widowed 3 times but still displays immense strength and plays an invaluable role in the film. The father, played by Samuel L. Jackson, does really love his kids, and they clearly adore him – and yet, through a somewhat intangible patriarchal toxicity, he completely shatters his daughter’s innocence in one selfish, careless night. Nothing is black and white in this film (ha ha), it’s all so complex and messy and I absolutely love it.

I think maybe what I love the most is how we see trauma manifested in so many different ways, but not through racism. Although the family’s land is linked to the life of an enslaved woman, the present-day story is not told through a white lens or focussed around the Black struggle.

These Black characters appear to exist in a community that is not dictated by post-slavery struggles – they are allowed to exist as human beings, not just ‘survivors’. Personally, this was potentially the most refreshing and empowering aspect of Lemmon’s work here: how often do people of colour get to see a Hollywood film that doesn’t reduce their brothers and sisters to stereotypes and ‘lessons’?

Teresa Xie puts words to this feeling better than I can:

‘From the first scene onward in Eve's Bayou, we see a different narrative, one of personal and ancillary experience without the omnipresent feeling of the white gaze. Eve interacts with her family and the outside world without the trauma of racism. However, that does not mean that trauma isn’t explored throughout the film’ ‘Eve’s Bayou is a beautiful exploration of Black girlhood, family trauma, and the confusion of youth. It weaves a tale that fully shows the complexity of Black American life without the white gaze.’

If you are interested, I would highly recommend checking out her article! It helped me to frame and contextualise my thoughts and feelings about ‘Eve’s Bayou’

0 notes

Text

Processing Trauma with Candyman (2020)

Candyman

Candyman

Candyman

Candyman

…. Candyman!

Jordan Peele is back! This time, working alongside director Nia DaCosta to make us question more horrifying fundamentals of the human condition: injustice, trauma, revenge and the legacies we leave behind. As Peele points out, Black horror seeks to represent this eternal dance between monster and victim – and this monster never goes away, it elusively changes shape and form over time. In this context, Candyman represents a painful and unrelenting history of intergenerational Black trauma – from stories of brothers and sisters being lynched, tortured, murdered and exploited for hundreds of years.

I found it particularly striking how many people on the Candyman social impact discussion panel were mental health specialists, highlighting how Black horror films are rarely just a film, but actually a metaphor for a wider socio-political discourse. Dr Ashley defines racial trauma as the psychological and emotional injury that stems from racial bias, discrimination and violence, such as police brutality, microaggressions and denial of opportunities. There’s really no ‘cure’ for this, and often people will find themselves feeling isolated and invalidated, unable to put words to their collective pain and frustration. So, turning to films created through a Black and Brown lens, that center and empower Black characters helps people to feel heard and seen.

In this roundtable discussion, Professor Due points out that despite the gore and bloodshed that many would associate with horror films, the silhouette puppetry employed by Candyman’s creative team creates an emotional distance to express and acknowledge trauma - without audiences being retraumatized by having to witness more Black people be slaughtered or imprisoned on screen. Films that have been directed and produced through a white lens have been known to perpetuate harmful stereotypes regarding ‘aggressive’ and ‘predatory’ Black masculinity, with little to no appreciation of how we got here – what about the systemic violence enacted by white institutions?

‘Candyman’ is also wrapped up in themes of gentrification and urban monstrosity, which can be viewed as a recolonization of space where communities were uprooted, dispossessed and exploited to make way for capitalist interests and white communities. When communities of colour are trapped and redlined into public housing, crumbling from government neglect and geographic isolation, then does Black and Brownness become synonymous with monstrous, dangerous urban spaces?

The 1992 release of Candyman emulates many of the problematic tropes that Hollywood perpetuates, such as the violent and obsessive pursuit of a beautiful, innocent white woman by a scary Black man. This really makes me think about the iconography of the blonde, blue eyed, pure, feminine and untouchable white victim that appears in many films as a stark contrast to the grotesque, unsettling villain with darker skin and dark features. I’m thinking about the subtle xenophobic undertones in the films I grew up with: Scar and his hyenas in ‘The Lion King’ (1994), Ursula and her eels in ‘The Little Mermaid’ (1989), Captain Hook and his pirate crew in Peter Pan (1953).

And finally, what about the years of enslavement and exploitation? Would Hollywood ever release a film where a previously enslaved Black person returns from beyond the grave to carry out revenge on his oppressors descendants? This was another question posed in the social impact reflection for Candyman (2020) and it really got me thinking about the power and influence that visual media has on our societal relations and racialized perceptions of different people in this world.

I’ve thrown a lot of food for thought your way, and I would love to hear your thoughts!

Until next time,

Vedika

0 notes

Text

Class and Privilege in Jordan Peele’s ‘US’

Honestly, when I first watched this movie, I didn't get it. Like at all. Buuut after uncovering the many many layers of its symbolism in class, I struggled to pick what I should even talk about in this post. After taking the time to really listen to each character’s words, and reflect on a lot of the directing decisions evident in how the Wilson family interact with the ‘tethered’, I found that the discourse surrounding class and privilege was staggeringly obvious, and I just didn’t see it right in front of me. Which, I suppose, is true for a lot of people that are lucky enough to lead very privileged lives outside of the cinema - and honestly, is personally a bit embarrassing for me that I didn’t realise this movie motif sooner.

A key theme that almost went completely over my head in the first viewing of ‘US’ was privilege, which is illustrated by Winston Duke’s character ‘Gabe’ trying to make sure the family ‘keeps up’ with the typical suburban middle class lifestyle that is often associated with the domestic ‘American Dream’. For example, taking a beach holiday in Santa Cruz, buying a boat and staying in a neighbourhood that is predominantly made up of white people (or as far as the film shows us).

Zora and her mother look and appear to feel a little out of place on the beach; Zora doesn’t want to go into the water (maybe because she doesn’t want to get her hair wet, but its never specified), which the twins find weird, and Adelaide doesn’t want to relax and tan and drink on the deckchair in the same way that the white mother does - which makes the whole scene quite uncomfortable to watch - so I could really empathise with that uncomfortable feeling of being just a little bit out of place in this white-normative world.

Subtle insinuations that Gabe wants to be on par with his ‘peers’ (the white family in the film) are made through the dialogue in the beginning scenes of the film. Gabe even comments on how Josh just ‘had to’ get that new car, and repeats ‘it’s not about the size of the boat’ and ‘it’s not a contest’ just often enough to generate that feeling of unease and discomfort among other characters. If there’s anything I’ve learned about Jordan Peele films, it’s that nothing is by accident.

Although this film isn’t explicitly about race in the way that ‘GET OUT’ is, we have to acknowledge that the black family at the centre of this film is probably one of relatively few other black families that share their income level.

Whenever someone is in a position of power, there’s always that underlying question of who they had to overtake to get there - which embodies the dichotomy of the ‘American Dream’, which is built on the notion that anyone can ‘make it’ in the United States with sincere, hard work - which is not the case, if institutional racism has anything to do with it.

The ‘tethered’s’ mission is very much based on a ‘dog eat dog’ mindset, and Red even says “it’s our time now”, as the film later cuts to a news channel reporting hundreds of families killed and overtaken by their doppelganger counterparts. When Gabe asks “Who are you people?”, Red responds by saying “We’re Americans” - and that really struck me.

In this film, it feels like Jordan Peele is trying to destabilise and disrupt conventional meanings of what it means to be ‘American’, and actually allude to how American, like many countries, has acquired their wealth through the dispossession, exploitation and oppression of indigenous people, African Americans and other minority groups.

This notion was strengthened by the likening of the tethered outfits to prison jumpsuits in class, a point made by Professor Due, which got me thinking about the horrifying reality of mass incarceration in America, which can almost be seen as a kind of sick, twisted industry that generates free prison labour, profits private prison companies and maintains long standing racial inequalities across the US. OH WAIT - I JUST HAD A REVELATION (obviously probably not the first person to make this connection but whatever) - ‘US’ also stands for ‘United States’ - which makes a lot of sense if I’m running with the idea that this film is really a socio-political discourse on privilege and oppression in modern-day America.

Finally, a little more from me and my personal experiences. Although I don’t like to think about it as much as I should, everything, and I mean EVERYTHING I am and I have today is due to the hard work and sacrifices of my ancestors. From the endless bloodshed and torture my people endured during the fight for Indepedence from British Colonisation in India (which was achieved in 1947 - less than 100 years ago!) to the sleepless nights and workplace discrimination my parents faced as junior doctors that moved to the UK to give their little girl a better quality of life. In fact, I’m going to go call them and tell them how grateful I am right now.

Thank you for reading!

Until next time,

Vedika

0 notes

Text

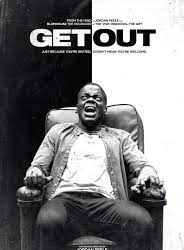

Jordan Peele's 'Get Out'

This course was the reason I chose UCLA as my year abroad university.

(well, one of them). California has many pulls; the sunny weather, vibrant city life and a community rich in diversity - but one of the main reasons that I chose UCLA in particular was their extensive range of exciting, challenging and creative courses in the African American Studies department. Having only taken very serious, historical and, quite frankly, depressing Critical Race Theory classes, I had no idea that engaging with such tough topics like racism, survival and white supremacy could be so…. Funny! Or rather, that we are even allowed to employ humour and laugh together about the ridiculousness of racism when addressing such topics in academic settings.

Since starting this class with Professor Due, my understanding has gone way beyond just humour. I’ve learnt that the horror genre can be healing and that sci-fi stories can open up a world of new possibilities where people of colour can exist apart from the oppressive racial structures that envelop our world today. This class is based around the film ‘Get Out’, directed by Jordan Peele and released in 2017. Among numerous nominations for prestigious awards, Peele became the first African American to win the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

Does everything always have to be about Race?

I was surprised to learn that Jordan Peele didn’t mean for the film to be explicitly about race at the start of his creative process. I feel like people of colour and other minority groups cannot create art without it being completely intertwined with their ‘blackness’ or ‘femininity’ or whatever category great art is shoved into, with little consideration that maybe a piece of work is incredible both because and regardless of its creator’s demographics. Music, film, literature and more are often blocked from competing in the same category as art created by white people - all of the ‘awe’ around a person of colour creating something incredible frustratingly morphs into a snobby tokenism, where people feel like they have to respect and feature it to check a diversity tickbox.

Is this too much of a cynical outlook? As a brown woman with immigrant parents, I have encountered many people that share this twisted sentiment. For example, the head of university applications at my high school told me that I would probably get accepted into a certain university because they ‘need a bit of colour’ - as if my top grades and endless extracurriculars wasn’t enough!

What does ‘The Sunken Place’ mean to you?

For me, I’m in ‘The Sunken Place’ every time I walk into a room and I’m the only person of colour there. Or every time the conversation becomes even slightly political, and I feel completely alone in my outrage at people’s thinly veiled racist comments. Or every time someone comes up to me to tell me that they love curries and had a teacher that ‘spoke Indian too’. I also feel like I’m my sunken place when I go to India and I’m lost in a sea of people that walk, talk and look more Indian than me - when I feel like a fake because I grew up in the UK and have a funny accent and don’t know basic pop culture references that my cousins grew up with.

The sinister coveting and appropriation of Black bodies is a key theme in GET OUT and upon further reflection, I resonated with the commodification and ‘use’ of black and brown bodies too. You wouldn’t believe how many times me and my brown friends have heard that Indian girls are ‘exotic’ and ‘totally my type’. The fetishisation of Asian bodies and culture in the West is disgusting and confusing. I’m in ‘The Sunken Place’ when I feel like people are seeing my colour or womanhood first and are surprised to learn that I, in fact, exist.

For me, ‘The Sunken Place’ is where I go when the world doesn’t make sense to me, and I feel like I don’t belong - when the racism or exclusion is so ingrained that nobody else seems to notice that I’m falling further and further out of my body and out of the existence I inhabit on Earth. (wow, now that I’ve written all that out it seems really really dramatic - I suppose I need to GET OUT of my own head sometimes…)

Anyway... until next time!

Vedika

1 note

·

View note