Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

tumblr

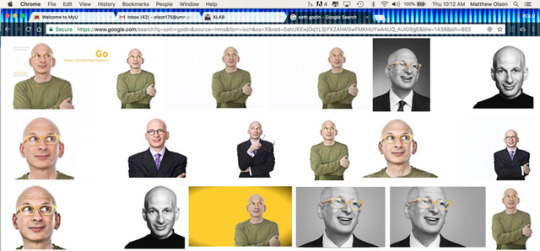

Open Practice is about wonder... which uses humility and love as its fuel.

Open Practice is uncertain... an uncertainty which is accurate and trustworthy.

Open Practice meets you where you’re at, when you’re ready to be ready.

It never fails, it’s never done... fluid, kind and accepting...

It uses language(s) but acknowledges its limits...

It prefers experience, which happens as stories that we participate in, we’re not the center of.

You don’t control it or anything.

You can’t. It bewilders you. It’s complex and simple.

An anthropologist who left his academic post at MIT in the anthropology department and struck out into the world to live with indigenous peoples who’d never been contacted before... he was gone for 25 years and no one heard from him. When he reemerged his colleagues were extremely excited to hear his findings. They were surprised that he was very reluctant to visit with them. He finally did. They asked him what he learned...

“take care of and love plants and don’t make much of your accomplishments.”

That was it.

True story. Just like this movie is.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A design practice. An art practice. A writing practice. Research practice. A seeing practice. A listening practice. Meditation practice. A connectivity practice. A peace practice. A don’t forget about everything practice. A staying out of my own way practice. The speak first / think later practice (more jazz than proclamation.) Furniture, objects, space, books, music, publishing, food, swimming, smiling, love, sharing, translation... And a remembering the ocean as the pathway back practice. A daily practice.

Like everyone though, I’m way too busy to be that busy. And, it’s impossible. So what emerges is an “open practice” which seems to manifest from what Wordsworth described as a “wise passiveness”. An intention of non-careless and gentle indifference that gives way to a kind of attention. An effort but one that remains unformed, or what Barthes has referred to as ‘the Neutral’, which baffles and outplays the paradigm. This attention is ready to be ready. It participates and then responds by evoking or stirring, rather than informing. Using the word faith makes me nervous but, doubting that the plant will grow towards the light rather than the wall seems foolish. And thus, trust as an action and a way of being is generally a necessary structural element of open practice. Trusting in these things that come to get us... the worlds that consistently and constantly open up in a flash or without any drama at all... they're so much easier to metabolize than all those things we want and wanted (what a bad habit!). It's when following becomes indistinguishable from leading.

Open practice is a form of awareness that knows and accepts ego and capitalism while avoiding them in whatever ways possible. Authorship, hierarchy, leverage, separateness, self. Open practice is not a stance against these things, as we’ve learned now that most often a reaction against invokes a reverse and perpetuates a confirmation of their power. Rather, it contains a built in resistance to them (more magnet to magnet, less oil in water.) Not against or anti but instead a consistent spirit of counter. Or as Svetlana Boym put it - “off” - meaning not Luddite but rather willingly ludic and accepting.

I find that I don’t know how to find the work I really want when I look for it. And this looking that comes from desire and expectation is inside our great unfolding, not outside. So by staying with the INT\EST\EXT I want to remember that both the umbrella and the kite function through an act of resistance, but one is about stopping and one is about starting.

And I know what open practice is if no one asks me what it is; but if I want to explain it to someone who has asked me, I find that it’s hard… luckily, open practice is also an attempt at integrity and it seems that if one is operating with openness and integrity, we are probably saying “I don’t know” and “I’m not sure” a lot.

By OOIEE for the SCI-Arc Public Lecture Series 2017 available as a poster through Studio-Set Margin series.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The World Is Made Of Stories

The American poet Muriel Rukeyser famously wrote that “the universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” We are not just animals that use language: we are storytelling creatures, for telling stories is a fundamental activity of all people in all cultures. The Canadian cognitive neuroscientist Merlin Donald expresses this well:

Language is basically for telling stories. . . . A gathering of modern postindustrial Westerners around the family table, exchanging anecdotes and accounts of recent events, does not look much different from a similar gathering in a Stone Age setting. Talk flows freely, almost entirely in the narrative mode. Stories are told and disputed; and a collective version of recent events is gradually hammered out as the meal progresses. The narrative mode is basic, perhaps the basic product of language.

Stories, then, are more than just stories. It is with our stories that we make sense of the world. We do not experience a world and afterward make up stories to understand it. Stories teach us what is real, what is true, and what is possible. They are not abstractions from life (though they can be that); they are necessary for our engagement with life. As the Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre puts it, “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”

Unaware that our stories are stories, we usually experience them as the world. Like fish that do not see the water they swim in, we normally do not notice the medium we dwell within. We take for granted that the world we experience is just the way things are. But our concepts and ideas about the world, like the stories they are part of, strongly affect our perception of reality. In Buddhist practice, one learns, early on and then continually, the truth of my favorite bumper sticker: “Don’t believe everything you think.”

This recognition may lead to the wish to strip away any and all accounts of the world and “return” to the reality behind them, to get back to the bare facts of experience. But that too is enacting a story, the story of “letting go of stories.” The point here is not to deny that there is a world apart from our stories; rather, it is to say that the way we understand the world is by “storying” it. Unlike the proverbial fish, however, we can change the water we swim within. Our relationship with stories can be transformed.

Stories are constructs that can be reconstructed, but they are not free-floating. In other words, we cocreate the world we live in. We need stories that account for climate change and enable us to address it. We cannot simply un-story global warming—although some fossil fuel companies have tried. Living according to certain types of stories tends to increase suffering, and living different stories can reduce suffering.

It is with our stories that we make sense of the world. We do not experience a world and afterward make up stories to understand it. Stories teach us what is real, what is true, and what is possible. They are not abstractions from life (though they can be that); they are necessary for our engagement with life. The central character in the foundational story that we return to over and over is the self, supposedly individual and real yet actually composed of the stories “I” identify with and attempt to live. Stories give my life the plot that makes it meaningful. Acting out one’s stories has consequences, a process that in Buddhism is called karma. From this perspective, karma is not something the self has; it is what the sense of self becomes as it becomes entrenched in its roles. Habitual tendencies congeal into one’s character—and one ends up bound without a rope.

There’s an important difference between improving one’s karma and realizing how karma works, which is to say, our problem lies not with stories themselves but with how we identify with them. One meaning of freedom is the opportunity to live the story I identify with. Another freedom is the ability to change stories and my role within them: I move from scripted character to coauthor of my own life. A third type of freedom results from understanding how stories construct and constrict my possibilities.

According to the British cognitive scientist Guy Claxton, consciousness is “a mechanism for constructing dubious stories whose purpose is to defend a superfluous and inaccurate sense of self.” The main plot of such stories tends to revolve around fear and anxiety, because the central character—“I”—can never achieve the stability and self-sufficiency that is sought. Such narratives attempt to secure and aggrandize an ego-self understood to be separate from the rest of the world.

Those efforts boomerang because, as Buddhism emphasizes, such a discrete self is delusory. Awakening involves realizing that “my” story is part of a much larger story that incorporates others’ stories as well. Our stories do not have sharp edges; they are interdependent. Like the jewels in Indra’s net, they are composed of other stories, recombined and internalized. I grow up by accepting some of the stories that society provides, and I reinforce them by acting in ways that validate them. Stories teach me what it means to be a boy or girl, American or Chinese, Christian or Buddhist, how and why and to what extent things like education, religion, money, and so forth are important.

The stories that make sense of this world are part of this world. It is not by transcending the world that we are transformed but by storying it in a new way. Or, to say it another way: we transcend our world by being able to story it differently. When it comes to religion, that means changing the metaphors we live by. Understanding religious metaphors and symbols in a literalistic way is a modern phenomenon that usually misses the point. In Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor, Joseph Campbell writes:

Half the people in the world think that the metaphors of their religious traditions, for example, are facts. And the other half contends that they are not facts at all. As a result we have people who consider themselves believers because they accept metaphors as facts, and we have others who classify themselves as atheists because they think religious metaphors are lies.

The metaphorical nature of religious language means that its assertions are difficult to evaluate. Myth, like metaphor generally, avoids this problem by being meaningful in a different way. Religious doctrines, like other ideologies, involve propositional claims to be accepted or refuted. Myths provide stories to interact with

77_Stories

The Buddhist myth about Siddhartha’s fateful encounters with an old man, an ill man, a corpse, and a renunciate can be taken as historically factual, or as an imaginative way to represent why Siddhartha left home, or as a literary device that may have nothing to do with the actual life of the Buddha. Yet the myth is an effective way to story his teaching. Understood symbolically, this polyvalence is not a problem, because that is how myths work. It is not a matter of literal truth or falsity. As Rabbi Akiva Tatz writes in Letters to a Buddhist Jew, “All my stories are true. Some happened and some did not, but they are all true.”

A better way to evaluate a myth—a symbolic story—is to consider what happens when we try to live according to it. The most important criterion for Buddhism is whether a story promotes awakening. A myth that is interpreted for me still needs to be interpreted by me, by what I do with it—and what it does with me. A story about the suffering of old age, illness, and death challenges the stories with which we try to ignore our mortality: the importance of money, possessions, fame, power. Letting go of those preoccupations opens up other possibilities: different stories, and perhaps a different relationship with stories.

Myths are not simply bad stories that need to be replaced with rational and scientific accounts that more accurately grasp the empirical world. From a story perspective, one of the most dangerous myths is that of a life without myth, the story of a realist who has freed himself from all that nonsense. The idea that science and systematic reason can liberate us from the supposed unreason of myth is one of today’s popular fictions.

Stories have social functions as well as individual ones. Some stories, for example, justify social distinctions. Medieval kings ruled by divine right. A Rig Veda myth about the various parts of the cosmic body rationalizes the Hindu caste system. We challenge a social arrangement by questioning the story that validates it. When people stop believing the stories that justify the social order, it begins to change. When French people no longer accepted the divine right of their king, the French Revolution ensued. “Change the stories individuals and nations tell themselves and live by,” writes the Nigerian poet and novelist Ben Okri, “and you change the individuals and nations.”

One of today’s dominant stories is that we live in a world ruled by impersonal physical laws that are indifferent to us and our fate. Human beings serve no function in the grand scheme of things. We have no significant role to play, except perhaps to enjoy ourselves as much as we can, while we can, if we can.

This story of a universe reducible solely to physical laws and processes has social applications as well. Evolution by natural selection undercut what remained of the West’s old religious story: God was no longer needed to explain creation. Soon after Darwin publishedThe Origin of Species, his theory was appropriated to justify the evolution of a new type of industrial economy. Herbert Spencer coined the term “survival of the fittest” and applied it to human society. You must crawl over the next guy on your way to the top, or he will crawl over you. The value and meaning of life were largely understood in terms of survival and success, the measure of which was mainly financial, not reproductive. In this story, life is about what you can get and what you can get away with until you die. You’re either a winner or a loser, and if you aren’t successful, don’t blame anyone else.

The stories that make sense of this world are part of this world. It is not by transcending the world that we are transformed but by storying it in a new way. Or, to say it another way: we transcend our world by being able to story it differently. Not coincidentally, Spencer’s social Darwinist story appealed most to the most powerful. Industrial tycoons such as Andrew Carnegie embraced his philosophy. As did John D. Rockefeller, who in a talk to a Brown University Bible class justified his business principles by comparing them with cultivating a rose, which “can be produced in the splendor and fragrance which bring cheer to its beholder only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it. This is not an evil tendency in business. It is merely the working-out of a law of nature and a law of God.” It is not clear whether the pruned rosebuds refer to Rockefeller’s competitors or his employees, but we can be sure who the splendid, fragrant rose was.

Obviously, the basic outlook of social Darwinism—that one should pursue one’s own economic interest even at the cost of others’ well-being—is still very much alive and thriving. From a Buddhist perspective, it seems equally obvious that this story rationalizes some very unsavory motivations, including the “three poisons” of greed, aggression, and delusion. It is the deluded belief that one is separate from others that permits one to pursue one’s own interests indifferent to what is happening to those others.

Sociologists have pointed out that a social application of Darwinism confuses impersonal biological processes with more reformable social arrangements. But if enough people believe in that story and act according to it, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. We socially construct the world according to those principles and society in turn does indeed transform into something like a Darwinian jungle. Using natural selection in that way becomes a Kipling-like “Just So” story along the lines of “How the Leopard Got Its Spots.” Such tales typically begin “Long ago on the African savannah” and become a game of finding the evidence for the worldview we want to buttress: “And that is how we came to be how we are now.”

As I write this, a new Oxfam report states that in 2014 the richest 1 percent owned almost half the world’s wealth (48 percent), while the least well-off 80 percent owned about 5 percent. If this were happening in accordance with basic socioeconomic laws—well, we may not like such a development and might try to constrain it in some way, yet fundamentally we would need to adapt to big disproportions. This is how a social Darwinist type of story can “normalize” such a disparity, with the implication that it should be accepted.

But there are alternatives. Instead of accepting such a story—which serves only to rationalize the growing wealth and power of a privileged elite—we can look for better ones, better because living according to them would reduce social dukkha, or suffering. Collectively as well as personally, our stories can change, and in this case must change, so that we can better respond to the economic and ecological challenges that now confront us.

In the pluralistic climate of contemporary life, the foundational narratives that served us in the past—religious and secular—can no longer be understood in the same ways. We can retreat into a parochial framework that views only one worldview as true, or we can embrace the multiplicity of stories and perspectives in a spirit of playful nonattachment. Knowing that we live in a world made of stories, we can, in the words of the Diamond Sutra, “let the mind arise without fixing it anywhere.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

We talked a bit in class about a scene from the movie Adaptation (directed by Spike Jonze... more on him in a minute). This scene is based on the real life Robert McKee - an expert in storytelling - and you may remember that when I was working in advertising I studied his ideas a bit. One thing that shines through in this scene that is worth adding to our list of storytelling marks is commitment. Commitment in a sense which is related to passion and trust as Sister Corita Kent put forth in her suggested rules.

Spike Jonze is a fascinating character. He started his career making skateboard videos with cheap cameras. Very XLAB don’t you think? He seems to effortlessly ride a line of doing ridiculous things like this while also doing Her, Where The Wild Things Are, Three Kings, and Adaptation. But then also doing the video for this song (which, if you’re interested, was involved in the best live music moment of my life... ask me.)

The reason I share a bit about Spike... we need to remember that great storytelling isn’t something you figure out, it’s something you do. And that’s another great mantra for the XLAB... do, do, do. Because the reason Spike is an amazing story, is because he’s an amazing person... not by luck, but by action.

The story of your work and your work are not separate things.

Here’s an interview with Robert McKee in Harvard Business Review.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

My favorite song from the Belle and Sebastian record “Storytelling” <3

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

The woman Tuesday we touched on Sam Mockbee and his practice of assuring his students they wouldn’t make anything interesting until they’re at least 50. I noticed Hailey referenced the spirit of what we were discussing… and Alden asked me some questions after class about overthinking that seem related too… but I wouldn’t have necessarily decided to post this or follow up unless the following happened:

Last week I bumped into an article from Inc. Magazine about books and why one should surround themselves with books even if they’ll never read them. The article referenced Umberto Eco and his massive personal library. I’ve been interested in Umberto Eco ever since a friend said he shared some really similar beliefs about life and creativity. The article points out that even though Eco will never read most of his 30,000+ books, it is good that he is surrounded by them. So in honor of this, I pulled my Eco books down from my library and am going to have them around in my more immediate space for a while. See what happens :-)

When I Googled to find this Inc. article - of course - I found other things... there is a site/blog/project called Brain Pickings (not a very good name or graphic design) that has a nice post about Eco’s library. If I were you? I would sign up for the email list on this site too. Usually on Sunday an email comes with a glimpse of the posts that week. I’ve never once received one and not found something of interest there and generally end up reading them all.

The woman who started this site Brain Pickings is very XLAB. She was working at an ad agency when she... well, do some research and learn about her. She very much followed her inspiration out of herself and it ended up creating a life and work for her that is really inspired and living.

(Relevant echoes related to Eco... Roland Barthes was a good friend of his and we’ve referenced him a lot... Eco believed “Read books are far less valuable than unread ones.” which could be a mantra for the XLAB?... What else? Can you find anything that seems to be important to what we’re doing here?)

And back to the top, what about Eco’s advice to young artists? [:-)

0 notes

Photo

THIS MADE ME HAPPY [:-)

In Oliver’s librarian selfie we encounter a friend of mine named Jessica Shaykett. She was the archivist and librarian for the American Craft Council for years and I worked in their archive a little bit doing research on some ideas I’m interested in about the boundaries (imaginary) between art and craft. I got to know her a little better when that organization invited me to participate in a symposium and workshop series they were co-sponsoring at the Savanah College of Art and Design (aka SCAD). It turned out Jessica worked at SCAD too.

She’s pretty amazing. Maybe you should watch that video of her? Her story and the evolution of her work and interests is something we could talk about. (The sound in the video isn’t great but…)

Just for fun, thinking back to my visit to SCAD, I believe the talk I gave was called “I Love My Life, I Made It Up” and the workshop I did with the students was creating a tour of Savanah based on sound. It was a super great and moving project. If you’re interested, ask me about it sometime.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Did everybody see Seth Godin’s post the day after I recommended his daily email to you guys? Pretty timely. I wrote and told him about you guys and what we’re trying to do. He thought the synchro was pretty magic and thanked me for doing the class :-)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There are lots of reasons for the XLAB to spend some time getting to know Vito Acconci. He passed away recently but was truly an trans-disciplinary thinker and doer (to use Yaniv’s term). He became famous as an early and radical performance artist in the 60s/70s but then transitioned into all sorts of different things finally becoming a landscape architect. (He’s somebody you should all know about like Robert Irwin, who also began with art and became a landscape designer hint hint :-)

But the reason I think of him today is library related. Please have a look and let me what you think about this different way of thinking, organizing and thus interacting with a library means.

By organizing his library around ontological themes… do we learn something deep from his very famous Following Piece (1969)?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Don’t forget, Laurel Broughton is visiting class today at 3:30! Psyched.

PS. Here’s how I described the class to her:

The class is a sprawling set of provocations and explorations related to architecture, design, art, fashion, music etc. There are no real assignments or tests, just a few requirements like mandatory class attendance and two self-initiated field trips a week... as proof of their outings, each student must share a selfie taken with a librarian, archivist, museum guard etc :-) In, and with, the spirit of Black Mountain College we’re examining 'cross-disciplinary, open practice' through historical examples and present practitioners (like you)... from the Eames Office to PIN-UP Magazine to Yamamoto. We look at manifestos or guides like “How To Work Better” Fischli and Weiss and Sister Corita Kent’s “Rules”. And we have a few visitors in class to make it clear this approach is within reach.

It's a really wonderful journey though the students are often frustrated because they lack experience being self-directed but, mostly (I think and hope) are baffled and puzzled in a joyful, poetic way. I created this class as a reaction to students I've hired over the years who’ve seemingly lacked an ability to think for themselves, create motion on their own and/or have difficulty in understanding the difference between information and insight. Often they're unable to locate or express a genuine POV? I try to share with them the notion that they can use love and curiosity as their guide... and as a practice. As a way of being.

0 notes

Photo

Seth Godin is a business and marketing thinker. That’s a description that would likely leave me cold normally but, Seth is a surprising character. He embodies the spirit of the manifestos we’re going to start using (thought we’re not going to call them manifestos right? Suggested Parameters?) Ways of Being lists? What should we call them?) He has that weird mix of originality - which only emerges through humility and openness - common sense and approachability, which most often leads him to truly innovative ideas.

Most of you guys seemed surprised to learn that when I’m hiring and interviewing, I’m not really that interested in young people’s portfolios. I look and assume they’re fine but, prefer to attempt to gauge a persons curiosity, appetite for growth... will they contribute something... are they empowered?

Seth Godin understands this.

Please sign up for his daily email. You will learn something from 85% of them.

0 notes

Photo

There’s a new DIS video. It’s almost perfect for this moment in XLAB? So many aspects to be seen through the lens of ‘open practice’ and so much thought that is out of the ordinary... which points on the manifestos are they hitting here?

0 notes

Video

youtube

In the spirit of Bruce Mau’s proposal 2. Forget about good... I present Sun Ra’s Make Another Mistake.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sister Corita Kent is a fascinating character in art history. Part activist, part artist, part social critic, part Catholic nun... a great spirit animal for the XLAB. These rules she wrote are not only “true”, they are true.

They were made popular by John Cage who comes up a lot. The rules have often been attributed to him but they weren’t his in that sense. I’m sure if he were still alive he’d love that situation for its inaccurate accurateness?

“THERE SHOULD BE NEW RULES NEXT WEEK”

But what if we can devise a practice that never evolves past potential? That’s the problem with rules right? They suck. So how can we embody these lists but keep them as a “coded mist” of meaning? My friend Frank Gilbert Lyon II uses that term... coded mist... which I think of as a way of pointing towards or describing all the things we know but don’t need to think about...

What are we to do? Do you ... do you have any idea?

Seriously... I want to know.

0 notes

Photo

How to Work Better (1991) is a well-known work by Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss. It consists of a ten-point manifesto that the artists found, enlarged, and had painted on the side of a building in Zurich. Their instructions are meant as a self-motivating reminder and description of their own process as artists, but are also directed to the rest of the world as a propositional code of conduct or ethic of behavior — in fact, a copy of How to Work Better is pinned to the wall of countless artist studios around the world, as well as above the desks of many curators, including this one.

The question of how to work or how to behave is one that lies at the root of all of our decisions. To rehearse a common truism: it’s not just what you do, it’s how you do it — it’s not just what artists or curators do, but how they behave when they do it. Beyond the different styles, techniques, or themes that characterize their work are the different codes of conduct that guide the way they act or behave. The same could be said of museums or art institutions: running alongside the question of what they are showing is the question of how they are behaving.

In recent years, small organizations around the world have been formulating different answers to that question. They are taking risks not just with what art to show but also with how to work and how to behave as an institution. In other words, in addition to having an adventurous and forward-thinking curatorial program, they are experimenting with new institutional and curatorial methodologies that articulate a new ethic of behavior and a new code of conduct. As a result, they are outlining a context for what it means to propose an alternative today. My own effort towards this, with The Artist’s Institute in New York, is but one proposition among many others.

With mainstream museums and commercial galleries often showing uncommercial work by uncommercial artists, the role historically played by alternative spaces has been made somewhat redundant. Now is a time when MoMA shows performance art, the Whitney shows site-specific art, the Guggenheim shows institutional critique, and the New Museum shows artists who are Younger Than Jesus (2009). Commercial galleries such as Reena Spaulings or Alex Zachary allow the most prominent collectors to buy work by the most uncompromising artists. And those smaller organizations that manage to stay non-profit and independent soon find themselves invited by the Tate Modern’s “No Soul for Sale” (2010) or the ICA’s “Nought to Sixty” (2008).

While these mainstream or commercial structures might take risks with what they show, few take risks with how they work. In most cases, they produce exhibitions, one after the other, and strategically compete for larger audiences and for more widespread recognition. The challenge for a contemporary alternative space or curatorial approach is to behave differently.

For example, the logic and structure of exhibitions could itself be called into question. Much of the difficulty with making an exhibition lies in the fact that to extract something from circulation — an object, image, practice, or idea — and interrupt it, examine it, and exhibit it, is to do it a great injustice. The philosopher Bruno Latour, among others, discusses the life of things, referring, in the largest sense, to all that which is usually not considered to be cognizant human subjects: objects, pictures, rocks, animals, natural systems, etc. These things, he argues — objects, images, and ideas included — have their own agency and won’t simply sit still under someone else’s microscope, on someone else’s terms. In fact, what makes them compelling is precisely what animates them, what they want, and how they behave when they are set loose into the world. In other words, objects, images, and ideas have lives to live, and instead of conceiving of an exhibition as a way to reign them in and use them to carefully prove a point, an exhibition could be something much riskier: a way to discover, along with the audience, how that point will behave and where it will wander as it lives its life. In this sense, the opening of an exhibition could mark the beginning of a curatorial idea, not its end.

Traditionally, it’s the other way around: curators open their shows and play the role of explicators, working to enlighten visitors who don’t know what they know. They are expert performers of the I Know and avoid displaying any sign of the I Don't Know. Instead, an alternative curatorial behavior could be to embrace a more vulnerable relationship to knowledge. An institution could stop behaving like an explanation machine, where those who know are teaching those who don’t know, and invest in what philosopher Jacques Rancière calls the equality of intelligences1, where those who know something engage with those who know something else. It’s not about preparing explanations in advance, but about following the life of an idea, in public, with others.

Clearly, the goal is not to reject the expertise of the I Know in favor of the anti-intellectualism of the I Don’t Know, but to step outside of that binary entirely. Following the art critic Jan Verwoert2, it means performing both the I Know and the I Don’t Know in the key of the I Care. Verwoert suggests the I Care as an act of giving what you don’t have to people who don’t want it, or, in other words, as an act that is more affective than it is effective. If an institution goes from knowing to caring, it could point to the affective relationship that ties people to ideas and become a place for attachment rather than consumption. After all, the ideas that make us curious are not the ones we fully understand, but the ones we care about — I Love It is always more compelling than I Get It.

In unpacking the I Care, Verwoert also points to the importance of the figure of the muse: he or she who inspires and influences you — or, etymologically speaking, who amuses you. Funnily enough, one tends to think of the curator as being the artist’s host, inviting him or her into an institution, but it’s actually the other way around: we are the guests of the artists we choose to work with. In that context, like for any other houseguest, we should find a way to say Thank You. An exhibition could be an homage instead of a lesson—a way to thank artists, not dissect them.

Curatorial responsibility involves the invention of ways to appropriately pay tribute to the lives of artworks and artists—not the invention of curatorial methods for their own sake. By always putting the artist first, a good exhibition behaves like a guest who takes care to do whatever is true to the spirit of the work.

To pay homage to someone falls somewhere between admiring them and studying them. A tribute is neither an analysis nor just a party. Giving a toast is about making people care, not about making them understand. The act of appreciation, by nature, is not didactic — it’s what you like, not what you know — but it is social: it involves not just what you like, but caring about it so much that

1 See Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, Stanford University Press, 1991

2 Jan Verwoert, "Exhaustion and Exuberance," Dot Dot Dot 15, 2007, p. 89-112.

you want to share it with others. It’s more than naming a favorite book, it’s recommending it. The affective curatorial approach of the I Care can inhabit that space between an homage and an explanation, between a tribute and an analysis, between a recommendation and a nomination. Once again, this is a place where the I Know co-exists equally with the I Don’t Know, in the form of the I Care. While the uptown museums conduct their art historical power games and the downtown galleries conceive their elusive tactics and smart chess moves, those eager for another model could perform the vulnerable, dangerous, and radical act of wearing their heart on their sleeve.

While behaving in the key of the I Care can be an act of celebration, it can also be one of critique: the art of the toast is closely aligned with the art of the roast. An alternative and affective curatorial behavior involves the biting quip and critical edge of parrhesia — to use a term resurrected by Michel Foucault3 — or fearless speech. To practice parrhesia is to have the courage to speak frankly from a position of exposed vulnerability. Unlike the careful and calculated strategies of a much safer practice of rhetoric—the debate of differences between equals — parrhesia involves a willingness to stand for irreverent or critical values from the perspective of a less powerful member of the community, and is certainly relevant to those smaller and more vulnerable institutions.

To care also means to take care and to pay attention, and in order to properly do that, as argued by philosopher Bernard Stiegler4, we need to slow down and take our time. While museums build more buildings, produce more exhibitions, raise more money, place more ads, and hope to draw more crowds, another model could be to do less and spend more time with what we do. Rather than feeding the conveyor belt of the next, next, next, we could stop channel surfing and demand a more focused and sustained attention span. One way organizations do this is by simply repeating themselves: year after year, the commercial gallery Miguel Abreu in New York, for example, repeatedly hosts a screening of films by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, insisting on their sustained relevance to the gallery’s identity and program as a whole. Another way many organizations take their time is by emphasizing research over exhibitions: if exhibitions traditionally last six to ten weeks, research-based initiatives allow for the pursuit of speculative questions over longer periods of time, leading to more in-depth and textured thinking. BAK in Utrecht, for example, commits several years to thinking through a single theme through exhibitions, publications, conferences, or private roundtables, all placed on equal footing. Mamco in Geneva, although far

3 See Michel Foucault, Fearless Speech, Semiotexte(e), 2001

4 See Bernard Stiegler, Taking Care of Youth and the Generations, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010

from being a smaller alternative space, conceives of an exhibition as a single program that evolves over several years, made manifest in a series of episodes. Another mainstream yet relevant institution, the Dia Art Foundation in New York, not only presents single exhibitions that last a minimum of eight months, but is also committed to maintaining (and caring for) expensive long-term projects such as Walter De Maria’s The Lightening Field (1977) or Earth Room (1977). While many galleries and art centers seem seduced by Hans-Ulrich Obrist’s dontstopdontstopdontstop (2006), others aren’t, and prefer to stop.

The media, of course, always favors the fast and the furious. Therefore, stepping off the conveyor belt also means falling out of the news cycle, and behaving this way will inevitably draw smaller audiences. This smaller scale does come with several advantages: not only is it much cheaper to maintain a smaller physical space, but this intimacy will also favor a face- to-face encounter and demand a more active and immediate engagement. Organizations such as Salon Populaire or Silberkuppe in Berlin, Kunstverein in Amsterdam, Pro Choice in Vienna, Front Desk Apparatus in New York, castillo/corrales in Paris, or New Jerseyy in Basel are no larger than 100 square meters, and are designed with that very characteristic in mind.

Since they invest in face-time rather than in ad-time, these small institutions build their audience as the result of a self-selecting process. In other words, the people who pay attention are not the ones who are encouraged to do so, but the ones who choose to do so. Since anyone is invited to attend any of the exhibitions or events, this is not a case of speakeasy or strategic exclusivity, but it effectively creates a space for self-selected and engaged community of people who care. The goal is not to engage in a competition to attract more audiences, but to establish a smaller gift economy for anyone who is curious enough and makes the effort to come by for a visit, whether a friend or a stranger.

More than anything, the challenge for a contemporary alternative space today is to behave the way Martin Luther King Jr. called upon all people to behave: to be maladjusted. By evoking a term usually associated with a psychological defect or illness, Dr. King famously declared that he was proud to be maladjusted, and that he would never adjust himself to a society that discriminates against racial minorities. In the art context, these smaller institutions are proud to be maladjusted: they do not adjust themselves to an art community obsessed with knowledge, power, and scale. Instead, they step onto the smaller and more vulnerable roads and allow learning to replace teaching, camaraderie to replace competition, the homage to replace the explanation, and the dance move to replace the chess move.

As a tribute to Fischli & Weiss, let me conclude and summarize by proposing an updated set of instructions for a contemporary ethic of curatorial behavior. It could certainly hang over the desk at The Artist’s Institute. (SEE 2ND IMAGE)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

How To Work Better - Fischli and Weiss remixed by curator Anthony Huberman

In the post about the Incomplete Manifesto for Growth project by Bruce Mau and company, there’s a link to a PDF called “How To Behave Better”. It’s a short essay by Anthony Huberman, a thinker who has had a large impact on me. PLEASE READ IT [:-)

“How To Behave Better” emerged from another essay by Huberman called Take Care. I’ll post it next. There’s so much stuff in it that has inspired the XLAB. PLEASE READ IT [:-)

I wish I’d have seen this. I wonder if there’s a video of it somewhere? It seems to allude that there is.

0 notes