Personal blog full of random musings on game design and beyond! Tom works as a developer at BetterUp Studios and previously worked at Inkle. @tomkail

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Authoring and testing haptics

This post is a 101 class on designing vibrations for apps and games, with a special focus on developing in Unity for playback on iOS.

I've recently had some time to spend exploring haptics in Unity for an iOS app we've been working on. I've previously designed haptics for PS4 and Switch and wanted to write a sort of Haptics 101 to help others get started. The technology is incredibly effective for improving game feel, but is often ignored by developers.

What are haptics?

The technology shared by your iPhone (Taptic Engine), Switch Joycons (HD Rumble) and PS5 controllers (Dual Sense) is just a rebranded Linear Resonant Actuator (LRA). These things are ubiquitous now; they're in every modern console, VR device, phone and smart watch; and are even being put in cars and kitchen appliances.

LRAs are tiny, cheap, and allow for far more precise and controllable vibrations than in earlier hardware, and when done properly can make basic interactions feel incredibly satisfying - especially interactions that don't use a button (pressing a clicky button has a similar feel).

A LRA can be thought of as a sort of speaker, as it plays a waveform of a given length that has magnitude and frequency. The ranges of these vary from device to device (for example, the iOS Taptic Engine has a frequency range of 80-230hz). This allows for haptics that have a feeling to them. A haptic could be "snappy" (short, high magnitude, high frequency), "heavy" (a bit longer, slightly less magnitude, low frequency"), or "muted" (mid-length, medium magnitude and low frequency).

Examples

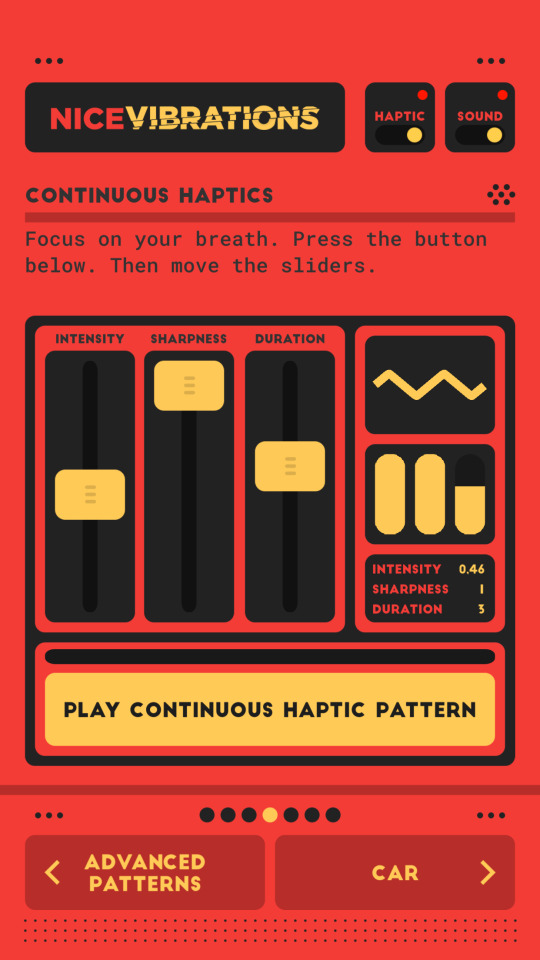

On the iPhone, you should check out the demo for Nice Vibrations.

On Switch, get a copy of 1-2 Switch, which is a glorified tech demo.

On PS5, Astro's Playroom comes with the console.

On Meta, play Asgard's Wrath 2. Many of their effects are testable with their freeware editor software described below.

State of haptics

You will note that console launch title games remain the best examples of haptics! Despite them making a massive difference to feel and being relatively easy to implement, most games and apps today make little to no use of haptics. Here's my two cents on why:

You can't "see" haptics, and thus they don't build hype like shiny graphics do. Reviewers tend not to mention them beyond exceptional cases.

Audio is similar, but is still communicable in video marketing, is expected by players, and is a fully mature field with no shortage of experts. Any decent size studio has an audio department, and yet even in this case audio tends only to get added towards the end of development once the game systems and visuals are established.

None of this is yet true of haptics. I've never heard of a dedicated haptics department, or even a "haptics expert" (although it's probably one a few CVs somewhere). It's simply left to one or two designers or developers to chuck something together at the end of a project. I imagine it's hard to convince producers even to do this, given that the end of development tends to be when the implementation team is busy simply getting the product functional.

This is why despite Nintendo, Sony, Apple and Meta having each put significant resources into haptics, they've struggled to convince other developers to really invest the time.

Haptics are notoriously difficult to test. A musician can immediately hear their work, but haptics requires special hardware that leads to painfully slow iteration.

This final point offers a glimmer of hope - in recent years software has been released allowing for rapid creation and near immediate testing.

Types of haptic

When designing, there are two types of haptic to be aware of. These have different names on different platforms; I'll give them all.

Transient/Emphasis haptics are very short pulses that feel like clicks. If you simply want to make tapping around your app feel nice, or want to juice your game's gun trigger button, just play one of these. iOS comes with a few presets that Nice Vibrations have copied.

Continuous haptics allow you to turn on vibration and keep it going while modifying the intensity/frequency. By controlling these you can (for example, as I did on 80 Days), model the "feel" of a sphere being continuously rolled as the player drags it around. On some platforms this is implemented like real-time audio, by updating a buffer of samples to be played in the next frame, and thus can be quite fiddly.

Designing and testing haptics

Each platform has it's own native format and API for designing and playing haptics. Console ones are NDA'd, so that's about all I can say about those, except that in all cases they're rather difficult to test because they only play on device - you can't test native haptics in the Unity editor.

Nice Vibrations

For this reason the first tool I'd recommend is Nice Vibrations. This tool allows you to design haptics once and play everywhere.

Nice Vibrations comes with some basic default haptic effects, and some ability to control a single continuous haptic effect (note that there's a bug on iOS meaning you can't change sharpness dynamically, although you can change intensity).

Haptics have to be felt to be understood! Stop reading this and check our their free iOS demo on the app store. Come back when you're done.

Wasn't that nice?

If you simply want to make your app feel nice when you press buttons, call HapticPatterns.PlayPreset(HapticPatterns.PresetType.Selection); If you're not making a game with complex haptics, this will make your app feel significantly nicer to interact with and you can stop reading this article here.

More Mountains, the original developer of Nice Vibrations, deprecated their original vibration code in favour of an implementation by Lofelt. Lofelt were then bought by Meta.

Haptics Studio

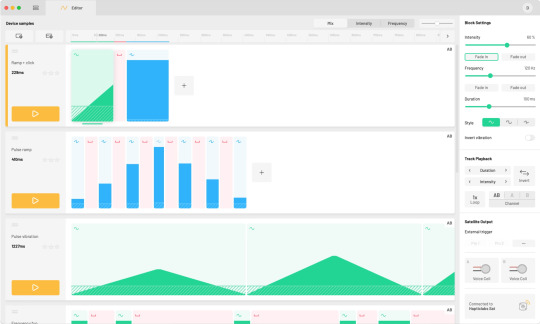

Meta then released Lofelt's editor, Haptics Studio, for free for use with the Quest (although they swapped the tool that made them easy to test on mobile for one that made them easy to test on Quest).

Haptics Studio is excellent, as it allows you to easily edit on desktop and immediately test haptics via Quest controllers, without requiring you to wear the headset once the app is launched on the device. You can then export to .haptic or as of 2024, .ahap (I asked for them to add this functionality, and I'm deeply grateful to their team for doing this).

They have lots of wonderful demo haptics from Meta's own games, which are almost entirely made by converting sound effects to haptics. Both play at once when you test.

If you simply want your game's actions and events to feel nice, then you probably just want to use this software and convert your sound effects to haptics and play them together. This is all you need to have a game that feels better than almost anything on the market aside from 1st party titles.

Note that Quest 2 controllers can only play at one frequency and thus lack "sharpness" (something that isn't mentioned in the software).

If you're serious about adding haptics to your game, I'd suggest buying a Quest 3 and building haptics here.

Hapticlabs Studio

If you don't have a Quest but do have a Mac and iOS device then you can use the similarly-named-but-entirely-different Hapticlabs Studio. Hapticlabs make their own actuators for developers of hardware, but also have best-in-class software that allows you to author on Mac and immediately test on iOS. It shows when you try to play frequencies not supported by iOS.

This software is beautiful and functional and I'd recommend it for when you need to design a single simple but perfect effect (think the effect that plays when you pay on iOS), although currently requires an invite to use. I've found the devs happy to share invites if you ask.

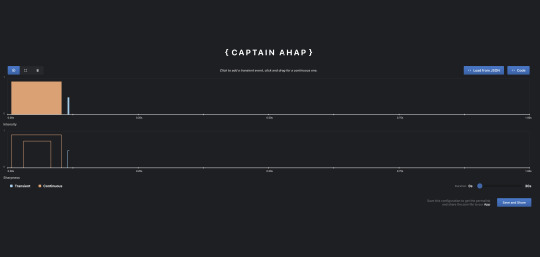

Captain AHAP

A less good way to build and test haptics is the web-based Captain AHAP. It requires iOS but not a Macbook. You use their app to run haptics designed on web. It's not a very good editor, but it's functional and a decent way to see what iOS is capable of.

A few general tips

If you are making an app, add built in effects to all buttons and call it a day. If you are making a game, do the same but also add them for player actions, and consider adding them for reactive effects like footsteps only if you have spare time and a special interest.

Broadly, haptic design is VERY similar to audio design. If I were to set up a large game studio, I would pass my haptics design tasks to a member of the audio team.

When mixing audio, good advice is to separate frequencies taken by the various instruments so they can all be distinguished apart, giving a cleaner sound. This is especially necessary with haptics, as our ears are far more sensitive than our touch receptors. Fortunately for designers, haptics thus work best when they are simple and clear. You rarely want more than one effect playing simultaneously, and if you do they should occupy distinct frequency spaces.

Haptics can get tiring and should be used in moderation. The exceptions to this are almost always games designed explicitly to show off haptics. That is unlikely to be your game, and nobody is handing out awards for experimental haptics design. In most cases you should aim to build something that players don't notice at all, but miss as soon as it's turned off.

You almost never need continuous haptics. They are always tempting but especially time consuming to implement and can easily feel annoying.

0 notes

Text

Understanding Unity's audio sample system

TL;DR

When Unity refers to "samples", it pretends that the audio clip is mono. The documentation on this is sparse and what exists is misleading. The result is that when using audio buffers, the number of channels must be taken into account.

The following will break this down further, and is confusing but still less confusing than trying to read the Unity docs. Enjoy.

Sample Count Basics

audioClip.samples and audioSource.timeSamples count the number of samples in a single channel. This means that a sample in this range can be calculated by multiplying time and audioClip.frequency; note that we do not need to multiply by the number of channels.

Issues with Multiple Channels

The issues begin when we have more than one channel. Unity's documentation claims audioSource.timeSamples is "Playback position in PCM samples." However, this appears not to be accurate.

According to this documentation on PCM (https://larsimmisch.github.io/pyalsaaudio/terminology.html), it actually describes what PCM would call a "frame"; a single sample in each channel.

Increasing the number of channels does not increase the number of frames, but it does increase the number of samples.

Going forward, I'm going to use the PCM terminology.

Real Sample Count in Multichannel Audio

When more than one channel exists in an audio clip, the real number of samples in the clip is the number of samples for a single channel multiplied by the number of channels.

Unity doesn't make this distinction particularly clear, which can be confusing when using functions that deal with sample data arrays, such as audioClip.GetData or OnAudioFilterRead. These functions deal with float arrays with a length equal to audioClip.samples multiplied by the number of channels.

Practical Example: Using Get/SetData

Let's look at how this works in practice, using the audioClip.Get/SetData functions, which take two arguments:

The first is data, described as "an array with sample data from the clip".

The second is offsetSamples, which isn't described at all. (sigh)

The key is that data always refers to PCM samples, and the term samples as seen in offsetSamples always refers to PCM frames.

Why Unity's Approach is Misleading (But Helpful)

Unity's documentation is unclear and misleading, but their approach has an advantage – when describing samples we can typically ignore channel count.

Interleaved Sample Buffers

Unity's sample buffer uses interleaved channels. This means that a buffer of 16 frames of 2 channels, left (L) and right (R), will look like this: LRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLRLR Clips with more than 2 channels would be interleaved in the same manner. For those interested, the other method of handling channels is a planar buffer, which would look like this: LLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR

Floating-Point Values

Sample buffers store floating-point values between -1.0 and 1.0.

Microphone Functions in Unity

Unity's Microphone functions all record in mono. Microphone.Start will return a clip with a single channel, and Microphone.GetPosition will return the number of samples for a single channel.

Bonus: Direct Audio Output to Speakers

A neat trick I stumbled upon on the way was how to send audio to a specific speaker in a (for example) 7.1 setup: https://thomasmountainborn.com/2016/06/10/sending-audio-directly-to-a-speaker-in-unity/

0 notes

Text

Randomising item names

Just a musing, this one.

Take an open world game with lots of unique collectable flora; MGS5, WOW or Zelda. Now, imagine that the names of the plants were different for each player; each game generating their names on the creation of a new save, or forcing players to write their own names for plants as they encounter them.

Why do this? To deliberately break down communication between players. I'm quite sure this would prove frustrating, in the way that removing efficiencies always is; but in exchange discussion of the game would become richer, and the world more mysterious.

As far as I know this has never been done (except in real history!) in a game. I'd love to see how it would play out, but here's some things I think we could expect to see:

Players would be forced to consider the appearance and uses of items

Designers would spend more time considering the appearance of items, and how players are able to inspect them

Items could even have minor variations to them to make identification more difficult

Players would create (likely very descriptive) names for objects themselves

Items with shared properties (for example, two similar-looking blue flowers that both induce sleep, except that one of them is also toxic and only found by rivers) require deeper understanding and more complex descriptions.

Wikis would become very difficult to use

Field guides would prove more effective as static documents

Communication with other players would become a more desirable means of gaining knowledge

AI would be effective too - something to consider as it becomes a new system game designers can make use of!

Items would be more opaque to new players, and they will initially ignore or undervalue objects - this is likely prove frustrating, since it undermines how games normally work.

As players continue to play, their interest in the system will increase, and eventually their understanding will prove rewarding and afford higher levels of skill.

Communication itself becomes a high-skill activity that can be improved with game and meta (understanding how other players perceive items) knowledge

Especially in online games, expect the community to coin static language for each item. This would likely undermine some of the effects of the design

Designers might be inclined to fight back against the freezing of terminology by changing items over time; although I suspect this would prove frustrating to the community unless a good excuse existed for doing so.

This is a design that requires a complex game around it; I suspect it'd be difficult to build a game around by itself. If we see it, my guess is that it'll come out of a more hardcore game or out of the indie space.

This is not an immediately lovable piece of game design, but I'd wager that it'd create a strong community and a game that is remembered for being unique.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Potential in games

The lens

"Critical potential" is a fundamental design principle related to risk/reward, pacing, and balance. It describes situations in games that enable a player to gain a huge advantage from a single action. It's almost universally common, although rarely discussed in isolation. It can be a useful lens when your game feels "flat", or if it feels too random.

Some more thoughts

I started thinking about this lens about a year ago, and I've since noticed it everywhere.

The game that clued me into this is Beast Breaker, although it’s a core aspect of the entire Breakout genre; and as we'll see, most games!

In Breakout, most paddle hits cause the ball to hit a block and return. However, by trapping the ball in a maze of blocks it's possible to get tens of hits in a small timeframe. It's hard to pull off, but has a massive payoff.

youtube

Almost all games contain some sort of "critical potential". Headshots in Counterstrike, a well-placed shot in Angry Birds, shooting the moon in Hearts. A slim chance at a large reward drives players to keep playing and find ways to cause it to occur more often. Without this drive, games can feel "flat".

This reward is sometimes paired with a risk; missing a headshot means you'll likely miss the target altogether. Come one card short of shooting the moon and you take 25 penalty points. This tension can be one of the most exciting elements in a game.

Although this is an element of games in all genres, the source of the critical potential may come from either luck, skill or investment (often time, but this could be money, social capital, or whatever else); or in many cases, a combination. The rate and scale of the potential rewards are driven by the game's design goals.

This is a difficult topic to discuss in the abstract, so to close out, here are some examples to consider.

Peggle is primarily driven by luck. Why does being rewarded for things that are largely out of your control still feel compelling?

Many boss fights have a weak spot that can be destroyed, dealing massive bonus damage. Compare this to similar boss fights without this.

A classic example is critical hit systems in JRPGs. Typically this is luck-based, but derived from stats that are slowly built up over the course of the game. Consider how critical hits feel for players at different points in a game that can be played over tens of hours.

Scoring systems allow designers to control how rewards are given. How can they be designed to reward very high levels of skill?

The nuke killstreak reward in COD:MW2 would immediately win the game for a player who could reach it! However, it was removed from later entries. Why?

Why might a designer not wish to add a risk of similar weight to the potential reward? Consider how this differs if the potential originates from luck, skill, or investment.

League of Legends is famous for allowing players to "snowball", making them effectively unkillable. How does this make players on both sides feel? Consider how it makes them feel as they enter a game, as well as while in the middle of one.

Physics systems can create a high level of unpredictability and are a cheap way to add luck-based potential. How do games like Angry Birds enable skilled players? How could you reward skilled players more?

Conversely, rule-driven games like turn-based tactics are often very predictable. How can critical potential be added?

Games without much critical potential can feel "flat". Are there examples of games where this "flatness" is a positive feature?

Critical potential is a staple in gambling sector. Why? How does their design differ from non-gambling games?

The hope of drawing a great hand in poker is one of its most compelling features. How can other games with input randomness create a higher or lower sense critical potential?

I've focused primarily on how critical potential feels, but it can also make game balance tricky for designers to control. How can designers balance these two conflicting priorities?

I hope any designers reading this find the lens of critical potential handy when crafting exciting feeling games!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catching up with VR!

I’ve been given a Quest 2 to muck around with! It’s been a many years since I worked with VR, and a few since I got PSVR. Both experiences left me fairly skeptical about the short term (~5 year) potential for VR/AR as a mainstream technology, so it’s been really interesting to see how the field has moved on since!

Here are some muddled thoughts!

Wireless integrated VR is a complete coup.

My office is a terrible space for VR, and also happens to be where my computer lives. I suspect this is a common enough situation. Living rooms are designed to be open and spacious, and so are easily the best place for VR. The Quest totally succeeds in moving VR to the best spaces for it, rather than expecting users to refit their houses.

VR remains an incredibly unsociable IRL activity.

The last time I got passionate about VR it was about the weird marketing for PSVR, where every poster featured “happy man in VR surrounded by laughing friends”. VR remains a terrible medium for engaging with the real world. You’re either in VR trying to ignore the real world as much as possible; or watching someone else in VR, entirely unable to share in what they’re experiencing.

I’m unaware of any popular games that exploit this dynamic in interesting ways.

The only caveat here is streaming, which is a really great feature. However, it’s weirdly hard to set up (you need to turn it on manually on the device, and if you don’t it’ll give you the world’s least helpful error message), especially on the main device where you’d want to do this on, the TV.

The controllers are GREAT, if weird.

I keep picking these up the wrong way. They work really, really well. I’ve had a few instances of the software thinking they’re positioned where they’re not, but it tends to correct itself. I have no idea what magic they use to correctly show my virtual fingers over the buttons they’re touching, but it works.

It’s still too uncomfortable.

I’ve never used a more comfortable and practical headset (although I’m sure they exist), but we’re still not even close to the goal. The strap needs awkward adjusting each time a new user wants to play, almost everyone reported some sense of nausea/headaches, it’s still a bit too heavy and just slightly annoying with glasses, it gets sweaty after a decent session (and autumn in the UK is hardly a real test of that).

The OS/built-in software is great.

The core parts of the software, such as the boundary tool, home screen, and menus are somewhere between fantastic and fine.

The interface just about passes the “can grandma play this” (we tested), which is especially important in an environment where other people aren’t able to help, being unable to see what the user is seeing (asking grandma to set up casting was beyond the scope of this test). The controllers and interface proved immediately intuitive.

The boundary tool is especially notable, somehow able to remember your last boundary. I’d love it if there was a button/action that allowed me to instantly pause the experience and turn on the headset camera, as if I’d stepped out of the boundary.

95% of the advertised experiences are rubbish.

Ok, fine, so 90% of everything is rubbish (it’s probably a LOT more, but that’s the aphorism); but there are far too many instances of the “explore” system pushing you into these, or of the software being compromised in weird ways. The Youtube app doesn’t default to VR, meaning you have to enable it for each video. The recommended browser experiences are basically all terrible. The featured videos look more like what you’d find on Dailymotion than Vimeo. Video quality is universally bad, even on the highest settings. Many featured videos are terribly filmed; the camera points the wrong way, the eyes are too close together, genres are often those that make you feel sick.

Not being able to move without feeling ill is still a serious problem.

My impression is that this is basically just accepted as a design constraint, but it’s a HECK of a constraint in a medium where natural motion is the whole point.

Thumbsticks feel unnatural and make me feel ill. Waggling my arms to move is awkward and daft. Teleporting is boring and unnatural in most experiences. Similarly, snap rotation is something you get used to. In both cases being the best bad solution doesn’t make it a good one.

Building all experiences around sitting in a static environment seems far too limiting a constraint, but the alternatives, so far, don’t strike me as the future.

It’s a fantastic toy!

Jumping into VR after some years away is a treat I expect not to experience again for a while. There’s so many wonderful totally unique experiences to try out! Video, especially, despite the universally terrible quality, has been a smorgasbord of quick and free thrills and experiences. I wish Oculus had made a free Wii Sports-style set of low-hanging fruit experiences.

There’s still no established genre(?)

There are some actual VR classics now! VR as a platform is mature to the point that games made X years ago can still be bought and played as if they were new releases; and as time goes on the number of essential VR games ticks up. VR becomes a better pitch for consumers every day.

The core problem still exists. Mobile, console, and PC have all developed a range of genres (game and otherwise) that only work because of the unique affordances of the hardware. Crucially, “genre” means something that is highly cloned and interated on, has a large, loyal playerbase, and some genre kings that can draw in that audience with each new installation. This still doesn’t exist on VR; and too many of the unique experiences can be simulated conviniently enough outside of it for most people not to bother.

This still seems basically true to me. There are absolutely some unique experiences that are well worth the entry fee; but there’s still only one Beat Saber, and the VR shooting genre (while incredibly fun) doesn’t quite feel like it has the momentum that it does on PC and console. Perhaps it’s just a matter of time and investment; and in some ways it’s refreshing that an indie developer can make something like Beat Saber without being instantly cloned and clobbered by a big publisher; but I’m slightly worried that this headset’s fate is eventually to be trappped away in the attic with the PSVR.

PS. Where the fuck is Point Blank and Time Crisis?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Building games for self actualisation

I heard an interesting challenge recently - how would you design games for self-actualisation?

I don’t have any pitches to share, but I’ve been thinking a bit about some of the traits that an experience like this might want to have - so, in no particular order:

Completeness - the activity should end with all loose ends wrapped up.

Flow - the activity should hold the player in a trance, and aim to not break their concentration

Escalation and mastery - the player might repeat an activity repeatedly, gaining confidence and mastery, to a natural crescendo

Meaningful skills and content - the player should have a sense of learning something of real value.

A sense of freedom to explore and make decisions (even if artificial)

Attraction - for players to want to engage with the game it’ll need to first attract them. It’ll almost certainly need to be beautiful, and foster curiosity, in the way a good GIF of a game makes players feel “oh yeah, I can see what I’d do here”.

Novelty - I think it’s important that players aren’t able to too easily directly compare it to something else, because it’ll enable them to fall into a familiar pattern - but at the same time making use of well known patterns is good for getting people interested and can make the early learning curve a bit less painful. This one might just be my personal preference!

Belonging and connectedness - the activity should give the player a sense of being one of many beings, and of growing closer and more in sync with them. This could involve multiplayer but I don’t think it’s a necessity (plus it’s wayyy harder)

Can you shape the experience around the pyramid of needs? The player might start blind and helpless, learn how to engage with the world, first meet other beings and grow close to them, achieve something important for/with them, and end by reaching a one-ness with the group. This could map nicely to a pacing curve/hero’s journey too, with each new stage starting out slightly intimidating, growing skilled, and completing it.

Potential References!

One Hour One Life - the way you start as an infant and grow more useful to your community

Flow/Flower/Journey - flow, progression, game feel, tone

1 note

·

View note

Text

BattleTabs ship balance

When designing ships, there are two things we look for - “is this fun and interesting?”, and “is this balanced?”. Balance is an essential part of ship design, and I wanted to share some of our process!

If you don’t know about my work on BattleTabs, then you can play it free in your browser and might be interested in reading an earlier writeup on designing the game.

“Keystone” ships

As the number of ships grows, trying to consider how a new ship compares to every other ship starts becoming an exercise in madness.

To keep comparisons manageable, we attempt to peg the effectiveness of new ships to what we call “keystone” ships.

Examples of these are the Sailboat and the Minisub. These ships are simple, reliable, and time-proven. They’re fixed points on the power curve.

One of the advantages of pegging new designs to the oldest ships is that it acts to avoid power creep in a way that would be unavoidable if all new ships were balanced against the current meta. The downside is that not all new ships feel as relevant for hardcore players.

The test for this is simple - are our keystones still considered viable additions to most fleets?

Balancing levers

When we’ve decided a ship is over or underpowered, we have 3 “levers” to play with.

Cooldowns

Cooldowns are the main lever for balancing a ship. Raising a ship’s cooldowns makes it worse, although this isn’t a linear scale!

Shorter cooldowns offer more flexibility, and are more reliable.

Longer cooldowns have a larger chance of being destroyed before it can be used.

In practice, this all means that a ship with abilities that are twice as good should have a cooldown that’s slightly less than twice as large.

Good fleet design allows for an ability to be used each turn, with no turns where several abilities are usable at once. Roughly speaking, this means cooldowns of 3-5 are typically the most useful - so should be just a tiny bit underpowered to make fleet creation a bit more interesting.

Cooldowns are an effective but blunt tool for balance, and not always granular enough to balance a ship entirely. Shape and size is a more subtle and very scalable way to fine tune balance. Ship size/shape

My initial assumption was that while bigger ships required more time to destroy, smaller ships would be harder to find, and this would roughly balance out. This turned out to be off the mark - bigger ships have a tangible advantage. Their size might be thought of as their “defence”.

Shape is important too - less standard or symmetrical shapes are harder to find - although as a minor downside, they can be harder to place in a way that doesn’t give away their shape!

Single tile ships should be avoided, because they can be frustrating to find. We recently patched in a change to the Coracle (the only 1x1) to mitigate this - it now reveals a tile on your own grid when you use a standard attack.

Our largest ship at time of writing is an 8 tiles donut. New ships could be a bit larger/harder to work out, but this risks making them tedious for the opponent to destroy, or difficult to fit on the grid.

The biggest issue with this approach is that it can’t be easily applied to ships that are already live, because tweaking art is quite expensive! Side effects

I’ve covered the universal balancing levers. The last approach is to attach further positive or negative abilities. This can help differentiate ships in interesting ways, although care should be taken not to create ships with long and complex descriptions!

here are too many of these to list, but here are some examples:

Initial cooldown - since this only affects on turn, it’s relatively subtle, while also being very tuneable (how much is the initial cooldown affected?)

Visibility - revealing a ship, or part of it, on game start/use/being hit

Neighbour effects - changing ship abilities when placed next to something else

To balance, or not to balance?

There are plenty of cases where perfect balance, as defined by “all ships should have an equal win rate” might not actually be desirable!

Gimmicks

Some ships are deliberately designed as fun gimmicks. For example - imagine a ship that entirely reveals the boards of both players. Their inclusion adds spice to the game, but they can feel cheap or undermine our design goals. We try to make these slightly less effective so that they don’t become a part of the current meta.

High and low skill ships

As a rule of thumb, ships requiring more skill should be more effective.

One of our design goals is for players to start with basic abilities and move on to those requiring higher skill as they learn to play. If skilled players can get the same win rate playing a fleet with lots of random abilities as for one requiring lots of careful thought, then they might as well stop thinking and play randomly!

We try not to let skilled players win every game though - playing fleets with lots of random abilities should still be an enjoyable strategy, and we don’t want less skilled players getting demoralised by lots of losses - or skilled players getting bored clobbering their opponents (at least, this is the theory - it seems that skilled players really enjoy winning lots)!

This might be familiar to those of you who remember the original Longboat - originally this 4 cooldown ship allowed players to keep attacking until they missed or destroyed a ship.

In our playtests this was fine, but the most skilled players could map out where their opponents were hiding in the early game and then carefully damage every ship without missing or killing any of them - potentially landing 10 hits or more!

While immensely fun, this felt a bit crushing when you were on the other side of it, so we’ve limited the ship to 5 shots - still making it one of the best ships in the game, but keeping it feeling fair for everyone.

Feedback

Despite my very best guess-timat-uition, initial ship designs are almost never balanced! There are a few ways we keep an eye on new ships.

Playtesting!

Until recently, playtesting was carried out on paper or via spreadsheet (Google Sheets being the digital swiss army knife!). This is great for saving on code time, but games typically took 5x-10x longer than they’d take if played digitally, and errors were quite common.

Nowadays we tend to take promising designs directly to a small group of testers in a special version of the game, which makes it much easier to get valuable feedback!

Some designs need several iterations before they’re ready to go live, and we’ve had a few cases of ships needing to go all the way back to the drawing board.

Community

BattleTabs is fortunate enough to have a wonderful and highly active community on Discord. One of the best ways to find out how the community votes is just to keep an eye on the conversation! BattleTabs even has a community tier list, which is fascinating for us, and always sparks interesting discussion!

Observation

My personal opinion isn’t worth all that much more than that of our more experienced players, but there’s always things you can spot from just playing the game! Are experienced players all using the same ships? What about your own strategy? Does it seem unbeatable? Are there any ships you just don’t think are ever worth playing?

What’s next?

At the time of writing we’re testing a few interesting new ships that we can’t wait to try out, and we’ve a list of literally hundreds to mull over!

Each new ship is a huge team effort that wouldn’t be possible without our incredible community.

Balancing an evolving game is a sisyphean task; but the less we need to step in and make changes, the more confident we can be that we’ve got it right.

Further reading!

If you’re interested in game balance, then I’d highly recommend Jaime Griesmer’s talks on the balance of the early Halo games. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YJ53skc-k4&ab_channel=GDC https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ikvheFiDsYY&ab_channel=GDC

I’d also recommend this seminal talk from Blizzard in 2008: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/315/Rules-of-Engagement-Blizzard-s And lastly, a take on balancing fighting games. I’d highly recommend all the design analysis on this channel! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsC8io4w1sY

0 notes

Text

Why isn't 99% of the entire housing market owned by 1% of the population?

Today's random topic is: Given the UK's long capitalist history and reliably high returns, why isn't 99% of the entire housing market owned by 1% of the population? I'm not an economist (like, at all; I make games), but it does surprise me, so I thought I'd throw some (un)educated guesses out.

This is something that's puzzled me since I started thinking about buying a house. Here in Cambridge, house prices have increased by ~2x the last 20 years, while wages have only increased ~1.75x. The same holds true in many many wealthy and up-and-coming areas in the UK and worldwide.

It's incredibly daunting for first time buyers to see the price of housing increase at a rate faster than they're likely to earn, especially the same statistic makes them clearly good things to own to secure a comfortable future. It seems obvious to me that if I was a rich, unscrupulous man, a good strategy would be to buy another house, rent it out, and use the profits to buy more houses. I've had enough landlords in my life to see that it seems to work at least fairly well; but this raises the question: Given this trend, and a few hundred years of relatively stable capitalist history, why isn't 99% of the entire housing market owned by 1% of the population? It's hard to find good statistics on this stuff, but it appears that land ownership in the UK behaves as expected, with 50% of land owned by ~<0.05 of landowners (note - not individuals, but still close enough). Profitable businesses follow this trend, and very rapidly; hence the need for anti-monopoly laws - laws which don't seem to have counterparts for housing.

So here's some possible solutions:

Houses are constantly being built Unlike land or business, houses are constantly being built, increasing supply and decreasing demand. The population is growing exponentially, which could be increasing supply faster than ownership can be transferred up the chain. That said, prices ARE rising, and it seems to me that supply isn't meeting demand. Further to that, why not just buy up (or simply build) all the newly built houses, driving prices up further? I don't know very much about this, but I'm under the impression that this IS happening, and in response there are government incentives in place to encourage first-time-buyers and extra taxes for those with several houses.

Changes to the law Laws are created and altered over time. These sometimes favour owners, but other times not, presenting opportunities for owners to sell. When all your assets are in housing, and it becomes 1% less profitable, perhaps you decide to sell some and diversify? Do the threat of new laws also create a damping effect? It seems entirely possible that anti-monopoly laws would be placed on housing if it became necessary. A key law that acts against investment in housing is Capital Gains Tax.

Family splitting On death, assets are split between heirs - perhaps ~2.5 children on average. Is it possible that this is dividing wealth around as fast as it's being amassed? There's probably some truth to this, but on the other hand we also have families merging through marriage, and trusts being created to store wealth for several individuals.

Relatively Low returns Houses seem like great investments to me, but perhaps for the ultra-wealthy the returns from an average house in Cambridgeshire don't compare to those in Dubai or from other investments that only they have access to. Perhaps owning houses is a game simply for those with an order of magnitude less wealth (the merely very-weathly), and they sell their assets to the slightly-less-but-still-very-wealthy as they transition to becoming ultra-weathy?

The stock IS most owned - by banks One possibility is that this has happened, to some degree. A good deal of homeowners are less "owners", and more "indebted to banks in the form of mortgage". This would include large owners too, who rely on banks to grow.

War! In t'olden days, the rich could lose it all if they found themselves on the wrong side of a war or similar event, and see it divided (perhaps not entirely equally, but still) between the victors. This would act as something as a damper. There's also the destruction of property angle to war. The UK hasn't had an internal war in a good few hundred years, but it seems likely that wars in other places would have had a negative impact on at least some of the super-rich? At the very least, major wars shorten the time-frame allowed for the exponential growth we're looking for.

Not enough time It might simply be that not enough time has passed! Feudalism is a few hundred years behind us, and it could simply be that the process of big-fish-eat-little-fish occurs too slowly in this market for it to have reached its zenith in the timeframe? Most people wouldn’t willingly sell the house they comfortable live in while still alive (at least, if not trading for another) so maybe the process of buying and selling is just very slow and deals with such small increments of the total market compared to other assets (like business or land) that we just need more time?

Houses are just too expensive! The UK housing stock is worth ~£8 trillion. That’s a BIG number - the same as about 10 years of the government’s tax revenue! There are some very rich folks out there, but with houses constantly being built trying to buy up the entire country’s housing stock you’d need very deep pockets. Ultimately, I think this is the biggest factor - they’re just too damned expensive for anyone to snap up, even compounded over several hundred years.

Anyway, in case it’s not clear by this point, I don’t know, nor am I qualified to make an evaluation. I am still very curious though, so if you know or can point me in the direction of someone who does, I’d love to hear about it.

0 notes

Text

Why is Connect-4 enjoyable?

I've been helping a friend with an abstract strategy game he's been working on. It's a (deep breath!) two-player-deterministic-perfect-information-zero-sum-game; and I was delighted to find that the analytical tools I've been developing for my own projects were valuable for identifying and fixing what I perceived to be design issues (many of which have been written about here in the past!). One of our discussions revolved around Connect-4; in theory, a game fitting the same abstract description (in fact, even more hardcore, since it also has no randomness).

My issue can be described as follows: The only "source of uncertainty" in the game comes from inherent complexity, which means the only thing preventing the game from being solved is how long players can be bothered to think through the effects of a given move. However, it's not complex enough to gain the interest of people who enjoy this kind of game (chess players, mathematicians). The result is that players take a long time to play their turns and are made to feel unintelligent when they lose - both terrible traits for a family game to have! However - Connect-4 is a popular game played in casual settings. What gives?

One theory is that it isn't actually popular - it's a folk game that wouldn't have much appeal if it was newly released today. There's almost certainly some truth in this, but it's clear that the game still does continue to be sold and played.

The compexity of the game fits in a sweet spot - it's complex enough not to be easily solvable, but not so complex that players don't feel capable of solving it. If, for example, the game required a bigger board and larger matches the complexity would increase, and players might be less inclined to see it as an interesting mental challenge and more as a boring and complex problem.

It’s employed as an educational game. The main audience for Noughts and Crosses (tic-tac-toe) is parents playing children. The parents feel they’re teaching their kid something valuable, and the kid feels like their parent (who keeps winning) must be performing some sort of magic trick - until they solve it for themselves! Connect-4 is a natural sequel to Naughts and Crosses, and it’s likely employed by parents for the same reasons.

My favourite reason comes from my very favourite GDC talk. One of the points made is a valuable one for strategy designers, and one I wish I'd learned the easy way - don't confuse "interesting" with "fun". Abstracts are almost always guilty of this, and I think it explains why they tend to only really appeal to people who actively enjoy "interesting" (mathematicians again being the example - although I think game designers can easily fall into this trap, especially those more interested in theory than practice - something I'm guilty of).

Connect-4 has some qualities that make it fun. Dropping colored tiles into a slot to fill a hole isn't a bad toy! It makes a nice sound! Have you ever filled up a board only to empty it again, just because you can? There's an aesthetic pleasure in creating a single line of 4, and scanning a grid that's more order than noise. It's a small thing, but I think it goes a long way.

This isn't the first breakdown of folk games I've done - you can find my previous posts on Battletabs (a commercially released Battleship variant I've been desingning) and on Minesweeper (why has a massively well known game basically fallen off the radar?). Meet me in person and I'll give you my rant (and counter-argument) on why Monopoly is awful.

And now a question for you - can you think of any other folk games that share a similar set of qualities? You might be surprised how many there are! What makes them work?

0 notes

Text

Designing BattleTabs

Hey! I’m Tom, game designer for BattleTabs!

The design for Battletabs originated from Battleship, a fairly well known board game. One of the most interesting parts of the design process has been analysing the game to find how it ticks, and pushing it in a direction that suited our goals. I thought I’d take this opportunity to share how that process went down!

When I joined the team in January the gameplay for Battletabs was just about the same as Battleships. The goal was to rework the design so that the game would have longer appeal, could be updated to stay fresh, and simply to make it more fun!

The current version of BattleTabs!

Analysis

The first thing was to break down what made Battleships fun! I played lots of different versions of Battleships and noticed a few things:

Things I liked:

The most interesting part of Battleships is when you’ve got a grid with some hits and misses and know the shapes of the enemy ships. From that information can deduce several potential positions for the enemy, which you can whittle down further with strategic play.

Some games added “combo” mechanic that I don’t believe exists in the classic game where on hitting the opponent you could play again. I quite liked this, since it meant you had a chance to take out a whole ship at once, giving a losing player a sense that they could always catch up if they had a bit of luck without feeling overpowered.

One of the advantages of Battleship is that it’s something of a folk game - most people have played it or are at least vaguely familiar with the rules (although as it turned out, not as many as I had guessed!). We could expand on the base design, but wanted to make sure it still felt like Battleships.

Most the Battleships games (especially commercial ones) I could find were identical or minor variations on the original design, which suggested there was an opportunity to expand on it to create something unique!

Things I didn’t like:

The early game isn’t very interesting. Until you’ve got some information on the board, the optimal strategy is pretty much to just take random guesses! (This is something that we’re keenly aware could be improved in the current design!)

Too much randomness! While luck is exciting, the sense (even when it’s a delusion!) that your skill at the game matters is important for a game to feel competitive and keep players happy.

Most turns are misses. In classic Battleship, the hit/miss ratio is about 0.33, and because misses don’t give the player much information the typical turn is quite unsatisfying. Obviously the player can’t hit every turn, so I was keen to find ways to make misses a little more rewarding.

Games are too similar! Although each game plays differently, opponents rarely played in dramatically different styles and the board and ship shapes are always the same.

A few versions gave special abilities to each ship, which I liked in principle but I found that in all cases they were massively overpowered and caused games to rarely last more than a few turns. In many cases the best abilities were earned by playing ads or spending money, which caused games to often feel nakedly unfair.

Update #1: “Sonar”

From this analysis I put together a list of ways we might improve the game

More interesting ship shapes would make finding spaces that might contain ships more nuanced

For similar reasons, maps could contain obstacles

A “Minesweeper” system where misses revealed the distance to the closest enemy ship would give the player more information from a miss, and also fed into the “find possible spaces for ships” gameplay

Ships with special abilities, where use of the abilities is restricted to prevent players using the same ship every turn and to prevent games devolving into blitzkriegs. Eventually we settled on a cooldown system, which can be balanced easily and provide a nice reward momentum in turn based games.

We considered lots of other ideas too, like increasing the number of ships, adding a wager system where players could bet on the likelihood of a tile containing an opponent, only allowing players to play adjacent to tiles they’d already hit, and a puzzle mode - some were discarded, others set aside for future updates!

We were keen to start improving the game immediately and incrementally, so we focused first on the “Minesweeper” concept, which solved a good number of my issues with traditional Battleships at once.

Me and Brandon tested it on paper and were pleasantly surprised to find that for once, the theory neatly panned out in reality!

Mike implemented this design and put it live not long afterwards.

Some of the many, many scraps of paper used for playtesting!

Update #2: “Fleets”

At the same time, we were thinking about ways to give the game more lasting appeal. The keys were progression, depth, and community. We wanted to build a meta-game that enabled us to reward play with valuable in game commodities, and encourage players to form stronger social bonds.

Factions

One of the ideas considered was a “factions” system (common to a few multiplayer games, including Pokemon Go), where players of a faction could lay claims to territory on a world map by winning games. We eventually decided that such an expensive system might be too risky while the game still had a relatively low playerbase.

Ships and Fleets

The idea that eventually stuck was to expand on the “special abilities” concept we’d considered previously. The idea was that players could collect new ships by winning games, and use them to create their own fleets that helped them to gain an edge over their opponents. A levelling system would be employed to provide an extra reward and help matchmake players of similar skill and fleet power.

We prototyped the concept as we had before - this time with the pandemic preventing real-life meetups, over Skype. We were pleasantly surprised how many interesting abilities we were able to think up, although to ensure we could implement and test the changes relatively quickly we decided to start with 4 predefined fleets with relatively basic ships, with the ships/XP economy as a future update.

Designing the 4 fleets

The goals for the 4 fleets we wanted to launch with were clear:

Reasonably low implementation complexity

Each fleet should have a clear and distinct role

Ships and fleets should attempt to resolve the flaws in the core Battleships design

Playtesting

Playtests went well, clearly increasing the variety and nuance of interesting situations, and making decisions over which ships to attack more interesting. One of the big advantages of the system was how easily tunable it was - if something was overpowered we could change the effectiveness of the ability, or if that wasn’t so easily possible, the cooldown.

Ship size

Something that did surprise us was how unclear the effectiveness of physically larger ships was. On one hand larger ships were easier to find, but on the other they took longer to destroy. Smaller ships only really seemed more subject to randomness, rather than “better” or “worse”, with a lucky player destroying them in one hit, but an unlucky player unable to find them.

Increasing complexity

The biggest downside was the added complexity - players would now need to read the descriptions for each ship to understand how they functioned, and select a ship each time they wanted to use an ability - low complexity relative to most competitive games, but a large step up for us. Ultimately we decided that added complexity was necessary to increase depth, and it seems likely that any solution that increased depth would have the same issue.

A new role for Sonar

In one way this update was a step back - the “sonar” update was popular and I was incredibly happy at how elegantly it resolved the “lack of skill” problem. It was an effective enough ability that we briefly considered keeping it as the default (with no ship selected) attack, but eventually decided to make it an ability in itself. As a rule of thumb, I still believe that fleets should always have one ship with some form of sonar, or at least some form of vision ability such as the new “reveal” ability, which is less interesting but also less powerful making it a useful tool for some ships!

Looking to the future!

The fleets update launched two weeks ago, and so far it’s been a success! We’ve been improving social aspects, allowing players to add friends, use emoji and invite rematches.

In the near term we’re looking at some minor design tweaks and contemplating a few new fleets, and in the longer term you can look forward to special events, progression systems, and more ships and fleets! To stay up to date, the Discord channel is the best place to get the latest news!

Thanks for reading!

Tom

0 notes

Text

I’m on sabbatical!

News! Pendragon is done, and I’ve taken two months away from Inkle; something I’ve been thinking about doing for a while now.

I’m going to keep myself busy, practicing skills and learning new ones. I’ve some freelance work to keep the cash rolling in, and some game projects to work on when I feel up for it.

Exciting times!

0 notes

Text

Knights Postmortem

Knights (the informal name for the pre-Inkle version of the game that eventually became Pendragon) was a project I started at the end of 2015 (not long after I joined Inkle) and quickly became a vehicle in which to study tactics and strategy style games.

I’d always been somewhat interested in the simplicity and tightness that often accompanies grid based games, and I thought that those qualities would also make them fairly easy to develop - turns out that part was way off the mark!

Designing an abstract strategy game

The game is still on this hard drive as “Splatoon Tiles” - it was my attempt to create a game with some features that I (naively) believed was the One True Path leading to “BETTER STRATEGY GAMES”. The philosophy has these pillars:

Perfect information (All information is visible to all players)

No output randomness (No dice rolls determining the effectiveness of an action)

Symmetrical (Both players have the same starting position and move-set)

No execution challenge (Outcome of a move isn’t based on how fast or accurately you can use the controls)

Discrete (Turn based, rather than real time; grid based rather than continuous space. Smaller numbers wherever possible!)

Minimal (harder to define, but “no dog legs” was a rule I aimed for wherever possible! You might also call it Elegance)

Keen eyed designers might recognise these elements as those typically found in the “abstract strategy” genre, including Chess, Connect-4 or Checkers.

Designing the game

Knights took about 3 years to design, in little bursts of activity; mostly around long lunches or pub trips where I’d convince Ben, Joe or Jon to playtest the game with me.

It was clear there was something interesting in the design, but also that the game had very niche appeal. I had limited success showing it to friends and family, although on rare occasion a player would share my interest. For that reason I never took my own plans of releasing the game too seriously. I shelved it many times, but never completely abandoned it at the pressing of Joe and Jon at Inkle. The design wouldn’t have made it to the finish line without them.

The simplicity of the design made rule changes typically very easy to implement, which no doubt contributed to why I kept returning to the design between other failed prototypes. We swapped out rules that made the game too easily solvable, last forever, or simply didn’t feel right. We tried a LOT of rules that didn’t stay in the design, some for a couple of games, some for years before deciding to shelve them. On reflection, something that helped was core of “claiming territory that offers movement bonuses” which never changed and helped me identify supporting mechanics.

Hard-won advice for abstract strategy designers

Games NEED at least one source of uncertainty (you can read my longer exploration of that here). The philosophy only leaves room for what I call “inherent complexity” - the game has enough complexity to make calculating the tree of outcomes for each possible move too difficult for most players. It’s more complex than Checkers, but it’s certainly not as complex as Chess

Entropy! If players can theoretically keep the game going forever, it can be very hard to break stalemates. This is especially true of games with strong defensive strategies. We fixed this by adding finite resources (collectables on the board), which had the unintended consequence of improving the pacing - a clear beginning/middle/end.

“Tight” game designs are very hard to iterate on. Changing almost any part of the design does far more than changing balance, instead altering the entire feel and set of valid strategies in the game. Adding some kind of currency token makes balance tweaks much easier; in our game that was the (very late) addition of collectables. Strategy games should aim to be fun as soon as possible. This is where having few rules can act in your advantage. A game that requires several games to learn can be enough to lose most of your audience. As well as reducing the number of rules, the two best ways to mitigate this are described below:

Tactics games should contain qualities that are “innately enjoyable”. This one is something I lucked into (or perhaps inherited from my inspirations, Splatoon and Chess-likes). There are certain aesthetic qualities that we as humans simply enjoy - perhaps as a result of biology, perhaps as a result of culture - that are essential so players can enjoy themselves without rewiring their brains. Some examples might include “capturing territory”, “collecting resources”, “moving characters”, “creating order”. I don’t have a firm handle on this, and it’s rarely analysed, but I’ve written a little more about this here.

Relatedly, rules should never feel pedantic. Because of how difficult they are to iterate on, abstracts often have rules that feel out of place but help to fix some specific issue with the design. An example is variation on the Ko rule found in many abstracts where players are prevented from getting into infinite loops by declaring the game a draw. Another might be En Passant in chess. I’m not clear why they thought adding this was a good idea, but a good rule of thumb is to try to prevent adding rules that are rarely relevant, especially if they’re not critical.

0 notes

Text

Toys in tactics games

It’s often said that before you build the game, you build the toy. Nintendo famously design and polish Mario’s movement set before they begin creating levels so that simply interacting with the game is fun.

This lens is hard to apply to turn-based-tactics games, and in most cases interacting with the game itself is tedious. Moving your army in Fire Emblem too often feels like work, especially in large levels with no obstacles blocking your way. Bumping into enemies in a roguelike is similarly not especially interesting besides watching health bars.

You can polish with nice animations and good game feel, but you're still held back by boring interactions.

For these reasons, I've been designing Spy Game with the "no-bad-turns" rule. If the toy isn't fun, then every turn should reduce busywork and should strategically interesting. And that's proven difficult to pull off!

With that said, I do think it's possible to create a good TBT toy; and many examples exist of games that, if not quite as fun as Mario, show us that something better exists.

In Checkers, capturing a piece involves jumping over them. If you can capture another piece, you have to, allowing you to chain enemies together. Both of these elements, to me, have a toy-like quality that increases my enjoyment of the game, if just a little.

Into The Breach has many moves that allow you to affect enemies with elements, manipulating them and causing event chains. Even if these actions weren't rewarded by the game, they'd be enjoyable to perform.

Hoplite's moveset provides us with this too. Sidestepping around enemies, thrusting into them, and jumping over them are innately enjoyable to some degree, in the same way that it often is in a great action game. It makes me feel cool and lets me roleplay by giving me a similar moveset to a real Hoplite.

The best examples are found in the most popular puzzle games:

Match-3 games are immensely satisfying as sets emerge and complete as the result of a single move.

In Threes moving all the pieces at once feels powerful!

Swipe-line-Match-X games (gosh this genre needs a name - Grindstone is popular with game devs at the moment) similarly give you a sense of power. Drawing lines and matching colors is fun on a very innate level.

Puyo Poyu is similar to a Match-3 on the same pleasures - set matching and propogation.

These examples have elements of what I call "inherent fun" - pattern matching, groups of 3, symmetry - low-level pleasures that are found across many of the most popular activities.

Will Wright calls them "dynamics"

As my old boss Rob pointed out to me recently, toys also make use of "inherent fun", so what's the difference between a turn-based toy and any other toy?

It's a great question.

Initially, I'd answered that in a turn-based-tactics game the rules and the toy are more tightly interwoven. To make a better toy, you need to change a rule, fundamentally changing the nature of the game.

There's truth here, and I stand by it! But isn't this basically what Nintendo do with Mario? So perhaps there isn't so much of a difference in the genre as much as there's a difference in designer mindset.

Designers of tactics and strategy games start with rules, relationships, dynamics. They think like board game designers because they know that their game lives and dies on its depth. But perhaps we've got it wrong. Perhaps instead of designing from the top down, we should start with a great toy.

0 notes

Text

Designing depth in original combat systems

I recently posted about designing games that people return to for multiple sessions, and concluded that a key factor was a sense the game might have played out very differently; ideally with a clear idea of what they could have done to improve the outcome that they can learn from for their next game.

Lack of this is, I think, at the heart of Spygame’s current design shortcomings, and helps to explain the sense of “meaningless” that I’ve identified in the current iteration of the game.

A game might achieve this sense of unfulfilled potential by leaving the player feeling of any of the following:

Could they have made fewer costly mistakes?

Mastered enemies better?

Played more efficiently?

Responded to threats faster?

Tried a different strategy?

Had better luck?

Explored more of the space?

…to name just a few!

There are a few avenues that might be applicable for Spygame, but in this article I’m going to focus on increasing the depth of the game’s combat system.

Player approaches to combat

Player solutions to a combat situation fall into one of three buckets:

Brute force

Cheese

Mastery

Brute forcing is the low skill, typically low risk/low reward option. It provides the player with a reliable but inefficient way to make progress through the game.

This is tricky for my game because I don’t have a health system, which is a common way to control the intensity of risk (losing player health) and reward (dealing enemy damage).

Ammo and positioning are common too, and could be more useful in my case. If enemies run out if ammo or need to reload, a brute force strategy is just to dodge attacks until they present an easy opportunity to attack. Good and bad positioning isn’t entirely clear in my game right now, but it probably could (and should) become moreso, if it allows you to feel like taking or giving up ground in a particular area is meaningful.

Cheese is an approach where the reward is exceptionally high for the risk taken. As such, it typically becomes the dominant strategy. If intentionally designed into a game cheese strategies can make the player feel like they’ve “broken the game”, but if poorly designed it can disincentive the player from improving.

Discovering cheese strategies is one of the most rewarding experiences a game can offer, but if it can be applied often the player will quickly tire of it, especially if such tactics are slow or uninteresting to execute.

Mastery requires players to take high risks, testing a player’s ability to recognise and exploit opportunities - sometimes also forcing them to occur.

Exercising mastery is both an implicit objective (players want to improve) and should be rewarding. In well-designed combat systems applying mastery is intrinsically enjoyable and provides extrinsic rewards in the form of in-game rewards such as extra EXP, and is the most efficient way to progress.

The skill required to master a challenge is proportional to the difficulty it presents to a player.

Note that there’s no category for high-skill/low-reward combat. I suppose it exists, but I can’t think of anywhere it might be well applied. If you’ve any thoughts, tweet me @tomkail

The problem

My combat system is entirely brute force, at its worst presenting so little risk that it feels closer to cheese. The problem is that the system rarely presents the player with exploitable opportunities, and when it does, those opportunities feel detached from the player's actions and trivial to capitalise on. The issue lies in the relationship between the turn system and the design of the move-sets.

The solution: predictably exploitable enemies

In my game, enemies change their state semi-randomly each turn, which means any opportunities can only be predictably exploited during that turn, which limits my opportunities to design them in any meaningful way.

Any opportunities (but especially those created by the player) must last long enough for them to capitalise on it.

In a real-time game this can be readily observed in a slow attack that temporarily removes the ability to block, giving the opponent the opportunity to perform a quick attack. The same is true in a turn-based game, except time is measured in turns.

Opportunities may be consistent, like “Hitting enemies on the back always kills them” or “headshots deal triple damage”. This ensures players always understand what they need to look for.

The alternative is to present bespoke opportunities that need to be learned on a case-by-case basis such as “when unbalanced, enemies can be pushed into the water” or “the ghost can only be attacked when looked at through a mirror”. These are effectively puzzles where the goal is to discover the weak spot. Using affordances like “unbalanced people are easily pushed over cliffs” can help communicate solutions, which has the bonus of being surprising and delightful. The less obvious the solution the more it becomes a puzzle for the player to work out. If this isn’t intentional, the designer needs to work on telegraphing opportunities (like the classic red glowing spot, although this is a boring example). Variety can provide puzzles and surprises, but makes the game feel less consistent, more difficult to learn, and requires much more work for opportunities to be telegraphed to the player. Additionally, fewer weaknesses make the design and development of enemy move-sets easier.

Takeaways

I could use more meaningful, communicated, non-binary variables so to give the player something non-essential to win and lose. Currently I have “turn time”, but I think I could use something more.

Enemy moves should take longer to execute, presenting opportunities for the well-positioned player to take advantage of.

Guards that kill themselves remove agency, and do there’s no sense of mastery to be had. This should probably only happen when they’re angry or very very stupid.

Pulling them off ledges is much better.

Area control should feel more significant. I should consider objectives where you need to control an area to win, death zones you need to avoid, unlit areas where your turn timer doesn’t restore, areas that affect enemy abilities, or create opportunities to kill enemies or otherwise reach objectives.

I lack mid term objectives. Something more meaningful than “kill enemy” (short term) and less than “win level” (long term); that is aided by the first and assists in the latter.

The long term objectives should be better defined!

0 notes

Text

Spy Game Retrospective + Updates

I tend to keep updates, thoughts and bugs for my longest running hobby project in a quite a while in a notepad file, but I thought I’d share my more general thoughts on it publicly, as something to look back on.

Spygame (still has no actual name) has been going for between 2 to 3 years now, depending on where I draw the line. Certainly the current repo it’s based on is 4+ years old; even if I killed the project tomorrow I’d have quite a nice little tile-based game engine to fall back on!

It’d mostly left the project idle while we geared up for Heaven’s Vault release, approaching Easter of 2019, and it was only a couple of months before Christmas when I picked it up again. I’ve been working on it quite a lot in evenings and weekends in the weeks from there to now, and I’ve gotten quite a lot done, although the more I work on it the more I appreciate quite how big and unknown this project is.

Spygame is a turn-based-tactics/action-adventure mashup. You control the spy on a turn-based hexagonal grid, and fight with goons who chase, punch and shoot at you. You have no weapons, but you can see what goons will do next as you decide your turn. A real-time turn timer keeps you from planning for too long, and runs down based on your threat level.

It’s the latest iteration of my approach to tactics design, a space I’ve been dwelling on for some time. The design resolves a few things that I consider important, but has a few blind spots that I’m increasingly becoming aware of.

Spy game is UNIQUE. I’ve never been too interested in doing things that already exist, and as far as I know, there’s not much design history in single-chararacter turn-based-tactics; and few action-adventure games where the protagonist is defenceless, and must solve problems using evasion and cunning.

It's tight and "clicky". The game is consciously designed to allow you to make moves with a single click. No inventories, no move testing or confirm menus. I want it to feel nippy, with no "bad clicks" - no turn should feel like busywork, as is all too common in popular TBT games.

It's cool! The design is originally built on a single dynamic - goons shooting at you, dodging out of the way, and bullets hitting other goons behind you. It's a little bit emergent, but tighter - I'd rather have 5 great moments repeated 20 times than 100 unique moments that don't delight. Related to this is a key pillar - always do the coolest thing.

Now - where it falls down.

Technical issues! This kind of game isn't allowed to feel technically compromised; it LOOKS too simple. It's not though, of course. There's a complex manual turn order that's a nightmare to animate - I've barely grappled with this problem and it needs resolving before it can really communicate to players. To work out the best AI moves the game does lots of board cloning and lookahead comparisons - fortunately this problem is mostly solved, but it's a good example of "invisible" tech - the kind the player doesn't care about!

Spygame doesn't have much "innate fun". Real-time games can give us avatars which feel good to control. 3D spaces are enjoyable to explore. Puzzle games satisfy an urge to pack, match and collect. Tactics games struggle with innate fun, and Spygame is no different. This is somewhat eliviated by being clicky - but getting this to where it is now was an unhill battle, creates strong restrictions on the design, and I'm still far from the goal. My hope is to fill this void with novelty, but this takes time.

There are no goals. I built my first prototype around a toy, and I've spent most of my time focused on making a sandbox that's "fine" (note that I'm immensely proud of this design - it's often remarked that Mario games are built first by making Mario fun to control, but rarely noted that "fun to control" is not the same as "a great piece of gameplay" - the goal here is simply to make something generally interesting and expressive that we can build content around, not to make it content in of itself). What I've never focused on is what the player does, explicitly or implicitly. (This has been one of the better design lessons as of late - a game has explicit objectives that are communicated to the player, such as "kill the boss" or "collect the 4 keys", and implicit objectives which emerge from the design "kill the shotgun enemy first" or "herd enemies together so you can kill them with splash damage weapons") Spygame has neither, nor do I have a route laid out to help me find them. The action-adventure genres I'm borrowing from don't help much here - these games tend to simply push the player forward, and rely on offensive combat which I explicitly don't have. The result is something that can feel a bit aimless, and ultimately a bit meaningless. I've been failing to find a general purpose solution here, and I suspect that I'll need a variety of objectives, which again takes time.

The game does do some other things, in various forms of completion, that I won't dwell on right now:

Story-driven dialogue and events, powered by ink!

Aside from combat; there's also systems affording light puzzles, stealth and platforming, that are generally proved as means of providing variety.

There's plenty more to say, but I'll wrap up there - look out for mentions of solutions for my problems as I continue to post about this one!

0 notes

Text

Play Knights!

This is a 1v1 turn-based-tactics game I designed some years back. I’ve talked about it on this blog plenty of times in the past, but never actually released it - so here it is!

https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1q1c3dCF0juYRZkcC9yLUkU2lWXR0j7L4

It’s my attempt to create an elegant, original tactics game. It took literally years, but I’m insanely proud to have cracked a game that is:

Symmetrical

Perfect information

No randomness

Easy to learn

If you’ve ever fiddled with this kind of chess-ish design, you’ll know that it’s a nefariously tricky thing to pull off without creating cracks in the design. Minimalist design of this kind can quickly afford unsatisfying stalemates, or produce dominant strategies. Trying to resolve design issues is tricky, because each iteration feels less like a rule change and far more like a completely different game, which means you need to do a lot of playtesting to test things out.

0 notes

Text

On games you come back to