Text

How vain you are to think

that you can know my heart.

Am I so cruel for hoping

that the winds of time

might not scourge away my name?

I, too, live on earth.

And all that lives dies slowly

slowly.

Grasping, then, wide-eyed,

my knife,

my key to everlasting

memory

I scratch in full awareness

my name

my “I am”

on immortality.

Your mermaids all are ghosts,

and I, to you, a wispy phantom

born into your shuttered mind.

Who are you to dare to reconstruct me?

At least my letters

rest on a living tree.

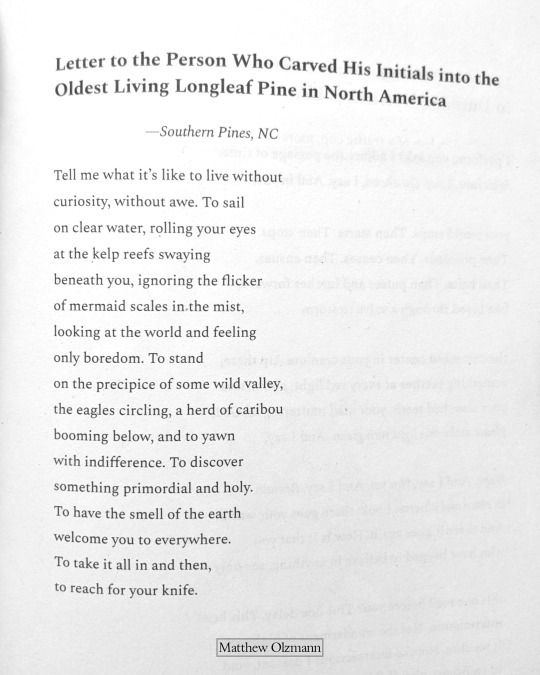

Poem for Earth Day. From Matthew Olzmann's book, Constellation Route. (Alice James Books, 2022)

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Tool

Originally written for the Parsec Ink's 2021 Sci-fi/Fantasy/Horror competition. The theme was "Habitat", and the premise was to present to the judges a surviving, thriving alternate society. The rejection letter I got from the contest was the first one I ever received! I wish I'd saved it. The story is a little rushed because I spent too much time playing Minecraft and had to pound it out within the last hours of the deadline, but I'd definitely like to come back to it sometime.

Synopsis: Hevel lives underground in a land of no funerals, where she assists her mentor Mártus in the creation of the uncanny, untiring helpers. Here, she seeks to give closure, sustain her community, and rightly name the little hole in the bottom of your skull. 1981 words.

Hevel dressed herself slowly in her waking grays: a roughspun gown and capelet, with a veil pinned over her hair. She stepped into her slippers and pulled on her soft gray gloves, rubbing her fingers on the velveted palms. Taking up her staff, she peered out the window of her small stone cell into the vast, dim cavern beyond.

The teal flame of the lighthouse pierced through the gloom like an arrowhead, making the shadows of the homes below quaver and dance. It was still bright enough to hurt her eyes, so Hevel reasoned that the sixth hour must still be young. By the time the family was due to arrive, the flame would be half-gone, and once the waking had ended, the blue fire of the seventh hour would have already been lit. That was, of course, assuming everything went right. Hevel had never led a waking before. She had assisted Mártus many times, but she’d never had to start the song or give an oration. Her mouth felt dry just thinking about it. Still, she chastised herself, there was no sense in worrying about things one couldn’t change. And besides, it was her duty, not just to the family, but to everyone underground. So, fastening her braided belt around her soft waist and checking her scroll pouch for the umpteenth time, Hevel left.

Mártus met her at the cloister door. Stooped with age, the old lizard-man stood only shoulder-height to his human protégé. But today he carried himself a little straighter, and gripping his own staff for support, he nodded to Hevel and asked, “All set?”

“All set,” the young woman replied, they departed for the fields. Mártus walked slowly and Hevel kept pace. On either side of the cobblestone path ran woven fences of cane and fungal stalk. Lanterns bobbed on sticks between the rows of grafttrees, providing the only light besides that of the distant lighthouse. Theirs was a soft, gold light, not unlike the daylight of the world above. Or so Hevel was told: she had never seen this daylight for herself.

The branches of a nearby tree rustled. It was a fast, even, continuous sound. Mártus stopped and stared into the leaves, so Hevel did too. In the lanternlight, she made out a ladder, with a helper perched at the top. It almost looked like a giant ragdoll, with a plain jutecloth head and a body covered in ribbons of plum and cream wool. With clockwork efficiency, it plucked lemons and grapefruits from the tree’s highest boughs, dropping them into its basket at a steady pace. Hevel frowned and pointed at it with her staff. “It’s coming unraveled,” she told Mártus. Around the shins and forearms, the wraps hung loose, exposing a glint of pale beneath. “Should we resew it?”

“Sure,” Mártus answered. “It’s getting to be about that time anyway. We can have it resewn with the rest of the harvesters at red-orange.” Hevel nodded. Resewing so many helpers was a time-consuming process: when she was a novice, she’d have to get up at the red flame of the first hour and sew until the indigo fire of the of the eighth had smoldered down into embers. No wakings were done at resewing time: it demanded every hand in the cloister. Hevel almost wished for that time to come as they left the helper to its work.

The family had not yet arrived when Hevel and Mártus reached the fields, but Yakhal, one of Mártus’s younger apprentices, was leaning on the gatepost. She stood up straight when she saw them and blurted out, “I thought you were the widow! Rakhum and I are finished; we just need to put in the scroll.”

“Very well,” said Mártus, opening the gate and letting the apprentices pass ahead of him. “Now, Yakhal, I have a question for you.” The young rock elf glanced back at him, her large eyes wide.

“Yes, Uncle?” she stammered.

“Where does the scroll go?” he asked.

“In the skull,” she answered quickly.

“Through where?” The lizard-man’s eyes twinkled playfully.

“Well,” Yakhal began, “it goes through the— through the, um—” She snapped her fingers as she struggled for the word. “Hevel, what’s the hole in the bottom of your skull called?”

“The foramen magnum,” said Hevel.

“The foramen magnum,” Yakhal repeated. She offered her mentor a sheepish grin, which he answered with an understanding nod. “I’ve been studying my bones really hard, Uncle,” she said, twisting her fingers into her wild, tawny hair.

“It takes time,” he replied. “I had a hard time with the names when I was your age.” The soft soil crunched beneath their feet as they walked between the rows of stone resting-boxes. The fields were dimmer than the orchard: their own lighthouse provided the only illumination. Through the teal firelight, Hevel made out the figure of her brother Rakhum a few rows down. He was bent over one of the resting-boxes, studying its contents. A few other shapes were moving in the distance, likely helpers picking crops of mushrooms.

Rakhum scarcely noticed them when they arrived. He looked up from the box, startled, and stammered out a greeting. Cut strips of soilcloth lay coiled in a basket on the ground. In another were skeins of woolen ribbon, richly dyed with fungi and lichens, along with a spool of bronze wire and a large pair of shears. While Mártus looked into the box to assess Rakhum’s handiwork, Hevel asked her brother, “So, how was it?”

“Not too bad,” he replied. “Though wiring the hands and feet did take a bit of time. I was so scared I would put them together wrong.”

“I’m sure you did fine,” said Hevel. “My first time, I accidentally switched the feet, and Mártus had to fix them for me.” Rakhum cracked a smile, the one-cornered kind their father had been known for. He mostly took after him, now that Hevel thought about it: the same brown skin and curls, the same large, nimble hands. A portrait of their father at fifteen. Plump, pale Hevel, however, was her mother’s child, with the lank black hair, dark lips and blue eyes. Hevel smiled too, thinking about them. How long had it been since their own wakings?

Mártus cleared his throat. “I redid some of the stitching along the chest, but you two otherwise did very well,” he said.

“Thank you, Uncle,” said Rakhum and Yakhal together.

“All that’s left is the scroll,” he continued. Hevel stepped up to the box.

Per the family’s request, the bones were bound in ribbons of russet and blue: favorite colors in life. They had first been reconnected with bronze wire. The skull lay uncovered on the body’s chest, its jaw held on with yet more wire. Hevel picked it up and examined it: it was light, the proportions slightly longer and more delicate than most skulls she’d seen. “Was this an elf?” she asked.

“Yes, it was,” Mártus replied.

“The bone looks very thin,” she said, turning the skull in her hands. “Look at the mandible.” She ran a finger along the underside of the jawbone, almost scared that it would crack.

“He was very sick towards the end of his life,” said Mártus. “His widow told me he could hardly move from the bed.” A slow, nostalgic smile spread across his face as he continued, “The bones of elves are like those of birds. See how long and slender the phalanges are: those are the fingers of an artist. I was told he was a skald in life: perhaps his fingers will ply the loom, now, instead of the harp.”

“Mm.” Hevel set the skull down again, then took the tiny scroll from the pouch at her hip. The night before, she’d inscribed it with a series of causal glyphs: obedience, integrity, movement. Rolling tightly in her gloved palms, she slid it into the large, round hole a few inches behind the jaw. Then the apprentices wired it to the exposed neckbones, pulled a jutecloth bag over it, and stitched it in place.

It was then that the family arrived. The young elfin widow was small and thin, practically swimming in her black mourning dress. Her seven children followed in a silent line. It had been a long time since they laid their father to rest. But the soilcloth, sown with the spores of mushrooms, had done its work. The flesh was gone, the soul was gone, and only the bones remained.

“Thank you all for being here,” said Hevel. She extended a hand to the widow, who wrapped it in her fingers and squeezed it tight.

“Thank _you,_” she replied, not meeting Hevel’s gaze. As everyone in attendance joined hands around the resting-box, Hevel cleared her throat and swallowed a few times. She closed her eyes and sought the guidance of the Great Cause, that which set in motion all things, and asked it to move her like it would the bones in the box before her. Her breathing slowed, and when she opened her eyes again, she began to speak:

“We often tell each other ‘you can’t take it with you.’ Don’t be so attached to material things, because you can’t have them when you’re gone. They go to other people, people we love.” She glanced at the face of the widow, whose lips moved silently as tears rolled down her cheeks. “When we depart, we leave behind many precious things. Things we can’t hold: memories, and love, and dreams and regrets. Things that we can, like— like—” She paused to moisten her lips. “My father was a potter. When he passed on, he left me his wheel, and his kiln, and all the little tools he used to make designs in the clay. He wanted me to continue his work.” Her eyes began to sting. “As his soul left for the world after this one, he left behind his flesh, which became the mushrooms that fed my brother and me. The last tool he left behind were— were his bones. Good bones, strong bones. Bones that helped this commune survive. What they did, I’ll never know. But I do know that the Great Cause stirred them to walk again, as it will stir the bones that lay before us now. For the soul has moved on to highest heaven, and all the earth holds now are bones.”

She began to lead them in circumambulating the box. Their hands stayed joined. Hevel sang in the language of magic, a wailing song that spoke of dark soil, and hard rock, the weaver’s shuttle, the harvester’s scythe. The miner far below in the heart of the earth, the timekeepers in the lighthouses, throwing potions in the fire. Faster and faster, they circled the box, until, with a scraping and clattering, the bones rose up and stood, awaiting command. The elfin skald was long gone: a helper now remained. So was the way of all bones.

#

When the family had gone one way and the helper another, Mártus and Hevel walked back to the cloister to prepare for the next waking. Mártus, in one of his moods, asked her, “If you could choose, what would you have your bones do when you’re gone?” Hevel thought for a few moments.

“I would want to be a harvester, I think,” she said. “The work is light, so my bones would last a long time, and I would be happy to know I’m caring for the commune even in death. What about you, Uncle?”

Mártus laughed. “Me?” he said. “I’d want to sleep.” Hevel stopped and stared at him in shock.

“Sleep?” she said.

“Sleep,” he replied. “All wrapped up in a crimson shroud, with gold on my wrists and honey-cake in my mouth. The dead used to do that, long ago. They say they still do, in the world above.”

#original fiction#fantasy#death#necromancy#skeleton#overt Thomism#creative writing#what is it with crotchety old lizard men acting as mentor figures to young women in my stories#like why is this such a recurring motif#i don't dislike it#im just surprised it happened twice

0 notes

Text

The Gray Folk

Originally written in April 2023 for the "Color Outside the Lines" contest for the children's literature zine Pine Reads Review. I'm not terribly proud of this one, and it failed to place, but an archive of only triumphs is deceitful.

Synopsis: Doggerel verses playing on the concept of the "gray man", a tactical method used to make a person inconspicuous in a crowd. Now with a vague flavor of bittersweet isolation. 365 words.

The Gray Folk

Hey, stranger.

Now you see me.

I know you know I’m here

Because you looked me in the eyes.

Are you wise to all my tricks?

Did you just see through my disguise?

Or was it just coincidence?

‘Cause I would be surprised

If you picked up that I’m one of the Gray Folk.

Hey stranger.

Now you see me.

I don’t know if you noticed

There’s no logo on my shirt.

There’s no markings on my backpack

(Save the slightest bit of dirt.)

And you might even be thinking,

“Are they trying to be covert?”

Well, good stranger, that’s the game of the Gray Folk.

Hey stranger.

Now you see me.

Our modus operandi

Is to seem like we’re not here.

We all dress in muted colors

Meant to help us disappear.

And we do it out of duty,

Or we do it out of fear.

There are many reasons you become a Gray Folk.

Hey stranger.

Now you see me.

I think some of us are running,

And then some of us are scared.

And some of us are paranoid,

And some of us prepared.

And some of us are anxious,

Or we’re socially impaired.

But we never show our hearts, no, not the Gray Folk.

Hey, stranger.

Now you see me.

We’re thieves and spies and soldiers,

Then we’re nobody at all.

We’re the silent, boring people

That you struggle to recall

When you pass us on the street

Or on the bus or in the hall.

Even Gray Folk seldom notice the Gray Folk.

Hey stranger.

Now you see me.

The way you’re looking at me

Says you’ve known this all along,

And all these years of hiding

Made my intuition strong.

Now, I could be misreading,

So I really hope I’m wrong,

Because now I think you’re one of the Gray Folk.

Hey stranger.

Now you see me.

I never thought of asking,

But what makes you act like me?

What’s the thing you’ve got inside you

That’s for no one else to see?

Is there somewhere else or someone else

That you would rather be?

What’s the thing that’s hunting you that turned you Gray Folk?

#poetry#creative writing#doggerel#gray man#less proud of this one#but happy i created#it has potential so i might come back#I wonder if I failed to place because I didn't address intersectional themes#but that's simply something that was not in my heart at the time#I cannot lie to myself#cannot be someone I am not#I am simply my heart's mouth#and it didn't feel like talking about that at the time#who am i to deceive my heart#gray

1 note

·

View note

Text

Memory Park

Originally written in November 2021 for HIST 502: Introduction to Public History.

Synopsis: Can history be neutral? How do we treat with the past? What should we do with all those old statues? Follow the groundskeeper of Memory Park, where the past stands at eye-level and the weeds are always hungry. 1227 words

The gravel crunches beneath your work boots as you make your way along the maintenance road. The pale sky hangs blue and orange-gold above you, the gathering clouds stained pink by the slow climb of the drowsy sun. Birdsong trickles out through the dense crowns of the trees. Long grass softly brushes your pantlegs. The chain-link fence that marks the edge of the service yard holds back a flood of shrubs, allowing them to thrust a few green stems through the gaps. The world in this hour feels softly hushed, and the gentle breeze carries the faint smells of crushed grass and rain. As you push through the gate in the wall of green, you’re reminded of a fact that the girl at the visitor center once shared with you.

“Did you know,” she had said, “that people in Victorian times had picnics in cemeteries? Yeah, and the kids would play there too. Public parks weren’t really a thing back then. Cemeteries were the only green spaces they had.”

You check in, fill a bucket with water, and load it onto the golf cart along with your tools. You sit down behind the wheel and take a moment to savor the cool of the morning before you start the engine. The cart jostles slightly as it rolls down a dirt path beneath the arching branches of the trees. The water in the bucket sloshes. As you roll past the EMPLOYEES ONLY sign, you make your plans for the morning.

At Memory Park, your duties as groundskeeper are relatively light. You maintain the trails and pick up garbage, but there’s little in the way of landscaping to take care of. The county’s vision for the park was of a place where nature could take its course. “Rewilding”, you think, was the term they used. You remember a message in the guestbook colorfully describing it as “a place to watch plants swallow up the statues.”

Oh, yeah. You take care of the statues too.

Not too much care. Just enough to not make a statement.

If such a thing were possible.

The dirt path leads you past the scattered statues, separated from each other by waving swaths of grass and wildflowers. Once, they may have stood on plinths, but now they rest with their feet on the ground, the same height as anybody else. Some of them have names: Forrest, Calhoun, Sherman, Junípero Serra. Others you can’t immediately recall, or had no names to begin with. Four young Confederates stand in a cluster beneath a maple tree, watching you pass with hollow eyes. One of them clutches his rifle with both hands, his head at his feet and the beginnings of a bird’s nest in the cradle of his neck. Other statues you pass stand half-cloaked in creepers, or speckled white on head and shoulders from bird droppings. These you do not clear away. Nature is taking its course.

Someone has spray-painted the word “MURDERER” onto the chest of an equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson. You stop the cart, get down, and inspect it. His eyes have been X-ed out in similar fashion, and various obscenities are painted on the sides of his horse. (What did the horse ever do?) Each stroke of red spray-paint seems to throb with the painter’s anger. There was vengeance in this gesture.

Nothing some soap and water can’t fix. You grab your bucket and sponge the paint away, as per protocol. The water runs red from between the fingers of your sponge-hand and pools at Jackson’s feet. You leave him to dry in the sun: there’s a lot more park left to cover.

In the southeast section, you pick up the remains of a picnic left beneath a chasteberry tree.

In the southwest section, you pause at the edge of the pond to watch a heron fish.

In the northwest section, you come across a statue in the middle of a clearing. At the feet of the nameless Texas Ranger blooms a crop of American flags and red-white-and-blue pinwheels. A Beanie Baby rests in the crook of his arm as he reaches for his Walker Colt. You stand for a moment, watching the pinwheels turn and the flags flutter in the breeze. Pride and patriotism bubble up from the ground in this place.

After quickly glancing around, you gather up the items and place them in the back of the cart, as per protocol. The tiny yellow blooms they had hidden peep through the grass. The flags and pinwheels are still in good condition, and it seems a waste to throw them out. You consider donating them to the local daycare.

You spend a little more time on your rounds, picking up the odd bit of trash, as well as a sticker-covered Hydroflask for the lost-and-found. You take a short break at the northern edge of the park. Rolling hills stretch before you, the paintbox dripples and brushstrokes of summer wildflowers breaking up the waving expanse of green. Some rumors had been going around about expanding the park, and you imagine bronze soldiers and marble missionaries gazing at the hazy blue mountains beyond.

The last stop on your rounds is the front gate, which you unlock and push creakingly open before returning to your cart. You unpack a sack breakfast and a thermos of coffee. The wind pushes flocks of fattened clouds across the blue field of the sky, and you watch them for a while, your eyes watering slightly from the intensity of the color.

A slight rustling to your left draws your attention. You take another drink of coffee, then get up from your seat to investigate.

In the middle of a stand of trees, a man in shorts and a gray hiking jacket kneels at the base of a statue of Jefferson Davis. He’s taking a charcoal rubbing of the nameplate at the base. After a moment, he gets up and waves to you. “Are you the groundskeeper here?” he asks.

“Yep, that’s me,” you reply.

“I just wanted to thank you for what you’re doing,” says the man. He’s fair-skinned, with big, guileless blue eyes and a full, neatly trimmed brown beard. “Like, preserving all this stuff? That’s important. I mean, I’m no Confederate or anything but… this is history.”

“It sure is,” you reply. The man turns around and puts his hands on his hips to survey the grove.

“This is a good place,” he continues. “Lotta nature here. You know, I read on the Internet somewhere that it takes 40,000 years for a bronze statue to break down.”

“Is that right?”

“Mm-hmm.” He turns to face you, then glances back over his shoulder and adds, “’Let us cross over the river and rest in the shade of the trees.’”

You do not respond.

The man gives you a cheerful wave and starts to leave. You get closer to the statue and look at it for a little while. Your eyes are at the same level as Davis’s. The man has left his charcoal stick at the base, and you consider throwing it away as you pick it up.

Instead, you call after the man, “Hey, you forgot your charcoal,” and he thanks you as he takes it back.

You sit down at the base of the largest tree and linger for a while in the shade.

#short story#history#public history#original work#original fiction#creative writing#realistic fiction#statue#confederate monument#what did the horse ever do?#memory#Szoborpark#second person

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Nickel For the Lizardman

Tucson Festival of Books 2023 unsolicited writing sample

Synopsis: When the circus comes to town, eight-year-old Edie Cartwright goes to see the "ferocious, fearsome Lizardman" in his grotty old tent at the edge of the fairgrounds. But posters don't always tell the truth, and sometimes you need to open your ears for the full story. 1453 words

ONE DAY ONLY!

the poster declared.

FROM THE HIGHEST CAVES OF SHANGRI-LA

THE FEARSOME

FEROCIOUS

LIZARDMAN!

Two yellow eyes glowered down at me below the words. Well! That sounded worth my fifty cents. I followed the posters to the far end of the fairgrounds. A lady in a polka-dot suit was waiting for me by the entrance of a grubby yellow tent. She started as I approached, like she was shocked I came all this way. The lady looked left to right, like there was another attraction I had meant to see instead. I handed her my nickels.

“You got five minutes, missie,” she said with a toothpaste-ad smile. “Don’t worry! He doesn’t bite.” I thanked her and stepped inside. The air was thick and sticky, with a sour, moldy smell that stuck to your tongue and made your eyes water. The sun beat down on the top of the tent, throwing a sickly yellow light over everything inside. Four steps from the entrance stood a big iron cage with straw and torn-up newspaper strewed along the bottom. And right in the middle was a big dark lump, like a forgotten sack of laundry.

“H-hello?” I asked as I took a step forward. The musty air seemed to swallow my words. I stood an arm’s length from the cage, my heart fit to bust out of my chest.

With an almighty snort, the lump reared up and threw its bulk against the bars. The cage pitched forward and then settled back with a thump, throwing up a cloud of dust that choked me as I screamed. I fell flat on my rear and sat there, panting, choking, panting, choking. If I could speak, I would have cussed.

The Lizardman hissed. He glowered between the bars with cunning black eyes, gripping the iron with ten curved amber claws. Mottled scaly brown skin hung off his lanky bent-up body, and his frontside was shocking blue. His long tail lashed like a snake. From deep inside, he gave a low, rumbling alligator bellow and hissed between his teeth. And then, after a moment or two, he asked, “Scared?”

I sat stunned. And then, slowly, I nodded. That seemed to please the Lizardman, and he let go of the bars to sit back on his haunches, arms crossed. “Well, I hope this was worth it for you, little girl,” he said. “You could have bought ten bags of popcorn or ridden the elephant twice for the amount you paid to be here.”

“You talk,” I said. I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“Of course I do,” he replied. “I’m the Lizardman.” I nodded again. “Oh, and close your mouth,” he added. “You’ll let the flies in.”

I closed my mouth.

I sat on the ground for what felt like a small eternity. I said nothing. Neither did the Lizardman. I felt like I’d been called on in class and didn’t know the answer. “What’s your name?” I said at last.

“I don’t have one,” the Lizardman replied.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Why don’t you have any hair?” I felt my face heat up.

“My mama shaved it off on account of lice,” I sputtered.

“Ah,” said the Lizardman. He laced his fingers under his chin and closed his eyes.

“It was mean of you to ask about my hair,” I told him.

“It was mean of you to ask about my name,” he responded. “I don’t have one. No one thought to give me one.”

“Why is that?”

“You really ought to think before you speak.” We lapsed into silence again.

After chewing on my thoughts for a moment, I said, “I’m sorry I made you upset, Mr. Lizardman.” He took his time before answering.

“Mm. It’s all right. I wouldn’t have expected you to know.” Silence fell again.

“My name’s Edie Cartwright,” I offered.

“Charmed,” the Lizardman said. He closed his eyes again. As I spent a little more time thinking, he said, “Go tell the woman outside that the Lizardman wants to do his special trick.”

“‘Special trick’?” I asked.

“You’ll see.”

I let the lady know. She followed me in, lit the Lizardman a big cigar, and stepped outside again. I watched the Lizardman take a pull and blow a plume of smoke straight up into the air.

“That’s not much of a trick,” I said.

“No, it’s not,” he agreed, “but it’s the only way they let me have these.” He took another pull and blew smoke out his nostrils, like a dragon.

“So,” I asked, “do you ever miss Shangri-La?” He gave me a sidelong glance.

“Shangri-La?” he said. “Ah. The posters. Shangri-La doesn’t exist, Edie. I’m from Delaware.”

“Are you really?”

“Mm-hmm. Worcester County, specifically. At least, that’s what I was told. I was sold to the circus as an egg.”

“Oh,” I said. “I’m really sorry to hear that.”

“Don’t be. It’s actually not a bad life.” He chuckled and tapped the ash from his cigar. “You know, I used to be under the Big Top. I juggled knives on the tightrope and sang opera with the clowns. The magician used to have a trick where the clowns would wrestle me into a cabinet and spin it around. Then he’d pop out like he’d been changed by magic.”

“Wow!” I cried. “That would have been a sight to see! But how come you’re not under the Big Top anymore?”

“I’m past my prime,” said the Lizardman with a shrug. “My joints are stiff, my bones all ache, and I don’t see quite so well anymore. But Lizardmen don’t grow on trees, so they kept me around. I was in the sideshow for a while, until I took a bite out of the human blockhead for saying something stupid. But this little tent suits me fine. It’s warm and dark, and nobody comes around.”

The tip of a thin pink tongue passed over the Lizardman’s lips. “And the nice thing about that is,” he continued, “you don’t overhear the gossip. You know. Whether Sadie loves Chester or Alfonso, or if the fire-eater’s a communist. Or whether the Lizardman’s worth the chickens they feed him.” He chewed on the end of his cigar and stared off into space.

I got to my feet and brushed the dirt off my skirt. “I think you’re worth all the chickens in the world,” I said.

“Really?” said the Lizardman.

“Really. There’s got to be a million or more chickens in the whole United States of America, but how many Lizardmen are there?”

“I couldn’t tell you,” the Lizardman replied. “I’ve never seen another one of my kind.”

“Never?” I asked, eyes wide.

“Never,” said the Lizardman. He tapped a little ash from his cigar.

“Well,” I said, “even if there was a whole Lizard New York, you’re the only one who sings and juggles and smokes a cigar. There won’t never be another Lizardman like you in the whole history of the world.”

“Don’t use double negatives, Edie.”

“Don’t sell yourself short!” My voice nearly cracked. “And if you want me to, I’ll come back here every single year. I’ll save up all my quarters so I can come here and sit on the floor and listen to you tell your stories. I’ll listen to you. I’ll listen to you.”

The Lizardman slowly lowered his cigar. “I think I’d like that, Edie Cartwright,” he said. I dug into my pockets for my last nickel and stepped up to the cage.

“For you,” I said, showing it to him. “To remember me by.”

The Lizardman slipped a bony hand between the bars of the cage. I dropped the nickel in his palm, and he pulled it back again. He turned the coin over in his hand, again and again. It flashed like a minnow in the dim.

“Time’s up,” the lady in the polka-dot suit softly said as she poked her head into the tent. The Lizardman closed his hand.

“Don’t forget,” he whispered.

“I won’t,” I whispered back. “This time next year. The circus always comes around.” The Lizardman nodded and raised a solemn hand goodbye as the lady led me out of the tent.

I walked home that evening, wrote the date on a scrap of paper, and hid it under my pillow. Mama scolded me for how dirty I’d gotten, but I barely even heard her. I was already thinking about next year. I was ready to wait.

And I’ve been waiting since. It’s been forty long years, and the circus has never missed a date. But the lady in the polka-dot suit sells lemonade now, and there’s a flea circus in the old yellow tent.

#short story#original work#magical realism#circus#lizardman#lizard person#shangri la doesnt exist edie#original fiction#fiction writing#creative writing

4 notes

·

View notes