Text

Top 10 Games of 2019

This was an extremely good year for games. I don’t know if I played as many that will stick with me as I did last year, but the ones on the bottom half of this list in particular constitute some of my favorite games of the decade, and probably all-time. If I’ve got a gaming-related resolution for next year, it’s to put my playtime into supporting even smaller indie devs. My absolute favorite experiences in games this year came from seemingly out of nowhere games from teams I’ve previously never heard of before. That said, there are some big games coming up in spring I doubt I’ll be able to keep myself away from. Some quick notes/shoutouts before I get started:

-The game I put maybe the most time into this year was Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn. I finally made the plunge into neverending FF MMO content, and I’m as happy as I am overwhelmed. This was a big year for the game, between the release of the Shadowbringers expansion and the Nier: Automata raid, and it very well may have made it onto my list if I had managed to actually get to any of it. At the time of this writing, though, I’ve only just finished 2015’s Heavensward, so I’ve got...a long way to go.

-One quick shoutout to the Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney Trilogy that came out on Switch this year, a remaster of some DS classics I never played. An absolutely delightful visual novel series that I fell in love with throughout this year.

-I originally included a couple games currently in early access that I’ve enjoyed immensely. I removed them not because of arbitrary rules about what technically “came out” this year, but just to make room for some other games I liked, out of the assumption that I’ll still love these games in their 1.0 formats when they’re released next year to include them on my 2020 list. So shoutout to Hades, probably the best rogue-like/lite/whatever I’ve ever played, and Spin Rhythm XD, which reignited my love for rhythm games.

-Disco Elysium isn’t on this list, because I’ve played about an hour of it and haven’t yet been hooked by it. But I’ve heard enough about it to be convinced that it is 1000% a game for me and something I need to get to immediately. They shouted out Marx and Engels at the Game Awards! They look so cool! I want to be their friend! And hopefully, a few weeks from now, I’ll desperately want to redact this list to squeeze this game somewhere in here.

Alright, he’s the actual list:

10. Amid Evil

The 90’s FPS renaissance continues! As opposed to last year’s Dusk, a game I adored, this one takes its cues less from Quake and more from Heretic/Hexen, placing a greater emphasis on melee combat and magic-fuelled projectiles than more traditional weapons. Also, rather than that game’s intentionally ugly aesthetic, this one opts for graphics that at times feel lush, detailed, and pretty, while still probably mostly fitting the description of lo-fi. In fact, they just added RTX to the game, something I’m extremely curious to check out. This game continued to fuel my excitement about the possibilities of embracing out-of-style gameplay mechanics to discover new and fresh possibilities from a genre I’ve never been able to stop yearning for more of.

9. Ape Out

If this were a “coolest games” list, Ape Out would win it, easily. It’s a simple game whose mechanics don’t particularly evolve throughout the course of its handful of hours, but it leaves a hell of an impression with its minimalist cut-out graphics, stylish title cards, and percussive soundtrack. Smashing guards into each other and walls and causing them to shoot each other in a mad-dash for the exit is a fun as hell take on Hotline Miami-esque top down hyper violence, even if it’s a thin enough concept that it starts to feel a bit old before the end of the game.

8. Fire Emblem: Three Houses

I had a lot of problems with this game, probably most stemming from just how damn long it is - I still haven’t finished my first, and likely only, playthrough. This length seems to have motivated the developers to make battles more simple and easy, and to be fair, I would get frustrated if I were getting stuck on individual battles if I couldn’t stop thinking about how much longer I have to go, but as it is, I’ve just found them to be mostly boring. This is particularly problematic for a game that seems to require you to play through it at least...three times to really get the full picture? I couldn’t help but admire everything this game got right, though, and that mostly comes down to building a massive cast of extremely well realized and likable characters whose complex relationships with each other and with the structures they pledge loyalty to fuels harrowing drama once the plot really sets into motion. There’s a reason no other game inspired such a deluge of memes and fan fiction and art into my Twitter feed this year. It’s an impressive feat to convince every player they’ve unquestionably picked the right house and defend their problem children till the bitter end. After the success of this game, I’d love to see what this team can do next with a narrower focus and a bigger budget.

7. Resident Evil 2

It’s been a long time since I played the original Resident Evil 2, but I still consider it to be one of my favorite games of all time. I was highly skeptical of this remake at first, holding my stubborn ground that changing the fixed camera to a RE4-style behind the back perspective would turn this game more into an action game and less of a survival horror game where feeling a lack of control is part of the experience. I was pleasantly surprised to find how much they were able to modernize this game while maintaining its original feel and atmosphere. The fumbly, drifting aim-down sights effectively sell the feeling of being a rookie scared out of your wits. Being chased by Mr. X is wildly anxiety-inducing. But even more surprisingly, perhaps the greatest upgrade this game received was its map, which does you the generous service of actually marking down automatically where puzzles and items are, which rooms you’ve yet to enter, which ones you’ve searched entirely, and which ones still have more to discover. Arguably, this disrupts the feeling of being lost in a labyrinthine space that the original inspired, but in practice, it’s a remarkably satisfying and addicting video game system to engage with.

6. Judgment

No big surprise here - Ryu ga Gotoku put out another Yakuza-style game set in Kamurocho, and once again, it’s sitting somewhere on my top 10. This time, they finally put Kazuma Kiryu’s story to bed and focused on a new protagonist, down on his luck lawyer-turned-detective Takayuki Yagami. The new direction doesn’t always pay off - the added mechanics of following and chasing suspects gets a bit tedious. The game makes up for it, though, by absolutely nailing a fun, engrossing J-Drama of a plot entirely divorced from the Yakuza lore. The narrative takes several head-spinning turns through its several dozen hours, and they all feel earned, with a fresh sense of focus. The side stories in this one do even more to make you feel connected to the community of Kamurocho by befriending people from across the neighborhood. I’d love to see this team take even bigger swings in the future - and from what I’ve seen from Yakuza 7, that seems exactly like what they’re doing - but even if this game shares maybe a bit too much DNA with its predecessors, it’s hard to complain when the writing and acting are this enjoyable.

5. Control

Control feels like the kind of game that almost never gets made anymore. It’s a AAA game that isn’t connected to any larger franchises and doesn’t demand your attention for longer than a dozen hours. It doesn’t shoehorn needless RPG or MMO mechanics into its third-person action game formula to hold your attention. It introduces a wildly clever idea, tells a concise story with it, and then its over. And there’s something so refreshing about all of that. The setting of The Oldest House has a lot to do with it. I think it stands toe-to-toe with Rapture or Black Mesa as an instantly iconic game world. Its aesthetic blend of paranormal horror and banal government bureaucracy gripped my inner X-Files fan instantly, and kept him satisfied not only with its central characters and mystery but with a generous bounty of redacted documents full of worldbuilding both spine-tingling and hilarious. More will undoubtedly come from this game, in the form of DLC and possibly even more, with the way it ties itself into other Remedy universes, and as much as I expect I will love it, the refreshing experience this base game offered me likely can’t be beat.

4. Anodyne 2

I awaited Sean Han Tani and Marina Kittaka’s new game more anxiously than almost any game that came out this year, despite never having played the first one, exclusively on my love for last year’s singular All Our Asias and the promise that this game would greatly expand on that one’s Saturn/PS1-esque early 3D graphics and personal, heartfelt storytelling. Not only was I not disappointed, I was regularly pleasantly surprised by the depth of narrative and themes the game navigates. This game takes the ‘legendary hero’ tropes of a Zelda game and flips them to tell a story about the importance of community and taking care of loved ones over duty to governments or organizations. The dungeons that similarly reflect a Link to the Past-era Zelda game reduce the maps to bite-sized, funny, clever designs that ask you to internalize unique mechanics that result in affecting conclusions. Plus, it’s gorgeously idiosyncratic in its blend of 3D and 2D environments and its pretty but off-kilter score. It’s hard to believe something this full and well realized came from two people.

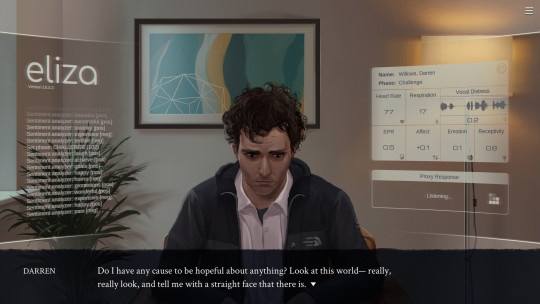

3. Eliza

Eliza is a work of dystopian fiction so closely resembling the state of the world in 2019 it’s hard to even want to call it sci-fi. As a proxy for the Eliza app, you speak the words of an AI therapist that offers meager, generic suggestions as a catch-all for desperate people facing any number of the nightmares of our time. The first session you get is a man reckoning with the state the world is in - we’ve only got a few more years left to save ourselves from impending climate crisis, destructive development is rendering cities unlivable for anyone but the super-rich, and the people who hold all the power are just making it all worse. The only thing you offer to him is to use a meditation app and take some medication. It doesn’t take long for you to realize that this whole structure is much less about helping struggling people and more about mining personal data.

There’s much more to this story than the grim state of mental health under late capitalism, though. It’s revealed that Evelyn, the character you play as, has a much closer history with Eliza than initially evident. Throughout the game, she’ll reacquaint herself with old coworkers, including her two former bosses who have recently split and run different companies over their differing frightening visions for the future. The game offers a biting critique of the kind of tech company optimism that brings rich, eccentric men to believe they can solve the world’s problems within the hyper-capitalist structure they’ve thrived under, and how quickly this mindset gives way to techno-fascism. There’s also Evelyn’s former team member, Nora, who has quit the tech world in favor of being a DJ “activist,” and her current lead Rae, a compassionate person who genuinely believes in the power of Eliza to better people’s lives. The writing does an excellent job of justifying everyone’s points of view and highlighting the limits of their ideology without simplifying their sense of morality.

Why this game works so well isn’t just its willingness to stare in the face of uncomfortably relevant subject matter, but its ultimately empathetic message. It offers no simple solutions to the world’s problems, but also avoids falling into utter despair. Instead, it places measured but inspiring faith in the power of making small, meaningful impacts on the people around you, and simply trying to put some good into your world. It’s a game both terrifying and comforting in its frank conclusions.

2. Death Stranding

For a game as willfully dumb as this one often is - that, for example, insists on giving all of its characters with self-explanatory names long monologues about how they got that name - Death Stranding was one of the most thought provoking games I’ve played in a while. Outside of its indulgent, awkwardly paced narrative, the game offers plenty of reflection on the impact the internet has had on our lives. As Sam Porter Bridges, you’re hiking across a post-apocalyptic America, reconnecting isolated cities by delivering supplies, building infrastructure, and, probably most importantly, connecting them to the Chiral Network, an internet of sorts constructed of supernatural material of nebulous origin. Through this structure, the game offers surprisingly insightful commentary about the necessity for communication, cooperation, and genuine love and care within a community.

The lonely world you’re tasked to explore, and the way you’re given blips of encouragement within the solitude through the structures and “likes” you give and receive through the game’s asynchronous multiplayer system, offers some striking parallels for those of us particularly “online” people who feel simultaneous desperation for human contact and aversion to social pressures. I’ve heard the themes of this game described as “incoherent” due to the way it seems to view the internet both as a powerful tool to connect people and a means by which people become isolated and alienated, but are both of these statements not completely true to reality? The game simplifies some of its conclusions - Kojima seems particularly ignorant of America’s deep structural inequities and abuses that lead to a culture of isolation and alienation. And yet, the questions it asks are provocative enough that they compelled me to keep thinking about them far longer than the answers it offers.

Beyond the surprisingly rich thematic content, this game is mostly just a joy to play. Death Stranding builds kinetic drama out of the typically rote parts of games. Moving from point A to point B has become an increasingly tedious chore in the majority of AAA open world games, but this is a game built almost entirely out of moving from point A to point B, and it makes it thrilling. The simple act of walking down a hill while trying to balance a heavy load on your back and avoiding rocks and other obstacles fulfills the promise of the term ‘walking simulator’ in a far more interesting way than most games given that descriptor. The game consistently doles out new ways to navigate terrain, which peaked for me about two thirds of the way through the game when, after spending hours setting up a network of zip lines, a delivery offered me the opportunity to utilize the entire thing in a wildly satisfying journey from one end of the map to another. It was the gaming moment of the year.

1. Outer Wilds

The first time the sun exploded in my Outer Wilds playthrough, I was probably about to die anyway. I had fallen through a black hole, and had yet to figure out how to recover from that, so I was drifting listlessly through space with diminishing oxygen as the synths started to pick up and I watched the sun fall in on itself and then expand throughout the solar system as my vision went went. The moment gave me chills, not because I wasn’t already doomed anyway, but because I couldn’t help but think about my neighbors that I had left behind to explore space. I hadn’t known that mere minutes after I left the atmosphere the solar system would be obliterated, but I was at least able to watch as it happened. They probably had no idea what happened. Suddenly their lives and their planet and everything they had known were just...gone. And then I woke up, with the campfire burning in front of me, and everyone looking just as I had left it. And I became obsessed with figuring out how to stop that from happening again.

What surprised me is that every time the sun exploded, it never failed to produce those chills I felt the first time. This game is masterful in its art, sound, and music design that manages to produce feelings so intense from an aesthetic so quaint. Tracking down fellow explorers by following the sound of their harmonica or acoustic guitar. Exploring space in a rickety vessel held together by wood and tape. Translating logs of conversations of an ancient alien race and finding the subject matter of discussion to be about small interpersonal drama as often as it is revelatory secrets of the universe. All of the potentially twee aspects of the game are balanced out by an innate sense of danger and terror that comes from exploring space and strange worlds alone. At times, the game dips into pure horror, making other aspects of the presentation all the more charming by comparison. And then there’s the clockwork machinations of the 22-minute loop you explore within, rewarding exploration and experimentation with reveals that make you feel like a genius for figuring out the puzzle at the same time that you’re stunned by the divulgence of a new piece of information.

The last few hours of the game contained a couple puzzles so obfuscated that I had to consult a guide, which admittedly lessened the impact of those reveals, but it all led to one of the most equally devastating and satisfying endings I’ve experienced in a video game recently. I really can’t say enough good things about this game. It’s not only my favorite game this year, but easily one of my favorite games of the decade, and really, of all-time, when it comes down to it.

#outer wilds#death stranding#eliza#anodyne 2#control#judgment#resident evil 2#fire emblem: three houses#Ape Out#Amid Evil#games#video games#GOTY

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video Game Year in Review: The Top 10

As with any year-end list, this one probably isn’t complete. Last year, I fell in love with Nioh over winter break after I had already made my top 10, and just a few days ago, I started playing Hollow Knight. As I made clear in my previous lists, Metroidvanias can be hit or miss for me. I can get fed up with wandering around without a clear destination, and Hollow Knight has a bit of that so far, but it also has one of the most atmospherically welcoming settings for a video game in recent memory, and so far I’ve been pretty damn enraptured by it. I’m not too worried about it making the list at this point; it didn’t even technically come out this year anyway, but its Switch release earlier this year gave it somewhat of a second debut, for all the earned attention it finally got. At least I got a little shout-out here before publishing.

Anyway, here’s ten games I loved the shit out of in 2018. This was one year with a handful of games that I absolutely adored, none of which necessarily immediately jumped out to me as hands down the best one of the bunch, and honestly, that’s the way I’d prefer it, but it did make ranking them a bit tough. Really, from number five onward, the ranking gets pretty interchangeable. I didn’t plan on the game in my number one spot being the one that it is until I actually wrote out my feelings for it and decided that out of all them it was the easiest for me to just gush about. Alright, no further ado:

10. Donut County - Overall, it’s probably a good thing that Donut County isn’t longer than it is, but for as mechanically simple as sucking objects into an ever-expanding void is, it’s something that I felt I would’ve been perfectly entertained doing for a lot longer than the game lasted. Donut County has a wildly inspired and novel central gameplay hook, a relatably goofy sense of humor that might border on obnoxious if it weren’t so sincerely delivered, and an anti-gentrification, anti-capitalist message that mostly works without beating you over the head too hard with it. Ben Esposito and his team have created one of the most charming and original games I’ve played in years here.

9. Paratopic - “Cinematic” is a grossly overused and frequently inappropriate word to use in games criticism, but this game often had me coming back to the word, observing how many ways it feels like it authentically takes inspiration from creative methods seen more often in film, particularly art films, than in games, much more so than say, Red Dead Redemption 2, which typically embarrassingly pales in comparison to any movies it’s obviously aping from. There’s its willingness to not explain to you what’s going on, letting you pick up on clues from scenery and incidental dialogue. Its multiple switching perspectives, laced together to draw meaningful narrative connections. Its tendency to sit in the atmosphere of a scene. Its ability to tell a succinct story intended to be experienced in one sitting. And most of all, those jump cuts. I know Paratopic isn’t the first game to employ this technique, but as far as I can remember, it’s the first that I’ve played to utilize them for purposeful artistic effect, and every time it happened, it was oddly thrilling. I loved when I’d switch from walking to suddenly driving, and had a moment of panic, as if I suddenly just woke up at the wheel. The cliffhangers scenes would occasionally end on made me desperate to get back to that thread. Hell, even just the fact that there clearly were scenes, that lasted a few minutes at a time, then moved on to the next one, felt weirdly refreshing at a time when AAA design is becoming so absurdly bloated. Paratopic excited me, not in its desire to emulate a separate art medium, but in its casual realization of how many underutilized narrative techniques work genuinely effectively in this medium.

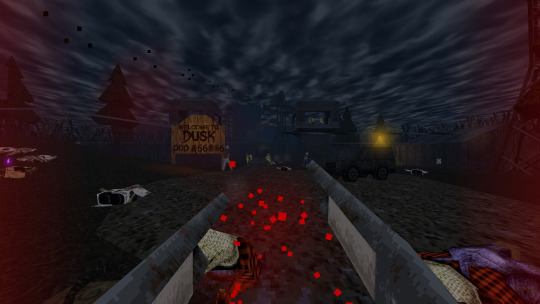

8. Dusk - I really can’t imagine a game that more perfectly matches my Platonic ideal of “video game comfort food” than Dusk, aside from, maybe, the game in the number one spot of this list. I was raised on 90’s PC FPS games like Doom and, as is much more relevant to this game, Quake. Yeah, for the most part, it’s nice that games have moved on, both in depth of gameplay and artistry, but goddamn does a back-to-basics twitchy shooter with inspired level design and creepy atmosphere just feel good sometimes. The grainy, chunky polygons of this game encapsulate everything I love about the rudimentary but remarkably evocative minimalism of early 3D graphics. The movement feels absurdly fast by modern standards, and the effect is thrilling - every projectile is dodgeable, as long as your reflexes are sharp enough. Undoubtedly the most impressive thing about this game is its ambitious level design, so much of which rivals even John Romero’s. The longer this game goes on, the more sprawling and labyrinthine it becomes. The map shapes become increasingly wacky. The gothic architecture becomes more foreboding and awe-inspiring. Dusk does a lot with a little, and in the process, makes so much more than a tribute to game design and aesthetics of the past - for me, it stands right alongside its obvious inspirations as one of the very best of its ilk.

7. Into the Breach - An absolute masterclass of game design. Into the Breach leaves nothing about its mechanics obscured, making sure you understand how every move is going to go down just as well as it does, and the fact that the result is still compellingly challenging is a sure sign we’re in the hands of remarkably skilled and intelligent developers. The narrative in this game is sparse - you assume the role of time-looping soldiers attempting over and over again to save your world from alien invasion (think Edge of Tomorrow), and that’s pretty much all you get for the plot, aside from some effective but minimal character beats and dialogue one-liners. And yet, every battlefield, a small grid with its own arrangement of sprites (giant creepy-crawlies, various creative mech classes, structures full of terrified denizens given a modicum of hope at the arrival of their ragged potential saviors) offers a playground for drama to unfold, as gripping and epic as any great mecha anime battle. As I mentioned in my previous list with Dead Cells, I have trouble sticking with run-based games, and this game wasn’t quite an exception - honestly, if it had something resembling a more traditional narrative campaign, I could see it potentially filling my number one spot. But that a game of its style nevertheless stuck with me as well as it did proves what a tremendous achievement I found it to be.

6. Astro Bot Rescue Mission - This was both the first game I’ve played fully in VR and the first game I’ve ever platinumed. I guess that might say something about how thoroughly I fell for it. For some reason, one of the questions that my brain kept posing while playing this game is, “would you like this game as much if it weren’t in VR?” I would like to pose that first off, if this wasn’t a VR game, it would be quite a different game, but yes, probably a perfectly delightful 3D platformer in its own right. But most of all, this game helped me realize what a bullshit question that is in the first place. By virtue of its VR nature, this game is just fundamentally different, just as the jump from 2D to 3D resulted in games that were just fundamentally different. The perspective you’re given watching over your little robot playable character allows to look in 360 degrees, and often you need to, if you’re seeking out every level’s secrets, and yet, while it moves forward, it doesn’t follow you vertically, so sometimes you’re looking up or down as well. It’s difficult to describe exactly how this perspective is so much more than a gimmick or something, outside of the cliched exaggeration of “it feels like you’re really there, man,” but honestly, this statement isn’t wrong. I truly did feel immersed in these levels in a way that I wouldn’t have if this weren’t a VR game, and while it’s not exactly a feeling I now desire from every game, it does stand out as one of the singular gaming experiences I had in 2018 as a result.

5. Thonebreaker: The Witcher Tales - I gushed plenty about this game in my review. How its approach to Gwent-based combat is both welcoming to newcomers and remarkably varied, offering new ways to approach and think about the game with nearly every encounter. How its sizable story is filled with fascinating characters and genuinely distressing choices, forcing you to grapple with the inherent injustices of your position. How its vivid art style and wonderfully moody Marcin Przybyłowicz score sell The Witcher feel of this game, despite how differently it plays from the mainline entries of the game. And maybe most of all, how criminally overlooked this game has been. So I’ll make the same claim I did before - if The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt did something for you, it’s likely this game will too. Don’t worry about the card game - I did too, and trust me, it’s fun. It’s the new Witcher game; that really ought to be all you need to know.

4. Yakuza 6: The Song of Life - There’s...a lot about the Yakuza games that I’ve come to adore, but one of the biggest ones that kept sticking out to me while playing The Song of Life is how they build a sense of place. After playing Yakuza 0, set in 1988, and Yakuza Kiwami, set in 2005, I played this one, set in 2016. Each time, same Kiryu, but older, same Kamurocho, but era appropriate. Setting every Yakuza game in the same map has to be one of the quietly boldest experiments in video games, forgoing fresh new vistas to explore in favor of the same familiar boulevards, alleys, and parks of the iconic red-light district, painting an exquisitely detailed and loving portrait of a neighborhood changing with the decades. While Kiryu’s exasperation at once again walking into the all-too-familiar crowded streets of Kamurocho, brighter and louder than ever, hardly matched my eagerness to see how it had changed, it felt appropriate. Though he’s still the hottest dad (grandpa?) in town, he is kinda old now, and he’s certainly earned the right to just be over it a little. Even the silliest of the era-relevant sub stories (one of which delightfully features Kiryu putting a selfie-stick wielding, obnoxious-stunt pulling, wanna-be influencer shithead in his place) serve to underscore how out of place he now is in his old stomping grounds.

By contrast, the other setting of Yakuza 6, the quaint seaside town of Onomichi, very quickly begins to feel like an idyllic retirement destination. The introduction to this part of the game has to be my favorite video game moment of 2018 - Kiryu trying to calm a hungry baby, while walking the deserted streets after dark in search of one store that still happens to be open. The faint sound of ocean in the distance effectively evokes the freshness, the bitterness, of the air. The emptiness and darkness of the space is almost shocking, compared to the sensory overload of Kamurocho. And there’s Haruto. Kiryu took Haruka in when she was 9, so he’s never had to deal with a baby before. He’s out of his element, but hardly unwilling. The help he gets from Kiyomi and his other new friends is the kind of comfort Kiryu needs at this point in his life. Likewise, the events in Onomichi play out like a retirement fantasy - building an amateur baseball team out of local talent, building relationships with the denizens of a bar in an incredible Japanese version of Cheers, hanging out with the town’s Yakuza, who are so small potatoes they seem to barely fit the definitions of organized or crime. It all works beautifully as a touching send-off to my favorite video game character.

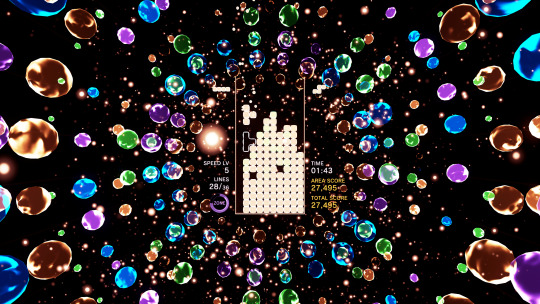

3. Tetris Effect - There was a long time where I was contemplating putting this as my number one game. I went through some strange conflicts in the consideration - next to all these original, thoughtful games, am I really going to say that fucking Tetris is best one of them? Is that even fair? Is this game really anything more than just regular-ass Tetris but with some pretty lights and sounds and a 90’s rave kinda vibe? The answer to all of these, is, of course, yes, but also no. I’d defend my choice any day, though. This is the first game to actually get me into Tetris. I always appreciated it; it’s a classic, but it was never a game I had actually put much time or thought into before. This game not only sold me on Tetris, but got me obsessed with it, to the point where the name feels remarkably appropriate: ever since I began playing, I’ve been seeing tetriminos falling - in my sleep, in daydreams, any time I see any type of blocky shape in real life I’m fitting them together in my mind. The idea that all Tetris pieces, despite their differences, need each other and complement each other and can all fit together in perfect harmony, and that this is a metaphor for humanity, has to be some of the cheesiest bullshit I’ve ever heard, and yet, the game fully sold me on it from the first damn level. It’s all connected. We’re all together in this life. Don’t you forget it.

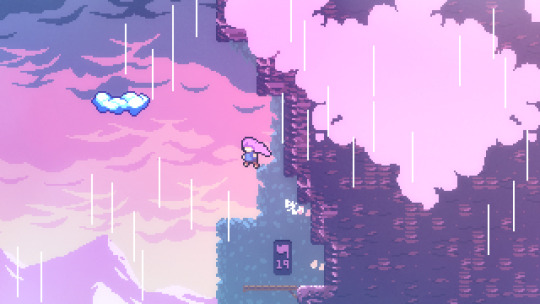

2. Celeste - This is a damn near perfect game, both as refreshing and demanding as a climb up a beautiful but treacherous mountain ought to be. I died many, many times (2424, to be exact), but the game explicitly encouraged me to be proud of that, acting as a friendly little cheerleader in between deaths, assuring me that I could do it. It’s both a welcome break from the smug, sneering attitude so many “difficult” games tend to traffic in, and absolutely central to its themes involving mental health. As the shockingly good plot starts making it increasingly clear that it’s about Madeline’s quest to conquer (or, at least, understand) her inner demons, the gameplay itself offers a simple but effective metaphor for struggling with mental illness - yes, it’s hard, and yes, you’re going to suffer and struggle, but you can make it, and you will make it, because you’re so much better than you think you are. Oh, and also, it’s not all bad, because at least you get to listen to some absolutely rippin’ tunes while you do it.

1. Ni No Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom - (Another one I reviewed!) This is my ideal JRPG. In my mind it stands next to childhood treasures like Final Fantasy IX. Unlike some recent Square projects that specifically try to clone their late 90’s output, this game hardly feels beholden to the game design of the past, and yet, feels of a piece with that era in a respectably non-cloying way. It has a bright, colorful, inviting world full of charming characters, an all-time great soundtrack by Joe Hisaishi, and an exciting, deep combat system with an emphasis on action. Building my kingdom of Evermore was remarkably satisfying, down to all the little dumb tasks my citizens would ask of me, none of which my very good boy King Evan was too busy or too proud to refuse. There’s very little grinding. It’s a long game by most standards, but at 40-something hours, it feels lean by JRPG standards. And for as much of a storybook fantasy as the plot is, as much as it reduces woefully complicated socio-political issues into neat, resolvable tasks for Evan to solve, it always came across as perfectly genuine, and sometimes surprisingly affecting. It’s the game that I’ve wanted to play since the PS1 Final Fantasy games stole my heart as a kid. That’s hardly what I expected it to be as I started into it, and what a joy it was to discover that it was.

#Ni No Kuni#Ni No Kuni II#Ni No Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom#Celeste#Tetris#Tetris Effect#Yakuza 6: The Song of Life#Yakuza#Yakuza 6#Thronebreaker#Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales#The Witcher#Astro Bot#Astro Bot Rescue Mission#Into the Breach#Dusk#Paratopic#Donut County#Review#List#Game of the Year#GOTY#Top 10#game#Games#video game#video games#criticism

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video Game Year in Review: Honorable Mentions

When I compiled the list of games I played this year that didn’t make it to my top 10, and weren’t remasters, remakes, or re-releases (see previous list), the number came out to just over 10, with the few over the 10 spot either just not being particularly remarkable (Splatoon 2: Octo Expansion) or games that I put so little actual time into that I really didn’t get the chance to form coherent thoughts about them (Prey: Mooncrash and BattleTech, both examples of types of games I want to resolve to not be so afraid of playing in 2019).

So the remaining 10 that I did want to mention are an interesting bunch. Not all of them are games that I loved. A decent amount of them are games I had serious issues with. But they all had something to them, something that made those issues that I had all the more frustrating, because it prevented me from dismissing them outright. My feelings about these games are varied enough that I wanted to rank them, so I suppose this list could just be called “Reese’s Top 20 games of 2018: 20-11,” or, “The Problem Children,” or something, but “Honorable Mentions” works fine for me.

10. The Messenger - Though I have never played Ninja Gaiden, and therefore don’t really have any nostalgia for the type of game this dual-8-bit/16-bit/action-platformer/Metroidvania was clearly going for, the early parts were executed pretty damn well. Tight controls, great music, some very fun and memorable boss fights, gameplay that was challenging but not, I imagine, anywhere near as rage-inducingly challenging as the games it was based on. Those initial four or five hours or so felt enjoyable and complete enough that the fact that I fell off pretty soon after the game pulls a very significant aesthetic and gameplay shakeup not enough to make me hate the game. As cool as a concept as it is to literally jump back and forth between different eras of game design, the “Metroidvania” part of this game was filled with the shit that tends to frustrate me about that style of game - aimless wandering and tedious backtracking. A very interesting experiment that, for me, didn’t quite pay off, but the effort produced a pretty unique game.

9. Iconoclasts - As far as its gameplay goes, this game is almost the inverse of The Messenger’s brand of Metroidvania, highlighting all the things that I actually can love about the genre. Sure there’s backtracking, but the layout of the levels is thoughtful and inspired enough that it rarely feels tedious: I often found myself very excited to gain my new ability and revisit a previous area because - just like the best Metroid games - I know exactly where I can use it, have been wondering about it for a while, and can finally see what’s on the other side. What ended up bogging down the experience of this game for me was the surprising emphasis on story and long-winded dialogue scenes. While I definitely really liked a handful of characters, the game’s increasing willingness throughout its run-time to put verbose speeches in all of their mouths wore a bit thin, given how thoroughly okay the general plot was. Still, game has some of the absolute most gorgeous pixel animation I’ve ever seen.

8. Monster Hunter World - As it seemed to be for many, the streamlined (though still irritatingly idiosyncratic) systems management, lush world and creature design, and conveniently slow part of the year that it released all made this the first Monster Hunter game I was willing to fully commit to. For a while, the game really won me over - experimenting with weapons was deeply satisfying, and the care and evocative detail in the designs felt inspired and compelling. I even played a bit of multiplayer with friends, and had a lot of fun with it, despite how generally committed I tend to be to single player experiences. After a while, though, I stopped being wowed by the animations and controls to start to be bothered by how careless the game seemed to be about its colonial fantasy, what a generally destructive force you and your team are on this beautiful world. It’s not as though this isn’t something that was obvious from the beginning, it’s just that for a while there, I figured it must actually be going somewhere with it, that there must be some commentary it was building toward. What I was met with was disappointing silence, and LOTS of grinding.

7. Red Dead Redemption 2 - I felt a lot of ways about this game, some of which I managed to capture in the review I wrote a couple months ago. There’s so much about this game that I hold against it and Rockstar, both surrounding it (the abusive culture of crunch in its development, their lack of care in getting an indigenous and/or black actor to play Charles) and within the game itself (the stretching of a decent story to an absurd length, controls so clunky they often broke the role-playing the rest of the game was so good at encouraging). But the things that I loved about this game - the stunningly atmospheric world, the complicated and nuanced character dynamics in the camp, the ways in which it allows one to experience and engage with its details - all stuck with me as well. This game represents so much of both what I want games to be going forward and what I never want them to be again.

6. Minit - Weird as it sounds, as much as I liked this game, my main gripe with it was the primary mechanic around which it was based. I loved the minimalist black-and-white art style: the way the white lines shined on my HDR TV is an excellent example of how “simple” graphical styles can take advantage of modern technology as well as any graphically demanding powerhouse. The world was a joy to explore, a miniature Zelda with a unique sense of humor. I honestly just never got why I was only allowed to enjoy it a minute at a time. The game seemed to do little to justify its central hook, and most of the time it ended up feeling more like a hindrance than a meaningful game changer. Nevertheless, Minit gave me a short, sweet experience that stuck with me more than I expected it to.

5. God of War - Having never really liked the previous games in this series, I went into this one with fairly low expectations, despite the near-universal praise it was getting. The story really didn’t do much for me. The father/son dynamic was fine, but hardly the innovative step forward in video game narratives many seemed to claim it was. Kratos is still an inherently ridiculous character, no matter how much depth they try to give him in this game, though I did thoroughly enjoy Christopher Judge’s performance. The real hook of this game, outside of its very pretty visuals, is its really just superb combat. They nearly entirely did away with the hacking and slashing of the previous games, and created a deliberate, thrilling system of combat juggling. There are a decent amount of moves at your disposal, but it never feels like an overwhelming amount, and the balancing act you can achieve in utilizing all of them properly results in just some of the most satisfying combat I’ve ever experienced in a game.

4. All Our Asias - This was the first of several lo-fi 3D polygonal games I played this year - the others will show up in my top 10 - and I’m just so excited about the coming wave of game developers inspired by 90’s PS1-era aesthetics, an era I’m personally much more nostalgic for than the still-prevailing 16-bit pixel art of many indie games. This is probably also the weirdest of that style of game that I played this year (and given what one of the others is, that’s saying something), an essay in video game format, an exploration of the bizarre nature of memory, told through abstract shapes and landscapes. Creator Sean Han Tani tells a wonderfully personal story here about racial identity and complicated family relationships, by navigating the conceptual framework of your player character’s father. It’s a singular experience that I still think about often, nearly a year after playing it.

3. Mario + Rabbids: Kingdom Battle - Donkey Kong Adventure - I’ll admit that my time with Mario + Rabbids: Kingdom Battle last year was my first real dip into tactics gaming, an experience that allowed me to gingerly step my foot into some deeper water this year (some of which I discovered was still too deep for me, like BattleTech). But for as easy as the first half of that game was, I maintain that the back half was surprisingly challenging. This year’s DLC, Donkey Kong Adventure, is not challenging. Donkey Kong is so overpowered it feels like it must have been a mistake, and the way that he can combine attacks with other characters is just ridiculous. But, weirdly enough, that’s part of what I enjoyed about this addition, a fairly breezy few-hour adventure where the most fun comes from seeing just how badly you can fuck some Rabbids up in a single move. Having Donkey Kong grab an enemy, throw him at another enemy, hit both plus a nearby enemy his banana boomerang, then having Rabbid Cranky charge into all three of them and blast them with his shotgun-esque Boombow never really gets old, at least for the well paced 8 or 9 hours that the game lasts.

2. Dead Cells - An endless, side-scrolling action platformer with tight-as-hell, ultra satisfying combat, beautiful art design, AND it was made by team of French socialists with no bosses who all get paid the same? I mean, fuck yeah. Dead Cells, a game that I originally played a bit in Early Access last year, and enjoyed so much that I decided to wait until the official release before truly delving into it, is a game that largely plays like the dream it sounds like on paper. I’m not sure if I’ve ever played at 2D game with combat as good. Generally, I’m not huge on run-based games, and did hit some walls in this game where I just felt like my own ineptitude was getting in the way of my enjoyment, and the game wasn’t giving me much between runs to make me feel like I was actually making any progress. I still haven’t actually beat it, but it’s become my default palate cleanser game that I play a few rounds of in between other games or while listening to podcasts or music, so I’m still plucking away at it. I’ll get there someday.

1. Return of the Obra Dinn - I enjoyed this game so, so much, even if sometimes more on a theoretical level than a practical one. The style is impeccable - I really will never get tired of the brief tease of opaque, incidental dialogue or sound, followed by the sudden explorable tableau of death(s), soundtracked by haunting strings. The gameplay is inspired - I’ve had few gaming experiences in recent memory as fulfilling as any time the little music que popped up after I solved a death, confirming that I had gotten three deductions correct. I have to admit, though, that those moments were spread further out than I would have wished. Part of this is just happenstance - I didn’t realize until quite a few hours into this game that by zooming in on someone, you’ll match them to their picture, something that would have undoubtedly saved me a lot of frustrating time in which I was grappling with trying to figure out whose fuzzy faces were whose. Nevertheless, I felt like I was too often given too little information, and had to take guesses between one of a few possible suspects, many of which were informed by racial assumptions that made me actively uncomfortable. This was, no doubt, part of the point, so it’s hard for me to hold it against the game, but it regardless did lead to a pretty exasperated final couple hours of play. Despite these complaints, its hard for me to think of this game as anything other than a wildly successful achievement - innovative, inspired, both intelligently designed and remarkably trusting in its player’s intelligence. Maybe a little too trusting, in my case.

#Return of the Obra Dinn#Dead Cells#Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle Donkey Kong Adventure#All Our Asias#God of War#minit#Red Dead Redemption 2#Monster Hunter World#Iconoclasts#The Messenger#video games#games#review#gameoftheyear#podcast#criticism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Video Game Year in Review: Remakes, Remasters, and Re-releases

I’ve never made a list of remakes, remasters, and re-releases before, but then again, I don’t think I’ve ever played so many in a single year to even be able to. 2018 was a particularly busy year in this end of video game releases, nearly exclusively due to the Nintendo Switch. Now in its second year, the Switch may have been light on brand new first party titles, but the rush of seemingly every developer to get new and old games alike on the portable console came into full swing. “When’s that game coming to Switch?” has turned into a question that could be reasonably applied to...just about every game, but perhaps no more so than great Nintendo games originally released on their previous, unsuccessful console, the Wii U. These games enjoyed a second life in 2018, with many, including myself, playing 2014 games that we never got to as if they’re brand new. Switch re-releases don’t account for every game on this list, but they are a very clear majority...

5. Bayonetta (Switch remaster) - This is the one game on this list that I actually didn’t like. But I tried. Like it’s spiritual cousin, Devil May Cry, Bayonetta is a game that makes you feel shitty for not being good at it. I consistently got low grades on my combat performance, but didn’t feel like the game was offering any particularly helpful guidance in how to improve. It just kept pushing me forward, with dwindling currency, supplies, and patience, all the while just being a bit of a dick to me. If I found gameplay to be more fun, maybe I also would have been more willing to be entertained by its puerile, edgy aesthetic, but as it was, that just became another thing to grate on my nerves. If there’s one thing I gained from this game, it’s the assurance that not every popular game from the late 2000’s that I missed out on while I was barely playing video games is worth catching up on.

4. Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze (Switch re-release) - The Donkey Kong Country games have always eluded me. I never had a SNES, so I couldn’t quite get into the bizarre proto-3D graphics of the originals once I finally checked them out. Tropical Freeze is the game that finally proved to me why people love these games so much. Donkey Kong is an unusual platforming star - his hulking frame gives him a slightly out of control momentum that is off putting until it’s suddenly satisfying, and that moment within the first couple hours of play where how to control him suddenly clicked was the start of two weeks of compulsively playing this game to completion during my summer break.

3. Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker (Switch re-release) - What a unique game. A puzzle platformer whose main mechanic sometimes feels like your player character’s lack of an ability to jump. With a perfectly minimalistic mobility design ethos, this delightful experiment encourages you to explore the little 3D dioramas that make up its levels to completion. I’ve been obsessively mining each of them for all they’ve got before moving on to the next one, and it’s slow going - I’ve still probably got about ⅔ left of the game to go. But the thought of it is actually making look forward to my upcoming, otherwise painfully long flight to Japan, because absorbing myself in this seems like the perfect way to make hours go by without notice.

2. Dark Souls: Remastered - Before this remaster, I had played brief moments of the original Dark Souls on a friend’s PS3. Really, though, Bloodborne is where I fell in love with Souls-style games, and last year I obsessed over the excellent, overlooked Nioh. Finally coming to this game after more recent games in its style was a mixed experience for me. Obviously, the rather plain, blocky textures of the last generation are already aging quickly, but the game still has enough style and atmosphere that I wasn’t particularly bothered by that aspect of it. The combat, however, felt...bland. I know, I know, this game and its predecessor, Demon’s Souls, are praised for revolutionizing action RPG combat, with their tight controls and deliberate moves. If it weren’t for this game, the combat I love in Bloodborne and Nioh wouldn’t exist. But having put so many dozens of hours into Nioh, a game with combo attack strings and multiple stances, made the switch back to a game where each weapon basically only has two attacks, feel just kinda elementary. Not easy, mind you - despite my experience with this style, I still found this game to be welcomingly challenging, but performing the same moves over and over again just wore thin.

Nevertheless, this game has something that no game inspired by it has quite been able to replicate, or even, seemingly, really tried to, and that’s the incredible, interlocking level design. Yeah, Dark Souls 3 and especially Bloodborne obviously pull some similar magic tricks in connecting separate sections together, but regardless, feel like fairly linear games. Firelink Shrine in this game has three separate directions you can head in to start with, and the paths just keep branching from there. This game puts remarkable trust in the player in her ability and desire to explore, experiment, and undoubtedly die many times before finding the path of least resistance (because even that path offers plenty of resistance). This is the aspect of Dark Souls that kept me going. Not only has it not aged a day, it’s almost even more impressive in retrospect, a lightning-in-a-bottle kind of flash of creative genius.

1. Yakuza Kiwami 2 - Last year’s Yakuza 0 was my first Yakuza game, and this year’s Yakuza Kiwami 2 was my fourth. As you might have guessed, I’ve fallen very, very hard for this series. For those not familiar, Kiwami 2 is a remake of Yakuza 2, originally on PS2, just as last year’s Yakuza Kiwami was a remake of the original game. While that game used 0’s engine, which was made for PS3 originally, Kiwami 2 uses the brand new, very pretty engine used for Yakuza 6: The Song of Life, which was released earlier this year. This game recreates just about everything in the original game, and adds a hell of a lot more. This feels so much like a brand new game to me that I considered just putting in on my main top 10, and honestly, the reason that I didn’t had less to do with the fear of breaking any non-existent rules about what qualifies for a year-end list, and more to do with the fact that The Song of Life was already on there, and I just wanted more space to talk about how much I love the shit out of Yakuza.

This game improves on Kiwami in just about every aspect. The main story is a lot more compelling, and it’s obvious that Yakuza 2 is tonally where this series really came into its own, with its so-serious-it’s-actually-kinda-funny Japanese gangster soap opera, mixed with deliberately silly as hell sub stories. In particular, there are two very deep and expansive side stories built around mini-games added to this game: the cabaret club management game borrowed and modified from 0 and the Majima construction clan battles borrowed and modified from The Song of Life. While I appreciated these in those respective games, something about the execution in this game just got me absolutely obsessed. Kiryu’s roll that he fits into with the misfit hostesses of the cabaret club and their scrappy underdog story is my happy place. The older professional wrestlers that play the mumbly, grumpy businessmen/fighters in the clan battle mini-game led to a couple of scenes that had me gleefully cackling out loud. Starting this game out, I had arguably already spent more than enough time playing Yakuza games over the last couple years, but it’s a testament to just how endearing this game is that after 40 or so hours of play, if Kiwami 3 were to suddenly be surprise announced and released, I would have been happy to jump straight into it.

#Yakuza#Yakuza Kiwami 2#Yakuza Kiwami#Yakuza 0#Yakuza 6: The Song of Life#Dark Souls#Dark Souls: Remastered#Bloodborne#Nioh#Dark Souls III#Captain Toad#Toad#Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker#Switch#Nintendo#Nintendo Switch#PS4#Sony#From Software#Donkey Kong Country#Donkey Kong#Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze#Bayonetta#Bayonetta 2#Devil May Cry#video games#criticism#podcast#review#list

0 notes

Text

Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales is so much more than a Gwent-based spin-off

I put about 150 hours into The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. It’s probably my favorite game ever. I tend to think that I’ve more or less done everything in that game that there was to do, but there is one glaring exception to that: Gwent. I tried a couple rounds of the collectible card game in the beginning of the game, didn’t quite understand what was going on, and certainly didn’t care to learn when the rest of the game offered a big, beautiful world to explore, full of great stories created with near unparalleled writing. I had never really gotten in to card games within video games in general, really - I remember reacting to Final Fantasy VIII’s Triple Triad in much the same way. And I’ve certainly never attempted Hearthstone, or any such similar DCCG’s. This is all to say, I’m still a bit surprised at how thoroughly I fell in love with Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales, a game built largely around Gwent.

CD Projekt Red’s newest game was released just a few weeks ago to disappointingly little fanfare. What reviews there are have been pretty strong, but let’s be real - this is an isometric RPG with visual novel elements whose combat is based around a card game, and it was released three days before Red Dead Redemption 2. It’s a shame, though, because the game really does offer so much to those who, like me, might be unsure about undertaking such an experience. It’s got a gorgeous, comic-book-esque art style that makes exploring the game’s detailed maps a joy. It’s very well written, with novelistic prose and strong characters delivered by Jakub Szamalek, one of the writers from The Witcher 3. Marcin Przybylowicz returns with another memorable and moody Polish-folk-music-inflected score. While combat is entirely based around Gwent, the rest of this game is devoted to exploring detailed maps and making hard, morally ambiguous decisions in the main story. In other words, the team behind The Witcher 3 made a brand new, full, deep RPG set in the universe of The Witcher, and you really should be paying attention.

Thronebreaker is a prequel-ish spin-off, set just before the events of the first Witcher game. It centers around Meve, Queen of Lyria and Rivia, and her quest to reclaim her land from a devastating Nilfgaardian invasion. The morally gray nature of The Witcher universe is an even more ever-present central tenet in this game than previous ones, as it deals explicitly with the inherent injustice of monarchical governance. Meve is, as queens go, a very good one. She’s brave, determined, and compassionate, willing to fight to the death for the good of her people. But war nevertheless makes for hard decisions, especially when you’re leading a small army with limited resources against a giant imperial machine, and attempting to navigate the complex politics of multiple lands.

The maps you explore in this game can include big cities and castles, but for the most part, you’re traversing through rural lands, passing by small villages and farms, grappling with the cruelty of feudalism. The peasants you meet have next to nothing to begin with, so often are they forced by the government you rule to give up their earnings, at least in part so that you can live in luxury. Now that war has come around, it only gets worse for them - you physically take resources from them for your army, and often conscript them to join. You stick your nose into local conflicts you don’t fully understand or appreciate. Mass inequality and injustice are everywhere, and try as you might to be a just and fair monarch, you can only go so far when your existence is one of the primary reasons for that mass inequality and injustice.

There are rarely “good” options to choose from in this game. A decision always involves a compromise, and no matter what, somebody is going to be made very unhappy by it - most likely including you. There are often more ostensibly righteous or noble options, but the consequences of those can sometimes have an effect that makes you wish you had chosen the other one. “You’ve chosen one evil over another” is a prompt that you get very used to popping up - it’s the game’s sole response to you making a story-altering decision. Sometimes this can feel pretty damn off. Sorry, game, but choosing not to kill a messenger when I’ve just been reminded of the rules of war, or saving an elf from a mob of racist humans attempting a public execution are just not evils, no matter how you look at them. The point of it is showing how your actions, even seemingly altruistic ones, have consequences, and the shades of gray thing works pretty well for the most part, but despite the game’s assurance to the contrary, not every choice you make is an evil one.

The more successful decision making comes when you really feel those consequences, either through a hit to your resources, or a bit of writing that explains what ended up happening. There’s a heavy dollop of Machiavellianism to these decisions, as it often comes down to choosing between what’s right and what’s successful. You need gold, people, and resources to survive. In the early parts of the game, you’re pretty desperate for all three of these things. So when you stumble across an already disturbed grave that has valuables in it, do you pillage it? You want to say no, and yet, you weigh the options - the only negative would be upsetting company morale, but morale is already high after saving a church graveyard from a monster, so pushing it down to normal isn’t a great loss in comparison to leaving behind gold. In that same section, you can chase down a group of bandits that stole gold from the church. After you retrieve it, you can either return it, or keep it for yourself. I returned it, but I didn’t feel quite as great about it as I expected to. Sure, I made a small group of nuns happy, but does this truly benefit the kingdom as a whole if we’re short on money to fight our enemies?

That’s not to say that the game encourages you to make the selfish choice. I’ve heard it claimed before that the Witcher games reward policies of non-interference and cynicism in the face of injustice, but I don’t think that’s necessarily true. Sure, taking the gold for myself would have made the game a little bit easier for me, but that’s temptation, not reward. There’s always a cost for getting involved, but it’s hard for me to see that as the game punishing me. There are consequences no matter what, and this is the rare game with a semblance of a morality system that often makes attempts at doing the right thing the most narratively interesting choice rather than the choice with the most practical reward. This becomes clear in the second chapter, where, after seeing the atrocities wrought by the opposition, you can’t help but become more willing to recognize the cruelty in yourself, to make decisions you never figured you’d make. This wouldn’t feel nearly as impactful if you didn’t start out trying to make Meve the most just ruler possible.

Though the game presents a complex world of bitter division and desperate cynicism, and thus engaging with it leaves little possibility of not getting blood on your hands, the writing rarely feels ignorant of the roots of injustice. The human lands that you spend most of the game exploring are deeply racist. The Elder Races - elves and dwarves, mostly, have been subject to countless pogroms across these lands, and even when they aren’t being straight up murdered, are never treated as equals to their human neighbors. So the fact that the Scoia’tael, a radical group of nonhuman guerillas, exist isn’t surprising, nor can you not have sympathy for their alliance with the invading Nilfgaard. Though the Nilfgaardians can be seen as a stand-in for any massive imperial force, from the Roman Empire to Nazi Germany, with all the delusions of racial superiority that tend to go with empire, their invasion of the Northern Kingdoms actually does seem to make life a bit easier for nonhumans - one of the chief complaints of the humans you meet living under occupation is how many more rights have been granted to elves and dwarves.

The Scoia’tael, fighting for Nilfgaard, thus become another enemy you must face. Some of them, justifiably thrilled at the prospect of overthrowing their oppressors, use the destruction of a kingdom like Aedirn as an opportunity to slaughter whole villages of humans as revenge. You see the mindless violence they’ve committed, then are faced with the threat of it yourself, and there’s really no other choice but to take the Scoia’tael down. It feels terrible. Every aspect of it. And I believe the game earns this trudge through moral quicksand. It recognizes the righteousness of the Scoia’tael, even as it forces you into opposition against them. It’s both awful, and a surprising relief from the social commentary video games so often fall into - the reductive and mischaracterizing Bethesda/Rockstar/Bioshock “both sides suck” approach. It recognizes the power differences at the root of the issue, and doesn’t hide from the ugliness that ensues.

That’s not to say that the writing is always perfect when dealing with this stuff. Cut a single corner with material this volatile and you can end up with a pretty off-putting scene, as Thronebreaker occasionally does. There’s one character, a human named Black Rayla, that joins your team in the second chapter. She’s a seasoned fighter of the Scoia’tel, and thoroughly racist as a result, and yet, she’s useful to your cause, so you allow her in. This is all well and good, and theoretically should make for some interesting internal conflicts, but there were several scenes where I was disturbed by Meve’s lack of response to Rayla’s nationalist bullshit. There was one scene where she was going down some real “I don’t have a problem with them, as long as they know their place” garbage, and I just decided to dismiss her at that point. I wonder what would happen if she stayed with my group till the end, if Meve would have more to say to her after she wasn’t quite as desperate for her help. I’d hope so, but considering the lack of mindful writing around her character I witnessed it, I wouldn’t exactly expect it.

For as fascinating as the narrative of this game is, the thing you’ll probably spend the majority of the game doing is playing Gwent, and for a solid two-thirds of my time with the card combat, that was something I was very happy to be doing. The system built for this game, similar to, but modified from its Witcher 3 iteration, is deep, strategic, and occasionally pretty challenging. It feels made for newcomers like myself, mostly unfamiliar with Gwent, or even the standard mechanics shared by most card games, in the way that it eases the player into it. The first hour or so of the game is the official tutorial, but really the whole first chapter feels like a fairly natural extended tutorial for beginners, starting you off with a fairly limited deck in order to solidify the basics. For the most part this is very well done, though there were some particular aspects of the game that didn’t seem to be entirely explained, and took me a pretty long time to pick up on exactly how they worked.

The biggest strength that the card game here boasts is real variety. So many of the battles have particular rules or cards in play that drastically change the way you have to approach your strategy. Many of these come in the form of “puzzles” - aptly titled special battles where you’re given a specific set of cards and there’s really only one solution that you have to deduce through experimentation and logic. These are largely fantastic, not only because they’re all unique and fun in their own right, but because they often serve as mini-lessons in how individual units work and the various strategic ways they can be utilized.

Then there are the standard battles, where you actually get to shuffle and draw your own deck. The designers clearly put a lot of effort into the variety here as well, so often do they throw in inventive special rules and objectives, a lot of which not only change the pace of battle in meaningful ways, but often weave narrative significance into play as well. One of my favorite feelings in this game was getting stuck on a battle because of its particular rules, banging my head against it for a little while, then just suddenly seeing it, and pulling a satisfying victory just before it would’ve started feeling frustrating.

For as much thought and care as was clearly put into the design, though, there’s really only so many ways to keep combat interesting and engaging through a campaign that can last as long as fifty hours. In the back half of the game, combat can too often feel like a grind. At this point, you’ve got a big, diverse deck with plenty of powerful cards that makes it too easy to brute force your way through most situations. I found myself repeating the same tried and true tactics over and over again to bring my game to a speedy end so I could just move on with the story, which I was still very much enjoying. It’s hard to know if more work could have been put in to truly keep the card game feeling novel - Gwent just generally loses its depth once you’ve got mastery over a sturdy deck. I think ultimately, the game is just too long - possibly by even as much as ten hours or so, honestly. That’s not to say that I outright stopped enjoying it at any point; this is unquestionably one of my favorite games of the year, but if I didn’t have to face that grind in the final couple chapters, it very well could have been a contender for the top spot.

It feels a bit too long in the narrative sense as well. Not necessarily the written aspect of the narrative - that all felt consistently strong and inspired throughout the course of this game. But the mechanics surrounding the narrative, in particular the hard decisions you have to make as a result of limited resources, fall flat once the in-game economy feels maxed out. By the final chapter, all my upgrade trees were completely filled and I found myself sitting on a growing surplus of funds, and suddenly making the “right” decision didn’t feel quite as hard.

Despite its cumbersome length, few games surprised and enchanted me this year as much as Thronebreaker. The challenging and compelling role playing, the satisfying card combat...hell, even if that stuff wasn’t as outstanding as it is, I probably would have been happy to spend a considerable amount of time in it for its art style and music alone, so thoroughly did it soak me in those intoxicating Witcher vibes. It made me very excited at the potential CD Projekt Red still has in it for finding innovative and novel approaches to fresh storytelling in a well-worn universe, and I just hope that potential can continue to be realized after the distressingly muted reaction to this game’s release. Here’s hoping that its recent addition to Steam, and its upcoming console release, allows it to find the audience that it deserves.

#Thronebreaker: The Witcher Tales#Thronebreaker#The Witcher#Witcher#CD Projekt Red#Cyberpunk 2077#RPG#Role Playing Game#Card#Cards#CCG#DCCG#Collectible Card Game#Digital Collectible Card Game#Review#Criticism#Podcast#Video Games#Politics#Games

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rockstar’s stumble into the frontier of games mirrors the ambition and exploitation in American expansion (a Red Dead Redemption review)

A little over halfway through Red Dead Redemption 2, our morally confused playable protagonist, the outlaw Arthur Morgan, meets a couple Native American men, two characters who become integral to the main story in the latter part of the game. Their tribe is given no name. Uncharacteristic horns ring at their introduction, providing a fanfare for the vaguely indigenous-sounding music that overtakes the score every time a mission for one of these characters is played. They lament their plight to Arthur, that the US government is once again breaking a treaty they’ve made with these people, displacing them from their land to extract oil. When they ask Arthur for his help, this white man responds with indignation: “There’s a price on my head in two states, my friend. The government doesn’t like me any more than it does you. Like you, I’ve been running for as long as I can remember...and like you, my time here is nigh on done.”

It’s an exemplar of the type of false equivalencies and hollow platitudes about the freedom of nature and the oppression of institutions that the game, like its predecessor, makes an overt thesis out of. What keeps it from falling completely apart is the fact that it basically makes sense that Arthur would believe it to be true: we’re not given many concrete details about his upbringing, but we know that it was rough, that most of his blood relatives are dead, and that Dutch Van Der Linde, the sociopathically charming leader of his gang, acts as a father figure to him and many other young members, people that Arthur considers family. He was raised as an outlaw, and owes his life to his gang, so it makes sense that Arthur never had much of an opportunity to recognize his privilege in comparison to, say, native folks. The problem is, the game doesn’t recognize Arthur’s bullshit any more than he himself does.

Over and over throughout this game, Arthur or other members of the Van Der Linde gang voice beguiling lamentations about the encroachment of society on the West in the year 1899, how, as Rob Zacny at Waypoint recently pointed out in a letter, the world just doesn’t have a use for these people any more, as if the world ever had a use for murderous bandits with no loyalties to anyone but themselves. We’re meant, it seems, to take all this eulogizing at face value, and to feel legitimate sympathy for these characters.

What’s shocking is that it actually, almost, works. Halfway, at least. Despite the derivative, hamfisted, and cynical writing that Rockstar Games has always built their narratives off of, all of which is toned-down but ever present in their most recent release, Red Dead Redemption 2 nevertheless manages to create a memorable and likeable cast of characters, whose personalities get deeply mined through the game’s excessive run time, who feel more fully realized and complex the more time I spend with them, who I can’t help but empathize with. And this, really, is fairly indicative of how I feel about most aspects of the game: it’s a mess, but an oddly endearing one.

--

Has Rockstar ever made an actually good game? I know that in part, that question is frustrated provocation on my part, considering how wildly successful, both critically and financially, each of their games has been, and how influential and groundbreaking to modern AAA game design. But I do ask it sincerely. Their games have always felt at odds with themselves, torn between their open-ended, stunningly detailed and endlessly playful world design, and the stiffly choreographed gameplay their genre-film-aping narratives ultimately force the player into. These narratives often have little to add to the much more nuanced films that they crib from, outside of an unpalatable libertarian cynicism that wields bitter but unfocused satire against just about everything and everyone within the game, the Housers and their writing team often seemingly knowing of no other form of fictive expression. Adding to that, the vehicle for these narratives often boils down to little more than mindless graphic violence, each mission ending up at wrestling with swimmy controls while performing repetitive shooting and/or reckless driving.

When I was a teenager and playing games like Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, my dad often derided the way I played as “not actually playing the game,” apparently dismissing the creative fun I found in poking around the game’s opulent sandbox rather than engaging in the game’s main story missions, which I found more of a tedious necessity in order to open up more parts of the map rather than the main draw of the game or the “way it’s meant to be played.” What he didn’t understand, probably because he never played the games himself, is how much more the world of Rockstar games has to offer than the story missions do. The budget and talent that Rockstar can afford make for some of the most stunningly and exhaustingly intricate open worlds in video games. While I can’t actually speak for the inner dynamics of how these games are designed, it’s always seemed to me that there’s the aspect of the games that Dan Houser and his creative leads focus on, which is the main narrative, and then there’s the actually impressive aspect, the awe-inspiring collective effort of a large team of immensely talented and frequently overworked designers to produce a convincingly living, breathing world that the player can find herself immersed in.

In many ways, RDR2 follows in that same tradition of all previous Rockstar games, first and foremost with the labor abuses committed throughout its production. All of this is well-documented at this point, from the prior knowledge that we had about Rockstar, such as reporting of egregious crunch schedules maintained by employees by their spouses way back around the release of the first Red Dead Redemption in 2010, to Dan Houser’s interview with Vulture prior to the release of this game, in which he casually bragged about 100-hour work weeks, to the exposé that Kotaku’s Jason Schreier released soon after that, detailing various stories of Rockstar’s crunch culture by dozens of current and former employees. Rockstar certainly isn’t the only developer taking advantage of their employees’ passion for their work, and in a way it feels like an odd sort of power to play a game knowing just how bad the labor conditions were. It’s easier facing the realities of the way something was made going into it rather than retroactively, and there were very few moments in my time playing this game where I wasn’t thinking, at least in the back of my mind, about the amount of pressured overtime any given employee had to put in to make the experience that I was having the experience that it was.

It’s hard not to think of this when Schreier started off his massive piece with the story of the late-in-production addition of widescreen black bars during cutscenes, which required massive amounts of crunch within the final year of production to retool the game’s hours of scripted sequences, all in an attempt to make it feel more “cinematic.” Every time I enter a mission, those black bars appear, a stark reminder of the mindset of Rockstar creative leadership. Seriously, fuck those black bars. It’s not just that, as was discussed in a recent episode of Waypoint Radio, it feels like such a sophomoric, pretentious notion of what makes something cinematic, rather than, say, actually thoughtful and meaningful cinematographic choices. It’s also that it was so clearly a rushed add-on that it sometimes doesn’t even work correctly. I lost a solid hour and a half trudging multiple times through a particularly long and slow mission due to a glitch at the end of it, in which those bars refused to go away and trapped me in post-cutscene purgatory several times over, until I finally decided to skip the cutscene altogether. To answer a question Schreier rhetorically asks in his article: no, the black bars were definitely not worth it.

And they’re not the only obvious example of this game’s excesses with blatant disregard for the worth of employee time and energy. Without giving too much away, there’s a section of this game that takes place away from the already massive, staggeringly elaborate main map. From the foliage to the architecture of the environment, it’s obvious that this isolated section is no rework of prior assets that make up the rest of the game (in fact, pretty much no part of the map feels at all copied and pasted from another), but a ground-up, brand-new environment. And it’s so completely unnecessary. The plot drags unbelievably in this section, beating the player over the head with the same repetition of themes and character arcs that already felt played out a dozen hours ago by that point. The gameplay is reduced to the least compelling version of the game possible, a several-hour-long shooting gallery that outdoes any feeling of fatigue I’ve ever experienced toward the end of an Uncharted game. I nearly put the controller down for good in this part, not just out of boredom and frustration on my end, but out of sheer outrage at what a costly and laborious process it must have been to create this section that fucking sucks.