Follow along as I research, discuss, and share progress reports and snippets of my latest novel, "The Maddening Science". This novel was made possible by a grant from the Toronto Arts Council, and is based on my short story of the same name. Read the original short story here. | Listen to the Audiobook of the original short story here. Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | Website | Other Books

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Y'all I know that when so-called AI generates ridiculous results it's hilarious and I find it as funny as the next guy but I NEED y'all to remember that every single time an AI answer is generated it uses 5x as much energy as a conventional websearch and burns through 10 ml of water. FOR EVERY ANSWER. Each big llm is equal to 300,000 kiligrams of carbon dioxide emissions.

LLMs are killing the environment, and when we generate answers for the lolz we're still contributing to it.

Stop using it. Stop using it for a.n.y.t.h.i.n.g. We need to kill it.

Sources:

64K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's my 11 year anniversary on Tumblr 🥳

😨

Well this is humbling. I started this blog to track my research as I wrote this novel and I still have not written this novel.

0 notes

Photo

The old Toronto Star building at 80 King Street in 1963. The ‘Daily Planet’ building in the Superman comic book series was modelled after this building. #oldtoronto #toronto #history #superman (at Toronto, Ontario)

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Link

Bars, pubs, and watering holes.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

#the maddening science#j.m. frey#research#article#toronto#writeblr#am writing#archive#historic toronto#writing blog#writers#criminals

0 notes

Text

#the maddening science#j.m. frey#research#article#toronto#writeblr#am writing#archive#historic toronto#writing blog#writers#1950s#hurricane hazel#weather

0 notes

Photo

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

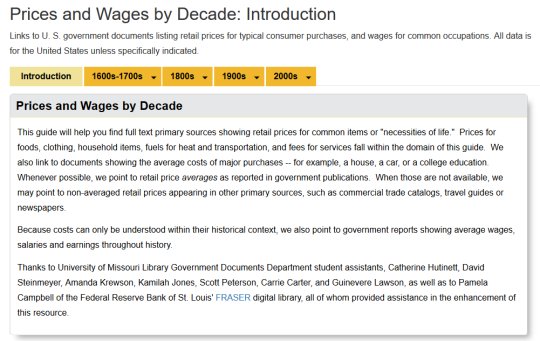

I just found an amazing website for writers.

While I was searching today for some prices of things in the 80s, I found this website:

As you can see, it is full of info about prices of things and of wages in the past (In the U.S. mostly, but it has a few lists of prices in other countries). This is so much more useful than simply an inflation calculator, which doesn’t account for the supply and demand of goods and services, and is often inaccurate.

Some information that you can find here:

- Cost of groceries.

- Cost of a meal at a restaurant.

- Rent prices.

- Cost to buy a house.

- Cost to mail letters.

- Gas prices.

- Bus fares.

…And much more.

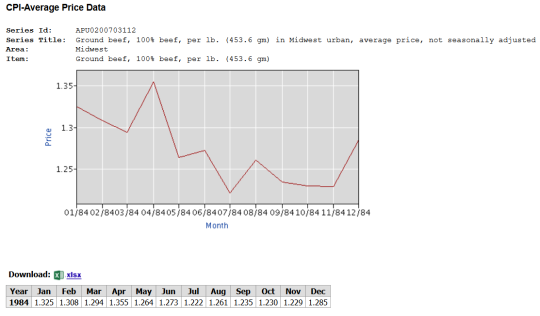

For example, here is the price of a pound of ground beef in the Midwest in 1984:

And not only do they list the prices of things and the general average wage, they also provide average wages for specific jobs.

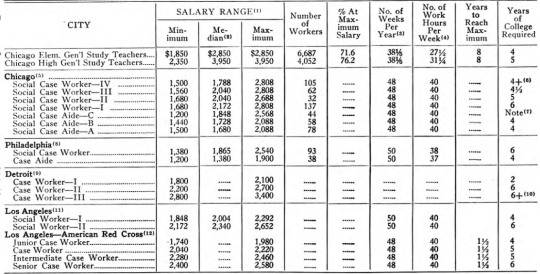

For instance, how much did social workers in Los Angeles make in 1945?

Approximately $2k dollars a year, it seems. (That was $1 an hour!)

So, yeah! I just thought I’d share. Warning, though, it is pretty hard to navigate on mobile. I’d suggest using your computer if you can.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#the maddening science#j.m. frey#research#article#toronto#writeblr#am writing#archive#historic toronto#writing blog#writers#1970s#danforth

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Chapter Two

Ah, hello. Was your lunch as disappointing as mine? I don’t know why I expected different - I’m not so much of a hedonist that food has rated high on the list of things that I require in quality, but I had hoped that because I had a guest someone would have made more of an effort. Ah well.

It is prison after all, Rachel, isn’t it? We are meant to suffer.

Oh, no, I don’t mean to imply that I am starved or served anything that will make me ill. Goodness no. Prisoner rights have evolved significantly since the first time I was incarcerated. Hmm? Oh, I’ll get to that. Patience.

How else do I suffer? Well, the worst part about being a mad genius, as you can guess, is the boredom. Solitary Confinement is a special kind of hell. Not because it is dark, or just the right side of too cold to bring activists and indignant lawyers done on the penury system, or because I am alone. I was quite happy to hear that they were going to be leaving me all alone. It felt like a breath of spring air, a small soft finally. It was lovely to be completely alone for the first time in ages. I don’t hate people, you must understand. But I have had quite my fill, I think. After all the… well, after that.

No, solitary confinement is hell because the only thing I have to do in here is count.

I am assuming that I will be in solitary for many, many years. Potentially as little as twenty-five, a life sentence, which is the standard sentence for the sort of criminal I am. But I was sentenced to one sentence for each life lost in the, ah… ahem. Apologies. I don’t… shall we call it a ‘tragedy’? As the papers elected to do? One thousand seven hundred and fifteen lives - forty-two thousand, eight hundred and seventy-five years in jail, if I serve the all of my first degree murder sentences consecutively. At thirty one million, five hundred and thirty-six thousand seconds per year, Rachel. Can you even imagine how many seconds that is?

And shall I count them all? I just might.

Will I live that long?

Ah. Likely not. Even I have not fully worked out how this little mistake works. Oh yes, it was a mistake. Haste and desperation do not mix well with laboratory protocols, and I was indeed in desperate haste when it happened.

Yes, I promise I will tell you that as well. Patience, please. All in good time.

Forty-two thousand years is a long time to be alone. Well of course I don’t actually believe that they will hold me that long. Two, perhaps three sentences in, I will be declared rehabilitated and released. A hundred years, that’s what I assume. If the prison system still operates the same way in 2132. That is a long time to be alone, and after the events of the last six decades, I welcome it.

But it is also a long time to become bored.

Sometimes I wonder if it isn’t a shame that I cannot be given the death penalty. It’s not humane but it would put an end to things. Sometimes I wonder how I would react if they tried. Sometimes I wonder how they will react if they try and fail. I still am not certain if such a thing would kill me - it is possible that my death may only come with the complete destruction of my every cell. Burning alive, perhaps��

Forgive my gallows humor. I am old and have had more time than most to come to terms with my mortality. Or lack thereof. I don’t long for death, but I sometimes wonder if it would be easier.

To avoid both thoughts of that nature and my boredom, I count. Seconds. Minutes. Hours. Sometimes, when they are available, I count tiles and window panes, buttons on a coat, teeth on a comb, leaves on a tree, ants on tarmac, grey hairs on the head of the man in front of me on the bus.

But mostly I count seconds.

Hmm? Ah, well… good question. I suppose that it… well, it is because of the watch.

Grandpapa’s silver fob watch. I recall it with a preciseness that sets it aside from all of my other admittedly numerous memories. I see it quite clearly in my mind. It glows, almost, with the nostalgia of youth.

Ah, but I’m getting poetic. You see, I forget nothing. I catalogue everything. That is what I Do. It is a small power, an obscure power, it doesn’t stack well against those found in the generations that came after me, but it is the most important, the most useful, and likely the most affecting thing to Do that has ever been recorded in one of Us.

But I was speaking of the watch.

Grandpapa worked on many watches over the years, other people’s watches, in that little street-front shop in that neighbourhood bordering the Player Estates, but I never saw him do anything but check the time on his beautiful art nouveau watch.

It never seemed to wind down. It was never scratched. Perhaps he tended to it dutifully outside of my sight, away from his place of commerce.

It was silver, the watch, with a chain like gossamer. There was a single polished gem where the chain met the loop, a dark garnet. The cover came open like butterfly wings, hinged on the opposite outer rims, and perforated in the same stained-glass way. The design was organic, something swirling and like the curling coil of a climbing vine. The numerals were roman, and the hands were shaped like stamens. They moved slowly, without the quick sharp tick to mark the time, so smoothly that one had to blink to be certain the second hand was moving at all. And the face was ever so faintly blue, like it had been made from a shaved-down sapphire.

A fairy watch.

Or at least, it seems like it must have been. If magic ever existed, if the Fae were real and not just my own primitive ancestors with the genetic abnormality occurring hundreds of generations separated providing both them and me the ability to Do, then I would not doubt for a moment that they had given Lachlan Munson the fantastical watch.

I don’t know what began my fascination with it. Perhaps my Grandpapa had dangled it over my face while I lay in my crib - but memories that old are lost in a mist for me even despite what I am. They are as shrouded behind the gauze of time as they are for most everyone else. I hypothesize it is because a child’s brain is not fully developed immediately upon birth and my genetic gift had not finished blossoming yet. Perhaps he dangled it over me. Perhaps I had been crying, and he sought to distract me by pulling me onto his knee to distract me. Perhaps he was showing me the watch because I was meant to inherit it, and he was trying to forge a connection through his son to his grandchild. Perhaps it had slipped out of his hand as he checked the time. Perhaps I had found it on his washstand.

This is one of the rare times when I can honestly say that I don’t know when I first saw it. Only that it was as tied inexorably to my memory of my Grandpapa as the scent of his aftershave and the calluses on the tips of his fingers.

I also don’t know what happened to the fob watch - I never inherited it. By the time I might have been responsible enough to be given the watch, it was gone. And so was I.

Ah, but I was talking about counting.

I am seven at the time. It was the youngest a child was required to go to school, and though at the time we it was only compulsory to attend for four months of the year, I was as elated to attend as my parents were to find better distractions for my precocious mind and we had agreed that I would attend for the full term.

Being the son of a Playter, even a little known one, had its advantages. The school I attended was populated mostly with young boys and youths of a similar background to my own - upper middle class with merchant parents, all white, and mostly Presbyterian.

Shall I set the scene for you? It’s 1923, and Toronto is small and though dusty and muddy, neat. Few buildings that line the wide roads rise above three or four stories, and wires string along above the sidewalks in multi-tiered groupings. There are elegant office towers downtown, stone and small windows, elaborate cornice pieces and lintel carvings. Outside of those few blocks come the merchant buildings, Georgian red and yellow brick, housing departments stores and greengrocers and family run butchers and barbershops. Then next the row houses and cramped single family homes, dotted here and there with large houses with servants and gardens and low walls around their perimeters - high enough to make it obvious that the rabble is unwelcome, but low enough that the common gawkers can admire the fine lace of the curtains, the well-tended rose bushes, the gleaming windows.

Everyone wore hats outside, and on the roads the last of the horse-drawn vehicles are giving way to Tin Lizzies and early spoke-wheeled Fords, clunky bicycles, and blunt-nosed streetcars. Hair was pomaded, women wore dresses and low heels, men were clean shaven to thumb their noses at their father’s beards. Children played in the streets, or the public parks, and businesses were closed on Sundays so everyone could go to church.

All the photos of the time are sepia and silver, but I assure you there was vibrant colour all around - women’s evening dresses and bright red lips, the lush green of grass and trees, the blue of the lake, the riotous hues of the hundreds of billboards on any surface flat enough to paint or paste one onto it. It is a time of manners, and night-time parties filled with wild music and cocktails for the young, and what crime there was, it wasn’t happening in my neighborhood.

On the first day, the day I began to count, I was sitting on the bottom stair in my short pants and my high socks at the back of Grandpapa’s workshop, waiting for my mother to to come down from the apartment and her toilette. I have just come home from school, and she is preparing to go out with father - this was September of 1923, and the Great Depression was receding. Grandpapa’s business had survived, and father - one-handed as he was - had begun to carve a name for himself on the halls of local council chambers. If there was one thing my father was good at, it was talking. Mama had refused to go begging to her wealthier relatives for support, and had spent those lean years voraciously learning and employing every economizing ‘life hack’ that she could glean, taking in borders who could no longer afford rent on their own apartments, giving up stockings and pomade and cigarettes, and breaking into the trust they had begun for my education. I did not begrudge her that, and in the end I never ended up requiring extra funds for schooling anyway. It was a good thing Mama already owned the building in full before the stock markets crashed or we likely would have lost it.

The back stairs of the building were cramped, and a bit dusty. Like most structures on the Danforth, it was tall - three stories including the ground floor shop and a storage cellar - and skinny, with just enough space between the thick brick firewalls blocking our home from the building over for a table and chairs, or a double bed, while leaving room to walk without barking one’s shins on the furniture. There was a small cellar too, not deep, used for storing Grandpapa’s supplies and our root vegetables and pickles.

The back stairs always carried the dueling scents of Grandpapa’s workshop - mechanical oil and metal - with the upstairs smells of Mama’s perfumes and cooking, Papa’s cigarettes, furniture polish and whatever wilting flowers I could scavenge from the nearby parks to present, filthy and grinning, to my mother. Exactly four steps up, before the bend that took the stairs across the back wall, the scents mixed with perfect evenness, and that’s where I was seated.

The pin curls take extra time, and mother likes to have them just right before they go out dancing. There was a free community

As I wait, blood blossoms against the white wool on my leg, and I hope Mama will not notice. I worry less about her anger at me being untidy, and more that I know it will take an awful lot of scrubbing to get out.

Despite my vow never to lie as an adult, I was not a very honest child. At that moment, I am making up a story that will be less horrifically embarrassing than admitting that one of the older boys, Roger Phillips, had beaten me up because I had objected to certain term he had called me. This version of the story involves aliens and rocket packs. I am also not a very good liar.

The real story is this: Roger Phillips came from the sort of family that used more than three forks at dinner, and had told me, in no uncertain terms, that my father was a useless cripple and that my mother danced to nigger music. That means, he went on, that she was going to turn into nigger, and that made me the son of a nigger. I would be a nigger, too. I didn’t want to be a nigger, because the young black men and women I had seen in Toronto were mostly servants. I didn’t want to be a servant; I wanted to be a boy. And sometimes the black people weren’t treated very well. I wanted to be treated well, so I told Roger Phillips that I was not a nigger, and would never be a nigger and liking Jazz would not turn my mother into a nigger. Secretly, I hoped I was right.

Of course, Roger Phillips was a lying little bastard. But I was seven. And Roger Phillips had said it with such conviction that I had believed him.

I had then surprised myself - and Roger Phillips - by swinging a fist at him.

I had never punched anyone before in my life, but my father had taken me to boxing matches. As I had, even then, perfect recall, I had adjusted my stance and my swing to match that of the great sweating men I saw in my memory, and lashed out.

Now, I must pause here to reinforce that perfect recall is not the same as muscle memory. I had no actual training as a boxer, no practice in making a fist, no experience in any sort of martial art. That I scored a hit at all was due to the aforementioned element of surprise.

The hit resulted in Roger Phillips getting broken nose. It also resulted in me getting pushed into an alley by his mates, and down into a pile of scrap wood and metal. The cut on my leg happened almost at once, and forestalled what I was sure would have been a vigorous beating because I had screamed so loud, and one of the boys got sick at the sight of blood. My leg and Roger Phillips’ face were enough for him and he had vomited into the trash beside me. That had embarrassed the other boys enough that the whole posse had fled and I had been left to hobble my way home, alone and filthy.

I had pulled up my sock to hide the blood, but I had not known at the time that blood stains and spreads, that it seeps through wool just as easily as it seeps out of a cut. I snuck around to the back entrance to the workshop and dashed by Grandpapa to the water closet on the second floor to wash the dirt off my face and hands. Mother couldn’t abide smudgy kisses, especially after she had put on her face.

As I wait on the step, as I did every night, I pull my homework out of the leather satchel that serves as my school bag and begin my arithmetic problems. Grandpapa only lets me sit up and play chess with him if my homework was finished, and Grandpapa’s chess lessons are significantly more interesting than my homework.

I remember that Father came downstairs first, dapper as always and smiling around a slim cigarette that balances just so right in the centre of his bottom lip. It was a trick I often attempted to mimic with the sticks of lollipops and could never quite manage.

He kisses the top of my head, as always, and says, in this thick brogue: “Righto, sport? And how was school today?”

“Boring,” I reply, as always. “Father, can’t you make the teacher give me harder problems?”

Father ruffles my hair. “Now, what’s the point in that, my lad? Then you’d have to advance past the other kids, and being the little fish in a big pond is not all it’s cracked up to be. Much better to be a big fish in a small pond, boyo.”

“I’m a small fish no matter what pond I’m in,” I protest, but father has stopped listening. He is smoothing out his mustache in the tarnished mirror by the back door, and throwing his cuffs to ensure they sit right against his suit sleeve. His other sleeve is tucked up to his elbow, pinned discreetly so the bulk of rolled fabric doesn’t bring extra attention to his missing hand. He is dapper, and handsome in his one remaining good suit, carefully preserved and quietly patched these past four years.

He is not negligent of me or my concern. He is simply madly in love with my mother and is always just a little unsure how he landed such an amazing woman. So he tries very hard to be worthy of taking her arm. Sometimes he gets distracted. But he means well.

Meant well. He is sixty years dead, and committed to the present as I am, I sometimes forget.

But back in that memory, the soft click of heels against the hardwood stair make both my head, and my father’s swivel on our necks.

“Woooeee,” father says softly. “Now lookit that. Ain’t that just a dame who’s the bees knees?” The slang sits like rocks in my father’s mouth, awkward and roughened by his accent. He tried so very hard to be relevant to the folks he wanted to please - mother’s family, the people of the neighbourhood, the men of the political endeavors that he sought to

“Scamp,” Mama teases from the top of the stairs. Even now I can envision her deliberate decent, black-lacquered nails skimming the banister, dark lips curved in a flirtatious smile as her kohl lined eyes flicked at my father, then indulgent as she turned them to me. “Oh, dear, and scamp,” she admonishes, gaze narrowing on my wool socks, somehow managing to see them from her place above me on the stairs. I am convinced that this is something that all mothers can Do, whether they are one of Us or not. “Oliver?”

It is a question only in that her voice inflects upward. In every other way it is a demand for answers couched in disappointment.

“There was a spaceman. He said he was from Venus and the backwash from his jet pack made me fall into a—”

“Oliver,” she interrupts, and her darkly painted mouth is a fearsome thing to behold as it curves down. As much as I was a dishonest child and a poor liar, I was also an unbelievable mama’s boy. All of my clever tales of rocket ships and aliens crumble on my tongue.

“Phillip Rogers called you a nigger because you like jazz,” I say softly. “So I hit him. Then they pushed me down.”

“Oliver!” mother says.

“Hit him?” father shouts at the same time.

“Like this,” I say, and show him the right hook. Father grabs my wrist mid-air and inspects my knuckles. They are scraped. I hadn’t noticed.

“Oliver, my lad, this is unacceptable,” father tuts. Grandpapa keeps a bottle of cheap Scotch in one of his work table drawers, and our commotion has summoned him with bottle and clean handkerchief. He dabs his pocket handkerchief into the liquor and applies it to my hand. The sting is fair punishment. “Men don’t hit other men,” he rumbles at me.

“But men defend their dames, you said so,” I protest. “Besides, Papa shot people in the war.”

Papa kneels in front of me. He puts his hands around my shoulders. “That was something different, Oliver. Fighting should be avoided. Don’t be a dummy. And besides, your gorgeous mother is my dame to defend, not yours.”

“I wish you gentlemen would stop calling me a dame,” mother protests half-heartedly. She’s made her way around me and has joined father, crouched down by the bottom stair - not kneeling, she wouldn’t want to get a pull in her stockings - and peeling down my wool sock, revealing the cut there to her disapproving eyes. I gasp at the unexpected pain of the fresh air slapping against the cut, and grab at her shoulders. Normally she would admonish me for wrinkling her dress, but now she just leans in and kisses my neck.

Father cranes his head and pecks a kiss to her raised arm, right on the elbow. “Oh? And what should I call you instead? What do the young swathes say today? The cat’s pajamas?” He kisses her shoulder. “My ducky?” Her neck. “My doll?” Her chin. “My tom-ah-tah?” The tip of her nose.

Mother slaps his shoulder playfully. “As long as it’s not late to dinner.” She winks broadly at me and I laugh obediently. The joke hasn’t been funny since I was three, but it makes her laugh in return, and I dearly like her laughter.

“Off to your grandpapa with you,” Papa says, pointing to where his own father has retreated to stand by the wall beside the water closet. “He’ll have a look at your leg. Do you need a stitch?”

“Don’t think so,” I mutter. Grandpapa is going to put iodine on it and it’s going to sting and I don’t want to go.

“I don’t think so,” mother corrects. “Full sentences, Oliver.”

“Yes, mother. I don’t think so.”

“That’s my boy.” She ruffles my hair. “What a hero you are, defending your mama like that. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome, mama,” I say.

“But no more hitting,” father adds.

I squint at him for that. “But what if they really deserve it?”

“No.”

“Can I hit a mobster?”

“No.”

“What if they’re robbing a bank?”

Father shifts his cigarette in an exasperated grin. “Fine, okay. You can hit mobsters if you catch them robbing banks.”

“Okay,” I agree. I hold out my hand so we can shake on it, and father, all playful solemnity, grasps it. We shake. “It’s a deal.”

“It’s a deal,” he says. “Now, do as your mother says. Water closet. Grandpapa and you can have dinner after - I’ve laid out your plates and there’s cabbage rolls in the oven.”

“I don’t like cabbage,” I complain.

“But I do,” mother says and kisses the exact middle of my forehead. “Off you go Oliver.”

She stands and I do as I’m told. Grandpapa lays a warm hand on my shoulder, comforting, supportive. Mother stands and pats her hair, then smooths out the wrinkles my little fingers had wound into the shoulders of her dress.

She pecks father on the cheek, then rubs away the lipstick with her thumb.

“Should I teach him how to throw a proper punch?” father asks her as he opens the back door for her. They’re so wound up in one another I think they’ve even forgotten that I can still hear them as they step into the back alley, making their way down that toward the cross street that will allow them to access the Danforth and stroll at their leisure to the community hall and the dance.

“Absolutely not,” mother says, as she lingers by the door, throwing a look over her shoulder at me. “Not until he’s ten, at least.”

“Boys will be boys. He’s going to scrap whether we condone it or not, Flo. I’d rather he knew how to end the fight with one good right hook.”

Mama sighs. “We’ll talk about it in the morning. How’s that?”

“Sure, whatever you say, darling.”

“Butt me, my dear,” Mama says, and Papa obligingly pulls his cigarette case from his jacket pocket with his one hand and flips it open. Once she’s plucked one out of the case, he pockets it and comes back up with his zippo, which he flicks open. Mama reaches up to touch the tip of the cigarette to the flame. I memorize that, too, the easy charm of it, the economy of movement. The fact that he obviously practiced to be able to do the whole routine smoothly with one hand.

And then, in a swirl of smoke, they are out the door and down the walk.

“Come, sit,” Grandpapa husked at me, and I toed off my shoes and yanked off my socks and sat on the closed lid of the toilet.

The iodine stung as much as I expected and I winced and almost succeeded in holding still. Grandpapa has hold of my ankle to keep me steady and my hands are fisted in his shirtsleeves and he is gazing intently at the cut with his loupe.

“Not too bad, lad,” he murmurs over the cut, cleaning away blood and dirt. “But I’ll be needin’ my tweezers for these splinters, I’m thinkin’.”

“Oh, no,” I blurt, trying to jerk away and Grandpapa lets me go.

“Here now,” he says, comforting and gruff, standing. “I’ll be right back. Sit still.”

“Yes sir,” I reply glumly, and he is back right away with said tweezers and an oil lamp besides. He puts the lamp down on the floor by my leg and begins the grisly business.

Despite the pain, after a while the boredom comes.

If you ever write this confession down, make sure you transcribe that with a capital letter - The Boredom.

I didn’t know how to explain it then, save that it was a kind of deep, brown mood that yanked me into spirals of dissociation and empty staring as my brain went dark and dumb, or a spinning mind and limbs that would not rest, my mind flashing and popping without tempo like a string of cheap fireworks. It was encompassing and happened whenever there was nothing particular to occupy my mind. If I already knew what the teacher was explaining, or if I had completed a book and had nothing further to read, if the games of the other children were not engaging in their complexity, if the conversation of the adults around me was repetitive or outside of my understanding simply by dint of not being privilege to specific facts or information. I required stimulation at all times, and at this point was too young to know how to seek out that stimulation myself - I had no library card of my own, no laboratory, no adult who yet understood how deeply, frustratingly unoccupied I often was.

I start to fidget. Mama hates it when I fidget. That’s what she calls it when I start counting the ceiling tiles, head right back on my neck and lips working silently over each number, counting the small wrinkles in my skin, or the number of small round scabs. This time I was starting at Grandpapa’s head, fingers tapping on my thigh to keep account, trying not to jerk out of Grandpapa’s hands as he worked and jiggling the other leg to expend the energy the the pain sent zinging up my spine.

“What are you doing, Olly, my boy?” Grandpapa asks.

“Counting,” I answer, because the one person I never lie to is Grandpapa.

“Counting what?”

“How many black hairs you have,” I say. “I was going to count the silver ones, but there are too many. They are too close together and I can’t see them all individually. But the black ones stand out.”

Grandpapa runs a wrinkly hand over his pomaded hair and chuckles. “I see. And when you’re done counting those?”

“Maybe I’ll count the ceiling pattern again, though that never changes.”

Grandpapa’s dark eyes narrow. “Do you count a lot, Olly?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What sorts of things do you count?”

“Blades of grass, clouds, the checks on the back of Edith Parker’s dress,” I admit slowly. No one’s ever asked me before. “She sits in front of me in class, even though my last name comes before hers in the alphabet. She was too short to sit behind me.”

Grandpapa leans back and studies me. “Why do you count, Olly?”

“Because sometimes I have nothing else to do, sir.”

“So talking with your Grandpapa isn’t stimulating enough, eh?”

I feel my cheeks going red. I am embarrassed. “That’s not what I mean,” I protest. “I mean, I can listen, and I can answer, and I can count all at the same time. I am really good at school, so, when a test is over, or something like that, and I’m waiting for the other kids to finish, and they’re slow, I count. In my head.”

“Seems like sometimes you fight, too.”

“Only today,” I promise. “Never again.”

“Don’t make promises you don’t you’ll be able to keep,” Grandpapa says, and sets aside his tools. I’ve been so engrossed in counting that I hadn’t noticed that he had finished, wrapping my leg snug with some of the hospital gauze that Mama, ever the nurse even now, insists on keeping in the medicine kit.

“But I won’t–”

“You won’t intend to,” Grandpapa says, washing his hands. Not knowing what else to do, I say on the toilet. “But sometimes a fight comes to you, without you meaning to. Let’s go up to the kitchen, there’s more space there.”

Grandpapa takes the time to throw the bolt on both of the downstairs doors and turn his shop sign over to ‘closed’. And then, standing beside the kitchen table, Grandpapa shows me how to curl my fingers into the kind of fist I can use to strike a person without breaking my own fingers.

When I’ve punched his palm to his satisfaction, we dish out our cabbage rolls and part way through dinner I resume counting his black hairs.

"Alright then.” Grandpapa digs his watch out of his pocket and flips it open. The glass face is polished and shiny. “Come sit on my knee, Olly,” he says, and I do, eager to scramble into his lap and cuddle against his heartbeat. “Can you read this?”

“It just says I, two Is, three Is, I and V—”

He chuckles, cutting me off. “Those are roman numerals. It says, one, two, three, four… Do you see the pattern?”

“Oh! V is five? Is X ten?”

“Yes. My, you are a clever boy.”

“Why doesn’t your watch have numbers? I thought watches told you the time, but it doesn’t have the time, it has all the times.”

“Olly, my boy, let me show you how to read the time. This is the hour hand. This is the minute hand. And this is the second hand. Do you see it moving fast? Tick, tick, tick. Like you, the second hand likes to count. One, two, three, four…”

“What is it counting?”

“Seconds. The precious, wonderful, important seconds that make up the moments of our lives, ticking by.”

“That’s something worth counting,” I venture softly.

“And how,” Grandpapa whispers back.

“When does the second hand stop counting?”

“Never, Olly my boy. Never.”

#the maddening science#writers#writing community#writeblr#writblr#free preview#Sneak Preview#sneakpeek#sneak peek#novel#science fiction#science fiction novel#j.m. frey#snippet#manuscript#manuscript snippet

3 notes

·

View notes