Tale type 550 according to the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification index.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Analyzing “The Golden Bird” Through Propp-R Functions

Story genres tend to have familiar or often-used elements in style or narration, and fairy tales are no different. One list of narrative elements commonly employed in fairy tales was created by folklorist Vladimir Propp. This list is known quite simply as the Propp’s functions of fairy tales. The original list includes thirty-one elements; however, there is a revised version (called “Propp-R”) that has been reduced to five or six key points. In this response, I will analyze The Golden Bird through the lens of these Propp-R narrative elements.

The Propp-R stages begin at zero, so to speak, as the very first stage is one that is admittedly not always present in every tale. This stage requires that there be a period of “initial harmony” (Mellor), which does not explicitly occur in The Golden Bird but is somewhat alluded to. After all, it is presumed that peace once existed, and that there was a time before the Golden Bird began to steal the king’s apples. It is to this time that the king would like to return, which segues nicely into the next stage, in which the characters perceive that they are in want of something. In this case, the king wants to know where his apples have been disappearing to.

The second stage requires a quest to rectify the wanting of the first stage. When the prince is sent out to find who has been stealing his father’s apples, this stage is being fulfilled. It is typically on this quest that the protagonist encounters someone (or some creature) who will either aid or confound their quest. This figure in The Golden Bird is the enchanted fox who gives the prince the help he needs to complete his trials—which, coincidentally, comprise the fourth element of the Propp-R functions. For the prince, his trials are to claim the golden items from each of the three kingdoms. Finally, the protagonist attains some prize for their efforts. Here is where we see the prince live happily ever after with the princess, whom he reunited with her brother.

Thus, it is clear that The Golden Bird quite precisely follows all of the Propp-R functions. While obviously only one tale out of hundreds, this nonetheless provides some validity to Propp’s claims that fairy tales have a certain structure. One particular point of interest that arises in mapping The Golden Bird specifically to these stages, however, is that in some ways, The Golden Bird seems to go back and cycle through the different elements before finally arriving at the Propp-R’s conclusion. That is, each kingdom the prince encounters is experiencing its own lack, and sends him on a quest during which he must hope for his fox helper to come and aid him, at which point he must undergo a test to claim the golden item. And so, even though a tale might follow the Propp-R function overall, it may not do so in an expected or linear manner.

Sources Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Sixty Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Edgar Lucas, Weathervane Books, 1979. Mellor, Scott. The Tales of Hans Christian Andersen. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2010, http://vanhise.lss.wisc.edu/~aschmidt2/danish/hca/glossary/propp.html.

0 notes

Text

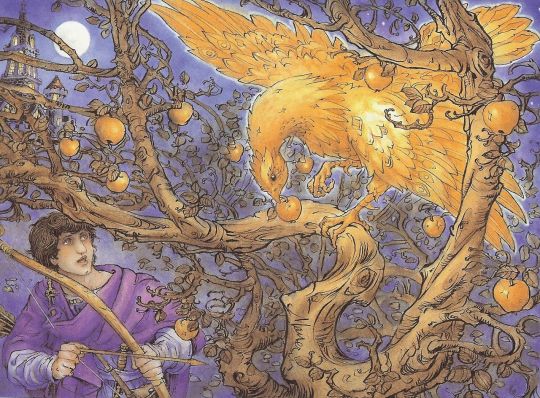

This illustration was done by Mercer Mayer, I believe for the Favorite Tales from Grimm collection. With its brighter colors and focus on the Golden Bird, this illustration is far more whimsical than the artwork by Arthur Rackham that I have also shared. Mayer also portrays the prince as younger and more boyish than Rackham, which highlights the prince’s naïvety.

I like this piece because it draws upon more of the fantasy elements that many of us associate with fairy tales. Something about it—probably the style and the castle in the background—reminds me of a Disney movie.

0 notes

Video

youtube

“Kin no Tori” is a 1987 Japanese animated film based on The Golden Bird. While this film shares many similarities with the Grimm’s tale, the plot does diverge from its source material in a few key ways. For one, the witch (who is only referenced in passing in the original tale) becomes the story’s key antagonist. The main characters also seem to be quite younger than they are in the original tale, perhaps to make the movie kid-friendly. Similarly, many of the tale’s darker scenes—such as when the prince cuts off the fox’s head and paws—have been altered or omitted.

0 notes

Text

Away they flew over stock and stone, at such a pace that his hair whistled in the wind.

Here is an illustration by Arthur Rackham, included in the Grimm's collection from which I found my translation of the tale. Depicted is the first instance in which the fox bids the prince to ride upon his tail, which seems to be quite the feat on the fox's part. Just look at how tiny he is!

In that vein, the fantastical elements of this image are quite subtle. The fox is an average fox, not drawn larger-than-life to better accommodate the prince’s size. This evokes a slight feeling of the uncanny, since as viewers we know that it is not feasible for someone to ride upon a fox’s tail as such, and yet this painting asks that we suspend our disbelief regardless. By doing so we share in the slight sense of wonder that has been painted upon the prince’s face.

0 notes

Text

“The Golden Bird” as World Literature

If world literature is, by David Damrosch’s definition, “all literary works that circulate beyond their culture of origin, either in translation or in their original language” (Damrosch 4), then “The Golden Bird” certainly qualifies as world literature. Despite not having the same reach or cultural impact as stories such as Cinderella and Snow White, this tale has demonstrated some cross-cultural influence, from Norwegian to Scottish retellings. What’s more, these retellings are not rote; indeed, each version contains its own cultural nuances and variations.

The Grimm brothers were writing their Kinder- und Hausmärchen at a time when the monarchy wasn't far from the minds of the German public. It thus makes sense that the brothers included monarchical elements in “The Golden Bird”—that is, the prince in this tale is much at the mercy of the different kings he encounters and must act upon their whims to complete his quest. In Asbjørnsen and Moe’s “Gullfuglen,” however, the monarchy does not play such a primary role. Instead of kings, the prince in this tale encounters three trolls who send him on his various tasks.

Trolls feature prominently in Norse mythology and Scandinavian folklore. They are not known for being particularly clever and “sometimes steal human maidens” (Encyclopedia Britannica), elements that clearly come into play in “Gullfuglen.” By including these elements in “Gullfuglen,” Asbjørnsen and Moe have made “The Golden Bird” tale more culturally relevant to Norwegian audiences.

Andrew Lang has made similar edits in his variant of the tale, entitled “The Golden Blackbird.” In this tale, Lang has changed the helper character from a fox to a hare. By doing this, Lang intensifies the tale’s fantastical elements in ways that are specifically relevant to readers familiar with Celtic beliefs, for in Celtic mythology “the hare has links to the mysterious Otherworld of the supernatural” (Transceltic).

Thus, while “The Golden Bird” might not have the same cultural reach or impact as some more popular tales, it nevertheless has shown some cross-cultural impact. Damrosch warns that in the world of translation and adaptation, “we can gain a work of world literature but lose the author’s soul” (34). I would say that “The Golden Bird,” however, hasn’t at all suffered from a loss of soul. Changes in the Scottish and Norwegian variations of this tale are modest at best, and at the core of all of these tales is a message of perseverance, kindheartedness, and triumph over evil that is cross-culturally relevant and underscores “The Golden Bird’s” deserved credentials as a piece of world literature.

Sources Asbjørnsen, Peter and Jørgen Moe. “The Golden Bird.” Multilingual Folk Tale Database. http://www.mftd.org/index.php?action=story&act=select&id=3302. Damrosch, David. What is World Literature? Princeton University Press, 2003. Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Sixty Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Edgar Lucas, Weathervane Books, 1979. Lang, Andrew. “The Golden Blackbird.” Internet Sacred Text Archive. http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/lfb/gn/gnfb16.htm. “The Importance Of The Hare In Celtic Belief And Our Duty To Protect All Wildlife.” Transceltic. 24 Sept. 2017. https://www.transceltic.com/pan-celtic/importance-of-hare-celtic-belief-and-our-duty-protect-all-wildlife. “Troll.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 17 Aug. 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/troll.

0 notes

Text

Sexism in “The Golden Bird”

A common critique of fairy tales is that they are rooted in sexism. Think Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel—stories of oftentimes helpless princesses and princes who swoop in to save the day. Of course, every critique is met with challenge—as Maria Tatar questions in the introduction to her book The Classic Fairy Tales, “Whom are we to believe? Andrea Dworkin, who contends that fairy tales perpetuate gender stereotypes, or Alison Lurie, who asserts that they unsettle gender roles” (Tatar xiv)? The answer is far from simple; for every tale featuring a helpless female lead, one can surely conjure an example of one where a woman saves the day. The Brothers Grimm tale “The Golden Bird” happens to, perhaps unfortunately, be an example of the former; that is, if a case is to be made for fairy tales disrupting gender stereotypes, “The Golden Bird” is a tale that should not be included.

The characters in “The Golden Bird” are predominantly male. At the helm we have the youngest prince, who is not portrayed as particularly clever or brave—as his father laments, “he has no backbone.” What he lacks in bravery and cleverness, he makes up for in kindness, which is simultaneously his making and his undoing. He does not want to disrespect the Golden Bird or Golden Horse so he does not leave them in the wooden cage or saddle them in wood and leather respectively; likewise, he is sympathetic to the princess’s lamentations and allows her to say goodbye to her parents against the fox’s advice. He is a foil to his brothers, who are portrayed as witty and brave but are selfish and cruel; they both threaten the well-meaning fox and attempt to murder their brother. This distinction allows for an overarching message of good triumphing over evil when, at the end, the Prince attains his happily ever after; however, it also highlights the young prince’s commonness. Though he is a prince, he is simple and good—a representative of the common folk more than the aristocracy. Here, the “Volk” influence of the Grimm Brothers’ tales really shines through (Wilcox 2).

But what of the tale’s sole female character, the Golden Maiden? She almost entirely lacks agency or personality. The Prince doesn’t even have to speak to her to convince her to go along with him—he jumps at her out of nowhere, kisses her, and at once she is “quite willing to go with him.” When she believes the young prince to have been killed, she does nothing but cry every day until he returns, at which she proclaims, “It seems to me that my true bridegroom must have come.” It seems that her life is completely tethered to the Prince’s from the moment he kisses her. The most agency she possesses throughout the tale is towards the end, when she defies the older princes’ death threats to tell the King of their attempted fratricide. Even still, it seems that the Prince and the Golden Maiden exemplify some of what Andrea Dworkin referred to as the “Great Divide:” the Prince claims the “Great Steed” (in this case, the Golden Horse) while the princess exists as little more than an object to be desired (Andrea Dworkin, as cited in Tatar xiii).

Overall, the men in “The Golden Bird” have more agency and personality than the text’s sole female character. This contrast between the portrayal of the King’s sons and the Golden Maiden underscores the criticism that fairy tales often play into sexist conceptions of gender. It is important to note, however, that “The Golden Bird” first appeared in the Grimm Brothers’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen around 200 years ago. In many ways, this tale reflects the social and gender norms of that time—but fairy tales are adaptable by nature. It would be interesting to see what a twenty-first century take on this tale—perhaps with a stronger female presence—might look like.

Sources Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Sixty Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Edgar Lucas, Weathervane Books, 1979. Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales. W. W. Norton & Company, 1999. Wilcox, Brandy E. “Brothers Grimm.” Article. Wiley Blackwell Companion to World Literature.

0 notes