Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

aTONEment: The Podcast

https://moonstoneartscenter.org/moonstone-podcasts/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shawn’s Story*

Shawn’s fable unfolds along the banks of the rivers that authors, Langston Hughes and James Joyce traveled. Also, here to be found is the River Delaware as it flows through Philadelphia and environs. Among other themes, this is a tale of incarceration and deportation. Waiting at the story’s edges, readers will notice that we also meet with a lot of homework, –and a very discerning librarian.

(Above) Image Taken from Salmon Ireland’s web site (Salmonireland.com), is a landscape photograph of the River Foyle.

The Letter

Hi Pops, thanks for your letter. Too bad, the prison blocked a lotta words out. What I got was that you’re getting to go out with work crews to pick up trash on the highways. It must be weird being chained together like that and having guards with shotguns and such watch over you guys while you’re just basically cleaning the roadside. I really like the part where you said that you all go up to the highway right next to the river and that you always take a minute from sweepin or whatever to look out over the riverwaves and see the sun reflect on the swelling banks and feel the breeze. So, that was a really good idea where you said if after work some day I walk to the far end of the Wal-Mart parking lot on Delaware Avenue where it comes up on the river that I’ll be looking out over the same Delaware River as you seen earlier, and I’ll be seeing the same waves, and the same currents, and the same mists and breezes playing off the wave- tops, hearin the same sounds and tasting that little bit of sea salt that the river has from its trip out to the ocean. Imma do it. I miss you, Pops. If I go down that parking lot where it looks across to Camden on the opposite bank on the same day maybe when y’all been out on the highway cleanup crew in your orange prison suits, I’ll be able to catch up with your spirit, at least. And, I’ll say all the stuff you used to listen to me carrying on about. How muad I get at everything and how sad and sorry I feel about other stuff. Remember? I ain’t seen Mom or Dad at all for a long time. But Aunt Helen came down from the convent last week and helped me clean the place. So, we scoured the joint from “stem to stern” just like you always used to say. “FROM STEM TO STERN.” I kept repeating that and then Aunt Helen and me was laughing about the way you used to say it and about how you talk and your Irish accent, “From Stem To Stern,” like a pirate or something. Haha. Don’t get mad. I miss you. Pops. Love You. Shawn.

Saturday Morning: The Library

Shawn: Did you see a piece of paper with writing on it? … like a letter?

Librarian: (Curtly, not looking up from her desk.) No.

Shawn: I was in here after work last night trynna do my homework, and wrote the letter, and now I can’t find it.

Librarian: (Still not looking up.) Why don’t you check around the table where you always work.

Shawn: Where’s the maps of Ireland. They say my grandfather might have to go back there even though he doesn’t want to.

Librarian: (Still looking down. Staccato.) Geography. Under Great Britain.

Shawn: (With an angry edge.) It’s not in Britain.

Librarian: (Looking up.) Yes, It is. Aisle 4, Shelves 10 through 17. Clearly labeled Great Britain including Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Shawn: (Pointing to the green tattoo on his forearm) Just remember, 26 Plus 6 equals ONE.

Librarian: (Loudly, Pointing Finger at Shawn.) Quiet.

Shawn: (Louder.) No!

Franklinville High School

I had already found the letter on the floor in the back of the classroom while grading papers and cleaning the room on Friday evening. That’s when I read the letter and realized that Shawn must have dropped it that day during class. Shawn was new in our school. His body language was terse. He seemed beaten and bent inward. He refused to make eye contact. He never talked in class. When I asked him why he slept on his desk everyday, he said that he worked most nights and that he was exhausted all day. That’s all I knew about Shawn. But then, I looked at the address on his file and recognized that the neighborhood where Shawn lived was near the block where my grandfather owned a bar many decades ago. Jimmy’s Pub opened at 7 in the morning for guys coming off the night shift at the Stetson factory and for other graveyard workers. And some 7 a.m. drinkers were guys on their way out to jobs they hated in center city offices and, then, there were the guys who had been out all night drinking and wanted one last shot before they did their daily perish. Cousins right off the boat from Ireland lived above the bar. I worked there while I was going to college. It was a hole of a place where I learned the codes of the Belfast streets thousands of miles away, streets that I’d never actually seen. I could imagine Shawn’s grandfather, his aunt and the way that prison must have shaken them up and spit them out emotional wrecks fractured by fear, frustration and anger, fractured people living fractured lives.

Over the weekend, I read the letter over and over and wondered how Shawn would feel about my seeing his message to his grandfather. I put it in an envelope and wrote a simple note, “Found on Floor of Classroom” and, then, I noticed that I had planned for our class had to read Modern writers like Langston Hughes and James Joyce. So, I decided to begin on Monday with with a meditation. I planned for us to read the Langston Hughes poem that begins, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

Before class, when I gave the envelope to Shawn, he tore it open and sat down immediately in one of the desks at the front, disclosing the letter’s folds and smoothing out the page while he read it, running his fingers along each line as he read. Class started and he looked at me and I smiled at him hoping to silently say, “yes,” with the smile, yes, I read the letter. Shawn hesitated, looked down, then looked up again and smiled back, nodding. Then, I handed out a worksheet asking the entire class to meditate on the lines that Langston Hughes wrote as a young poet, traveling along the Mississippi River in a train headed South:

“I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

I played the music that the jazz musician, Gary Bartz composed to accompany the Hughes poem. I asked just one question beneath the poem’s lines.

“As you read, how do you connect the poet’s rivers to his soul?”

After class:

Shawn: Mister, thanks for finding the letter.

Me: I felt lucky to read it, Shawn.

Shawn: I’m not sending it cuz I just learned that my granda is going to the prison’s hospice which means that he’s very sick.

Me: (Pausing, lump in throat.) He must be very proud of you. I think you should send it to him or give it to him when you visit.

Shawn: I ain’t got the time or the money.

Me: Still, he must be proud of you.

Shawn: I don’t know if they’re gonna send him back to Ireland or keep him here cuz he’s so sick. My aunt told me about this hospice thing on Friday night when she visited from the convent in Allentown where she works.

Me: The worst part must be not knowing what’s gong to happen, right?

Shawn: (Crying, as he looked away as if he were seeing the far shore of a river through his tears, and quoting the poem.) And My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Me: It’s quite a poem, Shawn.

Shawn: I’ll think about it at work. It’s really good.

Me: Don’t forget your homework. (Smiling, ironically).

Shawn: I never forget my homework. (Smiling back, ironically).

Homework

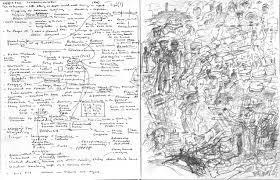

Translate the following passage from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake into your own words. Remember that this excerpt is taken from the end of Anna Livia Plurabelle’s section of Joyce’s novel. Hint: The River Liffey is the scene of this passage, all of which occurs not during the day but at night deep in the language of a very long dream about all rivers.

Monday Evening: The Library

Shawn: Do you wanna hear my homework?

Librarian: I’m busy. Don’t you work today?

Shawn: I skipped work to do my homework first then walk up to the Wal-Mart parking lot to be on the river for a minute.

Librarian: (Smiling). Aren’t you very organized, Shawn?

Shawn: This guy from Dublin’s book is all rivers. You wanna hear my translation of his story about rivers?

Librarian: Yes. But quietly.

Shawn: I’ll whisper it. It’s even better that way.

Librarian: You are a very strange young man. Have you been told this?

Shawn: (whispering)

I can barely hear you with the waters of the river.

The waters chitter. The bats flitter.

Are you not going home alone?

Think of the waters of the River Liffey in Dublin?

Think of the waters of Lough Neagh near Belfast?

I feel as old as that Elm Tree over there.

This is Shawn’s story. This is Seamus’s story.

Good Night, Grand farther, the farther away you go.

Shawn means John.

Seamus means James.

Who were John and James sons or daughters of?

Goodnight, Pops.

Tell me another story about plants and rocks.

Please tell me.

Beside the waters, there hither like the Delaware River.

There thither like the Liffey, the Shannon, the River Erne,

The River Boyne, The River Foyle.

Now, I’m with you beside the rivering waters

The hitherandthithering waters of

Goodnight ……..

Librarian: (Looking up, mouth open in astonishment.) And you wrote that based on the passage in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake?

Shawn: (Nodding. Smiling. Agitated). And now I have to get over to the Wal-Mart parking lot to listen to see the river and tell it what I can hear and telepath it all to my granda who’s up north waiting for the words to echo their way up and back to him.

Librarian: You seem relieved.

Shawn: Of course, it’s sad but I have to say good bye.

(Above) Clinton Cahill’s exhibition “Illuminating the Wake,” which are Cahill’s interpretive drawings on the text of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, synthesizing his encounters with the novel’s dreamscapes. Taken from the web site of the James Joyce Centre in Dublin (https://jamesjoyce.ie/illuminating-the-wake-no-31/).

(Above) Image from web site of Monica and Tyler Aiello’s gallery exhibition titled, “I’ve known Rivers,” which are images based upon the poetry of Langston Hughes (http://www.studioaiello.net/).

*All persons mentioned in this story are fictional (and bear no connectin to actual, historical persons) with the exception of Langston Hughes and James Joyce. All places, also, with the exception of the Wal-Mart parking lot overlooking the Delaware River also are fictional.

(Below) Youtube Musical Composition by Gary Bartz, based upon Langston Hughes’ poetic lines, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shawn’s Story*

Shawn’s fable unfolds along the banks of the rivers that authors, Langston Hughes and James Joyce traveled. Also, here to be found is the River Delaware as it flows through Philadelphia and environs. Among other themes, this is a tale of incarceration and deportation. Waiting at the story’s edges, readers will notice that we also meet with a lot of homework, –and a very discerning librarian.

(Above) Image Taken from Salmon Ireland’s web site (Salmonireland.com), is a landscape photograph of the River Foyle.

The Letter

Hi Pops, thanks for your letter. Too bad, the prison blocked a lotta words out. What I got was that you’re getting to go out with work crews to pick up trash on the highways. It must be weird being chained together like that and having guards with shotguns and such watch over you guys while you’re just basically cleaning the roadside. I really like the part where you said that you all go up to the highway right next to the river and that you always take a minute from sweepin or whatever to look out over the riverwaves and see the sun reflect on the swelling banks and feel the breeze. So, that was a really good idea where you said if after work some day I walk to the far end of the Wal-Mart parking lot on Delaware Avenue where it comes up on the river that I’ll be looking out over the same Delaware River as you seen earlier, and I’ll be seeing the same waves, and the same currents, and the same mists and breezes playing off the wave- tops, hearin the same sounds and tasting that little bit of sea salt that the river has from its trip out to the ocean. Imma do it. I miss you, Pops. If I go down that parking lot where it looks across to Camden on the opposite bank on the same day maybe when y’all been out on the highway cleanup crew in your orange prison suits, I’ll be able to catch up with your spirit, at least. And, I’ll say all the stuff you used to listen to me carrying on about. How muad I get at everything and how sad and sorry I feel about other stuff. Remember? I ain’t seen Mom or Dad at all for a long time. But Aunt Helen came down from the convent last week and helped me clean the place. So, we scoured the joint from “stem to stern” just like you always used to say. “FROM STEM TO STERN.” I kept repeating that and then Aunt Helen and me was laughing about the way you used to say it and about how you talk and your Irish accent, “From Stem To Stern,” like a pirate or something. Haha. Don’t get mad. I miss you. Pops. Love You. Shawn.

Saturday Morning: The Library

Shawn: Did you see a piece of paper with writing on it? … like a letter?

Librarian: (Curtly, not looking up from her desk.) No.

Shawn: I was in here after work last night trynna do my homework, and wrote the letter, and now I can’t find it.

Librarian: (Still not looking up.) Why don’t you check around the table where you always work.

Shawn: Where’s the maps of Ireland. They say my grandfather might have to go back there even though he doesn’t want to.

Librarian: (Still looking down. Staccato.) Geography. Under Great Britain.

Shawn: (With an angry edge.) It’s not in Britain.

Librarian: (Looking up.) Yes, It is. Aisle 4, Shelves 10 through 17. Clearly labeled Great Britain including Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Shawn: (Pointing to the green tattoo on his forearm) Just remember, 26 Plus 6 equals ONE.

Librarian: (Loudly, Pointing Finger at Shawn.) Quiet.

Shawn: (Louder.) No!

Franklinville High School

I had already found the letter on the floor in the back of the classroom while grading papers and cleaning the room on Friday evening. That’s when I read the letter and realized that Shawn must have dropped it that day during class. Shawn was new in our school. His body language was terse. He seemed beaten and bent inward. He refused to make eye contact. He never talked in class. When I asked him why he slept on his desk everyday, he said that he worked most nights and that he was exhausted all day. That’s all I knew about Shawn. But then, I looked at the address on his file and recognized that the neighborhood where Shawn lived was near the block where my grandfather owned a bar many decades ago. Jimmy’s Pub opened at 7 in the morning for guys coming off the night shift at the Stetson factory and for other graveyard workers. And some 7 a.m. drinkers were guys on their way out to jobs they hated in center city offices and, then, there were the guys who had been out all night drinking and wanted one last shot before they did their daily perish. Cousins right off the boat from Ireland lived above the bar. I worked there while I was going to college. It was a hole of a place where I learned the codes of the Belfast streets thousands of miles away, streets that I’d never actually seen. I could imagine Shawn’s grandfather, his aunt and the way that prison must have shaken them up and spit them out emotional wrecks fractured by fear, frustration and anger, fractured people living fractured lives.

Over the weekend, I read the letter over and over and wondered how Shawn would feel about my seeing his message to his grandfather. I put it in an envelope and wrote a simple note, “Found on Floor of Classroom” and, then, I noticed that I had planned for our class had to read Modern writers like Langston Hughes and James Joyce. So, I decided to begin on Monday with with a meditation. I planned for us to read the Langston Hughes poem that begins, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

Before class, when I gave the envelope to Shawn, he tore it open and sat down immediately in one of the desks at the front, disclosing the letter’s folds and smoothing out the page while he read it, running his fingers along each line as he read. Class started and he looked at me and I smiled at him hoping to silently say, “yes,” with the smile, yes, I read the letter. Shawn hesitated, looked down, then looked up again and smiled back, nodding. Then, I handed out a worksheet asking the entire class to meditate on the lines that Langston Hughes wrote as a young poet, traveling along the Mississippi River in a train headed South:

“I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

I played the music that the jazz musician, Gary Bartz composed to accompany the Hughes poem. I asked just one question beneath the poem’s lines.

“As you read, how do you connect the poet’s rivers to his soul?”

After class:

Shawn: Mister, thanks for finding the letter.

Me: I felt lucky to read it, Shawn.

Shawn: I’m not sending it cuz I just learned that my granda is going to the prison’s hospice which means that he’s very sick.

Me: (Pausing, lump in throat.) He must be very proud of you. I think you should send it to him or give it to him when you visit.

Shawn: I ain’t got the time or the money.

Me: Still, he must be proud of you.

Shawn: I don’t know if they’re gonna send him back to Ireland or keep him here cuz he’s so sick. My aunt told me about this hospice thing on Friday night when she visited from the convent in Allentown where she works.

Me: The worst part must be not knowing what’s gong to happen, right?

Shawn: (Crying, as he looked away as if he were seeing the far shore of a river through his tears, and quoting the poem.) And My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Me: It’s quite a poem, Shawn.

Shawn: I’ll think about it at work. It’s really good.

Me: Don’t forget your homework. (Smiling, ironically).

Shawn: I never forget my homework. (Smiling back, ironically).

Homework

Translate the following passage from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake into your own words. Remember that this excerpt is taken from the end of Anna Livia Plurabelle’s section of Joyce’s novel. Hint: The River Liffey is the scene of this passage, all of which occurs not during the day but at night deep in the language of a very long dream about all rivers.

Monday Evening: The Library

Shawn: Do you wanna hear my homework?

Librarian: I’m busy. Don’t you work today?

Shawn: I skipped work to do my homework first then walk up to the Wal-Mart parking lot to be on the river for a minute.

Librarian: (Smiling). Aren’t you very organized, Shawn?

Shawn: This guy from Dublin’s book is all rivers. You wanna hear my translation of his story about rivers?

Librarian: Yes. But quietly.

Shawn: I’ll whisper it. It’s even better that way.

Librarian: You are a very strange young man. Have you been told this?

Shawn: (whispering)

I can barely hear you with the waters of the river.

The waters chitter. The bats flitter.

Are you not going home alone?

Think of the waters of the River Liffey in Dublin?

Think of the waters of Lough Neagh near Belfast?

I feel as old as that Elm Tree over there.

This is Shawn’s story. This is Seamus’s story.

Good Night, Grand farther, the farther away you go.

Shawn means John.

Seamus means James.

Who were John and James sons or daughters of?

Goodnight, Pops.

Tell me another story about plants and rocks.

Please tell me.

Beside the waters, there hither like the Delaware River.

There thither like the Liffey, the Shannon, the River Erne,

The River Boyne, The River Foyle.

Now, I’m with you beside the rivering waters

The hitherandthithering waters of

Goodnight ……..

Librarian: (Looking up, mouth open in astonishment.) And you wrote that based on the passage in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake?

Shawn: (Nodding. Smiling. Agitated). And now I have to get over to the Wal-Mart parking lot to listen to see the river and tell it what I can hear and telepath it all to my granda who’s up north waiting for the words to echo their way up and back to him.

Librarian: You seem relieved.

Shawn: Of course, it’s sad but I have to say good bye.

(Above) Clinton Cahill’s exhibition “Illuminating the Wake,” which are Cahill’s interpretive drawings on the text of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, synthesizing his encounters with the novel’s dreamscapes. Taken from the web site of the James Joyce Centre in Dublin (https://jamesjoyce.ie/illuminating-the-wake-no-31/).

(Above) Image from web site of Monica and Tyler Aiello’s gallery exhibition titled, “I’ve known Rivers,” which are images based upon the poetry of Langston Hughes (http://www.studioaiello.net/).

*All persons mentioned in this story are fictional (and bear no connectin to actual, historical persons) with the exception of Langston Hughes and James Joyce. All places, also, with the exception of the Wal-Mart parking lot overlooking the Delaware River also are fictional.

(Below) Youtube Musical Composition by Gary Bartz, based upon Langston Hughes’ poetic lines, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opium Confessions on a SEPTA Bus*

At back of a City Bus, In A blur, Emmet Poorboy slumps against a window in prison browns rolled-up sleeve revealing an Irish flag.

Emmet: Mom. It's Emmet. Listen I'm calling cuz I was in this group at counseling today and we got talking about child abuse and I realized you really abused me when I was a kid.

Trish, the ghost of an out queer former drug dealer, is speaking to Thomas De Quincey, the author of the Opium Confessions (1819). They entered the bus at the 30th Street stop as it heads away from Center City and into the vast array of neighborhoods on the North Side. The ghosts enter and position themselves respectively on seat in front of and behind Emmet as he speaks into his cell phone.

Trish: No! D-bone. The answer is No. I’m tired of being set up.

De Quincey: Can you not consider forgiving him? (Gesturing toward Emmet)

Trish: I told you, No!

Emmet: Ma, remember the times when you slammed my head against the table or beat me up in the hall? It hurt and it made me so angry.

Trish: (droning) He stands over my almost lifeless body and empties the rest of the clip into my head! So , then, he does five and a half years up state, and starts frontin that he’s the victim of the cops who arrested him, the guards, his lawyer, the chaplain, the teacher at the prison school, the whole system. But tell me this, ‘How is he a victim?” When he shot me for money, I kinna felt like the vicitim. And I guess now, he’s trynna guilt his own ma? Tell you what, chump, Imma say a Hail Mary for you. (to DeQunicey) How can you even bring me here?

Emmet: But here's the thing. Here's the reason why I was angry. I knew that you were under a lot of pressure and that Pat was threatening you and that the situation was bad. So, I wasn't really mad at you for beating me.

Trish: I writhed in pain at his feet before he blew the final five holes in my head. D-bone, he not only turned out the lights, he robbed me of one last glance at my junkie mom strapping up under the el, one last, sweet good bye kiss for Kathy’s cheek, one last breath of Philly air wafting off the Delaware. He stole my life, D. That’s so grimy.

De Quincey: I importune you, Listen, Trish.

Emmet: And I wasn’t mad at Pat for forcing me to do those things. You know what I mean, mom. For god’s sake I was only ten years old.

Trish: (to the thin air, lamenting what she’s hearing) What?

Emmet: What I was mad at you for was your taking the situation out on me. I was mad at you for not dealing with Pat. I didn't deserve that mom, and I knew that you didn't deserve that either.

Trish: (Speechless. Gazing into space, affect: astonished as if something has just occurred to her).

De Q: Do you hear what he is saying?

Trish: How can I not get this?

Emmet: So, now it just doesn't make sense to me. It seems like you've just given up, and I wanted to tell you that, I really believe that you're better than that.

Trish: You know, DeQuincey, I wish I coulda said that to my old lady.

De Q: you still can, Trish.

Emmet: You know how if we meet downtown. You always say you like McDonald's and how we should just eat there? I think we should go someplace better. I think that you're better than that. Can we do that sometime? Tommy can afford to give you 50 bucks or whatever. You're worth that, ya know.

Trish: (to audience, shaking head in wonder) Ladies and Gentlemen! Emmet Poorboy, Philadelphia’s finest Philosopher.

Emmmet: I actually think that you should get a restraining order against Tommy. Or .... Do something. I want you to take care of yourself. Ya know?

Trish: (again, to the audience) We can assume that Tommy is ma’s latest unforgiving brute.

De Q: (softly.) Trish. What must you be thinking?

Trish: (reflective tone.) Thomas De Quincey, I must be thinking that, when Emmet Poorboy, professional beast, was a ten-year-old abused child that he must have been an innocent, precious, sensitive being. Emmet Patrick Poorboy must have been an angel in his own way.

De Q: (Pleading) How can you not consider forgiving, Trish? For you? For your hell-bent mother? For the Emmet that was once an innocent?

Trish: (Expressing doubt, shaking her head at DeQuincey, looking at audience.) Well, I don’t know about all that.

Emmet: Aright, mom, I'll talk to you later.

Trish: (Speaking to Emmet) Emmet, imma tell you what you just told your mom. (Quoting Emmet’s cell-phone conversation.) I think we should go someplace better. I think that you're better than that. Can we do that some time? (Pauses. Gazing Ironically at Emmet.) You're worth that, ya know.

De Q: Are you saying you forgive him Trish?

Trish: I forgave him thirty years ago when his mom abandoned him with that creep, Pat. I forgave him twenty minutes ago when you told me to “be silent and hearken to this little lamb’s lament.”

De Q: I honor you as my muse, Trish.

Trish: Save the nostalgic longing for your Sweet Paula whose essence hovers on the mists of the River Thames, D. I gotta bounce.

De Q: is your own mother languishing in a heroin haze somewhere under the el, looking just slightly more like a ghost than you or I?

Trish: (Quoting Emmet, again. Ironic Tone.) You know how if we meet downtown. You always say you like McDonald's and how we should just eat there? I think we should go someplace better. I think that you're better than that. Can we do that sometime? Tommy can afford to give you 50 bucks or whatever. [Pauses, looks again at audience] You're worth that, ya know.

De Q: This is farewell, Trish.

Trish: Away, to England, D-Bone. (Halts and Kisses Emmet’s forehead.) Emmet, my precious child. I have an errand for both of us .

I have a junkie to find before dawn when she starts looking for another fix.

Imma tell her, (holding a fake cell phone to her face) we gotta find a better place.

(Now Imitating Emmet’s manner.) Ma, I think that you're better than that. Can we do that sometime? You're worth that, ya know. Aright, mom, I'll talk to you later.

*All of the characters in this play are fictitious and bear no relation to personages, living or dead, with the exception of Thomas DeQuincey who just over two-hundred years ago began his journey back from the delirium of opium addiction.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bon Bon, Jan Savitt, and me*

Photo from Vol Vistu Gaily Star (1939).

See author’s reading of story in audio file at bottom. Also, Recording of Bon Bon performing “The Masquerade is Over.”

I found an envelope on my desk full of letters that I must have written back in brighter times. This one was on top.

Dear Bon Bon:

I hope that’s OK, --to call you “Bon Bon.” I met you in 1974, the year just before you passed. You had invited my dad to visit, and he brought me along. I was 19. All I knew was that you were the crooner whose silken voice fronted the Jan Savitt Orchestra in the 1930s when my dad was a trombone player with the band.

Big handshakes when we arrived. I think you had been ill, and you were staying in Philly with your sister or an aunt. Trying to seem grown, I said, “Bon Bon, it’s great to meet you.” But my dad cut me down, saying, “That's Mr. Tunnell, to you, boy. Who do you think you are?” So, I corrected myself, “Sorry, Mr. Tunnell.” And you smiled and said, “Don’t pay that old goat no mind.” And then you candidly asked my dad, “Jack, does he play?” And my dad said, “He’s terrible.”

The room had an audience of three or four of your cousins and a blind lady from the neighborhood. There was also a delicate young woman about my age, a niece. My dad was being very courteous and fun with everybody, except me, of course. He usually reserved his jovial laugh, and decorous, joking manner for people whom he wished to impress. I was easily embarrassed in those days, particularly in “company” with my father. The reason was that my dad’s way of dealing with me was to attack when he sensed my weakness. The worst was when we were with other people.

So then, my father dressed me down again with a rebuke, “Kid, when are you gonna get a lip?” Shaking his head, he lamented loudly that I never practiced. But, Bon Bon, you put your arm around me, and whispered in a tone that the whole room could hear, “Young fella, your old man ain’t never gonna change. He’s just wound up too tight. I would love to hear you playing or even leading a band somewhere, someday. I know you will.” You were speaking like you could look into my future. Then, you quipped, “You gotta have a sweet-lookin’ trumpet or a trombone, right?” I nodded. That was a lie. And you included my dad in the musing, “Jack, we gonna buy this kid a valve-trombone like that silver-plated horn we bought for you. Remember that, Jack? I told Mr. Savitt to get that one for you! You always made it sing.”

Bob Bon! The airy way you intoned your words was a melody. Your speaking voice rose and fell like a brass choir. Your phrasing, your pauses weren’t just talk, your way of speaking was like Coltrane and Miles trading licks at a jam session. While speaking, you walked me across the room and introduced me to your niece, and she greeted me with this kind, innocent, bashful, welcoming single syllable and accompanying gesture, “Hi.” She raised her hand faintly and tapped the air twice delicately. I melted. You prompted me,

“Well, is it trombone or trumpet? I know Tommy Dorsey here would never let you play the sax." My dad rebutted, “Don’t mix me up with that scoundrel, Dorsey!” For my part, I was way off key at this point and, trying to sound mature and to join in the banter, I overstated my cause, “I play both! I play trombone and trumpet. Man, I’m bad.”

You saved me, halting and gazing at my old man, warning him, “Look out, Jack. He’s coming’ for you.” My dad just shook his head.

We were in the nice room at the front of your folks’ house where visitors came. When my mom and dad had been together, we had had a room like that. Drinks appeared. There was a lot of laughing. Once I started to feel the beer, I was OK. That’s how I met you. You were more than generous. You were a magnanimous presence. Well, the story continues. My dad and I left your family high and late that pallid summer afternoon. It was the seventies in Philly. The car radio played Temple University’s Jazz Station low, and against a background of static another friend of my dad, Hank Mobley, was wafting a Brazilian-styled Bossa melody from the car’s speakers. We were somewhere in Southwest Philadelphia. As we drove away, we were euphoric on so many memories you and my father shared. Skying on that feeling of friendship, --free associating like a long piano solo. We were inebriated by the luxury of having been together partying with good people. For the moment, I was drunk. And so I felt almost safe. Dad was telling me stories about you guys. I knew that you were the star of Philly’s Jan Savitt Orchestra. As my father wheeled his rusting Cadillac homeward, he told me that you were Catholic and that, while playing a gig in Pittsburgh where the band had to stay in a hotel, he met you early one Sunday morning walking to mass at a nearby Catholic church. He reminisced over the steering wheel, “It was a big band. Fifty people or more on the road. But that singled Bon Bon and me out. We were the only two practicing Catholics. After that, we prayed together when the band was on the road on weekends.” It wasn’t just the whiskey talking, it was affection. From my dad, that was different. His voice went falsetto high and even broke a couple of times. He said you had “credibility” with Jan Savitt and that the bandleader followed your advice about musical arrangements, style and orchestra personnel. After you and my dad had gone to church together, you must have commended his trombone playing to Savitt. So, the conductor began calling him up during performances from the back of the bandstand to the mike. Once up front, my dad said that he would crochet vamps and runs on the trombone behind “Bon Bon’s magical manner of lyricizing.” His horn had to echo your singing. The trombone had to blend, dipping in and out of your trademark sound. My dad concluded, “That was a great opportunity. Bon Bon opened the door for me.”

So, after leaving hotels in Reading and Scranton, Pennsylvania and Atlantic City and Cape May, New Jersey to seek out Sunday morning masses, doors started opening for my dad. I guess no matter how much hell you guys were raising through Saturday nights, you both went regularly together to communion the next morning. You had a bond. I learned that you knew lots of people in Pittsburgh, too. Through you, my dad met Art Blakey, Sonny Stitt and Ahmad Jamal all playing in the Hill District. “Bon Bon brought me to the party,” my dad remembered.

That suave evening on the way home, I also learned that Jan Savitt was real committed to launching an integrated orchestra back in the 1930s. As if teaching, my dad historicized, “Savitt was Jewish and he had seen too much hate. He wanted music to be a language that everybody could hear and speak and understand.” I was young, but I got that.

My dad remembered that, in some bands, white players were paid higher, belonged to separate musicians’ unions than black players and, “There were places we played where we had to enter through separate doors because the owners were racist idiots. It was humiliating to everybody. You see. You’ve got a friend who is including you in his life. You’ve got a friend who’s sharing his family and connections with you. You’ve got a friend who is taking care of you. Then, you see him being excluded from the money and the respect he deserves, and there’s nothing you can do about it. His family and friends always made space for me, --always were good to others. I was never cut out. No matter how hard he worked, Bon Bon was exploited, disrespected and insulted. He always showed courage. He always showed humanity.”

The way home, punctuated by neighborhoods and stop lights and crosstown expressways, went quiet. Finally, my dad asked me, “So, what do you think?” Feeling unprepared, I said, “I don’t know,” Then, he reprimanded, “Well you’d better figure it the hell out, kid. You’d better figure things out or you’re going be stuck out in the cold.”

We were back to being bitter. My dad by invective. Me by clenched silences. The stress of being with my dad made me sweat so much that I felt feverish. The hot summer evening suddenly seemed cold. So much had happened, I couldn’t make sense of the currents sweeping through my shaking body. I got out of the car finally and my dad didn’t say “Bye,” he just said, “Figure it out!” That was over half-a-century ago, but since that time whenever I wanted to cheer my father up, I would mention your name. Especially at the end of his fight with cancer. As he’d lay listless in the aftermath of treatments, all I had to do was mention you if I wanted to see him pause and smile. Bon Bon! However briefly, you brought me and my dad together. You made us whole. Yes. Your voice called friends and families and lovers to life’s weird party. Then, you sang, and those people felt the love. Audiences that came to hear you saw Black people and Jewish people and Irish Catholics and Protestants and Muslims all performing together back in the 1930s. You were a healer.

My dad was cruel, and I’ve had to deal with that. But he did love you. And the best gift he gave to me was the way he adored jazz musicians for their talents and their friendship.

He told me, “You can learn to love Jazz. It’s African music. It’s beautiful. Jazz is like being part of a big family. Ella and Dizzy and the Duke and the Count. They’re all connected. But you can never know what Black people in this country experience. You can never know the bigotry they have to face. You can’t know that from the inside.”

I got that as a kid. The only time I had ever seen the old man cry was near dinnertime on the day in July 1971 when Louis Armstrong died. I was just home from my job at a shoe factory in Norristown and was nursing a beer on my dad’s couch when the evening news suddenly reported that the Great Satchmo had passed. His face went wet with tears. “That man never played a bad note,” was all he could say, over and over, like a mantra.

Bon Bon! What I learned was that music --even the crooked notes like what I played on my student model trumpet at weddings and dances and other weekend gigs-- still had power over people.

So, no matter how angry I felt about my dad’s abuses to my mom or his bitter way with me, I have to thank you for caring. Even for that skinny, frightened teenager I was. You made me want to play bell tones and to share my sound. I wanted to soar on that silver valve-trombone that you and Jan Savitt bought for my dad. That was a goal, right? Well, even though my learning curve has been a spiritual mudslide, I feel your charm in moments of reverie like today writing this letter. I listen to you croon “The Masquerade is Over,” and I hear your voice honor love. I learned that, --at least. No matter whatever else has happened.

When the weather breaks, I’m going to be tracking down where you’re buried. I’m quite sure that must be somewhere in Pennsylvania. My dad once said that he would have loved to visit with a wreath from the two of us, --to remember you. I just want you to know all these years later that your voice is still heard, Mr. Tunnell.

With Affection,

Johnny

* All of the persons named in this story are completely fabricated and fictitious and bear no connection to actual persons living or deceased, --except for Jan Savitt, George “Bon Bon” Tunnell, Ella Fitgerald, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Stan Getz, Ahmad Jamal, Art Blakey, Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

youtube

youtube

#Jazz#Philadelphia Jazz#American History#African American#Religion#History#Jan Savitt#Louis Armstrong#George Bon Bon Tunnell

0 notes

Text

Suspended Lives, Inspired Art

If you see Dulce N. Ramirez’s piñata image (photo fragment above), you may never return to who you were before you saw it. You will know your humanity in a new way.

Her art will change you. As will all nine of the journeys recounted in the innovative, genre-busting exhibition now on display at Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens (1020 South Street) until October 18th.

To prepare for the courage with which these Latinx geniuses have reclaimed the piñata form to restore human warmth to the coldness and horror of their lives crossing borders, you should listen to their recorded accounts (in Spanish and English) posted online by Puentes de Salud, their sposnoring organization:

http://www.puentesdesalud.org/vidas-suspendidas/

There, as in the exhibit, you will know Dulce’s encounter with grief and loss. She tells her story with eloquence and candor, --with the same freshness that she has imbued in clay tones intimated in her sculpture.

Yes. When you see her papier-mâché images in three dimensions, when you stand before her work, you will know the kindness and wisdom with which Dulce’s delicate craft has told her story. You will note the attention she has paid to hands, and to the bent abnegating posture of a parent turning away from the child embodied there.

Dulce’s artwork brings back the humanity placed at risk by her brutal encounter with systems in the United States. Those systems consistently abandoned her. Thus, we find a unique form of grace, profoundly embedded in the trauma that she has called up from early experiences of abuse and at other formative moments of her childhood.

Dulce has chosen creative action over the stultifying silence.

This project was founded and coordinated by Nora Hiriart Litz, director for Art and Culture at Puentes de Salud. She is both artist and teacher. Given the dynamic spaces that she has collaborated in creating with these nine exhibitors, one needs also to stand in awe of Nora Hiriart Litz’s sensitivity for dialogue. Her conversations with the artists have inspired their conversations with the images that they have crafted for us, in turn, to meet and to know at a profound level. Because ..... There in these images, we meet ourselves, our opportunities to embrace our humanity, --instead of turning away.

Puentes de Salud (Bridges of Health) is an organization that promotes the health and wellness of Philadelphia’s rapidly growing Latinx immigrant community through advocacy for health care, innovative educational programs, and community building.

Dulce N. tells the story. Hers is a tale of creation. Her commitment as an inspired artist is to bring to her own child the openness, attentive love and kind reception that was denied to her as a child, as an adolescent and as a young adult. Hers is a choice that blesses all who see the installation with the same life force that one encounters at our Rodin Museum or in the creation myths of Mexico’s Popul Vuh.

I was Dulce’s English teacher at Kensington High School in the years immediately following her arrival in Philadelphia from Mexico. So, I witnessed her longing as a student to grow intellectually. I saw her searching for places and occasions to realize her abilities as an artist. And now, I can write about her as a talented leader and, most importantly, as an ethical and gentle force in family and community. Her journey to reach this moment has been a long and tortuous path. Her determination to pursue these accomplishments has, as long as I have known her, been based in a commitment to give the world empathy wherever it has given her grief. We owe Dulce Ramirez and her fellow artists as well as their teacher, Nora Hiriart Litz, a vote of gratitude for showing us the meaning of our humanity, the meaning of community.

0 notes

Text

Shawn’s Story*

Shawn’s fable unfolds along the banks of the rivers that authors, Langston Hughes and James Joyce traveled. Also, here to be found is the River Delaware as it flows through Philadelphia and environs. Among other themes, this is a tale of incarceration and deportation. Waiting at the story’s edges, readers will notice that we also meet with a lot of homework, –and a very discerning librarian.

(Above) Image Taken from Salmon Ireland’s web site (Salmonireland.com), is a landscape photograph of the River Foyle.

The Letter

Hi Pops, thanks for your letter. Too bad, the prison blocked a lotta words out. What I got was that you’re getting to go out with work crews to pick up trash on the highways. It must be weird being chained together like that and having guards with shotguns and such watch over you guys while you’re just basically cleaning the roadside. I really like the part where you said that you all go up to the highway right next to the river and that you always take a minute from sweepin or whatever to look out over the riverwaves and see the sun reflect on the swelling banks and feel the breeze. So, that was a really good idea where you said if after work some day I walk to the far end of the Wal-Mart parking lot on Delaware Avenue where it comes up on the river that I’ll be looking out over the same Delaware River as you seen earlier, and I’ll be seeing the same waves, and the same currents, and the same mists and breezes playing off the wave- tops, hearin the same sounds and tasting that little bit of sea salt that the river has from its trip out to the ocean. Imma do it. I miss you, Pops. If I go down that parking lot where it looks across to Camden on the opposite bank on the same day maybe when y’all been out on the highway cleanup crew in your orange prison suits, I’ll be able to catch up with your spirit, at least. And, I’ll say all the stuff you used to listen to me carrying on about. How muad I get at everything and how sad and sorry I feel about other stuff. Remember? I ain’t seen Mom or Dad at all for a long time. But Aunt Helen came down from the convent last week and helped me clean the place. So, we scoured the joint from “stem to stern” just like you always used to say. “FROM STEM TO STERN.” I kept repeating that and then Aunt Helen and me was laughing about the way you used to say it and about how you talk and your Irish accent, “From Stem To Stern,” like a pirate or something. Haha. Don’t get mad. I miss you. Pops. Love You. Shawn.

Saturday Morning: The Library

Shawn: Did you see a piece of paper with writing on it? … like a letter?

Librarian: (Curtly, not looking up from her desk.) No.

Shawn: I was in here after work last night trynna do my homework, and wrote the letter, and now I can’t find it.

Librarian: (Still not looking up.) Why don’t you check around the table where you always work.

Shawn: Where’s the maps of Ireland. They say my grandfather might have to go back there even though he doesn’t want to.

Librarian: (Still looking down. Staccato.) Geography. Under Great Britain.

Shawn: (With an angry edge.) It’s not in Britain.

Librarian: (Looking up.) Yes, It is. Aisle 4, Shelves 10 through 17. Clearly labeled Great Britain including Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Shawn: (Pointing to the green tattoo on his forearm) Just remember, 26 Plus 6 equals ONE.

Librarian: (Loudly, Pointing Finger at Shawn.) Quiet.

Shawn: (Louder.) No!

Franklinville High School

I had already found the letter on the floor in the back of the classroom while grading papers and cleaning the room on Friday evening. That’s when I read the letter and realized that Shawn must have dropped it that day during class. Shawn was new in our school. His body language was terse. He seemed beaten and bent inward. He refused to make eye contact. He never talked in class. When I asked him why he slept on his desk everyday, he said that he worked most nights and that he was exhausted all day. That’s all I knew about Shawn. But then, I looked at the address on his file and recognized that the neighborhood where Shawn lived was near the block where my grandfather owned a bar many decades ago. Jimmy’s Pub opened at 7 in the morning for guys coming off the night shift at the Stetson factory and for other graveyard workers. And some 7 a.m. drinkers were guys on their way out to jobs they hated in center city offices and, then, there were the guys who had been out all night drinking and wanted one last shot before they did their daily perish. Cousins right off the boat from Ireland lived above the bar. I worked there while I was going to college. It was a hole of a place where I learned the codes of the Belfast streets thousands of miles away, streets that I’d never actually seen. I could imagine Shawn’s grandfather, his aunt and the way that prison must have shaken them up and spit them out emotional wrecks fractured by fear, frustration and anger, fractured people living fractured lives.

Over the weekend, I read the letter over and over and wondered how Shawn would feel about my seeing his message to his grandfather. I put it in an envelope and wrote a simple note, “Found on Floor of Classroom” and, then, I noticed that I had planned for our class had to read Modern writers like Langston Hughes and James Joyce. So, I decided to begin on Monday with with a meditation. I planned for us to read the Langston Hughes poem that begins, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

Before class, when I gave the envelope to Shawn, he tore it open and sat down immediately in one of the desks at the front, disclosing the letter’s folds and smoothing out the page while he read it, running his fingers along each line as he read. Class started and he looked at me and I smiled at him hoping to silently say, “yes,” with the smile, yes, I read the letter. Shawn hesitated, looked down, then looked up again and smiled back, nodding. Then, I handed out a worksheet asking the entire class to meditate on the lines that Langston Hughes wrote as a young poet, traveling along the Mississippi River in a train headed South:

“I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

I played the music that the jazz musician, Gary Bartz composed to accompany the Hughes poem. I asked just one question beneath the poem’s lines.

“As you read, how do you connect the poet’s rivers to his soul?”

After class:

Shawn: Mister, thanks for finding the letter.

Me: I felt lucky to read it, Shawn.

Shawn: I’m not sending it cuz I just learned that my granda is going to the prison’s hospice which means that he’s very sick.

Me: (Pausing, lump in throat.) He must be very proud of you. I think you should send it to him or give it to him when you visit.

Shawn: I ain’t got the time or the money.

Me: Still, he must be proud of you.

Shawn: I don’t know if they’re gonna send him back to Ireland or keep him here cuz he’s so sick. My aunt told me about this hospice thing on Friday night when she visited from the convent in Allentown where she works.

Me: The worst part must be not knowing what’s gong to happen, right?

Shawn: (Crying, as he looked away as if he were seeing the far shore of a river through his tears, and quoting the poem.) And My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Me: It’s quite a poem, Shawn.

Shawn: I’ll think about it at work. It’s really good.

Me: Don’t forget your homework. (Smiling, ironically).

Shawn: I never forget my homework. (Smiling back, ironically).

Homework

Translate the following passage from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake into your own words. Remember that this excerpt is taken from the end of Anna Livia Plurabelle’s section of Joyce’s novel. Hint: The River Liffey is the scene of this passage, all of which occurs not during the day but at night deep in the language of a very long dream about all rivers.

Monday Evening: The Library

Shawn: Do you wanna hear my homework?

Librarian: I’m busy. Don’t you work today?

Shawn: I skipped work to do my homework first then walk up to the Wal-Mart parking lot to be on the river for a minute.

Librarian: (Smiling). Aren’t you very organized, Shawn?

Shawn: This guy from Dublin’s book is all rivers. You wanna hear my translation of his story about rivers?

Librarian: Yes. But quietly.

Shawn: I’ll whisper it. It’s even better that way.

Librarian: You are a very strange young man. Have you been told this?

Shawn: (whispering)

I can barely hear you with the waters of the river.

The waters chitter. The bats flitter.

Are you not going home alone?

Think of the waters of the River Liffey in Dublin?

Think of the waters of Lough Neagh near Belfast?

I feel as old as that Elm Tree over there.

This is Shawn’s story. This is Seamus’s story.

Good Night, Grand farther, the farther away you go.

Shawn means John.

Seamus means James.

Who were John and James sons or daughters of?

Goodnight, Pops.

Tell me another story about plants and rocks.

Please tell me.

Beside the waters, there hither like the Delaware River.

There thither like the Liffey, the Shannon, the River Erne,

The River Boyne, The River Foyle.

Now, I’m with you beside the rivering waters

The hitherandthithering waters of

Goodnight ……..

Librarian: (Looking up, mouth open in astonishment.) And you wrote that based on the passage in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake?

Shawn: (Nodding. Smiling. Agitated). And now I have to get over to the Wal-Mart parking lot to listen to see the river and tell it what I can hear and telepath it all to my granda who’s up north waiting for the words to echo their way up and back to him.

Librarian: You seem relieved.

Shawn: Of course, it’s sad but I have to say good bye.

(Above) Clinton Cahill’s exhibition “Illuminating the Wake,” which are Cahill’s interpretive drawings on the text of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, synthesizing his encounters with the novel’s dreamscapes. Taken from the web site of the James Joyce Centre in Dublin (https://jamesjoyce.ie/illuminating-the-wake-no-31/).

(Above) Image from web site of Monica and Tyler Aiello’s gallery exhibition titled, “I’ve known Rivers,” which are images based upon the poetry of Langston Hughes (http://www.studioaiello.net/).

*All persons mentioned in this story are fictional (and bear no connectin to actual, historical persons) with the exception of Langston Hughes and James Joyce. All places, also, with the exception of the Wal-Mart parking lot overlooking the Delaware River also are fictional.

(Below) Youtube Musical Composition by Gary Bartz, based upon Langston Hughes’ poetic lines, “I’ve Known Rivers.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wilner’s Epiphany

Edwidge Danticat (below) is author of The Farming of the Bones, a narrative whose traumatic events resolve in a woman endowing her people’s lives with meaning by knowing and saying their names after they have gone and the stories that their names inspire.

Edwidge Danticat’s books create safe spaces for students to share their trauma.

Wilner’s Dream*

The dream repeats. Every time, Wilner wakes up, his soul trembling. Angry. Frightened. Disoriented. It’s always Friday night. He’s 12-years-old again. He’s with his grandmother. She’s signing to him. He’s signing back. She has her cheque from her job cleaning offices in center city. They’re in the line for the teller at the bank. Grandmother gestures and tries to say the words in Kreyol. She makes sounds that she cannot hear. Wilner is signing back that he has the list of stuff they have to buy at the market and that he knows there’s not much time to do the shopping and to return home to prepare the meal. Then, Wilner hears the man in line behind them complaining aloud, “I wish these damn deaf people would stop their damn grunting like damn animals. They’re a disgrace.” Wilner feels it like he’s been punched hard in the stomach. He turns to the man and retorts loudly and clearly, “Mister, why would you even say that!” The man’s eyes stare blankly, then his face flushes pink, and he goes defensive. Fingerpointing back, he hollers, “Son, I wasn’t talking to you.”

The heavily armed bank security guard struts up to the man. Wilner’s grandmother, feeling confused, is signing questions about the guard and the man to Wilner. The security guard asks the man if Wilner is making trouble, and the man is pointing his stubby finger alternatively at Wilner and at his Grandmother and telling the guard that “he’s a rude boy” and that his grandmother is “incompetent and shouldn’t be allowed to wander around like this.” The man’s body is heavy and wheezes and gasps for breath whenever he says something. He acts like a drowning victim abruptly swallowing the air. The man pauses and gasps after every insult, after every threat a deep breath, and after every charge to the security guard, he gulps.

That’s when the dream goes fever-pitch. That’s when Wilner sees red in his sleep. He always wakes up perspiring profusely and scared that he’s been thrown to the ground, handcuffed, and arrested. Dragged away by the police. He always wakes up frightened that his grandmother is lost somewhere, crying, moaning and distracted to the point of delirium and not able to understand where she is or what has happened. Wilner feels the terror that comes with anger, fear and confusion. He’s awake now. He blinks. He is not in prison. Did he hurt the man? Pause. No. Grandmother passed two years ago. Wilner feels his face.No bruises. He’s in his room. Sigh. Relief. Finally, a moment’s calm.

Wilner’s Epiphany

In the hallway on my way to class.

Wilner: Mister, I have made a discovery.

Me: Wilner, I can’t be late? Are you OK?

Wilner: No. I have made a discovery.

Me: Can you tell me before class tomorrow?

Wilner: But no. This is very important.

Class bell rings.

Me: (Resigned to being late, again.) My goodness, what have you discovered?

Wilner: (Making fun of my way of speaking.) My goodness, it’s Alexander Graham Bell. He wasn’t trying to invent the telephone. He was trying to invent a hearing aid. (He Smiles.)

I congratulate Wilner on his discovery and run to class. Later, Wilner comes by and explains to me that he originally wanted to write an essay for our class on the history and origins of his cell phone. I didn’t know much about Wilner. I did remember that he had wanted to write about the technology of his cell phone. I also knew that he had a habit of speaking very carefully, as if each statement were a kind of mindfully conceived thesis. When Wilner began researching by reading online about Alexander Graham Bell, to whom the invention of the telephone is attributed, Wilner learned that Bell had been an advocate for the hearing impaired. Bell had been experimenting with tiny electric speakers to amplify sound within the ear. When Wilner realized that Bell was impassioned to improve the lives of deaf people because members of Bell’s family struggled with hearing problems, Wilner felt that the fates were speaking to him. Wilner explained that his own grandmother and his sister both had experienced hearing problems.

Wilner: Mister, I learned something that I had not planned to learn.

Me: Wlll you change your topic to Bell’s invention of hearing aids?

Wilner: But no. I want to write about how when a person plans to learn one thing, he can end up learning other, unexpected things.

Me: Wil, I’ve noticed that you speak several languages. How many languages do you speak?

Wilner: (Counting on his fingers.) Kreyol from Haiti and home. French from school in Haiti. Spanish from when we lived in the Dominical Republic. English from here. Sign language all my life.

Me: How did you do it? How did you learn so many languages?

Wilner: I had to. (Reflecting.) To survive.

Me: Did Bell need to invent a telephone or a hearing aid? Was there a necessity that drove him to invent?

Wilner: (With respectful frustration.) If you’re saying that “Necessity is the mother of invention,” that would be a gross cliche. I’m saying the opposite. No one can control what they will learn. What we learn in life, we very frequently do not intend to learn.

Me: (speechless.)

The Farming of the Bones

That year, Edwidge Danticat’s novel, The Farming of the Bones, came right after our AP Class’s reading of James Joyce’s Dubliners. Wilner seldom spoke in class. Usually, he would wait until the last moment of a conversation to add a confouding question. For example, one day, we had discussed the pathetic qualities of Maria, a character in Joyce’s story, “Clay,” and we had reached the point of examining Maria’s sadness when Wilner entered the discussion to say, “So, the story makes us sad that the old woman’s family betrayed her. I agree. But hasn’t Maria also betrayed her family and us the readers, too? Maria wasn’t the victim you want her to be. She chose to go to her relatives’ party. She chose to work in the laundry where she worked, and she chose to sing the song that made everybody feel sorry for her. For me, she is courageous. She is not a victim. I don’t feel sorry for her. I believe that the author wants the readers to recognize how brave Maria is and how weak-minded people who feel sorry for other people can be. Maria knows that she is deaf and that she misses things. It’s not a fact that you or her family are keeping from her.” Usually, after Wilner’s question or comment, the room would go hush for a while.

On the day that we finished reading The farming of the Bones, a group of students walked into the classroom complaining.

David: Lavin, I’m so mad about tis book. I stayed up late last night to finish it.

Me: Why are you mad?

Vicki: He’s mad because of what Amabelle did?

Ines: (Shaking the book in her hand unhappily.) It was a big disappointment.

We began class before the bell rang that day. Students were conflicted by their feelings for the character, Amabelle, whose life story unifies the novel. She is a Haitian servant in the home of a wealthy Dominican soldier’s family. The story is set against the historical events surrounding the 1937 massacre of Haitians by the Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo’s military. The majority of our class expressed anger with the book because the conclusion surprised them. Their collective condemnation of the Danticat’s novel went as far as Antonio saying, “Lavin, this whole novel was a waste of time because what happened last night or what didn’t happen.” Then, Wilner spoke.

Wilner: (Addressing the entire class.) You know I’m just thinking that I never told anybody in class that I am from Haiti. Like so many of you, I lived in the Dominican Republic, too. So, I know those jokes about Haitians. You might have noticed that I didn’t laugh at them. Last night, you learned something about Amabelle, something that you didn’t expect to learn. Sometimes, you will be thrilled by learning what you didn’t expect. Sometimes, you will be horrified. I was not surprised by how Amabelle’s story ended in last night’s reading. Amabelle lost so much. The River ate her parents and other people in the book. The Dominican Police probably killed her lover, Sebastien. For me, the point was not that she lost those people, the point was that she loved them. Amabelle said all of their names and wanted to remember their lives. For me, Amabelle became all of those people, the people of Haiti who lived and died at that time. For me, they were all very beautiful because Amabelle loved them and tried to take them with her in her broken heart.

Class: (Speechless.)

In the classes after that day, it wasn’t unusual for Eva or Pedro to say, when the conversation reached a lull, “Wil. Tell us, what do you think? One such day, I had asked students to write about a dream that recurs in their lives and how they make sense of it. Several students turned to Wilner, at one point and asked him to read his dream account aloud to the class. Wilner had written about his dream in the third person. When he read from his dream journal, there was silence in the room.

Wilner: . . . . . . He always wakes up perspiring profusely and scared that he’s been thrown to the ground, handcuffed and arrested. Dragged away by the police. He always wakes up frightened that his grandmother is lost somewhere, crying, moaning and distracted to the point of delirium and not able to understand where she is or what has happened. Wilner feels the terror that comes with anger, fear and confusion. He’s awake now. He blinks. He is not in prison. Did he hurt the man? Pause. No. Grandmother passed two years ago. Wilner feels his face.No bruises. He’s in his room. Sigh. Relief. Finally, a moment’s calm.

Class: (Silent.)

Kyle: Wil. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Your story is everyone’s story. (More Silence.)

Kyle: (Looking surprised.)

Kyle, then, began clapping and the whole class joined in applauding, loud enough that the principal wondered from his office what ever can be going on in there.

* All of the personages in this story are fictional fabrications with the exception of Edwidge Danticat whose novels and characters continually teach us lessons that we had not planned to learn.

0 notes

Text

Wilner’s Epiphany

Edwidge Danticat (below) is author of The Farming of the Bones, a narrative whose traumatic events resolve in a woman endowing her people’s lives with meaning by knowing and saying their names after they have gone.

Danticat’s books create settings for students to share their experiences with trauma.

Wilner’s Dream*

The dream repeats. Every time, Wilner wakes up, his soul trembling. Angry. Frightened. Disoriented. It’s always a Friday night. He’s 12-years-old, again. He’s with his grandmother. She’s signing to him. He’s signing back. She has her cheque from her job cleaning offices in center city. They’re in the line for the teller at the bank. Grandmother gestures and tries to say words in Kreyol. She makes sounds. Wilner is signing back that he has the list of stuff for the market and that he knows there’s not much time to buy the food.

Then, Wilner hears the man in line behind them complaining aloud, “I wish these damn deaf people would stop their damn grunting like damn animals. They’re a disgrace.” Wilner feels it like he’s been punched hard in the stomach. He turns and retorts loudly and clearly, “Mister, why would you even say that!” The man goes blank, then his facial skin flushes pink, and he goes defensive. Fingerpointing back, he hollers, “Son, I wasn’t talking to you.”

The heavily armed bank security guard walks over. Wilner’s grandmother is becoming confused. The security officer is asking the man if Wilner is making trouble, and the man is pointing a stubby finger at both Wilner and his grandmother and telling the guard that “he’s a rude boy” and that his grandmother is “incompetent and shouldn’t be allowed to wander around like this.” The man’s body is very heavy and wheezes and gasps for breath whenever he’s said something. He acts like he’s a drowning victim. He pauses to drink in air after every insult, after every threat a deep breath, and after every charge to the security guard, he gulps.

That’s where the dream goes feverish. Wilner sees red in his sleep. He always wakes up perspiring profusely and scared that he’s been thrown onto the ground, handcuffed and arrested. Dragged away to the police station. He always wakes up frightened that his grandmother is lost somewhere crying, moaning and distracted to the point of delirium and not able to understand where she is or what is happening to her. Wilner feels the terror that comes with anger, fear and confusion. He’s awake now. Is he hurt? Did he hurt the man? What year is it? Grandmother passed two years ago. OK. He’s in his room, not a prison. Sigh. Relief. Finally, a moment’s calm.

Wilner’s Epiphany

In the hallway on my way to class.

Wilner: Mister, I have made a discovery.

Me: Wilner, I can’t be late. Are you OK?

Wilner: No. I have made a discovery.

Me: Can you tell me in class, tomorrow?

Wilner: But no. This is very important.

Class Bell Rings.

Me: (Resigned to being late, again.) My goodness, what have you discovered?

Wilner: (Making fun of my way of speaking.) My goodness, it’s Alexander Graham Bell. He wasn’t trying to invent a telephone. He was trying to invent a hearing aid. (Wilner is smiling.)

I congratulate Wilner on his discovery. I run to class. Later, Wilner comes by and explains to me that originally he wanted to write an essay for our class on the history and origins of his cell phone. I didn’t know much about Wilner. I did know that he wanted to write about the technology of his phone. I also knew that he had a habit of speaking very carefully, as if each statement were a kind of mindfully conceived thesis. When Wilner began researching by reading online about Alexander Graham Bell, to whom the discovery of the telephone is attributed, Wilner learned that Bell had been an advocate for the deaf. Bell had been experimenting with electric speakers to amplify sound within the ear. When Wilner realized that Bell’s life in a family of deaf persons was what had motivated Bell, Wilner felt that the fates were speaking to him. Wilner explained to me that his grandmother had been deaf and that his sister was hearing impaired.

Wilner: Mister, I learned something that I had not planned to learn.

Me: Will you change your topic to Bell’s invention of hearing aids.

Wilner: But no. I want to write about how when a person plans to learn one thing, he can end up learning other things.

Me: Wilner. I’ve noticed that you speak several languages. How many languages do you speak?

Wilner: (Counting on his fingers.) Kreyol from Haiti and home. French from school in Haiti. Spanish from when we lived in the Dominican Republic. English from here. Sign Language my whole life.

Me: How did you do it? How did you learn so many languages?

Wilner: I had to. (Reflecting.) To survive.

Me: Did Bell need to invent a telephone or was there a need for a hearing aid at that time in history?

Wilner: (With respectful frustration.) If you’re saying that “Necessity is the mother of all invention,” that would be a cliche. I’m not saying that. I’m saying the opposite. No one can control what they will learn. What we learn without intending or trying; what we didn’t mean to learn. That will be the topic of my essay.

Me: (speechless.)

The Farming of the Bones

That year, Edwidge Danticat’s novel, The Farming of the Bones, came right after James Joyce’s Dubliners in our AP Course. Wilner spoke seldom in class. Usually he would wait until the last moment of a conversation to add a confounding question. We had discussed the pathetic qualities of Maria, a character in James Joyce’s story, “Clay,” and we had reached a point of examining Maria’s sadness when Wilner entered the class’s conversation, “So, the story makes us sad that the old woman’s family betrayed her. I agree. But hasn’t she also betrayed her family and us, the readers, too? Maria made decisions. She chose to go to her relatives’ party. She chose the job where she worked, and she chose to sing the song that made everyone feel sorry for her. For me, she is courageous, not a victim. I don’t feel sorry for her. I believe that the author wants us to recognize how brave she is and how weak-minded people who feel sympathy for others can be. Maria is brave, not a victim who asks for pity. She knows that she’s deaf and misses things. It’s not a fact that her family or you are keeping from her.” Usually after Wilner’s question or comment, the room would go hush for a while.

On the day that we finished reading The Farming of the Bones, a group of students walked into the classroom complaining before class started.

David: Lavin, I’m so mad about this book. I stayed up late last night to finish it.

Me: Why are you mad?

Vicki: He’s mad because of what she did.

Me: What who did?

Ines: Amabelle, the woman in the book. The character. (Shaking the book as she spoke with frustration).

We began class before the bell rang that day. Students felt conflicted by their feelings for the character, Amabelle whose life story unifies the novel. She is a Haitian servant in the home of a wealthy Dominican soldier’s family. The story is set against the historical events surrounding the 1937 massacre of Haitians by the Dominican Dictator, Rafael Trujillo’s military. The sweeping majority of our class expressed anger with the book because the conclusion surprised them. The collective condemnation of the book went as far as Antonio saying, “Lavin, this whole book was a waste of time because of what happened last night, or what didn’t happen.” Then, Wilner spoke.

Wilner: (Addressing the entire class.) You know I’m just thinking that I never told anybody in class that I am from Haiti. Like so many of you, I lived in the Dominican Republic, too. So, I now the jokes about Haitians. You might notice I never laughed at them. Last night, you learned something about Amabelle, something that you did’t expect to learn. Sometimes, you will be thrilled by learning what you didn’t expect. Sometimes, you will be horrified. I was not surprised by how Amabelle’s story ended in last night’s reading. Amabelle is very beautiful. She a very rich life, regardless of her poverty, savoring her life. She loved the parents that she lost. She loved her lover, Sebastien. That was all very brave. She became the people from Haiti that she remembered after the massacre. Amabelle is all of those people for me.

Class: (Speechless)

In the classes after that discussion, it wasn’t unusual for Eva or Martin to say, when the discussion reached a lull, “Wil, tell us, what do you think?” One such day, I had asked students to write about a dream that recurs in their lives and how they make sense of it. Several students turned to Wilner, at one point and asked him to read his dream account aloud. Wilner had written about his dream in the third person. When he read from his dream journal, there was silence in the room:

. . . . . . . . . He always wakes up perspiring profusely and scared that he’s been thrown onto the ground, handcuffed and arrested. Dragged away to the police station. He always wakes up frightened that his grandmother is lost somewhere crying, moaning and distracted to the point of delirium and not able to understand where she is or what is happening to her. He feels the terror that comes with anger, trembling and confusion. He’s awake now. Is he hurt? Did he hurt the man? What year is it? Grandmother passed two years ago. OK. He’s in his room, not a prison. Sigh. Relief. Finally, a moment’s calm.

Kyle: Wil. Thank you. Thank you. (Silence.)

Kyle, then, began clapping and the whole class applauded, loud enough that the principal wondered what ever can be happening in there.

* All of the characters in this story are fictional fabrications with the exception of Edwidge Danticat whose novels and characters continually teach us lessons that we had not planned to learn.

0 notes

Text

“Puerto Rican Obituary” Revisited: The James Joyce Files (Part Four)

A Short Fiction

Pedro Pietri (1944-2004), depicted above in Photograph from Poetry Foundation.

Florentina Delgado rarely smiled.*

Doctors had just told her that Caridad, her infant daughter, might need to have an operation. Florentina was, even at the age of 18 years, serious and driven by complex questions. For each problem, she created a folder in a distinct color, labeled it, and filled it with pertinent documents and her notes. Tina’s notes made the Socratic Method seem idle-minded. She would position a prolific multitude of questions, her hand-written array of queries, in columns. She left many of the questions unanswered to move quickly to new questions. So that, when new questions occurred to her, she could add to the multi-variegated inquiry, she always carried the entire color-coded, rainbow of labeled folders in her book bag. There were that many problems when I met her. Tina and Cari, numerous folders neatly arranged, were facing a complicated spectrum of hard outcomes, and they were facing it all alone.

AN OFFICE IN THE HOSPITAL

Tina: So, you’re telling me that I have to make the decision. And, that, if the operation goes bad, it will be my fault, my bad decision. That’s what this document you want me to sign says?

Dr. Smith: Yes. It’s your responsibility.

Tina: Is that because you don’t want to take the blame if Caridad is disfigured or dies?

Dr. Smith: It’s just the law.

Tina: OK, Doctor. You have these medical students at all Cari’s appointments, and you told me that’s part of your other job, teaching medicine. And, there’s another paper here I need to sign to give X-Rays and info about Cari’s operation to the medical school for your teaching.

Dr. Smith: Yes.

Tina: I want Caridad to be paid for the info that comes from her case and pictures of her. And, I want you to sign a paper saying that the hospital will agree on a price, and I want you to sign a paper saying that you asked me, a high school student, with no training except the A.P. Biology course that I took last year, to decide if you do this complicated operation on Cari. And I want someone to translate at these meetings where you ask me to sign papers like this.

Dr. Smith: But your English is perfect.

Tina: I don’t understand all of the terms, and I heard a couple of your medical students speaking Spanish the last time you were examining Cari. Can you tell them to help instead of talking about stuff that has nothing to do with Cari?

Dr. Smith: I’m not sure.

Tina: About What?

Dr. Smith: Well . . .

Tina: If you’re not sure, how can I make these decisions on my own? When do I have to tell you if I’ll sign these permissions for the operation? And when can you sign the paper I’m giving you?

Against these odds, Tina’s voice was gentle. She spoke to the doctor with the same tranquility that her voice had when she spoke to Caridad or the principal of our school or to me. To “teach” Florentina, I had to study her method.

Compare James Joyce with another author.