#zuikaku/lexington

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

Chapters: 1/1 Fandom: 碧蓝航线 | Azur Lane (Video Game) Rating: General Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Relationships: Lexington/Zuikaku (Azur Lane), Implied Zuikaku/USS Enterprise (Azur Lane) Characters: Zuikaku (Azur Lane), Lexington (Azur Lane) Additional Tags: Fluff, Coffee Shops, First Dates, Accidental Relationship, Double Drabble Series: Part 12 of femslash feb 2024 Summary:

Zuikaku has had karma catch up with her. This will not stop her from trying to woo Lexington. Zuikaku is a disaster with dates. This doesn't stop Lexington from wooing her.

#fanfiction#azur lane#ijn zuikaku#uss lexington#zuikaku/lexington#minifemslashfeb2024#femslashfeb2024

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

USS Yorktown

She was the lead ship of the Yorktown-class aircraft carriers and was only the second US aircraft carrier built from the start as a carrier, the first being USS Ranger (CV-4). The Yorktown-class was a truly legendary class made up of 3 carriers, the Yorktown, Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8). These 3 sisters also had a cousin named USS Wasp (CV-7) that was built as a reduced size Yorktown to use up the remaining tonnage made available for the US under the Washington Naval treaty.

Back to the Yorktown, she was the first actual fleet carrier for the US Navy, being able to carry 90 aircraft. She was laid down in 1934, launched in 1936 and commissioned in 1937. Her early career was quite monotonous as she took part in fleet exercises and patrols in the Atlantic. She did come into contact with a couple of German U-boats but always left her escorting destroyers deal with the problem.

On the 7th of December 1941, during the attack on Pearl Harbor, she was still busy in the Atlantic ocean. On the 16th of that same month, she departed Norfolk for San Diego where she arrived on the 30th, she was loaded with new 20mm “Oerlikon” AA guns on top of her existing AA armament. This abundance of guns led dozens of sailors to go into the unofficial anti-aircraft gun business, according to a rapport "Yorktown bristled with more guns than a Mexican revolution movie." Soon after her arrival on the West coast she became the flagship of Rear Admiral Fletcher and formed Task Force 17 (TF-17).

Together with her sister, the Enterprise, she took part in the Marshalls-Gilberts raids, one of the first offensives of the Americans in the war. By the middle of February 1942 she had visited and again left Pearl Harbor for replenishment. This time she was headed for the Coral sea. She joined up with Task Force 11 (TF-11) that was led by the USS Lexington (CV-2). These 2 Task Forces were send there to stop the Japanese advancement on Papua New Guinea. On the 4th of May 1942 she launched her first attack on the Japanese that were attacking and advancing in Tulagi. This first attack consisted of 58 planes. The Yorktown launched another 3 attacks. In total the planes of the Yorktown sank the Japanese destroyer Kikuzuki, 3 minesweepers, 4 barges and 5 enemy seaplanes for a loss of 3 of her own planes (only one crew was never recovered). This was only the start of the battle however and the Japanese had 2 fleet carriers (Shokaku and Zuikaku) and a light carrier (Shoho) with all their escorts inbound.

On the 7th of May, the Yorktown, together with the Lexington, sank the Shoho. By the end of the day neither side had found the enemy carriers. This was until 3 Japanese planes mistook the Yorktown for one of their own carriers and attempted to land but were driven away with AA fire. Remarkable as it was, I would have wanted to see the faces on that ship when 20 minutes later another 3 planes made the exact same mistake. This time they did manage to shoot one down.

The next day the Lexington and Yorktown launched aircraft after a recon flight had found the enemy fleet, including the Shokaku and Zuikaku. The Yorktown hit the Shokaku 2 times with bombs which prevented her from launching any aircraft. Close to noon the US carriers were alerted of incoming enemy planes. The air patrol could down 17 enemy planes before they reached the Yorktown. The large 27 000 ton carrier managed to evade 8 torpedoes and all but one bomb. This bomb did penetrate multiple decks and exploded deep inside the ship, doing serious damage to her. Lexington however was hit far worse. Firefighting crews did get her keel almost back to an even level. Unfortunately an explosion within the ship caused a fire that reached an ammo room. The explosion that followed tore apart the Lexington. She was abandoned at 17:07 and sunk by a US destroyer later that day.

The battle of the Coral Sea should be noted for another reason. It was the first naval battle in history where surface ships never met each other. Only aircraft and their crews got to see the enemy fleet.

After the battle the Yorktown should have gone into the docks for at least 2 weeks to repair battle damage but there was little time for this. Admiral Nimitz knew the Japanese would attack Midway next and ordered Yorktown to sail with her 2 sisters together to Midway. This meant the Yorktown would be in dry dock for only 48 hours. However, every cloud has a silver lining. The Japanese were still in believe that they had sunk the Yorktown and the Lexington in the Coral sea and mistook the Yorktown for another carrier.

On the morning of the 4th of June 1942 PBY Catalina flying boats found the enemy fleet. The 3 sisters launched attack waves. Yorktown, that was in charge of the 3 Task Forces, launched 35 aircraft. Her dive bombers (SBD Dauntless) managed to score 3 1000 lbs bomb hits to the Soryu. These 3 hits sunk the Japanese carrier. Soryu’s sister ship, the Hiryu, launched 18 ‘Val’-bombers and 6 ‘zero’-fighters. They found the Yorktown quickly (but were still under the impression they were attacking another carrier). 3 Vals scored bomb hits, one bomb was still attached to it’s plane as it was shot down during it’s dive down to the carrier. Multiple fires were raging aboard the Yorktown. Even after taking such a beating she managed to survive thanks to her excellent crew and extensive training in damage control (something the Japanese lacked).

Her radar spotted incoming planes again and she sent out her fighters. 3 planes were shot down but this was not enough. 2 torpedoes hit the Yorktown’s side. Without power, 2 gaping holes in the hull, bomb craters and an increasing list to port the order was given to abandon the Yorktown.

She did get her revenge on the Hiryu. Part of her planes were diverted to the Enterprise after the first bomb attack and these planes were now attacking the Hiryu. She took 4 direct hits and sunk.

The old lady did not want to give in however. She stayed afloat throughout the night and on the 6th of June a salvage party went aboard.

Underneath the water a Japanese submarine had found the Task Force and launched 4 torpedoes. 2 hit the Yorktown at her starboard side, letting in even more water. Unbelievably she stayed afloat for another night. At last then, on the morning of the 7th of June, her list increased rapidly and she rolled upside-down. The USS Yorktown had finally been sunk.

She received 3 battle stars for her contribution and would have a name successor in the form of the Essex-class USS Yorktown CV-10.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

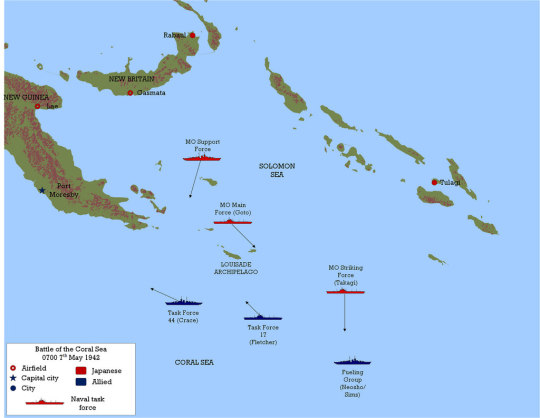

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the battle is historically significant as the first action in which aircraft carriers engaged each other and the first in which the opposing ships neither sighted nor fired directly upon one another.

In an attempt to strengthen their defensive position in the South Pacific, the Japanese decided to invade and occupy Port Moresby (in New Guinea) and Tulagi (in the southeastern Solomon Islands). The plan, Operation Mo, involved several major units of Japan's Combined Fleet. They included two fleet carriers and a light carrier to provide air cover for the invasion forces, under the overall command of Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue.

The U.S. learned of the Japanese plan through signals intelligence and sent two U.S. Navy carrier task forces and a joint Australian-American cruiser force to oppose the offensive, under the overall command of U.S. Admiral Frank J. Fletcher.

On 3–4 May, Japanese forces successfully invaded and occupied Tulagi, although several of their supporting warships were sunk or damaged in surprise attacks by aircraft from the U.S. fleet carrier Yorktown. Now aware of the presence of enemy carriers in the area, the Japanese fleet carriers advanced towards the Coral Sea with the intention of locating and destroying the Allied naval forces. On the evening of 6 May, the two carrier forces came within 70 nmi (81 mi; 130 km) of each other, unbeknownst to anyone. On 7 May, both sides launched airstrikes. Each mistakenly believed they were attacking their opponent's fleet carriers, but were actually attacking other units, with the U.S. sinking the Japanese light carrier Shōhō and the Japanese sinking a U.S. destroyer and heavily damaging a fleet oiler, which was later scuttled. The next day, each side found and attacked the other's fleet carriers, with the Japanese fleet carrier Shōkaku damaged, the U.S. fleet carrier Lexington critically damaged and later scuttled, and the fleet carrier Yorktown damaged. With both sides having suffered heavy losses in aircraft and carriers damaged or sunk, the two forces disengaged and retired from the area. Because of the loss of carrier air cover, Inoue recalled the Port Moresby invasion fleet with the intention of trying again later.

Although a victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk, the battle would prove to be a strategic victory for the Allies in several ways. The battle marked the first time since the start of the war that a major Japanese advance had been checked by the Allies. More importantly, the Japanese fleet carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku, the former damaged and the latter with a depleted aircraft complement, were unable to participate in the Battle of Midway the following month, but Yorktown participated on the Allied side, which made for rough parity in aircraft between the adversaries and contributed significantly to the U.S. victory. The severe losses in carriers at Midway prevented the Japanese from reattempting to invade Port Moresby by sea and helped prompt their ill-fated land offensive over the Kokoda Track. Two months later, the Allies took advantage of Japan's resulting strategic vulnerability in the South Pacific and launched the Guadalcanal Campaign. That and the New Guinea Campaign eventually broke Japanese defenses in the South Pacific and were significant contributors to Japan's ultimate surrender, marking the end of World War II.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Coral_Sea

0 notes

Text

20 Most Powerful Submarines, Aircraft Carriers, Bombers and Fighter Jets EVER

The real best of the best.In today's world, where every day it seems a new piece of military technology is poised to take over the battlefield and make everything else obsolete, there are several weapons of war that seem to have some staying power. Aircraft carriers, while some may consider them obsolete, remain one of the ultimate ways to display national power and prestige, with the unique capability to attack targets from the world's seas with deadly accuracy.Submarines have many uses. Whether it is to exercise sea control, deter an enemy with underwater nuclear weapons or ensure you have the ability to strike with various types of conventional weapons like cruise missiles on land, subs seem to be only gaining in prominence. (This first appeared several years ago.)Then there is the bomber. Some are old, like the B-52. Some are just getting started, like the B-21 Raider. Some we don't know much about, like Russia's PAK-FA. Yet, one thing is clear: Bombers can still make or break any conflict that could occur now or in the future. And fighter jets are not going anywhere. The F-35 is the ultimate example--considering the massive cost--of this important military asset having clear staying power (the only debate at this point is whether it will be manned or unmanned). So what are the best carriers, submarines, bombers and fighters ever? Robert Farley, one of the world's best defense experts and frequent TNI contributor, has written on this subject extensively. For your reading pleasure, we have packed together several pieces that take this subject on into this one post, which were written several years ago. Let the debate begin. ***The first true aircraft carriers entered service at the end of World War I, as the Royal Navy converted several of its excess warships into large, floating airfields. During the interwar period, Japan and the United States would make their own conversions, and all three navies would supplement these ships with purpose-built carriers. Within months of the beginning of hostilities in September 1939, the carrier demonstrated its worth in a variety of maritime tasks.By the end of 1941, carriers would become the world’s dominant capital ship. These are the five most lethal carriers to serve in the world’s navies, selected on the basis of their contribution to critical operations, and on their longevity and resilience.USS Enterprise:The U.S. Navy supplemented Lexington and Saratoga, the most effective of the interwar battlecruiser conversions, with the purpose-built USS Ranger. Experience with all three ships demonstrated that the next purpose-built class would require a larger hull and flight deck, as well as a heavier anti-aircraft armament. This resulted in USS Yorktown and USS Enterprise, which along with their third sister (USS Hornet) would play a critical role in stopping the Imperial Japanese Navy’s advance in 1942. Capable of cruising at 33 knots, Enterprise displaced around 24,000 tons and could carry up to 90 aircraft.While both Hornet and Yorktown were lost in the carrier battles of 1942, Enterprise served throughout the entire war. She helped search for the Japanese fleet in the wake of Pearl Harbor, and carried out the first reprisal raids in the early months of the war. She escorted Hornet on the Doolittle Raid, then helped sink four Japanese flattops at the Battle of Midway. She filled a crucial role during the Battles of Guadalcanal, surviving several near-catastrophic Japanese attacks.Later in the war, Enterprise operated with the growing American carrier fleet as it formed core of the counter-offensive that would roll up Japanese possessions in the Pacific. Enterprise fought at Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf, helping to destroy the heart of Japanese naval aviation. She served in the final raids against Japan in 1945 until a kamikaze caused critical damage in May. Returning to service just as the war ended, she helped return American soldiers to the United States in Operation Magic Carpet. Enterprise was the most decorated ship in any navy during World War II, but sadly post-war preservation efforts failed, and the carrier was scrapped in 1960.HMS Illustrious:Between September 1939 and April 1942, the Royal Navy lost five of its seven pre-war aircraft carriers. HMS Illustrious and her three sisters filled the gap. Laid down in 1937, Illustrious traded aircraft complement for an armored deck, an innovation that would make the ship more robust than her Japanese or American counterparts. Displacing 23,000 tons, Illustrious could make 30 knots and carrying 36 aircraft.Illustrious’ first major achievement came in November 1940, when her Swordfish torpedo bombers attacked the battleships of the Italian navy at anchor at Taranto. The attack, carried out on a shoestring compared to the great raids of the Pacific War, nevertheless managed to sink or heavily damage three Italian battleships. Illustrious spent the next few months carrying out raids in the Mediterranean and covering the evacuation of Greece. In the course of the latter, she survived several hits from German divebombers.After receiving repairs in the United States, Illustrious operated against the Japanese in the Indian Ocean. She returned to the European theater in 1943, making additional raids on Norway and in support of Allied landings in Italy. Later Illustrious returned to the Pacific, where supplied with superior American carrier aircraft, she helped spearhead the Royal Navy counter-offensive into Southeast Asia. After surviving a kamikaze attack, she returned to Great Britain and eventually served as a training carrier before being scrapped in 1957.HIJMS Zuikaku:Zuikaku represented the zenith of pre-war Japanese carrier development. Along with her sister Shokaku, Zuikaku filled out Kido Butai with the addition of two large, fast, modern carriers. Displacing 32,000 tons and capable of carrying 72 aircraft, Zuikaku could make 34 knots, and absorb a relatively large amount of battle damage.The size and modernity of the carriers meant that they could handle a greater operational tempo early in the war. After the Pearl Harbor raid, they participated in the Indian Ocean Raid, helping to sink the British carrier Hermes and several other ships. Afterward, Zuikaku and her sister deployed to Port Moresby to cover Japanese landings in what became the Battle of Coral Sea. Zuikaku survived undamaged, and contributed to the sinking of USS Lexington, but because of a lack of aircraft could not participate in the Battle of Midway.Zuikaku continued to form the core of the Japanese carrier fleet into 1944, participating in and surviving the battles of Guadalcanal (where her aircraft helped sink USS Hornet) and the Battle of Philippine Sea. By October 1944, her supply of aircraft and pilots was almost completely exhausted. At the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Zuikaku and several other carriers served as bait for Halsey’s battleships and carriers, luring them away from the center of the Japanese attack. The last survivor of the Pearl Harbor attack, Zuikaku sank under a barrage of bombs and torpedoes.USS Midway:USS Midway entered service in September 1945, shortly after the end of hostilities against Japan. She displaced 45,000 tons, could make 33 knots, and could carry roughly 100 aircraft. Midway and her sisters represented a step beyond the Essex-class carriers that had won the Pacific War, and promised to introduce a new era of naval aviation.Upon commissioning, Midway became the world’s most lethal aircraft carrier. The offensive power of her air group exceeded that of the Essex carriers then in service, and with the introduction of jet aircraft the gap would grow. With the A-2 Savage carrier-based bomber, Midway and her sisters briefly became the only carriers in the world capable of delivering nuclear weapons.Midway underwent extensive modification over the course of her career, eventually acquiring an angled flight deck and other innovations. Although she missed Korea, Midway operated off Vietnam, and continued to serve as the larger “supercarriers” came online. She found heavy use in the Gulf War of 1990, as her (relative) small size gave her an advantage in maneuverability over the more modern supercarriers. Midway left service in 1992, having spanned the history of naval aviation from the F6F Hellcat to the F/A-18 Hornet.USS Theodore Roosevelt:The ten Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carriers have been the world’s dominant capital ships since they began to enter service in the late 1970s. Constructed over a period spanning nearly 35 years, the class continues to provide the core of American naval power. Among the most active of the Nimitz class has been the USS Theodore Roosevelt, first of the second group of ships. Roosevelt entered service in 1986; she displaces over 100,000 tons, carries between 75-80 aircraft, and can make 30 knots top speed.Roosevelt has served in most of the conflicts of the post Cold-War era. In 1991 she launched strikes against Iraqi targets during Operation Desert Storm. In 1999, her aircraft conducted strikes in Kosovo and Serbia in service of Operation Allied Force. After the September 11 attacks, Roosevelt deployed to the Middle East and participated in the first sorties against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Operation Enduring Freedom. Two years later, her aircraft flew against Iraqi targets again in the first days of Operation Iraqi Freedom. After a refit, Roosevelt launched strikes against both Afghan and Iraqi targets in the latter part of the decade. Most recently, Roosevelt helped blockade Yemeni ports against a suspected Iranian arms convoy.Like her sister ships, Roosevelt has already undergone substantial modification across the course of her thirty year career, and the Navy expects that these refits will continue into the future. Current projections suggest that she will leave service around 2035, which would give the carrier a nearly fifty-year span of lethality.Wrap:Pundits and analysts have predicted the obsolescence and demise of the aircraft carrier since the waning days of World War II. At the moment, however, the Russian, Indian, British, Chinese, French, and American navies continue to put faith, and resources, into carrier aviation. Despite the vulnerability of the big ships to attack, they provide a unique combination of presence, prestige, and lethality that continues to make them attractive to the world’s most powerful navies.***There have been three great submarine campaigns in history, and one prolonged duel. The First and Second Battles of the Atlantic pitted German U-boats against the escorts and aircraft of the United Kingdom and the United States. The Germans very nearly won World War I with the first campaign, and badly drained Allied resources in the second. In the third great campaign, the submarines of the US Navy destroyed virtually the entire commercial fleet of Japan, bringing the Japanese economy to its knees. US subs also devastated the Imperial Japanese Navy, sinking several of Tokyo’s most important capital ships.But the period most evocative of our modern sense of submarine warfare was surely the forty year duel between the submarines of the USSR and the boats of the various NATO navies. Over the course of the Cold War, the strategic nature of the submarine changed; it moved from being a cheap, effective killer of capital ships to a capital ship in its own right. This was especially the case with the boomers, submarines that carried enough nuclear weapons to kill millions in a few minutes.As with previous “5 Greatest” lists, the answers depend on the parameters; different sets of metrics will generate different lists. Our metrics concentrate on the strategic utility of specific submarine classes, rather than solely on their technical capabilities.· Was the submarine a cost-effective solution to a national strategic problem?· Did the submarine compare favorably with its contemporaries?· Was the submarine’s design innovative?And with that, the five best submarines of all time:U-31:The eleven boats of the U-31 class were constructed between 1912 and 1915. They operated in both of the periods of heavy action for German U-boats, early in the war before the suspension of unrestricted warfare, and again in 1917 when Germany decided to go for broke and cut the British Empire off at the knees. Four of these eleven boats (U-35, U-39, U-38, and U-34) were the four top killers of World War I; indeed, they were four of the five top submarines of all time in terms of tonnage sunk (the Type VII boat U-48 sneaks in at number 3). U-35, the top killer, sank 224 ships amounting to over half a million tons.The U-31 boats were evolutionary, rather than revolutionary; they represented the latest in German submarine technology for the time, but did not differ dramatically from their immediate predecessors or successors. These boats had good range, a deck gun for destroying small shipping, and faster speeds surfaced than submerged. These characteristics allowed the U-31 class and their peers to wreak havoc while avoiding faster, more powerful surface units. They did offer a secure, stealthy platform for carrying out a campaign that nearly forced Great Britain from the war. Only the entry of the United States, combined with the development of innovative convoy tactics by the Royal Navy, would stifle the submarine offensive. Three of the eleven boats survived the war, and were eventually surrendered to the Allies.Balao:The potential for a submarine campaign against the Japanese Empire was clear from early in the war. Japanese industry depended for survival on access to the natural resources of Southeast Asia. Separating Japan from those resources could win the war. However, the pre-war USN submarine arm was relatively small, and operated with poor doctrine and bad torpedoes. Boats built during the war, including primarily the Gato and Balao class, would eventually destroy virtually the entire Japanese merchant marine.The Balao class represented very nearly the zenith of the pre-streamline submarine type. War in the Pacific demanded longer ranges and more habitability than the relatively snug Atlantic. Like their predecessors the Gato, the Balaos were less maneuverable than the German Type VII subs, but they made up for this in strength of hull and quality of construction. Compared with the Type VII, the Balaos had longer range, a larger gun, more torpedo tubes, and a higher speed. Of course, the Balaos operated in a much different environment, and against an opponent less skilled in anti-submarine warfare. The greatest victory of a Balao was the sinking of the 58000 ton HIJMS Shinano by Archerfish.Eleven of 120 boats were lost, two in post-war accidents. After the war Balao class subs were transferred to several friendly navies, and continued to serve for decades. One, the former USS Tusk, remains in partial commission in Taiwan as Hai Pao.Type XXIIn some ways akin to the Me 262, the Type XXI was a potentially war-winning weapon that arrived too late to have serious effect. The Type XXI was the first mass produced, ocean-going streamlined or “true” submarine, capable of better performance submerged than on the surface. It gave up its deck gun in return for speed and stealth, and set the terms of design for generations of submarines.Allied anti-submarine efforts focused on identifying boats on the surface (usually in transit to their patrol areas) then vectoring killers (including ships and aircraft) to those areas. In 1944 the Allies began developing techniques for fighting “schnorkel” U-boats that did not need to surface, but remained unprepared for combat against a submarine that could move at 20 knots submerged.In effect, the Type XXI had the stealth to avoid detection prior to an attack, and the speed to escape afterward. Germany completed 118 of these boats, but because of a variety of industrial problems could only put four into service, none of which sank an enemy ship. All of the Allies seized surviving examples of the Type XXI, using them both as models for their own designs and in order to develop more advanced anti-submarine technologies and techniques. For example, the Type XXI was the model for the Soviet “Whiskey” class, and eventually for a large flotilla of Chinese submarines.George Washington:We take for granted the most common form of today’s nuclear deterrent; a nuclear submarine, bristling with missiles, capable of destroying a dozen cities a continent away. These submarines provide the most secure leg of the deterrent triad, as no foe could reasonably expect to destroy the entire submarine fleet before the missiles fly.The secure submarine deterrent began in 1960, with the USS George Washington. An enlarged version of the Skipjack class nuclear attack sub, George Washington’s design incorporated space for sixteen Polaris ballistic missiles. When the Polaris became operational, USS George Washington had the capability from striking targets up to 1000 miles distant with 600 KT warheads. The boats would eventually upgrade to the Polaris A3, with three warheads and a 2500 mile range. Slow relative to attack subs but extremely quiet, the George Washington class pioneered the “go away and hide” form of nuclear deterrence that is still practiced by five of the world’s nine nuclear powers.And until 1967, the George Washington and her sisters were the only modern boomers. Their clunky Soviet counterparts carried only three missiles each, and usually had to surface in order to fire. This made them of limited deterrent value. But soon, virtually every nuclear power copied the George Washington class. The first “Yankee” class SSBN entered service in 1967, the first Resolution boat in 1968, and the first of the French Redoutables in 1971. China would eventually follow suit, although the PLAN’s first genuinely modern SSBNs have only entered service recently. The Indian Navy’s INS Arihant will likely enter service in the next year or so.The five boats of the George Washington class conducted deterrent patrols until 1982, when the SALT II Treaty forced their retirement. Three of the five (including George Washington) continued in service as nuclear attack submarines for several more years.Los Angeles:Immortalized in the Tom Clancy novels Hunt for Red October and Red Storm Rising, the U.S. Los Angeles class is the longest production line of nuclear submarines in history, constituting sixty-two boats and first entering service in 1976. Forty-one subs remain in commission today, continuing to form the backbone of the USN’s submarine fleet.The Los Angeles (or 688) class are outstanding examples of Cold War submarines, equally capable of conducting anti-surface or anti-submarine warfare. In wartime, they would have been used to penetrate Soviet base areas, where Russian boomers were protected by rings of subs, surface ships, and aircraft, and to protect American carrier battle groups.In 1991, two Los Angeles class attack boats launched the first ever salvo of cruise missiles against land targets, ushering in an entirely new vision of how submarines could impact warfare. While cruise missile armed submarines had long been part of the Cold War duel between the United States and the Soviet Union, most attention focused either on nuclear delivery or anti-ship attacks. Submarine launched Tomahawks gave the United States a new means for kicking in the doors of anti-access/area denial systems. The concept has proven so successful that four Ohio class boomers were refitted as cruise missile submarines, with the USS Florida delivering the initial strikes of the Libya intervention.The last Los Angeles class submarine is expected to leave service in at some point in the 2020s, although outside factors may delay that date. By that time, new designs will undoubtedly have exceeded the 688 in terms of striking land targets, and in capacity for conducting anti-submarine warfare. Nevertheless, the Los Angeles class will have carved out a space as the sub-surface mainstay of the world’s most powerful Navy for five decades.Conclusion:Fortunately, the United States and the Soviet Union avoided direct conflict during the Cold War, meaning that many of the technologies and practices of advanced submarine warfare were never employed in anger. However, every country in the world that pretends to serious maritime power is building or acquiring advanced submarines. The next submarine war will look very different from the last, and it’s difficult to predict how it will play out. We can be certain, however, that the fight will be conducted in silence.Honorable Mention: Ohio, 260O-21, Akula, Alfa, Seawolf, Swiftsure, I-201, Kilo, S class, Type VII***Bombers are the essence of strategic airpower. While fighters have often been important to air forces, it was the promise of the heavy bomber than won and kept independence for the United States Air Force and the Royal Air Force. At different points in time, air forces in the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Italy have treated bomber design and construction as a virtually all-consuming obsession, setting fighter and attack aviation aside.However, even the best bombers are effective over only limited timespans. The unlucky state-of-the-art bombers of the early 1930s met disaster when put into service against the pursuit aircraft of the late 1930s. The B-29s that ruled the skies over Japan in 1945 were cut to pieces above North Korea in 1950. The B-36 Peacemaker, obsolete before it was even built, left service in a decade. Most of the early Cold War bombers were expensive failures, eventually to be superseded by ICBMs and submarine-launched ballistic missiles.States procure bombers, like all weapons, to serve strategic purposes. This list employs the following metrics of evaluation:· Did the bomber serve the strategic purpose envisioned by its developers?· Was the bomber a sufficiently flexible platform to perform other missions, and to persist in service?· How did the bomber compare with its contemporaries in terms of price, capability, and effectiveness?And with that, the five best bombers of all time:Handley Page Type O 400:The first strategic bombing raids of World War I were carried out by German zeppelins, enormous lighter than aircraft that could travel at higher altitudes than the interceptors of the day, and deliver payloads against London and other targets. Over time, the capabilities of interceptors and anti-aircraft artillery grew, driving the Zeppelins to other missions. Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and others began working on bombers capable of delivering heavy loads over long distance, a trail blazed (oddly enough) by the Russian Sikorsky Ilya Muromets.Even the modest capabilities of the early bombers excited the airpower theorists of the day, who imagined the idea of fleets of bombers striking enemy cities and enemy industry. The Italians developed the Caproni family of bombers, which operated in the service of most Allied countries at one time or another. German Gotha bombers would eventually terrorize London again, catalyzing the Smuts Report and the creation of the world’s first air force.Faster and capable of carrying more bombs than either the Gotha IVs or the Caproni Ca.3, the Type O 400 had a wingspan nearly as large as the Avro Lancaster. With a maximum speed of 97 miles per hour with a payload of up to 2000 lbs, O 400s were the mainstay of Hugh Trenchard’s Independent Air Force near the end of the war, a unit which struck German airfields and logistics concentration well behind German lines. These raids helped lay the foundation of interwar airpower theory, which (at least in the US and the UK) envisioned self-protecting bombers striking enemy targets en masse.Roughly 600 Type O bombers were produced during World War I, with the last retiring in 1922. Small numbers served in the Chinese, Australian, and American armed forces.Junkers Ju 88:The Junkers Ju-88 was one of the most versatile aircraft of World War II. Although it spent most of its career as a medium bomber, it moonlighted as a close attack aircraft, a naval attack aircraft, a reconnaissance plane, and a night fighter. Effective and relatively cheap, the Luftwaffe used the Ju 88 to good effect in most theaters of war, but especially on the Eastern Front and in the Mediterranean.Designed with dive bomber capability, the Ju 88 served in relatively small numbers in the invasion of Poland, the invasion of Norway, and the Battle of France. The Ju-88 was not well suited to the strategic bombing role into which it was forced during the Battle of Britain, especially in its early variants. It lacked the armament to sufficiently defend itself, and the payload to cause much destruction to British industry and infrastructure. The measure of an excellent bomber, however, goes well beyond its effectiveness at any particular mission. Ju 88s were devastating in Operation Barbarossa, tearing apart Soviet tank formations and destroying much of the Soviet Air Forces on the ground. Later variants were built as or converted into night fighters, attacking Royal Air Force bomber formations on the way to their targets.In spite of heavy Allied bombing of the German aviation industry, Germany built over 15,000 Ju 88s between 1939 and 1945. They operated in several Axis air forces.De Havilland Mosquito:The de Havilland Mosquito was a remarkable little aircraft, capable of a wide variety of different missions. Not unlike the Ju 88, the Mosquito operated in bomber, fighter, night fighter, attack, and reconnaissance roles. The RAF was better positioned than the Luftwaffe to utilized the specific qualities of the Mosquito, and avoid forcing it into missions in could not perform.Relatively lightly armed and constructed entirely of wood, the Mosquito was quite unlike the rest of the RAF bomber fleet. Barely escaping design committee, the Mosquito was regarded as easy to fly, and featured a pressurized cockpit with a high service ceiling. Most of all, however, the Mosquito was fast. With advanced Merlin engines, a Mosquito could outpace the German Bf109 and most other Axis fighters.Although the bomb load of the Mosquito was limited, its great speed, combined with sophisticated instrumentation, allowed it to deliver ordnance with more precision than most other bombers. During the war, the RAF used Mosquitoes for various precision attacks against high value targets, including German government installations and V weapon launching sites. As pathfinders, Mosquitoes flew point on bomber formations, leading night time bombing raids that might otherwise have missed their targets. Mosquitos also served in a diversionary role, distracting German night fighters from the streams of Halifaxes and Lancasters striking urban areas.De Havilland produced over 7000 Mosquitoes for the RAF and other allied air forces. Examples persisted in post-war service with countries as varied as Israel, the Republic of China, Yugoslavia, and the Dominican RepublicAvro Lancaster:The workhorse of the RAF in World War II, the Lancaster carried out the greater part of the British portion of the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO). Led by Arthur Harris, Bomber Command believed that area bombing raids, targeted against German civilians, conducted at night, would destroy German morale and economic capacity and bring the war to a close. Accordingly, the Lancaster was less heavily armed than its American contemporaries, as it depended less on self-defense in order to carry out its mission.The first Lancasters entered service in 1942. The Lancaster could carry a much heavier bomb load than the B-17 or the B-24, while operating at similar speeds and at a slightly longer range. The Lancaster also enjoyed a payload advantage over the Handley Page Halifax. From 1942 until 1945, the Lancaster would anchor the British half of the CBO, eventually resulting in the destruction of most of urban Germany and the death of several hundred thousand German civilians.There are reasons to be skeptical of the inclusion of the Lancaster. The Combined Bomber Offensive was a strategic dead-end, serving up expensive four-engine bombers as a feast for smaller, cheaper German fighters. Battles were fought under conditions deeply advantageous to the Germans, as damaged German planes could land, and shot down German pilots rescued and returned to service. Overall, the enormous Western investment in strategic bombing was probably one of the greatest grand strategic miscalculations of the Second World War. Nevertheless, this list needs a bomber from the most identifiable bomber offensive in history, and the Lancaster was the best of the bunch.Over 7000 Lancasters were built, with the last retiring in the early 1960s after Canadian service as recon and maritime patrol aircraft.Boeing B-52 Stratofortress:The disastrous experience of B-29 Superfortresses over North Korea in 1950 demonstrated that the United States would require a new strategic bomber, and soon. Unfortunately, the first two generations of bombers chosen by the USAF were almost uniformly duds; the hopeless B-36, the short-legged B-47, the dangerous-to-its-own-pilots B-58, and the obsolete-before-it-flew XB-70. The vast bulk of these bombers quickly went from wastes of taxpayer money to wastes of space at the Boneyard. None of the over 2500 early Cold War bombers ever dropped a bomb in anger.The exception was the B-52.The BUFF was originally intended for high altitude penetration bombing into the Soviet Union. It replaced the B-36 and the B-47, the former too slow and vulnerable to continue in the nuclear strike mission, and the latter too short-legged to reach the USSR from U.S. bases. Slated for replacement by the B-58 and the B-70, the B-52 survived because it was versatile enough to shift to low altitude penetration after the increasing sophistication of Soviet SAMs made the high altitude mission suicidal.And this versatility has been the real story of the B-52. The BUFF was first committed to conventional strike missions in service of Operation Arc Light during the Vietnam War. In Operation Linebacker II, the vulnerability of the B-52 to air defenses was made manifest when nine Stratofortresses were lost in the first days of the campaign. But the B-52 persisted. In the Gulf War, B-52s carried out saturation bombing campaigns against the forward positions of the Iraqi Army, softening and demoralizing the Iraqis for the eventual ground campaign. In the War on Terror, the B-52 has acted in a close air support role, delivering precision-guided ordnance against small concentrations of Iraqi and Taliban insurgents.Most recently, the B-52 showed its diplomatic chops when two BUFFs were dispatched to violate China’s newly declared Air Defense Zone. The BUFF was perfect for this mission; the Chinese could not pretend not to notice two enormous bombers travelling at slow speed through the ADIZ.742 B-52s were delivered between 1954 and 1963. Seventy-eight remain in service, having undergone multiple upgrades over the decades that promise to extend their lives into the 2030s, or potentially beyond. In a family of short-lived airframes, the B-52 has demonstrated remarkable endurance and longevity.Conclusion:Over the last century, nations have invested tremendous resources in bomber aircraft. More often than not, this investment has failed to bear strategic fruit. The very best aircraft have been those that could not only conduct their primary mission effectively, but that were also sufficiently flexible to perform other tasks that might be asked of them. Current air forces have, with some exceptions, effectively done away with the distinctions between fighters and bombers, instead relying on multi-role fighter-bombers for both missions. The last big, manned bomber may be the American LRS-B, assuming that project ever gets off the ground.Honorable Mention:Grumman A-6 Intruder, MQ-1 Predator, Caproni Ca.3, Tupolev Tu-95 “Bear,” Avro Vulcan, Tupolev Tu-22M “Backfire.”***What are the five greatest fighter aircraft of all time? Like the same question asked of tanks, cars, or rock and roll guitarists, the answer invariably depends on parameters. For example, there are few sets of consistent parameters that would include both the T-34 and the King Tiger among the greatest of all tanks. I know which one I’d like to be driving in a fight, but I also appreciate that this isn’t the most appropriate way to approach the question. Similarly, while I’d love to drive a Porsche 959 to work every morning, I’d be hesitant to list it ahead of the Toyota Corolla on a “best of” compilation.Nations buy fighter aircraft to resolve national strategic problems, and the aircraft should accordingly be evaluated on their ability to solve or ameliorate these problems. Thus, the motivating question is this: how well did this aircraft help solve the strategic problems of the nations that built or bought it? This question leads to the following points of evaluation:Fighting characteristics: How did this plane stack up against the competition, including not just other fighters but also bombers and ground installations?Reliability: Could people count on this aircraft to fight when it needed to, or did it spend more time under repair than in the air?Cost: What did the organization and the nation have to pay in terms of blood and treasure to make this aircraft fly?These are the parameters; here are my answers:Spad S.XIIIIn the early era of military aviation, technological innovation moved at such speed that state of the art aircraft became obsolete deathtraps within a year. Engineers in France, Britain, Germany and Italy worked constantly to outpace their competitors, producing new aircraft every year to throw into the fight. The development of operational tactics trailed technology, although the input of the best flyers played an important role in how designers put new aircraft together.In this context, picking a dominant fighter from the era is difficult. Nevertheless, the Spad S.XIII stands out in terms of its fighting characteristics and ease of production. Based in significant part on the advice of French aviators such as Georges Guynemer, the XIII lacked the maneuverability of some of its contemporaries, but could outpace most of them and performed very well in either a climb or a dive. It was simple enough to produce that nearly 8,500 such aircraft eventually entered service. Significant early reliability problems were worked out by the end of the war, and in any case were overwhelmed by the XIII’s fighting ability.The S.XIII filled out not only French fighter squadrons, but also the air services of Allied countries. American ace Eddie Rickenbacker scored twenty of his kills flying an XIII, many over the most advanced German fighters of the day, including the Fokker D.VII.The Spad XIII helped the Allies hold the line during the Ludendorff Offensive, and controlled the skies above France during the counter-offensive. After the war, it remained in service in France, the United States, and a dozen other countries for several years. In an important sense, the Spad XIII set the post-war standard for what a pursuit aircraft needed to do.Grumman F6F HellcatOf course, it is not only air forces that fly fighter aircraft. The F6F Hellcat can’t compare with the Spitfire, the P-51, or the Bf 109 on many basic flight characteristics, although its ability to climb was first-rate. What the F6F could do, however, was reliably fly from aircraft carriers, and it rode point on the great, decisive U.S. Navy carrier offensive of World War II. Entering the war in September 1943, it won 75% of USN aerial victories in the Pacific. USN ace David McCampbell shot down nine Japanese aircraft in one day flying a Hellcat .The F6F was heavily armed, and could take considerably more battle damage than its contemporaries. Overall, the F6F claimed nearly 5,200 kills at a loss of 270 aircraft in aerial combat, including a 13:1 ratio against the Mitsubishi A6M Zero.The USN carrier offensive of the latter part of World War II is probably the greatest single example of the use of decisive airpower in world history. Hellcats and their kin (the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bomber and the Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber) destroyed the fighting power of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), cracked open Japan’s island empire, and exposed the Japanese homeland to devastating air attack and the threat of invasion.In 1943, the United States needed a fighter robust enough to endure a campaign fought distant from most bases, yet fast and agile enough to defeat the best that the IJN could offer. Tough and reliable as a brick, the Hellcat fit that role. Put simply, the Honda Accord is, in its own way, a great car; the Honda Accords of the fighter world also deserve their day.Messerschmitt Me-262 SwallowThe Me 262 Schwalbe (Swallow, in English) failed to win the war for Germany, and couldn’t stop the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO). Had German military authorities made the right decisions, however, it might at least have accomplished the second.Known as the world’s first operational jet fighter, full-scale production of the Me 262 was delayed by resistance within the German government and the Luftwaffe to devoting resources to an experimental aircraft without a clear role. Early efforts to turn it into a fighter-bomber fell flat. As the need for a superlative interceptor become apparent, however, the Me 262 found its place. The Swallow proved devastating against American bomber formations, and could outrun American pursuit aircraft.The Me 262 was hardly a perfect fighter: it lacked the maneuverability of the best American interceptors, and both American and British pilots developed tactics for managing the Swallow. Although production suffered from some early problems with engines, by the later stages of the conflict, manufacturing was sufficiently easy that the plane could be mass-produced in dispersed, underground facilities.But had it come on line a bit earlier, the Me 262 might have torn the heart out of the CBO. The CBO in 1943 was a touch and go affair; dramatically higher bomber losses in 1943 could well have led Churchill and Roosevelt to scale back the production of four engine bombers in favor of additional tactical aircraft. Without the advantage of long-range escorts, American bombers would have proven easy prey for the German jet. Moreover, the Me 262 would have been far more effective without the constant worry of P-47s and P-51s strafing its airfields and tracking its landings.Nazi Germany needed a game changer, a plane capable of making the price too high for the Allies to keep up the CBO. The Me 262 came onto the scene too late to solve that problem, but it’s hard to imagine any aircraft that could have come closer. Ironically, this might have accelerated Allied victory, as the Combined Bomber Offensive resulted in not only the destruction of urban Germany, but in the waste of substantial Allied resources. Win-win.Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 “Fishbed”An odd choice for this list? The MiG-21 is known largely as fodder for the other great fighters of the Cold War, and for having an abysmal kill ratio. The Fishbed (in NATO terminology) has served as a convenient victim in Vietnam and in a variety of Middle Eastern wars, some of which it fought on both sides.But… the MiG-21 is cheap, fast, maneuverable, has low maintenance requirements. It’s relatively easy to learn to fly, although not necessarily easy to learn how to fly well. Air forces continued to buy the MiG-21 for a long time. Counting the Chengdu J-7 variant, perhaps 13,000 MiG-21s have entered service around the world. In some sense, the Fishbed is the AK-47 (or the T-34, if you prefer) of the fighter world. Fifty countries have flown the MiG-21, and it has flown for fifty-five years. It continues to fly as a key part of twenty-six different air forces, including the Indian Air Force, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force, the Vietnamese People’s Air Force, and the Romanian Air Force. Would anyone be surprised if the Fishbed and its variants are still flying in 2034?The MiG-21 won plaudits from American aggressor pilots at Red Flag, who celebrated its speed and maneuverability, and played (through the contribution of North Vietnamese aces such as Nguyễn Văn Cốc ) an important role in redefining the requirements of air superiority in the United States. When flown well, it remains a dangerous foe.Most of life is about just showing up, and since 1960 no fighter has shown up as consistently, and in as many places, as has the MiG-21. For countries needing a cheap option for claiming control of their national airspace, the MiG-21 has long solved problems, and will likely continue to serve in this role.McDonnell Douglas F-15 EagleWhat to say about the F-15 Eagle? When it came into service in 1976, it was immediately recognized as the best fighter in the world. Today, it is arguably still the best all-around, cost-adjusted fighter, even if the Su-27 and F-22 have surpassed it in some ways. If one fighter in American history could take the name of the national symbol of the United States, how could it be anything other than the F-15?The Eagle symbolizes the era of American hegemony, from the Vietnam hangover to the post-Cold War period of dominance. Designed in light of the lessons of Vietnam, at a time where tactical aviation was taking control of the US Air Force, the F-15 outperformed existing fighters and set a new standard for a modern air superiority aircraft. Despite repeated tests in combat, no F-15 has ever been lost to an aerial foe. The production line for the F-15 will run until at least 2019, and longer if Boeing can manage to sell anyone on the Silent Eagle.In the wake of Vietnam, the United States needed an air superiority platform that could consistently defeat the best that the Soviet Union had to offer. The F-15 (eventually complemented by the F-16) provided this platform, and then some. After the end of the Cold War, the United States needed an airframe versatile enough to carry out the air superiority mission while also becoming an effective strike aircraft. Again, the F-15 solved the problem.And it’s a plane that can land with one wing. Hard to beat that.A Contest Based on ParametersAgain, this exercise depends entirely on decisions about the parameters. A different set of criteria of effectiveness would generate an entirely different list (although the F-15 would probably still be here; it’s invulnerable). Nevertheless, the basic elements of the argument are sound: weapons should be evaluated in terms of how they help achieve national objectives.Honorable mentions include the North American Aviation F-86 Sabre, the Fokker D.VII, the Lockheed-Martin F-22 Raptor, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the Supermarine Spitfire, the North American Aviation P-51 Mustang, the McDonnell Douglas EA-18 Growler, the English Electric Lightning, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, the Sukhoi Su-27 “Flanker,” and the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines