#zoltan istvan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Zoltan Istvan Gyurko

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Transhumanist Party: Could It Change Our Political Future?

The noted transhumanist Zoltan Istvan recently published an article in the Huffington Post entitled: Should a Transhumanist Run for US President? Continue reading The Transhumanist Party: Could It Change Our Political Future?

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

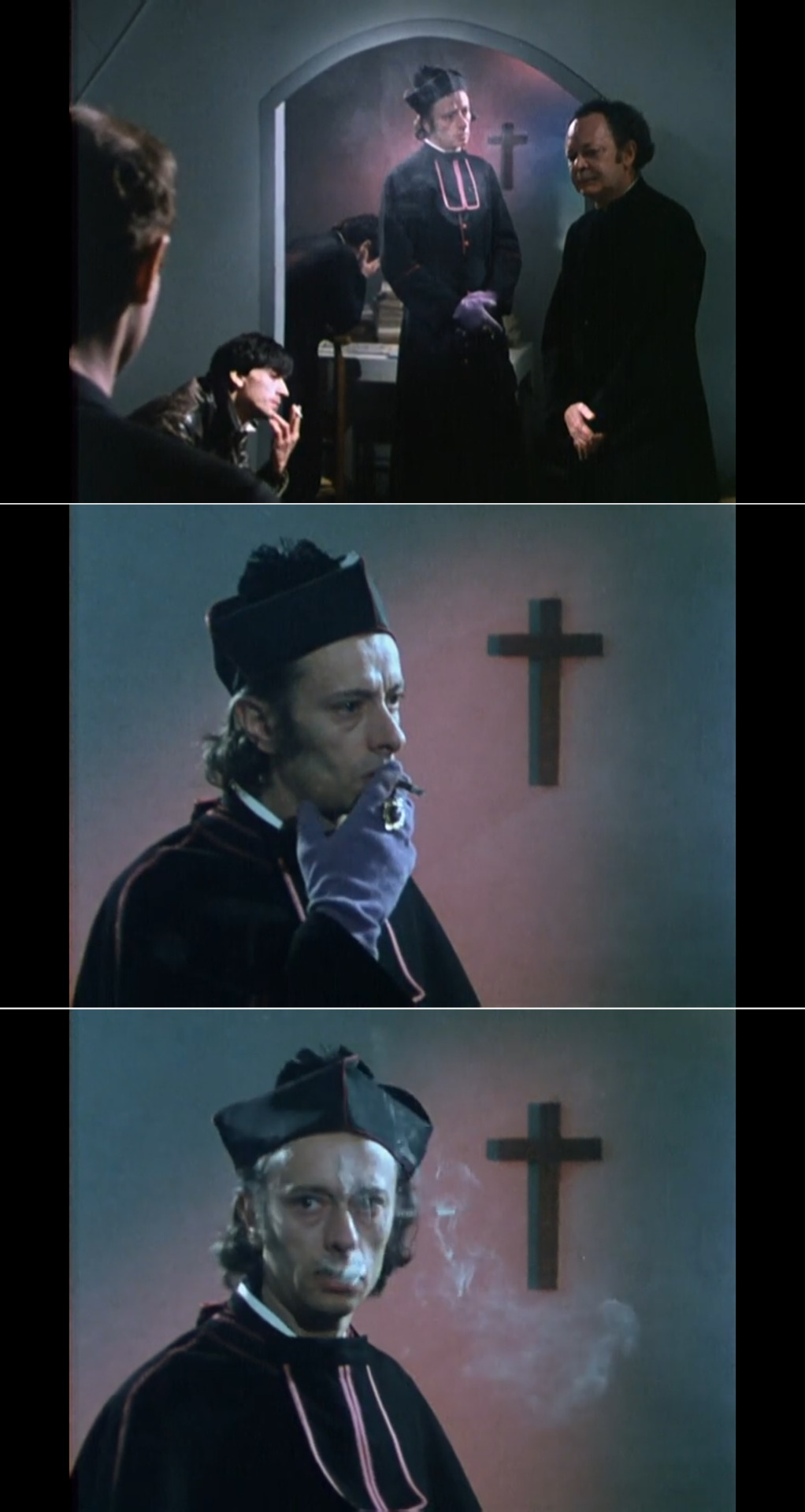

Screen captures from La vocation suspendue, directed by Raúl Ruiz, 1978.

--

Many transhumanists like (Ray) Kurzweil contend that they are carrying on the legacy of the Enlightenment — that theirs is a philosophy grounded in reason and empiricism, even if they do lapse occasionally into metaphysical language about “transcendence” and “eternal life.” As I read more about the movement, I learned that most transhumanists are atheists who, if they engage at all with monotheistic faith, defer to the familiar antagonisms between science and religion. Many regard Christianity in particular with hostility and argue that Christians are the greatest obstacle to the implementation of their ideas. In his novel, The Transhumanist Wager (2013), Zoltan Istvan, the founder of the Transhumanist political party, imagines Christians will be the ones to oppose the coming cybernetic revolution. Few Christians have shown much interest in transhumanism (or even awareness of it), but the religious right’s record of opposing stem-cell research and genetic engineering suggests it would resist technological modifications to the body. “The greatest threat to humanity’s continuing evolution,” writes transhumanist Simon Young, “is theistic opposition to Superbiology in the name of a belief system based on blind faith in the absence of evidence.” (...)

In the late 19th century, a Russian Orthodox ascetic named Nikolai Fedorov was inspired by Darwinism to argue that humans could direct their own evolution to bring about the resurrection. Up to this point, natural selection had been a random phenomenon, but now, thanks to technology, humans could intervene in this process. “Our body,” as he put it, “will be our business.” He suggested that the central task of humanity should be resurrecting everyone who had ever died. Calling on biblical prophecies, he wrote: “This day will be divine, awesome, but not miraculous, for resurrection will be a task not of miracle but of knowledge and common labor.” He speculated that technology could be harnessed to return Earth to its Edenic state. Space travel was also necessary, since as Earth became more and more populated by the resurrected dead, we would have to inhabit other planets.

Fedorov had ideas about how science could enact the resurrection, but the details were opaque. The universe, he mused, was full of “dust” that had been left behind by our ancestors, and one day scientists would be able to gather up this dust to reconstruct the departed. Another option he floated was hereditary resurrection: sons and daughters could use their bodies to resurrect their parents, and the parents, once reborn, could bring back their own parents. Despite the archaic wording, it’s difficult to ignore the prescience underlying these ideas. Ancestral “dust” anticipates the discovery of DNA. Hereditary resurrection prefigures genetic cloning.

This theory was carried into the 20th century by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit priest and paleontologist who, like Fedorov, believed that evolution would lead to the Kingdom of God. In 1949, Teilhard proposed that in the future all machines would be linked to a vast global network that would allow human minds to merge. Over time, this unification of consciousness would lead to an intelligence explosion — the Omega Point — enabling humanity to “break through the material framework of Time and Space” and merge seamlessly with the divine. The Omega Point is an obvious precursor to Kurzweil’s Singularity, but in Teilhard’s mind, it was how the biblical resurrection would take place. Christ was guiding evolution toward a state of glorification so that humanity could finally merge with God in eternal perfection. By this point, humans would no longer be human. Perhaps the priest had Dante in mind when he described these beings as “some sort of Trans-Human at the ultimate heart of things.”

Meghan O'Gieblyn, from Ghost in the Cloud - Transhumanism’s simulation theology, for n+1, Issue 28 : Half-Life, Spring 2017.

0 notes

Text

Kristan T. Harris Hosts American Journal on Infowars, Magic Behind Words, Post Genderism

Guests Ryan Gable, Zoltan Istvan

Check out this episode!

#news#trends#technology#futurism#politics#history#art#robotics#transhumanism#rundown live#the rundown live#philosophy

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Quote

China keeps me up at night. Over the last 10 years, China has been taking over the field of radical science and technology — and their population is four times ours. They are winning the AI and genetic editing races, in my opinion — which are the most important technologies of the future. We need to always remember — they are not a democracy. If they grow to be the world’s largest power, then Earth may become an authoritarian-influenced world. America must stop China from becoming so powerful. We must remain competitive against them. Otherwise the future will belong to a culture that is foreign to the West.

Zoltan Istvan, “Transhumanism, Universal Basic Income, And A Republican Named Zoltan” (November 26th 2019).

#UBI#Universal Basic Income#Basic Income#Transhumanism#genetic engineering#Zoltan Istvan#Zoltan Istvan Gyurko#2020 presidential race

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

'They live, they don't live, see what happens.' Said the President of those who get sick while we #StayAtHome. I am confused on the detail of the projected timeline, a couple of days ago it was said in a meeting at the Whitehouse that it will take 30 days to produce ventilators, and I thought that was the plan, countries produce as many ventilators as soon as possible then go forward with a plan from there. Now however there is talk of reopening the US economy by upcoming Easter Sunday, a timeline at odds and not in line with the amount of closure time seen in Wuhan. Meanwhile, @zoltan_istvan is blogging on @Medium and blurbing on @Instagram about potential suicide brought about this #PandemicEconomy, he encourages #ReopeningTheEconomy as well. While the transhumanist and former presidential candidate predicts death being brought about by the pandemic the only public persona or influencer of sorts who has come close to sounding even remotely dystopian in tone was Glenn Beck as he talked about how older Americans should return to work: “Even if we all get sick, I would rather die than kill the country. All of this seems very strange, except for the fact that Mr. Istvan has taken to Medium to post his articles, somehow a step of maturity and professionalism more than having a blog on @WordPress. All of this I find very interesting and odd to have been said during a time of international distress, but it is understandable that for some of us 'you can't not say nothing all the time.' "As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord." Joshua 24:15 Which to me currently means staying healthy as possible, by any means possible so that all members of society can survive at all costs. The only way I know of to fulfill and adhere to the survive at all costs mantra is to do what most governments and scientists are saying and stay at home, which if it takes a minimum of 30 days to produce ventilators will be longer than Easter Sunday, but for now, there is not much to do other than wait and see.

@thejdw81

#live#see what happens#wait and see#pandemic economy#zoltan istvan#medium#blogging#blurb#instagram#reopening the economy#stay at home#open by easter#easter#timeline#wuhan#whitehouse#president#transhumanism#futurism#futurist#wordpress#glen beck#die for the economy#get sick#got sick#ventilators#breathing machines

1 note

·

View note

Link

Well this doesn’t sound at all nightmarish.

https://projects.qz.com/is/the-world-in-50-years/expert/1690898/

Too bloody right

Yeah erm actually no thanks

#TheyWillNotWin

#mary harrington#twitter#twitter thread#quartz#zoltan istvan#maybe the amish are right#artificial intelligence

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Transhumanist Thought Leader Zoltan Istvan

Guest:

Zoltan Istavan

The People's Basics is on Linktree

Note from the chairman: I love the idea of liberty and bodily autonomy as long as it's not unduly threatening others' security. I'm pro transhumanism but I think it should be evaluated on a more case by case basis.

0 notes

Link

“I don’t think we should have people live for a very long time,” Musk says in a WELT Documentary interview. “It would cause ossification of society because the truth is, most people don’t change their mind; they just die. And so if they don’t die, we’ll be stuck with old ideas, and society won’t advance. I think we already have quite a serious issue with the gerontocracy, where the leaders of so many countries are extremely old. Look at the U.S.—its very ancient leadership. It’s just impossible to stay in touch with the people if you’re many generations older than them.”

My first thought, hearing this argument, was to admit that there is some truth to it. My next thought was a snarky one: One would think, with this view, Musk would spend his valuable time on Twitter railing against bad policy ideas developed by elderly politicians, but, in fact, he tends to focus on the excesses of the woke. And guess who leads the charge on that? Certainly not the gerontocracy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m reading The Transhumanist Wager right now and it’s hilarious

Our hero’s name is Jethro Knights, and he’s like every incel icon ever. He only views people in terms of how he can use them, he violently assaults people, he talks back to his professors, and his “calm cool reason” is so lonely in a sea of other people’s emotions.

This whole thing is a bad self-insert fiction, where only Jethro is right and everyone else is stupid. It’s a classic straw-man argument for transhumanism. And it’s not even written that well - so much exposition, not enough plot or characters.

But at the very least, the lack of self-awareness is funny.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog #3: Zoltan Istvan is Probably Going to Die One Day and That's Kinda Sad but I don't Care Enough to Bring about Real Change so Whatevs

Damn, I posted one poem in the whole week; that's a new low. In my defense, I was trying to get hired and I was performing cunnilingus and I was doing lines of crystal meth and not at all having multiple, sequential, identity crises and other shit that certainly happened and is not construed incorrectly at all. Here's a compensatory haiku, because I feel bad that the people who don't follow me (at least leave a comment about how much you hate my poetry ya lazy pricks) got such little content

The Story of a Man Who is Glad that he Wears Glasses:

I watch God's grand sky

An angel returns my gaze

Oh wait that's bird shit

Radical Thought of the Week: God doesn't exis... wait I already knew that.

Actual RTotW: Because of the subjective nature of our perception of events, and the absence of absolute truth (due to the nature of reference frames) reality is, in fact, subjective and therefore not provable. This means that reality is in fact not real.

Poet of the Week: Charles Baudelaire

Person of the Week: You probably read the title and it's Zoltan Istvan cause mortality is for people who believe in religions and that's kinda dumb so let's be immortal even though that is probably not even close to possible given our current technology but a disembodied Internet voice can dream ya'know.

Religion of the Week: These motherfuckers https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/União_do_Vegetal

Diety of the Week: Walmart

Place of the Week: Yugoslavia

Political Party of the Week: The coalition that just got into the Italian PM's office gratz to you guys or something idk

Sexuality of the Week: Stultasexual, (from stultus, Latin for stupid) a sexual attraction to mainstream media outlets like Fox and CNN

Song of the Week: Angel of Small Death and Codine Scene, Hozier

Miscellaneous Thing of the Week: Last week, because it was probably better

1 note

·

View note

Text

Evictionism, transhumanism and abortion

https://youtu.be/D06j3awJnik

youtube

0 notes

Text

The Rundown Live #882 - Zoltan Istvan, Bionic Hybrids, Brain Cloud Interface, Synthetic Biology

The Rundown Live #882 - Zoltan Istvan, Bionic Hybrids, Brain Cloud Interface, Synthetic Biology

Check out this episode!

#news#trends#technology#futurism#politics#history#art#robotics#transhumanism#rundown live#the rundown live#philosophy

0 notes

Text

damnation follows any attempt to recover paradise

A while ago, I read Mark O’Connell’s 2017 book To Be a Machine, in which he investigates the transhumanist project of achieving a merger of the body and technology that allows the body to live forever—and, essentially and paradoxically, to fall away, to become a nonfactor, so you can experience yourself as pure consciousness. It’s like, if the average human wavers in the Cartesian split between mind and body, uncertain, transhumanists break the impasse by betting firmly on mind.

The book is thoughtfully constructed. All the major transhumanist figures you hear about appear: Ray Kurzweil, Aubrey de Grey, Zoltan Istvan, Peter Thiel, Nick Bostrom. And O’Connell covers many facets of the transhumanist movement. He discusses life extension and cryonics; “whole brain emulation,” or the creation of a mind independent of any corporeal “substrate,” like the brain, which could feasibly be downloaded into any number of different bodies or substrates altogether; the possibility of artificial ultraintelligence, and the corresponding activism in the face of the existential risk such AI poses to humanity; the augmentation of the human body, as pursued by corporations and the state and military and as pursued by the laypeople and amateur biohackers known as “grinders”; and the idea that we could within our lifetimes reach “longevity escape velocity”—the magical point at which the science of life extension has advanced far enough that it’s easy to access and take advantage of and the relationship between how old you are and how likely you are to die becomes irrelevant.

It’s all shot through with a few major themes. One is the battle transhumanists wage versus “deathism,” their term for what they believe their critics suffer from, namely a need to protect yourself from death by trying to convince yourself it isn’t terrible. And two, transhumanism as but the latest incarnation of an age-old religious impulse: the desire for transcendence and eternal life—now, through technology, as before through religion.

I had such strong feelings of anger and contempt for the transhumanists after reading it, though. Maybe I’m guilty of being “deathist”: perhaps I mask my terror of death by pretending I’m okay with the fact that I’ll experience it. It’s certainly true I haven’t confronted death as closely as, say, Roen Horn—a young man who accompanies Zoltan Istvan in his campaign bus as his assistant during Istvan’s bid for the 2016 presidential nomination as the Transhumanist Party candidate, who came to transhumanism after a terrible childhood accident made him nearly bleed out. And it’s a clever move on O’Connell’s part to characterize Horn as he does. Initially, Horn seems a textbook incel type—being twenty-eight and so convinced a woman would cheat on him that he’s never pursued a relationship. But then O’Connell reveals the fact of the accident and the “darkness” it reveals to Horn, the “black terror beneath the thin surface of the world,” and that makes you realize why Horn is frightened by death as he is. It’s harder to dismiss him after that.

Transhumanism often seems the result of such extreme near-death experience. Tim Cannon, one of the grinders O’Connell writes about, had experiences of addiction that reduced his lived condition to its animal essence—making him beholden to his body, all urge and impulse beyond his own conscious control—in ways that left him desperate to hack it and transcend it. And Laura Deming, founder of the Longevity Fund, a VC firm focused on life extension technology—and all of twenty years old when O’Connell speaks to her—reports being rattled to her core by watching her grandmother die. The experience brought her to understand there’s a bodily decay in store for her and everyone she knows that she can do nothing to stop. And it leaves her obsessed with extending the human lifespan as the “correct” thing to do.

But it's only children who fear death in as total and paranoid a fashion as Deming or Cannon seem to. And at some point, children grow up. They become adults. They come to understand death as an inevitability, even if that’s only in the abstract. They come to realize it’s death that gives the time we are alive its meaning. They don’t need to denigrate the human body by sneering that people are mere “monkeys,” as Cannon does. They don’t live in atavistic terror of aging as do Deming or Aubrey de Grey (who leads the transhumanist group SENS, or Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence). And they devote their time and attention to curing the ills that plague the world now, rather than fixing their eyes on projects like defeating death. Or creating colonies in outer space—which seems driven by a similarly childish zeal on the parts of people like Peter Thiel, if one that’s less terrified—and bringing on the Singularity, the point, predicted by futurist Ray Kurzweil, at which the merger between humans and technology becomes so complete that technology’s evolution entirely supersedes human evolution.

“To the charge,” O’Connell writes, “that such a merger” between human and machine “would obliterate our humanity, Kurzweil counters that the Singularity is in fact a final achievement of the human project, an ultimate vindication of the very quality that has always defined and distinguished us as a species—our constant yearning for a transcendence of our physical and mental limitations.” When I read those lines, I wanted to yell at Kurzweil: The yearning to transcend our physical and mental imitations is not meant to be fulfilled! I remember scribbling that line in my notebook on the train home from work just as I heard a man in the seats across from mine telling his seatmate about the intense cancer treatments he was going through. And that’s bravery to me. That’s what I admire: the ability to face the fact of the body’s fragility, rather than looking to obliterate it.

Sometimes I found myself thinking that the transhumanists, driven by greed (to experience, to colonize) and fear (of death, so childish in its intensity) were deformed people. I know this isn’t a good word to use. But I wasn’t a good person I was reading this book. I could feel my heart turn in revulsion as I encountered all these people who treated being alive, finite, human as a problem to be solved. The chapter on the grinders, “Biology and Its Discontents,” was particularly trying. When O’Connell reveals that Tim Cannon, deep in his alcoholism and spiraling, had once tried to kill himself, for a vicious instant I thought, If only he had succeeded. I just couldn’t take his sneering contempt—his saying, so often, things like, “People want to stay being the monkeys they are. They don’t like to acknowledge that their brains aren’t giving them the full picture, aren’t allowing them to make rational choices. They think they’re in control, but they’re not.”

There’s this moral superiority there. This assumption that you’re better than other people; other people are idiots, and you alone are stripped of illusion. I hate that—that loathing for your fellow man’s fallibilities as though you yourself have none. I hate that more than anything.

What’s more, I hate the apparent lack of regard for consequences on the part of so many transhumanists. In her book Being Numerous, Natasha Lennard writes about Paul Virilio’s notion of the “accident”: that “which is contained within, and brought into the world by, the inventions of progress […] itself.” In other words, when you invent a plane, the possibility of a plane crash follows. Often the transhumanists seem entirely unconscious of the possibilities their tech is bringing into existence. That’s simply outside the scope of their narrow remit. When Randal Koene, who runs the whole brain emulation organization Carboncopies, is confronted with the possibility that the downloading of minds to different substrates might unlock an entirely new level of invasive advertising, he basically shrugs it off. In that, he’s like just about everyone O’Connell talks to, every tech billionaire and devotee of any renown in our horrible historical moment: in love with the possibilities, unconcerned with the consequences.

Just because the possibility of developing a certain type of technology is there doesn’t mean it needs to be done. Where is the restraint? Maybe that’s longer a virtue in a late capitalist society, after the end of history, in a time when we don’t have any overarching societal narrative that would make restraint something to want to practice or that would make some notion of the human something we want to consider before we eradicate it. In this world we live in, everyone, atomized, pursues their own ends. What you want, what’s possible, and what you have the means to make possible are the only standards by which a decision to act is made.

Most of the transhumanists are frighteningly cavalier, to the layperson of a humanist bent like me, about the stages of the revolution they foresee. Ray Kurzweil, for one, talks about the trajectory he’d like to see so casually. “What would be a nice scenario is that we first get smart drugs and wearable technologies. And then life extension technologies. And then, finally, we get uploaded, and colonize space and so on.” And so on. Again, reading that line, I wanted to yell: Nothing entitles you to space! Have we not learned not to colonize?

It all speaks to the experience of reading To Be a Machine, which is this kind of Mobius strip of revulsion (“hell no”) and relenting (“I mean, maybe” or “well I guess” or “am I the problem here?”). At one point, O’Connell drops a quote from D. H. Lawrence: “science and machinery, radio, airplanes, vast ships, zeppelins, poison gas, artificial silk: these things nourish man’s sense of the miraculous as magic did in the past.” And it’s like “miraculous” is one side of a coin whose other side is “horrifying,” and O’Connell spends the entire book flipping that coin as he talks impartially about the transhumanist movement, showing you first one face of it and then the other.

It's a credit to O'Connell that he could stay as evenhanded as he is reporting on these people. I even came to dislike his repeated tendency to express fond, largely tolerant and even feelings toward people who sounded as inhuman and afraid of life as Roen Horn did. Maybe I was disappointed I couldn't be as gracious as he was even though I like to consider myself a kind person who's inclined to empathy.

Or more likely it’s because I lack O’Connell’s proximity to religion. Ultimately, his ethos of impartiality comes from being able to so clearly see the parallels between transhumanist and religious desire. This is a parallel that I, not being a religious person at all, having no real religious instinct, would never have felt so intuitively or described so convincingly. It leads O’Connell to afford the transhumanists the same respect he would the devotees of any other religion. As he’s listening to Tim Cannon share his vision of eventually being not a body but simply a “series of nodes” peacefully exploring the universe for all time, he writes

I was going to say that all of this sounded hugely expensive; I was going to ask who was going to pay for it all. But I thought better of it, in the way that you might think better of making a joke about the central tenets of a person’s faith after they had taken the trouble to explain them to you.

And transhumanism is ultimately a faith: a contemporary reflection of the ancient desire to be delivered of the body, redeemed of its weakness and sin, no longer subject to its curse. The Singularity—however that is defined, whatever particular perfect union between human and machine a particular transhumanist aims for—is the Rapture. The world after this Singularity, affording as it does answers to all scientific questions and cures for all diseases, will be Eden.

And everyone in this book believes themselves to be among the elect.

And if, as the transhumanists believe, humans are effectively computers, in the way their minds operate—just with substrates made of meat—it’s also the destiny of obsolete technology to die. And so it is just for humans to wipe themselves out to usher in cyborgs and AI and superintelligence. It’s just technology, drawing all the way from the first spear a human being ever threw, achieving its teleological end.

But—as O’Connell also points out, the attempts religion has made to make good on its own teleological narratives tell us that damnation always follows any human attempt to recover paradise.

#books#literary#nonfiction#mark o'connell#ray kurzweil#aubrey grey#laura deming#tim cannon#zoltan istvan#peter thiel#transhumanism#the singularity#the end of history

0 notes