#zenkyoto

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nishikido Ryo for GQJapan 2023.06.23 in Dior

rough translation of his interview below

GQJapan Interview with Nishikido Ryo for Netflix Series "Let's Get Divorced "I wondered if it was okay to live more selfishly".

We interviewed Nishikido Ryo, who returns to tv dramas after a four-year absence to act in the role of a man who is playing both of the main characters in "Let's Get Divorced," which has been available exclusively worldwide on Netflix since June 22 (Thursday). He talks at length about everything from the appeal of the character Kano Kyoji to "What is true coolness?”

Actor Nishikido Ryo is back.

In the Netflix series "Let's Get Divorced", a new member of parliament, Shoji Taishi (Matsuzaka Tori), and a national actress, Kurosawa Yui (Naka Riisa), who play a friendly couple for the sake of public appearances, overcome various obstacles and work together to achieve their goal of "getting a divorce". Nishikido plays Kano Kyoji, a "sexy self-styled artist" who meets Yui by chance and becomes close to her.

His presence brings a thrill to Yui, who has grown tired of their married life, as he goes to play Pachinko every day and creates mysterious "artworks" in his garage-like home, which he calls his studio. Yui says that he is "a person who’s alive yet dead." He is uninhibited in what he says and does, and is certainly a man of a certain sex appeal.

This film was co-written by Kudo Kankuro and Oishi Shizuka. They did not write one story each, but rather took turns writing a little bit at a time, as if they were exchanging diaries. Kudo-san said of Kyoji, "I wondered if women find that kind of thing sexy. To be honest, I had no idea, so I'm glad Oishi-san wrote it for me (laughs). I understood now that it’s onscreen.” Oishi, on the other hand, said, "He’s like a Zenkyoto (a radical student leftist) man from a generation older than mine. It may not be the kind of character that scriptwriters today would write, but the older generation liked that kind of character" (both from press materials).

Indeed, the character has the air of an 'outcast hero' from a Showa-era girls' manga. How did Nishikido himself see the appeal of such a character?

“I think it's about not being influenced by your surroundings. I like what I think is good, and I am interested in what I am interested in, but not in what I am not interested in. With so much information available on TV and social networking sites, I think it's quite a difficult thing to do, and it makes you feel insecure. But Kyoji is not afraid to be true to himself. Or rather, he probably doesn't even think about how he is seen.”

What is true coolness?

There is a scene in the film where opposition MP Go Soda (Yamamoto Kōshi), who is the candidate opposing Taishi, gives his best speech and the audience is engulfed by it, when Kyoji, who is present, clearly points out Soda's misstatement. This scene shows what is at the core of this seemingly free-spirited man. He is aloof, but has a passion lurking deep within him. This part of him is so compatible with the image of Nishikido himself that I feel that no one else could have played the role but Nishikido. When I told him this, he said, "Really? I'm glad to hear you say so.”

“Of course I hoped that Kyoji's coolness would be attractive, but that doesn't mean I should try to make myself attractive or act sexy. It would be very embarrassing/cringe-worthy, the moment it is found out. I was performing while praying "I hope it looks like that."”

By the way, there are several scenes in the drama where Kyoji smokes, and it is said that Nishikido's suggestion was used in one of the scenes.

“When they asked me what to do after smoking outdoors, I said, 'Why don't you put it out on the soles of your shoes?' You can't litter, and it wouldn't be cool to step on it and pick it up. It's not really an idea, though.”

The relationship between Yui and Kyoji eventually becomes known toTaishi, and the two confront each other directly towards the end of the story. Born and raised in a political family, Taishi exchanges words with Kyoji, a type he has never met before, and honestly admires him, saying 'You have something I don't have' and 'You are endlessly free, amazing'. But after he leaves, Kyoji throws the paper cup he was holding onto the floor.

“It's amazing that Taishi would come to that place, isn’t it? Kyoji probably already felt defeated at that point. He (Kyoji) thought he was going to bite him, but he didn't. Because Daishi probably didn't even think he was bitten, and he probably left without even realising he had won, right?"

After saying this, Ryo added, in typical Osaka fashion, "I don't know!" he added with a laugh.

“I don't really know. Ah, I just know that when I saw the video of that scene, I thought to myself, "I'm so tiny”. The sense of scale with Taishi was just too different. (Laughs)”

When I ask him “Who do you think is cooler, Taishi or Kyoji?” he said "They are both cool, aren't they?"

“Sorry for the half-assed answer, but .......I think each of them have their own cool and bad parts, not just the two of them, but everyone in this piece is cool in their own way. I thought Yui, Henry, and Yui's manager all had their own coolness.”

I want to have fun doing fun things.

Kyoji's attitude of knowing who he is & doing what he wants, which is the basis of his coolness, is also something that is quite difficult to maintain while living in society. Were there any parts that resonated with you?

“I myself can say that I am living as I please, or I should say, I am living the life I want to live. It is not that I am only doing what I want to do, but I think it is okay to live more selfishly, and I have come to value my time more”

As noted at the beginning of this article, this is the first time in four years that he has appeared in a drama. In addition, among the dramas in which he has appeared in the past, Ryusei no Kizuna (2008) and Gomen ne Seishun! (2014), which, like this drama, was written by Kudo Kankuro and produced by Isoyama Akira, and both were directed by Kaneko Fuminori.

“When I was working on 'Ryusei no Kizuna', Kaneko-san kept telling me to 'be careful with my enunciation” I thought I was speaking clearly. When I met him for the first time in a while in Gomen ne Seishun, I was told that my speaking had improved a lot. I think he said that once or twice this time, too. He only praised my fluency (laughs)."

Producer Isoyama, who was present at the interview, added, "Of course, that's not all. (Director Kaneko) was very complimentary, saying 'You thought it through very well’.” To which ryo replied "I ‘m embarrassed that he thought so! It's so lame” He exclaimed in agony.

“I just didn't happen to have any chance in the past four years, so I didn't really feel that I had a gap in my drama career. Now that I've been approached, I just want to do my best, and if I'm invited to do something like this, I want to go anywhere. Not only in acting, but I also want to enjoy myself while doing things that look like fun.”

He goes where his heart takes him - to be happy, comfortable and free. It is this lack of self-consciousness that attracts and holds people's attention.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

; a little madness in the spring (bokuaka, 70k words, complete)

Tokyo, 1968. Akaashi Keiji has just enrolled in his first year of university, and the experience hasn’t been exactly what he had in mind. Bokuto, on the other hand, struggles to find his place in a world dominated by academics. Together they will end up joining the student revolutionary group Zenkyoto, which will also help them realize that there’s more to life than fighting for what they think is right.

also features: sidepair kuroken ; a fair amount of anti-war propaganda ; the haikyuu boys as les amis de l'abc wannabes in the twentieth century.

#we just finished uploading this one and we're v v proud!#bokuaka#haikyuu!!#bokuaka fic#bokuto x akaashi#histfic#ao3#akaashi x bokuto

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If we examine the case of the Todai Zenkyōtō movement discussed earlier, the Zenkyōtō confronted power by occupying the point of production this space of knowledge-production that we call the university. It obviously recalls for us the syndicalist understanding of worker-led factory occupations. While the university-wide Zenkyōtō base was comprised of the individual Zenkyōto organizations of each department, it also included activists from the Marxist-Leninist sects, numerous activists of the so-called "non-sect" radicals, and various small, relatively loose groupings. These were encompassed within the movement as part of the council-form known as the All-Campus Joint Struggle League. As its membership was not fixed or set, it experienced intense volatility and fluctuation in terms of individual comings and goings. Within each university, alongside the Zenkyoto radicals existed their opposition, Minsei (the JCP youth organization), as well as numerous organizations of the general student population who were unilaterally opposed to the struggle itself. At Todai, for instance, these organizations joined with the general student population at university assemblies to determine individual department policies. In such sites, violence was taboo, so decision making was supposed to remain at the level of a discursive war. The student assemblies in each department would incessantly and endlessly repeat again and again these discursive struggles, often lasting until the next morning. Far exceeding in numbers, the necessary quorum to fulfill protocol, these assemblies became in reality open to the participation of the entire student body. For the Zenkyoto movement, this intricate and complex war of discourse was an experience that bore close resemblance to what Arendt famously called "the emergence of political space."

The Zenkyöto movement was a student rebellion that broke from the prior style of postwar Japanese political movements. But it was not only this. The liberation of the concept of rebellion [hanran] from the theoretical framework of revolution was also a fundamental paradigm shift from the traditions of the revolutionary movement. The various party formations of the Japanese New Left generally saw themselves theoretically as vanguard parties, inheritors and successors of the Marxist tradition; that is, they saw themselves as the Marxist-Leninist party. This is the source of the sectarian literary style, beginning with the party program. Within the movement, each individual struggle (ein Kampf) must be positioned as merely one means in a connected chain leading to the final, ultimate revolution [der Kampf], the movement-form aimed at by the entire national political struggle. Here, the vanguard party is understood as the "headquarters," the order-giving division, of the mass movement, which must independently be a steadfast and strong community of revolutionaries. This is the logic of vanguardism. Yet, at the time, the "new vanguard parties" were tiny in comparison to the working class or even to the Communist Party, so they resorted to another self-determination: the Marxist-Leninist "left opposition." These characteristic "revolutionary parties" were an extension of the 1960 Anpo struggle, and when they encountered the Zenkyötö movement, they quickly became influential members and organizers. The composition of the Zenkyōtō as a group was an amalgamation of the masses in rebellion and the various sectarian formations. This produced a constant flux within the Zenkyōtō movement, the sects, and the masses from vanguardism to mass-movementism and vice versa. The revolutionary parties had now experienced a mass rebellion, a moment of insurrection.

However, in Japan, this term "rebellion" [hanran] brings up, rather, associations with the rebellion of nationalists in the military, as in the famous 2-26 Incident of 1936.' For Marxist-Leninists, it recalls perhaps the "counter-revolutionary" Kronstadt rebellion. In short, it is not exactly a positive term for political movements of the left. What Japanese revolutionaries experienced in '68 compelled them to fundamentally reconsider the history and theory of prior revolutionary movements. Precisely through this experience, Marxism itself was subject to close scrutiny. Since the Japanese '68, mass political movements have largely disappeared, and since the 1990s and the implosion of the socialist system, the interest in Marx or Marxism-Leninism has also largely been lost. There are scarcely any traces of the New Left sects of '68. Yet what cannot be destroyed, eliminated, or forgotten from our actual moment is the fact that this concept of rebellion was liberated from the tradition of revolutionary politics, this concept that exerted such a force on the theoretical experience of 1968. It transformed the style, the grammar, of revolution."

- Hiroshi Nagasaki, "On the Japanese '68," in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese '68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 28-29

#zenkyötó#new left#1968#japanese 68#hiroshi nagasaki#university students#university rebellions#radical history#japanese history#left history#academic quote#marxism#communism#vanguard party#student movement#japanese student movement#reading 2023#the red years

0 notes

Text

the winter of our discontent

Read this masterpiece on AO3 at https://ift.tt/SiBwTnx

by balconyscene

Tokyo, 1969. Iwaizumi Hajime doesn’t really believe in revolution, but meeting Oikawa Tooru, the newfound leader of the Zenkyoto movement, may prove him otherwise.

Words: 868, Chapters: 1/20, Language: English

Fandoms: Haikyuu!!

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: M/M

Characters: Iwaizumi Hajime, Oikawa Tooru, Akaashi Keiji, Bokuto Koutarou, Kozume Kenma, Kuroo Tetsurou, Ushijima Wakatoshi, Sakusa Kiyoomi, Sugawara Koushi, Tsukishima Kei, Yamaguchi Tadashi, Hinata Shouyou

Relationships: Iwaizumi Hajime/Oikawa Tooru, Akaashi Keiji/Bokuto Koutarou

Additional Tags: histfic, Historical AU, Enemies to Friends to Lovers, Eventual Fluff

read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/SiBwTnx

0 notes

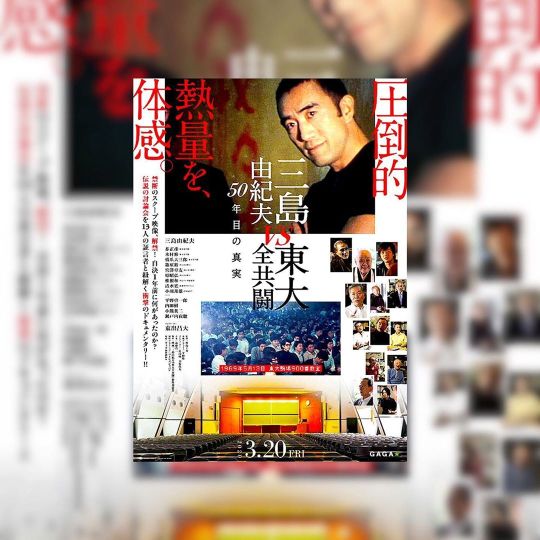

Photo

・ ・ #東京アラート発動中 #socialdistancing #tohoシネマズ日比谷 #復活 ・ 【今日の本命】 三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘〜50年目の真実〜漸く観れた。 非常に観て良かった! ・ お互いに元々は反米愛国主義で、ある意味“尊王攘夷”。幕末の薩摩と長州ではないですか! 楯の会と全共闘が共闘していたら、三島は龍馬にでもなり得たのか? 歴史にタラレバはない。だから、三島は共闘しなかった。右でも左でも勝てない事を知っていたのかなあ、三島は。 三島の自決から今年50年になる。早めに配信して冷めた日本人の熱量をアゲた方が良いと思いますが。 ・ #三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘50年目の真実 #mishimathelastdebate #豊島圭介 #東出昌大 ・ #三島由紀夫 #yukiomishima #楯の会 #tatenokai #芥正彦 #masahikoakuta #東大全共闘 #zenkyoto #小川邦雄 #tbs #瀬戸内寂聴 #jakuchosetouchi ・ #圧倒的熱量を体感 ・ #映画 #movie #cinema #ビバムビ #ınstagood #instamovie #instapic #moviestagram (TOHO Cinemas 日比谷) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBDQ_DQABAV/?igshid=wzv1j7rep7d

#東京アラート発動中#socialdistancing#tohoシネマズ日比谷#復活#三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘50年目の真実#mishimathelastdebate#豊島圭介#東出昌大#三島由紀夫#yukiomishima#楯の会#tatenokai#芥正彦#masahikoakuta#東大全共闘#zenkyoto#小川邦雄#tbs#瀬戸内寂聴#jakuchosetouchi#圧倒的熱量を体感#映画#movie#cinema#ビバムビ#ınstagood#instamovie#instapic#moviestagram

0 notes

Note

Hi there, nice blog. I was wondering if you can share some information about the wonderful and mysterious singer. Sad that she retired so early. RIP

Hello, happy new year and thank you so much.

Morita Doji (this is her artist name; her real name is unknown) was a Japanese singer-songwriter born in 1952, active from 1975 to 1983. She and her circle of friends were part of the Zenkyoto (All Schools Joint Struggle Committees) movement of the late 60s. After the death of one of these friends in 1972, she started making music under this artist name, keeping an enigmatic and anonymous appearance behind her trademark sunglasses and storm of curly black hair. Songs like "Our Failure" became the theme for the struggle and crushing of this generation. She gained a following for her music's unique existential directness, dark solitude and empathic ability. She would often be in tears as she sang her songs live. After seven albums she retired from music and disappeared completely from the public eye in 1983. Her music enjoyed some rediscovery/resurgence when "Our Failure" was featured as the theme song of a popular 1993 TV drama, "High School Teacher." This prompted a best of compilation album to be released which included an unreleased draft of the song, "The Sea Cries Out, You Can Die" called "Playing Alone." She passed away of heart failure in 2018. There is not a lot of information about her because she was very purposely self-effacing. There are rumours, bits of information people state as facts, certain information that has come to light which may or may not be true that I won't include here because apparently she did not even want her death to be publicly announced. Some of her inspirations come from the writers, Osamu Dazai, Kazumi Takahashi and manga artist, Yoshiharu Tsuge.

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

『討論 三島由紀夫vs.東大全共闘』より (1969) Yukio Mishima vs. University of Tokyo Zenkyoto members, Masahiko Akuta (and his baby)

#yukio mishima#masahiko akuta#Mishima-san is a loser#The All-Campus Joint Struggle Committees#film#60s#「右も左もあきまへん」って言ったのは誰だっけ

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I almost put "Yukio Mishima crushing bussy" at the bottom but that is less germane to the chain of events than the Zenkyoto riots

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Riot police at the University of Tokyo haul off a man wearing a white helmet, cuffed hands clasped above his bowed head. His expression is a mixture of resignation and defiance, but the fine details are hard to discern, obscured by the dark shades of the monochrome photograph he is depicted in — where he remains frozen in time. In the foreground, an officer is speaking into his transceiver, perhaps reporting back to the tactical unit in charge of operations or answering a query from other troops conducting a sweep of the campus.

Another image shows a protester propelling a Molotov cocktail from a balcony toward an approaching blast from a water cannon.

There are also moments of candor: An activist with his mouth full of an onigiri rice ball; students playing a game of go next to a bottle of Suntory whisky; and a man, fast asleep on the floor, with a butt-filled ashtray sitting by his elbow.

These are considered to be the only photographs from behind the barricades documenting the final months of riots that engulfed the nation’s top educational institution. The uprising culminated in a historic two-day showdown 50 years ago on Jan. 18 and 19, 1969, that saw the last occupants of the Yasuda Auditorium captured by police, marking the end to a decade of violent, and occasionally deadly, student protests.

“I didn’t really have any strong political views at the time,” says Hitomi Watanabe, a photographer who was granted sole access to shoot inside the auditorium at the time.

A graduate of the Tokyo College of Photography, she had been wandering the streets of Shinjuku, then home to the nation’s counterculture, snapping photographs of buildings, alleys and the workers who fueled the nation’s postwar economic boom.

Watanabe was also drinking buddies with artist Michiyo Yamamoto, often crashing at her flat near Shinjuku.

“Sometimes at night, Yamamoto’s partner, Yoshitaka, would return home. He’d simply acknowledge us and then just smoke cigarettes — he wasn’t a very talkative guy,” Watanabe recalls.

Then a postgraduate student at the University of Tokyo, Yoshitaka Yamamoto would soon be elected the leader of his university’s branch of Zenkyoto, the All Campus Joint Struggle League, and emerge as one of the central figures alongside Akehiro Akita, chairman of Zenkyoto’s Nihon University branch, in the student movement that swept across the nation.

“Yamamoto’s quiet but determined demeanor inspired me,” Watanabe, 73, says on a recent afternoon at a cafe in the Tokyo neighborhood of Oji.

“I began shooting his portraits,” she says, a project that would impact her life and career in unforeseen ways.

Read more...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WINTER OF OUR DISCONTENT

pairing: iwaoi (oikawa tooru × iwaizumi hajime).

word count: +50k.

status: complete, will be updated every sunday on ao3 (currently on chapter one).

rated: mature (cw: eventual smut, police brutality).

tags: histfic ; historical au ; enemies to friends to lovers ; eventual fluff ; violence ; canon-typical violence ; eventual smut.

summary:

Tokyo, 1969. Iwaizumi Hajime doesn’t really believe in revolution, but meeting Oikawa Tooru, the newfound leader of the Zenkyoto movement, may prove him otherwise.

link: https://archiveofourown.org/works/45515419/chapters/114524179

#iwaoi#iwaoi fic#iwaizumi x oikawa#oikawa x iwaizumi#histfic#work: the winter of our discontent#haikyuu#haikyuu fic

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by Hitomi Watanabe / 渡辺眸 from the series Todai Zenkyoto, 1968-69 東大全共闘 -われわれにとって東大闘争は何か- © the artist

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Protesta de estudiantes japoneses, Zenkyoto (全 学 共 闘 会議) con lanzas de bambú y sus icónicos cascos / cerca del parque Hibiya de Tokio / 21 de octubre de 1971

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolutionary_Communist_League,_National_Committee

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Nichidai Zenkyoto helmets | NATIONAL MUSEUM OF JAPANESE HISTORY

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

radical eschatology and 1Q84

i wrote this as a goodreads review, but i couldn’t fit the whole text there so this is the review in its entirety.

“‘lunatic’ means to have your sanity temporarily seized by the luna, which is ‘moon’ in Latin. In nineteenth-century England, if you were a certified lunatic and you committed a crime, the severity of the crime would be reduced a notch. The idea was that the crime was not so much the responsibility of the person himself as that he was led astray by the moonlight. Believe it or not, laws like that actually existed… I learned it in an English literature course at Japan Women’s University, in a lecture on Dickens. We had an odd professor. He’d never talk about the story itself but go off on all sorts of tangents.”

I think a lot of my writing on this site consists of meandering tangents, only obliquely related to the book at hand — though less useful and interesting than this literature professor’s in 1Q84. Either way I will stick to what I’m comfortable with here. I will start with why I read this obscenely large book. My high school friend who was recently married, hosted a birthday party at a new place he moved into in Etobicoke. I arrived half-an-hour late from the time it was supposed to start (according to Facebook), and was the first one there — which is some indication of the sort of company I keep. As I awkwardly sat around after a brief house tour, he poured me a drink, and we chatted about life and my terrible job. He suddenly exclaimed, “Oh, I almost forgot. There’s something I want to lend to you.” He skips up the stairs and comes back down with a large phone book. On its front cover: a face hiding behind the characters “1Q84” — maybe embarrassed by its bloated constitution. This will help you on your daily commutes from hell, he encouraged me.

I’ve heard that your first Murakami book has a good chance of becoming your favourite Murakami book. That was probably the case for me with “Kafka on the Shore”. I think that book put me onto Kafka, before I would later encounter him in the work of Walter Benjamin, Judith Butler, and his late communist ‘wife’, Dora Diamant. But subsequent Murakami books were not as satisfying for me. After reading Norwegian Wood, I decided to try and take a break from Murakami. I had grown a little weary of the Oedipal themes, and Murakami’s recurring Manic Pixie Dream Girl tropes. Around this time, my fourth-year college roommate discovered Murakami for himself, and his first encounter was through 1Q84. He loved it, but what a book to start with, I had thought at the time. I was impressed that he ploughed right through such an enormous millstone of a novel. (I was very intimidated by its size when my friend handed it to me, but got through it in surprising time. Having now read 1Q84, I realize it was actually a very fun book to read, and often quite difficult to put down, so it now makes sense.) Anyways, I was discussing these things with my roommate and another law student who was camping with us at Sandbanks Provincial Park — she also shared similar thoughts as mine on Murakami. Conversation wandered on to Junot Diaz, who she was much more approving of — this of course was before the #MeToo revelations about Diaz. How quickly tides can turn. (Especially when there are two moons in the sky.)

So something about the structure of 1Q84. I am told the first two books are structured after the two books of Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier” — each chapter alternating between Aomame (major keys) and Tengo (minor keys). In each book of Clavier, Bach cycles through all twelve tones, a prelude and fugue for each tone’s major and minor keys. So each of Murakami’s chapters in Book 1 and 2 corresponds to a Prelude and Fugue in Bach’s collection of pieces — 48 chapters in all.

I admittedly have a thing for Bach. I have a copy of Gould’s “Well-Tempered Clavier” on compact disc at home. It came in a package of random shit the novelist Tao Lin gathered together from his bedroom and sold online for like $30 on eBay. That is the sort of stupid stuff I wasted my money on as an undergraduate student. Among the zines, postcard sized art prints, manuscript pages from his edits of Taipei, and a copy of “Shoplifting from American Apparel” was a disc of Gould’s “Well-Tempered Clavier”. In one of the preludes and fugues, the disc is scratched, and makes these heavenly wobbling sounds as it skips, and I have grown quite fond of these parts. I also particularly love hearing the infrequent muffled hums of Gould behind his gas mask.

Book 3 of 1Q84 is structured after Bach’s Goldberg Variations. In the past couple years, I’ve listened to this composition likely more than any other, simply because it’s one of the few albums I happened to have downloaded on my phone. It’s Igor Levit’s studio recording of the Goldberg Variations along with his recording of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and Rzewski’s “The People United Will Never Be Defeated”. I thought it was a clever trio to package in an album. I also recommend Lisa Moore’s performance of other Rzewski compositions put out by Cantaloupe.

I am particularly fond of Rzewski’s “People United” because it recalls for me my first May Day march, where I chanted the Chilean song (from which Rzewski’s title is derived and his piece alludes to) with other people on the street marching on the way to Queen’s Park, while students shouted ‘ftp’ at officers lined on the sidewalk. I was supposed to march with a small contingent from Student Christian Movement, but couldn’t find them at Allan Gardens, so I marched near some York OPIRG students, and in front of a communist who was debating random people the entire march, haha. I had never seen so many anarchists and communists in one place at a time. They sure do like their black and red flags, haha.

This brings me to the next comment I wanted to make. I was curious about Murakami’s politics and I had a difficult time finding a decent write-up that focuses on this, because Murakami can come across as fairly apolitical, which I think is what his ‘bourgeois individualism’ (I use that term in jest) requires of him. Anyways, I stumbled across a series of blog posts made by a Trotskyist grad student that discuss how Japanese student movement comes up in almost every single novel by Murakami, and he discusses how the student movement was a significant segment of the political left in Japan during that time.

“Some brief highlights of the student movement’s history in Japan will suffice. After the end of the war, university students oriented to the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) took advantage of the new liberal atmosphere to rally for university autonomy, for the appointment of progressive faculty and administrators, and for a student voice in administration… In 1948, students from all over Japan inaugurated the All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Organizations (known by its acronym, Zengakuren) with a leadership largely from the Japanese Young Communist League… However the honeymoon between the students and the JCP was short-lived… The JCP had seen the American occupation as an opportunity to complete the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Japan, which had been the Moscow-ordained task of Communist Parties the world over during the Popular Front (1936-39) and then again after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, when Communists were allied with all “liberal,” “democratic,” and “peace-loving” forces, meaning those of the ruling class.

…Student radicalism reached even greater heights as the movement entered the 1960s… In militant actions organized by Zengakuren, thousands of students broke into the Diet building twice in 1960, forcing the cancellation of a state visit by US President Eisenhower and the resignation of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi with his cabinet. During this period Zengakuren’s leadership was largely drawn from the “Mainstream Faction,” which had originated the federation’s opposition to the JCP, however during the late 50s the leadership was briefly taken over by students from the Revolutionary Communist League (RCL), a group formed from JCP exiles after the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary, which was influenced by Trotsky’s writings and would affiliate to the Fourth International. By 1964, there were three different organizations taking the name Zengakuren: the JCP supporters, the Revolutionary Marxists (a Tokyo-based split from the RCL) and a unity faction.”

There’s a lot more the Trotskyist grad student blogger (the official title I have designated to this person) goes into, but he essentially concludes that:

“I believe at this point that I have made a solid case for why Murakami, whose early books on the surface are completely apolitical, take their starting point as the destruction of the Japanese student movement, though at no point is the movement itself exactly foregrounded.”

An an earlier conclusion in his first post:

“Based on conjecture from his novels, we can assume he was around the anti-Stalinist left concentrated in the Zenkyoto groups, though he has insisted that he was never a member of any particular faction. “I enjoyed the campus riots as an individual,” he writes. “I’d throw rocks and fight with the cops, but I thought there was something ‘impure’ about erecting barricades and other organized activity, so I didn’t participate… The very thought of holding hands in a demonstration gave me the creeps.”

…Since this is all I have till I learn Japanese, I will have to take his word that he always had a rather superior, hipster attitude toward politics, which is believable enough considering his status as a graduate of one of Japan’s most elite private institutions. And yet, there is something I see in his early novels that undeniably regrets the collapse of the student movement, no matter how much he resented the factions for “impure” organizational work.”

I think Murakami’s disdain for this sort of leftist hypocrisy comes through in a particularly memorable dialogue in Norwegian Wood (which the Trotskyist grad student blogger never mentioned for some reason):

"Have you ever read Das Kapital?"

"Yeah. Not the whole thing, of course, but parts, like most people."

"You know, when I went to university I joined a folk-music club. I just wanted to sing songs. But the members were a load of frauds. I get goose-bumps just thinking about them. The first thing they tell you when you enter the club is you have to read Marx. "Read page so-and-so to such-and-such for next time.' Somebody gave a lecture on how folk songs have to be deeply involved with society and the radical movement. So, what the hell, I went home and tried as hard as I could to read it, but I didn't understand a thing. It was worse than the subjunctive. I gave up after three pages. So I went to the next week's meeting like a good little scout and said I had read it, but I couldn't understand it. From that point on they treated me like an idiot. I had no critical awareness of the class struggle, they said, I was a social cripple. I mean, this was serious. And all because I said I couldn't understand a piece of writing..."

“...And their so-called discussions were terrible, too. Everybody would use big words and pretend they knew what was going on. But I would ask questions whenever I didn't understand something. "What is this imperialist exploitation stuff you're talking about? Is it connected somehow to the East India Company?' "Does smashing the educational-industrial complex mean we're not supposed to work for a company after we graduate?' And stuff like that. But nobody was willing to explain anything to me. Far from it - they got really angry. Can you believe it?"

“...OK, so I'm not so smart. I'm working class. But it's the working class that keeps the world running, and it's the working classes that get exploited. What kind of revolution is it that just throws out big words that working-class people can't understand? What kind of crap social revolution is that? I mean, I'd like to make the world a better place, too. If somebody's really being exploited, we've got to put a stop to it. That's what I believe, and that's why I ask questions.”

"So that's when it hit me. These guys are fakes. All they've got on their minds is impressing the new girls with the big words they're so proud of, while sticking their hands up their skirts. And when they graduate, they cut their hair short and march off to work for Mitsubishi or IBM or Fuji Bank. They marry pretty wives who've never read Marx and have kids they give fancy new names to that are enough to make you puke. Smash what educational-industrial complex? Don't make me laugh!”

This passage actually reminds me of a Japanese exchange student I met as an undergraduate who was really into Murakami and used to perform folk music in her spare time. Even though she was an atheist or agnostic of some sort and really into gender studies, she used to attend an international students bible study that I used to go to at a friends’ house. She’s now doing a PhD at MIT in neuroscience, but that passage in Norwegian Wood always reminds me of her. Anyways, you can see how Murakami’s purity politics requires of him a rejection of fully embracing any comprehensive political or religious system. The individual is always of most importance to him, and I think that comes through in 1Q84 too.

Part of what gets to Murakami I suppose is the pretence involve with a lot of armchair leftists. It recalls for me a passage I read in a book about country music of all things called “The Nashville Sound” by Joli Jensen:

“Students rarely ventured into the Rose Bowl. When they did it was usually to be rowdy and to make fun of the rednecks. One night, as I was waiting tables, four fellow graduate students came in. They did not see me, and I watched in rising fury as they sneered and whispered and laughed among themselves at the people around them. These were my peers, who defined themselves as Marxists and had disdained me as a politically unsophisticated liberal humanist. They patronized me in class and were now in "my" world making fun of "my" friends. Shaking with rage, I went over to the table to take their drink order. Of course, they were stunned to find me working there, complete with sequined Rose Bowl vest, and they left immediately. I had caught them at an unseemly game. But I have come to wonder about the basis for my rage and about what it tells me about how we understand ourselves in relation to our perceptions of others.

At the time I felt superior to them, friends of the working class, indeed! and virtuous in my admiration of, and affection for, Rose Bowl patrons. Later, I began to wonder, was I really any better, turning the Rose Bowl into a mythical venue of "salt of the earth" authenticity? Is it really better to idealize and sentimentalize difference than to ridicule and disdain it? This is a poignant dilemma for the country music scholar and is becoming a topic of discussion among sociologists, anthropologists, museum curators, and social critics.”

Anyways, to move past this thoughtful navel-gazing, I want to get into a dimension of 1Q84 that I found extremely interesting. Probably my favourite part is Chapter 10 of Book 1 (A Real Revolution with Real Bloodshed), where Tengo talks to Fuka-Eri’s current guardian, a former anthropology professor and friend of Fuka-Eri’s father. Fuka-Eri’s father (Tamotsu Fukada) was an academic and Maoist revolutionary, enthusiastic about the Cultural Revolution, who gathered a number of students to start a commune in the mountains of Takao. There is a fascinating section on the splintering of the commune into a moderate faction and a more radical one:

“Under Fukada’s leadership, the operation of Sakigake farm remained on track, but eventually the commune split into two distinct factions. Such a split was inevitable as long as they kept Fukada’s flexible unit system. On one side was a militant faction, a revolutionary group based on the Red Guard unit that Fukada had originally organized. For them, the farming commune was strictly preparatory for the revolution. Farming was just a cover for them until the time came for them to take up arms. That was their unshakable stance.”

This paragraph reminds me of the case of the Tarnac Nine. It is within the realm of possibility Murakami had heard about this case, because their arrest was in 2008, shortly before 1Q84’s first books were published. There’s a commune in Tarnac that was involved in the operation of a nearby general store (Magasin General, Tarnac). Giorgio Agamben wrote a brief post on this affair describing it this way:

“On the morning of November 11, 150 police officers, most of which belonged to the anti-terrorist brigades, surrounded a village of 350 inhabitants on the Millevaches plateau, before raiding a farm in order to arrest nine young people (who ran the local grocery store and tried to revive the cultural life of the village). Four days later, these nine people were sent before an anti-terrorist judge and “accused of criminal association with terrorist intentions.””

The social theorist Alberto Toscano described the event in similar terms:

“On 11 November 2008, twenty French youths are arrested simultaneously in Paris, Rouen, and in the small village of Tarnac (located in the district of Corrèze, in France’s relatively impoverished Massif Central region). The Tarnac operation involves helicopters, one hundred and fifty balaclava-clad anti-terrorist policemen and studiously prearranged media coverage. The youths are accused of having participated in a number of sabotage attacks against the high-speed TGV train routes, involving the obstruction of the train’s power cables with horseshoe-shaped iron bars, causing material damage and a series of delays affecting some 160 trains. Eleven of the suspects are promptly freed. Those who remain in custody are soon termed the ‘Tarnac Nine’, after the village where a number of them had purchased a small farmhouse, reorganised the local grocery store as a cooperative, and taken up a number of civic activities from the running of a film club to the delivery of food to the elderly. In their parents’ words, ‘they planted carrots without bosses or leaders. They think that life, intelligence and decisions are more joyous when they are collective’.”

The Professor’s farming of Akebono (the radical offshoot of Sakigake) are framed in similar terms to the way anti-terrorist police in France portrayed the activities of the Tarnac co-op farm, as a front for revolutionary activity. Of course, if you read the Invisible Committee’s “Coming Insurrection”, allusions to such notions are elaborated on:

“Every commune seeks to be its own base. It seeks to dissolve the question of needs. It seeks to break all economic dependency and all political subjugation; it degenerates into a milieu the moment it loses contact with the truths on which it is founded. There are all kinds of communes that wait neither for the numbers nor the means to get organized, and even less for the “right moment” — which never arrives.”

But this excerpt follows a notion of the commune that is not so easily type-casted into the rural commune of Tarnac:

“Communes come into being when people find each other, get on with each other, and decide on a common path. The commune is perhaps what gets decided at the very moment when we would normally part ways. It’s the joy of an encounter that survives its expected end. It’s what makes us say “we,” and makes that an event. What’s strange isn’t that people who are attuned to each other form communes, but that they remain separated. Why shouldn’t communes proliferate everywhere? In every factory, every street, every village, every school. At long last, the reign of the base committees! Communes that accept being what they are, where they are. And if possible, a multiplicity of communes that will displace the institutions of society: family, school, union, sports club, etc. Communes that aren’t afraid, beyond their specifically political activities, to organize themselves for the material and moral survival of each of their members and of all those around them who remain adrift. Communes that would not define themselves — as collectives tend to do — by what’s inside and what’s outside them, but by the density of the ties at their core. Not by their membership, but by the spirit that animates them.”

There is a strong eschatological element in the writings of the Invisible Committee, that some radical political theologians have picked up on (e.g. see Ward Blanton’s lecture on the Invisible Committee ). Because of Julien Coupat’s arrest as one of the Tarnac Nine, the Invisible Committee has become associated with the journal Tiqqun. In “Theory of Bloom” Tiqqun is defined:

“The French rendering of the Hebrew word Tikkun, meaning to “perfect”, “repair”, “heal”, or “transform”. In rabbanical school, students study mystical texts that view tikkun as the process of restoring a complex divine unity. A tikkun kor’im (readers’ tikkun) is a study guide used when preparing to chant the Torah, or to read from the Torah in a Jewish synagogue. People who chant from the Torah must differs from that written (the Kethib) in the scroll.”

The Wikipedia article for Tiqqun says the word is derived from the “Hebrew term Tikkun olam, a concept issuing from Judaism, often used in the kabbalistic and messianic traditions.”

Murakami certainly alludes to this intersection of eschatology, theology, and politics, firstly in his narrative mechanism which has this Maoist commune turn into a secretive religious cult. He ties the religious and political in this way, but in a manner that I myself find unconvincing. Many of these co-operative farms are anti-hierarchical and I find it difficult to see, even for a commune of the authoritarian left to turn into something resembling Sakigake in the novel. Regardless, I think the intersection of radical religion and politics in 1Q84 to be a fascinating subject to explore, even if I found Murakami’s particular approach unsatisfying. There is of course an eschatological dimension that Murakami gestures towards in various chapters, often in amusing an humorous ways. One of my favourites is in the following chapter (Chapter 11):

As a woman, Aomame had no concrete idea how much it hurt to suffer a hard kick in the balls… “It hurts so much you think the end of the world is coming right now. I don’t know how else to put it. It’s different from ordinary pain,” said a man, after careful consideration, when Aomame asked him to explain it to her.

Aomame gave some thought to his analogy. The end of the world?

“Conversely, then,” she said, “would you say that when the end of the world is coming right now, it feels like a hard kick in the balls?”

Aomame was called in and instructed to rein in the ball-kicking practice. “Realistically speaking, though,” she protested, “it’s impossible for women to protect themselves against men without resorting to a kick in the testicles. Most men are bigger and stronger than women. A swift testicle attack is a woman’s only chance. Mao Zedong said it best. You find your opponent’s weak point and make the first move with a concentrated attack. It’s the only chance a guerrilla force has of defeating a regular army.”

The manager did not take well to her passionate defense. “…I don’t care what Mao Zedong said—or Genghis Khan, for that matter: a spectacle like that is going to make most men feel anxious and annoyed and upset.”

If there’s any guy crazy enough to attack me, I’m going to show him the end of the world—close up. I’m going to let him see the kingdom come with his own eyes.”

The Witnesses’ rendition of the Lord’s prayer is recurring theme that surfaces throughout the novel, and even if it is presented in a cynical manner by Murakami, I think it still evokes a particular mode of contemplation that I found interesting. The Jehovah’s Witnesses are the obvious allusion Murakami is making and their pacifism is even explicitly mentioned by Ushikawa: “They are well known to be pacifists, following the principle of nonresistance.”

Pacifism, of course, more associated with the radical Christians of the anabaptist tradition, although I have yet to encounter the connection between Jehovah’s Witnesses and Anabaptism, other than certain millenarian impulses they might share. Anyways, I think this an interesting node that Murakami marks, posing the question of violence and justice: revolutionary violence (of Akebono), assassination (Aomame’s side gig), and sexual violence (experienced by the women that the dowager tries to protect). What causes aversion to political and religious radicals, fundamentalists, etc?

Murakami’s answer is coercion and the denigration of the individual. This is epitomized in a dialogue Aomame has with the dowager, where the dowager asks:

“Are you a feminist, or a lesbian?” Aomame blushed slightly and shook her head. “I don’t think so. My thoughts on such matters are strictly my own. I’m not a doctrinaire feminist, and I’m not a lesbian.”

“That’s good,” the dowager said. As if relieved, she elegantly lifted a forkful of broccoli to her mouth, elegantly chewed it, and took one small sip of wine.

This is very similar to the sort of ideology that Jordan Petersen subscribes to. It is a ‘higher than thou’ purity politics that looks down on any sort of collective organization that betrays any sort of hypocrisy. Yet most religious traditions recognize that any sort of collective organizing is bound to live in contradiction with its ideals. Within the Christian tradition, thoughtful adherents recognize the Church as a ‘fallen’ institution composed of ‘sinners’. I think it is important to recognize and confess the short fallings of previous attempts to realize ideals while not abandoning the ideals because people that came before us have severely fucked it up. Another world is possible, and I think if we fall back into our silos of individualism we will not realize this other world. Murakami provides an almost Kierkegaardian framing of what is essentially ritual rape in the novel — and I found that disturbing, though in the realm of magical realism, I’m not qualified to make any meaningful commentary. What I will confess is that my own life betrays a certain sort of ‘bourgeois individualism’ but I have not yet reached a form of cynicism that celebrates it, and I hope I won’t anytime soon.

Anyhow, beyond these critiques, I enjoyed this novel a lot, and I think it brought up interesting questions to contemplate. I found the Proust jokes hilarious, some of the funniest moments in the book. Curiously, I have never finished reading Orwell’s 1984. I was supposed to have finished reading it for a Grade 12 literature class, but I recall that period of the semester as a tremendously busy one for me. I do intend to finish it one day soon, and Orwell’s democratic socialism is a fascinating lens through which to also examine many of the themes that Murakami explores, including those of agency and freedom. There are these strange lines in the book that I don’t quite know what to make of:

“He leaned against the wall, in the shadows of the telephone pole and a sign advertising the Japanese Communist Party, and kept a sharp watch over the front door of Mugiatama.“

There are funnier allusions to this like:

“Have you heard about the final tests given to candidates to become interrogators for Stalin’s secret police?” “No, I haven’t.”

“A candidate would be put in a square room. The only thing in the room is an ordinary small wooden chair. And the interrogator’s boss gives him an order. He says, ‘Get this chair to confess and write up a report on it. Until you do this, you can’t leave this room.’ ”

“Sounds pretty surreal.”

“No, it isn’t. It’s not surreal at all. It’s a real story. Stalin actually did create that kind of paranoia, and some ten million people died on his watch—most of them his fellow countrymen. And we actually live in that kind of world. Don’t ever forget that.”

...“So what kind of confession did the interrogator candidates extract from the chairs?”

“That is a question definitely worth considering,” Tamaru said. “Sort of like a Zen koan.”

“Stalinist Zen,” Aomame said.

I have my own views on Murakami’s crypto-Calvinist sections, which is not unrelated to Murakami’s interwoven narrative technique, and in excerpts such as the one I opened with about the etymology of ‘lunatic’. Also, I actually quite enjoyed the way Murakami alluded to Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor passage from the Brothers Karamazov — where Satan frames miracles as a sort of spectacle when trying to tempt Christ in the wilderness. I’ve always thought that there’s certainly some Debordian comment that can be made with respect to that. In fact, the notion of spectacle, and this process of reducing agency such that we become mere spectators, is itself thematic in Murakami’s fiction, especially here. Again, it is this crypto-Calvinist notion of fate, that one’s future is already predetermined and no matter what one might try, it is inevitable. (This must be related to Murakami’s quoting of Carl Jung: “Called or not called, God is there”.) And so one becomes almost a spectator to one’s own life unfolding under the predetermined path of capital. Yet curiously, Tengo and Aomame do escape from Leader’s prophetic claim that was to befall Aomame, out from 1Q84, back up the stairwell back to the path of 1984. If only escaping from “late declining capitalism” (Murakami’s term) was that simple.

Though I had many reservations, 1Q84 was breezy read and I think that’s a testament to how fun Murakami’s writing can be, and this was one of those books where this was very much the case.

0 notes