#zendegi va digar hich (1992)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Immaginare la Vita

— Dario CECCHI

Immaginare la vita: questo potrebbe essere preso come il programma implicito di tutta la filmografia di Kiarostami. Ci sono i cortometraggi patrocinati dal Kanun, che mettono al centro luoghi (la campagna in trasformazione, la periferia povera di una capitale in rapida espansione) e persone (i bambini, i vecchi, le donne): questi soggetti chiedono che le loro vite non siano solo documentate, ma anche in una certa misura narrate a causa della loro marginalità. Ci sono poi i film, come nel caso della trilogia di Koker o di Ta'm e guilass (1997; Il sapore della ciliegia), in cui a essere raccontato non è nemmeno una storia in quanto tale, quanto l'incontro tra il cinema e una vicenda umana: qui il film non testimonia tanto una vita, quanto l'incontro tra il cinema e la vita. Si vede bene, allora, che l'apporto immaginativo si fa più forte, perché ciò che è chiamato vita non si fa più comprendere solo come quella vita. La vita, così come emerge dai film di Kiarostami, è riferita allo stesso tempo alla singola vicenda individuale e a tutto quello che si affaccia oltre ciò che della vita le immagini lasciano vedere e che tuttavia il film lascia immaginare. È solo il cinema - grazie a un montaggio usato spesso per far letteralmente sentire la presenza del fuori campo nell'immagine, come nel finale di Nema-ye Nazdik (1990; Close-Up), di Zendegi va digar hich (1992; E la vita continua), o del Sapore della ciliegia - a poter mettere in comunicazione una vita con tutto ciò che nel mondo le darà occasione di proseguire, in breve con la vita.

Immaginare la vita non significa, di conseguenza, fantasticare un'altra vita. Immaginazione e vita designano due cose affatto differenti da fantasia e realtà. La fantasia è il potere di "fingersi" una realtà diversa da quella che è offerta dai puri dati di fatto. All'immaginazione non manca la capacità di attivare una modalità di pensare le cose altrimenti da come sono, o meglio da come appaiono immediatamente. Non si tratta però di essere trasportati in un "altro mondo": questo pensare altrimenti non si applica a mondi possibili, ma alle forme di questo mondo. Dico le forme perché, se il cinema di Kiarostami esercita un potere sulle cose, è proprio quello di far emergere le loro forme. E per forma si può intendere niente altro che questo: i punti di apertura nelle cose, in cui queste lasciano intravedere dove si dirigono, dove porteranno la vita. Così nel finale di Zire darakhatan zeyton (1994; Sotto gli ulivi) possiamo chiederci dove l'amore, una delle forme più potenti che la vita può assumere, condurrà le esistenze di Hossein e Tahereh e fino a che punto lo sguardo del cinema potrà accompagnare i due (possibili) amanti. Le forme stanno perciò tra i dati di fatto attuali e visibili e quelli futuri e possibili. È dandole forma attraverso le immagini che il cinema può testimoniare la vita. Dall'ottica di Kiarostami, in fondo, la vita non si trova - o non si trova eminentemente - che nell'intervallo tra le immagini; e con essa in questo "*tra" si trovano anchel cinema e l'immaginazione.

In questo senso si possono intendere le parole pronunciate da Kiarostami durante un'intervista: «quando la poesia raggiunge il massimo, e quindi ottiene un potere, in quel momento inizia la sua menzogna»[1]. Il regista riporta qui un pensiero del poeta e filosofo persiano Nezami, che considera, in linea con la tradizione del suo Paese, un maestro di saggezza. Questo concetto va però ricondotto a un preciso contesto culturale - Nezami appartiene al periodo "classico" della letteratura persiana, essendo vissuto tra il xu e il xI secolo - e a un genere artistico ben definito, la poesia; altrimenti si sarebbe indotti a opporre la realtà (vera) all'opera (bella, ma menzognera) dell'arte e si sarebbe così portati a interpretare quello di Kiarostami come un cinema "di fantasia". Nel confronto con la poesia il cinema sconta un "di meno", ma mostra anche un "di più". Il cinema è meno della poesia, perché solo attraverso le immagini della poesia, che sono fatte di parole, è possibile confrontare il lavoro dell'immaginazione con il linguaggio attraverso cui normalmente esprimiamo i nostri pensieri e ci riferiamo a stati di cose. È a proposito della poesia che si può stabilire in senso stretto una distinzione tra verità e menzogna. Il cinema è però in vantaggio sulla poesia, perché le sue immagini visive, il cui senso dipende dal montaggio e non dal linguaggio, permettono di riferirsi alle cose sospendendo momentaneamente la questione della verità o della menzogna della realtà narrata. Il cinema induce anzi lo spettatore a esplorare fino a che punto la realtà è tale nella misura in cui sono gli uomini a immaginarla, cioè a darle forma.

Non è un caso se, nel film in cui omaggia il "maestro" Nezami, Shirin (2008; Id.), le parole del poeta, messe in scena in forma teatrale, diventano un fuori campo - lo spettatore ascolta, ma non vede l'azione sulla scena che attraverso le battute recitate dagli interpreti -, mentre la macchina da presa si concentra sulle spettatrici presenti a teatro, sui loro volti attoniti, attenti, rapiti, commossi dalla storia. Il film non indaga la "menzogna" poetica del racconto mitico della principessa che l'amore porterà all'amarezza e al dolore, ma si interessa alla realtà viva e mobile delle emozioni delle donne che seguono la vicenda. Si può allora ben dire - e capire in che senso - il cinema di Kiarostami è un cinema in cui l'immaginazione è forza della vita. Non è casuale se il cinema del regista iraniano abbia fatto spesso riferimento - nei suoi esiti migliori - proprio al suo Paese: se il suo compito è indagare la vita attraverso l'immaginazione, è naturale che abbia cominciato "guardandosi intorno", cercando proprio nelle immagini più usuali, più immediate e reali il "sostrato immaginativo" presente nella vita.

Vorrei in primo luogo esprimere la mia gratitudine al mio maestro, Pietro Montani, per avermi insegnato quanto si può apprendere dal cinema. Ringrazio gli amici Luca Venzi, per la possibilità offertami, Alessia Cervini e Alessio Scarlato, per i consigli e il sostegno. Vorrei inoltre ricordare la mia famiglia per avermi trasmesso una certa "sensibilità persiana". Un grazie sentito va a Chiara Supplizi: nomen omen ma in senso contrario e uno (di lungo corso) va anche a Catia della Libreria Fahrenheit e al suo harem. Vorrei ringraziare infine, last but not least, Edda Marazia, che ha a cuore la mia creatività.

[1] J-L. Nancy, L'évidence du film. Abbas Kiarostami, Yves Gevaert, Bruxelles, 2001; tr. it. a cura di Alfonso Cariolato, Abbas Kiarostami. L'evidenza del film, Donzelli, Roma 2004, p. 120.

Works Cited:

Cecci, D. (2013). Abbas Kiarostami: Immaginare la vità. Roma, Lazio, Italia: Edizione Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo.

0 notes

Photo

“Everyone has their own problems.”

And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#long#shot#Life and Nothing More…#Life and Nothing More#nature#back#1992#earthquake#iran#quote#cars#childhood#Zendegi va digar hich#Farhad Kheradmand#Buba Bayour#Hocine Rifahi#trees

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

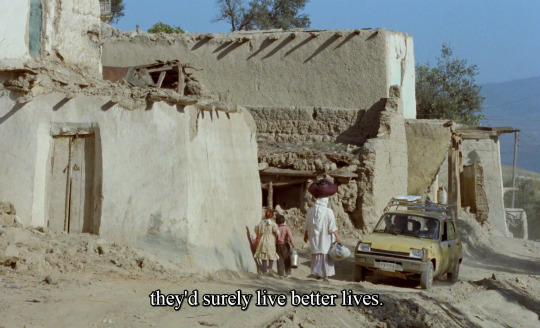

Life, and Nothing More... (Persian: زندگی و دیگر هیچ Zendegi va digar hich)

[Abbas Kiarostami - 1992]

#Life and Nothing More...#1992#Kiarostami#Abbas Kiarostami#Zendegi va digar hich#زندگی و دیگر هیچ#Persian movie#Persian cinema#iran#Iranian cinema#Iranian cinema#Iranian movies#life#art#1990s#90s

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ne zaman bu üçlü ağaç sahnelerini görsem, Kiarostami'nin "İşin kaçta kaçını estetik, kaçta kaçını konsept oluşturur emin değilim. Ama elbette ki yalnız bir ağaç, birkaç tane ağaçtan daha ağaçtır. " cümleleri aklıma geliyor...

🎬 Jungfrukällan, Ingmar Bergman, 1960.

🎬 Offret, Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986.

🎬 Zendegi va digar hich, Abbas Kiarostami, 1992.

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite movies I’ve seen this year (june 1 - december 31)

1.Moartea domnului Lãzãrescu (2005) - Dir. Cristi Puiu 2.Politist, adjectiv (2009) - Dir. Corneliu Porumboiu 3.Zendegi va digar hich (1992) - Dir. Abbas Kiarostami 4.Marseille (2004) - Dir. Angela Schanelec 5.Roman Holiday (1953) - Dir. William Wyler 6.Vive L'Amour (1994) - Dir. Tasi Ming-Liang 7.Die Antigone des Sophokles nach der Hölderlinschen Übertragung für die Bühne bearbeitet von Brecht 1948 (Suhrkamp Verlag) (1992) - Dir. Jean-Marie Straub, Danielle Huillet 8.Maborosi (1995) - Dir. Hirokazu Koreeda 9.Dobro pozhalovat, ili Postoronnim vkhod vospreshchen (1964) Dir. Elem Klimov 10.Las vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953) - Dir. Jacques Tati

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

kelimeler, mazlumların yaralarını serinleten merhemlere benzer..

Ercan Kesal, Velhasıl s.38 Fotoğraf: Abbas Kiarostami’nin 1992 yapımı, “Zendegi va digar hich” (Ve Yaşam Sürüyor) filminden.

#zendegi va digar hich#ercan kes#velhası#abbas kiarostami#abbas kiyarüstemi#and life goes on#life and nothing more#زندگی و دیگر هیچ#farhad kheradmand

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Zendegi va digar hich / Life, And Nothing More ... (1992), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zendegi va digar hich (1992)

0 notes

Text

La trilogía de Koker: el desmontaje de la realidad en el cine de Abbas Kiarostami

Ahmed, el pequeño héroe de "¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?" (1987)

Nico Nicolli Domingo, 5 de diciembre de 2021 10:00 hs

El director iraní ganó fama en Occidente a partir de estas historias entrelazadas en la aldea remota de Koker, como parte de un ejercicio de metacine que reconfigura los límites entre la ficción y el documental.

Limitarlo a director, guionista y fotógrafo sería injusto. Abbas Kiarostami fue un poeta del cine. Cuando partió en 2016, se perdió para siempre un alquimista de la aventura, que creaba mundos entre la ficción y el documental y demostraba las posibilidades en el universo infinito de lo cotidiano. Un autor genuino, calmo y sensible, en cuyas historias universales se encuentra el potencial del poderío humano.

La trilogía de Koker (1987-1994), como popularmente se la conoce pese al desacuerdo de su hacedor, lanzó a Kiarostami a la vanguardia de la escena mundial. Más allá de algunos rostros familiares, las tres películas apenas comparten el escenario de Koker, una aldea rural iraní en medio de la nada, mientras su estructura narrativa va in crescendo en cada entrega hasta controlar las reglas -¿las hay?- del metacine. El director dialoga constantemente sobre su propia obra sin pecar de narcisista: presenta un discurso reflexivo sobre su propia construcción relatora.

Kiarostami había trabajado desde los años 70 las problemáticas de la infancia en su rol de realizador cinematográfico en el Instituto para el Desarrollo Intelectual de Niños y Jóvenes Adultos de Teherán. Su primer corto “El pan y la calle” (The Bread and Alley o Nān o Kūcheh, 1970) y largometrajes iniciales como “La experiencia” (The Experience o Tadjrebeh, 1973) y “El pasajero” (The Traveler o Mossafer, 1974) examinaron el comportamiento humano y convirtieron lo que parece superfluo (un perro peligroso, el amor adolescente, un partido de fútbol) en un manifiesto de las nuevas generaciones frente al juicio inquisidor de los adultos.

"¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?" (1987) de Abbas Kiarostami

Años más tarde, la búsqueda de Kiarostami se corrió de lo pedagógico y viró a la rebeldía pura en “¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?” (Where Is the Friend’s Home? o Khane-ye doust kodjast, 1987), la primera pieza en la trilogía de Koker. Aquí, el realizador reivindica que aquella inocencia de la niñez funciona como el dispositivo de ruptura contra la disciplina persa, encarnada en los mayores.

Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor) es un nene de ocho años urgido por devolverle a su amigo el cuaderno de las tareas que se llevó por error. De no dárselo antes de la clase, su compañero de banco quedará expulsado de la escuela. Nuestro pequeño héroe es incomprendido por su mamá, su abuelo y cada adulto que se cruza en el camino, por lo que su viaje -de manual, simple y tradicional, al estilo que acostumbra Kiarostami- con destino al pueblito Poshteh pone a prueba sus propias ideas sobre la vida.

La mayoría de las tomas se establecen desde los ojos del protagonista, que reflejan la valentía y la sensibilidad, mientras los adultos terminan a veces recortados, alejados y/o marginados en el encuadre. La comunidad de Koker y alrededores es apática por naturaleza. Sin embargo, el director evita la condena; más bien, desarrolla la conciencia moral de una cultura arrastrada por siglos, por ejemplo, con un abuelo que exterioriza los castigos recibidos para su disciplinamiento o una madre que queda atrapada entre las tareas domésticas.

La recompensa de Ahmed en "¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?" (1987)

Es célebre la postal del camino zigzagueante que recorre Ahmed en busca de su compañero de clase, que muta a un terreno desgarrado en “Y la vida continúa” (And Life Goes On o Zendegi va digar hich, 1992), segunda parte del tríptico y filmada en el Koker arrasado tras el terremoto de Manjil-Rudbar en 1990.

Los caminos en la trilogía de Koker (Abbas Kiarostami, 1987-1994)

Esta vez, la cámara de Kiarostami abandona el ritmo de la carrera del niño. Entre planos piadosos y travellings a bordo de un auto destartalado, “Y la vida continúa” es una road movie capaz de rescatar la belleza aun en los eventos más devastadores, a través del viaje de un director (Farhad Kheradmand, alter egode Kiarostami) y su hijo Pouya (Buba Bayour) en busca de los chicos que aparecieron en “¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?”.

"Y la vida continúa" (1992) presenta un alter ego de Abbas Kiarostami, en busca de los actores de la primera película

El cineasta iraní revierte el planteo clásico de la imagen simbólica que va de lo particular a lo universal. Mientras en el primer filme invitaba a compartir la urgencia de un acto relativamente trivial (la devolución del cuaderno) para expandirse a la cultura de todo un pueblo, en la secuela parte desde una tragedia colosal para focalizarse en los testimonios pequeños, tapados por el adobe deshecho, las colinas repobladas y los bosques simuladores del hogar perdido.

La del director y su hijo es una peregrinación culposa en busca de esperanza. El altruismo que encarnaba Ahmed ha desaparecido; incluso, pese a ser el disparador inicial, a él nunca lo vemos en el metraje. Solo quedan caras extraviadas frente al fantasma de la muerte, al que Kiarostami decidirá enfrentarse de lleno en “El sabor de las cerezas” (Taste of Cherry o Ta’m-e gilâs, 1997). No es casualidad que el cineasta prefiriera la inclusión de esta película en su tríptico cinematográfico.

"Y la vida continúa" (1992) de Abbas Kiarostami

Si en “¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?” la ficción se imponía a la realidad, en “Y la vida continúa” el trucaje queda expuesto deliberadamente, ya sea en su base narrativa alineada a los parámetros de André Bazin o en los guiños/easter eggs en pantalla. Lo observamos en el afiche del filme que hizo famosa a la aldea, en la celebración de la Copa del Mundo (nada menos que Argentina-Brasil) o en el anciano que señala a su “casa para el cine” porque la verdadera está hecha polvo.

No obstante, es “A través de los olivos” (Through the Olive Trees o Zīr-e Derakhtān-e Zeytūn, 1994) la película de Kiarostami que logra reconocerse a sí misma como película. Como si fuera una superación del juego tras bambalinas de François Truffaut en “La noche americana” (La nuit américaine, 1973), recuperamos al joven/actor (Hossein Rezai) que le propuso matrimonio a su novia en una escena de “Y la vida continúa” desde la óptica de una tercera manifestación del director, en la piel de Mohamad Ali Keshavarz.

"A través de los olivos" (1994) de Abbas Kiarostami

Ya emancipado de lo formal, Kiarostami ajusta la narrativa con secuencias aisladas entre sí, pero unidas mediante su característica poesía. Apenas en segundos se explica el enigma de Ahmed, sin que afecte al director en su decisión de avanzar sobre sus inquietudes como el amor no correspondido y el clasismo. Al respecto, el propio Hossein propone en un momento que “si la gente leída se casara con los analfabetos y los que no tienen casa con los terratenientes, todos podríamos ayudarnos”.

"A través de los olivos" (1994) de Abbas Kiarostami

Las películas de la trilogía de Koker comparten un patrón de defensa del -castigado- don de la humanidad. En el final de “¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?”, Ahmed descubre una flor en su cuaderno que agasaja su altruismo; en “Y la vida continúa”, el director y Pouya son auxiliados por un lugareño para retomar su andanza más allá del zigzag; y en “A través de los olivos”, Hossein abandona su caminar pausado y cruza el prado detrás de su amada. La esperanza, el germen del movimiento.

Abbas Kiarostami era un firme creyente de un cine que brinde más posibilidades, experimentación y tiempo. Hablaba de uno a medio fabricar, como plasmó en su trilogía al desmontar la realidad. De patrones formales, pero inacabado. Solo es posible completarlo con el espíritu creativo de los espectadores.

”¿Dónde está la casa de mi amigo?” y “A través de los olivos” están disponibles para ver en la plataforma MUBI.

0 notes

Photo

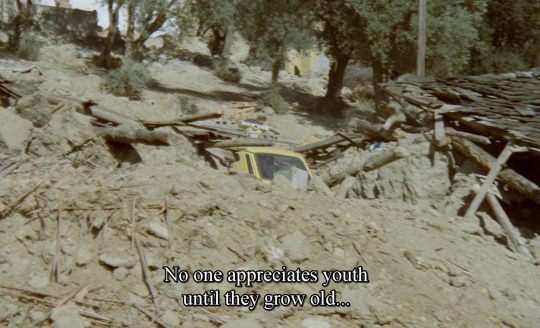

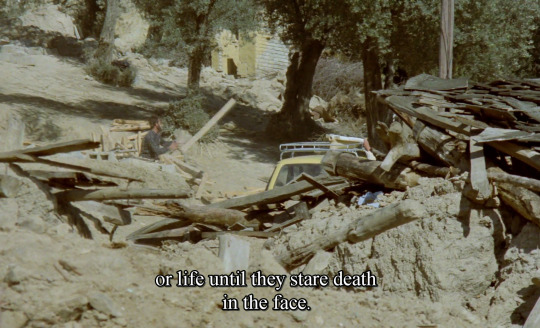

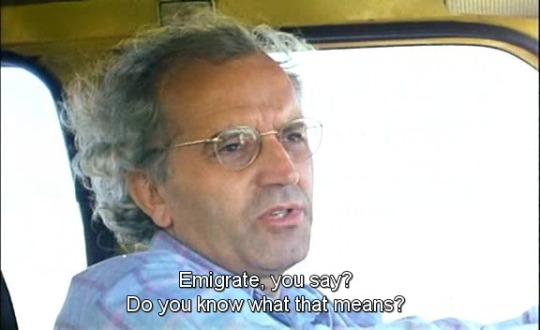

And Life Goes On… (Abbas Kiarostami, 1992)

#And Life Goes On…#And Life Goes On#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#quote#death#elderly#youth#life#philosophy#Life and Nothing More…#Life and Nothing More#1992#face#Zendegi va digar hich

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

111. Trilogia Koker: E a Vida Continua (Zendegi va digar hich, 1992), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

#cinema#abbas kiarostami#farhad kheradmand#buba bayour#Iranian cinema#1990s movies#classic movies#koker trilogy#drama#father son relationship#class differences#disaster#earthquake#sequence#non professional actor#road movie#film director#world cinema#cinefilos

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Life, and Nothing More... (Persian: زندگی و دیگر هیچ Zendegi va digar hich)

[Abbas Kiarostami - 1992]

#Abbas Kiarostami#Kiarostami#Zendegi va digar hich#Life and Nothing More...#زندگی و دیگر هیچ#Persian movie#Persian movies#iran#Iranian cinema#Iranian cinema#Iranian movies#emigrate#earthquake#earthquakes#1990s#90s#life#freedom#humans#Koker trilogy#Koker#Docufiction

396 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry and the Peculiar Alliance of Film and Life

The surprising, out of the blue ending of Abbas Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or winning masterpiece, Taste of Cherry (1997, Ta’m e guilass) might catch the spectator off guard, or even startle them, as it seems very contradictory, almost an inconsistent flaw, in the whole of the film. Such an evaluation caused by a moment of aesthetic confusion is only seemingly valid, however. To anyone familiar with Kiarostami’s work, the ending is anything but contradictory to the logic of his cinematic poetry. During his impressive career, Kiarostami excelled in crafting an original cinema that was always questioning itself as it questioned life. While his camera perceives, records, and articulates, it also structures and constitutes, which is something Kiarostami’s cinema meticulously reflects on in a self-reflective or meta-fictive fashion. If the protagonist of Taste of Cherry contemplates suicide because of the meaninglessness of his life -- the lack of reason why he was brought on earth without anyone consulting his opinion about it --, it is surprisingly natural for Kiarostami’s cinema to do the same; that is to say, to ask the question ��why cinema?” which also inevitably entails the question “what is cinema?”. In this essay these questions shall not be answered but only raised again and again, while trying to grasp a wonderful film like Taste of Cherry.

Taste of Cherry begins with a middle-aged man driving around Tehran, offering to give passersby a ride to their destination. To each of the three people who take his offer, he proposes to give a large amount of cash in exchange for a peculiar service. He asks them to aid him in committing suicide. The aid required for this act of self-annihilation means shoveling soil on his body after he has taken an overdose of sleeping pills. He has already chosen the place for his burial: a pit under a lone cherry tree at an excavation site in the outskirts of Tehran where a lot of construction is going on. The first passenger, a young Kurd soldier, is shocked by this proposal to the point that he runs away in horror. The second passenger, an Afghan student visiting Tehran for a seminar tries to reason with the man, but since he declines to help the man, their paths go different ways. The third passenger, an aging professor, who has personal experience with suicidal thoughts, tries to comfort the man and assure him of the good things in life. Disappointed by the man’s disinterestedness in changing his mind, the professor still agrees to help the man in order to finance the medical operations his ailing daughter desperately needs. As the night falls, the man lays down on his open grave to gaze at the pale Moon peeking behind clouds in the sky. In terms of telling a story, Taste of Cherry has an open ending, which leaves the fate of the protagonist open for interpretation, as Kiarostami famously cuts from this last moment to behind-the-scenes footage of him and his crew making the film.

Not far from the three previous films Kiarostami had made earlier in the 1990′s, Close-Up (1990, Nema-ye Nazdik), Life, and Nothing More... (1992, Zendegi va digar hich), and Through the Olive Trees (1994, Zire darakhatan zeyton), Taste of Cherry lies securely on familiar ground in Kiarostami’s cinema which is often meta-fictive by nature. The word “securely” should be juxtaposed with its negation, too, however, since it is precisely by questioning itself that Kiarostami’s cinema finds a unique poetics between confidence in itself and the readiness to suspect what it affirms and articulates. Due to its structure, Taste of Cherry discloses its poetic alliance to the three films mentioned above only towards its very end, but in order to understand this alliance, one must grasp what the film is about.

Typically for Kiarostami, Taste of Cherry begins without giving the spectator background knowledge of where the protagonist is coming from and what is he thinking, nor does it really ever explain why is he contemplating the dead-serious questions that he does. The narrative tendency to throw the spectator into the fictive world of the film without giving these clear frames of reference reflects Kiarostami’s “neorealist” ideals of chance, continuity, and authenticity which manifest themselves more strongly on the level of style (the use of on-location shooting and the long take, for example). Such narrative gives the spectator slowly information about the protagonist. His suicidal plans are disclosed to the spectator only when they are revealed to the first passenger, the young Kurd soldier. In this way, narrative does not really focalize into the protagonist’s point of view which, once again, reflects Kiarostami’s “neorealist” ideals of anti-psychologizing story telling. It also, however, resonates with the protagonist’s subjective experience regarding the fact that first person access about one’s own experiences is insurmountable, meaning that another person can never access the thoughts and feelings of someone else. The protagonist explains to the second passenger that others could not understand his intentions even if he tried to shed light on them because others “could not feel what I feel”. In turn, the third passenger claims that matters look worse than they are to the protagonist merely due to his subjective point of view, but the banal alternatives the third passenger offers to the protagonist receive no response in the protagonist’s more or less blank stare. In other words, Kiarostami’s narrative, which refuses to focalize, reflects the protagonist’s experience of the phenomenological notion of the primacy of first person access as it, so to speak, respects his privacy without trying to uncover the innermost of his self-hood.

Nonetheless, it would still strike one as odd to characterize Kiarostami’s narrative in Taste of Cherry as “purely objective” or “purely mimetic” (in the sense that mimetic narrative refers to third person narrative which merely recounts what happens without drawing attention to the fact that it is being narrated: the most classical cinematic narrative, that is). The reason for this oddness is that there are shots in Taste of Cherry which could be categorized as point of view shots, indicating internal focalization. For example, there are reverse shots of the passengers in the car, working as counterpoints to the reverse shots of the protagonist, there is a shot of a truck dropping gravel down a hill which the protagonist observes from the nearby watchtower, there is a shot of boulders dropping irregularly down to a machine as the protagonist casts his shadow on them, there are landscape shots of the hills, there are shots of marching soldiers in the distance, and shots of children playing football accompanied with medium close-ups of the protagonist looking to their direction. Then there is, of course, the long shot of the moon being concealed by vague clouds in the night as the protagonist lies in his open grave.

These could be seen as point of view shots, which one might further characterize as examples of internal focalization (without, however, the deepest form of such focalization, that is, the use of voice-over), but I would beg to differ. In Kiarostami’s “neorealist” or phenomenological aesthetics they are rather a cinematic variation of free indirect discourse, a form of narrative that locates between mimetic (the act of narrative is transparent and the fictive events are “directly” shown) and diegetic narrative (the act of narrative is highlighted as the fictive events are “indirectly” told). Free indirect discourse in the cinema could be a shot which both is and is not a point of view shot. This seeming paradox seems to strike true notes in Kiarostami’s cinema -- as well as many others who excelled in postwar cinema (Antonioni, above all).

Kiarostami’s use of cinematic free indirect discourse is most evident, I believe, in the scene where the protagonist climbs up to a “watchtower” of a lone guardian at the excavation. There is a brief moment where the protagonist looks at gravel falling down a hill. First, there is a low-angle shot from the protagonist’s direction where a truck drops gravel on the edge of a hill and exits the screen space. Second, there is a long medium shot where the camera is situated inside the watchtower, showing the protagonist behind a window, outside on the exterior of the watchtower, reflections from the off-screen space on that window, and the gravel on an even deeper plane. The first shot is -- or so it seems at least -- a point of view shot from the protagonist’s perspective, but at the same time Kiarostami’s narrative does not seem to show the gravel as anything peculiar or filtered through subjectivity. To be overly blunt about this, there is nothing surreal in the falling down of the gravel. In the sense of free indirect discourse, narrative shows the things themselves (the falling gravel) through the protagonist without focalizing into his subjective point of view.

In literature, an alternative technique could be for a third person narrator to first tell that “person A thought about X” and then to shift into a perspective in between of third and first person where a line, a single line perhaps, would make a claim about X, for example, “X was beautiful” without narrative adding the conventional “said A” or “thought A,” to close the sentence. The reasons to do this are plentiful, of course. In most cases, however, it seems to be used to articulate an interface between consciousness and reality or their mutual entanglement (think of the wonderful novels of Virginia Woolf, for one). It is almost as if Kiarostami’s narrative was affirming that there is no way to know what a person is thinking because of the primacy of first person access even for narrative, but narrative can show something through someone without reducing the “what” into the “how”. Narrative can, in other words, embrace this interrelation between consciousness and reality without, however, identifying the one with the other in any absolute sense.

But what do these shots of gravel, dirt, and soil mean? Most of Taste of Cherry takes place at the excavation in the outskirts of Tehran, maybe a construction site, where people work with gravel, other people collect items, soldiers march, and children play at. Gravel, boulders, sand, and soil are central elements in the film. The presence of construction taking place might be seen as metaphorical for psychological reconstruction, which might be most evident in the scene where random people come to the man’s help when a tire of his car gets stuck in a small pit, but, in my opinion, the chosen milieu designates something more primordial. The protagonist even says that “everything good comes from the soil” and evaluates the excavation landscape beautiful. He has appropriately chosen this as his graveyard. The soil thus signifies both life and death. Life comes from it and everything returns to it. In the end, it is soil where the protagonist lays himself on as he descends to his open grave.

The landscape of gravel is almost a character itself in the film. The gorgeous long shots of the protagonist’s car curving in the narrow roads of the hills recur. Even the title of the film, in one sense at least, refers to the aesthetics of the soil. As the third passenger enumerates banal reasons not to kill oneself such as the beauty of sunrise and sunset, he adds the taste of cherries to the list. These reasons are banal, but they are banal because they are material reasons (in contrast to, say, cosmic reasons such as a deity) and as such they are no more banal than any other raison d’être because all of them are ultimately material, belonging to the primal world of the soil. In Kiarostami’s existentialism of facticity, there are no cosmic reasons to exist; there are only cherries, gravel, and bad quality behind-the-scenes footage. In this sense, I believe, the free indirect discourse shots of falling gravel or the dropping boulders in Taste of Cherry are not so much metaphors for the protagonist’s experience, though they can echo his thoughts and vice versa (think of the cast shadow on the movement of the boulders), but rather metonymies for being itself belonging to the material reality depicted.

To further illustrate this, the same point about Kiarostami’s style in Taste of Cherry can be made in terms of his use of sound. Kiarostami uses no non-diegetic music which only enhances the unmistakably materialist soundtrack. At times, the characters’ dialogue is inaudible below the din from the traffic or the noises of the playing children nearby. In every scene by the place reserved for the protagonist’s grave, off-screen sounds of dogs whining are heard. They are diegetic sounds, in the sense that they seem to belong to the fictive world, but their source is also characteristically in the off-screen space since the dogs themselves are never seen. Due to repetition and this emphasis on their concrete absence, the spectator might see the dogs’ whining as symbolic for the protagonist’s pain and suffering, but, the way I see it, however, these sounds are -- like the falling gravel, the dropping boulders, or the rolling empty spray can in Close-Up (see the previous entry in this blog) -- metonymies for the facticity of being. They belong to the (diegetic) reality and do not as such represent anything alien to themselves; for one, they can hardly be interpreted as signs of so-called point of hearing, another mark of internal focalization.

Kiarostami’s “neorealist” style, which emphasizes the impression of continuity, includes a slower editing rhythm. This manifests as something that one might phenomenologically call horizontality. Although Kiarostami uses the conventional shot reverse shot device in scenes with dialogue, he does not use analytical editing. That is to say, there is never a clear, predictable pattern from larger shot scales to smaller ones. Kiarostami’s shots are lingering -- if not strikingly long in the extreme sense of slow cinema -- both in medium shots and in long shots. The camera often follows the car driving from a distance, thus resisting the narrative temptation to cut as the object leaves the frames of the screen space.

These cinematic means of editing and cinematography result in narrative that is horizontal by nature like human perception in general. The horizontality of perception is a phenomenological notion from philosopher Edmund Husserl by which Husserl tries to characterize the spatio-temporal width of perception, the fact that one always intends (or directs one’s mental states to) more than is immediately seen. Horizontality means that there is always more present to a perception of any object than its immediately apparent aspects; for example, a perception of the front side of a house also seems to implicitly entail the possible or forthcoming perception of its rear side. Husserl writes that “the perception has horizons made up of other possibilities of perception, as perceptions that we could have, if we actively directed the course of perception otherwise: if, for example, we turned our eyes that way instead of this, or if we were to step forward or to one side, and so forth.” (Husserl 1999, 44, italics by Husserl).

In the case of Taste of Cherry, Kiarostami’s horizontal narrative enhances the width of presence both in terms of what lies beyond the frames of the screen space and in terms of what will soon be seen in the subsequent shots. By really emphasizing this aspect of cinema, Kiarostami not only echoes André Bazin’s idea of cinema as centrifugal but also comes close to Cesare Zavattini’s neorealist dreams of cinema in real time. With regards to both temporality and spatiality, Kiarostami’s aesthetics of continuity achieves a node of the spectator’s and the film’s time in “objective” space where the screen and the theater meet; it is a rendez-vous of implicated further perceptions belonging to the horizontal systems of every perception. To Husserl’s concept of horizontality, there belongs the idea that one never perceives the other as a mere physical body but always also as a mental, living being. Husserl writes that “I experience others as actually existing and, on the one hand, as world Objects (...). On the other hand, I experience them at the same time as subjects for this world, as experiencing it (this same world that I experience) and, in so doing, experiencing me too even as I experience the world and others in it.” (Husserl 1999, 91, Husserl’s italics). This is another reason why I think the objective elements (the gravel, the boulders) in the potential close-up shots which might reflect the protagonist’s thought processes ought to be seen as a metonymies rather than metaphors; that is to say, consciousness is not wholly separable from reality but an integral part of it. Thus Kiarostami’s realism is phenomenological realism which highlights the interrelation between subject and the world; it is realism of a profound kind, facilitating the ability of Kiarostami’s cinema to achieve intimate truths of human existence which, nonetheless, lie on the surface of the reality of the Lebenswelt, the life-world.

An intriguing example of not only such realism but also specifically its notion of a constitutive interaction between consciousness and reality manifests in Kiarostami’s choice of milieu. In this case, I am not talking about the gravel landscape but rather the dominant space in Taste of Cherry, that is, the car. The car is, of course, a space with its own history in Iranian cinema. Many directors of the so-called Second Wave of Iranian cinema (after the new wave of the 60′s) preferred the car as a location for their films because the car allowed a concrete sense of privacy from officials as a film could be shot while moving around in a city, thus providing a potential escape as well. Kiarostami often films in cars -- think of the prolonged traffic jam sequence in Life, and Nothing More or every shot in 10 (2002). In Taste of Cherry, the car is a closed internal space in contrast to the open external space of the wide landscape. Yet its run-down tires keep scratching the surface of the soil in a fashion that enhances the material nature of Kiarostami’s soundtrack. Therefore, the car is, rather than being isolated, environmentally embedded and engaged. It is, to continue speaking in phenomenological terms, actively dynamic since its movement depends on its driver, whereas the movement of objects in the external space is passive since it does not depend on the driver. As a dynamic interlocutor in a quiet dialogue between the world and the subject, the protagonist’s car turns into a metaphor for the protagonist’s isolation which is not total -- as the earlier discussion on metonymies might have implied, and as it was further elaborated above in the discussion on the horizontality of perception -- as he is a worldly being. The car is the protagonist’s mobile grave which is constantly searching for its final resting place, a space to humanize, space to call one’s own, a space to carry something even vaguely meaningful.

In the end of Taste of Cherry, the protagonist lays himself on such a resting place. He lies on the soil. A storm starts to break. As the man is seen lying on his back in his open grave in the night, Kiarostami cuts from this facial close-up to the Moon hiding behind clouds in the dark sky. The spectator might shed a tear for this subtle passive movement in the environment, but the Moon is not exactly a symbol (say, for virginity, as it is classically seen). The shot is once again an instance of cinematic free indirect discourse where narrative shows something through the protagonist without succumbing into his inner perspective. The subsequent close-up of the man’s face is followed by a cut to black. The storm is breaking and the dogs are howling. Both sounds are essentially diegetic but their origin lies in the off-screen space since the on-screen space is nothing but darkness. In a word, there is no on-screen space. The screen space becomes the grave, an open grave in the sense of the centrifugal nature of the cinema, pointing beyond itself in terms of horizontality. The screen becomes nothing.

This leads us to the iconic ending of Taste of Cherry which was mentioned in the beginning of this essay. The foregoing discussion on narrative, Kiarostami’s use of metonymy, and the phenomenological nature of his cinema was required not only to contextualize but also to truly grasp the ending. It is an ending which has puzzled many and, probably, seems contrary to all reason when it comes to making films, but it is, I believe, a true stroke of genius from Kiarostami. In fact, it seems so contrary that the last time I saw Taste of Cherry in a cinema, I heard one spectator wonder whether the final sequence was a part of the film or not.

The cut from the open grave to the black screen lasting for some thirty seconds could be the end of Taste of Cherry, but in a totally unprecedented manner Kiarostami cuts after roughly half a minute of darkness to 8 mm film footage of behind-the-scenes material of Taste of Cherry. In this footage, the actor playing the protagonist of the film is seen alive and well, Kiarostami and his assistants are seen shooting marching soldiers, and finally the crew drives away from the camera. If the last cut to black from the shot of the protagonist lying in his open grave killed the diegetic space, as the screen space became nothing, then now narrative moves beyond that space into what one might call extra-diegetic space, which, of course, becomes one level in the diegetic universe of the film (and no one can say, for sure, if this sequence was totally staged, for instance).

The spectator could interpret this ending as a metaphor for the character’s death -- precisely a metaphor indeed and not a metonymy, in this case, as we are talking about a cut, a transition from one space via nothingness to another rather than objects in the screen space. Maybe he lied down to die, the darkness of the screen marking the moment of his death, and the resurrection of the screen space in the world beyond marking the detachment of his soul from his body -- either imagined or “real” in terms of narrative. On the other hand, the spectator could interpret this ending of the film as a metaphor for the protagonist’s survival as the man playing him is seen alive and well, a triumph of hope in tone, so to speak. The ending remains open.

Regardless of how one interprets the ending, it seems to articulate another banal raison d’être worthy of adding to the list of sunsets and tastes of cherries: that is, the creation of cinema or art in general. After a heavy story about a man contemplating suicide and people trying to convince him of the worthwhileness of life, Kiarostami opens his hands, so to speak, and embraces the absence of absolute answers. Although apparently contrary to the logic of narrative and dramaturgy, Kiarostami’s cut to the behind-the-scenes footage is a true stroke of cinematic genius. His existentialist humility and his human gesture of admitting the ambiguity of the questions asked and the answers proposed is essentially meta-fictive. In fact, it must be meta-fictive because Kiarostami’s cinema always questions life and cinema simultaneously since they are interrelated.

There are many ways to approach these questions, but I think one useful tool is provided by a set of categorical distinctions by film scholar Richard Neupart. According to Neupart, there are four possibilities to end a film (see Neupart 1995, 33). The first and most conventional possibility is to close the film’s story as well as the film’s discourse. In this case, there is a closure to the story which coincides with the closure of discourse, that is to say, when the story ends, so does narrative. The second possibility is to leave the story open but to close the discourse. This is the classical open end: the film ends but the story lacks a closure. The third possibility is an intriguing one: to close the story but to leave the discourse open which means that the story ends, though the discourse still keeps going. The typical example of this third possibility could be the use of behind-the-scenes footage during closing credits or the famous eight minute ending of nothingness in Antonioni’s The Eclipse (1962) after the story concerning the main characters has elapsed. The fourth possibility is even more obscure: to leave both the story and the discourse open. To Neupart, this concerns films which are meta-fictive by nature; they are films which question the whole process and the notion of making cinema. Neupart’s example is Godard’s Weekend (1967), which ends with the famous continuation of the traditional “fin” at the end of a French film: “fin... du cinéma?”

When it comes to Taste of Cherry, some might argue that it represents the third possibility. In this sense, the story of the film ends but the discourse remains open as Kiarostami continues to show behind-the-scenes footage which, nonetheless, seems connected to the rest of the film in terms of discourse. On the other hand, some might argue that it represents the fourth possibility. In this sense, the story of the film remains open (after all, the spectator cannot be sure whether the protagonist dies or not; that is to say, the central conflict driving the whole dramaturgy remains open) as does its discourse. I believe this is the case in Taste of Cherry. Its story remains open because the dramatic conflicts in the diegetic world remain unsolved. Its discourse remains open because the proposed questions remain unsolved. As it turns out, doubt is cast on the whole meaningfulness of these questions themselves. What is more, this openness of the conflicts and the questions turns into a meta-fictive, non-verbal question addressed toward the film itself and cinema in general -- what is cinema and why cinema? -- both of which remain unanswered, dangling in the semantic void of material reality whose banal facticity both startles and pleases us.

In this way, there is sadness to the end. Whether the protagonist dies or not, it seems that his life or death do not receive any sublimity by means of cinematic means (say, an uplifting piece of music or the ubiquitous darkness in the end without the subsequent behind-the-scenes footage), but rather they collide with something utterly un-romantic. They return to their material being as artificial artifacts, emphasized by the poor picture quality of the 8 mm film used for the epilogue sequence.

So what remains to be said? More and also nothing. Perhaps, as many great thinkers have said before, the act of asking a question is more important than answering it. Taste of Cherry asks profound questions of life without ever even formulating them in a verbal form banal enough to allow intelligible answers to them. It also points these questions to cinema and art by questioning itself. One feels a need to conclude, the enduring desire of all writing about cinema, but at this point it seems trivial. One could say something along the lines “Taste of Cherry is a masterpiece about the absurdity of the will to live,” but maybe, this time, one could accept that Kiarostami’s film is actually so good that it does not need to be forced into something, to be categorized as something. Does this mean I have only wasted my time as well as yours, the reader? Perhaps. Or maybe this is another mundane instance of what one might call the taste of cherry.

References:

Husserl, Edmund. 1999. Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology. Translated by Dorion Cairns. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Original text in French from 1929]

Neupart, Richard. 1995. The End -- Narration and Closure in the Cinema. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

19 notes

·

View notes