#yes the 'start by admitting' was a reference to a lyric in the song cabaret.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

characters I headcanon as autistic and/or ADHD (long post; there WILL be way too much evidence)

Sally Bowles (Cabaret)- ADHD.

I'll start by admitting that she's definitely not supposed to be seen as ADHD. She's a more toned down version of the manic pixie dream girl trope from a musical made in the 60s and set in the 30s. However, I definitely see a lot of signs in her.

Prefers to have a spontaneous lifestyle- often switches between living spaces and lovers.

Enjoys working at the Kit Kat Club, which is likely full of constant stimulation.

Tends to be very talkative.

Depending on the production, she's often almost constantly moving.

Very energetic in certain numbers such as Perfectly Marvelous (which is severely underrated) and (depending on the production) Cabaret.

Again, this one depends on the production, but she is sometimes portrayed as someone who is very emotional.

Caroline Channing (2 Broke Girls)- AuDHD

I'm definitely self projecting here but I do notice signs of both autism and ADHD in her. It's only because I'm self projecting, but I digress.

Autism:

Really good at sorting things. Even her thoughts.

Can be brutally honest at times.

Hyperfixated on coupons once (could also be ADHD).

Very passionate about business, and links everything to a business opportunity. This is definitely a reach (so no you don't have to tell me), but this could be a special interest of hers.

Talks about herself a lot instead of asking about other people unless she's genuinely concerned about their wellbeing.

Doesn't always understand when Max is being sarcastic.

ADHD:

Hyperfixated on coupons once (could also be autism).

Quite impulsive at times.

Talks a lot, which is sometimes a way hyperactivity presents itself.

Very emotional.

One time got distracted because she accidentally searched more gay men instead of Morgan Freeman and started watching makeup tutorials made by gay men.

Max Black (2 Broke Girls)- AuDHD (it's my current hyperfixation what did you expect)

I literally have nothing to say her other than it could just be a combination of trauma and what I like to call Sitcom Personality™️. However, the power of self projection is here.

Autism:

Not very expressive of her emotions, at least through her facial expressions and tone.

Doesn't react to others' emotions correctly ("You need to react when people cry!" "I did react, I rolled my eyes.")

Baking hyperfixation or special interest.

Doesn't seem to be very socially aware and constantly says things she shouldn't.

ADHD:

Failed to file her taxes for years because she kept getting distracted by YouTube.

Very impulsive.

Still emotional even though she doesn't show it through physical expressions or tone (punched cheesecakes because she was mad about Johnny being in the diner).

Very disorganised.

#yes the 'start by admitting' was a reference to a lyric in the song cabaret.#more will be added! it's just very late rn#autism#adhd#audhd#headcanons#my headcanons#hyperfixation#special interests#neurodivergent#2 broke girls#max black#caroline channing#cabaret#cabaret musical#sally bowles

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

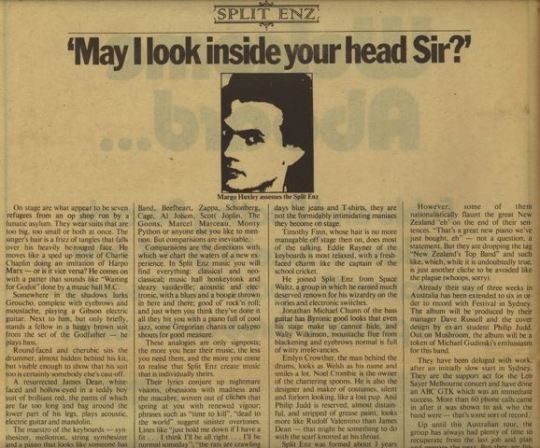

Article by Margo Huxley - early days in Australia, 1975.

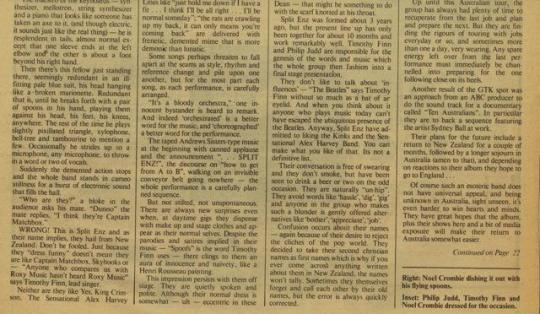

“On stage are what appear to be seven refugees from an op shop run by a lunatic asylum. They wear suits that are too big, too small or both at once. The singer’s hair is a frizz of tangles that falls over his heavily be-rouged face. He moves like a sped up movie of Charlie Chaplin doing an imitation of Harpo Marx - or is it vice versa? He comes on with a patter that sounds like ‘Waiting for Godot’ done by a music hall M.C.

Somewhere in the shadows lurks Groucho, complete with eyebrows and moustache, playing a Gibson electric guitar. Next to him, but only briefly, stands a fellow in a baggy brown suit from the set of the Godfather - he plays bass.

Round-faced and cherubic sits the drummer, almost hidden behind his kit, but visible enough to show that his suit too is certainly somebody’s cast-off.

A resurrected James Dean, white faced and hollow-eyed in a teddy boy suit of brilliant red, the pants of which are far too long and bag around the lower part of his legs, plays acoustic, electric suitar and mandolin.

The maestro of the keyboards - synthesizer, mellotron, string synthesizer and a piano that looks like someone has taken an axe to it, (and though electric, it sounds just like the real thing) - he is resplendent in tails, almost normal except that one sleeve ends at the left elbow and the other is about a foot beyond his right hand.

Then there’s this fellow just standing there, seemingly redundant in an ill-fitting pale blue suit, his head hanging like a broken marionette. Redundant that is, until he breaks forth with a pair of spoons in his hand, playing them against his head, his feet, his knees, anywhere. The rest of the time he plays slightly pixillated triangle, xylophone, bell-tree and tambourine to mention a few. Occasionally he strides up to a microphone, any microphone, to throw in a world or two of vocals.

Suddenly the demented action stops and the whole band stands in cameo stillness for a burst of electronic sound that fills the hall.

“Who are they?” a bloke in the audience asks his mate. “Dunno” the mate replies. “I think they’re Captain Matchbox.”

WRONG! This is Split Enz and as their name implies, they hail from New Zealand. Don’t be fooled. Just because they “dress funny” doesn’t mean they are like Captain Matchbox, skyhooks or - “Anyone who compares us with Roxy Music hasn’t heard Roxy Music” says Timothy Finn, lead singer.

Neither are they like Yes, King Crimson, The Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Beefheart, Zappa, Schonbert, Cage, Al Jolson, Scott Joplin, The Goons, Marcel Marceau, Monty Python or anyone else you like to mention. But comparisons are inevitable.

Comparisons are the direction with which we chart the waters of a new experience. In Split Enz music you fill find everything: classical and neo-classical; music hall honkeytonk and sleazy vaudeville; acoustic and electronic, with a blues and a boogie thrown in here and there; good ol’ rock’n’ roll; and just when you think they’ve done it all they hit you with a piano full of cool jazz, some Gregorian chants or calypso shouts for good measure.

These analogies are only signposts; the more you hear their music, the less you need them, and the more you come to realise that Split Enz create music that is individually theirs. Their lyrics conjure up nightmare visions, obsessions with madness and the macabre, woven out of cliches that spring at you with renewed vigour; phrases such as “time to kill”, “dead to the world” suggest sinister overtomes. Lines like “just hold me down if I have a fit... I think I’ll be all right... I’ll be normal someday”, “the rats are crawling up my back, it can only mean you’re coming back” are delivered with frenetic, demented mime that is more demonic than lunatic.

Some songs perhaps threaten to fall apart at the seams as style, rhythm and reference change and pile upon one another, but for the most part each song, as each performance, is carefully arranged.

“It’s a bloody orchestra.” one innocent bystander is heard to remark. And indeed ‘orchestrated’ is a better word for the music, and ‘choreographed’ a better word for the performance.

The taped Andrews Sisters-type music at the beginning with canned applause and the announcement “... SPLIT ENZ!”, the discourse on “how to get from A to B”, walking on an invisible conveyer belt going nowhere - the whole performance is a carefully planned sequence.

But not stilted, not unspontaneous. There are always new surprises even when, at daytime gigs they dispense with make up and stage clothes and appear as their normal selves. Despite the parodies and satires implied in their music - “Spoofs” is the word Timothy Finn uses - there clings to them an aura of innocence and naivety, like a Henri Rousseau painting.

This impression persists with them off stage. They are quietly spoken and polite. although their normal dress is somewhat - uh - eccentric in these days blue jeans and T-shirts, they are not the formidably intimidating maniacs they become on stage.

Timothy Finn, whose hair is no more manageable off stage than on, does most of the talking. Eddie Rayner of the keyboards is more relaxed, with a fresh-faced charm like the captain of the school cricket.

He joined Split Enz from Space Waltz, a group in which he earned much deserved renown for his wizardry on the ivories and electronic switches.

Jonathon Michael Chunn of the bass guitar has Byronic good looks that even his stage make up cannot hide, and Wally Wilkinson, moustache free from blackening and eyebrows normal is full of witty irrelevancies.

Emlyn Crowther, the man behind the drums, looks as Welsh as his name and smiles a lot. Noel Crombie is the owner of the chattering spoons. He is also the designer and maker of costumes, silent and forlorn looking, like a lost pup. And Philip Judd is reserved, almost disdainful, and stripped of grease paint, looks more like Rudolf Valentino than James Dean – that might be something to do with the scarf knotted at his throat.

Split Enz was formed about 3 years ago, but the present line up has only been together for about 10 months and work remarkably well. Timothy Finn and Philip Judd are responsible for the genesis of the words and music which the whole group then fashion into a final stage presentation.

They don’t like to talk about ‘influences’ – “The Beatles” says Timothy Finn without so much as a bat of an eyelid. And when you think about it anyone who plays music today can’t have escaped the ubiquitous presence of the Beatles. Anyway, Split Enz have admitted to liking the Kinds and the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. You can make what you like of that. It’s not a definitive list.

Their conversation is free of swearing and they don’t smoke, but have been seen to drink a beer or two on the odd occasion. They are naturally “un-hip”. They avoid words like ‘hassle’, ‘dig’, ‘gig’ and anyone in the group who makes such a blunder is gently offered alternatives like ‘bother’, ‘appreciate’, ‘job’.

Confusion occurs about their names – again because of their desire to reject the clichés of the pop world. They decided to take their second Christian names as first names which is why if you ever come across anything written about them in New Zealand, the names won’t tally. Sometimes they themselves forget and call each other by their old names, but the error is always quickly corrected.

However, some of them nationalistically flaunt the great New Zealand ‘eh’ on the end of their sentences. “That’s a great new piano we’ve just bought, eh” – not a question, a statement. But they are dropping the tag “New Zealand’s Top Band” and such like, which, while it is undoubtedly true, is just another cliché to be avoided like the plague (whoops, sorry).

Already their stay of three weeks in Australia has been extended to six in order to record with Festival in Sydney. The album will be produced by their manager Dave Russell and the cover design by ex art student Philip Judd. Out on Mushroom, the album will be a token of Michael Gudinski’s enthusiasm for this band.

They have been deluged with work, after an initially slow start in Sydney. They are the support act for the Leo Sayer Melbourne concert and have done an ABC GTK which was an immediate success. More than 60 phone calls came in after it was shown to ask who the band were – that’s some sort of record.

Up until this Australian tour, the group has always had plenty of time to recuperate from the last job and plan and prepare the next. But they are finding the rigours of touring with jobs every day or so, and sometimes more than one a day, very wearing. Any spare energy left over from the last performance must be channelled into preparing for the one following close on its heels.

Another result of the GTK spot was an approach from an ABC producer to do the sound track for a documentary called “Ten Australians”. In particular they are to back a sequence featuring the artist Sydney Ball at work.

Their plans for the future include a return to New Zealand for a couple of months, followed by a longer sojourn in Australia (amen to that), and depending on reactions to their album they hope to go to England…

Of course such an esoteric band does not have universal appeal, and being unknown in Australia, sight unseen, it’s even harder to win hearts and minds. They have great hopes that the album, plus their shows here and a bit of media exposure will make their return to Australia somewhat easier.

They do not appeal to the younger age groups – “they are no the audience we are really aiming at”. They got a poor reception at the Melbourne Festival Hall Skyhooks concert, where they were first on. The audience didn’t know and didn’t want to. (But I seem to remember once a long time ago, Skyhooks was an “underground” band). But at the Reefer Cabaret, at Unis and the Station Hotel standing ovations are the order of the day.

“There are many ways of saying goodbye:” Timothy Finn lurches into his pitch for the final number – limbs jerking, face twitching at the mercy of some drunken puppeteer; “Goodbye, Byebye, Adieu, See you later, Au revoir…” etc. “…SO LONG FOR NOW”.

Never fear, we have not seen the last of Split Enz. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is A Good Thing.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BAPTISM

His days of envy were over. Or would be by the time this night had run its course. For years he’d watched great singers perform in the concert halls of Boston, Washington, Chicago, New York City. Listened daily on the radio. Had friends who strode out regularly before audiences and sang – whether opera, madrigals, Off Broadway, jazz, gospel, cabaret or pop. He burned to do what they were doing. Above all, to sing the choral masterworks of his gods. The music of Mozart, Britten, Mendelssohn, Ravel. The tenor line in a requiem mass, a sublime Bach cantata.

At the age of 67, three years before this night of his coming out as a singer worthy of a stage, he’d told himself he had in abundance the will and passion that were called for. All he lacked were the skills. He didn’t read music for voice. He’d never sung harmony from a score. And though he had a good ear and could certainly carry a tune, his voice was not trained. He vowed to himself that by the time he turned 70, in the summer of 2015, he would be able to do, in his own way, what his soprano friend Elizabeth, his bass friend Sandy, his baritone friend Paul were all doing – entertain in public as a singer of art songs, arias and great choral pieces.

Throughout the first two of those years, he trekked each Tuesday afternoon from his Brooklyn apartment to the far west side of Manhattan, where Richard Gordon, the vocal coach he’d been referred to, conducted one-on-one voice training sessions in his fourth floor walk-up. And for a year and a half after that, he took beginner, then intermediate, then advanced sight-singing courses at the Lucy Moses School in Lincoln Center. He attended a music theory boot camp and workshops on rhythm and intervals, bought dozens of song scores, hired accompanists for at-home practice sessions, learned tenor parts via YouTube rehearsal files. By the summer of ‘15, he’d researched the New York chorus scene as well and had summoned the nerve to schedule two September auditions: one for a Presbyterian church choir in Brooklyn Heights, another for a 60-member chorale in the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan.

Now it was August and he felt he’d go crazy if he couldn’t escape his sheltered practice environments and at last get out in front of an audience. What did it matter that he wasn’t, and wouldn’t ever be, Domingo? He sounded good to himself and to his teachers. He could pick up a score and start singing, undaunted by varying time and key signatures or dynamics and tempo markings rendered in Italian. He felt confident of holding his tenor line in four-part harmony arrangements. Best of all, he had a safe, low-pressure debut date in mind – the Seventh Annual Upstate Salon in Unadilla, New York, a town in the western foothills of the Catskill Mountains.

For the past six summers he’d been producing this series of living room soirées. He, his wife Jane, and eight to ten of their local friends, for the most part writers and artists, assembled on a late-August evening each year to cook and share a gargantuan dinner, then exhibit, recite and otherwise perform for one another. Edmond, a lifelong painter, always displayed a dozen or so of his latest oils. Alicia, the event’s host and a published poet, read a selection of her nature odes and short prose pieces. Diane, a writer who lived in nearby Oneonta, did the same. Charlie, a nationally known sculptor, photographer and crafter of hilltop aeolian harps regularly gave multi-media presentations. Edmond’s wife Kaima showed her pottery one year and performed modern dance another. Charlie’s wife Martha showed the fabrics and baskets she wove and sold at regional markets. Others played music or delivered dramatic monologues.

What he himself had brought to each of the earlier salons was a one act play – sometimes one he’d written, sometimes a classic piece of comedy he admired. He and a couple of the other guests would present script-in-hand readings, following a brief run-through while the dishes were being scrubbed up. He would show, too, whatever figure drawings and portraits he had done that winter and spring. But as if in the throes of the proverbial itch, he determined to change course entirely at this seventh gathering ... and sing.

He’d packed five song scores for the car trip up from Brooklyn. His plan was to ask Alicia to accompany him on piano and to let her choose a piece from among three show tunes and two opera arias. But on the night of the salon, he learned that her vintage upright was out of commission. No major setback, he decided. What he was looking for here was only a test, after all, the sort of manageable trial likely to provide him some seasoning. Fine, he would go a cappella. And he’d sing not some straight-ahead ballad from Carousel, or even the more forgiving of the two classical numbers he’d brought along, but rather the most challenging of the arias he had prepared at Richard Gordon’s studio: La fleur que tu m’avais jetée, the Flower Song from Act Two of Bizet’s Carmen.

“As Jane knows, and as a few of you may be aware,” he announced once his turn to perform had come and he stood in the center of that ring of friends, “I’ve been taking a serious approach lately to solo and choral music.” Smiles of anticipation throughout the room, for who doesn’t like live singing? And Jane, being Jane, beamed in encouragement. This was all good; he felt at ease. “Here’s something I hope you’ll enjoy.” He passed out sheets on which an English translation of the lyric was printed, waited as his audience looked them over, and began.

He knew not to think when he sang, simply to lose himself in the ghost world of the song and let the joy of self-expression quicken his blood. Yet even as the first few measures of the aria flowed from him like liquid – as softly, as richly as he’d hoped, in fact – he could not help but bask in the fierce attention of these friends he’d known for more than twenty years. Their open faces, their eyes widened in lavish good will. Not a movement in the room, not a sound other than what a broken Don José was saying to Carmen ... that he had kept with him the blossom she’d tossed through the barred window of his prison cell ... and that, though the petals had withered over time, they’d never lost their fragrance.

It would occur to him later that if he’d somehow been obliged to finish singing right there – three or four lines in – strange as that might have seemed, all would have been well. But La fleur is a five-minute aria. One that spans two octaves and climbs to a high b-flat at its climax. And a mere two minutes into the journey that is that song, he felt his breath control begin to falter. It happened at the phrase “et de cette odeur je m’enivrais ...”, the last note of which must be sustained at high volume.

This was troubling. As Don José, he was singing of being intoxicated by the flower’s scent, and so by Carmen’s love. But he couldn’t quite support the note long enough to ensure its full emotional effect. And a shortness of breath, he knew from experience, begets anxiety. Which itself can lead so easily to wavering pitch and wobbly vibrato and graceless phrasing and cracked high notes that make you yearn to be done, to be elsewhere. Worst of all, momentary losses of memory can come along and ratchet up one’s fears to the level of terror – what lyric comes next? �� and threaten to bring the music to a mortifying halt.

One scant phrase from the end, that happened. For when he sang: “Et j'étais une chose à toi ... ” (“I once meant something to you”) and took a stab at that treacherous b-flat on toi, he could not for the life of him remember the aria’s final four words. Here was an instant of unvarnished panic ...... until he did remember, with immense relief, that Don José himself pauses at this very moment, before singing whatever it is he sings.

He took that opportunity to scan the faces of his salon audience, every one of which was turned toward the carpet that adorned Alicia’s floor. Every one except Jane’s. And that was all he needed – not to save this fiasco but at least to finish up with “ ... Carmen, je t’aime!”

There was clapping, yes, it being unthinkable not to applaud at all after someone has performed for you. And each discrete token of appreciation stung him. Each word, brave smile, upturned thumb. Until, after forever, everyone moved on to the coffee and cordials that traditionally concluded their salons. And as he tried to recover, a barrage of thoughts and feelings assailed him. Each registered only for an instant, but so searingly that he knew he’d be revisiting that thought, that feeling, often enough in the days and weeks to come. For now, though, denial was the ticket. He shook off the initial wave of shame. Rejoined the party.

So much to acknowledge and learn from, he eventually found. The shock to his system drove him back fifty-one years to a judgment his first French professor, Emile Telle, pronounced on him in sophomore year of college. “You are good at all of this, Monsieur Quinn,” that crusty Parisian said with a grin. “Yes, yes, very talented. But you are also proud.” The man had played heavily on the guttural French ‘r’ in voicing that final word, thereby freighting his utterance with the heft of prophecy.

It was true, he admitted a day or so later in a bout of self-analysis. He’d never mastered the virtue of humility. And surely pride had gone before his fall at the event in Unadilla. So be it. They’d all gotten past the awkwardness quickly enough. And he knew now what he must do in the run-up to his chorus auditions the following month. Stay focused on the goal. Keep practicing. Do his best to get his head and ego back in order.

0 notes