#wildlifebiology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

Fascinating Nature: Oxpeckers Cleaning Gazelle's Head! 🐦🦌😜#shorts #anima...

#EcosystemInteractions#wildlifeeducation#GazelleConservation#naturalhabitats#AnimalPartnerships#wildlifebiology#animal photography#animal lovers#animals#gazelle#oxpecker#nature photography#nature photographers#nature lovers#national geographic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hunters Vs Wolves

Recent billboard in Northern Minnesota, paid for by the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association, Sep. 2023.

A Sign of the Times

This photo surfaced on Facebook in a Voyageur's Wolf Project post of a billboard paid for by The MN Deer Hunters Association, blaming wolves for the loss of 54,000 deer fawns every year in Minnesota. Using words like 'devour' and the sweet image of a young fawn, the billboard appears to argue for the management of wolf populations to protect Minnesota's deer herds - for the benefit of more deer available to Minnesota deer hunters.

The Voyageurs Wolf Project brings up several concerns regarding the legitimacy of the numbers on the board, which will further be explained below. This post will also explore the research of wolf predation on deer fawns, and wolf and deer ecology.

To begin, we will start by discussing number-hurling, one of the most common misused of scientific information in the media.

Number-Hurling

Number-hurling is the act of using a number, statistic, or other forms of data to support a claim. The difference between this and sharing scientific information is that not much (if any) further information is given.

Numbers without context are arbitrarily. Take this quote: "150,000 people die every day". That seems like a lot - until you consider that the human population on Earth is approaching 8 billion, meaning .001% of the human population dies every day.

With that in mind, the next question should be: what does 54,000 mean for deer in Minnesota?

Deer, Deer, Deer

Most sources estimate Minnesota has a white-tailed deer population of about 1 million, give or take a ten-thousand. Since it is difficult imposable to count the exact number, most population information comes from statistical models and hunter harvest data.

Links to Deer Population information:

Deer Friendly

MN DNR website

AZ animals

This PDF talks more in-depth about estimating animal populations using methods like Plot Sampling and Distance Sampling. These methods involve surveying a randomly selected area for the animal. The number of animals counted is then divided by the survey area, presenting an animal density.

There are 86,943square miles in Minnesota. If we randomly selected 1-square-mile study areas across the state, and calculated 11.5 deer/square mile, that would give us about 1 million animals. The animals are obviously not perfectly spread out across the state, but we have a population estimate for statical purposes.

54,000 divided by 1 million and multiplied by 100 is 5.4. This means according to the billboard, wolves killed 5.4% of deer in a single year. But there's a problem with this math - the number 1 million references all deer, while the number 54,000 only refers to fawns. In order to find out what percentage of fawns are being killed by wolves in Minnesota, we have to estimate of the population of deer under 1 year old.

How Many Fawns are in Minnesota?

Disney's Bambi, 1942

The truth is - we don't know how many fawns are in state.

Fawn populations are more difficult to estimate than adult populations because fawns >6months old are very good at hiding. For the first couple weeks, a fawn's main survival method is curling up in the grass and hiding. Conducting any sort of survey to count fawns by hand is simply not efficient due to the number of fawns that would be missed.

A mature doe has 2 fawns per year on average (young mothers with smaller body sizes typically have 1 fawn, and older, healthier does have twins, or sometimes 3 - 4 in a single spring). So, why can't we multiple 2 fawns for every adult female deer? We don't know the number of female adult deer either.

Even if the sex ratio of a population was 1:1 (one male for every female), we don't know how many of those animals are mature. If we tried to multiply 2 by half of the population, we would be assuming that female fawns are also giving birth to two fawns. The ratio is most likely not 1:1 either. A healthy deer population has more females than males, since they reproduce polygamously. (More males than females leads to more reproductive competition, which could reduce survival rates of mature bucks).

For Heaven Sakes - What DO We Know?!

We can estimate fawn survival rates. This website from the University of Georgia talks in depth about whitetail fawn research and methods.

A common tactic is to use VIT's on mature does during the winter. In the spring when the doe gives birth, the tracker falls out and sends location data to researcher. Using the data, researchers find the newborn fawn, take measurements, and fit it with a radio collar to monitor it's movements. The collar expands as the fawn grows, and if the fawn survives after the study ends, the collar falls off. If the fawn dies during the study, the collar sends out a mortality signal after a period of non-movement.

Read more about fawn mortality studies and how they impact fawn survivability here.

These mortality studies cannot be used in estimating fawn population for a couple reasons.

The location the fawns are found at is not random. The randomized selection of study areas prevents skewered data. If we count deer at a known feeding location, and use that survey data to estimate the population of other locations, that data would reflect only the area where deer are being feed. In other words, the population estimation would read as if deer have food everywhere - which they do not. Food resources are not equally distributed everywhere. There are places animals go often and places they avoid entirely. Randomized location provide a middle-ground. In monitoring surveys, the priority is to collect as many fawns as the survey needs. Researchers will purposefully choose locations they can catch the most does (over bait, at a water source, along prime bedding and feeding habitat).

There are a limited number of fawns. Part of the goal of a survey is to count as many animals as possible. In mortality surveys, the opposite is true - use as few animals as possible. Wildlife research is bound to the same laws and guides as laboratory animal research under the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), along with state and federal regulations. The goal of any research project regarding animals is to be as non-invasive as the study allows, and use as few animals as possible, or substitutes for live animals whenever possible. Read more about the 3R's in Animal Research.

HOWEVER - data from fawn mortality studies can give us information about wolf predation.

This paper from the US Geological Survey looks at mortality rates of white-tailed deer fawns who were predated on by wolves and black bear in Minnesota in 1994. In this study of 21 tagged fawns, 51% were predated on by wolves, and 49% were predated on by black bears. This paper from Todd Fuller also points to wolves being the biggest cause of mortality on the sampled fawns.

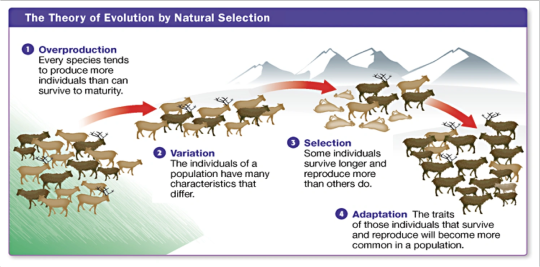

Natural Selection At Work

Overproduction example in caribou

By now, we've all heard of Charles Darwin and his theories of evolution and natural selection. Part of natural selection regards overproduction.

Sea turtles, rabbits, insects, and fish are all examples of animal that produce more offspring in a single breeding event than can reasonably survive. This overproduction is a natural remedy to predators who will eat the excess offspring before causing a dip in the population.

This is why researchers make a distinction between fertility - the number of young that are born to an individual, and recruitment - the number of young that reach sexual maturity. As cute as those baby animals are - they don't do much for a population until they reach the age they can breed. If a population is decreasing, fecundity, fertility, and recruitments are all factors that should be investigated.

With all that in mind, we have no idea what the population of deer fawns is in Minnesota, therefor, the number 54,000 can not give us any information, aside from the fact it is only 5.4% of the total estimated deer population.

Where did 54,000 come from?

Photo from the Voyageurs Wolf Project Trail Camera

According to the International Wolf Center, there are about 2,699 wolves (give or take 700) in Minnesota as of the 2020 Wolf Survey. We could estimate the number of fawns killed by wolves by multiplying the number of fawns an individual wolf kills by the total number of wolves. However, as the Voyageurs Wolf Project points out, that is also a difficult number to figure out.

According to a Wisconsin News article, wolves kill 17 - 20 deer per year (no distinguishment made between fawns and adults). This study from Northern Michigan University claims 12 wolves killed 217 fawns over the course of 4 years. That means that each collared wolf ate 18 fawns - over the course of 4 years. Just for laughs, if we assume each individual wolf killed the exact same amount of fawns every year, that means that one wolf killed 4.5 fawns in a single year.

Search "how many fawns do wolves kill a year" and you will find a string of news articles with 'he-said-she-said' quotes and blog threads of passionate deer hunters. When it comes to raw data from researchers in the field, the answer becomes illusive. The fact that non of these estimates repeat is as big of a red flag as you can get in the science world, as reliable experiments have repeatable data.

In their post, the VWP referenced a paper that estimated wolves killed 17-20 fawns in Upper Michigan. If there are 2,700 wolves in Minnesota, multiply that number by the number of fawns killed, and you get 45,900 - 54,000. The billboard strictly assumes that each wolf kills 20 fawns per year. However, the statistic of 17-20 fawns per wolf was pulled from an article that made no distinction between fawns and adult wolves. Not only is the 54,000 based on questionable sources, but the sources it is pulled from makes it unreliable for not distinguishing between fawns and adults.

Every Year, a Wolf Counts to Twenty and then Stops

Funny enough, the billboard leads one to believe that the number of fawn killed by deer each year is a static number. It is not. How many fawns a wolf kills changes year to year, and depends on multiple factors.

In their own surveys of wolf kills, VWP saw breeding pairs kill more fawns than single wolves. This makes sense - breeding animals require higher calorie intact while pregnant and nursing.

It is also well-known that wolves change their predatory behavior depending on resource availability. In late summer, fawns are strong enough to follow their mothers instead of hiding, so wolves in northern Minnesota will turn to eating beavers, fishing, and even eating berries. Late summer is a particularly lean time for wolves, and is when most wolf pups die of starvation. This paper from Scandinavian research on wolves hunting moose determined that the age of the breeding male was a significant factor in a hunt's success, meaning older adults have more experience.

Lean Summer Pup, via Voyaguers Wolf Project Trail Cams

One important factor in fawn survival to consider is the health of the mother. Though they are born precocial, fawns are highly dependent on their mothers for the first couple of months on their lives, and typically stay with their mothers for their first year. Not only are they given food and groomed, but they learn foraging behavior and predator avoidance. This article goes into dept about how maternal health and dominance can affect survivability of fawns.

Another variable to consider is habitat. Deer can live in a wider variety of habitat that wolves and other predators can. Wolves, black bear, and mountain lions prefer habitat away from busy metropolitan areas, whereas deer can live in wooded patches of suburbs in the middle of a small city. Fawns living in these areas would not be predated on by wolves because there are no wolves around (though there are coyotes). This article talks more in depth about the different mortality rates of different habitat types of whitetail deer.

In Summary

While its known wolves consume a lot of fawns, their predation rates on fawns change through out the year, and vary by habitat, season, and experience. Fawn survival rates are also influenced by environmental factors and the health and dominancy of the mother.

The number of fawns killed by wolves each year is not a static number. There is little evidence to defend 54,000, and even if it were accurate, it is insignificant since the population of fawns and the birth rate of fawns in the state of Minnesota is unknown.

Wolves killing deer fawns in Minnesota is only one line in a vast ecological web. No single factor has ever been recorded causing a significant decline in a species. When a species is declining, there are always multiple factors at play.

Deer vs Vehicles

According to the MN Office of Traffic Safety, between 2016 and 2020, there have been over 6,000 vehicle collisions with deer on the road. 1,000 of those incidents involved serious injuries or fatalities to the people in the car.

The MN DNR website says in 2022, the harvest report was 170,000 deer taken by hunters - which is also 7% lower than the harvest rate of 2021. Even then, that number is significantly higher than 54,000.

The billboard also mentions nothing about the predation of black bear and coyote on deer and fawns. Coyotes are significant because unlike wolves and black bear, they can live closer (and even within) city limits, meaning they can affect deer populations in places wolves and bear cannot.

The Bigger Message

The opposite of the previous billboard.

The purpose of this post is not to villain-ify the MN Deer Hunters Association or glorify wolves, but to encourage people to ask bigger questions when being thrown vague information.

**Opinions Below**

Wolves serve a role in the ecosystem that no other species, including humans, can fulfil. While they should not be evicted from the landscape, this doesn't mean hunting them should never be allowed.

As important as wolves are, they do often cause conflict over livestock, and people's general fear of the animals. Allowing controlled hunts may mitigate potential conflict as well as reinforcing a fear of humans - a thing that may help keep the species alive.

The bottom line - whether or not we hunt wolves is a decision based on our values of wildlife. We need to ask ourselves: what is important to me? Why do I think that is important? What is the information I base my values on?

Answering those questions is the first step we can all take to protect ourselves against number-hurling and make informed decisions about ourselves and our world.

#wolves#wildlife#wolf#wolfpacks#animals#carnivors#science#ecology#research#wildlifebiology#biology#nature#deer#white tailed deer#minnesota#ecosystems#biodiversity#conservation#long post#long reads

1 note

·

View note

Text

#AnimalBiology#Biotechnology#AnimalHealth#Research#Conservation#GeneticEngineering#STEM#WildlifeBiology#ScienceCareers#AnimalProduction

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

if you speak one (1) bad word about bats you can catch these hands

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species Spotlight: Hawaiian Duck

Article by Elena Fischer, External Affairs Kupu AmeriCorps Intern with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

A koloa maoli swims in a vegetated pond. Photo by Brenda Zaun / USFWS

Scientific Name: Anas wyvilliana Hawaiian Name: Koloa maoli Common Name: Hawaiian Duck Status: Endangered

In the days of ruling chiefs in Hawai’i, koloa maoli led the blind chief, Imaikalani, in battle toward many victories. Their calls alerted him to which direction enemies approached, so he could strike out with his spear. These Hawaiian bird guards made it possible for Imaikalani to continue fighting with great strength and skill, for which he was known for.

There are only two duck species native to Hawai’i: the Laysan duck and the Hawaiian duck. The koloa maoli is the only one found on the main Hawaiian islands and exists nowhere else on earth. However, this unique species is being jeopardized by a unique threat: hybridization or cross-breeding. Hope still exists, though. On Kaua’i, pure koloa still thrive, and successful reintroductions to the other Hawaiian islands allow koloa to swim in wetlands once more.

Habitat and Range

Koloa maoli can be found from sea level up to 3,000 feet elevations on all of the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho’olawe. They reside in manmade and natural wetlands, river valleys, flooded grasslands, mountain streams, and ponds. Water less than 10 inches deep are preferred foraging sites, with grasses nearby to graze on. Dense shoreline vegetation - like ferns, shrubs, and bunch-type grasses - are needed for nests.

A profile view of a koloa maoli standing. Photo by USFWS

Historically, the koloa maoli populated all of the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho’olawe and Lāna‘i. Their decline isolated them to Kaua’i, where the only naturally occurring population exists today. Since then, it has been reintroduced to O’ahu, Hawai’i, and Maui, and have populated Ni’ihau as well. However, the only population of pure koloa exists on Kaua’i, for many of the other populations have cross-bred with mallards.

Diet and Life Cycle

Much of their generalist diet is opportunistic, including: aquatic plants, seeds, and grains, insects, green algae, tadpoles, and aquatic invertebrates like mollusks, snails, and crustaceans.

Koloa maoli may nest year-round, but the main breeding season occurs between January and May. Females lay 8 to 10 eggs in a nest placed in dense shoreline vegetation lined with down and feathers. After about 30 days of incubation they hatch, and after 1 year the koloa are ready to breed. Overall, their lifespan is up to 18 years.

Males and females have orange legs, feet, and an overall mottled brown body. They have green to blue secondary wing feathers with white borders. Adult males usually have a darker head and neck feathers, which are sometimes green. Females have a dull orange bill, while males have more of a brown bill.

A koloa swims in the water. Photo by USFWS

Threats to the Species

Because koloa nest on the ground, they are especially vulnerable to mongooses, feral pigs, cats, and dogs. Their eggs can be taken by these predators as well as cattle egrets, rats, and Samoan crabs. Chicks are also preyed upon by bullfrogs, ‘auku’u (black-crowned night heron), and bass. Most of these predators are non-native and invasive. Avian diseases like botulism also pose a threat to koloa.

Historically, hunting and loss of wetlands decimated the population. Habitat loss is still a concern as agriculture changes, oil and fuel spills contaminate wetlands, invasive plant and animal species alter the landscape, and hydrology is altered for flood control. These threats and hybridization with other duck species--especially non-migrating mallards--are the most dangerous to koloa populations.

A profile of a koloa maoli at Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Christopher Malachowski / USFWS

Reason for Hope

Ongoing research and monitoring are important actions for conserving koloa maoli populations and wetland habitats. Kaua’i maintains a distinct population of pure koloa, which is hopeful and in part due to active collaboration between state, federal, and non-profit wildlife workers. These collaborations include: removing feral mallards and invasive predators from the wild so that native koloa outnumber them, and habitat restoration. Education and outreach is also a key part in bringing awareness to the public about how to protect endangered waterbirds and ecosystems.

Where You Can See Them

Hanalei NWR

Hulēʻia NWR

James Campbell NWR

Keālia Pond NWR

Pearl Harbor NWR

#conservation#nature#birds#endangered#savingspecies#ducks#hawaii#pacificislands#refuges#birding#ornithology#wetlands#waterbirds#usfws#biology#wildlife#wildlifebiology

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

#wrinkles#primate#primates#primates terrestrialanimal#primates wrinkleface#wildlife#skin#wild#wildlifebiology

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Invite me a Coffee!

🙏

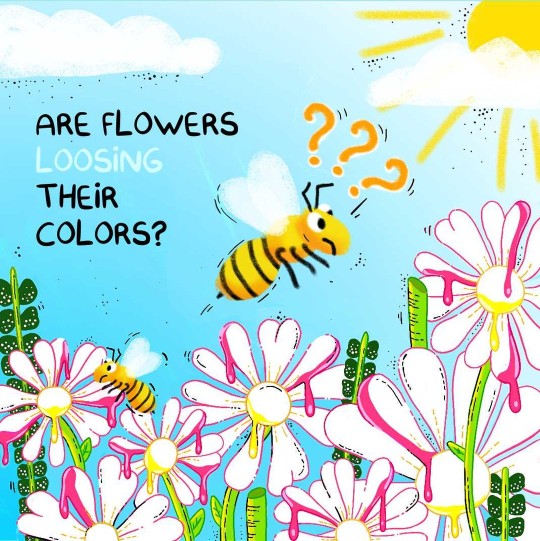

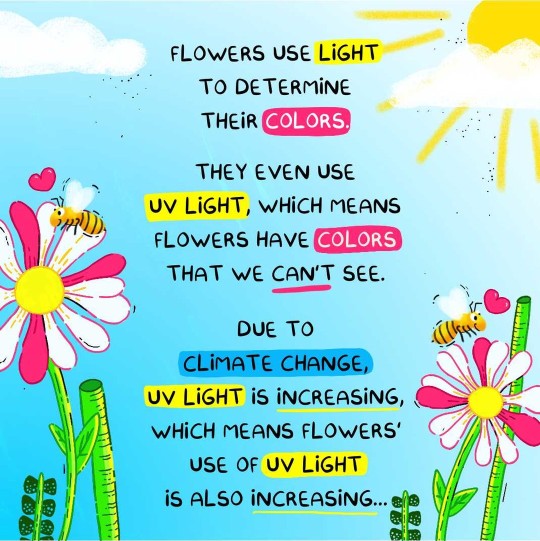

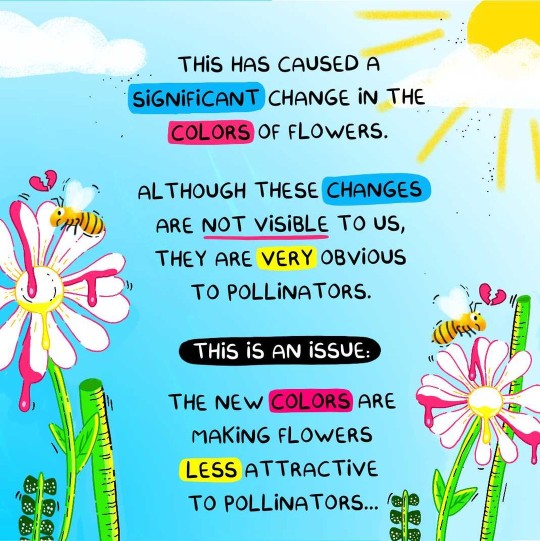

❣pls share if you can🙏❣👉 Hello!!! Today I bring you a collab I did with @anosmiciris, make sure to check her account and her amazing educational content. Can you guess who did what? Well, @anosmiciris came up with the concept and text and she gave me her amazing lineart and textures to work with. Then I added the bees, background and some color. I had a lot of fun working on this one and I learnt a lot from the feedback we gave to each other. It took me out of my comfort zone for sure :) What do you think?

. . . .

Insta post

#savethebees🐝#savethebees#savethebeessavetheworld#protectthebees#backyardbees#pollenators#beesofinstagram🐝#beekeepinglife#saveourbees#ilovebees#beelife#beelover#honeybees#pollinator#bees🐝#beekeepersofinstagram#scicommunity#sciencecommunication#scicomm#wildlifebiology#scienceillustration#scienceart#sciart

0 notes

Text

Poster wins at TWS

Congratulations to undergraduate widllife biology student Sarah Gaulke! Sarah won award for best student poster at the recent meeting of the Montana chapter of The Wildlife Society for her research on "Where do all the bats go? Do bats hibernate in talus slopes?"

Sarah in the field. Photo by Lione Clare.

Her research is studying if bats hibernate in talus slopes. Sarah says, “I was not expecting to win the award, so I was really surprised that my poster got picked. Its been such a fun research project to complete and I am especially grateful to my great advisers who have been helping me with the project.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

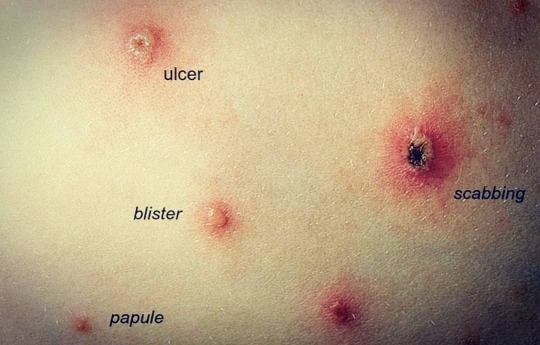

MedClino 👨🏻⚕️ Follow 👉 @devrana4522 ✅ . #biology #microbiology #molecularbiology #biologymemes #cellbiology #biologyteacher #biologynotes #wildlifebiology #biologyclass #biologyislife #neetbiology #humanbiology #ncertbiology #biologystudent #microbiologylab #cellularbiology #medico #medicos #futuromedico #medicolife #biologyfacts #biologylovers #nature #mysteriousbiologyy #devrana4522 (at India) https://www.instagram.com/p/CKQD9CPhHiU/?igshid=b7t0f56nfjea

#biology#microbiology#molecularbiology#biologymemes#cellbiology#biologyteacher#biologynotes#wildlifebiology#biologyclass#biologyislife#neetbiology#humanbiology#ncertbiology#biologystudent#microbiologylab#cellularbiology#medico#medicos#futuromedico#medicolife#biologyfacts#biologylovers#nature#mysteriousbiologyy#devrana4522

0 notes

Photo

My daughter @pianosaurus and I just finished installing a bat house for this summer. Her amazing hand-made gift for me for Christmas. I have the best #family ever! #wildlifebiology #wildlifebiologist #bat #bats #family #familytime (at Kansas) https://www.instagram.com/p/CJT3WVxAcRh/?igshid=tg1pembl9q4k

0 notes

Text

Tundra Trouble

A dramatic population increase in “Light Geese” is threatening sensitive tundra habitat.

What are Light Geese?

"Light Geese” are actually three separate species of goose named after their mostly-white plumage. They include...

Ross’s Goose

The Greater Snow Goose

And the Lesser Snow Goose.

The main different between these birds is size (which can overlap) and slight variations in color. If they are this hard to differentiate in photos, imagine how it much be for duck hunters to identify them. Don’t worry! None of these birds are threatened in any way. In fact, the problem is the exact opposite...

Tundra Geese

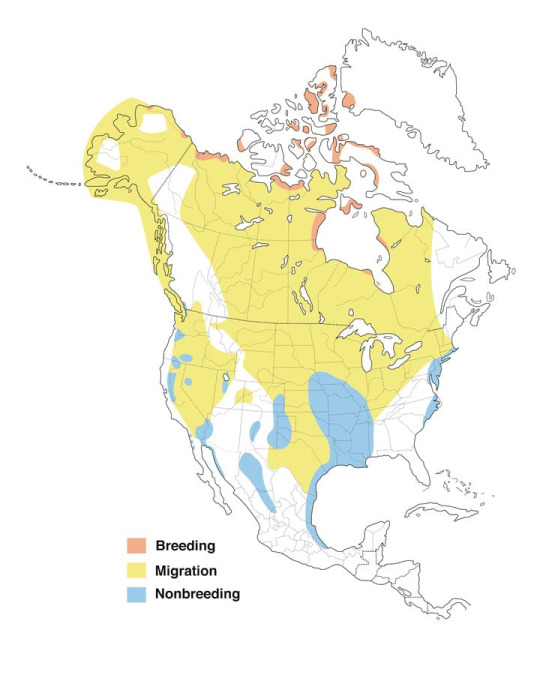

All three of these species breed and nest in the tundra habitat of North America.

The little spots of red on this map signify where the geese nest in the spring. All three geese nest in the same kind of habitat: Tundra.

Now, let’s talk about Tundra.

Tundra is a kind of biome found in cold climate or very high elevations. It is dominated by mosses, roots, and tubes, all ‘short’ plants without deep roots. This is because of a permanently frozen layer of the soil, known as permafrost.

Plants that live here also have to deal with low precipitation, and a growing season that can lasts between 50 to 60 days, or about 2 months. This makes the biome incredibly fragile. If something were to come along and remove all the plants or disrupt the soil, it could take many years for the foliage to recover, if it does at all. Compare this biome to a place with a longer growing season, like the Midwest United State. All the grasses can be removed by grazing and burning, and within the same season, new seeds can take root, and within a couple of years, the grassland is completely back to normal. This is why oil and mining projects in the artic are a big deal, because the kind of damage we see them cause in relatively robust ecosystems will be so much worse in a tundra.

Tundra’s have relatively low biodiversity - there’s only a handful of species that live there in the productive months, and even less in the winter. However, it is a major producer of birds, especially migratory species. Breeding habitat is critical for every species. Tapering with it can directly alter a population’s ability to replace itself with the next generation. It is far more effective to reduce a population by tapering with habitat than removing individuals through hunting.

Light Geese and the Tundra

Like I said earlier, all three species of ‘light geese’ are not threatened. In fact, their population has boomed significantly. Since the 1970′s, the population of light geese has grown by more than 300 percent, and continues to increase by 5 percent each year. According to an article on Ducks.org, waterfowl managers estimate the total population is up around 17million.

Now, is this actually unnatural based on science? It’s hard to say. We don’t really know if this population number matches historic numbers, because we didn’t really take bird surveys until the late 1900′s. Some bird populations, like the extinct carrier pigeon, was so big they would supposedly black out the sky. Maybe, ecologically, we are suppose to have millions of light geese. But there is one thing we do know: they are over-grazing the tundra.

That little square of green once covered a much larger area. Researchers protected it with nets to keep geese out, and all the red in the picture is bare overgrazed soil. Geese don’t just eat the green, the dig up the roots, preventing new growth. Once an area is grazed up, the flocks move to another green space and repeat the cycle. There is nothing much left in terms of food or habitat for other animals on the tundra.

But how?

Nature has ways of balancing populations with available resources. When resources are used up, populations go down until resources go up again. So how did the light geese population rise to the point of environmental destruction? If you guessed agriculture, you’re right!

The later half of the 1900′s came with a boom of farmer productivity thanks to new machinery and chemicals. It helped support a booming human population, and apparently, geese as well.

Usually, migratory birds loose weight during the migration. They have to depend on their fat storage for through the summer and winter to make the 1,000m+ trips. It serves as an important environmental pressure: only the best equipped birds will survive the trip, and have the opportunity to pass on their genes. Lack of food fuels competition between individuals to establish dominance or territory, and at the same time reduces competition as it weeds out unfit individuals. Take the pressure away, and you are a step closer to the light geese problem. Light geese actually gain weight during their migration thanks to all the food available. By the time they return to their nesting ground, a lot of individuals are healthy enough to breed and rear offspring.

The parental habits of light geese are another piece in the problem puzzle. They all practice lifelong monogamy, and both parents are constantly around to guard the young. The young themselves are precocial, meaning the are fluffy and walking around almost immediately after hatching. They can even feed themselves. The only thing the parents need to do is fight off predators - and geese do this exceptionally well.

There are nest predators, like owls and foxes, but they are only able to take so many. Predation alone never has much of an effect on a population - it has to be coupled with a signifanct habitat factor. For example, if you released a fox into a small pen of 10 geese, the fox would immediately reduce the population in the pen. But, if you released a fox onto a large plot of land full of 100 geese, the single predator would never be able kill all of the geese. This is of course, a small-scale example.

Another problem is the flocking. Snow geese flocks can easily exceed a hundred individuals. This makes it easy for hunters to shoot a large amount of birds, but the thing is, they have to get the birds within range first. Duck hunters lure flocks over a body of water by setting out wooden decoys. Since birds feel safer in large numbers, they are drawn to the groups of fake birds. This works if you, for example, put out two decoys, and it attracts a lone duck. However, a flock of over a hundred is not going to find any reason to join a fake flock of 2. To decoy for geese, hunters need a lot of decoys, which is more expensive and time consuming.

Geese are also uncannily smart. They live long lives and can remember places where they were shot at, so avoid them in the next years. That means that most geese that end up shot by hunters are the younger, inexperienced ones who do not contribute much to the population anyway.

Solutions

Managers and researchers are currently searching for ways to fight this problem and protect the tundra, while also not totally wiping out light geese populations. One of the most effective ways to reduce the population would be to disrupt the breeding habitat, but that’s option is not likely. Remember: the tundra is a delicate ecosystem. No disturbance could be significant enough to affect the light geese and not effect other species. Targeting food supplies isn’t realistic either - we can’t poison the tundra grasses, and we can’t throw giant nets over crop fields.

The usual solution to overpopulation of a game animal is lessening hunting restrictions. Hunters can take over a hundred geese in a season - if they can get a flock within range. But that leads to another issue - who wants to carry, clean, and process over a hundred birds? Ammunition availability and prices are another concern.

Another factor that makes any management work in the tundra difficult is accessibility. There are few towns and fewer roads that give people access to nests, so sending in people or dogs to collect/destroy them isn’t always a practical option. Article on possible solutions.

Fish and Wildlife’s suggested lists of actions:

Expanding hunting seasons/limits

Expanding hunting methods (allowing electronic callers).

Far north harvesting.

Egging.

Increase incentive to harvest by award programs, donations, market hunting.

Improve private land access.

Information and education programs.

Bird trapping and culling by wildlife managers.

Refuge management.

Sources

https://www.fws.gov/birds/management/managed-species/light-geese.php#:~:text=Ross's%20geese%2C%20lesser%20snow%20geese,to%20remain%20at%20high%20levels.

https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/exhibits/biomes/tundra.php

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13280-019-01308-5

https://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/pdf/management/snow-geese/light-gooseFEIS-QAs.pdf

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-46487-z

https://www.wildfowlmag.com/editorial/whats-the-best-method-to-control-the-snow-goose-population/280168

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Learn BIOLOGY @tute.in . For more educational posts Check out @tute.in . @tute.in in is a online learning platform which improves student outcomes from Grade 3 to Grade 12 for IB, CBSE and ICSE and Grade 3 to A level for IGCSE in over 30 subjects (core subjects like English, Math and Science along with the supplementary subjects like Social Science, Business Studies, Law etc), deployed by schools as intervention, enrichment, catch-up or alternative provision. . . #sciencefacts #biologymemes #biologystudent #biologymajor #bisons #biologyteacher #biologynotes #biologylab #tiger #biologyclass #india #bisonpride #wildlifebiology #humanbiology #biologyjokes #plantbiology #biology🔬 #biologyislife #biologyart #biologyofbelief #biologylife #biologystudents #biologynerd #biologylovers #biologyfacts #biologyoftheuniverse #biologyeducation #biologymeme https://www.instagram.com/p/CDIinXMp5Qe/?igshid=13t2z42pwxecu

#sciencefacts#biologymemes#biologystudent#biologymajor#bisons#biologyteacher#biologynotes#biologylab#tiger#biologyclass#india#bisonpride#wildlifebiology#humanbiology#biologyjokes#plantbiology#biology🔬#biologyislife#biologyart#biologyofbelief#biologylife#biologystudents#biologynerd#biologylovers#biologyfacts#biologyoftheuniverse#biologyeducation#biologymeme

0 notes

Text

i’m more starved for entertainment than i thought because i was positively delighted when my natural resource prof said “moose use” in lecture today, so much so that i repeated “moose use!!!” out loud in my empty room

#uh yeah moose use i guess#moose#onlineclass#wildlifebiology#it was describing how to tell if moose had been in the area

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beautiful day out in the field. First time since mid-March due to COVID-19. A mountain bluebird was very friendly. Also got close to elk, meadow lark, and a very evasive garter snake. #nevadawildlife #nevadawildflowers #wildflowers #bluebird #elk #wildnevada #travelnevada #optoutside #mountains #mountainsarecallingandimustgo #elkocounty #nevada #wildlifeofinstagram #wildlifebiology #wildlifebiologist #forestservicelife #forestservice #nationalforest #humboldttoiyabenationalforest #humboldttoiyabe (at Independence Mountains) https://www.instagram.com/p/CCE_D9nFt7B/?igshid=1jzqx2glf388d

#nevadawildlife#nevadawildflowers#wildflowers#bluebird#elk#wildnevada#travelnevada#optoutside#mountains#mountainsarecallingandimustgo#elkocounty#nevada#wildlifeofinstagram#wildlifebiology#wildlifebiologist#forestservicelife#forestservice#nationalforest#humboldttoiyabenationalforest#humboldttoiyabe

0 notes

Photo

A Goose Citizenship Law This Comic is based on the article that was published in The Hindu, today. Title: Greylag Goose likely to enter TS list of birds. Excerpt: “This is the third recorded sighting of the large-sized bird in Telangana, which makes it ‘eligible’ to be the latest addition to the state’s exhaustive list of birds.............As per scientific and acceptable norms, a species has to be seen three different times in three different places, or by three independent observers, before it can be accepted as an addition to a State’s list......These could be the birds that have been blown off course by strong winds or rain during flight...” @the_hindu #greylaggoose #wildlifebiology #birder #birding #comics #birds #illustration #illustrator #pijicomics https://www.instagram.com/p/B7D7Vp5p9pB/?igshid=1gtwdt6lkbnyf

0 notes