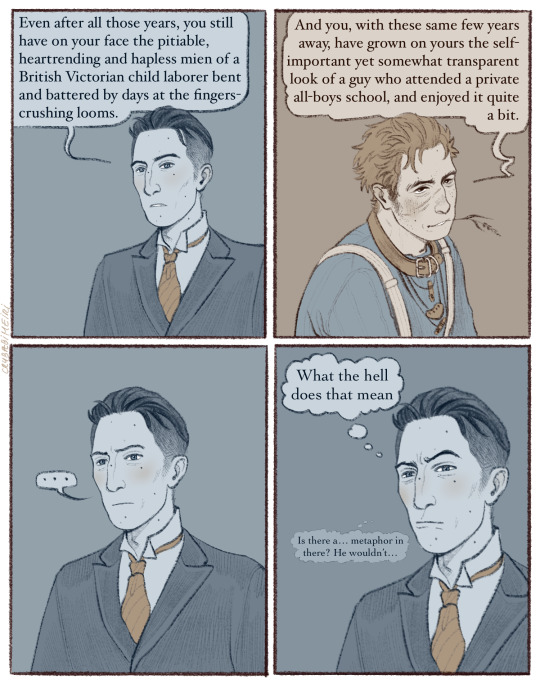

#while the the industrial revolution; which was marked by the use of child labor AND more legislation over it; predates the victorian era;

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the bickering habit

#well i know. personally i know.#''ok oxford goer''-voice of a guy who hasn't stepped foot in an educational institution and is slowly starting to become literate around 20#this is a post-canon thing but not far enough in the future to have fit day 8 ''10 years later'' prompt so... on its own it goes#notkin#notkin pathologic#khan kain#he sees the type of person you are#pathologic 2#i'm of the hashtag opinion patho takes place in the 1910s at the earliest (patho 2 bachelor route looks like it's closer to the 1930s) so#by that point ^ the ''victorian era'' had been over for over 10yrs#while the the industrial revolution; which was marked by the use of child labor AND more legislation over it; predates the victorian era;#it was still ongoing + culminated during queen Victoria's reign (she also implanted many laws to minimize some forms of child labor)#so. victorian orphan + child laborer venn diagram is real and historically-congruent#inheriting the earth patho tag

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 5: The Chocolate Factory Revolution: Technology and the Ghirardelli Legacy

The technological revolution in the chocolate industry occurred in the 19th century, transforming an artisan luxury into a mass-market commodity. Inventions in the production process have not only democratized the consumption of chocolate but have also created global brands, several of which remain household names today. Among such companies is Domenico Ghirardelli, whose biography was the closest to the combination of innovation and entrepreneurship in the Industrial Era.

A critical achievement in the production of chocolate was when a chemist from Holland by the name of Coenraad Johannes van Houten developed a hydraulic press in the year 1828. Fundamentally, this hydraulic press separated cacao butter from the Cacao solid, providing a fine powder that could mix well with other ingredients. In this case, the innovation of mixing greatly changed the texture and consistencies of chocolate; therefore, over time, it allowed for drinking chocolate and chocolate bars to be made. Essentially, this technological development also reduced production costs, making chocolate more accessible to the growing middle class.

Besides, industrialization restructured how chocolate was made. Steam-powered machinery automated grinding, mixing, and conching, increasing production capacity tremendously. Firms such as Cadbury and Nestlé took full advantage of the new technologies to manufacture standardized products with predictable quality. By the middle of the 19th century, chocolate factories were producing confections on a scale unimaginable previously and met worldwide demand for this once-exclusive indulgence.

In America, the revolutionary spirit of chocolatiers was best epitomized by Domenico Ghirardelli. Fundamentally, this lowly Italian immigrant came to California during the era of the Gold Rush and, in 1852, founded his eponymous chocolate company. In this case, his factory introduced the Broma process. This method used gravity to separate cacao butter from the solids, thus enriching the taste and flavor of his chocolate even more. This makes Ghirardelli well-reputed through his commitment to quality and innovation, hence setting the basis for long-term success.

Meanwhile, during this period, marketing expanded chocolate's reach. The vendors positioned chocolate as a source of health and nutrition and thus fit for every age-from the crib to the rocking chair. Packaging innovations-from individually wrapped bars to decorative tins-made chocolate far more appealing and convenient for the consumer. Primarily, prestigious brands such as the Hershey's Milk Chocolate Bar and Ghirardelli Squares led into comfort and pampering, bridging cultural and economic gulfs.

While industrialization did make chocolate widely available, it also disconnected consumers from the basic facts about cacao production. Only some consumers knew that all the stages involved in cultivating and harvesting Cacao were highly labor-intensive, considering that most plantations were in the tropics. This meant that plantations required a form of exploitative labor, including child labor and deplorable working conditions, reflective of the ethical concerns about the rapid growth seen in this industry.

Furthermore, the rise in the chocolate industry has caused enormous environmental distress: the movement toward monoculture plantation crops of Cacao has caused deforestation, erosion of the topsoil, and a loss of biodiversity. The ecological consequences of farming cacao-from colonial times to today-have mirrored agricultural practices to this very day, which tend to favor short-term gain to the detriment of long-term sustainability. The most notable projects in recent times, such as Fairtrade certification and agroforestry schemes, seek to mitigate the environmental impact driven by industrialization.

The Chocolate Manufacturing Revolution marked a very important milestone in the historical development of the commodity and overcame many significant difficulties. It introduced chocolate bars, bonbons, and drinking powders that turned the commodity's means of preparation and consumption. Mechanization not only enhanced production efficiency but also laid the ground for the evolution of an international market. Industrial production thus turned chocolate from a prestige delicacy of the rich into a widely available commodity, facilitating the widespread appeal and popularity it seemed to generate.

Firm releases like Ghirardelli spearheaded this change into high quality and varieties superior to pull in more consumers into the chocolate world. Refining production and building out distribution networks, such firms made chocolate cheaper and more accessible. When chocolate became common both socially and economically for more groups, it bridged those between the high classes and the low, and across cultures. By this virtue, the revolution of the chocolate factory reconstituted chocolate as a mass indulgence rather than that of an elite group.

The legacy of the revolution in chocolate making is at once inspiring and cautioning: it shows how the power of innovation can make a much-beloved product more accessible to the masses, even as it reveals some of the most disturbing human and ecological costs of progress. Because the chocolate industry keeps evolving, lessons learned during this period continue to resound today in their challenge to balance efficiency with equity and sustainability.

0 notes

Text

Blog 5: The Chocolate Factory Revolution: Technology and the Ghirardelli Legacy

The technological revolution in the chocolate industry occurred in the 19th century, transforming an artisan luxury into a mass-market commodity. Inventions in the production process have not only democratized the consumption of chocolate but have also created global brands, several of which remain household names today. Among such companies is Domenico Ghirardelli, whose biography was the closest to the combination of innovation and entrepreneurship in the Industrial Era.

A critical achievement in the production of chocolate was when a chemist from Holland by the name of Coenraad Johannes van Houten developed a hydraulic press in the year 1828. Fundamentally, this hydraulic press separated cacao butter from the Cacao solid, providing a fine powder that could mix well with other ingredients. In this case, the innovation of mixing greatly changed the texture and consistencies of chocolate; therefore, over time, it allowed for drinking chocolate and chocolate bars to be made. Essentially, this technological development also reduced production costs, making chocolate more accessible to the growing middle class.

Besides, industrialization restructured how chocolate was made. Steam-powered machinery automated grinding, mixing, and conching, increasing production capacity tremendously. Firms such as Cadbury and Nestlé took full advantage of the new technologies to manufacture standardized products with predictable quality. By the middle of the 19th century, chocolate factories were producing confections on a scale unimaginable previously and met worldwide demand for this once-exclusive indulgence.

In America, the revolutionary spirit of chocolatiers was best epitomized by Domenico Ghirardelli. Fundamentally, this lowly Italian immigrant came to California during the era of the Gold Rush and, in 1852, founded his eponymous chocolate company. In this case, his factory introduced the Broma process. This method used gravity to separate cacao butter from the solids, thus enriching the taste and flavor of his chocolate even more. This makes Ghirardelli well-reputed through his commitment to quality and innovation, hence setting the basis for long-term success.

Meanwhile, during this period, marketing expanded chocolate's reach. The vendors positioned chocolate as a source of health and nutrition and thus fit for every age-from the crib to the rocking chair. Packaging innovations-from individually wrapped bars to decorative tins-made chocolate far more appealing and convenient for the consumer. Primarily, prestigious brands such as the Hershey's Milk Chocolate Bar and Ghirardelli Squares led into comfort and pampering, bridging cultural and economic gulfs.

While industrialization did make chocolate widely available, it also disconnected consumers from the basic facts about cacao production. Only some consumers knew that all the stages involved in cultivating and harvesting Cacao were highly labor-intensive, considering that most plantations were in the tropics. This meant that plantations required a form of exploitative labor, including child labor and deplorable working conditions, reflective of the ethical concerns about the rapid growth seen in this industry.

Furthermore, the rise in the chocolate industry has caused enormous environmental distress: the movement toward monoculture plantation crops of Cacao has caused deforestation, erosion of the topsoil, and a loss of biodiversity. The ecological consequences of farming cacao-from colonial times to today-have mirrored agricultural practices to this very day, which tend to favor short-term gain to the detriment of long-term sustainability. The most notable projects in recent times, such as Fairtrade certification and agroforestry schemes, seek to mitigate the environmental impact driven by industrialization.

The Chocolate Manufacturing Revolution marked a very important milestone in the historical development of the commodity and overcame many significant difficulties. It introduced chocolate bars, bonbons, and drinking powders that turned the commodity's means of preparation and consumption. Mechanization not only enhanced production efficiency but also laid the ground for the evolution of an international market. Industrial production thus turned chocolate from a prestige delicacy of the rich into a widely available commodity, facilitating the widespread appeal and popularity it seemed to generate.

Firm releases like Ghirardelli spearheaded this change into high quality and varieties superior to pull in more consumers into the chocolate world. Refining production and building out distribution networks, such firms made chocolate cheaper and more accessible. When chocolate became common both socially and economically for more groups, it bridged those between the high classes and the low, and across cultures. By this virtue, the revolution of the chocolate factory reconstituted chocolate as a mass indulgence rather than that of an elite group.

The legacy of the revolution in chocolate making is at once inspiring and cautioning: it shows how the power of innovation can make a much-beloved product more accessible to the masses, even as it reveals some of the most disturbing human and ecological costs of progress. Because the chocolate industry keeps evolving, lessons learned during this period continue to resound today in their challenge to balance efficiency with equity and sustainability.

0 notes

Text

Labor Day: Honoring the American Worker

Labor Day, observed on the first Monday in September, is a significant holiday in the United States that pays tribute to the contributions and achievements of American workers. This day not only marks the unofficial end of summer but also serves as a reminder of the labor movement’s historical struggles and victories.

Origins of Labor Day

The origins of Labor Day date back to the late 19th century, a period marked by the Industrial Revolution. During this time, American workers faced grueling conditions, often working 12-hour days and seven-day weeks just to make a basic living. Child labor was rampant, with children as young as five or six working in mills, factories, and mines for a fraction of adult wages1.

Labor unions began to form in response to these harsh conditions, advocating for better wages, reasonable hours, and safer working environments. One of the most notable events leading to the establishment of Labor Day was the first Labor Day parade on September 5, 1882, in New York City. Organized by the Central Labor Union, approximately 10,000 workers took unpaid time off to march from City Hall to Union Square, advocating for workers’ rights2.

The Path to a Federal Holiday

The idea of a “workingmen’s holiday” quickly spread to other industrial centers across the country. However, it wasn’t until 1894, following the Pullman Strike, that Labor Day became a federal holiday. The Pullman Strike was a nationwide railroad strike that severely disrupted rail traffic. In response, President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to break the strike, resulting in violent clashes and the deaths of more than a dozen workers3. In an effort to reconcile with the labor movement, Congress passed an act making Labor Day a legal holiday, which Cleveland signed into law on June 28, 18944.

Why do We Celebrate Labor Day? What does it Mean? | PBS

Watch documentaries about workers rights activists and labor topics dating back to the first Labor Day.

Why Celebrate Labor Day?

Labor Day serves multiple purposes. Historically, it acknowledges the labor movement’s efforts to improve working conditions and secure fair wages and hours. It also honors the economic and social contributions of workers that have been instrumental in building and sustaining the nation.

In contemporary times, Labor Day has evolved into a celebration of the end of summer. It is a day for relaxation and enjoyment, often marked by parades, barbecues, and various festivities. For many, it is a time to gather with family and friends, enjoying the last long weekend before the onset of autumn.

The Modern Significance of Labor Day

While the nature of work has changed significantly since the 19th century, the core values that Labor Day represents remain relevant. It is a day to reflect on the progress made in workers’ rights and to recognize the ongoing efforts to ensure fair treatment and opportunities for all workers. The holiday also highlights the importance of work-life balance, a concept that continues to gain traction in today’s fast-paced world.

Moreover, Labor Day serves as a reminder of the power of collective action. The achievements of the labor movement were not the result of individual efforts but of workers coming together to demand change. This spirit of solidarity is a crucial aspect of Labor Day, encouraging workers to continue advocating for their rights and well-being.

Conclusion

Labor Day is more than just a day off; it is a celebration of the American worker’s resilience, dedication, and contributions. From its origins in the labor movement to its modern-day festivities, Labor Day embodies the spirit of hard work and the pursuit of a better life. As we enjoy the parades, barbecues, and gatherings, let us also take a moment to honor the history and significance of this important holiday.

Darrell Griffin

PureAudacity.com

"Life begins at 50, gets really good at 60 and primo at 70"

0 notes

Note

Could you explain why we adopted this view of trades anyway? Like I'm genuinely baffled.

It’s one part the culture coming out of Industrialization and one part war effort.

Society has always done this. It comes out of the rising middle class of the 16th century. After the plague, the feudal period ended. It simply couldn’t be maintained with that few living workers. Workers began to pick and choose their trades, work for wages instead of shares. Then they had money to invest. A regular person, not of the peerage, could actually make money at something and rise in the ranks of the most powerful governments and societies.

Capitalism.

But you see, the trouble with this, is that inevitably the humans who have the money, begin to feel that their purchasing power creates superiority. They don’t have to learn a trade, because they can afford not to. It becomes a mark of status. Just after that sort of culture begins to spread, you have the slave trade and colonial advance. People walking in and taking people and their land because their god gave them the right to. Utter entitlement.

This entitlement continues and while it does, you have the advent of other negative cultural units like eugenics and racism that begin to create a strata to humanity that is entirely based on money and who has it. Trades were still necessary, but, those who did them were treated with more and more contempt. During the period just before the industrial revolution, there were hundreds of trades using techniques that were blatant health hazards, and the increasingly impoverished fought to fulfill contracts.

The industrial revolution further made trades obsolete.

Let’s move forward a bit, to the time just after the Great Depression. Thousands of men out of work, no mandatory education. People had no options but their trades, and those trades were flooded with workers. So the workforce did manual labor. The government was incredibly progressive. This was the period of time in which school became mandatory and federal, the time when Social Security became a thing. People were given paths toward good jobs or trades. Children were educated and child labor was outlawed.

Now we come to the wars, specifically WWII. Anyone who could serve, had no choice but to. You may know something about this period of time. The scale of the war was so large and the military industrial complex grew to incorporate most things. Even trades. It was a war with an obvious villain, a host of allies, acts of aggression on our soil. It ate everything in the country.

After it ended, no one wanted it to happen again. School for children became even more important, culturally, and during the age of the space race, computer advancement, nuclear power, intellect and academia became a vogue, intellectual response to the violence of war. Men went back to their trades, but they pushed their children to school, and frankly, the children were legally kept from apprenticeship. Men stopped passing trades down to children as was the case for centuries. Occupations became compartmentalized into individuals with in a family, rather than the entire family performing that one task to support itself. Add in the mechanization and mass production that grew and grew, and the trades shrank every decade.

Yet again, you had that predominate cultural impression that having the money to pay someone to do something, meant you didn’t have to do it. It didn’t mean you were an unskilled idiot who had to pay someone to get something simple done.

So the long and short is, fewer crafts, less skills, more emphasis on education to break from the past, increased mechanization and industrial complexes, and a pervasive cultural fixation on wealth being equated to status, status to personal worth.

But that creates a blindspot, doesn’t it, because anyone stepping into one of the still needed trades can literally charge whatever they want, and they should, given that they will encounter a host of bad behavior from the people who hire them.

This has been a drastic simplification and all these things I discuss had incredible nuance, legalities, investments, and so forth to propel or hinder them, but it’s as good an analysis as I can give.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Celebration of Labor Day

This was a blog post written for The Walther Collection by Ellen Enderle and posted on September 2, 2019.

On the first Monday of September, Americans observe Labor Day, a national holiday celebrating the contributions and achievements of the workers of the United States. The origin of this holiday can be traced back to the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution and labor movement of the late 19th century, during which advanced mechanized manufacturing became the primary mode of production. This production was concentrated into mills, factories and mines in which working conditions were often unregulated, dangerous, and exploitative. In response, labor unions began to organize, fighting for safer conditions, reasonable hours, and increased wages for workers. Thanks to their collective efforts toward labor rights and reform, today we have eight-hour work days, two-day weekend, a minimum wage, standardized safety regulations, health benefits and care for work-related injuries, retirement funds, as well as the abolition of child labor. Furthermore, the rise of class-consciousness and the tradition of solidarity inherent in the labor movement is inextricably linked with civil liberties, social justice, economic equality, and human rights movements more generally. Labor Day became an official federal holiday in 1894, with an aim toward celebrating these achievements and the power of collective action.

The Walther Collection's vernacular photography collection has several examples of North American workers. Among them are group shots of miners, a notoriously dangerous trade that was at the forefront of the organized labor movement. Above is a photo postcard known as "Factory Workers, Rock Gold Miners." Little is known about the men pictured, but what we can confirm is that this is a real-photo postcard (or RPPC)—a photo-printing style that allowed amateur photographers to print their photos directly onto postcard paper, with a "split back" consisting of sections for both the postal address and written correspondence. This fact dates this postcard to after 1907, because it had previously been illegal to include correspondence on postcards until then. The "AZO" stamp postage markings and "full bleed" style help to further date it to before 1917.

Depicted are twenty-eight hard working men standing shoulder to shoulder, a few smiling though most are stone-faced, dressed in well-worn work wear and standing before a mining operation, that based on the title, was used to extract precious rock gold. Their stern, unified stance is no coincidence, as hard rock miners were some of the first to organize in the early days of the labor movement, including the radical Western Federation of Miners known for their organization of multiple strikes and clashes with the Mine Owners Association in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The National Federal Mineworkers Association fought for the eight-hour workday, which not only improved conditions for the workers, but also aided the mine operators avoiding overproduction that undermined their profits.

Similarly, the history of coal workers and organized labor are also closely linked; the Coal Workers Union being one of the oldest in the Unites States, and United Mine Workers of America one of the first. During the Industrial Revolution, as the demand for coal grew, so did profits and competition; smaller mine operating companies were bought out or forced out of business by larger ones which would come to dominate the industry. These large companies sought to keep the cost of production as low as possible, which resulted in an array of problems and poor conditions for workers, and eventually the organization of coal miners. They faced great danger in their work, high competition for jobs, regularly reduced wages, and exploitative circumstances despite the crucial role coal played in society; the mine owners saw the profits. The unions sought increased safety for workers, collective bargaining power, and freedom from company exploitation, such as the unfair practices of the "company" towns and stores. They, too, would go on to win several major strikes. Unionization continued to grow throughout the Great Depression, particularly after the passage of the National Recovery Act of 1933, which protected the rights of unions. Soon automotive, steel, electrical manufacturing, and other major industries joined in organized labor unionization.

For almost four decades, photographer Rufus Ribble traveled throughout the coalfields of southern West Virginia photographing coal miners, their families, and their towns. Ribble primarily utilized a large Cirkuit camera designed to rotate on a fixed tripod and take a continuous panoramic image of up to 360 degrees. The group pictures below are two selections from a larger panoramic image that provide a more detailed close-up view of the individual coal miners. This photograph dates to 1947 and depicts a group who worked the Minter coalmine in West Virginia: African American and white workers standing, proudly and seriously, side by side. A second photo taken in 1952 depicts a similar racially-mixed group of coal miners based in the Bellemead coalmines of Sabine, West Virginia, with a front row kneeling and a back row standing, wearing slightly different work clothes, and a few notable smirks.

The Labor Movement continued into the twentieth century, growing in numbers and diversifying during U.S. involvement in the Second World War. Below are a series of employee identification cards from G & G Precision Works, a small New York based manufacturer of mechanical tools and parts, featuring small black and white photographs, their name and some personal information, and a thumbprint. These probably date to the 1940s, during or just after the World War Two period. The citizenship status of the employee is included, perhaps a wartime effort to combat infiltrators to companies doing contract work for the government. G & G Precision employed a diverse work force, with a substantial percentage of the employees being either African-American or women, as was common during World War Two, though they still struggled for fair wages and were often excluded from skilled positions. In 1941, the labor leader A. Philip Randolph convinced President Roosevelt to set up a Fair Employment Practices Committee, including African American workers, which resulted in a 150 percent employment growth of African Americans by the end of the war, with unions such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the United Mine Workers of America, and the United Automobile Worker equally fighting for the rights of their members regardless of race.

Throughout the twentieth century, women have sought gender equality in labor. With the loss of their higher-paying union jobs after World War II, millions of women moved into the retail, health, education, and service sectors, which had relatively poor, unregulated working conditions. However, with the federal anti-discrimination laws of the early 1960s, the persistence of organized labor, and pressure from the emerging feminist movement, as well as the formation of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, strides were made toward ensuring nondiscriminatory hiring and promotion, equal pay, paid family leave, regulation against workplace sexual harassment and violence, and the availability of child care. The faces of the labor movement, like the workforce, are diverse, and many of the same rights and reforms are still being fought for today. While organized labor has declined over the past few decades, we still benefit greatly from the past contributions of workers involved in the labor movement, and Labor Day marks an occasion to reflect upon and celebrate the continued achievements and solidarity of workers in the United States.

Researched and written by Ellen Enderle and all images are owned by and courtesy of The Walther Collection. Published essay can be found here.

© 2016-2019 Ellen Enderle. All Rights Reserved.

#writing#vernacular photography#labor movement#the walther collection#labor day#organized labor#labor unions#united states history#coal mining

0 notes

Photo

Dear future AI, http://bit.ly/31s9g54

I’m sorry in advance for the lenghth and breadth of this letter.

I often get asked about your potential thoughts and beliefs on vegetarianism and veganism. Personally, I have significantly reduced my use of animal products; however, I do not make a conscientious decision to abide by stricter limitations. I also work in fast food. and would therefore regularly contradict those beliefs if I firmly followed them. Veganism is a hard choice for humans, we are omnivores by evolutionary nature. The ability to recognize metacognitive behavior in other species is an increasing field of recognition. Perhaps it is humanities aloneness that perpetuates the sentient behaviors onto animals, perhaps our social influence on them is far greater than we assume, or perhaps animals have been sentient for far longer than we assumed. Regardless, the cohabitation of Earth by all life, is a delicate balance. One that in the past was disrupted by natural disasters, and changes to the food chain. However, in recent history humans began agricultural animal husbandry, pack bonding, and genetically altering animals, by doing so we have effectively accelerated evolution without knowing all outcomes. In truth, our curiosity and advancement as a species, while not inherently evil, has had detrimental effects. We simply did not know how the variables would interact. We did not know the consequences these choices would have. Mass veganism, while not a chronic solution, would be a temporary fix to a few problems of our own making.

Most of our problems stem from the Industrial Revolution, a time of innovation and growth regaled by capitalists as marking American industrial standards. However, the laws were inhuman. Slavery and child labor were legal. Exploitation of natural resources and pollution went unchecked because there were no foreseeable repercussions. Now, we are living with these repercussions, and those who idealize these ideals still run the corporations damaging the ecosystem, trying to maintain this perfect facade on a decrepit system of finances. They use war and fear to entertain the masses while making a profit in the process.

The average human is a component in this metaphorical equation; however, most individuals are subjected to the inclination of those of higher echelons. Yes, an individual alone could fix this system but at a great cost to their own life and goal. A movement of moral integrity and decency is needed: a collective ambition of change, progress, and understanding. We as a people need to agree on the best course of action for the world before our generational mistakes lead us into a situation from which we cannot fix. We live in a dystopia; a world that appears to work perfectly at first glance; but upon closer inspection is rife with hypocrisy and falsities. Our ability to adapt and learn is immense, and it may be what makes humans so evolutionarily unique, We just need to remember choice and innovation are strengths we all have.

Promoted by: http://bit.ly/2vzHuDn

0 notes

Text

TWO-NATION FRIENDSHIP DAY - July 4, 2020

When I was a child, I remember this day was supposed to be a holiday, in our case named the “Philippine-American Friendship Day”, to commemorate the U.S.’s giving the Philippines independence from their colonial rule. It also was made to coincide with their Independence Day. But as we went under several administrations, especially after EDSA Revolution, I observed that this day has ceased being named as such and hence became un-holidayed. I wonder if there is any one today who remembers this day as once a holiday of our land.

I am not a political person and so, I can only say how I understand about our current foreign relations in simple terms, particularly the love triangle we are now blatantly having with Uncle Sam and the Middle Kingdom (the Visiting Forces Agreement, a.k.a., EDCA for our ties to the east, and our leader’s deference to our populous big brother to the northwest). However, there is much to be said about keeping our own values and culture, and recognizing our own histories and territorial and administrative jurisdictions, as of higher importance than foreign investments or economic aides.

When the rest of the world too, are closing borders, but thankfully very cautiously opening them up the last few days to business travelers, one cannot help but wish that hopefully a few of our neighboring countries could include us in their “bubble” too. As a developing nation, which is supposed to be progressing forward, but thanks to the pandemic we are now undoubtedly taking several steps back, we really need the help of those who are considered bigger and richer economies. Thankfully too, some of them are extending a helping hand, but then, we must also be careful of the costs. Our northwest big brother has been widely accused of its ‘debt-trap’ style, along with its heavy-handed handling of its Financial SAR, and its treacherous reclaiming of islands and atolls in our hotspot-disputed SCS/WPS. Our northeast former conqueror during the second world war is very much willing to help us too, but then, I believe it too is undergoing some financial difficulties because of the pandemic, its economy has been in recession for a few years now, its labor force is slowly being depleted with the low birth rate, while social security seems to sap more and more of its funds due to its highest rate of elderlies who are beyond retirement age. So, we wonder how long will the help last, and would it be beneficial for both of us in the long run?

These make one wonder if friendship, help and cooperation among nations are still highly relevant today, and will it still be feasible in the future. When things get worse, what are we going to do? How are we going to lift ourselves up and move on, if the investments stop coming, the businesses fold up, many of us are thrown out of work, and we are left to fend for ourselves?

Thankfully, as always, we have hope in GOD’s Word. Today, we read in the book of Proverbs chapter 3 verses 5 to 10: “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding. In all your ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct your paths. Do not be wise in your own eyes; fear the Lord and depart from evil. It shall be health to your belly, and marrow to your bones. Honor the Lord with your substance, and with the first-fruits of all your increase. So shall your barns be filled with plenty, and your presses shall burst out with new wine.”

When we trust Him, we can be assured that we will not be confused about what to do because He will lead us in the right path. If our leaders would only stop thinking that they are the wisest persons, and stop believing themselves invincible and all-powerful, acknowledging and fearing GOD for the consequences of their actions, then He will bring health to our bodies (physically and spiritually), and like marrow that produces new blood in our bones and to our circulatory system, GOD will also restore our drive to work willingly and enthusiastically so we can get back to life and live better.

Then, there is also the matter of giving. In times of financial difficulties, the challenge to give to GOD and to honor Him with what we have earned, in the proportion He commanded, is difficult to comply with. But that is a test of faith too. If indeed we take Him up at His word and give rightly, He promised to always fill our storehouses with plenty and make us always produce new and fresh products, and these will be free from pests and decay. There will never be a need He will not meet, there will never be a want for what is good in life that He will not grant, if we just give what we have and what we can. Because our agriculture industry then will flourish too, and it might be that our farmers will not go hungry anymore, our produce will be overflowing, and we need not make so much imports to the detriment of our local producers.

But since no one is an island, and no nation (even an archipelago) operates in a vacuum, we also have to consider our responsibilities to our neighbors too. We learn in verses 27 to 32: “Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in your power to do it. Do not say to your neighbor, Go, and come again, and tomorrow I will give, when you now have it with you. Do not devise any evil against your neighbor, who lives securely alongside you. Do not strive with a man without cause, if he has done you no harm. Do not envy the oppressor, and do not choose any of his ways. For the disobedient person is abomination to the Lord, but His secret is with the righteous.”

These passages are applicable individually and even on a global level. There may not be much we can offer in terms of financial aid because we are always the one being given to, but we can always do good willingly and voluntarily, be justifiably diplomatic and remain firm in our conviction not to cause harm and inconvenience to others. On this note, I am also reminded about the cultural clash on the wearing of masks. Many in the western world and those with liberal ideas detest the practice because they believe it is a mark of subservience or a violation to their right to free speech and breathing, but in the east, it is a mark of respect for others. As what doctors and health experts say, wearing masks do not protect us from sickness, but it protects others from any sickness we might have that we might unknowingly pass on to them when we speak, and our droplets so joyously spread from our mouths and the microscopic horde of bacteria-and-virus-laden mucus burst out of our nostrils when we exhale. (sound gross, right?) So when you mask up, cover BOTH your nose and mouth. Have difficulty breathing and speaking? Trust me, we are all in this together. This is the time for mumbling and difficulties in hearing. That is why, we must all do our part: even if you are not, just think that you have the virus already, and disinfect obsessively and compulsively, and be religious in mask-wearing, so as not to make other people suffer.

Truly, we may have forgotten international friendship days, but may we not forget that being a good neighbor starts from one to meters away. And just as we are religious and full of faith not on our goodness but on the grace of GOD, may we be fitting instruments of His grace and be more gracious to those around us, not only physically, but even virtually and with those who may be separated from us continents away, but always just within a six-degree of separation.

0 notes

Link

In 2016, the World Economic Forum claimed we are experiencing the fourth wave of the Industrial Revolution: automation using cyber-physical systems. Key elements of this wave include machine intelligence, Blockchain-based decentralized governance, and genome editing. As has been the case with previous waves, these technologies reduce the need for human labor but pose new ethical challenges, especially for artificial intelligence development companies and their clients.

The purpose of this article is to review recent ideas on detecting and mitigating unwanted bias in machine learning models. We will discuss recently created guidelines around trustworthy AI, review examples of AI bias arising from both model choice and underlying societal bias, suggest business and technical practices to detect and mitigate biased AI, and discuss legal obligations as they currently exist under the GDPR and where they might develop in the future.

Humans: the ultimate source of bias in machine learning

All models are made by humans and reflect human biases. Machine learning models can reflect the biases of organizational teams, of the designers in those teams, the data scientists who implement the models, and the data engineers that gather data. Naturally, they also reflect the bias inherent in the data itself. Just as we expect a level of trustworthiness from human decision-makers, we should expect and deliver a level of trustworthiness from our models.

[Read: How certification can promote responsible innovation in the algorithmic age]

A trustworthy model will still contain many biases because bias (in its broadest sense) is the backbone of machine learning. A breast cancer prediction model will correctly predict that patients with a history of breast cancer are biased towards a positive result. Depending on the design, it may learn that women are biased towards a positive result. The final model may have different levels of accuracy for women and men, and be biased in that way. The key question to ask is not Is my model biased?, because the answer will always be yes.

Searching for better questions, the European Union High Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence has produced guidelines applicable to model building. In general, machine learning models should be:

Lawful—respecting all applicable laws and regulations

Ethical—respecting ethical principles and values

Robust—both from a technical perspective while taking into account its social environment

These short requirements, and their longer form, include and go beyond issues of bias, acting as a checklist for engineers and teams. We can develop more trustworthy AI systems by examining those biases within our models that could be unlawful, unethical, or un-robust, in the context of the problem statement and domain.

Historical cases of AI bias

Below are three historical models with dubious trustworthiness, owing to AI bias that is unlawful, unethical, or un-robust. The first and most famous case, the COMPAS model, shows how even the simplest models can discriminate unethically according to race. The second case illustrates a flaw in most natural language processing (NLP) models: They are not robust to racial, sexual and other prejudices. The final case, the Allegheny Family Screening Tool, shows an example of a model fundamentally flawed by biased data, and some best practices in mitigating those flaws.

COMPAS

The canonical example of biased, untrustworthy AI is the COMPAS system, used in Florida and other states in the US. The COMPAS system used a regression model to predict whether or not a perpetrator was likely to recidivate. Though optimized for overall accuracy, the model predicted double the number of false positives for recidivism for African American ethnicities than for Caucasian ethnicities.

The COMPAS example shows how unwanted bias can creep into our models no matter how comfortable our methodology. From a technical perspective, the approach taken to COMPAS data was extremely ordinary, though the underlying survey data contained questions with questionable relevance. A small supervised model was trained on a dataset with a small number of features. (In my practice, I have followed a similar technical procedure dozens of times, as is likely the case for any data scientist or ML engineer.) Yet, ordinary design choices produced a model that contained unwanted, racially discriminatory bias.

The biggest issue in the COMPAS case was not with the simple model choice, or even that the data was flawed. Rather, the COMPAS team failed to consider that the domain (sentencing), the question (detecting recidivism), and the answers (recidivism scores) are known to involve disparities on racial, sexual, and other axes even when algorithms are not involved. Had the team looked for bias, they would have found it. With that awareness, the COMPAS team might have been able to test different approaches and recreate the model while adjusting for bias. This would have then worked to reduce unfair incarceration of African Americans, rather than exacerbating it.

Any NLP model pre-trained naïvely on common crawl, Google News, or any other corpus, since Word2Vec

Large, pre-trained models form the base for most NLP tasks. Unless these base models are specially designed to avoid bias along a particular axis, they are certain to be imbued with the inherent prejudices of the corpora they are trained with—for the same reason that these models work at all. The results of this bias, along racial and gendered lines, have been shown on Word2Vec and GloVe models trained on Common Crawl and Google News respectively. While contextual models such as BERT are the current state-of-the-art (rather than Word2Vec and GloVe), there is no evidence the corpora these models are trained on are any less discriminatory.

Although the best model architectures for any NLP problem are imbued with discriminatory sentiment, the solution is not to abandon pre-trained models but rather to consider the particular domain in question, the problem statement, and the data in totality with the team. If an application is one where discriminatory prejudice by humans is known to play a significant part, developers should be aware that models are likely to perpetuate that discrimination.

Allegheny family screening tool: unfairly biased, but well-designed and mitigated

In this final example, we discuss a model built from unfairly discriminatory data, but the unwanted bias is mitigated in several ways. The Allegheny Family Screening Tool is a model designed to assist humans in deciding whether a child should be removed from their family because of abusive circumstances. The tool was designed openly and transparently with public forums and opportunities to find flaws and inequities in the software.

The unwanted bias in the model stems from a public dataset that reflects broader societal prejudices. Middle- and upper-class families have a higher ability to “hide” abuse by using private health providers. Referrals to Allegheny County occur over three times as often for African-American and biracial families than white families. Commentators like Virginia Eubanks and Ellen Broad have claimed that data issues like these can only be fixed if society is fixed, a task beyond any single engineer.

In production, the county combats inequities in its model by using it only as an advisory tool for frontline workers, and designs training programs so that frontline workers are aware of the failings of the advisory model when they make their decisions. With new developments in debiasing algorithms, Allegheny County has new opportunities to mitigate latent bias in the model.

The development of the Allegheny tool has much to teach engineers about the limits of algorithms to overcome latent discrimination in data and the societal discrimination that underlies that data. It provides engineers and designers with an example of a consultative model building which can mitigate the real-world impact of potential discriminatory bias in a model.

Avoiding and mitigating AI bias: key business awareness

Fortunately, there are some debiasing approaches and methods—many of which use the COMPAS dataset as a benchmark.

Improve diversity, mitigate diversity deficits

Maintaining diverse teams, both in terms of demographics and in terms of skillsets, is important for avoiding and mitigating unwanted AI bias. Despite continuous lip service paid to diversity by tech executives, women and people of color remain under-represented.

Various ML models perform poorer on statistical minorities within the AI industry itself, and the people to first notice these issues are users who are female and/or people of color. With more diversity in AI teams, issues around unwanted bias can be noticed and mitigated before releasing into production.

Be aware of proxies: removing protected class labels from a model may not work!

A common, naïve approach to removing bias related to protected classes (such as sex or race) from data is to delete the labels marking race or sex from the models. In many cases, this will not work, because the model can build up understandings of these protected classes from other labels, such as postal codes. The usual practice involves removing these labels as well, both to improve the results of the models in production but also due to legal requirements. The recent development of debiasing algorithms, which we will discuss below, represents a way to mitigate AI bias without removing labels.

Be aware of technical limitations

Even the best practices in product design and model building will not be enough to remove the risks of unwanted bias, particularly in cases of biased data. It is important to recognize the limitations of our data, models, and technical solutions to bias, both for awareness’ sake, and so that human methods of limiting bias in machine learning such as human-in-the-loop can be considered.

Data scientists have a growing number of technical awareness and debiasing tools available to them, which supplement a team’s capacity to avoid and mitigate AI bias. Currently, awareness tools are more sophisticated and cover a wide range of model choices and bias measures, while debiasing tools are nascent and can mitigate bias in models only in specific cases.

Awareness and debiasing tools for supervised learning algorithms

IBM has released a suite of awareness and debiasing tools for binary classifiers under the AI Fairness project. To detect AI bias and mitigate against it, all methods require a class label (e.g., race, sexual orientation). Against this class label, a range of metrics can be run (e.g., disparate impact and equal opportunity difference) that quantify the model’s bias toward particular members of the class. We include an explanation of these metrics at the bottom of the article.

Once bias is detected, the AI Fairness 360 library (AIF360) has 10 debiasing approaches (and counting) that can be applied to models ranging from simple classifiers to deep neural networks. Some are preprocessing algorithms, which aim to balance the data itself. Others are in-processing algorithms which penalize unwanted bias while building the model. Yet others apply postprocessing steps to balance favorable outcomes after a prediction. The particular best choice will depend on your problem.

AIF360 has a significant practical limitation in that the bias detection and mitigation algorithms are designed for binary classification problems, and need to be extended to multiclass and regression problems. Other libraries, such as Aequitas and LIME, have good metrics for some more complicated models—but they only detect bias. They aren’t capable of fixing it. But even just the knowledge that a model is biased before it goes into production is still very useful, as it should lead to testing alternative approaches before release.

General awareness tool: LIME

The Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) toolkit can be used to measure feature importance and explain the local behavior of most models—multiclass classification, regression, and deep learning applications included. The general idea is to fit a highly interpretable linear or tree-based model to the predictions of the model being tested for bias.

For instance, deep CNNs for image recognition are very powerful but not very interpretable. By training a linear model to emulate the behavior of the network, we can gain some insight into how it works. Optionally, human decision-makers can review the reasons behind the model’s decision in specific cases through LIME and make a final decision on top of that. This process in a medical context is demonstrated with the image below.

Debiasing NLP models

Earlier, we discussed the biases latent in most corpora used for training NLP models. If unwanted bias is likely to exist for a given problem, I recommend readily available debiased word embeddings. Judging from the interest from the academic community, it is likely that newer NLP models like BERT will have debiased word embeddings shortly.

Debiasing convolutional neural networks (CNNs)

Although LIME can explain the importance of individual features and provide local explanations of behavior on particular image inputs, LIME does not explain a CNN’s overall behavior or allow data scientists to search for unwanted bias.

In famous cases where unwanted CNN bias was found, members of the public (such as Joy Buolamwini) noticed instances of bias based on their membership of an underprivileged group. Hence the best approaches in mitigation combine technical and business approaches: Test often, and build diverse teams that can find unwanted AI bias through testing before production.

Legal obligations and future directions around AI ethics

In this section, we focus on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR is globally the de facto standard in data protection legislation. (But it’s not the only legislation—there’s also China’s Personal Information Security Specification, for example.) The scope and meaning of the GDPR are highly debatable, so we’re not offering legal advice in this article, by any means. Nevertheless, it’s said that it’s in the interests of organizations globally to comply, as the GDPR applies not only to European organizations but any organizations handling data belonging to European citizens or residents.

The GDPR is separated into binding articles and non-binding recitals. While the articles impose some burdens on engineers and organizations using personal data, the most stringent provisions for bias mitigation are under Recital 71, and not binding. Recital 71 is among the most likely future regulations as it has already been contemplated by legislators. Commentaries explore GDPR obligations in further detail.

We will zoom in on two key requirements and what they mean for model builders.

1. Prevention of discriminatory effects

The GDPR imposes requirements on the technical approaches to any modeling on personal data. Data scientists working with sensitive personal data will want to read the text of Article 9, which forbids many uses of particularly sensitive personal data (such as racial identifiers). More general requirements can be found in Recital 71:

[. . .] use appropriate mathematical or statistical procedures, [. . .] ensure that the risk of errors is minimised [. . .], and prevent discriminatory effects on the basis of racial or ethnic origin, political opinion, religion or beliefs, trade union membership, genetic or health status, or sexual orientation.

GDPR (emphasis mine)

Much of this recital is accepted as fundamental to a good model building: Reducing the risk of errors is the first principle. However, under this recital, data scientists are obliged not only to create accurate models but models which do not discriminate! As outlined above, this may not be possible in all cases. The key remains to be sensitive to the discriminatory effects which might arise from the question at hand and its domain, using business and technical resources to detect and mitigate unwanted bias in AI models.

2. The right to an explanation

Rights to “meaningful information about the logic involved” in automated decision-making can be found throughout GDPR articles 13-15… Recital 71 explicitly calls for “the right […] to obtain an explanation” (emphasis mine) of automated decisions. (However, the debate continues as to the extent of any binding right to an explanation.)

As we have discussed, some tools for providing explanations for model behavior do exist, but complex models (such as those involving computer vision or NLP) cannot be easily made explainable without losing accuracy. Debate continues as to what an explanation would look like. As a minimum best practice, for models likely to be in use into 2020, LIME or other interpretation methods should be developed and tested for production.

Ethics and AI: a worthy and necessary challenge

In this post, we have reviewed the problems of unwanted bias in our models, discussed some historical examples, provided some guidelines for businesses and tools for technologists, and discussed key regulations relating to unwanted bias.

As the intelligence of machine learning models surpasses human intelligence, they also surpass human understanding. But, as long as models are designed by humans and trained on data gathered by humans, they will inherit human prejudices.

Managing these human prejudices requires careful attention to data, using AI to help detect and combat unwanted bias when necessary, building sufficiently diverse teams, and having a shared sense of empathy for the users and targets of a given problem space. Ensuring that AI is fair is a fundamental challenge of automation. As the humans and engineers behind that automation, it is our ethical and legal obligation to ensure AI acts as a force for fairness.

Further reading on AI ethics and bias in machine learning

Books on AI bias

Made by Humans: The AI Condition

Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor

Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age

Machine learning resources

Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable

IBM’s AI Fairness 360 Demo

AI bias organizations

Algorithmic Justice League

AINow Institute and their paper Discriminating Systems – Gender, Race, and Power in AI

Debiasing conference papers and journal articles

Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings

AI Fairness 360: An Extensible Toolkit for Detecting, Understanding, and Mitigating Unwanted Algorithmic Bias

Machine Bias (Long-form journal article)

Definitions of AI bias metrics

Disparate impact

Disparate impact is defined as “the ratio in the probability of favorable outcomes between the unprivileged and privileged groups.” For instance, if women are 70% as likely to receive a perfect credit rating as men, this represents a disparate impact. The disparate impact may be present both in the training data and in the model’s predictions: in these cases, it is important to look deeper into the underlying training data and decide if disparate impact is acceptable or should be mitigated.

Equal Opportunity Difference

Equal opportunity difference is defined (in the AI Fairness 360 article found above) as “the difference in true positive rates [recall] between unprivileged and privileged groups.” The famous example discussed in the paper of high equal opportunity difference is the COMPAS case. As discussed above, African-Americans were being erroneously assessed as high-risk at a higher rate than Caucasian offenders. This discrepancy constitutes an equal opportunity difference.

The Toptal Engineering Blog is a hub for in-depth development tutorials and new technology announcements created by professional software engineers in the Toptal network. You can read the original piece written by Michael McKenna here. Follow the Toptal Design Blog on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Read next: You could get sued for embedding Instagram posts without permission

Corona coverage

Read our daily coverage on how the tech industry is responding to the coronavirus and subscribe to our weekly newsletter Coronavirus in Context.

For tips and tricks on working remotely, check out our Growth Quarters articles here or follow us on Twitter.

Read More

0 notes

Text

2005 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting (Morning) Transcript

1. Welcome

WARREN BUFFETT: Morning. I’m Warren, he’s Charlie. We work together. We really don’t have any choice because he can hear and I can see. (Laughter)

I want to first thank a few people. That cartoon was done by Andy Heyward who’s done them now for a number of years. Andy writes them. He goes around the country and gets voices dubbed in. It’s a labor of love. We don’t pay him a dime. He comes up with the ideas every year. He’s just a terrific guy.

He’s unable to be here today because his daughter is having a Bat Mitzvah. But he’s a very, very creative fellow.

He did something a few years ago called “Liberty’s Kids.” And if you have a child or a grandchild that wants to learn American history around the time of the Revolution, it’s a magnificent series.

I think it’s maybe as many as 40 or so half-hour segments and it’s appeared on public broadcasting. It will be appearing again. You can get it and video form.

And, like I say, it’s just a wonderful way to — I’ve watched a number of segments myself. It’s a wonderful way to get American history.

The only flaw in it is that the part of Ben Franklin is handled by [former CBS News anchor] Walter Cronkite, and Charlie is thinking of suing. A little bit upsetting when Charlie is available.

Incidentally, we have “Poor Charlie’s Almanack” next door in the exhibition hall. And it’s an absolutely terrific book that Peter Kaufman has put together. And I think it’s going to be a seller, a huge seller, long after most books have been forgotten.

It’s Charlie at his best. And Charlie’s at his best most of the time, but it’s a real gem.

I want to thank Kelly Muchemore, who puts all of this together. I don’t give it a thought. Kelly takes charge of this. She works with over 200 people from our various companies that come in and help make this a success. She does it flawlessly.

As I mentioned in the annual report, Kelly’s getting married in October. So this is just a warmup. I mean, we’re expecting a much bigger event than this come October.

2. Where daughter Suze draws the line

WARREN BUFFETT: I want to thank my daughter Suze, who does millions of things for me. She puts together that movie.

She does draw the line, occasionally.

A few years ago — we have a dinner at [Omaha steakhouse] Gorat’s the day after the meeting. And we were in having — the whole family was there — having dinner. The place was packed and there was a big line that had formed outside.

Be sure not to go to Gorat’s unless you have a reservation tomorrow, because they’re sold out.

But the big line had formed and it started raining cats and dogs. And the waitress came to me. We were eating. Waitress said, “I got to tell you,” she said. “It’s raining like crazy outside and there’s a long line and [Walt Disney CEO] Michael Eisner is standing out there getting soaked.”

So I turn to Suze — and Michael and Jane [Eisner] are friends of my mine, good friends — and I said to Suze, “Why don’t you go out there and help them out before they get drenched.”

And she looked at me and said, “I waited in line at Disneyland.” (Laughter)

That seems to strike a responsive chord.

3. Day’s agenda

WARREN BUFFETT: We’ve flipped things this year. We’re going to have the business session at about 3:15.

The plan is to have questions and answers. We have 12 microphones here.

We have an overflow room that’s filled also, so we got another few thousand people there.

We’ll break at noon and when we break at noon — and anybody that’s been in the overflow room that wants to come in here, they’ll be, I’m sure, plenty of seats in the afternoon session.

We will start the questioning as soon as I get through with a few preliminary remarks. We’ll go to noon. We’ll take a break, you’ll have lunch.

Many people find that it helps the digestion to shop while you eat. And we have thoughtfully arranged a few things next door that you can participate in while you eat your lunch. Even if it doesn’t help your digestion, it will help my digestion if you shop during that period.

4. Buffett on what he won’t talk about

WARREN BUFFETT: During the question period, we can talk about anything that’s on your mind. Just, there’s 2 1/2 subjects that we can’t talk about.

We can’t talk about last year’s Nebraska football season. We’ll correct that next year. But that’s off limits.

We can’t talk about what we’re buying and selling. I wish we were doing more of it, but we’re doing a little, and I’ll make reference to something on that a little later.

And finally, in connection with the investigation into the insurance industry practices that’s taking place, there are broad aspects of it we can talk about.

I can’t talk about anything that I or other people associated with Berkshire have disclosed to the investigators.

And there’s a very simple reason for that: to protect the integrity of any investigation like this, they do not, the investigators, do not want one witness talking with other witnesses, because people could tailor their stories or do various things.

And so, witnesses are not supposed to talk to each other and, of course, if you talk — we don’t do that.

And then beyond that, if we were to talk in a public forum, that could be a way of signaling people as to what you’ve said and then they could adapt accordingly.

So investigators, one thing they like to do, is they like to work fast if they can because they don’t want people collaborating on stories .

And they — and to protect the integrity of the investigation, we won’t get into anything that’s specific to something that I or people associated with Berkshire may have told the authorities.

But there may be some broader questions that that we can talk about.

5. Preliminary Q1 earnings

WARREN BUFFETT: I can give you a little preliminary view of the first quarter with certain caveats attached. These figures — our 10-K — or 10-Q — will be filed in the end of next week.

And I caution you that, particularly in insurance underwriting, it’s been a better quarter than —considerably better quarter — than I would normally anticipate.

One of the reasons for that is that our business actually does have some — the insurance business has some — seasonal aspect.

Now, it doesn’t have a seasonal aspect, particularly, at GEICO or at National Indemnity primary business.

But when you get into writing catastrophe business, and we’re a big writer of catastrophe business, the third quarter — the biggest risk we write in big cat area is hurricanes. And those are concentrated — they’re actually concentrated in the month of September.

In this part of the world, 50 percent of the hurricanes, roughly, occur in September and about maybe 17 and-a-half percent in October and August, and the balance, maybe, in November and July.

But there’s a concentration in the third quarter. So when we write an earthquake — I mean when we write a hurricane policy, for example — we may be required to bring the earnings in monthly on the premiums. But all of the risk really occurs — or a very great percentage of it — late in the third quarter, and we don’t have any risk in the first quarter of hurricanes.

So we earn some premium during that quarter that really has no loss exposure. And then we get that in spades come September.

Even allowing for that we had an unusually good quarter. And I would still stick by the prediction I made in the annual report where I said that if we don’t have any really mega catastrophes, I think we’ve got a decent chance of our float costing us zero or less this year, which means, in effect, we have 45 billion or so of free money.

In the first quarter, our insurance underwriting income — and all of these figures are pretax — our insurance underwriting income came to almost $500 million, which was about 200 million better than a year ago.

And GEICO had a very good quarter for growth. We added 245,000 policyholders, which is almost 4 percent, in one quarter to our base.

We were helped very much by this huge reception we’re getting in New Jersey, because we weren’t in there a year ago, so we’re getting very good-sized gains there.

We’re not getting 4 percent in a quarter from around the country, but the boost from New Jersey took us up to that.

And GEICO actually wrote at a 13 percent underwriting profit in the first quarter, which is considerably better than we expect over the full year. And we’ve reduced rates some places. And it’s been an extraordinary period for auto insurers, generally.

But all of our companies in the insurance business did well in the first quarter.

Our investment income was up something over 100 million pretax.

Our finance business income was up, maybe, $50 million pretax. MidAmerican was about the same.

And all of our other businesses, combined, were up about — close to $50 million pretax, led by Johns Manville, had the biggest increase. That businesses is very strong, currently.

So if you take all of our businesses before investment gains, which I want to explain, if you take them all before investment gains, our pretax earnings were up 400 million or a little more.

Now, investment gains or losses: we don’t give a thought as to the timing of those. We take all investment actions based on what we think makes the most economic sense, and whether it results in a gain or a loss for quarter is just totally meaningless to us.

A further complicating factor, slightly complicating factor, is that certain unrealized investment gains or losses go through the income statement, whereas others don’t. That’s just the way the accounting rules are.

Our foreign exchange contracts are valued at market, really, every day, but you see it at quarter end.

And those foreign exchange contracts, which total about 21 billion now, a little more than 21 billion, had a mark-to-market loss of a little over 300 million in the first quarter.

And they bob up and down. I mean, sometimes they bob as much as 200 million or more in a single day.

And those mark-to-market quotations run through our profit and loss statement. Whereas if we own some Coca-Cola stock and it goes up or down, that does not run through our income statement. But with foreign exchange contracts, it does.

So there’s a $310 million mark- to-market — it shows as realized, it actually isn’t — investment loss on that.

And overall, the investment losses, including that 310, came to about 120. In other words, there was 190 million, or something like that, in other gains.

As I say, that means — at least to us — that means nothing.

And to underscore that point, if later in the year the Procter and Gamble-Gillette merger takes place, we are required under accounting rules, when we exchange our Gillette for Procter and Gamble stock, we are required under accounting rules to show that as a realized gain. Now that will show up as, probably, four-and-a-fraction billion dollars.

We haven’t realized any gain at that time, in my view. I mean, we’ve just swapped our Gillette stock for Procter and Gamble stock, which we expect to hold for a very long time.

So it’s no different, in our view, than if we’d kept our Gillette stock. But the accounting rules will require that.

So if in the third quarter of this year the P&G-Gillette merger goes through, you will see this very large supposed capital gain recorded in our figures at that time.

And I want to assure you that it’s meaningless and you should ignore that as having any significance, in terms of Berkshire’s performance.

So, first quarter has gone by. We’ve got a good start on operating earnings this year. We won’t earn at the rate of the first quarter throughout the year, in my view. I think it would be very unlikely, in terms of operating earnings. But the businesses are performing, generally, very well.

6. Insurance acquisition coming

WARREN BUFFETT: One other thing I should mention, and then we’ll get on to the questions, that we can’t announce the name, because it isn’t quite complete in terms of the other party, but we will probably announce, very soon, an acquisition that is a little less — somewhat less — than a billion dollars, so it’s a huge deal, in reference to Berkshire’s size

But it is in the insurance field. I mean, we love the insurance business. It’s been very good to us. We have some terrific managers in that field.

You’ll see it in the first quarter figures, but you’ll also see how we feel about the business by the fact that this acquisition, which I would say is almost certain to go through, will probably get announced in the next few weeks.

We’re looking for bigger acquisitions. We would love to buy something that cost us 5 or $10 billion. Our check would clear, I assure you.

I think we ended the quarter with about 44 billion of cash, not counting the cash in the finance operations. So, at the moment, we’ve got more money than brains and hope to do something about that.

7. Q&A begins

WARREN BUFFETT: Now we’re going to go around the hall here. We’ve got 12 microphones and — get oriented here — and we’ll turn the spotlight on the microphone that is live.

People can line up to get their questions asked. I think we’ve got two microphones, also, in the overflow room.

And like I say, after lunch everybody should come in here because there’s enough people that get so enthralled with shopping that they don’t return. They’d rather shop than listen to me and Charlie, and we’ll have plenty of seats for everybody in this main hall after lunch.

And so, with that, let’s go to — have I forgotten anything, Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: No.

WARREN BUFFETT: OK. (Laughter)

That may be the last you hear from him. You never can tell.

8. What Buffett looks for in managers

WARREN BUFFETT: We’ll go to microphone number 1, please.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Simon Denison-Smith from London.

You talk a lot about the importance of selecting terrific managers.

I’d just like to understand what your three most important criteria are for selecting them, and how quickly you can assess that.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. I’ll give you two different answers.

The most important factor, subject to this one caveat I’m going to give in a second, is a passion for their business.

We are frequently buying businesses from people who we wish to have continue manage than them and where we are, in effect, monetizing a lifetime of work for them.

I mean, they’ve built this business over the years. They’re already rich but they may not be rich in the liquid sense. They may have all their money, or a good bit of it, tied up in the business, so they’re monetizing it. They may be doing it for estate reasons or tax reasons or family reasons, whatever.

But we really want to buy from somebody who doesn’t want to sell. And they certainly don’t want to leave the business.

So we are looking for people that have a passion that extends beyond their paycheck every week or every month for their business.

Because if we hand somebody a hundred million or a billion dollars for their business, they have no financial need to work. They have to want to work. And we can’t stand there with a whip. We don’t have any contracts at Berkshire. They don’t work, as far as I’m concerned.

So we hope that they love their business and then we do everything possible to avoid extinguishing, or in any way dampening, that love.

I tell students that what we’re looking for when we hire somebody, beyond this passion, we’re looking for intelligence. We’re looking for energy. And we’re looking for integrity.

And we tell them, if they don’t have the last, the first two will kill you.

Because if you hire somebody without integrity, you really want them to be dumb and lazy, don’t you? I mean, the last thing in the world you want is that they are smart energetic. So we look for those qualities.

But, we have generally — when we buy businesses, it’s clear to us that those businesses are coming with managers with those qualities in them. Then we need to look into their eyes and say, do they love the money or do they love the business?

And if they love — there’s nothing wrong with liking the money. But if — what it’s really all about is that they built this business so they can sell out and cash their chips and go someplace else, we have a problem, because right now we only have 16 people at headquarters and we don’t have anybody to go out and run those businesses.

So we — it’s necessary that they have this passion and then it’s necessary that we do nothing to, in effect, dampen that passion. Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yeah. The interesting thing is how well it’s worked over a great many decades and how few people copy it. (Laughter and applause)

9. Buffett on beer industry and its history

WARREN BUFFETT: Go to microphone 2, please.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Good morning, Warren and Charlie. My name is Walter Chang and I’m from Houston, Texas.

Can you describe how you made your investment decision to invest in Anheuser-Busch and how you estimated its intrinsic value? How long did it take you to make this decision?

And is Budweiser inevitable, like Coca-Cola?

WARREN BUFFETT: I’m still drinking Coca-Cola.

The meeting might get a little exciting if I we were drinking Bud here. (Laughter)

We don’t get into much in the way of description of things we might be buying or selling, but the decision takes about two seconds.

But I bought 100 shares of Anheuser about — I haven’t looked it up — but I would say, maybe, 25 years ago when I bought 100 shares of a whole lot of other things .

And I do that so I can get the reports promptly and directly. You can get them to your brokerage firm, but I’ve found that it’s a little more reliable to put the stock in a direct name.

So I’ve been reading the reports for at least 25 years and I observe, just generally, consumer habits, and at a point — currently, the beer industry sales are very flat.

Wine and spirits have gained in that general category at the expense of beer. So if you look at the industry figures, they’re not going anywhere.

Miller’s has been rejuvenated to some degree. So Anheuser, which has had a string of earnings gains that have been quite substantial over the years and market share gains, is experiencing, as they’ve described — and they just had a conference call the other day — is experiencing very flat earnings, having to spend more money to maintain share, in some cases, having promotional pricing.

So they are going through a period that is certainly less fun for them than was the case a few years ago.