#while identifying with a female character you need to change the narrative that's actually presented to you

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

oh man i have a Lot of thoughts about the autopsy of jane doe, both positive and critical For Sure, i'd be SO excited to see your analysis of it! definitely keeping an eye out for that 👀

thanks! i'm working on something article-like to talk about the film and i don't know what i want to do with it yet lol but if i don't post it on here i'll definitely link it. it's mainly a discussion of gender in possession/occult films in the same way that carol clover describes in men, women, and chainsaws - that there are dual plot lines in occult films, usually gendered masculine and feminine respectively, where the "main" feminine plot (the actual possession) is actually a way to explore the "real" masculine plot (the emotional conflict of the "man in crisis" protagonist). typically the man in crisis is too masculine, or "closed" emotionally, where the woman is too "open," which is why she acts as the vehicle for the supernatural occurrence as well as the core emotions of the film. the man has to learn how to become more open (though if he becomes too open, like father karras in the exorcist, he has to die by the end - he has to find a happy medium, where he doesn't actually transgress gender expectations too much. clover calls this state the "new masculine," and we might apply the term "toxic masculinity" to the "closed" emotional state). part of the "opening up" feature of the story is that it allows men to be highly emotionally expressive in situations where they otherwise might not be allowed to, which is cathartic for the assumed primary audience of these films (young men). another feature of the genre is white science vs black magic (once you exhaust the scientific "rational" explanations, you have to accept that something magic is happening). the autopsy of jane doe does this even more than the films she discusses when she published the book in 1992 (the exorcist, poltergeist, christine, etc) because the supernaturally influenced young woman who becomes this kind of vehicle is more of an object than a character. she doesn't have a single line of dialogue or even blink for the entire runtime of the movie. the camerawork often pans to her as if to show her reactions to the events of the movie, which seems kind of pointless because it's the same reaction the whole time (none) but it allows the viewer to project anything they want onto her - from personal suffering to cunning and spite.

compare again to the exorcist: is the story actually about regan mcneil? no. but do we care about her? sure (clover says no, but i think we at least feel for her situation lol). and do we get an idea of what she's like as a person? yes. even though her pain and her body are used narratively as a framework for karras' emotional/religious crisis, we at least see her as a person. both she and her mother are expendable to the "real" plot but they're very active in their roles in the "main" plot - our "jane doe" isn't afforded even that level of agency or identity. so. is that inherently sexist? well, no - if there were other women in the film who were part of the "real" plot, i would say that the presence of women with agency and identity demonstrate enough regard for the personhood of women to make the gender of the subject of the autopsy irrelevant. but there are none. of the three important women in the film, we have 1) an almost corpse, 2) an absent (dead) mother, and 3) a one dimensional girlfriend who is killed off for a man's character development/cathartic expression of emotions. all three are just platforms for the men in crisis of this narrative.

and, to my surprise, much of the reception to the film is to embrace it as a feminist story because the witch is misconstrued as a badass, powerful, Strong Female Character girl boss type for getting revenge on the men who wronged her, with absolutely no consideration given to what the movie actually ends up saying about women. and the director has said that he embraces this interpretation, but never intended it. so like. of course you're going to embrace the interpretation that gives you critical acclaim and the moral high ground. but it's so fucking clear that it was never his intention to say anything about feminism, or women in general, or gender at all. so i find it very frustrating that people read the film that way because it's just. objectively wrong.

there's also things i want to say about this idea that clover talks about in a different chapter of the book when she discusses the country/city divide in a lot of horror (especially rape-revenge films) in which the writer intends the audience to identify with the city characters and be against the country characters (think of, like, house of 1000 corpses - there's pretty explicit socioeconomic regional tension between the evil country residents and the travelers from the city) but first, they have to address the real harm that the City (as a whole) has inflicted upon the Country (usually in the forms of environmental and economic destruction) so in order to justify the antagonization the country people are characterized by, their "retaliation" for these wrongs has to be so extreme and misdirected that we identify with the city people by default (if country men feel victimized by the City and react by attacking a city woman who isn't complicit in the crimes of the City in any of the violent, heinous ways horror movies employ, of course we won't sympathize with them). why am i bringing this up? well, clover says this idea is actually borrowed from the western genre, where native americans are the Villains even as white settlers commit genocide - so they characterize them as extremely savage and violent in order to justify violence against them (in fiction and in real life). the idea is to address the suffering of the Other and delegitimize it through extreme negative characterization (often, with both the people from the country and native americans, through negative stereotyping as well as their actions). so i think that shows how this idea is transferred between different genres and whatever group of people the writers want the viewers to be against, and in this movie it’s happening on the axis of gender instead of race, region, or class. obviously the victims of the salem witch trials suffered extreme injustice and physical violence (especially in the film as victim of the ritual the body clearly underwent) BUT by retaliating for the wrongs done to her, apparently (according to the main characters) at random, she's characterized as monstrous and dangerous and spiteful. her revenge is unjustified because it’s not targeted at the people who actually committed violence against her. they say that the ritual created the very thing it was trying to destroy - i.e. an evil witch. she becomes the thing we're supposed to be afraid of, not someone we’re supposed to sympathize with. she’s othered by this framework, not supported by it, so even if she’s afforded some power through her posthumous magical abilities, we the viewer are not supposed to root for her. if the viewer does sympathize with her, it’s in spite of the writing, not because of it. the main characters who we are intended to identify with feel only shallow sympathy for her, if any - even when they realize they’ve been cutting open a living person, they express shock and revulsion, but not regret. in fact, they go back and scalp her and take out her brain. after realizing that she’s alive! we’re intended to see this as an acceptable retaliation against the witch, not an act of extreme cruelty or at the very least a stupid idea lol.

(also - i hate how much of a buzzword salem is in movies like this lol, nothing about her injuries or the story they “read” on her is even remotely similar to what happened in salem, except for the time period. i know they don’t explicitly say oh yeah, she was definitely from salem, but her injuries really aren’t characteristic of american executions of witches at all so i wish they hadn’t muddied the water by trying to point to an actual historical event. especially since i think the connotation of “witch” and the victims of witch trials has taken on a modern projection of feminism that doesn’t really make sense under any scrutiny. anyway)

not to mention the ending: what was the writer intending the audience to get from the ending? that the cycle of violence continues, and the witch’s revenge will move on and repeat the same violence in the next place, wherever she ends up. we’re supposed to feel bad for whoever her next victims will be. but what about her? i think the movie figures her maybe as triumphant, but she’s going to keep being passed around from morgue to morgue, and she’s going to be vivisected again and again, with no way to communicate her pain or her story. the framework of the story doesn’t allow for this ending to be tragic for her, though - clearly the tragedy lies with the father and son, finally having opened up to one another, unfortunately too late, and dying early, unjust deaths at the hands of this unknowable malignant entity. it doesn’t do justice to her (or the girlfriend, who seems to be nothing but collateral damage in all of this - in the ending sequence, when the police finds the carnage, it only shows them finding the bodies of the men. the girlfriend is as irrelevant to the conclusion as she is to the rest of the plot).

but does this mean the autopsy of jane doe is a “bad” movie? i guess it depends on your perspective. ultimately, it’s one of those questions that i find myself asking when faced with certain kinds of stories that inevitably crop up often in our media: how much can we excuse a story for upholding regressive social norms (even unintentionally) before we have to discount the whole work? i don’t think the autopsy of jane doe warrants complete rejection for being “problematic” but i think the critical acclaim based on the idea that it’s a feminist film should be rejected. i still consider it a very interesting concept with strong acting and a lot of visual appeal, and it’s a very good piece of atmospheric horror. it’s does get a bit boring at certain points, but the core of the film is solid. it’s also not trying to be sexist, arguably it’s not overtly sexist at all, it’s just very very androcentric at the expense of its female characters, and i’m genuinely shocked that anyone would call it feminist. so sure, let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water, but let’s also be critical about how it’s using women as the stage for men’s emotional conflict

also re: my description of this little project as “a film isn’t feminist just because there’s a woman’s name in the title” - i actually don’t want to skim over the fact that “jane doe” isn’t a real name. of the three women in the film, only one has a real name; the other two are referred to by names given to them by men. i’ll conclude on this note because i want to emphasize the lack of even very basic ways of recognizing individual identity afforded to women in this film. so yeah! the end! thanks for your consideration if you read this far!

#the autopsy of jane doe#men women and chainsaws#horror#also to be clear i'm not saying that the exorcist is somehow more feminist because. it's not. i'm just using it as a frame of reference#you'd think a film from 2016 would escape the ways gender is constructed in one from 1973 but that's not really the case#i actually rewatched the end of the movie to make sure that what i said about the girlfriend's body not being found at the end was accurate#and yeah! it is! the intended audience-identified character shifts to the sheriff who - that's right! - is also a man#the camerawork is: shot of the dead son / shot of the sheriff looking sad / shot of the dead father / shot of the sheriff looking sad /#shot of jane doe / shot of the sheriff looking upset angry and suspicious#which is how we're supposed to feel about the conclusion for each character#the girlfriend is notably absent in this sequence#anyway! this is less about me condemning this movie as sexist and more about looking at how women in occult horror#continue to be relegated to secondary plot lines at best or to set dressing for the primary plot line at worst#and what that says about identification of viewers with certain characters and why writers have written the story that way#i think the reception of the film as Feminist might actually point to a shift in identification - but to still be able to enjoy the movie#while identifying with a female character you need to change the narrative that's actually presented to you#hence the rampant impulse to misinterpret the intention of the filmmakers#we do want it to be feminist! the audience doesn't identify with the 'default' anymore automatically#i think that's actually a pretty positive development at least in viewership - if only filmmakers would catch up lol#oh and i only very briefly touched on this here but the white science vs black magic theme is pretty clearly reflected in this film also

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think that if Zutara was canon, the people who justify Kataang by saying that it's canon would've shipped Zutara instead?

Some of them would. Really, it depends on a lot of factors, like why people ship things in the first place. Some people are only interested in canon pairings, and some people who ship KA definitely are those kinds of people. But it also depends HOW it's presented if zutara were canon.

What I mean is, yes, it's true that some people ship things based on whether they are canon, but it's also true that some people who ship KA do so because the narrative leads us to hope Aang will get with Katara in the end, because we've been watching him crush on her from the first episode. The show wants us to identify with Aang's crush, which of course is one of the big criticisms of people who don't feel like KA prioritizes Katara's feelings enough. But if you're one of the viewers who watched the show and identified with Aang the way the show leads you to, then you ship KA.

Let's say zutara does become canon. What does that mean? Does it mean the romance is instead written from Zuko's perspective? If that were the case, the people who ship KA because they identify with Aang's crush would likely also ship zutara in this theoretical scenario. However, a lot would have to be different about the show for us to conceive of it this way. Zuko isn't positioned as the hero of the story, especially not at the beginning. He is A hero and a point of audience identification, but the show has to work to get him there because they position him as a villain at first. So if the narrative were to present zutara as the canon romance with the narrative being about Zuko's crush on Katara, a lot would have to change.

That's why a lot of people who identify with Katara ship zutara, because Zuko's relationship with the other characters isn't about Zuko's feelings, and when it is, it's about how Zuko has to change to meet the needs of the other characters, not the other way around.

The other theoretical canon zutara scenario is the one I see most zutara stans advocating for, the one where not much changes in the main narrative of the show, but have Aang's crush on Katara remain unreciprocated while growing Katara and Zuko's relationship into something romantic. This sort of narrative can be done, and is a more popular way of writing young adult media nowadays than it was twenty or so years ago, because conversations about what girls want and consent are more prevalent than they used to be.

Of course, even in narratives that do prioritize a female character's feelings, you still get people who will only identify with a male character or prioritize his feelings, because even though the Nice Guy narrative has gotten a lot of criticism in recent years, it still exists, and has existed for a long time.

I also tend to the think that no matter how well zutara was written and how it prioritized Katara's feelings, you'd still have people screaming about how Zuko is a bad boy who is corrupting Katara and leading her astray from wholesome good guy Aang, because people already say that and Katara and Zuko only hug platonically onscreen. As I said, the nice guy narrative is so prevalent in our society that people imagine that it's there even when it isn't. Which is actually really quite meta, because Aang did the same thing with Katara in "Ember Island Players" when he yelled at her for the imagined actions of her actress and how she didn't magically end up in a relationship with him despite him never once asking her out.

But, again, people ship things for all sorts of reasons and I'm certainly not saying all people who ship KA do so because it's canon or for bad reasons, just as not everyone who ships zutara would have wanted it to be canon or cares whether it is. Some people ship characters who never interact in canon and that's perfectly valid, too. That's the main problem with the "it's canon" justification, because at the end of the day, people ship things for all sorts of reasons, and a lot of people have really good and creative reasons for why they ship stuff. In my view, whether something is canon or not is one of the least interesting reasons to ship something, because most of my participation in fandom is about whether or not there's a story to explore, and noncanon ships usually have the most untapped potential. But that's just me.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Green Knight (2021)

(CONTAINS SPOILERS)

The Green Knight (2021), with its excellent cast and feast of visual storytelling, does cut a pretty trailer, but it’s hardly the adaptation we’ve all waited nearly 2 years to see. Rather on the slow side, there is plenty of breathing room (often to excess), but often feels wanting. The performances are well-played, albeit terribly subdued, which create interludes that feel tedious. Dev Patel has proven himself time and again that he has the capacity to play a nuanced lead, and he does well here, but it is the side characters that break the monotony and steal the show, most notably Joel Edgerton (Lord), Erin Kellyman (Winifred), and Barry Keoghan (Scavenger).

David Lowery’s “adaptation” explores the journey of an untested and somewhat undeserving not-quite-Sir Gawain, a far-cry from our Hero in the text, more akin to Prince Hal. This change adds elements to the character with which an audience might more easily identify, and should make this a coming-of-age tale, as well as a moral one; though, this film fails as both.

As a coming-of-age tale, Gawain never quite gets there, and it almost doesn’t matter if he does, because it's not really his tale at all. Nor is this film about morality, not even as a cautionary tale. Perhaps it's more accurate to call it an instance of ‘careful what you wish for’. Gawain doesn’t seem to know what he wants. Does he really want to be a Knight? Is this about living an honest life or living up to familial expectations, particularly your mother's? Hard to say, as many of the female characters, including Gawain’s mother (Morgause and Morgan Le Fay made one), are treated as mystery elements themselves. It’s also not clear just how far her control extends, if it has any limitations. Is there anything in this world that is true?

Perhaps we'll never know his mother's true intentions; it clearly wasn't for her son to be his own person and make his own decisions. A man simply doesn’t become a Legend without his mother’s entire fabrication of the quest, it would seem. Does Gawain feel so out of place in his own story because it’s already set out for him? Was Morgan Le Fay simply Lowery’s segue for the concept of Legend as a set path for Gawain to follow? But as such, Gawain’s tale of morality isn’t what it seems, as he doesn’t even have the illusion of choice. Or was it all just a journey back to nature, back to green? Lowery never lets us forget just what color matters most here. There’s even a fun monologue about it! Even the design of the Green Knight is just a little too on the nose; his appearance essentially being that of an ent.

About 2/3 of the way through, The Green Knight actually shows a hint of promise, but it is short-lived. In case you haven’t already lost interest with the lengthy side quests; everything turns sour at the arrival of Lord and Lady Bertilak’s castle (simply titled Lord and Lady), and what should be the bulk of our story, the “exchange of gifts” and Gawain’s true test of morality. The “exchange of gifts” is glossed over for a taste of something completely different, as it takes major liberties with not only a core part of our tale, but arguably what’s most memorable about the original. It becomes Lowery’s convoluted vision of a different sort entirely, one where Gawain seemingly refuses to take part in his own story. While possibly an interesting take in itself, it does a disservice to the text, and accomplishes nothing other than an attempt to be shocking.

There’s something richer in the “exchange of gifts” simply not explored in Lowery’s version, or the compulsive need to “subvert”, and the film is poorer for it. How can you even subvert something which you refuse to touch upon? It’s also extremely odd and honestly baffling, that in this day and age, homosexual themes and undertones would be downplayed or outright rejected (as they are here), rather than embraced and explored. Altogether, this omission seems a poor choice and a clear indication that Lowery holds little to no affection for the original text. Disregarding the “exchange of gifts”, the journey becomes something vain and hollow; perhaps intentionally, but doesn't serve anyone, least of all the story.

Following the tale’s example, the girdle (sans the accompanying scar) is the all-encompassing symbol for Gawain’s shame, but Lowery takes it a step further, in which he is so seduced by its promise of protection that he literally soils it with his lust. But this scene is so abrupt at the all too brief “exchange of gifts” (in a film that stretches everything to excess) that it seems to lack consideration and its only purpose is to disturb. The girdle furthermore becomes a symbol of his unearned and unholy life (which we’re shown), were he to continue to fail to accept his fate and his test, although this too seems superfluous. What’s interesting here is that in either scenario, Gawain remains undeserving. He is not especially virtuous, he’s not even decent from what we can see, and has failed in almost every chivalric aspect; after all, he is “no knight”. Even so, in the original, even the Green Knight can’t begrudge his lack of fidelity in this one aspect; “because you wanted to live, so I blame you the less”.

A message of The Green Knight seems to be acting out of selflessness as the only indicator of a truly good deed, with no expectation of reward. This is evident in the dismissal of the “exchange of gifts” and Winifred’s admonishment, "Why would you ever ask me that?", but this message is so muddled within the world of the film, that it’s somehow also completely out of place. After all, Gawain is rewarded in a way, with several of his trappings, which are returned to him after being stolen. Speaking of rewards for good deeds, religious themes are also notably lacking, favoring the pagan angle (as expected of A24), though which is never expounded upon. There is the decision to keep some not-so-subtle imagery of crippled Christianity; i.e Gawain’s shield (with Mary’s visage on the inside and a small pentangle on the exterior) and a cross at the Green Chapel.

Lowery gets too hung up on a confused mix of vague and painfully obvious ideas of symbolism and makes huge, unwarranted leaps. His work here reeks of self-indulgence, to the point of parody. It’s also simply never clear what anyone’s intentions are, his least of all. His ideas are so flighty and changeable that contradictions abound in the finished product (It’s clear why he needed all that extra time to re-cut). The whole thing is so nebulous that it may fool some into thinking it’s beyond their grasp, but it just reads as pretentious. The thing is, The Green Knight tries to be too many things at once, and in doing so, fails at all of them. Lowery lacks the conviction to support anything he presents and has no sense of narrative structure. Simply put, this film lacked proper direction and would have greatly benefited from fresh eyes on the script.

The Green Knight may question 'What is Honor and if it does exist, what is it worth? For even if there comes a time to prove yourself for Honor’s sake, what is it all for? “Is this all there is?”’, but Lowery drops the concept of Honor as soon as he picks it up and chooses to explore Legacy and Legend, and while it leads us on an interesting journey of interpretation, it’s very heavy-handed. It’s also difficult to answer any of these questions because Gawain is simply not worthy of anything. It’s not just that he is imperfect; he is not good and never acts out of selflessness or for the actual sake of Honor. He doesn’t know the meaning of the word. The original text asks us to stay true, true to our word and our values, in uncertainty and despite our fears (as a Good Knight should, and which Gawain ultimately is.) Lowery, on the other hand, begs us to forget the narrative, because he doesn’t know how to do it, and the search for meaning, because there is none. I’m not even sure he knows what he’s made.

Overall, though heavily burdened by its sluggish pace and lack of structural integrity, The Green Knight, at least on the surface, appears to be a somewhat earnest attempt at exploration within the fantasy/horror genre, asking a lot more questions than it answers. But while its visuals may dazzle, it’s a cold and unfeeling thing, devoid of all charm of the original tale, and can hardly be called an adaptation for many of its choices.

Source: https://letterboxd.com/avega007/film/the-green-knight/

(I wasn’t expecting to go off when I just got a letterboxd, but this film left me heated.)

#the green knight#sir gawain and the green knight#david lowery#dev patel#I really wanted to like it#but it disappointed me#spoilers

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Wings of Temperance

A Possible Influence Behind the Color of Hawks’ Wings

A deck of tarot cards is made up of 78 cards, and the first twenty two are known as the Major Arcana. They were created in the 14th or 15th century but were not used for divination purposes until the 18th century. Tarot card readings are not meant to predict the future but to offer spiritual guidance.

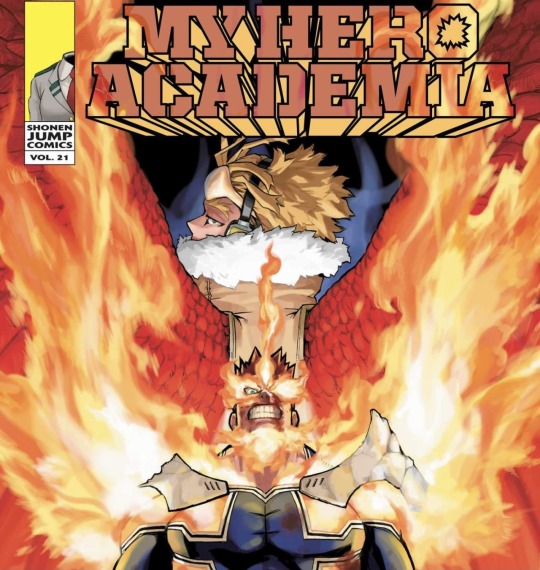

The image above (from Oracloo) depicts the 14th Major Arcana card in the tarot deck which is known as: XIV Temperance.

Like me, I’m sure that your mind jumped to a certain pro hero as soon as you saw the figure’s red wings.

What might Temperance have to do with Hawks? Let’s first look at a couple definitions of the word first. According to Merriam-Webster:

Temperance

1. moderation in action, thought, or feeling

2. habitual moderation in the indulgence of the appetites or passions

If Temperance is drawn, it means:

Balance, patience, and moderation in life.

To think before we act. To look at both sides of an issue, to walk in another’s shoes or their path before we pass judgement. To be compassionate, considerate and fair in our dealings with others (bluestartarot).

That you have a clear, long-term vision of what you want to achieve. You are not rushing things along; instead, you are taking your time to ensuer that you do the best job you can. You know you need a moderate, guided appraoch to reach your goals (biddytarot).

Other Red-Winged Figures

Before we begin I’m going to point out that there are a couple other Red-Winged figures amongst the Major Arcana.

I’m not aware if nudity in art is allowed on Tumblr so just to be safe, I cut the bottom half of both these cards because they depict nude individuals.

The tarot card on the right is VI The Lovers and XX Judgement. Out of the two, I think you could perhaps make some connections with Judgement and Hawks but I think that Temperance works the best.

Symbols of the 14th Arcana

There are quite a few symbols on XIV Temperance, but I’m going to focus on a select few. Interpretations may differ based on the source but I tried to stick with those that were repeated throughout the different websites I read through.

The most important part of this card is the act of pouring water from one cup to another, signifying a balance of duality and a mixture of two separate objects. This is where the card gets its name, the process is called “tempering” which is a slow process to eventually find a perfect middle ground (wemystic).

Other dualities that is represented on this card can be: male/female, spiritual/physical, emotion/logic, conscious/subconscious and subconscious/superconscious (we mystic).

Temperance revolves around supreme balance. One foot is on land which represents the Earthly, material world and the other is in water, which represents the emotional, subconscious world.

The winding path leading to the mountains represents the journey through life with its twists and turns. The sun, appearing as a glowing light is a symbol of staying true to one’s life purpose and meaning (biddytarot).

Fire/Red wings: Physical passion, anger. Muscles and strength necessary to maintain composure and reach a higher being state.

Blue water: Emotions, peace, calm. Groundness and refreshment.

White gown: Pure thought.

Yellow Iris: Communication, thoughts, learning, feminine/masculine.

Temperance’s wings are either referred to as “fire wings” or “red wings.” If we want to make connections to we can argue that his Fierce Wings Quirk is the source of his physical strength, even though he displays some insecurity about his back not being “reassuring” enough for others to depend on.

Other than his red wings, I don’t think I’m confident enough to draw a clear connection between his appearance and the other prominent colors that appear on Temperance. Hawks’ visor was blue before the anime chose yellow, and he does have the yellow color palette going on.

However, the meanings of the colors do line up with Hawks’ character. He is a character who is always trying to be calm and collected no matter the situation. Hawks is a character who is constantly seeking, taking in, gathering, and analyzing information. According to the fandom website, Hawks’ surname translates as: “hawk” (taka 鷹) + “see, visible, idea” (mi 見 )

While his first name translates as: “disclose, open, say” (kei 啓) + “enlightenment, understanding” (go 悟).

Sun: Also appearing as the angel’s third eye, it represents the merging of personal aims with the universe’s plans for the individual.

So similar to many others, I like to see Endeavor as the sun to Hawks’ Icarus (side note: I also like to see Dabi as Apollo in the Icarus theme).

The bit about the eye is interesting as well: I believe that eyes play an important role in the story telling with Hawks, Endeavor and other characters. There are interesting similarities between the two characters and the Egyptian Gods Ra and Horus (@/bokunowtv also pointed out some interesting details as well).

Recently, it also seems like Hawks’ storyline will be intertwining with Endeavor’s. Hawks has expressed verbally in Chapter 299: “Starting with my origin, so to speak... Endeavor’s in trouble.” While they did team up professionally as heroes in the past, it seems that Hawks intentions this time will be personal. We have yet to see what he is planning to do and how things might pan out, however this path will probably lead him to Touya.

Triangle: Representative of the fire element and holy trinity.

Although Hawks does not wear a triangle or square on his chest like the angel, it is still interesting to note that he wears the Hero Public Safety Commission’s diamond symbol in about the same place. Again, there is the mention of fire again.

The Angel

Because Temperance has to do with balance and duality, the angel on the card is both masculine and feminine.

Whether they are just an unnamed angel or a Biblical angel depends on the source you are looking at. However when it comes to identifying them, while one states that it is the Archangel Gabriel, the sources I looked at overwhelmingly pointed towards the Archangel Michael.

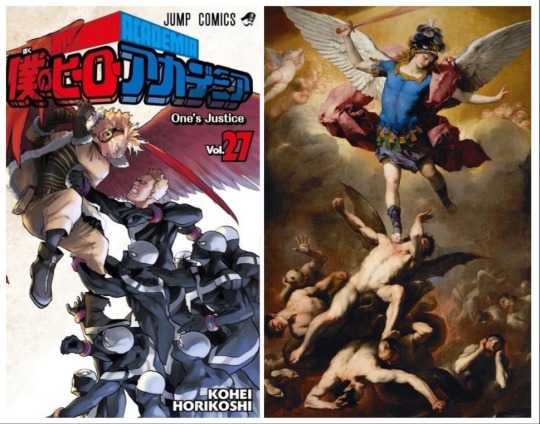

This is very, very interesting considering that the Archangel Michael is the angel who is in all the paintings that people were comparing the cover of Volume 27 with, specifically the painting above: “The Fall of the Rebel Angels” by Luca Giordano.

My analysis first post on Tumblr had to do with pointing out similarities between the Archangel Michael and Hawks, and what that could mean. And my most recent post revisits the possible angel narrative which may be present in Hawks’ story, and how he is referred to as a “fallen angel.”

It’s exciting to see the Archangel Michael pop up again. Michael was also God’s angel of destruction and on XIV Temperance we see him tempering or blending his passionate anger with consicious thought to blend his fiery nature with his super-consciousness with calm (blustartarot).

Temperance Reversed

When Tarot cards are reversed, their definitions are flipped over.

When XIV Temperance meets XV The Devil we see imbalance, disharmony, indifference and lack of empathy. When we preactice excess in our lives without moderation and balance whether it be food, alcohol, drugs, and relationships, we lose ourselves in addiction and bondage (bluestartarot).

May call for a period of self-evaluation in which you can re-examine your life priorities. Self-healing: by creating more balance and moderation in your life (biddytarot).

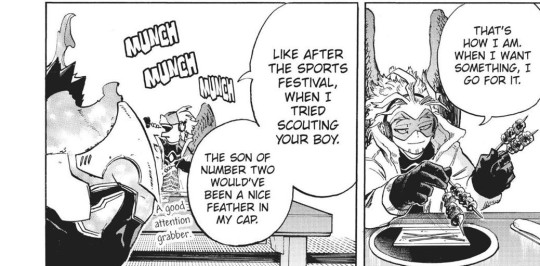

We’ve seen Hawks indulge in something or trip up a couple of times. In Chapter 186, Hawks asks if he can have Endeavor’s leftover food and Endeavor calls him a glutton. Additionally, @/scarletrain1724 has done some analysis on how Hawks is a character who is often seen around or consuming food.

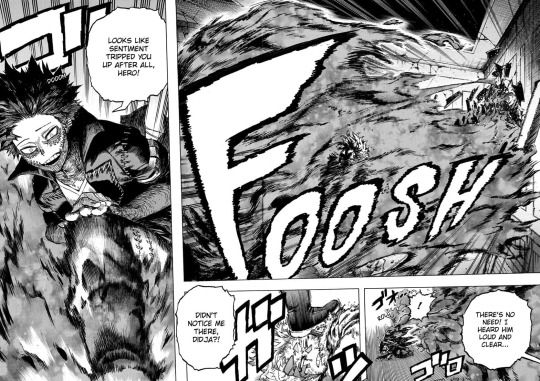

And in Chapter 265, Hawks takes Jin’s life. As Dabi states below, “sentiments” tripped him up. Hawks displays a lack of empathy here. He believes that he feels sorry for Jin and wants to help him, but Hawks is actually unable to understand him properly. I would also identify this action as one of Hawks’ narrative Icarus falls.

The Moral of Icarus’ Fall

This all ties in nicely as we see Hawks’ character following an Icarus narrative. There are a handful of “morals” that we the reader are supposed to gain from the Fall of Icarus but I’ll pull an excerpt from the part I’d like to focus on.

Before taking flight, Daedalus warned his son:

“Take care to fly halfway between the sun and the sea. If you fly too high, the sun’s heat will melt the wax that bids your wings. If you fly too low, the sea’s mist will dampen the feathers that give you life. Instead, aim for the middle course and avoid extremes.” (The Fall of Icarus - adapted from Metamorphoses by Ovid)

As we all know, Icarus does not heed his father’s warning, whether it be cause he purposely ignored him or forgot and flies up towards the sun. The sun’s heat melts the wax and loosens the feathers on his manmade wings, and he plummets in to the ocean below, drowning.

Avoid extremes, fly in the middle and seek temperance.

The card that comes before Temperance is XIII Death.

In death we go through transition, a rebirth, changes and with these we come to XIV Temperance for the need to take the time to pause and think. To integrate and blend what we have learned on our journey (bluestartarot).

So the question to ask is, has Hawks learned anything from his actions or will his story end with him drowning in the ocean?

To those who were able to make it through this post, thank you! I know that it was really long but I didn’t want to divide it into more than one part. I really appreciate your time and attention! :)

#visual#hawks#takami keigo#bnha analysis#mha analysis#mythological influences#religious influences#bnha#mha#bnha meta#mha meta#luna writes#my post

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

CW for discussion of suicide

- She's the crazy ex-girlfriend - What? No, I'm not. - She's the crazy ex-girlfriend - That's a sexist term! - She's the crazy ex-girlfriend - Can you guys stop singing for just a second? - She's so broken insiiiiiide! - The situation's a lot more nuanced than that!

There’s the essay! You get it now. JK.

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is the culmination of Rachel Bloom’s YouTube channel (and the song “Fuck Me, Ray Bradbury” in particular where she combined her lifelong obsession with musical theatre and sketch comedy and Aline Brosh McKenna stumbling onto Bloom’s channel one night while having an idea for a television show that subverted the tropes in scripts she’d been writing like The Devil Wears Prada and 27 Dresses.

The show begins with a flashback to teenage Rebecca Bunch (played by Bloom) at summer camp performing in South Pacific. She leaves summer camp gushing about the performance, holding hands with the guy she spent all summer with, Josh Chan. He says it was fun for the time, but it’s time to get back to real life. We flash forward to the present in New York, Rebecca’s world muted in greys and blues with clothing as conservative as her hair.

She’s become a top tier lawyer, a career that she doesn’t enjoy but was pushed into by her overprotective, controlling mother. She’s just found out she’s being promoted to junior partner, and that’s just objectively, on paper fantastic, right?! ...So why isn’t she happy? She goes out onto the streets in the midst of a panic attack, spilling her pills all over the ground, and suddenly sees an ad for butter asking, “When was the last time you were truly happy?” A literal arrow and beam of sunlight then point to none other than Josh Chan. She strikes up a conversation with him where he tells her he’s been trying to make it in New York but doesn’t like it, so he’s moving back to his hometown, West Covina, California, where everyone is just...happy.

The word echoes in her mind, and she absorbs it like a pill. She decides to break free of the hold others have had over her life and turns down the promotion of her mother’s dreams. I didn’t realize the show was a musical when I started it, and it’s at this point that Rebecca is breaking out into its first song, “West Covina”. It’s a parody of the extravagant, classic Broadway numbers filled with a children’s marching band whose funding gets cut, locals joining Rebecca in synchronized song and dance, and finishing with her being lifted into the sky while sitting on a giant pretzel. This was the moment I realized there was something special here.

With this introduction, the stage has been set for the premise of the show. Each season was planned with an overall theme. Season one is all about denial, season two is about being obsessed with love and losing yourself in it, season three is about the spiral and hitting rock bottom, and season four is about renewal and starting from scratch. You can see this from how the theme songs change every year, each being the musical thesis for that season.

We start the show with a bunch of cliché characters: the crazy ex-girlfriend; her quirky sidekick; the hot love interest; his bitchy girlfriend; and his sarcastic best friend who’s clearly a much better match for the heroine. The magic of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is that no one in West Covina is the sum of their tropes. As Rachel says herself, “People aren’t badly written, people are made of specificities.”

The show is revolutionary for the authenticity with which it explores various topics but for the sake of this piece, we’ll discuss mental health, gender, Jewish identity, and sexuality. All topics that Bloom has dug into in her previous works but none better than here.

Simply from the title, many may be put off, but this is a story that has always been about deconstructing stereotypes. Rather than being called The Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, where the story would be from an outsider’s perspective, this story is from that woman’s point of view because the point isn’t to demonize Rebecca, it’s to understand her. Even if you hate her for all the awful things she’s doing.

The musical numbers are shown to be in Rebecca’s imagination, and she tells us they’re how she processes the world, but as she starts healing in the final season, she isn’t the lead singer so often anymore and other characters get to have their own problems and starring roles. When she does have a song, it’s because she’s backsliding into her former patterns.

While a lot of media will have characters that seem to have some sort of vague disorder, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend goes a step further and actually diagnoses Rebecca with Borderline Personality Disorder, while giving her an earnest, soaring anthem. She’s excited and relieved to finally have words for what’s plagued her whole life.

When diagnosing Rebecca, the show’s team consulted with doctors and psychiatrists to give her a proper diagnosis that ended up resonating with many who share it. BPD is a demonized and misunderstood disorder, and I’ve heard that for many, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is the first honest and kind depiction they’ve seen of it in media. Where the taboo of mental illness often leads people to not get any help, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend says there is freedom and healing in identifying and sharing these parts of yourself with others.

Media often uses suicide for comedy or romanticizes it, but Crazy Ex-Girlfriend explored what’s going through someone’s mind to reach that bottomless pit. Its climactic episode is written by Jack Dolgen (Bloom’s long-time musical collaborator, co-songwriter and writer for the show) who’s dealt with suicidal ideation. Many misunderstood suicide as the person simply wanting to die for no reason, but Rebecca tells her best friend, “I didn’t even want to die. I just wanted the pain to stop. It’s like I was out of stories to tell myself that things would be okay.”

Bloom has never shied away from heavy topics. The show discusses in song the horrors of what women do to their bodies and self-esteem to conform to beauty standards, the contradiction of girl power songs that tell you to “Put Yourself First” but make sure you look good for men while doing it, and the importance of women bonding over how terrible straight men are are near and dear to her heart. This is a show that centers marginalized women, pokes fun at the misogyny they go through, and ultimately tells us the love story we thought was going to happen wasn’t between a woman and some guy but between her and her best friend.

I probably haven’t watched enough Jewish TV or film, but to me, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is the most unapologetic and relatable Jewish portrayal I’ve seen overall. From Rebecca’s relationship with her toxic, controlling mother (if anyone ever wants to know what my mother’s like, I send them “Where’s the Bathroom”) to Patti Lupone’s Rabbi Shari answering a Rebecca that doesn’t believe in God, “Always questioning! That is the true spirit of the Jewish people,” the Jewish voices behind the show are clear.

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend continues to challenge our perceptions when a middle-aged man with an ex-wife and daughter realizes he’s bisexual and comes out in a Huey Lewis saxophone reverie. The hyper-feminine mean girl breaks up with her boyfriend and realizes the reason she was so obsessed with getting him to commit to her is the same reason she’s so scared to have female friends. She was suffering under the weight of compulsory heterosexuality, but thanks to Rebecca, she eventually finds love and friendship with women.

This thread is woven throughout the show. Many of the characters tell Rebecca when she’s at her lowest of how their lives would’ve never changed for the better if it wasn’t for her. She was a tornado that blew through West Covina, but instead of leaving destruction in her wake, she blew apart their façades, forcing true introspection into what made them happy too.

Rebecca’s story is that of a woman who felt hopeless, who felt no love or happiness in her life, when that’s all she’s ever wanted. She tried desperately to fill that void through validation from her parents and random men, things romantic comedies had taught her matter most but came up empty. She tried on a multitude of identities through the musical numbers in her mind, seeing herself as the hero and villain of the story, and eventually realized she’s neither because life doesn’t make narrative sense.

It takes her a long time but eventually she sees that all the things she thought would solve her problems can’t actually bring her happiness. What does is the real family she finds in West Covina, the town she moved to on a whim, and finally having agency over herself to use her own voice and tell her story through music.

The first words spoken by Rebecca are, “When I sang my solo, I felt, like, a really palpable connection with the audience.” Her last words are, “This is a song I wrote.” This connection with the audience that brought her such joy is something she finally gets when she gets to perform her story not to us, the TV audience, but to her loved ones in West Covina. Rebecca (and Rachel) always felt like an outcast, West Covina (and creating the show) showed her how cathartic it is to find others who understand you.

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is the prologue to Rebecca’s life and the radical story of someone getting better. She didn’t need to change her entire being to find acceptance and happiness, she needed to embrace herself and accept love and help from others who truly cared for her. Community is what she always needed and community is what ultimately saved her.

*

P.S. If you have Spotify... I also process life through music, so I made some playlists related to the show because what better way to express my deep affection for it than through song?

CXG parodies, references, and is inspired by a lot of music from all kinds of genres, musicals, and musicians. Same goes for the videos themselves. I gathered all of them into one giant playlist along with the show’s songs.

A Rebecca Bunch mix that goes through her character arc from season 1 to 4.

I’m shamelessly a fan of Greg x Rebecca, so this is a mega mix of themselves and their relationship throughout the show.

*

I’m in a TV group where we wrote essays on our favorite shows of the 2010s, so here is mine on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, I realized I forgot to ever post it. Also wrote one for Schitt’s Creek.

#crazy ex girlfriend#crazyexedit#cxg#ceg#crazy ex gf#writing#mine#mental illness#bpd#mental health#spotify#music#playlist#essay#*

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tangled Salt Marathon - Keeper of the Spire

You wouldn’t know it upon first watch, but today’s story is one of the few non-filler episodes of season two.

Summary: In order to acquire the third scroll piece, Rapunzel, Eugene, Cassandra and Lance travel to the home of the Keeper of the Spire and meet Calliope who informs them the third piece is kept inside the Spire’s vault at the top of the mountain. The group begins the long journey to the Spire's vault the following day and become increasingly annoyed by Calliope’s rude, arrogant and inconsiderate behavior. Despite Calliope's treatment, Rapunzel insists they still need her help all while they being dangerously pursued by the vault's protector, the Kurlock. The group eventually reach the Spire's vault, but again encounter the Kurlock and discover Calliope is not the real Keeper of the Spire.

Once Again, ‘Destiny’ Isn’t a Goal

If you want to build up some sort of mystery with the scroll pieces and what awaits Rapunzel at the end of her quest, then that’s fine. But at some point you have to actually explain what her destiny actually is, how the scroll connects to it, and most importantly, why she needs to fulfill it.

We’re never given a reason for why Rapunzel needs to reconnect to the moonstone, nor why she couldn’t have just stayed home and did nothing. The scroll itself doesn’t tell her anything and what it leads up to has nothing to do with ‘destiny’ and ultimately comes to nothing in the grand scheme of things.

Indeed, much like the quest itself, things would have been better for everyone had she not found the scroll at all.

Meet the Best Written Character In the Show

No, I’m not exaggerating. Calliope is the only recurring character in the series not to get royally screwed over by last minute rewrites and poor pacing. In fact her arc may have actually been improved by the dumb creative decisions of season three.

Which is a problem because she’s not a main character. Her story and arc shouldn’t be more well rounded than Rapunzel’s. It’s also clear, given how the writers try to pitt her as annoying thorn in the heroes sides that is only tolerated because she’s useful, that they weren’t expecting the general audience to identify with her, and so her subsequent portrayal as the most developed character in the show is fully accidental.

We Finally Get Some Indication of Cassandra’s Age

Well first off, we probably shouldn’t be getting such information about our deuteragonist this late in the game, but also, putting Cass in her early 20s recontextualizes her arc the same way Varian being 14 recontextualizes his conflict, but in the opposite direction. A 24 year old is more accountable for their actions than a 14 year old. Always will be.

And before people try to get all pedantic on me; yes she’s only 23 here, and Varian is currently 15. What I meant is those are their ages at the start of their villain arcs, because the linear progression of time is a thing.

This Joke Actually Highlights One of the Bigger Problems of Season Two

I laughed when I first heard this joke, but that’s cause I was under the assumption that they would go on to develop a friendship between Cass and Lance as the season went on. But they don’t.

Cass never has any focus episodes that aren’t about her failing relationship with Rapunzel. She never interacts with the other four people that she’s traveling with outside of group scenes like this. Not even with Eugene, who we spent the whole previous season establishing a bond with.

This undermines Cassandra’s arc in several ways. She less well rounded and developed without other people in her life besides Rapunzel; it ignores her place in the show as the older and wiser friend if she’s so majorly co-dependent upon only person. It also ignores what was set up in season one in order to push a certain narrative later that clashes with what we the audience already know.

Plus there’s the added effect of other characters getting poor representation within the story.

So Why Didn’t the Others Come Along Again?

I understand not being able to take the caravan upto the top of the mountain, but the road was wide enough to get it up this far. Also it didn’t take you all day to get here so you could just walk back to camp.

But let's get to the real reason why the caravan was left behind. The writers wanted and excuse to get rid of Hookfoot and Shorty. Because they didn’t want to write them into the story. Because they have nothing to do with the overall plot and together they’re one too many characters to keep up with and give stuff to do to. Which begs the question of why they were ever included into the season at all.

Also why leave Adria behind? She was the one who sent them up here. She’s the one who has a vested interest in getting Rapunzel to the end of her journey. She’s the only one driving the plot at the moment, so why not have her present to do just that?

Rapunzel is a Hypocrite

There’s not a single description that Rapunzel says here that couldn’t be applied to herself.

Which would be funny if the writers ever actually acknowledged this within the series.

Having parallels simply exist on their own and not actually inform the story is bad writing. Same with character flaws; acknowledge them, use them to advance both the plot and the characters, and build off of them to establish character dynamics. This is in part why Calliope is the better written character between the two of them.

Behold, the One and Only Time Lance and Rapunzel Hold a Conversation with One Another!

Speaking of characters not getting enough focus.... It’s just a set up for a recurring gag in the episode, but this is indeed the only point in the series where Lance and Rapunzel talk, about anything.

It’s not just Cass who is prevented from establishing relationships, it’s literally everyone. All of Rapunzel’s focus episodes alternate between Cassandra, Eugene, or a random side character. Cassandra only gets focus when with Rapunzel. Eugene only gets development with either Rapunzel or on his own. Lance is only ever shown interacting with Eugene or Adria, outside of some highly specific one off instances like here. Hookfoot is left out in the cold save for three episodes and two of them double as New Dream folder.

We’ve managed to pair the cast down to only six, as opposed to a whole kingdom’s worth of characters, and yet they have less development here than they did in season one. The group does not feel like a group, and that is a problem.

How is This Meant to be Encouraging?

Ok, I get what the writers were going for here. Calliope has low self esteem. she feels useless because she’s lost her only support group, her mentor. So Rapunzel is ‘inspiring’ her to fulfill her dream of becoming the new keeper of the spire.

However, this is an incredibly bad take.

Calliope lacks self esteem because she’s lonely. Her dream of becoming the keeper is directly tied to her father figure, who up till now was the only person who gave a damn about her. She only wants to impress Rapunzel because she wants a friend and she believes that she needs to be useful in order to get that. And here is Rapunzel and the narrative reinforcing that belief under the guise of ‘achieving a dream’.

No fuck that!

You don’t need to have a ‘purpose’ to have friends.You shouldn’t have to prove yourself useful just be respected and included. Also, Rapunzel doesn’t even befriend her. She just uses Calliope to get what she wants and then avoids her for the rest of the show; only checking up on her out of obligation in season three.

So not only are we denied another female friendship in a show bereft of female relationships, but we also have a character who can be easily read as autistic by the audience needing to prove she’s useful to society in order to be accepted.

Ugh!

And yeah, I said autistic. We have a character who fails to pick up on social cues, hyperfixates upon her special interests, is rejected by society for trying to share these special interests, and she even pulls out her magic linked rings to fiddle with when stressed, which can be coded as a stim. I’m not saying that this was the writers’ intent, but nevertheless these are traits that people on the autism spectrum tend to identify with.

So how insulting is it to watch this episode and see someone you could relate to being constantly put down by the heroes behind their back and then never apologize for it, even when said character admits their own fault?

So Are We Ever Going to Get Any Background on this Spire?

So the spire is one of the few places that is plot important in the show. Yet we never find out why it exists, who built it, how it came to hold such important plot devices, nor the story behind the keepers who guard it. It’s just there, and that’s infuriating because it’s both a lack of much needed worldbuilding and lore.

Still A Better Dad than Frederic

Leaving for months on end without telling you loved ones why and where you’re going is a shitty thing to do. Doubly so if its just to teach your kids ‘a lesson’. However, The Keeper still winds up being a better parental figure than most of the other dads (besides Cap, who is awesome) in the series. That’s how low the bar has been dropped by Chris and his weird ideas on parenting.

So What Was the Lesson Here?

Ok first off, Calliope didn’t need to be reminded of anything. The Keeper says as much. She was always persistent. The only lesson that she does learn is not to lie but apparently that’s not what we’re supposed to take from this episode.

But what are we supposed to take away? Because Rapunzel doesn’t learn anything either. There’s no admittance of wrongdoing on her part and she does not change her outlook or behavior from this encounter.

Calliope at least learns to become more self assured after this episode and remains honest and true to herself once the episode is done with. Rapunzel however is the same. You can’t claim that this is ‘Rapunzel’s story’ (Chris’s words not mine) if it’s only random side characters who are allowed to grow. Which is yet another reason why the main cast of characters don't get the development and interaction that they should.

That’s also why Calliope is better written than the main character and she shouldn’t be. It’s a bewilderingly oversight of basic writing.

Conclusion

I don’t mind this episode. As I said in the beginning, it is one of the few non-filler episodes in season two. However, there’s a lot of problems with it to the point where I can’t actually call it good, just mediocre.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another thing I would like to speak about this is my opinion I don’t want to talk over other trans people or the community I’m not speaking for the community as a whole this is just my personal opinion and I would like to state that I respect you and please respect my opinion and the opinions of others. Thank you. Here are some topics brought up that I’ve seen and I want to jsut state and voice my opinion if I offend you in any ways your are free to scroll. I value your opinions your thoughts but please be mindful and respectful of others.

THIS IS HELLA LONG BTW SORRY IN ADVANCE

(But please read the whole thing you don’t have to if you don’t want to)

1. "The vast majority of the individuals who have been examining this are cis, which is an issue first thing"

It truly isn't, there is no issue with this. There's nothing amiss with cishets imparting their insight, since anyone can have an assessment on anything. I see what your saying in some cases the don’t but as you saw on my other post they do in some events and cases the have a freedom to voice there opinions though.

2. I still can't seem to see a 'genderbent' rendition of a male character who needed bosoms and a dfab body. This is the first and most clear motivation behind why 'genderbending' is innately transphobic - it accepts that actual characteristics and sex are something very similar, and that you can't be female without additionally being dfab. (I will say AFAB)

Indeed, more often than not genderbent characters are not given characteristics and such generalizations. In any case, what's the issue with that? There's no issue playing into generalizations. You presently can't seem to see a genderbent adaptation of a male character who needed bosoms and is AFAB. That is narrative, and individual stories can't be acknowledged as obvious proof. Regarding why, the banner appears to introduce their conviction of actuality, when it clearly isn't. There's a lot of male genderbend characters (genderbent to be female) who do need bosoms, yet for what reason would it be advisable for it to significantly matter? Generalizations or not, there ought to be no issue here.

"It expects that actual attributes and sex are something very similar, and that you can't be female without likewise being AFAB." This is indeed another supposition, not a reality. Actual characteristics in sexual orientation are not something very similar, but rather it plays into the reality and generalization that actual attributes in sex jobs/sex generalizations are something very similar, to which they (as a rule) can be. You can be female without likewise being afab, and (expressed by and by) there are numerous characters out there that are trans and were being genderbent (tragically, however we shouldn't actually genderbend trans characters since it eradicates their sexual orientation except if when they're genderbent they're as yet trans, the exact inverse way.) and you could discover numerous trans characters being genderbent or such in games, manga, and media by and large.

3. "This is cissexism, and this is transphobic. The message that 'genderbending' says is that you should have bosoms and a v/gina to be female, and you should have a penis and a level chest to be male. I ought not need to clarify why that message is transphobic."

This isn't cissexism. The genuine meaning of cissexism: "Cis-sex-ism. Noun. Prejudice or discrimination against transgender people.” Stop twisting word’s definitions to fit your appeal and opinion. Stop believing threads such as this when they can’t even use the original definition properly. Genderbending is as simple as twisting someone’s gender so they fit into the stereotype. (a majority of the time, at least.) Biological genitalia are biological genitalia. Gender is defined by your brain, but we obviously cannot show that fact if there was a genderbend, because humans brains quite obviously do not show outside of the skull.

4. “The way 'genderbends' are completed likewise has unmistakably transphobic suggestions by they way it changes out the actual attributes of characters to make them 'the contrary sex' (The notion of there being ‘opposite genders’ is some fresh bullshit that I’ll cover later in this post) For instance, by giving a male character curves and breast’s while 'genderbending' him, the message is evident that this character was cis regardless."

This is being made way deeper than the notion actually is. Switching out physical traits to play into gender roles and gender stereotypes is not bullshit whatsoever. Giving a male character breasts and curves is as simple as what the action actually is. Genderbending, nothing more, nothing less. Nobody is actually reading into how detailed this is besides the original poster. But my issue is, what’s wrong with the message that the character is cis? Is there something wrong with cis people or there being cis characters? Trans people can still fit into these categories, and assuming trans people look different from cis people (whether in fiction or not) is transphobic, not characters fitting into the ‘cis’ category in your opinion. Once again, there is the assumption that the character was cis to begin with (unless the character has been stated on their wiki or in canon to be cis, to which most aren’t usually.

5. "'Genderbending' naturally infers that all characters are cisgender of course, and deletes any chance of these characters being trans. this isn't as plainly transphobic as the main point, yet it is hurtful to trans individuals inside being a fan spaces, as the presumption that all characters are cis until unequivocally expressed in any case pushes us out of media and eliminates whatever portrayal we may attempt to make for ourselves. "

Genderbending doesn't suggest anything, the first banner (and rebloggers) are indeed assuming. This obliges the hurried suspicion false notion, which is a coherent error that shows when a argument I’dbadly made. Genderbending doesn't suggest that all characters are cisgender as a matter, however it infers that the individual who composed this accepts so. There are cis looking trans individuals, and there are so to state, "trans looking" cis individuals. It doesn't eradicate any chance, in light of the fact that there can even now be trans individuals with genderbends, just as the way that there is trans genderbends out there. (despite the fact that it's avoided upon, obviously) It isn't unsafe to anybody at all, considering genderbends are quite often for no particular reason or investigation, there is no supposition that all characters are cis until expressed something else. (also, regardless of whether there is, the thing that's the mischief in that. there's no damage in having cis individuals not be expressed and trans individuals being expressed, on the grounds that cis individuals are the greater part.) It doesn't eliminate any portrayal at all, and I'd prefer to check whether operation really had any sources identifying with that, considering this has no sources at all and explicitly lies on striking allegations and suspicions.

6. "The third issue with 'genderbending' is that it is reliably cis male and cis female, and that is it. I have never seen people 'genderbend' characters by making them nonbinary or intersex. I have never seen a genderbend of a female character which made her a trans male in light of everything. 'Genderbending' proposes that there are only two choices concerning sex: cis male and cis female. There is nothing of the sort as nonbinary individuals inside this philosophy. Intersex individuals are bizarre, best case scenario. Agender individuals are minimal better than a far off fantasy."

Prior to anything: Agender doesn't exist. Non binary isn't actually viewed as a gender what I am saying is Non-binary is not technically considered a gender Non-binary (also spelled nonbinary) or genderqueer is a spectrum of gender identities that are not exclusively masculine or feminine—identities that are outside the gender binary and there is no “opposite” to genderbend a non-binary person there is no "inverse" to genderbend a non-paired individual. In the event that somebody endeavored to "genderbend" a non-binary individual to a male or female, individuals would get vexed regardless of what they wanted. There is indeed, nothing amiss with male and female genderbends. YOU (conversing with operation and the individuals who concur) continue expecting that they're cis, which is more transphobic than what you guarantee is transphobic. You can't "genderbend" a non-binary nor intersex character, or it would be designated "transphobic" or "eradicating their personality" to which it's definitely not. You could ensure that something contrary to non-parallel is intersex (since individuals who are intersex are hermaphrodites, brought into the world with both genetalia logically) however that would likewise recieve more disdain. It doesn't infer anything, and without fail, you expect that a character is cis. For all you know, they could be stealth trans, or openly trans but you never looked at their wiki; or they could not have their gender specified on the wiki or in canon. Agender does exist what I am saying is the gender your trying to portray or the norms when you look it up Some people's gender changes over time. People whose gender is not male or female use many different terms to describe themselves, with non-binary being one of the most common. Other terms include genderqueer, agender, bigender, and more this is. That is what I am saying in that area that people don’t identify as any gender as he/she or some are fluid. yes you could do “opposite” to genderbend a non-binary person. But if someone attempted to “genderbend” a non-binary person to a male or female, people would get upset despite it being what they wanted. But that would be transphobic and defeating the purpose of there identity as a whole. Sorry some of my Japanese was switched out and there are some words do not exist in English I apologize if anyone got offended. Yes you can genderbending a cis male/female to a non-binary individual but that wouldn’t be called genderbending would it?

7. “‘Genderbending’ ignores that it is impossible to make a character ‘the opposite gender’, because there is no such thing as an ‘opposite gender’. Gender is a spectrum, not a binary, but you wouldn’t know that from the way fandom spaces treat it.”

Gender is binary, however binary doesn't mean two. Gender is chosen in the brain. It IS difficult to make a character that is non-binary or intersex the contrary sex on the grounds that there is no opposite gender of non-binarynor intersex, at any rate in the event that you would prefer not to be called transphobic or more. You can make a cis individual a non-binary person but that wouldn’t be called genderbending?? The frigidity of genderbending is when a character's gender is changed. Usually in fanfictions or fanart. The name should be changed since it is heavily confusing since genderbending also means in other definitions gender bending is sometimes a form of social activism undertaken to destroy rigid gender roles and defy sex-role stereotypes, notably in cases where the gender-nonconforming person finds these roles oppressive.

8. “Of course, there are some reasons for ‘genderbending’ cis male characters into cis females that will always get brought up in discussions on the politics of ‘genderbending.’ The most frequent is that cis girls, who only see themselves as one-dimensional characters in media, want to have characters like them who are just as multifaceted and developed as the male characters that we are given, so they make their male faves female to give themselves the representation they desire. This is a decent reason for ‘genderbending’, but it does not excuse the fact that the way in which ‘genderbending’ is done is inherently transphobic, and it gives fans yet another excuse to ignore female characters in favor of focusing on their male faves.” This whole spot I shouldn’t even have to explain. This is once again being read into way too much, there is no ‘politics’ of genderbending. There is just genderbending, plain and simple. Cis girls can want to see stuff in genderbending, as can cis guys when they genderbend a female character male to see how they’d react and such. Genderbending has no politics, besides that it’s “transphobic” to some.

9. “Another reason for ‘genderbending’ that I’ve heard is ‘it’s for the sake of character exploration - like, what if this character had been born as male/female instead?’ This excuse is cissexist and transphobic from first blush. The idea behind it is that someone ‘born as female’, aka with breasts/vagina will automatically be a cis female, allowing fans to explore what that character’s life would have been like if they were female. Why not explore the possibility of a character being designated female at birth, but still identifying as male? Why do you need a character to be cis for you to find their personality and life interesting to explore? Why do you automatically reject the notion of your fave being trans? If you want to explore what it would have been like for your male fave to have struggled with sexism, consider them being a trans woman, or a closeted afab trans person.”

Yes, character exploration. It’s not cissexist nor transphobic. Whether the character was genderbent cis or trans, it’s not about their genetalia to ‘explore’ the character, but that’s just what you thought it was. Character exploration in this case as in “How will people treat them differently due to possible sexist/misogynist laws and/or character behavior that’s normally in males inside a female, or vice versa? How would people and the law treat this female character who’s shy, if she was a male? How would people and the law treat this male character who’s obnoxious and loud and determined, if he was a female?” Not “How different will this character’s life be because they have a penis or v/g?” You reducing character exploration down to genitalia is blatantly transphobic more so than you think, as well as just downright rude.

10. ‘Genderbending’ does harm trans people. It perpetuates dangerous cissexist notions and the idea of a gender binary being a valid construct, erases nonbinary and intersex people, and others trans people. These are what we call microaggressions - they are not as dangerous as outright harassment and assault, but they enforce and support a system and ideology in which we are other, and we are worthy of hate and violence because we do not fit in.

Genderbending does not harm all trans people inherently i am talking to a group of people which is moderately huge but I am not speaking for all of the community whatsoever, considering trans people also like to genderbend characters. It plays into stereotypes and you thinking gender is a spectrum is more harmful that getting upset that someone thinking “How would people treat this character if he/she was the opposite gender?”. It does not erase non-binary nor intersex people, because you could throw them in if you really wanted to, but you’d also be the person who would call that act transphobic or ‘erasing their identity’. This is not a microaggression whatsoever, but rather a personal grudge based on assumptions you think are true, and treating your opinion as fact. That is all.

I don’t see or think why genderbending as a whole is transphobic the name should be changed though but genderbending as a whole is not bad sure they’re are issues but It is not transphobic.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have seen many, MANY discussions/debates about ca:cw and I have never seen anyone mentioning that Rhodey's injury was a metaphor. How did you get that idea?

Short answer: I’ve actually read a lot on the subject. I’m teaching a media studies class right now called “What Can Superheroes Tell Us About Psychology?” (because that’s the kind of shit you can get away with at giant universities) and hoo boy are superhero narratives More Ableist Than Average. Anywhoo, a few of those readings:

I’m quoting hard from the chapter “Hyper-Normative Heroes, Othered Villains: Differential Treatment of Disability in Marvel” in a book on disability studies because it’s free. A relevant passage:

“These metaphorical portrayals all fail to engage with disability as a social category and as an individual identity, thereby ignoring its context… Nick Fury’s missing eye does not change his aim with distance weapons (e.g. Captain Marvel) or piloting software. Instead, it recurs in the films largely in metaphorical lines such as Fury’s commenting on the death of a friend with ‘I just lost my one good eye’… One character in Avengers even questions the lack of accessibility in Fury’s multi-monitor computer console, and Fury’s assistant simply answers that he must turn his head more often to compensate. The franchise thereby emphasizes that Fury’s missing eye is only a metaphor for his discernment and ability to see details that others have missed, rather than a truly integrated part of his character or even an accurate portrayal of that disability.

“8. This treatment of disability as metaphor persists throughout the MCU. In Captain America: Civil War, superhero War Machine incurs a permanent spinal injury while fighting on behalf of his best friend Iron Man. Later on, rival superhero Hawkeye… ‘You gotta watch your back with this guy. There’s a chance he’s gonna break it.’ The film then equips War Machine with a fantastical prosthesis that essentially nullifies his disabled experience through giving him the same range of motion as his non-disabled [abled] teammates, entirely without side effects or need for maintenance. The MCU films thus present disability as a metaphor for inner morality and characterization. War Machine has few experiences of being a disabled man through his spinal injury, but is instead emotionally ‘disabled’ by the damage to his social standing he has incurred through his friendship with Iron Man… The MCU thereby offers no critique of ableism or inaccessibility, instead continuing to localize disability as a problem with the body and the individual.”

Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond by José Alaniz is also a fantastic resource, and you can buy it for money here or hopefully find it at a library if you have no money. A few of the relevant points from his book:

Superhero stories often treat disability as a��“problem” that must be “solved” through in essence nullifying the disabled experience of the character(s) through superpowers that run directly counter to the disabilities and/or fantasy “cures,” e.g.

Daredevil is blind BUT navigates the world in a way similar to sighted people due to his “radar sense,” meaning that he doesn’t get to have a lot of the lived experiences of blind individuals

Don Blake is mobility impaired and uses a cane BUT his cane transforms into mjolnir and imbues him with the power of Thor, meaning that he spends most of the story moving like a nondisabled person

Hawkeye is hard of hearing sometimes in some of the comics, BUT he often gets magical cochlear implants from Tony Stark that cause him to stop being hard of hearing

Characters that are disabled and remain disabled tend to be villains whose villainy is either implied or stated to come directly from their bitterness over being disabled, e.g.

Doctor Doom hates that he’s scarred by an explosion so much that he wants to take over the world to get revenge on the Fantastic Four

The Lizard only transforms himself because he ignores all scientific and ethical boundaries in his desperation to stop being disabled

Doctor Poison is described by herself and other characters as a “monster” for failing to (unlike Wonder Woman) conform to White Western conceptualizations of female beauty

Characters like The Thing, She-Hulk, and Bizarro have the potential for some really interesting disability narratives. However, the same publication pressures that prevent permanent injury or death to the characters also prevent the inclusion of “serious” “real-world” issues like discrimination unless it’s metaphorical (e.g. anti-mutant fearmongering as a metaphor for anti-AIDS prejudice).

The Big Damn Foundational Text on the intersection of disability studies and media studies is Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, and you can pay money for it here but it’s also available at a lot of libraries. Anyway, a couple of relevant points from that book include:

Disability portrayals abound in literature going back to pretty much the dawn of history, but most of those portrayals suck ass because:

Most disabilities are treated as metaphors rather than demographic characteristics, which means that the disabled character doesn’t get connected to other people with disabilities (including those in the real world) and offers no commentary on ableism — if Richard III’s spinal misalignment is just a metaphor for him being “twisted” inside, it doesn’t allow readers with spinal misalignment to identify with him