#which leads me to believe it's a consequence of the blurring between reality and fiction in this season

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

a compilation of some of the similarities between Maestro and the Toymaker...i reckon even if it wasn't stated explicitly, we could've guessed the connection 😉

#this isn't even counting Maestro's treble clef-hair looking like the Toymaker's fright wig#or them both having gorgeous bandleader outfits#i believe that both Ms. Flood and the Doctor have that winking sound effect though#which leads me to believe it's a consequence of the blurring between reality and fiction in this season#i do think that'll be the fault of another of the Toymaker's legions - likely Ms. Flood as the embodiment of Story#...but it's still fun to go 'hahaha look he passed on this trait' 😂#glad to see they both have EXCELLENT emotional regulation 💀#maestro#the toymaker#doctor who spoilers#doctor who#the doctor#fourteenth doctor#fifteenth doctor#ruby sunday

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an Orwellian nightmare, thought crimes are the new “crime”.

You’re gonna tell me, gonna tell anyone what something is based on its ability to render unto you greater power over me and my life. It will be framed, recast, rewritten even, to serve a narrative completely removed from the thing actually being talked about.

Everything is this way.

Some things are easier than others to twist and make a scene about. In said nightmare the purpose is control. The truth isn’t the truth; the truth is what you say it is--you the person or entity in control. And that truth is always self-serving and more than anything, decoupled from reality.

The fact that you’re going to burn my life down over every breath I take, one might learn to just stop existing short of actually ceasing. In fact that is my life, in short, where I have stopped existing. Every facet of my life I’ve let go of, claimed by you, taken by you as an instrument of power. Every relationship, friendship, relative, acquaintance, every activity, hobby, place I used to frequent. Everything a “crime”.

Reduced to suffocating and becoming more dysfunctional just holding my breath waiting for it to be over, my every breath--movement of a muscle--it’s picked apart and scrutinized in this utilitarian fashion. The more dysfunctional I get and the more given to dysfunctional means of coping with what can’t be resolved by conventional means (cause reality can’t even be agreed upon by anyone involved you see--”this” isn’t happening and I’m crazy you see) the more my “savior” has as ammunition to justify their occupation and “management” of my life. I have been consumed by the womb-like warmth of an iron maiden. My understanding of medieval torture devices is lacking, but I find it an apt description of the god-queen amalgamation reigning supreme over my life. I get cut up just breathing.

Everything is “this” way. Everything is an avenue, a door, a means--an opening into me to be used as a tool to the deconstruction of my personhood and humanity. To end a life, literally, actually literally. .....The intentions may not be agreed upon, but that is the result. And last I checked your intentions don’t matter, only the consequences. Your own words to me, “we don’t get to decide when we have and haven’t hurt someone”. It isn’t for the person doing to decide that they’re one thing or another, self-delusionally too often. It’s the person that it’s being done to who has the first and last say to the true costs of the “vivisection” (as though there could be any kind of rhyme or reason to the things you do beyond the acquisition of power and control and “supply”).

In the iron maiden I have survived by becoming smaller and more non-existent. The smaller I’ve gotten the more the grip--the noose--has tightened. The more of my life I surrender to shut the door on you, the further in you have encroached. Absolute suffocation and self-medication become the new reality for me. And moments like this one remind me why existing.... it costs too much. But that’s what the powers that be in said nightmare live for--to absolutely brutalize every kind of self-assertion, to hollow out, to leave compliant, empty shells of people.

Art doesn’t ask your permission. But I’m cast a villain for the smallest, simplest things. How much more so for the brutal honesty of someone channeling therapy work into his art form, the emotional crux of which is a real life relationship with a spouse. The best of these examples have a propensity for weaving layer upon layer often coming across as esoteric or worse impenetrable--meaning lost on many (worse when you decide to take a fan cut of something set thematically to a song that has almost nothing to do with what’s actually transpiring on screen--but Linkin Park nailed the gravitas, no?) What we’ve ended up with is a work truly and deeply inspired by a serious depressive episode in an artists life. It’s almost a completely different story being told first half to second half (the tone and the focus having shifted to the deepest darkest and most fundamental places about human existence).

What do you do in therapy? (I keep coming back to the way Richard Grannon described it.) You take trauma and you transform it into pure gold. You perform “alchemy”. To process and integrate, the opposite of shunt and dissociate. All of the episodes (original and director’s cut) leading up to 25 and 26 focus in on each of the main characters. Those final episodes, 25 and 26, play out completely decoupled from the plot that had been building up to that point. Some cited budgetary problems or other things. Production was anything but smooth (especially when you consider the state of the author). But all in all despite being a massively anti-climactic let down in most ways, it played out like a therapy session--surrealist trip into the minds of each of the characters all taking turns in “the chair”.

Hope was the theme--the moral of the story in its most distilled and basic form. When they went back, after public reception to this ending was less than satisfactory, they retold 25 and 26 on the silver screen but reattached to the fictional events that the story had been building up to, before this point. The result was an utterly mind blowing finale which was by every measure a critical and commercial success. Hope was still the moral of the story--the future is unwritten.

There is far far far too much to unpack. I’m still finding examples to this day of this show’s influence and lasting impact far beyond anime itself. I could never address here all the things its been to the numbers of people that were impacted by it. They were even going to give it a Hollywood treatment starring Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter) were it not for licensing and corporate studio legal controversy. I’m, in most ways, glad they didn’t, however, given Hollywood’s priorities and propensity for terrible adaptations, but my point is that this isn’t (as you paint it) some obscure work by and for deranged and disturbed individuals. It’s a lauded work of art held in the highest esteem. But it’s also brutally honest, but it would seem that one of these statements usually follows the other. The most impactful and meaningful art is more often than not the art that can be said to be the most unfiltered and honest--raw and genuine.

The future is unwritten. They switched places. In terms of the characters, it was the first real, honest moment either of them had had with each other. It was poetic. It was symbolic. In blurring the lines between art and real life, a bad translation almost ruins this ending. Her next words to him then, read as “disgusting”, should read instead as an expression of “morning sickness” instead of one final fuck you. It’s not even delivered in voice inflection (subs not dubs, people) with the same caustic bite that usually accompanies her usual condescending attitude toward him especially over matters of vulnerability. It would be just like her to find such vulnerability to be pathetic and loathsome. But that’s not what’s happening in this moment. They’ve switched places. One simple touch, in what is the first real, honest moment either of them have had with each other, and he melts. Another heavy moment of silence after looking at him [an image actually replicated in FLCL btw ep.6 he melts] she says, “(you’re) Disgusting / (you disgust me) I feel sick”. “I, myself” said blankly and soberly as originally voiced ...The message here as though to illustrate this statement ...”and life goes on“. Life moves inexorably onward--pulled--moving--with or without you--whether you’re ready or not. A baby. How many rocky marriages, and then a baby...? It’s almost to make trivial the shit they’ve ever fought about. Shit just got real. A baby. ...and life goes on.

The future is unwritten. This isn’t the end; it’s the beginning.

[picture proof FLCL and Eva side by side climaxes to follow... or you know, just refer to your dragnet “screen captures” if you don’t believe me.

As much as I might of my own accord have ever mused about these things, putting out fires you intentionally start whose real consequences drain the life out of me, from you invading my personal space and using whatever you can get your hands on therein to start shit ...the mental and emotional cost to me is beyond taxing in every respect. My every breath, shouldn’t have to answer to you. We’ll go round this block again soon enough, but frankly I just don’t have the time or the energy to waste putting out fires that have absolutely nothing to do with me or anything real but whose cost I am made to bear anyway.

I can’t live “this” way.]

0 notes

Text

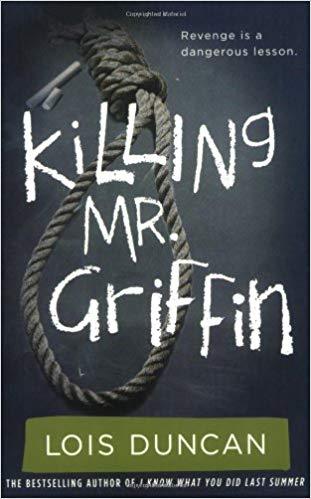

Killing Mr. Griffin by Lois Duncan

High school teachers can be too demanding, especially Mr. Griffin. Fed up with him, a group of kids plan a kidnapping prank, but everything goes wrong when Mr. Griffin winds up dead.

Quick Information

price: $9.00

number of pages: 272

ISBN: 978-0316099004

publisher and date: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers; Revised edition 2010

author’s website: https://loisduncan.arquettes.com

genre: juvenile fiction, mystery

main subjects: mystery and detective stories

Plot

After another hard day with Mr. Griffin, the strictest teacher at their high school, a couple of students plan to scare their teacher into being more forgiving to their students. With Mark Kenney in the lead, they plan to kidnap and frighten Mr. Griffin, then return him to the safety of his normal life with something to make him second guess being so mean to students. However, in order to make this work, they need a few more people, so they enlist Susan, a smart but lonely girl with a huge crush on the senior class president who also agreed to be in on the prank. With all of them set with their roles, some perhaps a bit more reluctant than others, they kidnap Mr. Griffin, but their plan goes south when something happens, and when they go back to check on their teacher who should be just fine, he is dead. The kids have to figure out what to do with their prank gone awry.

Who’s reading it?

Written on a 9th grade level, ages from 12 and up may be interested in the content of the book.

Why did I read it?

In all reality, I was a middle school student scanning the shelves of my school library for my next book to read when I came across Killing Mr. Griffin, written by the same author who wrote I Know What You Did Last Summer and Gallows Hill. Though I admit that I do not remember much of the latter, the former had intrigued me enough to keep reading more of Duncan’s works. The cover of Killing Mr. Griffin at the time that I read it was not the modern one with the noose behind the large and eerie words but two feet tied up in a way only a man laying on the ground could be. The picture was in black and white, almost a sepia color, and the title had a green stripe behind it. The cover was striking, especially when considering that I found it in my middle school library. At the time, I did not read the backs of books, plots, summaries, or even first pages or chapters to determine whether or not I wanted to read a book. I just read them. If only we could be as unprejudiced as we were when we were children. However, since then, I have reread the book, not only because it made such a good impression on me when I first read it, but also because it had a story that was appealing even after so many years. A couple of kids get mad at their teacher for being so mean and grading so harshly so they decide to do what they think is a harmless prank: blind fold and tie him up, smack him around a little, and leave him in the dark and cold for a couple of hours until he breaks and then let him go. But that does not happen, and these children have to deal with the consequences of their actions.

Evaluation

This novel shows how good, honest people can be roped into doing terrible things. Susan is a straight-A student, sweet, always the good girl, and she agrees to participate in an outrageous plan because the boy on which she has a crush asks her to and her part is only doing something that she would already do. All she has to do is keep Mr. Griffin after school long enough for the rest of the students and staff to leave so that the other kids can do the kidnapping. She feels as though she is finally part of a group, has friends, and will maybe start to turn her life around to a happier and more positive way other than just doing well on tests and assignments. She does not want to go through with this plan, regrets it before, while, and after she has done it, and tries her hardest to set what they did right.

The novel also switches between several perspectives, showing the different reactions to the same situation and getting a more complete story. Though the novel mainly focuses on Susan and David, the readers have the chance to see some of the workings to the other characters so that they better understand their actions.

The story is also a cautionary tale that describes what can happen when things get out of control. This is a worst case scenario from a plan that can only have bad endings. The characters have their own motives and views on what this prank is supposed to be, and none of them quite understand the gravity of their situation until it drops on them with full force.

The Issues

Violence / Murder by Minors

Mental illness

Manipulation

Teenagers kidnap, torture, and inadvertently kill their teacher. They leave him in the cold and away from his medicine that he needs for his heart condition. Though they may not have meant to cause his death, they did mean to kidnap and scare him. Their actions were purposeful and in some cases malicious.

The leader of their group is Mark Kenney who has a personality disorder, psychopathy, where he is charismatic and fully capable of manipulating others into doing exactly what he wanted. He makes the other teenagers want to commit this crime by calling it a prank with a motive that has their best interests in mind. He tells them what they want to hear, because he knows what will make them do what he needs.

So why should we read it?

The novel shows different perspectives of the same situation. Not many novels get into the heads of characters who are not the immediate main characters of a story, and yet this one does with the purpose of allowing the readers a fuller view of not only what happened and why but how it is affecting everyone, not just those main people. The readers see the teacher and his wife for a brief moment before the attack so that they can better understand the teacher’s personality and motives as well as the wife’s when she comes back into the story later. David’s grandmother gets a section to describe her feelings about the situation, and how she misinterpreted her grandson’s actions. We see Susan, David, Mark, Betsy, and Jeff - and occasionally their parents - which shows a whole different side to the story that the audience may never have considered had the story been left to only be in one point of view.

How can we use it?

All of these extra points of view help readers relate to what is happening. They need to see how actions affect everyone, not just them or those immediately around them. They need to see that doing something that they may not see as a big deal can become a big deal. This book does a great job at showing how skewed perceptions can be, especially by those of young adults who are still at an impressionable age. They are learning to understand when they are being manipulated, when they are wrong, when they are right, and when they should trust themselves and people who are trustworthy. They also need to learn that sometimes they cannot do anything to stop what has already happened. These children were manipulated by someone who fed them lies of comfort and reassurances to keep them going, but they could not have known the extent of what they were doing. Do we excuse their behavior? No. They still participated in the kidnapping of their teacher which led to his eventual death, but they were coerced and heavily guided by a strong force. Sometimes people are led astray, and they have to figure out how to fix the wrongs before they become worse.

Booktalk Ideas

Mark successfully manipulates several other teenagers into doing exactly what he wants. He talks them into believing that this is what Mr. Griffin needs and deserves. He justifies the actions, tells them plans for if something goes wrong, and makes them believe that he will take care of any issues. How is he able to do all of this so well, even with people he barely knows? Is it his psychopathy that allows him to understand and read other people so well?

Susan does not fit in with the crowd. She is a smart girl who keeps to herself and does not do anything that could be considered wrong or rebellious. The only reason she agrees to the plan is because David asks her and she has a crush on him. However, she is hesitant to say yes even then. Can extreme feelings such as having a crush makes someone’s judgement that blurred? Why is she so easily swayed?

What else can I read?

We All Fall Down by Robert Cormier

I Know What You Did Last Summer by Lois Duncan

Athletic Shorts by Chris Crutcher

Awards and Lists

ALA Best Book for Young Adults--l976

Massachusetts Children's Book Award--l982

Alabama Young Readers Choice Award--l982-83 86-87

Nominated for California Young Readers Award--l982

Selected for Librarians Best Book List, England--l986

New York Times "Best Book for Children"--l988

NBC Movie of the Week -- 1997

Nominated for Edgar Allan Poe Award

Professional Review

Teri S. Lesesne, G. Kylene Beers, and Lois Buckman (1996), Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy - https://www-jstor-org.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/stable/40013439?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents

0 notes

Text

Conditions for Memory: on Lamia Joreige

In Lamia Joreige’s film Embrace (2004), two figures pull at one another’s arms, moving on and off the grainy screen. Behind the figures cars race past in front of a warehouse. Bathed in red light that comes from the road it is hard to see the blue evening sky hanging over the sea in the distance. In this clip what is actually happening is unclear; with every movement what the figures are doing can be reread, reinterpreted, reimagined. Uncertainty is often at the crux at Joreige’s work, and points towards the deeper issues of constructing stable narratives surrounding the history of Lebanon and it’s capital Beirut, the city that forms the setting for Embrace, and home of Joreige.

Born in 1972, Joreige studied film and painting at Rhode Island School of Design, graduating in 1995. Her films, writing and installations traverse the problematic histories of Lebanon, and the relationship between personal recollection and collective cultural/historical memory. Often taking Beirut as the subject, Joreige explores museums, people’s personal memories, and longer histories, to help offer new perspectives on Lebanon’s past and in particular the Lebanese Wars (1975-1990), that saw different sectarian and political groups clash. Often other countries such as Israel and Syria supported these groups, and the conflict acted as means for outside forces to fight their own battles. The Lebanese Wars have left a lasting impact on the country. Between gaining independence from France in 1943 and the 1970s, Lebanon was seen as an example of post-colonial success, but the 15 years of conflict left economic difficulty, political uncertainty, population displacement, militia groups and religious tension, as well as thousands dead, missing and handicapped.

It is these difficulties that Joreige traverses through challenging the orthodoxy of certain histories, and documenting the personal, even if, at times, trying to understand the past shifts beyond fact and into fiction; a poetic act that challenges the past, but exemplifies how, “in the middle of tales of conquest and defeat that shaped (and disfigured) Beirut, one wonders amidst narratives that point out to the impossibility of constructing a good history”.

Andrew Downey states that, “working with archives has become an apparently dominant aesthetic strategy for contemporary artists engaged with the heterogeneity of cultural production across the Middle East”. These artists include Hadji Thomas and Khali Joreige, Abdullah Farah, Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari, as well as Lamia Joreige. Arguably this turn relates to the fetishization of the archive as a place that plays a role in the production of knowledge. For Derrida the Greek route of the word archive, arkhē, means commencement and commandment. The archive becomes a place of origin through domiciliation and consignment of documents, creating a single body of information, that projects power and consequently is used as a referent or base for knowledge. The archive as taxonomy and classification system could also be understood as one possible historical form. Foucault describes this as historical a priori which creates “a condition of reality for statements” but not “a condition of validity for judgements”, and it is on this possibility for alternate judgements that artists such as Joreige address and challenge the assigned power of archives.

In Underwriting Beirut Mathaf (2013) Joreige elucidates the authority ascribed to the National Museum of Beirut due to its institutional power, and the validity of the histories it presents. Mathaf is the Arabic word for museum, and the area of Beirut which is home to the National Museum. It also sits on the now extinct Green demarcation line, which during the Lebanese War marked the border between East and West Beirut and resultantly was a point of conflict that saw kidnappings and shootings.

The Lebanese War saw objects looted, destroyed and taken from the museum leading to a collection that is lacking. Yet establishing what was taken, destroyed or put onto the art market is difficult, as the museum had no comprehensive records of its collection prior to the Lebanese War. It is also hard to establish what the museum does and doesn’t hold, beyond issues of what was and wasn’t lost, due to the barriers put up to individuals such as Joreige:

For various reasons – political and non-political, rational and irrational, and mainly practical because of the museum’s organization and shortage of staff – it has proven impossible for me to access the museum’s post-war inventory, storage, archive of documents and photographs, and library publications including the museum’s bulletin.

When working on Underwriting Beirut Mathaf, the individual in charge of the Museum’s archive informed Joreige that she could only look at what was in the galleries. In response to the museum’s policies, in December 2012 Joreige photographed as many objects as possible that were on display in the museum. Later, compiling all the object captions into one image Joreige created a testament to what impression a visitor to the Museum would gain of Lebanon and Lebanese identity, but only in the month of December 2012. As the objects on display in the Museum will change – being moved in and out of the inaccessible store – so too will the visitor’s impression of Lebanon’s history. By showing the loss of objects, and the possibility of fragile judgements from museums, Underwriting Beirut leaves open questions about what is learnt from archives, but also questions relating to access and structure: the formulation of historical a priori itself.

However the critique is not meant to end with the institution. Hal Foster’s assertion that artists who work with archives are less concerned with critiques of representational totality and institutional integrity, and instead wish to move beyond the archive itself as focus, is true of Joreige. Trying to access the archive of the National Museum of Beirut turned into an institutional critique, but Joreige also wishes to challenge the historical narratives that, although may have their physical home in archives, exist away from institutions.

Just as the archive is shown to be a construct, and a changing one at that, Joreige also shows how histories outside of the archive are illusory and malleable in Beirut, Autopsy of a City (2010). Divided into three chapters, the multimedia installation alters the relationship between the city and history. Joreige believes that the Lebanese War disrupted Beirut’s relationship with history, a fact that is present in Underwriting Beirut, but an issue which Beirut, Autopsy of a City considers through a much longer historical time frame. Joreige discovered that long before the Lebanese War, Beirut had been destroyed and rebuilt over and over. This may not be surprising for the capital of a country that was established in 1920, yet it is a history that in Joreige’s eyes has fallen into darkness due to Lebanon’s very recent history of violence. By assembling different historical records and installing them in a superficial timeline the first chapter of Beirut, Autopsy of a City reveals Beirut’s tumultuous past. But it also draws out new associations and relationships between the ancient and modern shifting the work of the archaeologist into that of a poet, challenging accepted forms of historiography whilst revealing what Foster describes as an archival impulse, the desire to look back and make the past current again through its rereading and new presentation.

The second chapter of Beirut, Autopsy of a City, titled Beirut, 1001, is a video projection that steps beyond juxtapositions of historical documents, and uses a collage of photographs to create fiction. The film shows the transition of Beirut from a small town to a modern city. It starts with the old town in the foreground, looking out over the sea. Boats float in the harbour as gradually new buildings appear, taking the place of the old. Mountains emerge in the background and we begin to see the long stretched curve of Beirut’s seafront. Buildings continue to rise in the distance and old streets give way to modernist towers. Fog falls over the scene and all that is visible is a jetty protruding out into the ocean, but silhouetted against the hazy sky are helicopters, and then warplanes flying over the city in formation, until the whole scene disappears in cloud. At one moment the video shows a ship from the 19th century, a sky from the 1980s and a sea from the 1950s. The Beirut shown never existed at one moment in time, but Beirut’s past is shown through amalgam and allegory. The third chapter turns to Beirut’s future, doing away with historical pictures and documents and moving into an entirely fictive scene. Titled Beirut 2058 all that is left is the coastline, raising the question of how Beirut, a city with a history of erasure and conflict, will fair in the future.

Creating fictions from history echoes Downey’s assertion that the gaps in archives – allow a ‘productive aperture’ that lets the artist imagine. Instead of the artist producing verifiable knowledge, in its place there are suggestions of what could have been, what could have happened. Artists such as Joreige are therefore dealing with a caesura in historical knowledge, but often more is done than simply returning to historical material to offer ideas about what could have filed the gaps that now exist, addressing issues concerning the historical a priori, or imagining the future.

At times Joreige’s work reflects Jacques Rancière’s ideas of ‘the aesthetic age’. Rancière argues this is where the fictive and poetic have begun to merge with the ‘empirical’ that is seen to constitute historical truth, forming a new regime of meaning that challenges History and blurs the logic of fact. This is arguably present in Beirut, Autopsy of a City but the fictive there is clearly distinct from records of the past. We know that the Beirut 1001 is an amalgamation of images and we know that the future of Beirut has not happened. Instead Rancière’s question of whether fact has allied with fiction to form new regimes of truth, or parafictions, is best seen where the question of ‘did this happen?’ is near unanswerable.

Here and Perhaps Elsewhere presents the different stories of several involved with a shooting across Beirut’s demarcation line in 1986. We are given the testimonies of Ziad, the sniper; Oumna, who Wahid Sale – the victim – came to after the shooting, and Oumna’s friend; Nabil, a militia man, who was stationed on the demarcation line the day Sale was shot; and a woman who bore witness to Sale’s death. In this fiction all recounts are told to a detective who is investigating the death a year later. The testimonies are illustrated with photographs from Beirut illuminating the characters backstories, and images from the streets show where the event took place and look as if they are from the time of the shooting, leading to an eerie feeling that even if this is fictive something like Here and Perhaps Elsewhere happened anyway as we are aware of the history of Beirut and the Green demarcation line.

Rancière pushes the coming together of writing stories and writing histories into a political frame, arguing that art operating in this manner is operating like politics. Both are “material rearrangements of signs and images, relationships between what is seen and what is said, between what is done and what can be done”. Art such as Here and Perhaps Elsewhere is also politicised as it causes disruption to the histories and systems of classification held by people in positions of power. Rancière argues that art acting in this manner opens up space for deviation, for thinking away from the conditions they are in. This may be an important factor for art addressing the Lebanese War, as Joreige acknowledges the reluctancy to talk about the past from factions of the general public in Beirut, and how “many of the ‘actors’ of the war are still ‘acting’ today in our current political realm”.

The Atlas Group Archive operates in a similar manner to Here and Perhaps Elsewhere. Created By Walid Raad in 1999, The Atlas Group is an imaginary foundation that aims to document the history of Lebanon through compiling archival photographs into fictive amalgamations and presenting them in exhibitions. The foundation also refers to experts such as Fadl Fakhouri the ‘foremost historian of the Lebanese civil wars’, and individuals like Souheil Bachar who was held hostage from 1983-1993 in Lebanon, however both are fictional characters played by actors. Like Joreige, Walid’s project highlights the power of combining fiction and fact, and it too facilitates new modes of thinking and deviating from systems of classification and held histories through images and testimony. But unlike Walid, Joreige also stimulates this opening up of memory and space for new thought through a different means, revealing how the conditions for memory, and the departure points for readdressing history, are not always tied to institutions (imaginary or real), dependent on the creation of fictions, or created through photography (a medium that is often turned to by an array of artists working with archives in the Middle East), but are in fact present in personal belongings, in the things people hold with their hands.

Objects of War (2000- 2006) is a series of films that ask people to talk about an object they have from the Lebanese War. The second in the series starts with the camera focusing on a woman sitting in front of a red wall. She holds up what is left of her old ID and explains that it is still with her in Berlin where she lives now, but part of it was lost on the 8th July 1982. Putting the flimsy document down, the camera pans up and she shakes her head correcting herself. The subtitles read, “No, the 8th June”.

Just before the 1982 Israeli invasion into Lebanon she was in Shemlan, where her family used to go on holiday in the summer. She explains to the camera that they had heard Israeli forces were coming towards Shemlan from Beirut, where the conflict had started, so they hid in a monastery alongside villagers and other tourists.

“It was very chaotic. I remember there was so much chaos”. She pauses and smiles. “In the monastery… One could hear from one side, the women, reciting the Koran. And from the other room, women, reciting the Gospels”. She tries to recollect the name of a senior figure from the village but can’t – he was the person who directed the soldiers towards the monastery.

“The strange thing for me was that it was the first time I had seen an Israeli. No one had ever imagined, in ’82, that Israel could enter. It was the first time in my life that I felt hatred”. Hatred at the occupation, hatred at the bullets fired into the walls to terrorize who was hidden inside. But she realised, when confronted by a young Israeli soldier, who looked no older than 20, that he too had a face, and that he too was a human being standing there in the same room as her. Looking back to the monastery through her ID, her eyes well and she laughs, struggling with what Joreige describes as the “paradoxical feeling of hatred but humanity at the same time”.

The ID turns into a mnemonic, bringing back a series of experiences that otherwise would have remained hidden or repressed. Proust asserts in Remembrance of Things Past that “The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) of which we have no inkling”. Of course, Joreige’s subjects have chosen their objects for discussion, but the revelation of humanity in conflict evokes the power objects hold for recollection that Proust describes. In Objects of War the testimonies are also resolutely political in that they test official accounts of the Lebanese War’s history by drawing from the personal, whilst set within the bounds of the more wider known past such as the Israeli invasion and splits between Religious groups. Consequently the possessions talked about and through in Objects of War reveal the power and complexity of memory: tied up, formed, somewhere between personal experience and collective memory.

It is Joreige’s work that focuses on the personal in war and conflict that offers the most potential for testing knowledge, and as a record and archive itself, like the archives she has turned to in other work, it will act as testament to a time and moment, creating not a utopian end through research and discovery that Foster argues is the aim of archive based art practice, but instead a heterotopia: varied points of departure for those in the future to turn to and conduct their own process of reinterpretation and understanding. Derrida argues in this vein stating that the archive, which we have seen manifested as institutional, artistic and personal, “is a question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow.

Yet the two figures jostling back and forward, even in their uncertainty, point at something beyond the difficulties and blind alleys that history and the future force us to face, and to memories of another kind. They point at the people who are at the centre of these stories, who live lives in terror, tragedy, conflict, war, and political struggle, but are also living away from it, even if for a moment in the early evening with street lights blazing. We like to imagine they’re dancing. We hope they embrace.

0 notes

Text

Us and Them and You and Me

The Lord of the Flies novel by William Golding poses some very interesting questions about the alarming possibility of resorting to barbarism in an uncivilised and unsupervised environment. He sheds light on the possibility of violence ensuing because of acquiring and maintaining power. Several aspects of the book, along with psychological analyses, can be compared to the cruelties of the world we live in: racial separation, segregation and discrimination – the division of people into groups that leads to prejudice and/or causes discrimination against another ‘type’ of person also sectioned off by the ‘other’ dichotomy; The Abu Ghraib prisoners tortured and abused by American military forces - atrocities caused by a corruption of power, and the belief that their actions wouldn’t need repercussions. Once again I find myself wondering about the lengths humans would go to in the name of survival and power. I wondered if the fictional work by Golding has certain truthful concepts that can be related to, and can be exemplified by, our current era. My question was answered. It can indeed.

The route of prejudice can be linked to the ways in which individuals self-identify. Self-identification is not something that can be accomplished by ourselves. It is largely to do with our environment, our role models, and the friends we believe we can, or do, identify with. The social identity theory therefore, assumes that ‘prejudice can be explained by our tendency to identify ourselves as part of a group and to classify other people as either within or outside that group.’ (Jarvis, Russell and Gorman, 2004, p22). In Lord of the Flies, the fundamental cause of their rivalry and competitiveness is through their sectioning off into groups. Ralph is chosen by the large group of boys as the leader, he then appoints Jack as the leader of the hunters. What was meant to be an efficient strategy for the survival of the entire group of boys – like the maintaining of the signal fire and hunting for food – turns into something warped and morally questionable. Experiments have been carried out to see the effects of classifying people into groups: it was frequently discovered that the categorisations caused comparisons which led to ‘in-group favouritism’ (Jarvis, Russell and Gorman, 2004, p24). When tying the in-group and out-group dichotomies to nationality (also relatable to race), the experiment (in the form of a questionnaire) by Poppe and Linssen (1999) showed that ‘Eastern Europeans tended to favour their own nationality over those of other Eastern Europeans but not over Western Europeans’. (Jarvis, Russell and Gorman, 2004, p23)

However, the inter-group favouritism was not to last in The Lord of the Flies when the boys from Ralph’s group leave to join Jack’s band of hunters. Why was this exactly? Why did the boys not prefer Ralph’s more gentle and more rational approach to leadership? By this point, Jack had proven his capability for hunting and killing the pig. Being the kids that they are, they’re mostly interested in having fun – Jack’s hunting, spear-wielding, blood thirsty party gives the boys the euphoric thrill of providing for themselves. Ralph on the other hand is more focused on the more environmentally useful, and consequently, less appealing aspects of survival. The realistic conflict theory states that prejudices and group conflict occurs because of competition between groups for resources desired by all. Ralph wanted the groups to work together and share primary resources (e.g. food), but because Jack makes the desire for meat accessible in his group, the boys from Ralph’s group were more inclined to join him. The violence that erupted between the boys and their two groups in the Lord of the Flies plot freakishly resembles a field experiment that was praised for its high ecological validity because it wasn’t executed in a controlled environment. The ‘Robber’s Cave’ experiment by Sherif (1954, 1958 and 1961) showed the prejudices, the moral discrepancies and the violence that can erupt between groups of boys in different teams and in competition with the other team: the results show that the boys in separate teams started off just being verbally abusive towards the other team, but eventually got so aggressive with each other that the researchers needed to physically intervene.

Yet another question arises, which is, why did Jack have the need to be in charge; why was his need to be the supreme leader of the boys so important to him that he was willing to kill to get it? It could be because they are children without any adult supervision, and yet it could be because of an innate willingness to outmatch, rival and conquer the individual in a higher position. The authoritarian personality theory tries to explain why some people are more prone to prejudice than other individuals. ‘It is characterised by… hostility, rigid morality, strong racial in-group favouritism (ethnocentrism) and intolerance of challenges to authority…’ (Jarvis, Russell and Gorman, 2004, p24) This theory therefore, offers us a reason for the totalitarianism and ethnocentrism we can recognise in previous leaders like Hitler. Individuals like this will get the need to enforce their power over the other, much like Jack does to the boys in Lord of the Flies – to the point where he needs to eradicate the leader of another group to prove that his power is absolute. The ugly reality of the corrupting influence power has over some people is proven by the American soldiers in charge of the Abu Ghraib prisoners. Via the publication of photographs and videos, the behaviour of the US soldiers who were abusing naked Iraqis became public knowledge that repulsed all that saw it. One soldier was sentenced to eight years for sexually and physically abusing detainees. Another admitted to carrying out a mock electrocution of a captive at the prison. There is speculation that the soldiers needed to carry out certain measures of aggression because they were commanded to do so by the US command that required them to gather some intelligence from the prisoners (Russell and Jarvis, 2008, p23). Thus, the lines for the right and the wrong method of interrogation became blurred; the soldiers exercised their power over the helpless prisoners, and their attempts at relinquishing information from them became warped – and further fuelled by their power trip.

The many factors that can cause humans to resort to barbarism seems to be disturbingly easy to fall into – depending on the kind of person you are, the kind of situation you’re in and the type of group you identify and feel safe with. It also appears to be caused by an escalating situation arising from prejudice – the catalyst perhaps being the desire to acquire resources for the people you identify with, and the competitiveness that arises from wanting to triumph over the other group. Power can also be the catalyst that causes one to suspend moral codes in favour of acquiring, or maintaining, their positon. The Lord of the Flies (a pig’s head on a spike surrounded by swarm of flies) says ‘Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill!’ ominously adding, ‘I’m part of you…’ We need to ask ourselves: Is this Beast part of all of us? Is there a circumstance in which we would let it out? Most likely, none of us would like to know the answer to these questions.

*All references are hyperlinked*

0 notes