#which is bizarre because they created the sci team because they wanted to throw in more characters to write for

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the old lost fandom fucking loathed charlotte so i really really like how the new lost fandom likes her and respects her way more than the writers did and we’ve like really made her our own, ya know?

#if i come across as really defensive about liking charlotte it's because#she's a very underwritten and poorly handled character and i feel like people are gonna like attack me for liking her?#but nobody ever does because like you guys are nice and im nice. and i guess like my sincerity wins out also#rebecca mader is a GREAT actress and they really underused her talents#so i like the charlotte in my head mostly? the charlotte that could've been#this loud passionate outspoken nerd who has a silly laugh and loves star trek and chocolate#and loves daniel faraday with all of her heart#and i feel sheepish because she isn't... much in the show ya know...#i partly blame the writers strike but also the lost writers just didn't. care enough#which is bizarre because they created the sci team because they wanted to throw in more characters to write for#you guys are cool. like nobody dunks on me for how i treat characters. thats neat

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

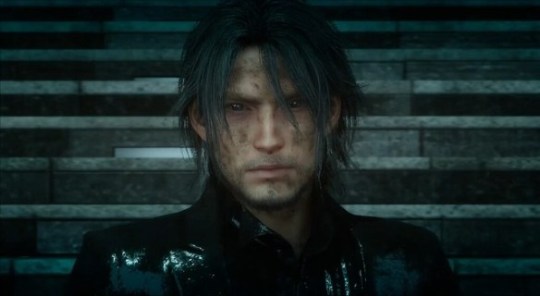

ScottyMcGeester Plays Every Final Fantasy Game*

*Okay, all the main games except 11 and 14 since they are online only, and also no spinoffs or sequels.

THE INTRODUCTION

Years ago, I had a goal to finish every Final Fantasy game. As of December 30, 2020, I finally reached that goal. I originally started posting these reviews way back in 2017 on VGF(VIdeo Game Forums), and posted one review after another as I completed each game. I had already finished a few before I started reviewing the series, such as Final Fantasy I, II, VI, IX, and X.

Final Fantasy X was my very first Final Fantasy game, way back when it first came out on the PS2. It took me years to finish that game, mostly because I was still a novice at RPGs and I didn’t quite know what I was doing. Still, the world and concepts of Final Fantasy gripped me. As a sci-fi/fantasy writer, they inspired tons of elements in my stories. The series spans a multitude of genre-bending stories – sci-fi, fantasy, some steampunk, modern fantasy, space, traditional fantasy with knights in armor – and a whole lot of crystals. I wrote these reviews as if you have no idea what Final Fantasy is – whether you are a gamer or non-gamer. This first post is a general introduction to the series as a whole, but even if you are a die-hard fan already, there are some things that I explore that I hope you'll find interesting. What is Final Fantasy? Final Fantasy is a roleplay video game series that started back in 1987. The first game was reminiscent of Dungeons and Dragons, where you could choose one of six roles for a team of four: White Mage, Black Mage, Red Mage, Thief, Monk and Warrior. Square, now known as Square Enix, developed the game. A legendary rumor about the title “Final Fantasy” comes from the story that they were on the verge of bankruptcy. They only had money for one more game, a fantasy game. They dubbed it “Final Fantasy.” This apocryphal story is nowhere near true. Square had made video games before and they didn’t do well, but the company itself wasn’t on the verge of bankruptcy. What happened was that the developer, Hironobu Sakaguchi, had planned to retire. He didn’t see any foreseeable future in video gaming with Square’s mediocre performance. He wanted to make a fantasy game and dubbed it “Final Fantasy”, since it was to be his personal last work. He also wanted the game to be abbreviated as “FF” – they originally had “Fighting Fantasy” in mind but that name was already trademarked by a board game. Final Fantasy initially sold 400,000 copies in Japan and became and instant hit. Nintendo of America approached Square to release a localized version for the states. Final Fantasy became far from Sakaguchi’s last game. What’s Final Fantasy about? Every main Final Fantasy game has a new story with new characters and even new gameplay. Some games have direct sequels and are recognizable with a subtitle, or an additional number following a dash. For example, there is Final Fantasy VII, and the direct sequel to that Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII. There's a direct sequel to Final Fantasy X titled Final Fantasy X-2. But even though each Final Fantasy game is different, there are still central elements that make them a Final Fantasy game. You can’t just write up a random fantasy story and slap the Final Fantasy name on it. The following elements are what make a Final Fantasy game. Some are obvious while others not so much. Chocobos:

Chocobos were first introduced in Final Fantasy II, but have been present ever since. They are cute, large birds that the characters often ride across fields or sometimes call into battle. They have practically become the mascot of the series. Moogles, Cactuars and Tonberries – oh my!

Moogles (pictured above) are telepathic creatures that help the players, or sometimes they can be a playable character. They debuted in Final Fantasy III.

Cactuars (right) and Tonberries (left) are cute, unassuming enemies that are actually highly dangerous, killing you in one shot if you are not careful or fast enough. The former debuted in Final Fantasy VI while the latter debuted in Final Fantasy V. Summons:

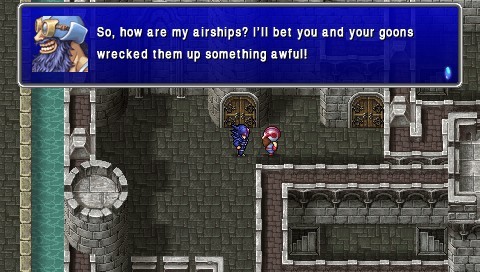

Sometimes they go by different names, like eidolons or espers. Summons are massive, fantastic beasts that you can call upon to aide you in battle to fight the enemy. Summons became a staple ever since Final Fantasy III. In some games, they are merely there to call into battle, while in other games they are central to the story. Airships:

Airships have been present since the first game. They are massive boat-looking airplanes. In the more recent games, airships look almost like spaceships.

Cid:

With the exception of the original Final Fantasy (except in later remakes), every game has a character named Cid. Cid is typically the character who owns an airship.

Items and Magic Spells:

Each game shares virtually all the same items and magic spells. Antidotes. Eye drops. Maiden's kiss. Holy water. Phoenix Down is well-known for reviving knocked-out characters in battle. The spells follow a hierarchy of levels. For example, Cure is the basic spell to heal somebody. The second level spell for healing is Cura. Then Curaga. Then finally Curaja. Most other spells follow the same format. The same high-level spells also frequently appear throughout the games, such as Holy and Flare.

Crystals:

With a few exceptions, crystals appear in nearly every game. They often serve as plot devices, whether they be the force that protects the planet or powerful objects coveted by the enemy. They also oftentimes have a consciousness of their own, communicating with the characters and calling them to their destiny.

Mythological References:

Final Fantasy is riddled with mythological references. Many summons and creatures take the names of mythological creatures or deities, such as Shiva, Bahamut, Leviathan, Behemoth, Odin, and Ifrit. Certain villains share the names of mythological figures or they are derived from certain mythological concepts, such as Gilgamesh and Sephiroth. Many of the games have legendary weapons you can find near the end of the journey. These are typically named after legendary Japanese figures, such as Masamune and Yoichi, or other world mythologies, such as Thor’s hammer Mjolnir. Saving the World:

Final Fantasy isn’t about saving a particular princess, or person for that matter. The ultimate goal is to save the entire world, or even the very fabric of reality. Evil spreads in many ways, such as a sealed darkness trying to break free, empires with ambitious goals, villainous subordinates who pull the strings of politics, or empires destroying the environment. Typically, the main cast consists of characters from all walks of life. They all have to learn to work together and get through their personal struggles to save the world. Existential Crisis (or Startling Revelation):

By the time you reach the third act of a Final Fantasy game, some startling revelation forces the characters to question their very existence. A villain is revealed to be a hero’s family member, a main character realizes they're a clone, another realizes that they cannot live without magic, etc. Typically, the main character questions the nature of their soul, if they die like regular beings and become part of some greater life force, or blink out into oblivion. Whatever the revelation may be – it serves as a final crisis that the characters have to overcome. The Descent into Hell:

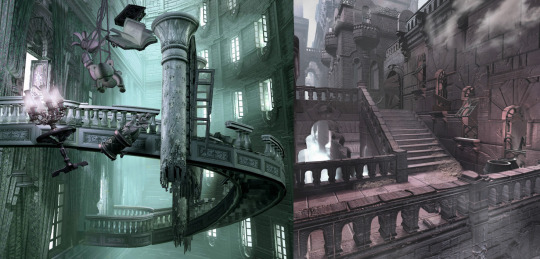

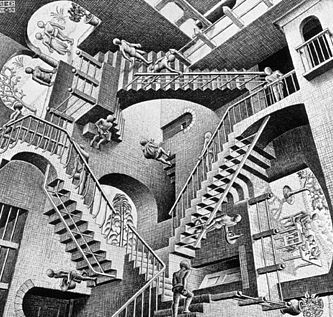

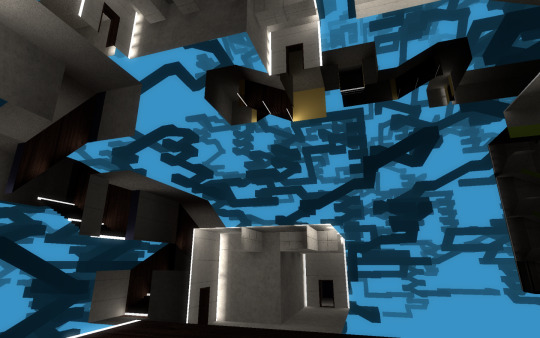

Every third act of a Final Fantasy game ends with what I like to call a “descent into hell”. The final dungeon is always some kind of bizarre world. In Final Fantasy II, you literally descend into hell to fight the Emperor. Throughout the series, hell is more metaphorical. The final dungeons can be a massive, sprawling tower or dreadnought, or a strange dimension that appears to have no rhyme or reason. Sometimes I'm reminded of M.C. Escher’s work, “Relativity”, or sometimes it reminds me of some cosmic horror featured in the Cthulhu Mythos. These final dungeons can be inter-dimensional rifts between space and times, pockets in reality, subterranean depths, insane worlds that the villain created, and worlds of darkness. (Final Fantasy IX's Memoria)

(M.C. Escher's “Relativity”)

These stylistic approaches for the final dungeon represent the oncoming battle with the forces of chaos. Fighting God:

After venturing through the surreal and hellish final dungeon, you face the main villain. The main villain always achieves godlike status or the characters actually have to defeat a god in order to save the world from its oppressive reign. Many stories appear to throw in a last minute ultimate god who was pulling the strings of the plot the entire time. The purpose of dealing with gods and goddesses represents the characters’ desire to control their own fate and alter their destiny. Most of these bosses are strange and grotesque, definitely getting a Cthulhu vibe from them. I looked at them and thought, "Christ, what the hell is THAT supposed to be?"

It always feels like THE final fantasy:

Each game, no matter what happens or how it happens, feels like the be-all-end-all of its story – its fictional universe. Direct sequels were unheard of until Final Fantasy X-2, which while fun, was wildly different in tone from the original game, and critics pointed out that it ruined the finality of Final Fantasy X. This is one reason why I think direct sequels to Final Fantasy games fail – what else could the main characters possibly face that is more dangerous than the one they just encountered? Anything else would feel like child’s play to them. NOTABLE PEOPLE Aside from the characters, stories and games themselves, the people behind the series have achieved legendary status. Nobuo Uematsu:

The original composer of Final Fantasy. Uematsu single-handedly scored the first 9 Final Fantasy games. Uematsu surprisingly never had any formal training in music – a trait that would ostracize any composer, such as Danny Elfman. I find that the those who haven't had any formal training usually break the mold with music. Uematsu started working for Square at around 25 for the first Final Fantasy game, starting out with nothing and never suspecting his job would lead him where he is now. His music is unique for incorporating elements of classic and progressive rock, specifically in the battle themes. Uematsu’s themes for each game have achieved instant recognition in the gaming world, as recognizable as the theme to Star Wars or James Bond. Tetsuya Nomura:

Tetsuya Nomura is a video game designer and director who started at Square in 1990. He rose to prominence when he was given full control of designing the characters for Final Fantasy VII – arguably the most popular Final Fantasy game to date because of its characters: Cloud Strife, Tifa Lockhart, Vincent Valentine and Sephiroth. Nomura went on to create more legendary characters for Final Fantasy VIII, X and XIII. Yoshitaka Amano:

Amano is the artist whose work is most known now in Final Fantasy. He has done concept art and design for every game in the series. His style is instantly recognizable. He has also drawn for many anime shows, comics and mangas, such as Vampire Hunter D and Sandman: The Dream Hunters.

And last but certainly not least - THE MUSIC Final Fantasy has left its mark in the musical soundtrack of video games. Each game more or less shares three of the same memorable tracks.

The Prelude:

youtube

The Victory Fanfare:

youtube

The Final Fantasy Main Theme:

youtube

THE REVIEWS

Each review I post will critique major aspects of each Final Fantasy game, such as its gameplay, graphics, story, and music. Today is currently January 3, 2020 (technically the 4th when I post this because it’s past midnight), and I will be posting one review per day so as to not lose my sanity editing and formatting everything at once here. So look forward to the very first review tomorrow starting with the very first Final Fantasy game.

#final fantasy#final fantasy v#final fantasy vi#final fantasy vii#final fantasy vii remake#final fantasy xv#final fantasy xvi#tifa loc#cloud strife#sephiroth#nobuo uematsu#video games#sony playstation#playstation 5#final fantasy x#onvideogames

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midsommar

Written & Directed by Ari Aster

So you want to be a writer-director. In film school you develop your passion project idea. You work on it, meticulously rewriting every line, every word until it is perfect. You run through it countless times, trying to get the pacing just right. And if you’re lucky, after 10 years of working on it, constantly improving it, your script actually gets picked up and you get to make your film. And it’s a smash hit! So now the studio throws a shitton of cash and tells you to make another one. And you only have two years to get it done. Previous victims of the sophomore slump include Neil Blomkamp following up “District 9” with “Elysium” and Dennis Hopper going from “Easy Rider” to “The Last Movie”. I felt fearful for Ari Aster’s second feature length film was to be released a year after his first, despite “Hereditary” being one of the favorite films of 2018. Seeing “Midsommar”, I felt a different kind of fear.

Mental disorders, anxiety, grief, cults, and rituals are all notable aspects of both of Aster’s films. The similarities between the two are especially prominent in the first act, before the Americans venture to Sweden, but this is not a rehash. Though “Midsommar” does not have any scenes that are as profoundly impactful and gut-wrenching than the accident sequence in “Hereditary”, this film is overall a more complete film. Most noteworthy, is that unlike Aster’s previous film which goes off the rails in a laughable manner in the final act, “Midsommar” manages to drive up the tension and stakes whilst remaining believable. All the laughs – there are a plethora of dark humor moments – are intentional. Toni Collette, as the female lead of “Hereditry”, had a memorable, manic performance, though, understandably, some found it to be over the top and ridiculous. Florence Pugh’s character is much more subdued, but she gives an equally powerful performance. A director is responsible for pulling out the best performances from the actors and Aster has a perfect record thus far.

The setting of the film is a folksy village in Hälsingland, Sweden full of flower children in folk clothing, folk dancing and folk singing and folk everything else-ing. One of the American visitors is quite unnerved by the fact that even at 9 pm, the sun in shining brightly in a bright blue sky. One the surface, it may seem like an animist utopia, but seeing one villager playing a flute as another two are locked in an overly long and intimate embrace, you get the sense that it is all too good to be true. As you spend more time with in the commune, you learn about all their bizarre and disturbing traditions.

Horror, like sci-fi, works best when used as metaphor or allegory and about more than just killing people and scaring the audience. “Hereditary” went a step further and for most of the film is a family drama lacking overt horror elements. There are more traditional horror elements - body horror and gore – throughout “Midsommar”, but it still retains a strong emotional core. A seemingly utopian love-empathy cult is the perfect setting for a break-up movie. Dani is an anxious person who needs a lot emotional support, but her boyfriend, Christian – and with a name like that, should you really be going to pagan villages? – is not as invested in the relationship. Their relationship deteriorates as does the situation in Hälsingland.

Once again, Aster shows how he is a master of unease and tension. The feeling of dread and danger builds slowly over two and half hours. Though at times there might not be a lot going on in the foreground, the cinematography is so wonderful, that the film never drags. Every shot either has something weird going on in the background, or is beautifully composed, or is it simply cool. Characters take psychedelics and the special effects of them experiencing the visual hallucinations – faces being distorted or the breathing trees – is top notch and hypnotizing without going over the top. His depiction of anxiety via Dani is also spot on. The opening shot is of bright summer Swedish nature with folk singing which suddenly cuts to silent winter scene. Aster often uses this technique of edits with sharp visual & aural contrast which stops the audience for getting a proper emotional footing. And of course, there is a perfect creepy horror score that incorporates the local folk songs. There are no jump scares, but meticulously crafted mood.

Ari Aster is a filmmaker to look out for. For a second time he has mastered cult horror and I hope he will branch out and make just as great films in other genres. Hopefully, he teams up once again with cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski, because that duo is something special. A lot of movies are created to be entertainment, which is especially true for the horror genre. “Midsommar” is not just entertaining, it is art.

10/10

IMDB: 7.7 RT: 82% / 61%

0 notes

Text

the belly of an architect

When The Beginner’s Guide was released in late 2015, there was a sense that the current lexicon of video game writing was somehow inadequate to properly describe it. Here was something that was entirely in keeping with every trend in indie games: it was personal, political, metafictional; it was witty and ironic, in the highest sense of those terms; it was a game about games, and it was a game about people. It was also funny, visually inventive, and above all it felt like something genuinely new. It was received with good reviews, tempered with caution. Even players who were affected by it seemed to hold it at arm’s length. Much like the sight of somebody having an emotional breakdown in public, the implication was that it was powered by something that was somehow beyond criticism.

The game had a certain amount in common with The Stanley Parable, the previous work by creator Davey Wreden. Both games are told from the first-person perspective with 3D graphics, and place a very limited range of interactions at the player’s disposal. There is not much to do in these games; you wander alone through a world while an unseen narrator comments on what you’re doing and what you are looking at. Indeed, The Beginner’s Guide is even more limited in this respect than The Stanley Parable — there are none of the alternative paths, hidden endings and secrets that many players found so endearing in the latter title. But both games are full of jokes about the absurdities of game design, and in spite of their sometimes acerbic tone, both are made with a rich empathy for players and designers alike.

Where things differ is in the uneasy relationship of The Beginner’s Guide to reality. It purports to be a set of unfinished games originally created by somebody called Coda. (This requires some suspension of disbelief: we know from the credits that a small team of other people worked on this game as well, but within the fiction of the game, they might as well not exist.)

The story goes that Wreden has spliced fragments of Coda’s creations together into a semi-coherent experience in the hope of demonstrating the work of his talented friend. As the player moves through Coda’s worlds, Davey’s voice is their tour guide. His explanations provide a ‘story’ to what otherwise might seem a totally abstract set of design decisions. But Davey is more than a narrator: he’s the architect of the entire experience, warping the player from one section to the next, and often interfering directly with Coda’s work in order to make it possible to play.

This question of possibility is key to understanding The Beginner’s Guide. For Davey, everything in life seems possible, or can be made so; for Coda, it’s the opposite. Coda was, we are told, a socially awkward person. To borrow a phrase from Sarah Baume, he is ‘not the kind of person who is able to do things’. Yet Coda’s levels seem quite straightforward at first. He dabbles with a map for Counterstrike, and a science fiction thing that almost feels like the start of a ‘real’ game. But even in those early examples, his work demonstrates a tendency to add inexplicable elements which interrupt the experience entirely.

A bizarre bug in the sci fi game means that if the player walks into a laser beam — which they have to do in the absence of other options, even though they know it’ll kill them — they actually end up floating slowly through the ceiling, and then up and out of the map, so that the whole of the crafted space is visible to them. Is this a sort of expressionism, or is it simply a mistake? Why would somebody put something like that in a game? What were they trying to tell us?

The basic situation between Davey and Coda is emblematic of a certain tension present in the way we think about games today. On one side, we have the idea of games as personal expression: the idea that in a game one might be able to turn one’s own experiences into a kind of machine for empathy. On the other, there’s the notion that games don’t need to be ‘about’ anything except their own mechanics: that they should be accessible and rewarding and coherent and, you know, fun. The Beginner’s Guide is an attempt to resolve this tension -- both within a creator’s work, and their life. Is it possible to make a game which is complete, rational and enjoyable, when none of those things are true of life?

The personal approach is Coda’s modus operandi, but his games aren’t expressive in any kind of straightforward way. At times, they have all the cold unreality of conceptual art. And it’s hard to tell how they might be encountered in isolation, since as it stands, they can only be appreciated alongside the insight that Davey provides into their methodology. He’s like the curator of an exhibition who creates an experience by placing one work alongside another, by colouring the backdrop, by writing the cue cards. At every stage we are told what to think about we are seeing. And like any good critic, Davey isn’t hesitant to root around in the guts of Coda’s work if it means he can get his point across better.

(considerable spoilers to follow.)

Davey finds a lot of things to show that were never meant to be seen at all. A distinguishing feature of video games is that a great deal of extra craft can be present in the work itself, but also be totally invisible to the audience, even though it represents a deliberate artistic gesture. Imagine a writer who encoded whole extra passages in a novel by sealing them up within the endpapers: the equivalent of this comes early on in The Beginner’s Guide when Davey strips away the walls of an innocuous hallway to reveal a vast network of interconnected passages floating in the void; an entire hidden labyrinth, forever unreachable by the player.

This is emblematic of the eternal problem for Davey. Coda’s games were never intended to be ‘played’ in the commonly understood sense. Coda created a staircase that would slow the player’s movement speed in proportion to their progress along it, making it almost impossible to ever reach the top. He built a cell within a huge, elaborate prison, where the player had to spend hours and hours in real time before they would be allowed to proceed. In one of his more detailed creations, Coda made a little house in which the player can only repeat a cycle of tedious domestic chores while a nameless companion provides a stream of inanely optimistic chatter. Davey allows the player a taste of all these, but he cuts them short too. For him, the work cannot be allowed to speak for itself: context is king. And who else is there to provide context but Davey?

Over time, Davey begins to build up a portrait of Coda in the player’s mind. These are the creations of a person who is anxious and depressed. This is the work of someone who is subject to a kind of creative paralysis; a sense of crippling inertia which sees him repeating the same small, obsessive routines that have damaged his personal life. In Davey’s version of their relationship, Davey himself only exists as a helpful counterpoint. He tells the player how he encouraged Coda to share his work, and to make it more accessible to a wider audience by toning down some of the more difficult aspects. And eventually, Coda’s creations begin to take on a different shape. Davey is delighted to point out when a clearly defined end point appears in the levels, marked by an old-fashioned lamp post.

But at the same time, things seem to be progressing towards a very uncertain place. In this sense, the ending of The Beginner’s Guide has a certain shape to it reminiscent of Gone Home. Players approach both having worked through a great deal of dark subject matter, much of which suggests that something horrifying might be around the final corner. But instead, the game has one final curveball to throw.

The last world Coda shared with Davey was his most impressive, and his most demanding. An enormous tower that stretches upwards through endless dark space. To approach it, the player has to make it through a maze with invisible walls: touching any wall means death. And even if they manage to get through this, there’s a locked door where the switch is on the other side of the door — it’s simply impossible to open. (As ever, Davey is on hand to warp the player past both of these obstacles, if they choose.)

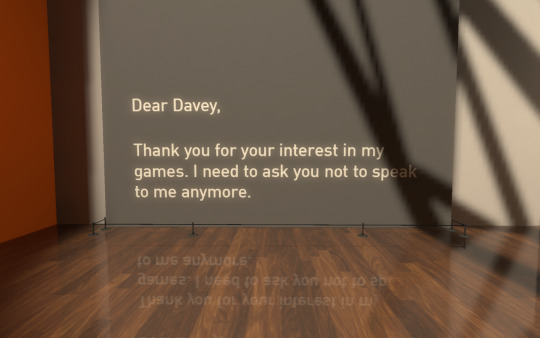

Once the player has passed through every one of Coda’s impossible challenges, they find a gallery, with a series of messages on the walls.

‘Would you stop taking my games and showing them to people against my wishes?’

‘Would you stop changing my games? Stop adding lamp posts to them?’

‘The fact that you think I am frustrated or broken says more about you than about me.’

This, then, is the real story of The Beginner’s Guide. It is a confession of sorts: Davey’s interference with Coda’s work has gone beyond packaging it in an accessible way. He’s adopted it entirely. And as Davey explains, in a rare moment of honesty, he’s come to directly identify with certain aspects of it. Coda’s worlds express something that Davey’s conventional persona cannot talk about. And Davey wanted to share them with the world because the ensuing admiration made him feel valued; but in doing so, he may have destroyed something essential about them.

Perhaps Coda wasn’t a depressed person after all. His messages to Davey seem to suggest as much; or as Davey puts it: ‘Maybe he just likes making prisons’. Depression and anxiety are not generally conducive to creativity, and Coda was nothing if not creative.

But we aren’t quite at the end of the game.

The final sequence is an epilogue. It’s the only part of the game which isn’t framed as Coda’s work.

A train station leads to a windowless train carriage. The train leads to a station outside a stately home, the lofty rooms filled empty but for heaps of sand. More caves, more columns of dark and light. Then we are out into a little empty abstract space of bright yellows and blue skies, a visual tone not dissimilar to Coda’s first map for Counterstrike. And then down a little hole in the ground and we’re in that space ship again from the start of the game. Here again is that laser beam, so strangely broken; what do you think will happen if the player walks into it?

Davey is talking again, but this time from the heart. He’s no longer interpreting, nor commenting on the environment: he’s just telling us how he feels. It’s refreshing, and true. In this moment, what we have suspected all along comes to pass: Davey and Coda have become one and the same.

It’s to the game’s credit that a player might feel uncomfortable at this stage, as though they had accidentally wandered into a personal conflict between two old friends. But nothing happens by accident here, no more than it does in any other video game. The question of whether or not Coda ought to be considered a ‘real person’, so often raised around the release of The Beginner’s Guide, is not without interest; but not for the reasons many people thought. In the reality of the game, Coda is no more or less fictional than Davey Wreden.

The world was always Davey’s, in every sense. Perhaps Coda was only ever a part of him: one that he originally believed he could hold at an arm’s length, but which he eventually comes to embrace. By the time we reach the end, he’s absorbed Coda’s lessons and moved beyond them. He knows that the home is a prison, and that the prison is the maze, and that the maze is a the world. He’s realised that it might be possible to create a thing which is both an entertaining experience and a valid means of personal expression, without necessarily telling the player how to feel about it at every juncture. In other words, he’s ready to create something that looks a lot like The Beginner’s Guide.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 Giant Crazy Real Things That Look Straight Sci Fi, Son

A whole bunch of hardcore science stuff went into designing pretty much anything within your line of vision right now. Why, your smartphone alone took up to three Science to induce. Three! Some of those Sciences were Scienced up in bearing old Science Buildings, sure — but some of them were birthed from bizarre, fantastical landscapes like …

7

The “Russian Woodpecker” Looks Like A Kaiju Wall

In 1976, radio signals around the world were interrupted by a strange, regular, tapping noise over the airwaves that people nicknamed “The Russian Woodpecker.” Nobody knew what it was exactly, but radio geeks eventually managed to triangulate its origin to a place just outside Chernobyl, in Ukraine. Specifically this thing TAGEND Ingmar Runge/ Wiki Commons It was, at the time, the scariest thing anywhere near Chernobyl .

This was before that other incident that made Chernobyl famous, so of course back then it appeared a little … fresher … than it does these days.

Ryan Menezes But it’s holding up pretty well for 40 -year-old untended steel .

Given the supervillain-bent of most massive Soviet projects, and, well … just the looking of that crazy damn thing, supposition was rampant: It was a mind-control device, a climate machine, hell, maybe only a giant antenna to pirate Martian pornography. We weren’t genuinely on speaking words with the Soviets, so it’s not like we could just ask them.

Alexander Blecher, blecher.info It would be decades till Russians occupied and controlled the White House .

After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the Woodpecker maintained tapping for a couple more years and then fell silent. It was merely after the Cold War aimed that we were able to find out what it truly was: The virtually 500 -foot-tall metal wall known as Duga-3 was one of three radar installings capable of seeing incoming American weapons. That’s not as interesting as our wild guess: Giant Gamera fence. But reality so rarely is.

Wow, what a truly amazing structure, rendered virtually instantly obsolete by satellites .

6

The World’s Most Silent Laboratory Look Like Weird Video Game Levels

Want a little peace and quiet? Go to the park. Want all the peace and quiet? Your alternatives are TAGEND

1. The grave, or …

2. An anechoic chamber, like the one at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

Because if there’s one thing we all associate with jet engines, it’s absolute silence .

It looks like aliens holding Air force One for ransom, but that blue spiky padding is just sound- and radar-absorbing polyurethane, which totally shields the inside of the building from outside sound and electromagnetic waves, permitting the Air force to test sensitive radar equipment.

Inside, you hear nothing, other than your own hollering hallucinations .

And this isn’t some bizarre technology limited to the military — scientists all over the world make use of these chambers for testing sensitive voice and radio technology. Eckel Industries has one that looks even more alien TAGEND Are we sure this isn’t a 2001 screen cap ? And, of course, techno-supervillains Apple have furnished 17 of these rooms at a total cost of $ 100 million to test transmitters and general iPhone performance TAGEND

To eradicate audio, they started by removing all headphone jacks .

But if you’re looking for the quietest place on the entire planet, that’s Microsoft’s audio lab in Redmond, Washington TAGEND We don’t hear much activity in Bing headquarters .

It’s so quiet in that room that people can hear their own blood . It’s the only place in the world where instruments was in fact pick up the audio of goddamn molecules brushing against one another. And Microsoft utilizes it pretty much exclusively to prove that they’re better than Apple.

5

California’s Water-Saving Devices Look Like Alien Egg-Spheres

California’s historic drought has necessitated some fairly novel water-conserving technologies. Take, for example, this clutch of gleaming black extraterrestrial eggs infesting Los Angeles’s municipal watering holes.

It looks less gross than most LA water, but still .

It looks like the West Coast is about to be swarming with hundreds of millions of face-huggers, but these are actually only harmless plastic “shade balls” that the LA Department Of Water And Power deliberately dumped into the city’s reservoir in 2015.

Stimulating it the most epic suit of throwing shade in city history .

There’s about 96 million balls in the reservoir, which means, even though each individual whatchamacallit only expenses 36 cents, the whole project cost around $34.5 million.

It’s the most expensive teabagging imaginable .

And while dumping the entire GDP of a small country straight into a water supply would ordinarily be labeled a bizarre cataclysm, there’s a good reason for this: the balls reduce evaporation and slacken algae growth. The department calculates it saves around 300 million gallons per year, and merely seems a little like alien caviar.

Alien caviar is $120 a plate at Spago .

4

The World’s Biggest Solar Power Plant Looks Like A UFO Launch Pad

Deep in California’s Mojave Desert, there’s something that looks like a Prius charging station for electric UFOs.

Note: This is one photo , not several put together .

That’s the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, the world’s largest solar plant, and a major step toward California’s goal of providing 33 percent of the state’s electricity from renewable sources by 2020.

To milk that much juice out of the shine daystar, you need a hell of a lot of mirrors. Around 173,500, to be precise. Their undertaking is to take most of the sunlight that falls on the 3,500 -acre facility and concentrate it all onto one of the three Ikea-brand Eyes Of Sauron that stand at the center.

Water inside the nearly 460 -foot-tall towers is turned to steam and funneled into a turbine. The facility has a capacity of 377 megawatts, and at full production, the plant could light up 140,000 California homes.

The environmentally-minded developers constructed sure to relocate an endangered species of tortoise so that they could develop on its natural habitat. So it’s various kinds of ironic that the facility unwittingly triggered a bird holocaust. See, those invisible beams of sunlight that the mirrors are shooting out are hot enough to instantaneously incinerate anything that passes through them. Regrettably — well, you know how a bug-zapper works? Imagine one big enough to work on rare falcons. Merely the rarest . Reports suggest that Ivanpah incinerates an unsuspecting bird around every two minutes .

3

The World’s Most Powerful Lasers Look Like … Well, The World’s Most Powerful Lasers

According to the University Of Rochester, the purpose of its Laboratory For Laser Energetics( LLE) department is “to investigate the interaction of intense radioactivity with matter.” This is a research grant-friendly route of saying “blow shit up with lasers.” Lasers like this one TAGEND

Fact: This is how God constructed the universe .

That’s the 30 -foot-tall, virtually 330 -foot-long OMEGA laser system. Among the world’s most powerful lasers, its rays deliver 40,000 joules of ass-shattering energy in a single billionth-of-a-second detonation onto a fuel pellet the size of a pencil tip-off. Here’s what it looks like from inside the chamber, moments before a bumbling lab intern turns you into The Hulk.

It’s “ve called the” OMEGA laser because it’s the last thing you’ll insure . The OMEGA laser is in friendly competitor with the National Ignition Facility( NIF) in Livermore, California. Unlike the OMEGA’s direct-drive method — zapping a gasoline pellet with lasers — the NIF focuses an insane 192 lasers on a tiny golden enclosure, producing X-rays which then strike the pellet. It also appears exactly like a Borg sphere TAGEND

Or their sex toy .

From the inside, it looks like something Jeff Goldblum is about to blow up with a Macbook virus TAGEND It is also able to locate all mutants worldwide .

2

The Soviet Union Actually Had Crazy Giant Tesla Coils

In Command And Conquer: Red Alert , the Soviet team could construct giant Tesla coils that incinerated hapless Allied soldiers. Turns out that wasn’t made up: They truly existed.

Weird. We didn’t realize “Thor” was a Russian name .

These 130 -foot lightning towers, tucked away in secluded woodland 25 miles from Moscow, weren’t designed to obliterate encroaching adversaries, but simply for scientific curiosity and testing electrical insulation. At least, that’s what they tell us.

They tested the electrical insulation of Gulag prisoners .

The High Voltage Marx And Tesla Generators Research Facility is a mess of tubes and wires that could have been inspired by mid-century science fiction B-movies. And when it’s set to full power, it can match the entire country’s electrical potential with lightning ten-strikes that rise 500 feet into the sky.

Targeting the USSR’s number-one enemy: hope .

It is now the property of the Russian Electrical Engineering Institute and supposedly not at all evil, though it’s still operational, and can sometimes be seen sparking its bolts high into the air for what we are sure are utterly benign scientific purposes.

Today, all it does is pump out high-energy Putin memes .

1

Fusion Power Research Looks Like Something From An Alien Sequel

Fusion power is a clean, sustainable energy source that, if mastered, would eliminate our need for non-renewable fuels and offer dirt cheap electricity for everyone on countries around the world. All we have to do is find a way to imitation the conditions at the core of the sun. Easy!

Toward this end, MIT has created the “Alcator C-Mod, ” basically a large metal donut that confines a stream of crazy-millions-of-degrees-hot plasma within a magnetic field. Don’t worry, they tell us the reaction occurs on a small scale and is pretty well contained, so it probably won’t kill you. Unless you bang its giant superconducting girlfriend.

Then, it’ll smack you so hard you’ll get permanent fisheye vision .

Unfortunately, the Alcator C-Mod was necessary to shut down after losing sponsorship from the Department Of Energy, though not before setting a new fusion world record on its last night of operation. In spite of attaining temperatures of 35 million degrees at an unprecedented 2.05 atmospheres of pressure, federal fusion funding was diverted to France’s International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor( ITER ), soon to be the world’s biggest, baddest magnetic imprisonment experiment.

Though its model here is more of an adorable Star Wars droid .

Scheduled for finish in 2015, numerous delays have pushed that to 2021 at least, with its cost soaring from an initial$ 5 billion to about $40 billion and counting. But hey, it’s shaping up to look dope as hell.

It’ll be an amazing venue for the 2022 World Cup .

Meanwhile, in Japan, they have the Large Helical Device( LHD ), a project of the National Institute For Fusion Science in Toki, Gifu Prefecture. The LHD attempts to mimic the action at the core of stars by trapping hellishly hot plasma within a magnetic field restricted inside a twisted 44 -foot metal tube. More importantly, though, it looks like they ripped the design straight out of H. R. Giger’s nightmares.

From the outside, the LHD looks pretty innocuous TAGEND Just a run-of-the-mill planet mill .

But on the inside, its eight intertwining superconducting coils look like the kind of porn that Japanese robots won’t admit to watching …

They had to invent four new dimensions to construct this .

To achieve fusion without the gravitational advantage of a body 330, 000 times the mass of the Earth, terrestrial fusion devices must heat ga to about 100 million degrees Celsius. This roiling hell-stew would speedily melt the very machine that created it, so magnetic fields exerting 1,000 tons of pressure per meter are required to separate the plasma from the inner walls. For some reason, this requires giant metal tentacles.

We’re not about to question it; they seem to know what they’re doing.

Also check out 23 Real-Life Mad Scientists Deleted From Your History Books and The 6 Most Baffling Science Experiments Ever Funded . Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out 10 Ways Science Says You Can Seem More Attractive, and other videos you won’t insure on the site !

Follow us on Facebook, and let’s be best friends eternally .

Read more: www.cracked.com

The post 7 Giant Crazy Real Things That Look Straight Sci Fi, Son appeared first on Top Rated Solar Panels.

from Top Rated Solar Panels http://ift.tt/2h7Cpg5 via IFTTT

0 notes