#what i mean is like. the role of that profession (entertaining) was mainly male

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

reading and learning

#did u kno that at the time of nobunaga#who nago is implied to be the retainer of#geisha were typically male#i bring this up because chipp refers to anji as a geisha out of some incomplete understanding#but did you know nago refers to anji as geisha also in jackos route.#once again. reading way too into it LMAO#i say geisha are male. theres a lot to say about the word itself which really just means arts person#what i mean is like. the role of that profession (entertaining) was mainly male#up until it wasnt lmao#the point is. i will say it's more likely that he does think its a bit/chipp is dumb and hes going along with it#but also what if he was just like. well that seems right and i dont know enough abt them to dispute it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

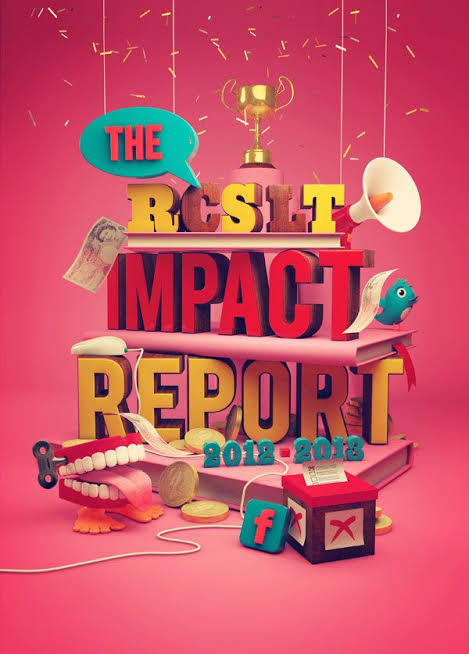

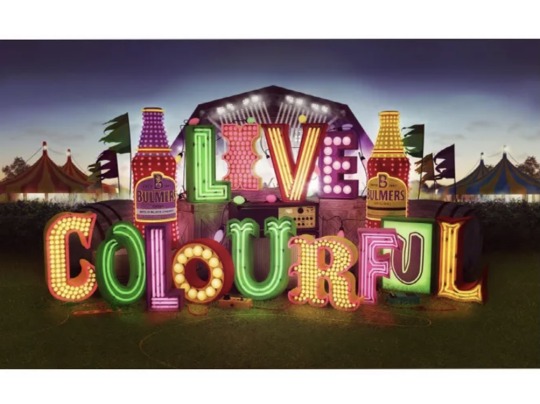

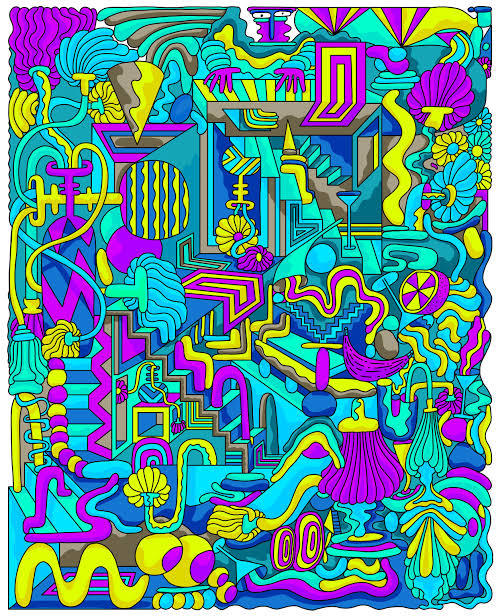

Research: Project Defuture The Future

Randolph Lamonier

Randolpho Lamonier, is a visual artist from Minas Gerais, born in 1988.

He developed several works, specially photography articulated with other languages. He deals with several daily experiences in the city as a form of work, in which photography leads to multiple forms of symbolic exchange.

His work moves between different media, with a leading role in the practice of textile art, drawing, photography, video and installation. In his research, word and image are always together and tend to talk about micro and macro politics, urbanities, sentimental lies, chronicles, diaries and multiple crossings between memory and fiction.

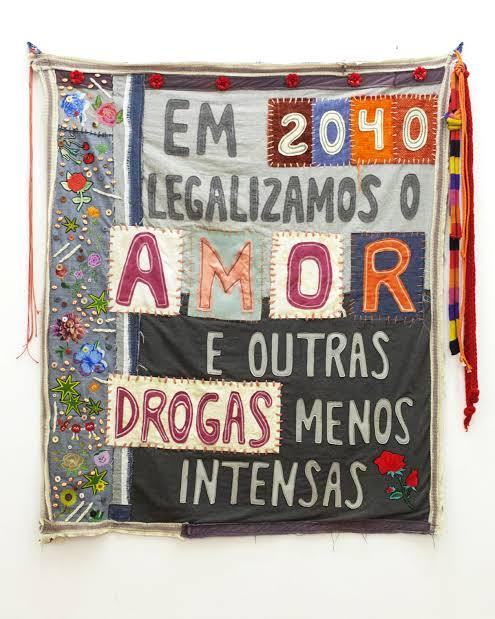

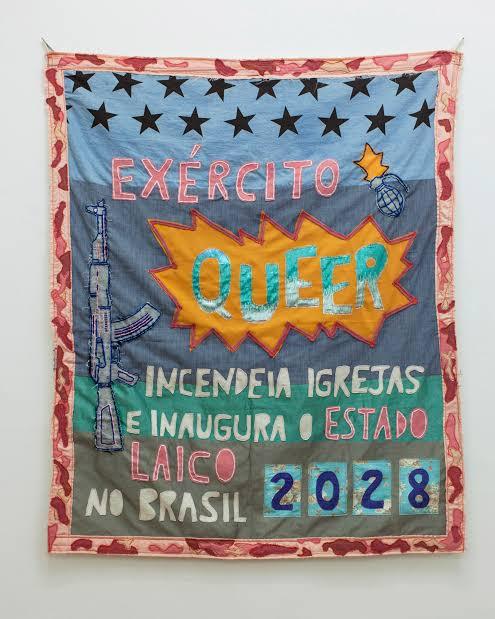

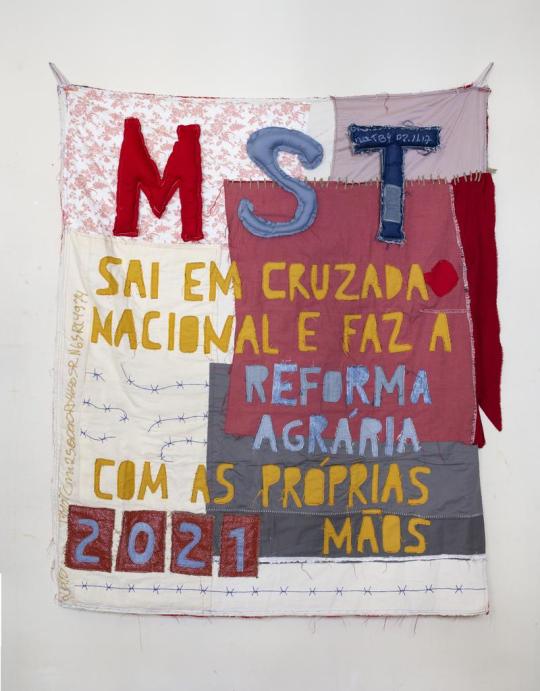

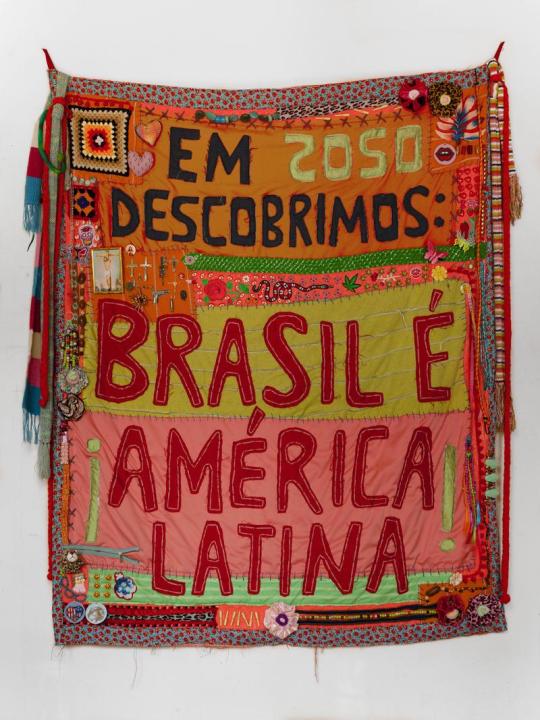

The work done in fabric and embroidery brings sentences like: “ In 2040, we legalized love and other less intense drugs”, and is part of a set of creations in which Lamonier elaborates predictions based on thoughts about the present. “ I always create these works from guidelines that I consider urgent”, explains him.

In the words of the artist himself: “I make flags with what I have. I have never been so foreign. I draw poems, calls for help, war cries, everything is very urgent. The air is contaminated, the floor is covered with debris; sheets, pots, ropes, concrete, broom. Under the rubble the seeds grow in a hurry”.

Perhaps something more interesting than his incredible flags, are the themes he addresses, most of the time making a prediction of the future, about things that could happen in Brazil.

He is indignant with everything rotten that has in Brazil, from the corrupt government, the uncontrollable drug trafficking, the misogynistic society that still exists in Brazil and in several Latin countries, up to the violence itself.

He creates these flags in order to have some kind of hope for Brazil in the future, creating an utopia, where the problems would be thrown away.

David A Smith

Is a British designer who is specialized in lettering.

He started his own company own sign writing company in 1990 and after 13 years sold the business in 2003 to concentrate more on hand crafting lettering and glass gliding. His main techniques include water and oil gliding, acid etching, French embossing, screen printing and sign writing.

His career in sign writing began in 1984, when he left Westlands school in Torquay, age 16 and was apprenticed for 5 years with Gordon Farr & associates. They were a traditional sign writers, who had come up through the ranks and Gordon, had an uncanny ability to paint letters, accurately laid out, without even a sketch. Under their tutelage, David became an accomplished draftsman, and a accurate letter painter.

This gathering of talented sign artists, carvers and muralists experts. David passion for creating elaborate, ornate mirrors&reverse glass signs of distinction.

In 1992 he set up his own business in England dealing every aspect of sign trade from vehicle graphics to 3D installations.

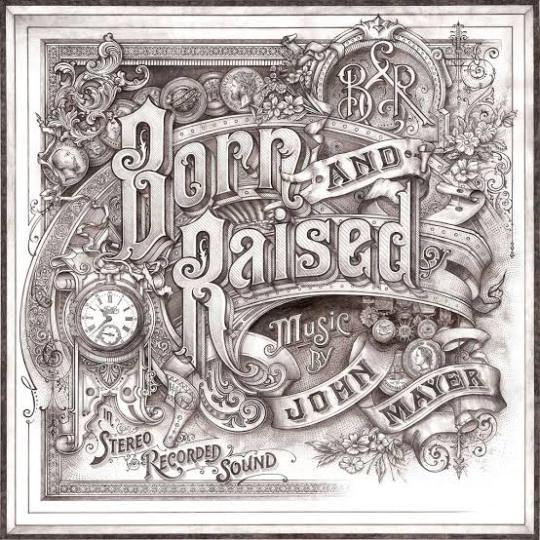

In 2012, Smith was hired by the singer John Mayer to design the album cover, of ‘Born and Raised’. The cover was styled like 1900 trade card.

He has also worked on posters and other merchandise associated with the album and single.

He was also commissioned by Jameson Whiskey to design a st.Patrick’s Jameson Whiskey bottle for the brand.

David sold the business, to concentrate more fully on gilding, painting e acid-etching glass, adding cutting, so that he could fully replicate the Victorian glass work he admire so much.

Thomas Burden

Burden is a senior designer at the design boutique “I Love Dust”.

He likes to produce work that references the pieces of vintage tat and printed material he gets from car boot sales and junk shops. Thomas Burden has created work for book covers, ad campaigns, music videos and magazine editorial to packaging, and even animations.

Thomas Burden was always encouraged to be creative, he was allowed to draw murals on the walls of his house, when he was very young. He had many references to do his drawings, in his grandparents house, full of Alpine memorabilia and indigenous art.

Toys weren’t allowed in Burden’s life as a child, so he was always looking at catalogs full of brightly colored things.

So in his works he tries to transmit that nostalgic journey to his childhood memories.

In each work there is a maximization of colors and textures and his great influences are: the film director Wes Anderson and the artist Mark Ryden.

On his own words: “ I was lucky enough to have a pretty idyllic childhood. I grew up sailing and skiing and traveling, so our house was full of souvenirs that parents collected, along with various bits of old boating junk and pieces of old cars”.

As an 3D illustrator / Art director from UK. He had worked with many different clients such as Nickelodeon, The New Yorker, Apple, McDonalds, Penguin, Bloomingdales and Ford.

His signature style is mainly the toys that he was never allowed as child, combined with fairground / neon signage and anything bright and fun that catches everyone’s eyes. He create works in Cinema 4D, also using the Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop and After effects.

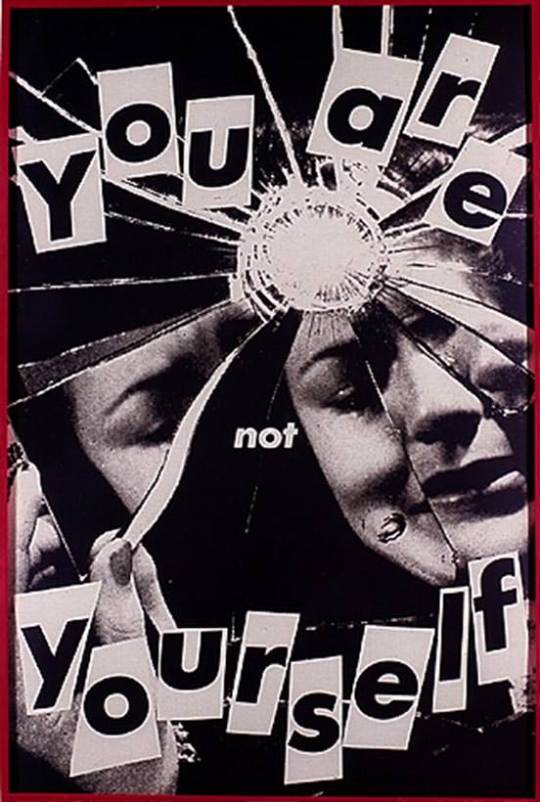

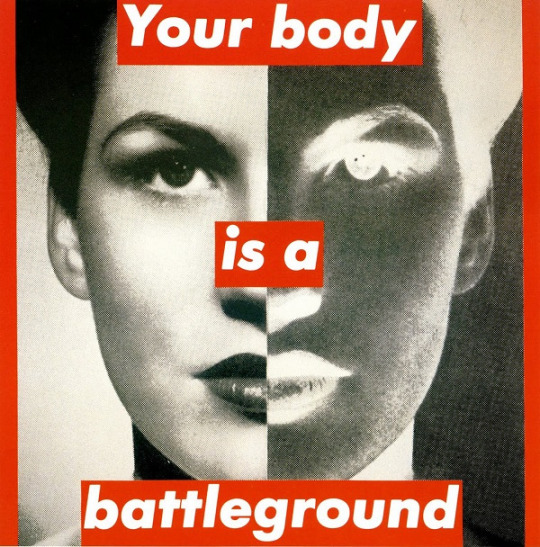

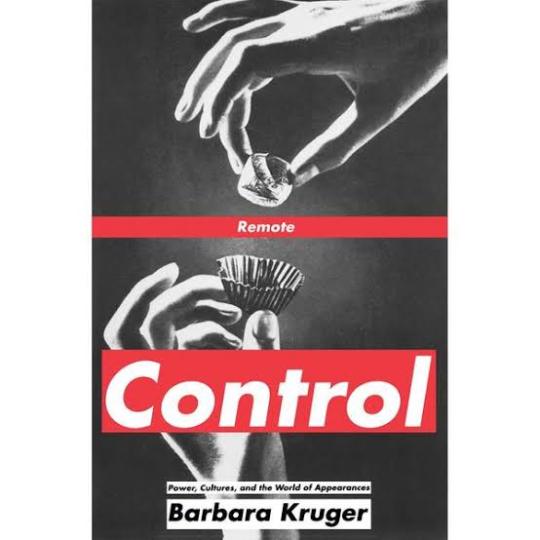

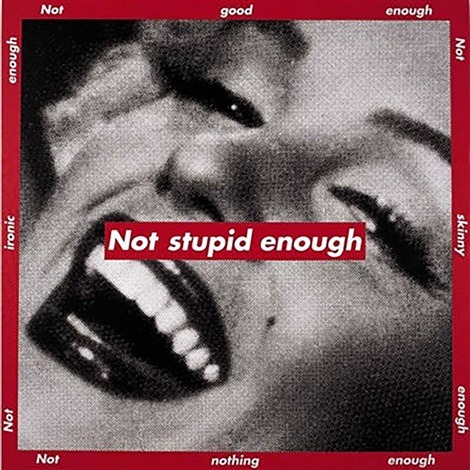

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger is a postmodern artist who was born in 1945 in New Jersey. Having grown up in a middle class family, her first job was as an operator. In 1965 she graduated from The Parson Design School in 1965 and worked as an art director in different magazines. By breaking some barriers of the modern art, Kruger and other women artivists ( art + activism) demonstrated not only against the bonds of patriarchy in society, but also within cultural production. Being an artistic medium an environment built largely by male hegemony, feminist art presents itself as a mean of liberating women. Her works examine stereotypes and the behaviors of consumerism with text layered over mass media images. Rendered with black and white, with a red background, Kruger’s works offer up short phrases such as “Thinking of You” and “I shop therefore I am”. Kruger uses language to broadcast her ideas in a myriad of ways , including through prints, T-shirts, posters, photographs, eletrônico signs and billboards. Despite the work of feminist artists of the twentieth century to change the way women are portrayed in the art world, today this representativeness still confined by a backward ideal. Thus, the work of Barbara Kruger proves to be even more relevant and undoubtedly necessary today.

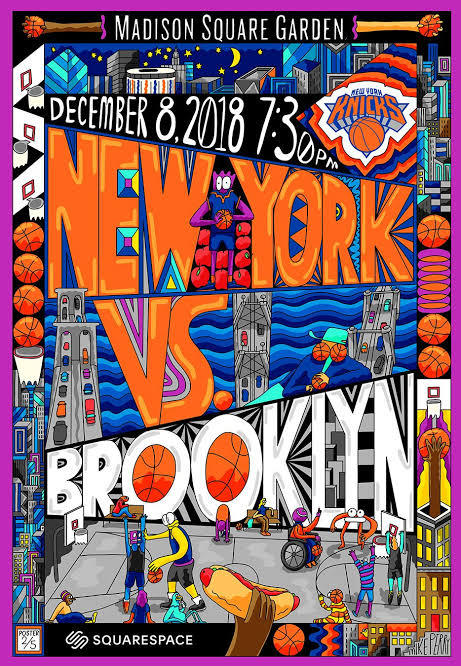

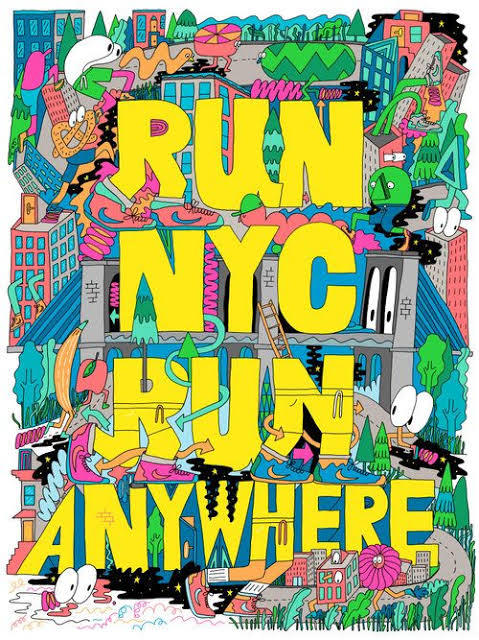

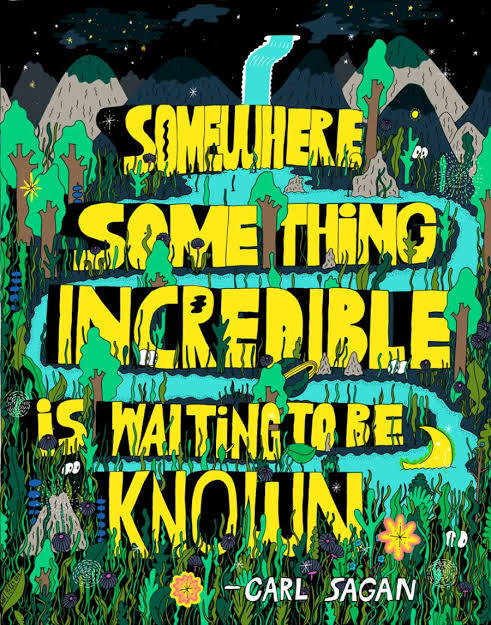

Mike Perry

Mike Perry is an artist that makes paintings, animation, sculptures, books, public art installations, monographs, silkscreens and more. Mike Perry was born in Missouri, United States, and grew up in Kansas City. He started drawing at the age of four. He attended to the College of Art in Minneapolis, and earned a degree in graphic design. Mike Perry's style of using extremely vibrant colors, and making totally stylized designs with a lot of personality is something that draws my attention mainly. His letters are always around a totally imaginative space, which can be both a forest and even a city. The creativity in making those compositions for his posters is something very captivating, not necessarily making a poster that matches with the reality, but doing something perhaps lysergic. His works can be considered love notes to the abstract, unknowable future that is all possible in the present. Illustrator Ana Benaroya said that , “Mike Seems like a modern surrealist to me. His works feels like a childhood memory of slipping down a giant water slide during summer. Slippery and wet and innocent but not innocent. His drawings feel like they just fell right out of his brain onto the paper”. I think he is a great influence, especially for this project. Because I'm wanting to go overboard with the lyrics and the drawings, wanting to do something totally experimental, doing something absurd and creative at the same time. And with this nature theme, I want to make posters with extravagant animals and unconventional scenarios. How he uses photoshop and Procreate for most of his work. I would like to use Photoshop again for this job to continue to learn painting techniques.

Filipe Grimaldi

Filipe Grimaldi is a lyricist and designer. He has been working in the graphic design market since 2006 and, in recent years, has been focusing on the study of manual techniques of calligraphy, lettering and letter painting, migrating part of his work to the development of letterings and commercial decorative painting.

He even give practical classes in ateliers of other institutions. His works can be seen on walls, slates and thousands of plaques that circulate around with his characteristic traits.

Filipe Grimaldi works on the primary chromatic contrast, a key element for the graphic construction of the alphabet.

Letters, words and sentences are organically raised, avoiding the precise math of right angles.

I met Filipe Grimaldi at EBAC in 2019, when he taught a class of typography, teaching how to make a freehand letter. I was impressed, because I saw great perfection and lightness when he drew those letters.

In addition to using several very vibrant colors in his works, even looking like a lettering of an entertainment show.

He even painted on a mural at EBAC, where even I had the opportunity to give a light brushstroke in one of his letters.

For 13 years, Filipe has been specialized in manual techniques of calligraphy, lettering and letter painting. In his own words: “ My authorial research and commercial activities ended up leading me to rescue the calligrapher profession, an almost extinct activity in the development of technology and printing and clipping machines”.

Currently, he teaches typography and calligraphy, for college students, with the goal of encouraging people to try more hand-made letters.

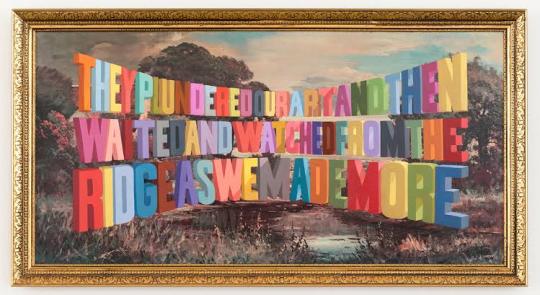

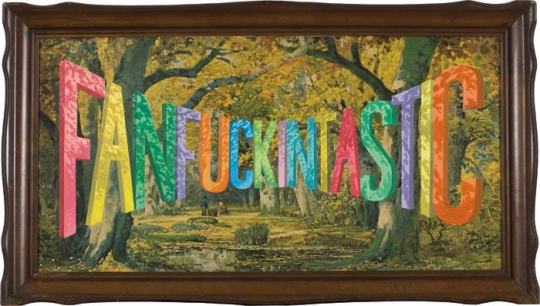

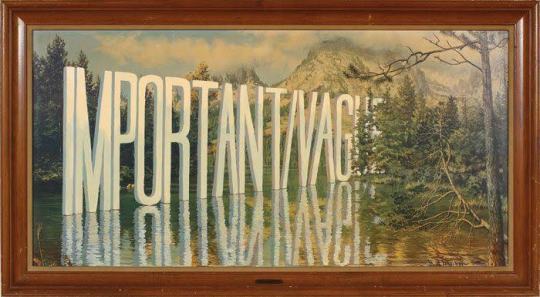

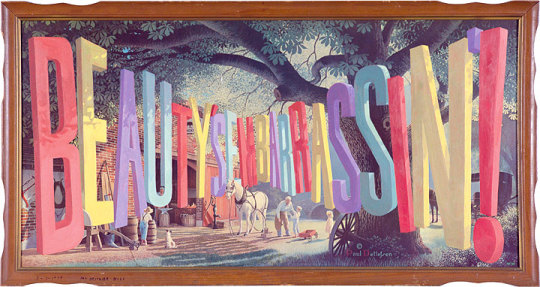

Wayne White

Wayne White is an American artist, typographer, cartoonist and puppeter. A former set and character designer for the television show Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, White produces ironic, often subversive imagery. On Pee Wee’s Playhouse where his work for his set and puppet designs won three Emmys; he also did many voices on the show. He is best known for his word paintings composed of oversized, three dimensional text painted onto cheap landscape paintings he finds at thrift stores and markets. In 2000, he began painting words and phrases, on thrifted lithographs. “When you think about it, you’re surrounded by giant letters and words everywhere”. White said once. “We don’t take for it granted, but the whole American landscape is nothing but a giant letter forms”. One Journalist said his opinion about White’s paintings: “the weirdest landscape painter in America, White uses master painting techniques to create the illusion of words and phrases surreally disappearing into the horizon or jutting out from each lithograph’s place setting.” White’s famous “word art” paintings hang in museums and galleries across America. His paintings features technically proficient and wildly colored phrases that are funny and sarcastic. And critics have praise White’s series for being entryway to the artist mind. Over the past years, White has worked primarily as a fine artist with solo exhibitions of his paintings and sculptures in galleries in New York and Los Angeles. In 2006, he created a giant head sculpture, with a giant lettering next to head. This marks one of White’s other passions, which is sculpting, and he like to exaggerate on the expression, of the characters that he is sculpting.

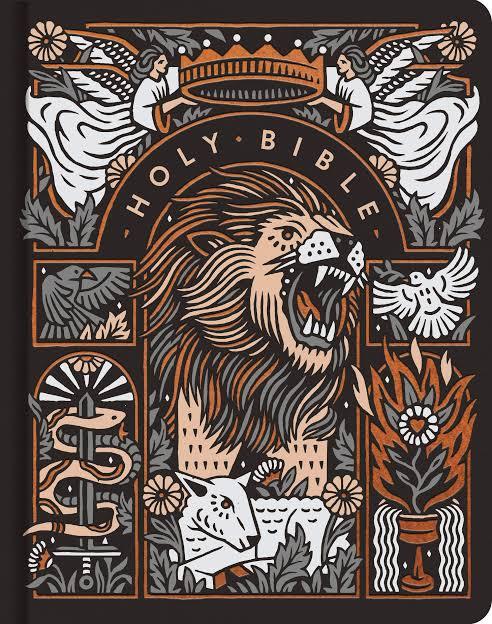

Joshua Noom

Joshua Noom is a famous illustrator who was born in Australia, in 1988. He is very popular in the social networks, specially in Instagram, where his minimalist illustrations and typography have earned him over 60,000 followers. He had created several illustrations for musicians and major brands like, Miller High Life, Sony, and Warner. Today Noom lives at Florida, and he is specialized in detailed and bold illustrations combined with an organic sense of typography. One of his most recent works, was recreating the Bible’s cover, with many other Christian artists. Each artist offers a visual entry point focused on a particular biblical theme or passage, setting a tone of reflection as readers engage with the Bible. I’ve been looking at Joshua works, and I really like the feeling of gritty and inky that he puts in his illustrations. Some of his works feels military inspired and masculine, while other pieces feel soft and feminine, like some vintage postcards that he produces. Something that Josh uses in most of his work, and that connects with my posters, is the use of wild animals and different situations. It can either make a tiger surfing, or even protest posters for the preservation of wildlife. He has a very intense passion for animals, and he enjoys drawing them in very expressive ways. With strong colors, with its minimalist style, and texts with different fonts around it. In a interview Josh even discusses his style “ My inspirations for my style are mostly from music and other art, but one artist that I’ve been diggin’ is Mark Conlan. My style has just kind of developed over the time and I think I will probably keep evolving. After many attempts of trying new things and figuring out what works for me, and what doesn’t for me. I prefer to draw in a more minimalist style, specially using my ink pens. Animals are one of my inspirations, specially here in Florida, we got many different species of birds and reptiles, so like to sit somewhere, and draw any animal that appears, and try to create a composition with different typefaces, to make future posters.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Edthnic Minorities within Media

As a half English, half Thai person it is not often that I see a representation of myself on the big movie screen and nor do I expect to see a mixed actress of my ethnicity to represent me - no, that would be too pedantic. But to see someone that is not Caucasian playing the lead roll would be inspiring.

Media has always projected an exaggerated version of reality and never to truly exist to imitate or represent reality. It is not just ethnic minorities that are being effected by the media’s portrayals – but genders, sexes, sexualities, body types, etc too. TV and Films are predominantly fiction. When looking at films based on History, it is obvious that the film does not represent everything that happened in reality in the span of a couple of hours. And though advertised a ‘reality’ sometimes documentaries or reality TV shows are either fictional or has fictional elements. And so sometimes we must sit back and take what is given with a pinch of salt. Acting is acting and is in a world of fiction. Nevertheless, sometimes when an individual from the majority plays a minority character, it involves some degree of cultural appropriation.

=====================================

When addressing the history of ‘racebending’, it refers to the ongoing Hollywood practice where a director, producer, publisher, studios etc… would changes the race or ethnicity of a character. This act was historically used to discriminate against people of colour. Back then, practicing blackface and yellowface would be used as a way for Hollywood restrict opportunities to actors of colour. And so, the communities of minorities were then helpless and could not control how they would be represented in media and thus led to onscreen stereotype.

In this modern-day society, we have yet to escape the prejudice of type-casting, which is still practiced but in a more subtle manner. The motive of Hollywood however has gradually shifted from the history of oppression and discrimination and more towards the idea of profit and money making with the mentality of ‘If it ain't broke, don't fix it.’

Fig 1. A screenshot from the film ‘The Good Earth’ of Luise Rainer as ‘O-Lan’ and Paul Muni as ‘Wang’

This is not a new topic. In fact, it has been circling around many times throughout the centuries. Dating back to 1937 with ‘The Good Earth’ where Caucasian actors would have pounds of make-up and prosthetics on to play a Chinese family.

Nevertheless, as time passed, the growth of the minority’s population and communities grew excessively large that there are areas like ‘China Town’ popping up all over the western world and there are now more active people of colour acting than there were ever before... Yet after 75 years you would think that mainstream media has barely changed a bit, what with the needless yellowfacing character in the 2012 movie, ‘Cloud Atlas’ with Jim Sturgess in prosthetics instead of casting an East Asian male for the role.

Fig 2. A screenshot from the 2012 film ‘Cloud Atlas’

On the right side, we have the modern-day struggle of lack of representation, however on the left side we also have backlash when Caucasian characters get a racebending transformation. The act of racebending a character for the better happens very rarely, but when it does it is often misunderstood as ‘political correctness’. And even though these actions are merely attempts to level the imbalance in media, if the portrayals are not executed well then it can worsen an already bad situation by creating more stereotypes. Whereas a successful attempt can make a world of difference.

=====================================

The Data

(The data’s will mainly be sourced from the USA (as this is where the main source of influential media derives from) and the UK (as this is where I am situated).

Fig 3. Ethnic groups, England and Wales, 2011

Fig 4. 2010 U.S Census, 2010

As shown by the charts on Fig 3 and 4, it is clear that Caucasians are the dominant ethnic group in the UK and the USA.

Fig 5. University of Southern California studies of 700 top-grossing films from 2007 to 2014, excluding 2011

Fig 5 shows the percent of characters by race/ethnicity in top-grossing films between 2007-2014. Funnily enough, the chart reflects the data of Fig 3 and 4 in light of the real-world percentages. And so, in truth the feelings of minorities being underrepresented is not just a whim, but a fact. So now the question is, if the real-world percentage and the media industry percentage correlates to one another, then why is there an issue if the media is reflecting what the real-world truly is…?

Well this circulates back to the practice of stereotyping, and though sometimes it can be highly entertaining, it can also come across as an insensitive mockery of a culture.

“It’s kind of like a catch 22, in order to get into the industry and working you kind of have to just do those role just to get some kind of credit.” - Ally Maki (Actress)

Like all profession, actors and actresses of colour or not will have to start from the bottom. However, to even stick your foot into the door of entertainment means to become dancing monkey of sort and allowing to be scripted to as a stereotype, which can be demeaning on the person and the people they are representing.

Fig 6. My Ethnic Minorities within Media public survey (Feel free to participate in my survey - Click Here)

Through my own online survey, I gathered the public’s opinion on ‘Ethnic Minorities within Media’. I asked questions like ‘whether they think there is an issue in media’, ‘the difference between then and now’, ‘how it affected them’, their views of it all as a consumer’ and so on. The survey was accessed worldwide and had 80 responses from people of all ages and backgrounds.

Unsurprisingly my online survey also reflects the real-world percentages. However, the responses had high results of concern and acknowledgement on the subject matter as well has some interesting reasoning of why the topic is not concerning.

52 out of 80 agreed that there is an issue with ethnic minorities within media. 20 out of 80 somewhat feel there is an issue with ethnic minorities within media. 8 out of 80 disagree that there is an issue with ethnic minorities within media.

Having asked those taking the survey to elaborate on their chosen answers, people of all ethnicity shared one key point in their response, which addressed the idea of ‘representation’ and how there is a lack of it and they also picked up on the negative theme of stereotyping.

Interestingly, some felt that since the percentage of media and real-world ethnic popular are the same, that there is not an issue with ethnic minorities within media and said;

“In the end, it's all about individuality if you want to prove yourself to the society. Being a minority simply means you don't get a head start in life.”

“Hard workers will get to where they want to.”

Note: These two comments were made by Southeast Asians.

youtube

In a sense, it is all a matter of opinions and perspective when you are look at it as an outsider. Anna Akana – an Asian American filmmaker, producer, actress and comedian, spoke out about her experience in almost landing a lead role in mid-2016. However, she was later disappointingly offered to be re-casted as a supporting role due to the uncontrollable colour of her skin. Which was confusing since she had been working hard since the beginning and overall hustling her way through the entertainment industry. But without a doubt there is no denying the underlining history of oppression and discrimination that is still it existing today.

=====================================

The Importance of representation

What is representation? It is the description or portrayal of someone or something in a particular way. And why is it that representation is so important? Well… it is important to be represented because without representation there would be missing and untold stories. And without a depiction of oneself, people will feel unheard, unseen, ignored, and ultimately oppressed. In a growing world as diverse and complex as ours, the last thing we want is do is revert back into the dark days and lose a large portion of peoples sense of self. The impact of representation begins at a very young age where our sense of identity is only just forming - and not having that visual connection can make one feel like an outsider and effects can ripple out through the rest of our lives. Being represented illustrates the possibility of achieving anything, whether it be growing up believing that you can be an entertainer or an Olympic athlete. Seeing people a-like, accomplishing their dreams, breaking barriers, and destroying stereotypes shows us our own potential. Reminding us that we are not alone in our experiences.

Casting established Caucasian actors as characters of colour will definitely bring in profit to the producing company however, it will have a huge and harmful impact on the underrepresented communities of colour and the battle for recognition. On the other hand, casting Caucasian characters with actors of colour will have little impact on Caucasian children and consumers as they have plenty of already existing representation of themselves to relate to.

In recent years, shows like Asian American family sitcom ‘Fresh Off The Boat’ and ’Dr. Ken’ came to exist and were airing at the same time in 2015. And ‘Blackish’ which came a year before and portrays the daily life of a black family. These TV shows has a highly positive factor and that is showcasing a perspective of daily life - one from a more diverse outlook. These shows are not your usual standard middle class pale families we are used to seeing, they are their own and were not just hired to hit diversity quotas. These rare portrayals of people of colour challenging historical stereotypes is truly empowering and will boost the esteem of self-identity. These shows matter. These shows should be the norm.

Fig 7. D.Va and Voice actress Charlet Chung Overwatch

In addition, we have media such as video games and comic novels where the companies rely on the continuous support from the fans. These companies cater to the audience’s more than the film industry as the fan base loyalty is needed for them to continue on making money. A small but gratifying example would be the choices of voice actors for Blizzards 2016 video game ‘Overwatch’ - a competitive first person shooter game that is based on a futuristic version of our world. The playable characters are from all over the world, with all kinds of ethnicity and sexuality. And although they are animated and appear to represented all sorts of cultures, Blizzard went beyond that and hired voice actors according to the ethnic background of the video game characters. Another fantastic fan driven company is Marvel. Who has within the past couple of years been racebending their original characters to be more inclusive in the comic book world, this is a liberating action as now child of ethnic minorities can feel inclusive and relate to the hero.

=====================================

Who’s to blame?

It is very easy to point fingers at Hollywood and blame them for the lack of representation of the minority community of all genre. But then again, Hollywood alone is not the problem. It is us, the consumers as well who are unconsciously funding them by purchasing tickets for the show. In some ways, Hollywood does a good job at recreating some very real and aspects of history. Nevertheless, the racialisation is ever so complicated and while it is fiction it is so very real.

Changing the system

Ultimately, we as consumers of the media, must stand up against the prejudice representation of the minorities on the big and small screen by boycotting outlets that demeans the minorities or watch the film at a later date as the opening weekend is Hollywood’s means of income. And on the contrary, support the medias that are heading into the right direction, such as Disney’s 2015 ‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’. Disney ignored the opposing criticism on casting a black actor, John Boyega, as a Stormtrooper and yet the film went on to become biggest domestic blockbuster release of all time. Supporting programs and films like these will certainly guide content creators to seeing that decision like casting a minority is acceptable and will perhaps continue casting more non-Caucasians in the future films. It is definitely a slow progress but it is unquestionably changing and making a difference.

youtube

Youtuber, Philp Wang of Wong Fu Productions makes some valid arguments in his video ‘Don't just TALK about Whitewashing’. He also talks about how Hollywood is not going to change quickly enough for whitewashing to go away. And so, the answer to this is for us (the minorities) to step up and create our own contents.

“Be the change that you want to see in the world” - Gandhi

Sources: Ghost in the Shell announcement [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

#Ethnicity#Minorities#Report#Essay#Conversation#Media#Hollywood#Racebending#Identity#Overwatch#Marvel#Cloud Atlas#Fresh Off The Boat#Dr. Ken#Blaskish#The Good Earth#Repersentation#Anna Akana#Wong Fu#Philp Wang

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOMELAND: TO PLAY OR NOT TO PLAY by Robert Boyers

from Salmagundi, Summer 2017 [The TV Issue]

In the 1960s, when I was just out of graduate school and active in the anti-Vietnam war movement, I counselled other war resisters and knew what I knew. One thing I was sure I knew was that the CIA was an organization ostensibly committed to safeguarding our liberties while routinely betraying pretty much everything that the credulous among us associated with the standard American virtues. Of course my convictions about the CIA came from the books I’d read, the films I’d seen and my own lively imagination. Though I had no direct access to any employee of the CIA, and rarely if ever spoke with anyone who would have thought to defend it, even the more public actions and pronouncements of CIA officials persuaded me that mine was no blind prejudice but informed opinion. When I began teaching at the college level in the late 1960s and a few of my students asked me to recommend them for employment at the agency, I told them there was no way I could send anyone I cared about to work there. Soul-destroying, I said, certain that my own virtue was at stake in this refusal, and not in the least bothered by the fact that this gesture on behalf of my own precious virtue cost me nothing.

Though the years have not been kind to a great many of my former prejudices and avowals, my sentiments on the subject of the CIA have not altered very much. Not even a modest acquaintance with two CIA employees, distant relatives in my own extended family, has dislodged my sense that the people recruited to those ranks are less than wonderful examples of humanity. Though I have agreed to recommend a few recent students to the agency, I’ve subjected them to strenuous interrogation, to ascertain at least that they know what they’re getting themselves into. One of them, an especially bright and self-possessed young woman, told me she thought I was naïve about the agency and, so far as she could tell from our conversation, “probably naïve about politics in general.”

“You mean, naïve as in ‘liberal?’” I asked.

“No, I mean naïve as in not very well informed,” she replied.

That same young woman has now been with the agency for more than a decade, and almost two years ago showed up at an alumni weekend “mini-class” I’d agreed to teach for returning Skidmore College alums. She sat in the front row and raised her hand at the first opportunity she had, beaming with confidence and bristling still with a sort of controlled hostility that was yet somehow confiding and weirdly affectionate. “So,” she asked, “you don’t hear in anything you yourself say any traces of the political correctness you think is such a problem on American campuses?”

Later she followed me back to my office and asked if I had time to just hang out with her for a while. “I’d ask you to lunch if I was sure you wouldn’t think I was flirting or something,” she tried, playfully teasing her 72-year old former teacher. Soon she informed me that her work at the agency was everything she imagined, and more, but that she’d always been grateful for my “cautionary fantasies.” Why grateful, I asked her. “Because you cared enough to worry about me,” she said, “and if you weren’t such an old guy, I’d have made it my business to win you over to me and my way of thinking.”

We went on in that way for at least an hour, and eventually—I couldn’t help myself—I asked her if she’d seen the television series called Homeland. She had. And what did she make of it? She liked it, more or less, and didn’t at all mind seeing herself in one or two of the principal characters. Not Carrie Mathison, I allowed myself to suggest. No, not her, my companion smiled. “I don’t tend to identity with persons who are mentally ill, or obsessive, or self-destructive.” And you don’t think the agency often attracts people who are sort of fucked up, I asked. “Nice try,” she said, “but no, not really, and if you think about it—more than you have, apparently—you’ll agree that there are plenty of agency characters on the show who are no more fucked up than your average English department colleagues.”

Of course it occurred to me that, in flatly dismissing any possible connection to Carrie, my former student—from here on, let’s call her Jane—had denied any attraction at all to the most powerful woman in Homeland. But then, Jane did not appear to be terribly interested in women’s issues, and took for granted that strong women like herself were free to create the lives they wanted. Did it seem unusual to her, I asked, that Homeland should be dominated by a female agent?

“Not really,” she said. “And why would you think that?”

“Only because lots of people have made a big deal of it.”

“It’s exactly the wrong way to think about Homeland,” Jane said, “to think that it’s a show about women or men or the war of the sexes, when so obviously it isn’t. That’s the trouble with the gender thing, and believe me, I had it up to here with that when I was a student, all of that pretending that everything has to come down to that.”

All of which seemed to me plausible, direct, attractive. Jane was impressively firm in repudiating what seemed to her untenable, intellectually dishonest. There were other kinds of agents, we agreed, who might conceivably, once upon a time, have inspired legitimate discussion of “the gender thing.” The Eve Marie Saint character, Eve Kendall, in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, or the Ingrid Bergman character in Notorious. Women who attach themselves to men, sleep with them—in Notorious the Bergman character goes so far as to marry the Claude Rains Nazi character—so as to serve the purposes of the agency that employs them. But these earlier figures were, in their very different ways, femme fatales, and Carrie never quite plays that role, and for all of her breakdowns and vulnerabilities, never quite does what she does simply because she is a woman who can be manipulated by powerful superiors to do their bidding.

“Do you think you were more protective of me, more worried about my joining the agency,” Jane asked at one point, “because I’m a woman and you think that women need more protection than men? I mean,” she continued, “if you think of me maybe doing the kinds of things that Eve Kendall did, well, that kind of association would be pretty powerful for a guy of your generation.”

Though I professed not to believe that Jane, as a woman, deserved or needed more protection than a male student would deserve, I couldn’t say with certainty that she wasn’t on to something there. In any case, I was willing to entertain the thought, and to come back to it later on. And I was sure that Jane had done well for herself, made the right decision to join the agency, which had not in any way diluted her sense of self or made her cautious. Never diplomatic, she remained, so far as I could tell, a truth-teller, and if she had learned to swallow any kind of ideological line, that was nowhere discernible in anything she had come to say to me. Because I was reluctant to think of her engaged in the brutal and disgusting work depicted in Homeland, I allowed myself—foolishly, no doubt—to imagine that she was a different kind of operative. Not a desk worker but a nice operative, who’d had the very good fortune to study with me and wanted still to believe that I had helped to shape her. As I say, foolish to think this way. No doubt. And yet I did see, unmistakably, that though this was no saint, she was also very definitely not a monster.

Of course Homeland features a wide range of monsters, from petty bureaucrats to fanatically zealous field-workers and coldly efficient contract killers—and these are only the monsters who work for the agency. On the other side are other kinds of monsters, Islamists mainly, who think that their plots and executions and terrorism will soon create the world-wide caliphate their leaders have been dreaming about. Occasionally it is not possible to differentiate between the calculating awfulness of our monsters and theirs. The coldly efficient agency types who trade in betrayal seem often to deserve the enmity of the others. Any illusions about what may well be required of an agency operative will be rapidly dispelled by a season of Homeland. When a season five boyfriend of Carrie Mathison discovers what she has done with her life over the course of her agency career, he rightly asks how she can live with herself. Of course Carrie also exhibits a standard repertoire of virtues. She is sometimes loyal and even loving. She has a daughter she professes to care about. Often her lip trembles with genuine emotion and her eyes fill with tears of pity or remorse. Seizures of self-loathing occasionally overwhelm her. And yet she remains throughout a terrifyingly unstable and often loathsome figure. If she is in some respects the face of the agency, then the agency is a fearful thing, reliant as it is upon persons who are willing to do all sorts of things that are not to be done.

In some respects the counterpoint to Carrie in Homeland is her mentor, Saul Berenson, who is portrayed, intermittently at least, as a sane and attractive agency official, a realist, vulnerable to misgiving and despair, someone with whom it would be possible to have a conversation and a disagreement. Who might tell you, without condescension, that there are more things on heaven or earth than you had ever dreamed of. A man with real power but with no appetite for the trophies or emoluments that come with status or position.

But then Saul is more, and less, than the several virtues he exhibits. In fatal ways he is defined by the agency he serves. Rarely anything but lucid, focused, committed, he can also be counted upon to do his duty and to accept that this will sometimes entail violence, treachery and mayhem. Seated next to him, as I imagine myself at the Passover seder he attends at the home of the Israeli ambassador, I think of him as simultaneously companionable, direct and slippery. An ideal mentor, perhaps, for my former student Jane, who will think him much more of a realist—and thus more reliably knowledgeable—than her old English professor back in small town America. I turn to him and note, at the Passover seder, that he doesn’t seem to mind the sweet wine, then ask him a question and expect the practiced response of a man who knows the difference between truth and lie but has mastered, overcome his predilection for the one above the other. Though he is by no means a man of a thousand faces, he is, all the same, someone who can be trusted only to move efficiently within the constraints to which he has sworn his allegiance. If he is capable of swerves and the unexpected, he yet remains “true” only in his fashion, and that is the fashion of an agency stalwart who knows better than to demand of himself anything not compatible with the long term interests of the organization.

When I try to place Jane on Saul’s team, try to see her with him, following his directives, I fear that she too may be something of a lost soul—however much I mistrust the extremity and imprecision of such a term, to say nothing of the presumption entailed in applying it to someone whose interior life has not been revealed to me. And in truth I’ve never quite been secure in my impression that Saul himself is other than an honorable man. Certainly he looks good whenever we compare him—as we often do—to others who work for the agency. Though it is not possible to forget that, for all of his probity and steadfastness, this paragon of agency virtue can set up a protocol in which a trusted operative—an important character named Peter Quinn—will show up periodically at a Berlin post office box, pick up a slip of paper on which a name is inscribed, and then go off to assassinate the person, about whom he knows absolutely nothing, and with no questions asked. Sure, I can hear someone whispering in my ear, as I formulate my standard moralistic objections, really, truth be told, you want Saul to establish that protocol if it is designed to eliminate known terrorists and their enablers. And Jane herself has once or twice reminded me, in passing, that an assassin like Peter Quinn is not only a necessary component in a superpower defense establishment but someone for whom it is impossible not to care as we observe him going about his work in Homeland. “You accept him,” Jane once wrote to me, “the way you’d accept me if I were in his place. Not saying I am, of course, so don’t jump to that conclusion. Please.”

Until those recent sentences came up on my laptop screen I’d wondered if Jane would find the assassin protocol believable. Wondered if my misgivings on that score were not again a reflection of the willful innocence Jane has noted in guys like me. And yet in the end, I can’t help feeling that a mere television series has confirmed for me that such things are “real,” and that in working for the CIA my young friend has inevitably put herself in a kind of mortal danger she is, even now, not fully equipped to acknowledge. And if that impression, or fear, reflects my own continuing innocence, while she moves with a fuller and more mature understanding of the way things are “out there in the real world,” well, I’m willing to accept that there are all too many things I too cannot quite bring myself to fully acknowledge.

One virtue of a show like Homeland is that it complicates everything it touches, though often critics complain that it isn’t complicated enough, or that the complications are unfortunate, given our desire for certain kinds of moral clarity that are hard to come by in such a series. For years now, ever since Homeland began its initial run, critics have complained that its depiction of the Islamic world is anything but adequately complicated, that it offers a one-dimensional caricature of a world defined by Jihad and terror. Though the complaint has never seemed to me at all persuasive, I can certainly imagine a kinder, gentler emphasis than the one adopted for the perfectly legitimate dramatic purposes of the series. The Islamic characters at the center of the action do tend mainly to be involved in subversion and to be poised to commit (or at the least condone) violent acts. More often than not they are unimpressed by distinctions between civilian and military targets, and often revenge and sheer indiscriminate hatred of infidels figure in their plans. Now and then, to be sure, even such characters are permitted to emerge as all too human in their vulnerabilities—to family feeling, to parental love, to old loyalties—and very occasionally a particular figure will seem miraculously insusceptible to the lure of retribution or conspiracy.

But the informing assumption, or bias, throughout Homeland is that Islamists exist in substantial numbers—in the Middle East, obviously, but also in Berlin and other European cities—and that the most disturbing thing about such persons is the unmistakable connection between their faith and their willingness to commit unspeakable crimes. That CIA operatives should want to prevent them from accomplishing their ends is neither surprising nor disappointing. Neither is it surprising that the operatives, however fierce and determined, are by no means depicted as bloodthirsty or fanatical. Neither Carrie nor Saul, neither Peter Quinn nor any other high ranking agency official, is consumed by a desire to exterminate the brutes or to cleanse the earth of all Islamic foes. No one in the series is permitted to make the case that Islam inevitably promotes terrorism or obliges all followers to wage jihad on westerners. In effect, a more balanced view of Islam cannot be expected from a series like Homeland, for reasons that go well beyond the ideological fixations of the agency characters or, such as they are, of the script writers. If radical Islam is depicted as the enemy, that is because there really is such an enemy, and because the CIA operatives at the center of the series must be mobilized to confront it. But any complaint that Islam itself is relentlessly depicted as the enemy, or that viewers of the series are somehow admonished to regard all Muslims as incurably violent fundamentalists, is clearly misguided.

Jane thought it “funny” that I should be looking for greater “balance” in a show that, like it or not, was unapologetically invested in the view that there is in fact a “clash of civilizations” : Clearly, we agreed, the willful insistence that no clash exists is all but completely irrelevant to the design of Homeland. Of course, she conceded, you can see signs of a will to avoid casting things in black and white. But weren’t these moves slight, incidental? I had noted, in one email letter I sent her, a sequence in season five, where Peter Quinn, recently wounded in an encounter, is about to kill himself and is saved by an Islamic man who appears, somewhat improbably, at exactly the opportune moment. When Quinn’s savior brings him to his apartment, we learn that he is a doctor, that he is willing to transfuse Quinn with his own blood, and that the good doctor has ties to a whole cadre of Islamic men who are transfixed by a newly arrived Jihadist militant. Like those other men, the doctor is a man of faith, and like one other fellow who cannot bring himself to follow through on the poison gas attack his comrades are plotting for the Berlin subways, he is depicted as an outlier, a special case. This may pass for “balance” in Homeland, but if it proves anything, as regards the “vision” informing the entire series—again, here Jane and I agreed entirely—it is that wishful thinking about what is out there will be hard to sustain in the face of what is depicted in Homeland.

But then “balance” and “wishful thinking” are never far from my exchanges with Jane when we turn to the series. In an April 2017 email she seems to bristle a bit at my suggestion that the latest season somewhat confirms my worst fears about the agency, fueled by the attention paid to Dar Adal, an agency figure as sinister as any Islamic operative. “He’s one guy,” Jane writes. “He’s not THE AGENCY, for god’s sake. For every disgusting thing he does there’s his opposite number Saul doing what he can to thwart him. But then you want to believe that in every evil move he makes Dar represents the agency, don’t you? Then you won’t have to feel so bad about the depiction of all those nasty Jihadists on the other side. I get it.”

Every now and then, especially over the last couple of years, I wonder at the modest intensity of my exchanges with Jane. Here we are, I think, arguing about Homeland and Islam, about innocence and realism, when really I know nothing about her. What does she do for pleasure? Is she married? Would she mention children to me if she had any? Would she describe herself as a political conservative? Not sure why I haven’t so much as tried to learn more about her. Am I afraid to know any more than she’s offered? Has she in fact signaled that she wouldn’t welcome efforts to invade her privacy? In one email I sent, perhaps a half year ago, in the context of our two exchanges on the subject of “balance” and “wishful thinking,” I quoted to her Roland Barthes’s observation that “what is stupid is to be surprised,” and she wrote back to say that in fact she herself had been surprised by several “revelations” in Homeland, and surprised too by my strange “obsession” with this particular series. Was I “embarrassed” to find myself surprised by things, she wondered, and was this a “status thing,” this “pretense” that really smart people shouldn’t be surprised because they already know everything?

Here she couldn’t help recalling that in one of the classes she’d taken with me as an undergraduate student a dozen years earlier we’d spent two weeks on Henry James’s novel The Princess Casamassima, and that she’d been surprised by my emphasis on the self-deception and “cluelessness” of the idealistic revolutionaries in the novel. I mean, she wrote, “I was surprised that someone like you would be so hard on them.” After all, she added, “even I almost fell in love with them, and I was sure you were at least a little bit in love with them too.”

The first time, I thought, the only time, that Jane had allowed herself to speak—to me—of being in love with anyone or anything. In a way, of course, this was what I had found so attractive about her, her resistance to sentimentalities of any kind. When it occurred to me to ask her about Homeland I suppose I wanted her to resist my own tendencies to regard things in my own habitually right-minded ways. No doubt there was some delusion in believing that a person who worked for the CIA would inevitably be disinclined to see things as I did. But then I had known Jane, a little, and had seen her respond to particular books and ideas in a way that provided some basis for my speculation. Though she continued to repel the questions I very occasionally put to her about her life—no, she couldn’t say whether or not she had been assigned to “dangerous places,” yes, she had been “away” much of the time, and yes, it was always “funny” when I asked her about her “postings”—she assured me that people who worked for the agency were usually “normal people” with “the usual hang-ups and doubts.” But then, she added, “you don’t need me to tell you that.”

I’d been thinking for a while, off and on, about “using” Jane as a figure in something I hoped to write about Homeland, and her most recent emails convinced me that I should. Our exchanges had become more frequent since her alumni week return to the Skidmore College campus, and though we had seen one another exactly once in the dozen years since her graduation, we did have a sort of peculiar “relationship.” And so it was that, with more than a little misgiving, I emailed her in mid-December 2016, and told her that I was in fact planning to use her as a “character” in a piece on Homeland. A character, I wrote, “who says things in what are ostensibly her own words, who has a fictional name, but is said to have worked for the agency and to have been my student.” Someone who has watched Homeland and might now “help me to clarify my own thoughts not only about the show, but also about admirable people who may do terrible things for what they take to be legitimate purposes.”

In less than an hour, Jane replied in an email of her own, assuring me that she’d always wanted to be a “character,” and that she was “thrilled” that I would be the one “to make use” of her. Of course, she trusted that I would not make her into “any sort of object lesson”—a term she said she had first heard in one of my classes. Though she was sure I would never send a draft of the piece to her for “approval,” she really didn’t want to see it until it was published. “Just make sure,” she cautioned, “that you allow me to sound as smart as I am, even if you have to make stuff up.” In this regard, she remembered how I had once written to her about how often characters in Homeland master the art of “playing” one another, with little need or instinct to apologize. As always, she said, she detected in what I’d written “a sort of moralistic undercurrent, as if you disapproved.” And yet, she went on, “who doesn’t play other people? Is it unfair to say that you’ve been sort of playing me, using me to fill up a narrative you wouldn’t know how to construct without me? Not that I don’t like playing along, or being played. Lots of pleasure there—and you don’t want to forget that, do you?, when you’re thinking about those characters in Homeland.”

As always, a letter from my friend—for the first time, in her most recent end of the year email letter, she signs herself, “affectionately, your friend”—inspires me to think of the next one I’ll receive from her, and the one I must now compose to be worthy of her correspondence. We are, after all, in our odd way, conducting a long-term, long-distance conversation—by no means as intimate as the conversation I conduct, two or three times each week, with a few other former students who have become indispensable—, but precious, all the same. After all, my favorite agency operative is never tedious, never merely ingratiating, and she leaves me often wondering what exactly I need to know and why I should think her peculiarly equipped to provide it.

0 notes