#what do you mean people place the tip of the tongue on their alveolar ridge when pronouncing [ɹ]???

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

you start learning phonetics and articulation and suddenly realise that APPARENTLY you have been pronouncing consonants incorrectly your entire life

#what do you mean people place the tip of the tongue on their alveolar ridge when pronouncing [ɹ]???#since when??#i don't do that#linguistics#phonetics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

<j q x> and <zh ch sh>: an in-depth pronunciation guide

Help! I can’t pronounce <j q x>! AM I FOREVER CURSED??

No! You shall rise from the void of bad pronunciation! The gleaming ladder of linguistics beckons and shall guide you to success!

Alright, let’s go!

This, below, is your mouth! (simplified, in paint, please use your imagination) The pointy bits are your teeth - the dangly bit at the back is your velum. The bits that are relevant for us today are the alveolar ridge, post-alveolar space and the palate.

<j q x> are all technically 'alveolo-palatal' sounds. Your alveolar ridge in your mouth is the bit behind your teeth that is very hard, before it goes upwards and gets softer. Your palate is divided into your hard palate and soft palate - the hard palate is the bit that burns when you eat pizza!

Alveolar sounds in English are /t d s z n l/ etc - feel how your tongue is tapping off that hard ridge in the first two. We just have one palatal sound in English, made when your tongue approaches the hard palate - <y>, which is usually written /j/ in linguistics. (<this> means spelling, and /this/ means phonemic pronunciation).

Post-alveolar sounds are sounds which are made when you retract your tongue a bit from the hard alveolar ridge. We have quite a few - /ʃ/ as in 'shot' <sh>, /ʒ/ as in 'vision' <s>, /tʃ/ as in 'church', and /dʒ/ as in <j>, 'jam'. Congratulations, because these all exist in Chinese! If you're a proficient English speaker or your language has them, pinyin <zh> , <ch> and <sh> should be straightforward (though <sh> especially is a little bit more retroflex, i.e. your tongue curled back, than the English). T

Alveolo-palatal sounds are made with your lips spread wide, with the back of your tongue raised to your palate (like in <yes> as in ‘yes’) and the tip of your tongue resting along the back of the teeth.

Compare the two pictures. The first is the pronunciation of the post-alveolar sounds, so pinyin <zh ch sh>, and the second is the pronunciation of <j q x>. Notice how in the second picture the body of the tongue is much higher, and the tip of the tongue isn’t curled back, but resting behind the teeth.

In the picture for the English sounds above, please note that this isn’t totally accurate - Chinese <zh ch sh> as well as <r> are more retroflex - they are pronounced with the tongue curled further back in the mouth - but while your accent may sound ‘off’ if you pronounce them in the English way, it’s close enough that it’s unlikely to be mistaken for anything else, so we’ll leave it there for now. The picture below shows the difference.

In pinyin, <j> <q> and <x> are written with separate letters to <zh> <ch> <sh>. This is really helpful for us, because they are different sounds, but technically speaking we could write them all the same. What?? Because they are actually linguistically speaking in complementary distribution with each other.

Think about it.

Do you ever say ch+iang or q+ang? Or q+an or ch+ian? Or pronounce ch+u with the German umlaut vowel ü, or q+u with the normal <u>? You never do!

The consonants <jqx> and <zh ch sh> are always followed by different vowels to each other. Knowing these vowels will help you tell them apart in listening, and aid you, eventually, in production.

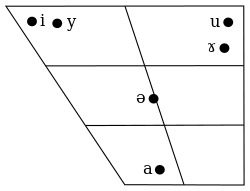

Look at this diagram below of standard Chinese monophthongs (single vowels). The pointy bit is the front of our mouth, and the lines represent height and ‘backness’. The dots are where the highest point of your tongue in your mouth is when you pronounce the vowel. We only need to worry about <u> and <y> for now.

The /u/ is the <u> we get after <zh ch sh> - e.g. chū. This is familiar to most people with knowledge of Romance languages - it’s a long, clear sound without any change of the vowel (careful native English speakers; we’re not very good at this one). The /y/ is the German <ü> or French <u>.

The /I/ here is the high ‘ee’ sound that we get in qi, ji, xi etc. This sound doesn’t exist after <zh ch sh>, but also <s r>. Instead, we have what’s often analysed as a ‘syllabic consonant’ - if you think about it, there really isn’t much ‘vowel’ in 是 shì or 日 rì. The first is just a long <shhh> sound - but this is a complex topic best left for another day.

Why do we get the high sounds (if you make the sounds in your mouth, you can feel that ‘eeee’ and ‘üüü’ move your tongue higher up than the other two) after the alveolo-palatal consonants and not the others? If you remember, <y> or /j/ as in ‘yes’ is a palatal consonant. This sound is actually incredibly similar to that high ‘eee’ - try saying ‘eee’ and then ‘ehhh’ (as in ‘yes’) and notice that when you switch vowel, you automatically say a <y> sound without even trying. If you are making a palatal sound like <y>, or like <j q x>, your tongue is already in the position to make <ü> and high ‘ee’ very easily. And humans are lazy - it’s much easier to follow a consonant with a vowel that’s in the same place, than to change the place completely. Technically speaking this is called ‘ease of articulation’. So when we want to say <qu>, the <u> gains some of the characteristics and is pronounced more similarly to the <q>.

And if you think about the rest of the pinyin table - this pattern of <q j x> being associated with ‘high’ vowels doesn’t stop with <u> and <i>. You get <chang>, but you don’t get <*qang> (* means ‘wrong’), but <qiang> with an extra palatal <y> /j/ sound in there. You get <zhang>, but not <*jang>, but <jiang>. You get <shang> but <xiang> etc etc. There are essentially no overlapping areas where only the consonants and different, but the vowels are the same. This is hugely helpful for learning to recognise the difference between the two sets of consonants, and also for people understanding you, the terrible, unforgivable second language learner - since there are no contexts in which the two sets can be confused with each other, as long as you pronounce the vowel afterwards correctly, what you want to say should be clear.

With that in mind, let’s get onto the actual pronunciation!

This is where you want to pronounce <x>. It’s similar to, but not quite the same as, the German palatal fricative written <ch> as in ‘ich’ (NOT as in ‘ach’), so if you have this sound in your inventory, you’re already winning! When you pronounce <sh>, the body of the tongue (the middle bit) is sunk down quite low; when you pronounce <x>, you need to raise the tongue towards your palate (the ‘palatal’ bit of the sound) and bring the front of your tongue under the back of your teeth, almost like you’re going to whistle. It’s helpful for all of these to put your tongue behind your lower front teeth, though you can also make the sound with it behind your upper front teeth as in the diagram below.

When you say <x>, without any vowels following it, it should sound higher pitched, and your lips should be spread wide. When you say <sh>, it sounds lower pitched and your lips are not stretched - in fact, they’re bunched. Watch videos of native speakers pronouncing them in isolation, and try to copy their mouth shapes.

<j> vs <q>

Most people can get away with some approximation of <x> because of the difference in vowel sounds, and while it may be wrong, if the rest of your pronunciation is ok, it won’t make a huge difference to people’s understanding of you. Many people, however, struggle hugely with <q> and <j> - and there’s no handy vowels to tell these apart.

First: Chinese doesn’t make the distinction between voiced and voiceless consonants like many languages like Spanish or Russian, but instead between non-aspirated and aspirated consonants, a little like English. This means that English natives often actually sound more natural when they are pronouncing te de or bo po than other foreigners. For speakers of languages without this aspiration difference (the difference between a consonant with a puff of air and without), this is difficult to get used to, but doesn’t usually cause difficulties with comprehension. What it does mean, though, is that the biggest difference between <q> and <j> is aspiration - <q> is aspirated, while <j> is not. Hold out your hand and try to feel the difference. You should feel a thin stream of air hit your hand in consonants like <t p q>.

Youtube for practicing:

Grace Mandarin - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05BMKdxHjp8 Mandarin Blueprint - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxIL11PcNXE Yoyo Chinese - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_K1RTPxWiI0

BUT - BUT IT’S STILL SO HARD!!! HOW CAN I MAKE IT EASIER??

Firstly, this vowel difference afterwards is incredibly important. Your pronunciation won’t be CORRECT if you only make this vowel difference, but it will go a LONG way towards helping you a) distinguish the correct pronunciation of other speakers, and b) copying them more accurately. What we’re all doing now, as second language learners or learners who have grown up without as much input as we’d like, is retraining our brain to the contrasts that are important. English doesn’t have a contrast between <q> and <ch>, or <sh> and <x>, so naturally if you’re a monolingual native English speaker it’s going to take some time. Be patient with yourselves. When we’re very young babies, we can make a difference between all phonemic distinctions in the world. And then at about 10 months we just lose that ability essentially instantly, because we’ve already established which contrasts are important and which aren’t. That’s not to say kids can’t learn it - because they clearly do - or adults can’t, but that you are LITERALLY RETRAINING YOUR BRAIN.

It’s not just about where to put your tongue, how to shape your mouth. Our brains are effective - they only store which information is necessary for the language, nothing extraneous. Technically speaking the /k/ in <kit> and <car> are two very different sounds, and in some languages they count as different phonemes and are written with different letters - but you probably never even noticed they were different at all! Because in English, all the extra information that says ‘this sound is pronounced more palatal’ and ‘this sound is pronounced more velar’ just doesn’t matter. So when you’re trying to learn these contrasts that don’t exist in your native language, it doesn’t matter if you can make the sound correctly once. What you actually need to do is convince your brain that every single time you hear or pronounce <j q x zh ch sh> you need to pay attention to contrast it previously filed under ‘not important’.

Lastly: be kind to yourself!!!

This takes babies about 10 months to get down - 10 months of solid, constant input with caregivers that are very focused on them. And you’re fighting how your brain has wired itself to disregard that contrast. How can you fix this? Input. INPUT IS KING. You need to present your brain with enough Chinese, enough different voices and speakers, to make it realise that there’s a crucial, important difference between all <qiang> and <chang> and so on. This will take time, but as long as you have enough input you’ll get there. But be kind to yourself. YOU ARE RESHAPING YOUR BRAIN.

加油!

- 梅晨曦

#pronunciation#chinese#chinese langblr#chinese studyblr#chinese pronunciation#pinyin#langblr#studyblr#linguistics#lingblr#phonetics#phonology#tongueblr#polyglot#hate this tagging game but guess it's gotta be done

177 notes

·

View notes