#wedding abaya

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

At EastEssence, we offer a stunning collection of wedding abayas that blend elegance with tradition. Our designs draw inspiration from diverse cultures such as Arabic, Pakistani, Moroccan, African, and Indian, celebrating the beauty of Islamic fashion. Each wedding abaya is carefully crafted with luxurious fabrics, intricate details, and modest silhouettes to ensure brides look graceful and stylish on their special day. Embrace the perfect fusion of tradition and modernity with EastEssence's wedding abayas.

0 notes

Text

#arabic attire#wedding#wedding dress#kaftans#abaya wedding dresses#Chiffon Embroidery Moroccan kaftan#Moroccan Islamic Wedding Caftan#islamic wedding dresses

1 note

·

View note

Text

Title : Eid abayas Dubai

Discover our stunning collection of Eid abayas in Dubai at Couture365. Elevate your style this holiday season with our luxurious designs. Shop now.

0 notes

Text

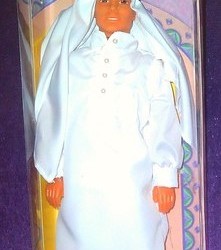

Finding information on Jamila wasn't particularly easy, but from what I can gather...

(credit to @eepop-stuffs btw for getting her on my radar!)

Jamila was first released in 2006 by Simba Toys Middle East. According to an article published upon her debut at the 2006 Middle East Toy Fair in Dubai, her prototype initially intended to include fashions representing Turkey, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. However, these concepts never made it to final release, and we unfortunately have no photos of what they would have looked like.

Her initial lineup consisted of four dolls: herself, her male Arabic friend Jamil, her Indian friend Sunayana, and her Egyptian friend Kareema.

The name Jamila means "beautiful", and she seems to have only really been released with one outfit. She wore a black abaya with silver detailing with black shoes, and underneath wore a light blue tanktop with a white pencil skirt. Like her friends Sunayana and Kareema, Jamila has dark hair, brown eyes, and henna on her hands and feet.

(Credit to Bababolond on Flickr for the images)

For those unaware, Henna is a form of body decoration which originated from Africa and the Middle East, used with a natural dye from the Mehendi (lawsonia inermis). It is commonly tied to religious ceremonies such as engagements, weddings, Diwali, and Eid!

For Eid Al-Fitr, Henna would be applied towards the end of Ramadan as a symbol of the earthly delight of being alive. Jamila (and Sunayana if we're to believe they had identical Henna) seems to have eye imagery in hers, which represents protection from evil thoughts or wishes. It's also found on the top of her hands, also symbolizing protection, and on her feet, meant to soothe the nerves.

The name Jamil means "handsome". Jamil was initially released clean-shaven, but it seems later releases gave him facial hair. This might have been around the same time he was changed from Jamila's male friend to her husband, likely because (although opposite-sex friendships aren't explicitly forbidden) certain Muslims worry such friendships might result in inappropriate romantic thoughts. While this doesn't seem to be a unanimous belief across the board (many believing opposite-sex friendships are fine so long as you're careful), it might have caused enough controversy that Simba felt the need to marry the two so there weren't any implications. (Credit to Jan Unwichtig and Bababolond on Flickr for the images)

Ngl tho he is giving me major Kenergy...

Jamil comes with a white Thobe with silver buttons, a white Serwal ( undergarments traditionally worn beneath the Thobe), a white cotton undershirt, a white headscarf known as a Ghutra (tied with a black band called the Egal), black sandals, and a small dagger.

I'm actually not sure why his doll comes with a knife? The closest I could find was the Kirpan: a knife or sword which serves as a reminder to promote justice and protect the weak, mandatory for Amritdhari Sikhs to wear at all times. However, although non-Muslims sometimes confuse the two, Sikhism is a completely separate religion from Islam.

If anyone knows what this knife might be intended to represent, please let me know and I'll reblog an edit to this post!

After they were married, Jamila and Jamil had two children: Asad (meaning "Lion") and Almira (meaning "Princess"), both seen in the first illustration on this post. However, I can only seem to find one doll release for their daughter Almira, and none for Asad. Jamila comes in this playset in her base outfit, while her daughter (who cries when you press her stomach) wears pink pajamas. The playset includes a crib and several plastic accessories, including two hair brushes, a blow drier, and a baby bottle. Not only is this only release for Almira, but this also seems to be the only other release for Jamila aside from her initial core doll.

Sunayana means "woman with lovely eyes". She has long braided black hair, wearing a blue Lehenga Choli with a yellow Dupatta. Like Jamila, she also has henna on her hands and feet. She wears silver bangles, a silver necklace, and what I believe might be a Maang Tikka. Based on her images on the back of the doll boxes, I'm fairly certain she came wearing yellow sandal heels as well!

Honestly she might be one of my favorites of the line, since you sadly don't see many culturally-accurate Indian dolls compared to other ethnic groups. I especially love the use of color, and just how much jewelry she comes with!

Finally we have Jamila's Egyptian friend Kareema, whose name means "generous" or "kind". She has pale pink undergarments painted on beneath her clothes, which I assume Jamila has as well. Weirdly enough, however, she doesn't seem to have Henna like the other two.

Like Sunayana and Jamila she has long black hair, which is kept beneath a white hijab. She wears a long blue overcoat, matching jeans, blue shoes, and a multicolored striped shirt. As far as I can tell, her clothing doesn't seem to have Egyptian cultural roots like Sunayana's has Indian, however her modest style of dress and hijab are common for most Muslim women.

I've been meaning to make this post for at least a full week, and it's nice to finally get to share another beautiful yet obscure Muslim doll! It's a shame this doll didn't have more releases, since I'm honestly curious with the direction the might have taken with her and her friends based on the prior illustration! Regardless, I'm happy I got to share her and her friends with you all :)

Ramadan Kareem!

#FUCKING FINALLY IVE BEEN WAITING FOR SO LONG TO POST THIS#dolls#dollblr#muslim dolls#jamila doll#simba toys#jamil doll#sunayana doll#kareema doll#long post

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey so taking advantage of your dune fashionposting while you’re still doing it, what do you think fremen would wear just sort of casually in the sietch? Because as much as i love the costume design for the movies, come ON denis they’re not just going to be in sad beige ALL THE TIME. Like yeah out in the desert sure camo makes sense, but at home when they’re not fully suited up, or for special occasions?? PATTERNS!! COLORS!! Obviously still stuff you can get from natural dyes but like come ON. Geez sorry this turned into a rant i’m sorry.

So obviously the typical abayas and thawbs, and other universal arabic clothing suited for a hot climate. But in particular, I always imagine the clothing of the Bedouin (the inspiration for the Fremen), the Tuareg, and other desert dwelling nomadic cultures. Relatively simple and loose garments, though they can still be customized and decorated, especially for important events like weddings and such.

#dune#I love you lightweight loose clothing that's been used for thousands of years by the ppl of the deserts#don't fix it if it aint broke

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I think princess Kate is the best dressed because western style clothes suit her amazingly, just like Japanese princesses look better with their kimonos, Rajwa shines in an abaya and let’s not forget how splendid Anisha looked wearing her traditional wedding attire. I just wish they would wear their national costume all the time ☺” - Submitted by Anonymous

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

random question (but i think you're bery smart and i would love your advice /opinion about this):

a lot of my friends are getting married and i am struggling a lot because i tried to wear dresses and i don't feel comfortable with them.

i think that it could help if i found the dresses interesting or fascinating. My ex is from Kolkata and she always shares with me all those beautiful saree and I ADORE THEM.

So an idea struck me: what if I wore a saree? I love them and I would feel safe because they remind me of my ex whom i still love and adore to this day.

But...would it be right to do that? I feel like I would be disrespectful since I don't really know the traditions or the culture that well.

What do you think?

I can't speak for all south asians, but I don't think it's offensive at all.

For eg, I think it would be offensive if I, as a non-muslim, wore an abaya, because it's not a costume you can try on. But I did cover my head with a shawl when I went to the mosques in Pakistan. So, it's about knowing what is respectful and what is not.

There are certain clothes, accessories, and jewelry in our culture that are not okay for other people to wear because they have religious significance. But I don't think it's the same for a saree.

In Sri Lanka, we love it when other people (including those from different ethnicities) wear our cultural clothes.

There are different ways to wear sarees depending on your ethnicity.

For eg, how a tamil person wears it (traditionally):

This is how a sinhalese person wears it traditionally

you can see the difference near the waist, blouse, and pleats.

what we (and any culture) would consider offensive is when other cultures take ownership of your own and try to erase it. For eg, there was a whole thing on tiktok/insta recently where some white women were discovering desi dupattas (shawls) and calling them 'bohemian chic/scandinavian scarves) - which pissed people off (rightfully so).

I think it's totally fine for you to wear a saree as long you call it what it is :)

I hope you find some beautiful sarees to wear for the wedding. There are so many different styles and fabrics and designs. I'm sure you will find something that makes you feel comfortable <3

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

We meet again, Bohol!

As beautiful as the Philippines is, many destinations offer mostly sand and surf. But not Bohol. This province is known for unique attractions that you can’t find anywhere else in the Philippines.

Sure, other islands in the Philippines are worth recommending, too, but most boast one or two of the following — white beaches, incredible sites, diverse wildlife, interesting history. Bohol has them all. From wild encounters with dolphins and tarsiers to the incomparable views of the Chocolate Hills, Bohol is a province that is easy to promote. It doesn’t need much sales talk.

We stayed at Coastal View in Panglao, then we transferred to On Board Beach Hostel and Resort for some quiet alone time near the beach. The wedding was at South Palms Resort, and I can attest that this is probably the most exquisite hotel here, next to Bohol Beach Club.

I was tasked with the daunting task of speaking in front of everyone. I wasn't really prepared to cry, so I let the "funny" me take over. Let me share to you guys my speech during the wedding.

"Kamusta naman ang lahat? Nakainom na ba? Kung Hindi pa, ito na yung time. Haha. For everyone's reference, I'm jasfher ako yung favorite friend ng groom and bride. Jk. Haha.

Nung sinabi nila na magssppeech ako, siyempre napressure ako kasi hello 'di ko naman sila close? Ano sasabihin ko dito? Jk. Haha

Okay kidding aside, sige maybe I'll just start ho I met the bride and the groom. Tagalog yung speech ko so pasensya na. To our foreigner friends, welcome to the Philippines. Haha.

Si brux and karla orgmates ko from UP travel society. Hindi ko din alam paano nabuo yung barkadahan namin, pero I guess we all just clicked and nagkakaayaan na lang kumain, gumala, tumambay ganyan, and the rest was history. So kwentuhan ko na lang kayo muna ng mga misadventures namin para may pulot naman kayo sa speech ko. Haha.

Sa mga travel namin, si karla isa sa mga main organizer, tapos si brux ang aming walking calculator. Sa tamad naming magcompute, si brux na bahala sa hatian, feel namin nagogoyo kami minsan, pero okay lang kasi wala naman kami nung math skills niya. Haha.

Nung nasa adventurous era pa kami, ang bonding namin ay umakyat ng bundok. Nagbuwis buhay trip kami sa Mt. pamitinan, tapos nagpapicture sa crater ng Taal, nakiparty sa Malasimbo sa Puerto Galera with hindi namin kilala, nagbackpacking kami 8 days sa Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand na natutulog sa bus dala bagahe, kumain ng scorpion at tarantula, kumain ng happy pizza, nagtemple hopping sa Angkor Wat at sa mga temples sa Thailand, tapos nag 8 days din kami sa Bali, Indonesia ewan ko din paano namin napupull off pero napakadami naming pinupuntahan tapos wala ako sa organizing committee so ang ambag ko talaga ay chumika at magpicture. Haha.

pero sa mga local travel namin, dalawa yung pinaka favorite ko: yung 1) Siargao at yung 2) South cotabato. Yung siargao kasi grabe talaga yun gabi-gabi kami lasing as in tumatakbo kami nina karla sa kalsada tapos hinahabol kami nina brux. Haha. Dun ko din naranasan maghanap ng GoPro sa dagat ng nakaflashlight lang kasi nalaglag nung nagsurfing kami. Grabe talaga yun. Nung South Cotabato naman, natry namin yung highest zipline in the South East Asia, may nadaanan kaming apat na waterfalls ganun kataas. Tapos ang dami naming change costume nag T'boli traditional costume kami, tapos nag abaya and hijab kami nung pumunta kaming Grand Mosque. Very dubai ganon. Haha.

Favorite memory ko sa kanila ay every travel namin, nagsusulatan sila ng postcards. Sabi ko grabe couple goals. Indeed a matchmake in heaven walang distance distance. They will really make way to communicate, and show their love for each other. The yin to each other's yang.

So medyo ang haba na no? haha so summary and summary? Haha. Nakita ko silang nag grow, both literally and figuratively. As in kung may masasabi akong couple na tested by time and distance ay sila talaga iyon. Proud na proud ako tbh na nakakakilala ako ng mga taong kasing galing niyo. sobrang supportive niyong friends, sweet, thoughtful, funny, smart, witty, amazing lahat na. In between those laughters, I know genuine love is there. Sobrang happy ko na nagkatuluyan kayo, and from day 1, alam kong kayo na talaga. I know madaming taon taon pa tayong pagsasamahan, at andito lang kami para sa inyo. Congratulations, Karla and Brux, and i only hope the best for you both. Mahal na mahal ko kayo 💕

Cheers to the brucals!" Probably the best and most heartfelt wedding I've been to. Cryfest. Literally shed buckets of tears. So this is how it feels like to see your close friends get married. I was so lucky to have witnessed this momentous event in our barkada (god and tanda na namin haha)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nazneen front back contrast hand embroidery party wear Kaftan

buy from- https://www.nazneen.in/wedding-abaya-online-collection-shop/Nazneen-front-back-contrast-hand-embroidery-party-wear-Kaftan

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wedding dress#muslimah #abaya #hijab #trending #youtubeshorts #viral

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

06.2024

Journal #3

Oh to spread my wings and fly away

Recently I've been stressed and escaping into my dream world to give myself a slight break. Trying to ensure that i have a work-school-life balance has been a bit difficult as one always bleeds into another. Recently I was planning an event for July but due to how things have been going at my job, but I think I’m going to make it an August event instead. Accounting has been hard and my professor hasn’t been the best in the communication department. I just want the month to be over and pass accounting since the math is breaking my brain ㅠㅠ. While doing all of this I’m scrambling to find the last few pieces of the outfit that I’m wearing to a wedding that’s quickly approaching. I just need a cool break. Wish me luck ㅠㅠ

To-do List:

- Staycation (DC)

- Dinner with CEI

- Buy an Abaya

- Pack for Canada (6/16)

- Email new hires

- Study for ACCT 212 Exam One

- Do my hair

- Buy new perfumes

- Get my eyebrows threaded

[ I bought my first camo skirt, and ngl it’s warming up on me😌 ]

#adulting#college student#lifeblogging#lifeblr#mental health#romantizing life#spotify#full time jobs#selfiie#to do list#café#flowers#cat#black tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

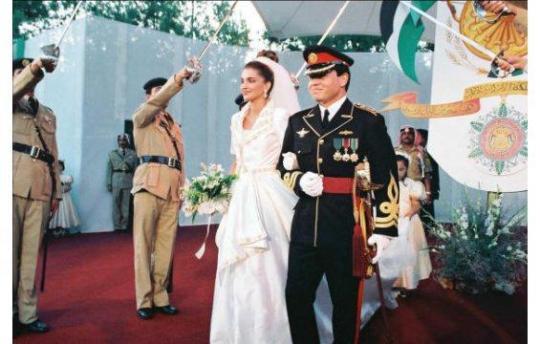

Wedding predictions :

What will Rajwa and Hussein wear for their wedding?

Flash back to King Abdullah and Queen Rania's wedding:

King Abdullah: wore a uniform + hat.

Queen Rania: wore a "then modern" 😛 wedding dress.

Flash back to Prince Hamza who was a crown prince at the time:

Prince Hamza : a uniform + shamegh.

Princess Noor: A dress that seemed traditional and modern at the same time. One thing's for sure Noor dressed conservatively.

Now my guess is :

Hussein :

Something like this : A uniform + Shamegh ( Like Prince Hamza )

A lil bit of history: King Abdullah is born to a British mother , he went to a boarding school at a very young age in England I think, then he attended highschool in the US. Anyway, when he ascended the throne he couldn't speak Arabic fluently and people used to mock him ( I felt sorry for that). But, Jordanians wanted a ruler who was as "arabic and conservative" as they are ( that's their right ) anyway that's why king Abdullah had always emphasized on the fact that he is an Arab.

Also, Jordanian people like Hamzah because he seems more traditional and they hate the fact that Abdullah is more westernized .

So

For sure Hussein's gonna wear something that emphasizes on the fact that he's an Arab and better if it highlights the fact that he is Jordanian => Shamegh.

OR

There's another card to play :

People loved " King Hussein" and the Jordanian Royal Family has always insisted on the fact that prince Hussein resembles his grandfather both in looks and character.So maybe Prince Hussein will wear => A uniform that's a lil bit inspired by his grandfather's.

One thing's for sure there's gonna be a sword and I like that!!!

Rajwa :

Euh, for her engagement she wore a abaya " that's traditional" and conservative yet timeless all at the same time.

On the back of the abaya there was a romantic and special message : Two birds "two lovers" united with the continuation of their chest.

So

My predictions: A mix between traditional and modern => timless dress with a special message that highlites her Saudi Origins.

A little bit of history: The hashemites had ruled "Mecca" ( Saudi Arabia) continuously from the 10th century. The hashemites are historically linked to Saudi Arabia.

Or

Given that people are criticizing the fact that Rajwa had a westernized lifestyle in the past and that the royal family are trying to portray her as a conservative girl. So in order not to seem hypocrite => The wedding dress will be modern YET designed by an Arabic designer. ( Elie Saab / Zuhair Murad/ Azzedine Alaïa )

Ofc , in this case it's gonna be bespoke and conservative!

Wedding dresses by Elie Saab and Zuhair Murad.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here is a critique: Argue all you want with many feminist policies, but few quarrel with feminism’s core moral insight, which changed the lives (and minds) of women forever: that women are due the same rights and dignity as men. So, as news of the appalling miseries of women in the Islamic world has piled up, where are the feminists? Where’s the outrage? For a brief moment after September 11, when pictures of those blue alien-creaturely shapes in Afghanistan filled the papers, it seemed as if feminists were going to have their moment. And in fact the Feminist Majority, to its credit, had been publicizing since the mid-90s how Afghan girls were barred from school, how women were stoned for adultery or beaten for showing an ankle or wearing high-heeled shoes, how they were prohibited from leaving the house unless accompanied by a male relative, how they were denied medical help because the only doctors around were male.

But the rest is feminist silence. You haven’t heard a peep from feminists as it has grown clear that the Taliban were exceptional not in their extreme views about women but in their success at embodying those views in law and practice. In the United Arab Emirates, husbands have the right to beat their wives in order to discipline them—“provided that the beating is not so severe as to damage her bones or deform her body,” in the words of the Gulf News. In Saudi Arabia, women cannot vote, drive, or show their faces or talk with male non-relatives in public. (Evidently they can’t talk to men over the airwaves either; when Prince Abdullah went to President Bush’s ranch in Crawford last April, he insisted that no female air-traffic controllers handle his flight.) Yes, Saudi girls can go to school, and many even attend the university; but at the university, women must sit in segregated rooms and watch their professors on closed-circuit televisions. If they have a question, they push a button on their desk, which turns on a light at the professor’s lectern, from which he can answer the female without being in her dangerous presence. And in Saudi Arabia, education can be harmful to female health. Last spring in Mecca, members of the mutaween, the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue, pushed fleeing students back into their burning school because they were not properly covered in abaya. Fifteen girls died.

You didn’t hear much from feminists when in the northern Nigerian province of Katsina a Muslim court sentenced a woman to death by stoning for having a child outside of marriage. The case might not have earned much attention—stonings are common in parts of the Muslim world—except that the young woman, who had been married off at 14 to a husband who ultimately divorced her when she lost her virginal allure, was still nursing a baby at the time of sentencing. During her trial she had no lawyer, although the court did see fit to delay her execution until she weans her infant.

You didn’t hear much from feminists as it emerged that honor killings by relatives, often either ignored or only lightly punished by authorities, are also commonplace in the Muslim world. In September, Reuters reported the story of an Iranian man, “defending my honor, family, and dignity,” who cut off his seven-year-old daughter’s head after suspecting she had been raped by her uncle. The postmortem showed the girl to be a virgin. In another family mix-up, a Yemeni man shot his daughter to death on her wedding night when her husband claimed she was not a virgin. After a medical exam revealed that the husband was mistaken, officials concluded he was simply trying to protect himself from embarrassment about his own impotence. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, every day two women are slain by male relatives seeking to avenge the family honor.

The savagery of some of these murders is worth a moment’s pause. In 2000, two Punjabi sisters, 20 and 21 years old, had their throats slit by their brother and cousin because the girls were seen talking to two boys to whom they were not related. In one especially notorious case, an Egyptian woman named Nora Marzouk Ahmed fell in love and eloped. When she went to make amends with her father, he cut off her head and paraded it down the street. Several years back, according to the Washington Post, the husband of Zahida Perveen, a 32-year-old pregnant Pakistani, gouged out her eyes and sliced off her earlobe and nose because he suspected her of having an affair.

In a related example widely covered last summer, a teenage girl in the Punjab was sentenced by a tribal council to rape by a gang that included one of the councilmen. After the hour-and-a-half ordeal, the girl was forced to walk home naked in front of scores of onlookers. She had been punished because her 11-year-old brother had compromised another girl by being been seen alone with her. But that charge turned out to be a ruse: it seems that three men of a neighboring tribe had sodomized the boy and accused him of illicit relations—an accusation leading to his sister’s barbaric punishment—as a way of covering up their crime.

Nor is such brutality limited to backward, out-of-the-way villages. Muddassir Rizvi, a Pakistani journalist, says that, though always common in rural areas, in recent years honor killings have become more prevalent in cities “among educated and liberal families.” In relatively modern Jordan, honor killings were all but exempt from punishment until the penal code was modified last year; unfortunately, a young Palestinian living in Jordan, who had recently stabbed his 19-year-old sister 40 times “to cleanse the family honor,” and another man from near Amman, who ran over his 23-year-old sister with his truck because of her “immoral behavior,” had not yet changed their ways. British psychiatrist Anthony Daniels reports that British Muslim men frequently spirit their young daughters back to their native Pakistan and force the girls to marry. Such fathers have been known to kill daughters who resist. In Sweden, in one highly publicized case, Fadima Sahindal, an assimilated 26-year-old of Kurdish origin, was murdered by her father after she began living with her Swedish boyfriend. “The whore is dead,” the family announced.

As you look at this inventory of brutality, the question bears repeating: Where are the demonstrations, the articles, the petitions, the resolutions, the vindications of the rights of Islamic women by American feminists? The weird fact is that, even after the excesses of the Taliban did more to forge an American consensus about women’s rights than 30 years of speeches by Gloria Steinem, feminists refused to touch this subject. They have averted their eyes from the harsh, blatant oppression of millions of women, even while they have continued to stare into the Western patriarchal abyss, indignant over female executives who cannot join an exclusive golf club and college women who do not have their own lacrosse teams.

But look more deeply into the matter, and you realize that the sound of feminist silence about the savage fundamentalist Muslim oppression of women has its own perverse logic. The silence is a direct outgrowth of the way feminist theory has developed in recent years. Now mired in self-righteous sentimentalism, multicultural nonjudgmentalism, and internationalist utopianism, feminism has lost the language to make the universalist moral claims of equal dignity and individual freedom that once rendered it so compelling. No wonder that most Americans, trying to deal with the realities of a post-9/11 world, are paying feminists no mind.

To understand the current sisterly silence about the sort of tyranny that the women’s movement came into existence to attack, it is helpful to think of feminisms plural rather than singular. Though not entirely discrete philosophies, each of three different feminisms has its own distinct reasons for causing activists to “lose their voice” in the face of women’s oppression.

The first variety—radical feminism (or gender feminism, in Christina Hoff Sommers’s term)—starts with the insight that men are, not to put too fine a point upon it, brutes. Radical feminists do not simply subscribe to the reasonable-enough notion that men are naturally more prone to aggression than women. They believe that maleness is a kind of original sin. Masculinity explains child abuse, marital strife, high defense spending, every war from Troy to Afghanistan, as well as Hitler, Franco, and Pinochet. As Gloria Steinem informed the audience at a Florida fundraiser last March: “The cult of masculinity is the basis for every violent, fascist regime.”

Gender feminists are little interested in fine distinctions between radical Muslim men who slam commercial airliners into office buildings and soldiers who want to stop radical Muslim men from slamming commercial airliners into office buildings. They are both examples of generic male violence—and specifically, male violence against women. “Terrorism is on a continuum that starts with violence within the family, battery against women, violence against women in the society, all the way up to organized militaries that are supported by taxpayer money,” according to Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, who teaches “The Sexuality of Terrorism” at California State University in Hayward. Violence is so intertwined with male sexuality that, she tells us, military pilots watch porn movies before they go out on sorties. The war in Afghanistan could not possibly offer a chance to liberate women from their oppressors, since it would simply expose women to yet another set of oppressors, in the gender feminists’ view. As Sharon Lerner asserted bizarrely in the Village Voice, feminists’ “discomfort” with the Afghanistan bombing was “deepened by the knowledge that more women than men die as a result of most wars.”

If guys are brutes, girls are their opposite: peace-loving, tolerant, conciliatory, and reasonable—“Antiwar and Pro-Feminist,” as the popular peace-rally sign goes. Feminists long ago banished tough-as-nails women like Margaret Thatcher and Jeanne Kirkpatrick (and these days, one would guess, even the fetching Condoleezza Rice) to the ranks of the imperfectly female. Real women, they believe, would never justify war. “Most women, Western and Muslim, are opposed to war regardless of its reasons and objectives,” wrote the Jordanian feminist Fadia Faqir on OpenDemocracy.net. “They are concerned with emancipation, freedom (personal and civic), human rights, power sharing, integrity, dignity, equality, autonomy, power-sharing [sic], liberation, and pluralism.”

Sara Ruddick, author of Maternal Thinking, is perhaps one of the most influential spokeswomen for the position that women are instinctually peaceful. According to Ruddick (who clearly didn’t have Joan Crawford in mind), that’s because a good deal of mothering is naturally governed by the Gandhian principles of nonviolence such as “renunciation,” “resistance to injustice,” and “reconciliation.” The novelist Barbara Kingsolver was one of the first to demonstrate the subtleties of such universal maternal thinking after the United States invaded Afghanistan. “I feel like I’m standing on a playground where the little boys are all screaming ‘He started it!’ and throwing rocks,” she wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “I keep looking for somebody’s mother to come on the scene saying, ‘Boys! Boys!’ ”

Gender feminism’s tendency to reduce foreign affairs to a Lifetime Channel movie may make it seem too silly to bear mentioning, but its kitschy naiveté hasn’t stopped it from being widespread among elites. You see it in widely read writers like Kingsolver, Maureen Dowd, and Alice Walker. It turns up in our most elite institutions. Swanee Hunt, head of the Women in Public Policy Program at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government wrote, with Cristina Posa in Foreign Policy: “The key reason behind women’s marginalization may be that everyone recognizes just how good women are at forging peace.” Even female elected officials are on board. “The women of all these countries should go on strike, they should all sit down and refuse to do anything until their men agree to talk peace,” urged Ohio representative Marcy Kaptur to the Arab News last spring, echoing an idea that Aristophanes, a dead white male, proposed as a joke 2,400 years ago. And President Clinton is an advocate of maternal thinking, too. “If we’d had women at Camp David,” he said in July 2000, “we’d have an agreement.”

Major foundations too seem to take gender feminism seriously enough to promote it as an answer to world problems. Last December, the Ford Foundation and the Soros Open Society Foundation helped fund the Afghan Women’s Summit in Brussels to develop ideas for a new government in Afghanistan. As Vagina Monologues author Eve Ensler described it on her website, the summit was made up of “meetings and meals, canvassing, workshops, tears, and dancing.” “Defense was mentioned nowhere in the document,” Ensler wrote proudly of the summit’s concluding proclamation—despite the continuing threat in Afghanistan of warlords, bandits, and lingering al-Qaida operatives. “[B]uilding weapons or instruments of retaliation was not called for in any category,” Ensler cooed. “Instead [the women] wanted education, health care, and the protection of refugees, culture, and human rights.”

Too busy celebrating their own virtue and contemplating their own victimhood, gender feminists cannot address the suffering of their Muslim sisters realistically, as light years worse than their own petulant grievances. They are too intent on hating war to ask if unleashing its horrors might be worth it to overturn a brutal tyranny that, among its manifold inhumanities, treats women like animals. After all, hating war and machismo is evidence of the moral superiority that comes with being born female.

Yet the gender feminist idea of superior feminine virtue is becoming an increasingly tough sell for anyone actually keeping up with world events. Kipling once wrote of the fierceness of Afghan women: “When you’re wounded and left on the Afghan plains/And the women come out to cut up your remains/Just roll to your rifle and blow out your brains.” Now it’s clearer than ever that the dream of worldwide sisterhood is no more realistic than worldwide brotherhood; culture trumps gender any day. Mothers all over the Muslim world are naming their babies Usama or praising Allah for their sons’ efforts to kill crusading infidels. Last February, 28-year-old Wafa Idris became the first female Palestinian suicide bomber to strike in Israel, killing an elderly man and wounding scores of women and children. And in April, Israeli soldiers discovered under the maternity clothes of 26-year-old Shifa Adnan Kodsi a bomb rather than a baby. Maternal thinking, indeed.

The second variety of feminism, seemingly more sophisticated and especially prevalent on college campuses, is multiculturalism and its twin, postcolonialism. The postcolonial feminist has even more reason to shy away from the predicament of women under radical Islam than her maternally thinking sister. She believes that the Western world is so sullied by its legacy of imperialism that no Westerner, man or woman, can utter a word of judgment against former colonial peoples. Worse, she is not so sure that radical Islam isn’t an authentic, indigenous—and therefore appropriate—expression of Arab and Middle Eastern identity.

The postmodern philosopher Michel Foucault, one of the intellectual godfathers of multiculturalism and postcolonialism, first set the tone in 1978 when an Italian newspaper sent him to Teheran to cover the Iranian revolution. As his biographer James Miller tells it, Foucault looked in the face of Islamic fundamentalism and saw . . . an awe-inspiring revolt against “global hegemony.” He was mesmerized by this new form of “political spirituality” that, in a phrase whose dark prescience he could not have grasped, portended the “transfiguration of the world.” Even after the Ayatollah Khomeini came to power and reintroduced polygamy and divorce on the husband’s demand with automatic custody to fathers, reduced the official female age of marriage from 18 to 13, fired all female judges, and ordered compulsory veiling, whose transgression was to be punished by public flogging, Foucault saw no reason to temper his enthusiasm. What was a small matter like women’s basic rights, when a struggle against “the planetary system” was at hand?

Postcolonialists, then, have their own binary system, somewhat at odds with gender feminism—not to mention with women’s rights. It is not men who are the sinners; it is the West. It is not women who are victimized innocents; it is the people who suffered under Western colonialism, or the descendants of those people, to be more exact. Caught between the rock of patriarchy and the hard place of imperialism, the postcolonial feminist scholar gingerly tiptoes her way around the subject of Islamic fundamentalism and does the only thing she can do: she focuses her ire on Western men.

The most impressive signs of an indigenous female revolt against the fundamentalist order are in Iran. Over the past ten years or so, Iran has seen the publication of a slew of serious journals dedicated to the social and political predicament of Islamic women, the most well known being the Teheran-based Zonan and Zan, published by Faezah Hashemi, a well-known member of parliament and the daughter of former president Rafsanjani. Believing that Western feminism has promoted hostility between the sexes, confused sex roles, and the sexual objectification of women, a number of writers have proposed an Islamic-style feminism that would stress “gender complementarity” rather than equality and that would pay full respect to housewifery and motherhood while also giving women access to education and jobs.

Attacking from the religious front, a number of “Islamic feminists” are challenging the reigning fundamentalist reading of the Qur’an. These scholars insist that the founding principles of Islam, which they believe were long ago corrupted by pre-Islamic Arab, Persian, and North African customs, are if anything more egalitarian than those of Western religions; the Qur’an explicitly describes women as the moral and spiritual equals of men and allows them to inherit and pass down property. The power of misogynistic mullahs has grown in recent decades, feminists continue, because Muslim men have felt threatened by modernity’s challenge to traditional arrangements between the sexes.

What makes Islamic feminism really worth watching is that it has the potential to play a profoundly important role in the future of the Islamic world—and not just because it could improve the lot of women. By insisting that it is true to Islam—in fact, truer than the creed espoused by the entrenched religious elite—Islamic feminism can affirm the dignity of Islam while at the same time bringing it more in line with modernity. In doing this, feminists can help lay the philosophical groundwork for democracy. In the West, feminism lagged behind religious reformation and political democratization by centuries; in the East, feminism could help lead the charge.

At the same time, though, the issue of women’s rights highlights two reasons for caution about the Islamic future. For one thing, no matter how much feminists might wish otherwise, polygamy and male domination of the family are not merely a fact of local traditions; they are written into the Qur’an itself. This in and of itself would not prove to be such an impediment—the Old Testament is filled with laws antithetical to women’s equality—except for the second problem: more than other religions, Islam is unfriendly to the notion of the separation of church and state. If history is any guide, there’s the rub. The ultimate guarantor of the rights of all citizens, whether Islamic or not, can only be a fully secular state.

To this end, the postcolonialist eagerly dips into the inkwell of gender feminism. She ties colonialist exploitation and domination to maleness; she might refer to Israel’s “masculinist military culture”—Israel being white and Western—though she would never dream of pointing out the “masculinist military culture” of the jihadi. And she expends a good deal of energy condemning Western men for wanting to improve the lives of Eastern women. At the turn of the twentieth century Lord Cromer, the British vice consul of Egypt and a pet target of postcolonial feminists, argued that the “degradation” of women under Islam had a harmful effect on society. Rubbish, according to the postcolonialist feminist. His words are simply part of “the Western narrative of the quintessential otherness and inferiority of Islam,” as Harvard professor Leila Ahmed puts it in Women and Gender in Islam. The same goes for American concern about Afghan women; it is merely a “device for ranking the ‘other’ men as inferior or as ‘uncivilized,’ ” according to Nira Yuval-Davis, professor of gender and ethnic studies at the University of Greenwich, England. These are all examples of what renowned Columbia professor Gayatri Spivak called “white men saving brown women from brown men.”

Spivak’s phrase, a great favorite on campus, points to the postcolonial notion that brown men, having been victimized by the West, can never be oppressors in their own right. If they give the appearance of treating women badly, the oppression they have suffered at the hands of Western colonial masters is to blame. In fact, the worse they treat women, the more they are expressing their own justifiable outrage. “When men are traumatized [by colonial rule], they tend to traumatize their own women,” Miriam Cooke, a Duke professor and head of the Association for Middle East Women’s Studies, told me. And today, Cooke asserts, brown men are subjected to a new form of imperialism. “Now there is a return of colonialism that we saw in the nineteenth century in the context of globalization,” she says. “What is driving Islamist men is globalization.”

It would be difficult to exaggerate the through-the-looking-glass quality of postcolonialist theory when it comes to the subject of women. Female suicide bombers are a good thing, because they are strong women demonstrating “agency” against colonial powers. Polygamy too must be shown due consideration. “Polygamy can be liberating and empowering,” Cooke answered sunnily when I asked her about it. “Our norm is the Western, heterosexual, single couple. If we can imagine different forms that would allow us to be something other than a heterosexual couple, we might imagine polygamy working,” she explained murkily. Some women, she continued, are relieved when their husbands take a new wife: they won’t have to service him so often. Or they might find they now have the freedom to take a lover. But, I ask, wouldn’t that be dangerous in places where adulteresses can be stoned to death? At any rate, how common is that? “I don’t know,” Cooke answers, “I’m interested in discourse.” The irony couldn’t be darker: the very people protesting the imperialist exploitation of the “Other” endorse that Other’s repressive customs as a means of promoting their own uniquely Western agenda—subverting the heterosexual patriarchy.

The final category in the feminist taxonomy, which might be called the world-government utopian strain, is in many respects closest to classical liberal feminism. Dedicated to full female dignity and equality, it generally eschews both the biological determinism of the gender feminist and the cultural relativism of the multiculti postcolonialist. Stanford political science professor Susan Moller Okin, an influential, subtle, and intelligent spokeswoman for this approach, created a stir among feminists in 1997 when she forthrightly attacked multiculturalists for valuing “group rights for minority cultures” over the well-being of individual women. Okin admirably minced no words attacking arranged marriage, female circumcision, and polygamy, which she believed women experienced as a “barely tolerable institution.” Some women, she went so far as to declare, “might be better off if the culture into which they were born were either to become extinct . . . or preferably, to be encouraged to alter itself so as to reinforce the equality of women.”

But though Okin is less shy than other feminists about discussing the plight of women under Islamic fundamentalism, the typical U.N. utopian has her own reasons for keeping quiet as that plight fills Western headlines. For one thing, the utopian is also a bean-counting absolutist, seeking a pure, numerical equality between men and women in all departments of life. She greets Western, and particularly American, claims to have achieved freedom for women with skepticism. The motto of the 2002 International Women’s Day—“Afghanistan Is Everywhere”—was in part a reproach to the West about its superior airs. Women in Afghanistan might have to wear burqas, but don’t women in the West parade around in bikinis? “It’s equally disrespectful and abusive to have women prancing around a stage in bathing suits for cash or walking the streets shrouded in burqas in order to survive,” columnist Jill Nelson wrote on the MSNBC website about the murderously fanatical riots that attended the Miss World pageant in Nigeria.

As Nelson’s statement hints, the utopian is less interested in freeing women to make their own choices than in engineering and imposing her own elite vision of a perfect society. Indeed, she is under no illusions that, left to their own democratic devices, women would freely choose the utopia she has in mind. She would not be surprised by recent Pakistani elections, where a number of the women who won parliamentary seats were Islamist. But it doesn’t really matter what women want. The universalist has a comprehensive vision of “women’s human rights,” meaning not simply women’s civil and political rights but “economic rights” and “socioeconomic justice.” Cynical about free markets and globalization, the U.N. utopian is also unimpressed by the liberal democratic nation-state “as an emancipatory institution,” in the dismissive words of J. Ann Tickner, director for international studies at the University of Southern California. Such nation-states are “unresponsive to the needs of [their] most vulnerable members” and seeped in “nationalist ideologies” as well as in patriarchal assumptions about autonomy. In fact, like the (usually) unacknowledged socialist that she is, the U.N. utopian eagerly awaits the withering of the nation-state, a political arrangement that she sees as tied to imperialism, war, and masculinity. During war, in particular, nations “depend on ideas about masculinized dignity and feminized sacrifice to sustain the sense of autonomous nationhood,” writes Cynthia Enloe, professor of government at Clark University.

Having rejected the patriarchal liberal nation-state, with all the democratic machinery of self-government that goes along with it, the utopian concludes that there is only one way to achieve her goals: to impose them through international government. Utopian feminists fill the halls of the United Nations, where they examine everything through the lens of the “gender perspective” in study after unreadable study. (My personal favorites: “Gender Perspectives on Landmines” and “Gender Perspectives on Weapons of Mass Destruction,” whose conclusion is that landmines and WMDs are bad for women.)

The 1979 U.N. Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), perhaps the first and most important document of feminist utopianism, gives the best sense of the sweeping nature of the movement’s ambitions. CEDAW demands many measures that anyone committed to democratic liberal values would applaud, including women’s right to vote and protection against honor killings and forced marriage. Would that the document stopped there. Instead it sets out to impose a utopian order that would erase all distinctions between men and women, a kind of revolution of the sexes from above, requiring nations to “take all appropriate measures to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women” and to eliminate “stereotyped roles” to accomplish this legislative abolition of biology. The document calls for paid maternity leave, nonsexist school curricula, and government-supported child care. The treaty’s 23-member enforcement committee hectors nations that do not adequately grasp that, as Enloe puts it, “the personal is international.” The committee has cited Belarus for celebrating Mother’s Day, China for failing to legalize prostitution, and Libya for not interpreting the Qur’an in accordance with “committee guidelines.”

Confusing “women’s participation” with self-determination, and numerical equivalence with equality, CEDAW utopians try to orchestrate their perfect society through quotas and affirmative-action plans. Their bean-counting mentality cares about whether women participate equally, without asking what it is that they are participating in or whether their participation is anything more than ceremonial. Thus at the recent Women’s Summit in Jordan, Rima Khalaf suggested that governments be required to use quotas in elections “to leapfrog women to power.” Khalaf, like so many illiberal feminist utopians, has no hesitation in forcing society to be free. As is often the case when elites decide they have discovered the route to human perfection, the utopian urge is not simply antidemocratic but verges on the totalitarian.

That this combination of sentimental victimhood, postcolonial relativism, and utopian overreaching has caused feminism to suffer so profound a loss of moral and political imagination that it cannot speak against the brutalization of Islamic women is an incalculable loss to women and to men. The great contribution of Western feminism was to expand the definition of human dignity and freedom. It insisted that all human beings were worthy of liberty. Feminists now have the opportunity to make that claim on behalf of women who in their oppression have not so much as imagined that its promise could include them, too. At its best, feminism has stood for a rich idea of personal choice in shaping a meaningful life, one that respects not only the woman who wants to crash through glass ceilings but also the one who wants to stay home with her children and bake cookies or to wear a veil and fast on Ramadan. Why shouldn’t feminists want to shout out their own profound discovery for the world to hear?

Perhaps, finally, because to do so would be to acknowledge the freedom they themselves enjoy, thanks to Western ideals and institutions. Not only would such an admission force them to give up their own simmering resentments; it would be bad for business.

The truth is that the free institutions—an independent judiciary, a free press, open elections—that protect the rights of women are the same ones that protect the rights of men. The separation of church and state that would allow women to escape the burqa would also free men from having their hands amputated for theft. The education system that would teach girls to read would also empower millions of illiterate boys. The capitalist economies that bring clean water, cheap clothes, and washing machines that change the lives of women are the same ones that lead to healthier, freer men. In other words, to address the problems of Muslim women honestly, feminists would have to recognize that free men and women need the same things—and that those are things that they themselves already have. And recognizing that would mean an end to feminism as we know it.

There are signs that, outside the academy, middlebrow literary circles, and the United Nations, feminism has indeed met its Waterloo. Most Americans seem to realize that September 11 turned self-indulgent sentimental illusions, including those about the sexes, into an unaffordable luxury. Consider, for instance, women’s attitudes toward war, a topic on which politicians have learned to take for granted a gender gap. But according to the Pew Research Center, in January 2002, 57 percent of women versus 46 percent of men cited national security as the country’s top priority. There has been a “seismic gender shift on matters of war,” according to pollster Kellyanne Conway. In 1991, 45 percent of U.S. women supported the use of ground troops in the Gulf War, a substantially smaller number than the 67 percent of men. But as of November, a CNN survey found women were more likely than men to support the use of ground troops against Iraq, 58 percent to 56 percent. The numbers for younger women were especially dramatic. Sixty-five percent of women between 18 and 49 support ground troops, as opposed to 48 percent of women 50 and over. Women are also changing their attitudes toward military spending: before September 11, only 24 percent of women supported increased funds; after the attacks, that number climbed to 47 percent. An evolutionary psychologist might speculate that, if females tend to be less aggressively territorial than males, there’s little to compare to the ferocity of the lioness when she believes her young are threatened.

Even among some who consider themselves feminists, there is some grudging recognition that Western, and specifically American, men are sometimes a force for the good. The Feminist Majority is sending around urgent messages asking for President Bush to increase American security forces in Afghanistan. The influential left-wing British columnist Polly Toynbee, who just 18 months ago coined the phrase “America the Horrible,” went to Afghanistan to figure out whether the war “was worth it.” Her answer was not what she might have expected. Though she found nine out of ten women still wearing burqas, partly out of fear of lingering fundamentalist hostility, she was convinced their lives had greatly improved. Women say they can go out alone now.

As we sink more deeply into what is likely to be a protracted struggle with radical Islam, American feminists have a moral responsibility to give up their resentments and speak up for women who actually need their support. Feminists have the moral authority to say that their call for the rights of women is a universal demand—that the rights of women are the Rights of Man.

my god this dude wrote the world’s worst thesis and sent it to the worst candidate possible (a muslim-born woman from the middle east that regularly talks about the issues feminists apparently never talk about)

#btw ive gotten several of these anti-feminist rant messages and eventually i will probably get bored of u and block u jsyk#i know these are all dumb copy pastas from reddit probably but i get enough msgs as is#anonymous#long post

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perfect Eid Outfit? Cream Arabian Open Abaya

Hey lovelies!

Are you ready to add a touch of elegance and sophistication to your wardrobe? Look no further than the timeless beauty of cream coloured abayas! Whether you're attending a special occasion or gearing up for Eid festivities, these heavenly hues are guaranteed to steal the spotlight.

There's something truly magical about cream-colored abayas. They exude an air of grace and femininity that's simply irresistible. Plus, they're incredibly versatile, making them the ultimate wardrobe staple for any fashion-forward modest dresser.

As we approach Eid, it's time to start thinking about our outfit choices for the big day. And let me tell you, a cream-colored abaya is an absolute must-have! Whether you're celebrating with family, friends, or both, this stunning piece is sure to make you feel like a true style queen.

What I love most about cream coloured abayas is their ability to elevate any look. Pair yours with delicate accessories and a statement clutch for a touch of glamour, or keep it simple and chic with minimalistic jewellery and a sleek bun. However you choose to style it, you're guaranteed to make a lasting impression.

But here's the best part: cream coloured abayas are perfect for any special occasion, not just Eid! Whether you're attending a wedding, a graduation ceremony, or a fancy dinner party, this versatile piece has got you covered. It's the epitome of timeless elegance, and it's sure to turn heads wherever you go.

So, if you're ready to make a statement and stand out from the crowd, why not add a cream coloured abaya to your wardrobe? Trust me, you won't regret it!

Until next time, stay fabulous!

XOXO,

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Pre-wedding, Rajwa style was much more interesting and nice. I remember a zara suit and her engagement abaya was really pretty, her glam was more tidy. I dont know what happened after the wedding but she looks frumpy now. The least she can do out of respect for the dignataries she meets is to look professional and put-together” - Submitted by Anonymous

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

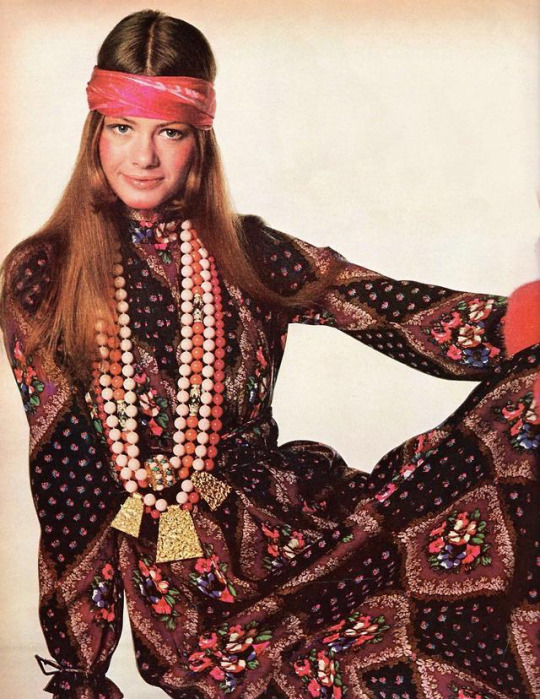

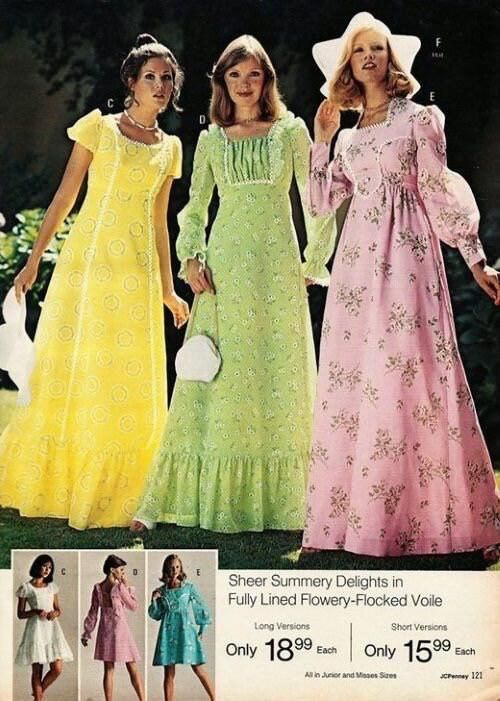

The 1970s - part 1

Some trends from the late 1960s carried through into the early 1970s, the Woodstock festival of peace and music marked the end of the 1960s hippie movement however, the hippie flower child look carried over into the first half of the decade in a non-restrictive bohemian silhouette with a heavy folksy influence.

Arts and crafts were very popular to the era, things such as tie-dye, batik, knitwear, crochet and macramé were present during this time and created a great sense of ease and comfort to early 1970s fashion.

1970s folk style.

Angelica Huston wearing Ossie Clark for Miss Selfridge, Cosmopolitan, May 1972

Designers like Laura Ashley and Jessica McClintock popularized the prairie dress phenomenon. The Prairie dress was typically made up of romantic silhouettes with delicate details like floral prints, long billowing skirts, and lots of ruffles.

Thea Porter

Thea Porter pioneered bohemian chic, her shop in Soho instantly drew a crowd of rock and film stars, clients such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd to Elizabeth Taylor, Faye Dunaway and Barbara Streisand took a liking to her style. Thea Porter celebrated ethnic styles in Indian style prints, free flowing breezy gauzy tent dresses and wide legged pants.

Thea Porter had seven signature looks:

the Abaya & Kaftan

the Gipsy dress

the Faye dress

the Brocade-panel dress

the Wrap-over dress

the Chazara jacket

Sirwal skirt

As well as this her fashion photography featured on the pages of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Women’s Wear

During the 1970s skirts could be seen in a variety of lengths, mini, midi or maxi. The maxi dress was a must have of the decade in a multitude of styles and shapes. Rich earthy tones dominated the era, warm browns, burgundy, rust, mustard, and avocado green took centre stage.

The 1970s saw women emerge in to the work place, they began to dress more "masculine" wearing pantsuits, day wear and separates echoed in the film'Annie Hall'. The image below shows Diane Keaton wearing a fitted vest with a collared white shirt and men’s neckties in the film.

From then on, the pantsuit became the next big thing. Bianca Jagger wore a YSL pantsuit at her wedding to Mick Jagger in 1971.

4 notes

·

View notes