#we were both painting over the same portrait to figure out his facial features and there was a hot second he looked like adam sandler

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

me and @merrimentforbidden gave my inquisitor a fresh coat of paint that almost led to a divorce, but he’s equal amounts of slimy and handsome now 👌

#my art#dragon age#dragon age inquisition#vincent trevelyan#we were both painting over the same portrait to figure out his facial features and there was a hot second he looked like adam sandler#it was disastrous

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paint Me Over

Disclaimer: I made and edited the gif I used for my header. That’s why I’ve posted this under the tag #btsgif. The footage belongs to BTS and BigHit, it’s obvs from one of Yoongi’s live streams. I also pulled the pic below from that footage. Feel free to use however you like, just please give me credit for the edit. Thanks 💜

I got this request on my Twitter account from @TheGirlInTheFloppyHat⁷ who said, “Soft stans please don't attack me, but a good looking guy, in a beret, casually rolling up his sleeves and painting away is hot as hell!!! HOT AS HELL!! 🔥 🔥 🔥 (Also, Yoongi the Renaissance Painter... Someone please take up the FanFic idea! 🤭🙈)”

Obviously, this is me volunteering to take up the idea because I agree, it is HOT. AS. HELL. 😂 I replied and told them I’d tag them once it was finished. Hope you like! Enjoy! 💜

Age Recommendation: 18+

Warnings: SMUT! Oral (f. receiving) as in face-sitting, smutty sex, Yoongi being a whole-ass Renaissance snacc, paint

Word Count: 1,546

Summary: You and Yoongi live in a modest home somewhere in Renaissance Italy, with him trying to earn a living through art. Unfortunately, you keep distracting him even though that’s nowhere near your intentions.

I sat in the corner of the room, subtly risking a glance at him from the pages of my book. Yoongi was currently swirling his paint brush in the tin filled with the darker blue, lost in thought. “Are you quite alright?” I asked, prompting him to flick his gaze my way.

“I am, thank you,” he murmured, fingers tugging at his beret. I let him carry on, admiring the way his trousers hugged his legs as he moved between the canvas and paint. When he shoved his tunic sleeves up his arms, showing off the creamy skin of those hands I loved pressing my lips to, I swallowed hard.

“I can feel you staring,” his deep bass grumbled.

I whipped my gaze back to my book. “Sorry.”

I listened to the scratching sound of the brush spreading color over the canvas, reveling in the way Yoongi inhaled as he smeared blue onto white, and the way he exhaled as he pulled the brush away. Risking another peek at him, I watched as he straightened, dipping the brush in the paint once more, before bending down the work on the bottom half of what would be his latest masterpiece. Yoongi repeated this action multiple times, silently working as I looked on. His hands were what my eyes were drawn to most, however, his veins popping as his grip on the brush tightened and loosened. I had to press my fingers to my mouth to stop from gasping at the sight.

Normally, he didn’t let me watch him work. Yoongi preferred for me to see the finished product, but as we’d had such little time together since his art started becoming popular, he relented and let me sit in on this painting’s creation. The only other time I’ve been allowed in the same room with him while he’s working is when I’m the one sitting for the portrait, and even then, I never got to see his process until now.

Yoongi finally sighed and set the brush down, his pale arms and smock now splattered with small droplets of blue paint. “You haven’t turned a page for nearly an hour,” he mused, looking at me with hooded eyes.

I opened my mouth to apologize once more, but he crossed the room and smothered my words with his soft mouth. “Never mind,” he murmured against my lips. “I was distracted, anyway. Your mere presence is a hindrance.”

“I can leave,” I muttered, attempting to turn away.

“No,” he growled, the sound low in his throat. “I want you to stay. Need you to stay.”

My eyes grew wide as he pulled me upright, his dark eyes boring into mine as he slid his hands around my waist. “Don’t be scared, my love.”

I shook my head. “I’m not scared,” I said breathlessly. Truthfully, I wasn’t. I was entranced… had been for the entire time I watched him work.

Yoongi reached around me and began loosening the ties of my dress, pressing his lips to the skin of my neck as he worked the strings loose. I sighed into his touch, trembling as he peeled the layer from my body, letting the fabric pool around my feet. He groaned at the sight of me just in my linen kirtle and corset. “Turn,” he ordered, and I spun. His nimble fingers worked at the knots keeping my corset together, skillfully undoing them the way he’d done so many times before. Yet I still shivered every time I felt his fingers touch my bare skin, trailing over my neck and shoulder as his other hand loosened the corset strings to the point where he was able to lift the piece of clothing over my head and toss it in the corner.

I spun around, becoming painfully aware of the fact that he was still fully dressed. I tugged at the hem of his tunic and he smirked as he pulled it off. “Impatient tonight, are we?”

Biting my lip in response, I fumbled with the ties at his trousers and yanked them down to his ankles, kissing down his torso as I did so. Yoongi groaned loudly as my tongue flicked out, tasting the skin of his creamy pale thighs. I lingered there, pressing the flat of my tongue against his skin, licking my way upwards. “Enough,” he grunted.

Smirking, I refused to listen, doing the same to his other thigh. He growled and grasped my hands, yanking me upright. “I said enough teasing.” I shivered, his husky voice going straight to my already dampening core. Yoongi reached down and grasped the hem of my kirtle, pulling it over my head in one swift move, making me gasp as the cool air hit my naked form. My nipples instantly hardened, and Yoongi sat back, devouring me with his eyes.

“You know, no matter how much I paint, you are still the most beautiful work of art I’ve ever seen.”

I felt a blush creep its way up my cheeks, and reached up to cover my face with my hands. Yoongi grabbed my wrists, pulling me so close I could feel his breath over my face. “None of that,” he murmured.

Yoongi led me to the bed in the corner and lay me down, nudging my thighs apart with a knee before he lay between my legs, his hard, throbbing length pressing against my folds. He rocked back and forth, the tip rubbing deliciously against my clit, and I cried out from the intense pleasure that shot through me.

He silenced me with a deep, passionate kiss, shoving his tongue into my cavern. I wrapped my lips around the muscle, sucking slightly, knowing it would drive him crazy. He let out an appreciative grunt and thrust his hips into mine, forcing a gasp from me.

He lifted his hips, the sudden loss of pressure making me whine, but he pressed a finger against my lips, shushing me. “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of you,” Yoongi said, deftly flipping us over so I straddled him. He grasped my thighs and guided me to the point where my core sat right above his perfect, pink mouth. Lifting his head, he licked a strip from the bottom of my folds to my clit, eliciting a loud moan from me. I began panting as he continued his handiwork, skillfully tonguing at me from every delicious angle, finally shoving the muscle as deep as he could go, making me cry out. He went between that and sucking fervently at my clit, and I felt my thighs begin to tremble as he worked me to my breaking point. “Yoongi,” I gasped. “I’m gonna… I mean, I’m going to-”

He groaned at my words, the vibration going straight into my core and pushing me over the edge. I cried out, my moans whiny and loud, as I released onto his tongue, panting his name as I came down from my high. “Yoongi… Yoongi…”

Only letting me have a second to breath, Yoongi speedily flipped us over once more, lying between my legs and pressing his hard, thick length into me before I had time to figure out what was happening. I felt my muscles stretching to accommodate him, relishing in the way my walls clenched around him and made him squinch his eyes shut as he bottomed out. “Ready?” he asked, letting his facial features relax into a smile.

I nodded. Yoongi wasted no more time, thrusting in and out of me at an insanely fast pace, using one hand to hold my hips still and the other to tightly grip the round flesh of my ass. I knew there’d be bruises in the shape of his fingers tomorrow, but at this moment, I didn’t care if I wouldn’t be able to walk. All I knew is I wanted him, I wanted him from the second he picked up his brush, and finally our bodies were melding together as one.

“Harder,” I hissed, scraping my nails down his back.

He obliged, speeding up to a pounding pace. I could hardly breath or feel anything but him inside me, thrusting in and out, the sudden, intense pressure of him inside me coupled with that same pressure abruptly releasing giving me nothing but raw, acute pleasure. I felt the muscles around my core and the bottom of my spine tightening, preparing for a second release. Yoongi’s grunts were coming out loud and frequent, letting me know he too was close. “C’mon sweetheart, let me feel you,” he moaned, and that was all it took to send me over the edge once more, my muscles completely contracting around him as they shook, clenching and unclenching.

He kept going, pushing me through my high, sweat making the tips of his soft, dark hair damp. Finally, Yoongi let out a low, deep grunt and pushed deep into me. I could feel him twitching, releasing everything he had deep inside me. He collapsed on top of me, both of us trying hard to catch our breath as we came down.

After a moment, he pulled out of me and rolled over onto his side. Yoongi smirked as he panted, his face still shiny with perspiration. “Maybe I should let you watch me paint more often.”

#bts#btssmut#btsimagine#btsimaginesmut#btssmuts#btsimagines#btsoneshot#btsoneshotsmut#painteryoongi#minyoongi#suga#btssuga#btsyoongi#btsminyoongi#paint#smutwithpaint#smuttyart#idiedwhilewritingthisokay#thisnearlykilledme#renaissanceyoongi#renaissancesuga#yoongixreader#yoongixyn#sugaxreader#sugaxyn

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Torrington: A Portrait of the Stoker as a Young Man

(Previous posts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8)

Different forms of art have depicted Torrington in different ways. In my last post I discussed how in music Torrington seems to be depicted as either some sort of restless spirit or reanimated man-out-of-time, with a focus on his death and the eerie undead appearance of his mummified body. There’s not much of a focus on what he was like when he was alive, with the inspiration for these works coming from the image of his dead body. Sadly, we don’t have any pictures of what he looked like when he was alive, but that doesn’t mean people haven’t tried to imagine it. In fact, Torrington’s depiction in visual artworks often focus more on what he was like when he was alive, with various attempts at reconstructing what he may have looked like before he died and was buried on Beechey.

One of the first attempts at recreating what he may have looked like comes from the Nova documentary “Buried in Ice.” At the very end of the documentary, there are artistic reconstructions of Torrington, Hartnell, and Braine. I’m not entirely sure who the artist was, but the credits list an illustrator, Wayne Schneider, and he may have been the one to draw these. I can’t find the illustrations outside of the documentary, so please forgive the bad quality of the screenshot I had to use below.

Here we have a John Torrington who looks aged before his time. He was only twenty when he died, but judging by the state of his lungs, he probably had a hard life, so he may have looked much older than his years. This is a very serious-looking Torrington, as if he were standing for a portrait or daguerreotype for several minutes and had to stay completely still.

This drawing also gives him almost shoulder-length hair. Owen Beattie was a technical consultant on the documentary, so he probably had a say in what the recreations of the Beechey Boys may have looked like. This makes me think that the hair length shown here is most likely how long his hair actually was. Yes, I know, I’m going on about his hair again, but due to the confusion over what his hair looked like, it tends to vary across artistic depictions, as we shall see.

Another thing of note in this recreation is the noticeable lines around his mouth. In the pictures of Torrington’s mummified body, there are prominent lines around his mouth, but how much of that was due to postmortem distortions and how much would have shown on his face in life is hard to know. The artwork above is not an official forensic facial reconstruction, and even official reconstructions are highly subjective, so this is just one possible interpretation.

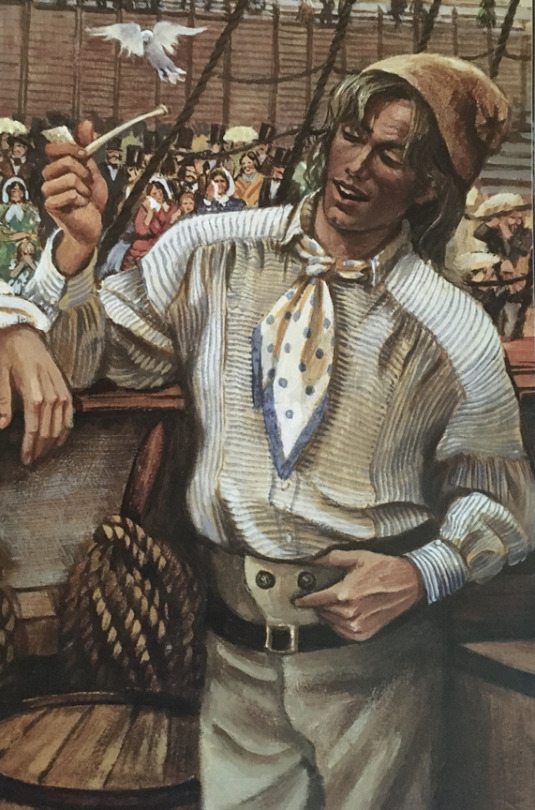

There’s another artistic interpretation of Torrington from around the same time. Remember the children’s book Buried in Ice? Well, what’s a kid’s book without some illustrations?

Now that’s the face of a man who got sick of backbreaking, lung-destroying labor in Manchester and said, “Screw it, I’m going to the Arctic.” The hair here is similar to that depicted in the documentary illustration, but the lines around his mouth are softened. The illustrations for this book were done by Janet Wilson, and she brought a liveliness to Torrington’s face that the somber drawing from the documentary greatly lacked. He still has a slightly careworn face, but he looks closer to his actual age. Janet Wilson also did wonderful detailing on the shirt that he was buried in, which he is wearing in her drawing. The kerchief tied around his head in death is here tied around his neck—and I love the inclusion of the blue border around the kerchief, which is not really noticeable in the photos from his exhumation but is noted in the reports on his burial clothes.

I’m fond of this picture because it gives Torrington some personality beyond that of a sad, tragic victim. It makes him seem like a real person who lived, with a bit of a sly and carefree attitude. He also gives off a kind of back alley salesman vibe, like he knows a guy who knows a guy who could sell you a kidney. But I especially like it because he’s smiling as he’s speaking, and after seeing picture after picture of Torrington’s frozen death grimace, I would love to know what he looked like when he smiled.

There’s another artistic reconstruction which I found on YouTube. It’s by artist M.A. Ludwig, who has a YouTube channel (under the name JudeMaris) dedicated to facial reconstructions of various historical figures, including all three of the Beechey Boys. Here’s Ludwig’s interpretation of what Torrington may have looked like:

He looks much younger here than in either of the two previous interpretations. This John Torrington looks like a young man ready for adventure, with hopes and dreams of a long future. He has slightly shorter hair in this interpretation, but also, he’s blond. I’ve noticed confusion online about the color as well as length of Torrington’s hair, with a lot of people these days thinking he’s blond. I think that may have something to do with the wood shavings he’s resting on in photos, which as I discussed in a previous post, some people have confused for his hair. I’ve also encountered a few versions of the usual photos of him where the lighting looks different, resulting in the few visible wisps of his hair looking much lighter than official reports have described them. Interestingly, the blond hair makes him look younger and gives him an innocent and almost naïve appearance, completely different from the sly, I’ve-got-a-bridge-to-sell-you Torrington from the children’s book.

Now I’m going to move on to an artist who is well known to Franklinites. Kristina Gehrmann (@iceboundterror) is a German illustrator and graphic artist who specializes in works with a historical or fantasy setting. She has drawn many pictures inspired by the Franklin Expedition, and I have bought several of them from her shop on Etsy, including three different versions of the ships Terror and Erebus sailing in the Arctic or caught in the ice. Currently, those three pictures are on my wall next to a large painting I inherited from my grandparents of two non-Franklin-related ships that I pretend are Terror and Erebus anyway (I call this wall The Boat Place). Gehrmann also wrote and illustrated a graphic novel in German about the Franklin Expedition, Im Eisland, published in three parts and available through Amazon. But if, like me, you don’t speak German, Gerhmann has made an English translation, titled Icebound, available for free here.

Gehrmann has actually drawn two slightly different versions of Torrington, one of which is more like the artistic reconstructions shown above and the other is of a fictionalized Torrington in the graphic novel Im Eisland. I love both of her interpretations, but they are of two different styles. Let’s start with the graphic novel version.

Im Eisland uses a manga-like style, so this version of Torrington is based in that. It gives him a wide-eyed, youthful—and joyful—appearance (when he isn’t dying of consumption, of course). This is the happiest and liveliest Torrington I’ve seen. The manga art style results in some simplified features and a rather modern hairstyle, but there’s nothing wrong with using some artistic license to better convey the personality of a character.

Gerhmann’s other illustration of Torrington is possibly my favorite, even if it might not be the most accurate:

This is a lovely illustration, and it really plays up Torrington’s youth, making him look almost angelic. I’m going to be completely honest—he is very pretty. This version of Torrington is an incredibly handsome young lad, and if Torrington really looked like this, then I think he probably would have been very popular in life. I could go on, but I probably shouldn’t.

I also love the amazing detail on the shirt. You may have noticed some slight variations in these recreations when it comes to his shirt, and I think that’s due to the fact that his shirt looks downright complicated in the few pictures we have of it. There are horizontal stripes and vertical stripes. There’s a high collar and buttons and all these folds that it can be hard to see exactly what it looks like, and unfortunately there were no textile experts present during the exhumation, so there was no one to lay out the shirt and take a closer look at it before redressing and burying him. But every time someone gives their best attempt at figuring out the puzzle that is his shirt, I’m happy, and this one looks very close to how it may have actually looked. My one issue with this picture is that his hair is short and blond, which doesn’t fit the description provided in the autopsy report. But the facial features look true, so I tend to overlook that little nitpick.

This version of Torrington, by the way, is probably the most well-known interpretation. In fact, when you search for John Torrington on Google, this picture crops up:

I have even seen online articles about Torrington that use this picture as a reconstruction example. This is in no way an official reconstruction of him, but it is by far the most popular. (And yes, I bought a copy of this picture, too.)

While reconstructions of what Torrington may have looked like when alive are common among artists depicting him, there is some artwork that uses images of his mummified body as inspiration instead. Irish artist Vincent Sheridan has a gorgeous collection of work inspired by the Franklin Expedition. Several of these feature the mummy of John Torrington, including an etching aptly named “John Torrington.”

Torrington appears as a ghostly apparition in many of these prints, alongside the repeated imagery of a skull, two very physical signs of the human cost of the expedition. While most of the bodies of the men lost have yet to be found, their bones scattered or buried across King William Island, Torrington’s body is a stark reminder that this tragedy did happen, and that these men did die, not just vanish off the face of the earth. I’ve described Torrington as the poster boy for the expedition before, and here his death seems to represent the death of everyone who sailed with Franklin, his face a haunting piece of evidence for the fate that met them all.

Now, I’m not entirely sure how best to transition between that solemn reminder of death and this last piece of Torrington-inspired artwork that I would like to mention, so I’m just going to dive in. This next artwork also uses the image of Torrington’s mummy as inspiration, but in a completely different manner from Sheridan’s work. I refer, of course, to the John Torrington plushie.

This adorable little mummy plushie was created by craft artist Nancy Soares, aka sinnabunnycrafts on Etsy (@sinnaminie). Whether you think a plushie of a mummified body is in good taste or not, you have to agree that this little guy is freakin’ cute. I might be slightly biased, though, because he was originally crafted for a custom request from my sister as a birthday present for me. But now anyone can buy him or his Beechey buddies. This little guy even made a special appearance during John Geiger’s presentation at the Mystic Seaport Museum’s symposium, Franklin Lost and Found.

I think the fact that there’s a plushie of John Torrington is amazing. People used to take pictures of the recently deceased and use their dead loved one’s hair in jewelry to remember them, so this isn’t that different. To me, at least, it’s a memento to honor him, reminding me that Torrington was more than just a boy who died but a boy who once lived as well.

It is also super adorable.

Next: Torrington as depicted in literature. Spoiler alert! He dies. A lot.

<<Back | Next >>

Torrington Series Masterlist

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Visiting Friends, Lessons Learned, Part 1

“Roving Amongst the Redwater”

Notes by Dr. Marta Carpools

At first glance the entrance to the Redwater Complex, or the Hold as the inhabitants call it, is particularly unassuming. A small outcrop of reddish brown stone that, if you happen to come close for some reason, opens into half again the width of a medium sized caravan with two people walking on either side, a bus could fit with some room to spare, though if driven very carefully. The descent is almost immediate, and it is only after you have entered the otherwise spacious tunnel that you notice it is not a natural occurrence, but one very cleverly built, with smaller tunnels splitting off like blood vessels up towards, you realize, the nearby farmland that is, apparently, not as abandoned as it seemed while passing. Of course, if you’ve made it this far, you know the land is very much inhabited.

Two kinds of people enter this territory nowadays: Ones who know the Redwater are here, and those who do not. Of the former, it is either friends of one of the Clan members, like ourselves (we being myself and my mentor, Dr. Metro), or those who heard the call of safety under the surface of the world. Of the more numerous latter it is, at best, on accident, at worst a band of ner-do-wells

Regardless of which you are, you will not be alone in this area for long, I have discovered. It was not half an hour after crossing the south-eastern border on the map (provided by friends within the Black Diamond Trading Company) that two figures trotted up to us from the west, in the direction of the lake north of what was once Bravo.

They moved with a predator’s grace, and I was reminded strongly of the gorehounds I’d seen at the Iron Harbor. I will blame their covered forms for my immediate instinct to depersonify them. I had once thought Wandering Eye’s layers of scarves and leather were impressive, but I realize now that is the look of a lascarian who has spent much time above the surface, and has, however little, adapted to the light. These figures instead wore the full regalia of people accustomed to darkness below ground and moonless nights, layers upon layers of cloth and metal covered leather, hung with hardened leather leaves and small metal trinkets I knew enough to recognize as Memories and Clan marks. It made them seem less living being and more a moving statue. It was impossible to tell build or shape looking at them, and if it weren’t for one being a head and shoulders shorter than the other I’d be inclined to believe they were twins, or some cloning experiment of the Darwins.

I have been interested in these people since learning about them from the aforementioned part-time resident of Bravo, Wandering Eye, or as I have learned since visiting him in the Sunless Garden, ‘Gangarani’eygr’. I will continue calling him Wandering Eye so as to avoid any accidental insult. As such, I hope to make as accurate a description as possible of what I witness within their territory.

With that in mind the two figures cut an impressive portrait, the afternoon sun throwing their shadows long over the sparse grass and rocky sand. They each carried a shield and spear, though the taller had a sword strung on his back, the shorter several knives strapped to her (I would learn later it was a woman) clothing.

The shields were small, by Bravo standards where one could easily be used as a door. Still, the ovals of wood and scrap metal was tall enough to cover shoulder to knee, nearly as tall as myself, though I am by my own admission, not the most gifted in height. Each was carved and painted in whorls and glyphs, their true meaning a mystery to me even now, though I might assume they were ownership marks, or religious in origin, if I knew less of their culture. I am told that while the Runner sect, as I have learned they belonged to, does not have as extensive a glyph system as the Keepers to which I have become marginally better acquainted, they still guard it closely and have many symbols they consider important.

The spears were 3-4feet of a dark hardwood, though I could not tell you the species (perhaps cedar? Oak? I am less well versed in flora than anatomy, unfortunately.). They seemed burnt black, yet glistened like volcanic glass. I am unsure what process is used to create this effect, but it is striking nonetheless. The tips were worked metal, a long blade with a flat front edge, and a concave back, still sharp. I have done my best to recreate the design below:

We stopped as they approached, and Metro made sure his weapons were secure on his belt before holding his own shield to the side and raising his other hand to show he meant no harm. I did the same, for all I lacked any weapons to secure. They showed no response while they closed. I felt the distinct impression they wouldn’t have reacted had we leveled any manner of defense against them. We were strangers here, they were the ones to be afraid of, though there were only two of them. It was then I remembered some old wisdom from back home:

‘For every lascarian above ground, you can be certain a half dozen lurk somewhere nearby, hidden, waiting for the signal to join their friend.’

I will admit I felt a shiver of trepidation at that thought, the kind I was learning well out here in the world beyond the Killscout compound. However hospitable Wandering Eye had seemed in town, I remembered well first meeting him, and the eyes of a hunter he hid behind his glasses. I felt the same look from these two, though perhaps it was my imagination at the time.

Within Bravo, where they were outnumbered by almost every other strain of post-humanity and generally well behaved, where stories of a pack overrunning a caravan and leaving only chewed bones behind were more joke than serious worry, I think it was easy to forget lascarians are some of the most dangerous creatures living in our shared world.

That fact was very clear to me as the two split and circled us, one to the back, and the other to the front. The shorter spoke in heavily accented speech and after a terse moment we were being escorted towards the north.

Our journey through the entrance described above was largely un-notable, beyond those things already noted. We crossed paths with a few other Redwater at the entrance, and I was surprised to see a slow and small, but steady stream of other strains moving about the side tunnels with lascarian guides to destinations unknown.

Following their lead, the taller of our escorts split down one of the tunnels while the shorter continued with us, stopping briefly at a small chamber to remove their outer layers and head-gear. It was here I discovered our escort was a lascarian woman named Whispering Storm, who was by happy coincidence an old friend of Wandering Eye, and had heard our names from him. Her partner, the silent Blood-of-Oaks, had returned to their patrol group while she sorted out getting us access to the Hold.

While I am not an expert on lascarian physiology to know whether the Redwater are typical of their strain, I admit surprise at the variance I was seeing among them.

Wandering Eye, for example, is a towering man with broad shoulders and midsection, bearing the long arms I have generally associated with such individuals of his strain. His bearded features are rounded, though they bear some of the raptor like qualities of the greater lascarian community, especially in the eyes and brow. His teeth of course are quite standard for the species. On the rare occasion I have seen his head uncovered I’ve noted his close cropped hair, and the slight downturned point of his ears, a trait I hadn’t associated with other lascarians and thought previously to be perhaps an individual mutation of some sort.

By contrast, Whispering Storm, though she too bore the eyes and ears of our mutual friend, was a more slender and well-muscled figure, of decidedly average height. Her hair was dark, a blue tinged black I’m not positive was natural, and long, though the sides of her head were shaved and its length was kept in thin, beaded braids gathered behind her head. I noticed a few Memory trinkets were woven in among them.

Both were of course paler than the fairest strain born above ground, almost corpselike, in fact. Whispering Storm, however, though she also bore the nearly familiar facial marks of a Redwater Clan member (three wavy lines over the right eye, a half circle and line over the left), was a study in culture all on her own; her skin, as she changed into what was apparently more common garb for meandering through the Hold, was seemingly covered in scarring, some of which appeared to be done intentionally, even artistically, and the ink of many tattoos, giving her the appearance of a sketchbook sewn into a living creature.

I’m unsure exactly how much of her skin was modified in such a way, but most of what I saw, and I saw much of it, seemed to be. The clothing she changed into was, I admit, more comfortable looking than my own (though I’ve never felt particularly burdened by them), however I felt some small desire to wrap a blanket around her lest she catch a cold. I suppose I should acknowledge she seemed wholly unaffected by the chill I’d begun feeling in the air as we moved further under the earth.

Metro and I exchanged glances, I noticed a slight blush on his cheeks and he averted his eyes from mine while she placed her knives around the form fitting, dark brown leather harness that made up a significant percentage of her new shirt, the rest consisting of a very soft looking linen that left her shoulders, back, and midriff bare. Her legwear had also been exchanged from the unbleached, durable fabric she’d worn above ground to a deep green pair of pants that looked to be of similar material as her upper garment, tucked down into the boots that seemed the one piece of clothing she had not replaced.

During this time I should not fail to mention she had attempted small talk with us, and I discovered she was quite friendly, especially compared to her partner. She kept up a dialogue with us, somewhat less effective than intended due to her unfamiliarity with the language, and continued asking questions and answering a few of our own even as we departed and continued on our way.

I cannot verify the distance from our changing room to the great Gate, but I can say it was many steps, and at least two surprisingly sharp turns. The side tunnels gradually became smaller, and fewer in number, and the main had ceased to appear like a natural opening of rock, instead squaring off at the corners, creating a smooth floor and ceiling. The torches that had lit the early stages of the journey became fewer and far between, casting our path in shadows. It was almost surprise when I realized the sounds of echoed footsteps had grown beyond our own, and I saw my first glimpse of the Gate.

It was a massive thing, a wall of stone and metal, reach across the fill width of the tunnel, and almost to the ceiling, several times my height at this point. I saw figures moving at the top, and in the center was a thick metal door, currently open, and seemingly built to slide sideways rather than inwards or outwards. Through it, and beyond, opened a cavern that stretched to the left into darkness, though I could make out the shapes of a few caravans, mostly pick-me-up trucks and iron horses, though at least one larger ride was present.

Passing through the Gate was a simple process, there being only a small crowd in the area, and most were waved through without issue. Whispering Storm called out to one of the guards in their native tongue, and he nodded, replying with an air of routine, and a few minutes later we found ourselves moving through the entry cavern, and on a stone road, moving deeper into the cavern, where small buildings seemed to grow out of the rock walls. Almost immediately two things became apparent:

One, this place was far larger than the current population could fill. There was no shortage of individuals, most lascarian, though I saw plenty other faces blended into the populous. Hundreds currently wander the underground center of Redwater culture by my estimate, and yet there seemed to be room for hundreds, several hundreds, more. For every building I saw signs of life (a candle in the window, polished tools on a workbench, or just the lack of feeling empty) there were three or more that I was surprised didn’t have boarded windows and an inch of dust on the steps.

Secondly, the city exuded a sense of age that made no sense for a home built within the last year, as I’d been told it had been. It wasn’t just the scope of the Hold, though it was in part the feeling a year could not have been long enough to build such a place. The subtle differences in certain blocks, how buildings grew together, and the shape of them, all felt as though I was walking through an oldcestor history book.

I stamped down on the unease I felt, as we roamed the streets behind Whispering Storm. I told myself I had no idea what determined lascarians in large numbers could accomplish. Wandering Eye had said once that the Holdlings outnumbered the other sects combined twice over, and their very purpose was to build and maintain their home. I still could not shake the feeling of age the place held, though it lessened somewhat as I began to see signs of scaffolding and incomplete buildings the more turns we took.

Perhaps it is only that they build their home out of the bones of the earth that causes the sensation.

My introspection was cut short as we rounded another street, and came to a junction of buildings that moved into a new part of the Hold. The ceiling was lower here, coming almost to the roofs of the buildings, where it did not replace them entirely. The streets began twisting on themselves, creating alleys and alcoves of dwellings. In the distance I was able to make out the shadows of three larger structures, the size of warehouses, just a bit taller than the rest of the buildings. They seemed identical from the vague look I could get, and faced different directions. The effect walking through this new area of the Hold left me feeling somewhat claustrophobic, I confess.

At asking what this place was, Whispering Storm answered we had entered “Ward-way-air-stad”, and at the looks on our faces I suppose, added “Keeper District” a second later.

I commented about the feel of the place, and she nodded, with a slight smile, replying that the Keepers like tunnels. I suppose that makes sense.

Lascarians like tunnels, everyone knows that.

Three turns and a small hill (there are hills underground, I have learned) passed us, and we entered a small lane. On our left was a slightly larger building that created the last turn, on our journey. It seemed empty but had the feel of a temporary state, as though it was normally inhabited. To our right small homes broke up the wall of the cavern.

Small lamps were hung from the places the buildings met in this part of town, and unlike the torches and candles of the earlier parts of the Hold, the light pulsed a pale blue color. I paused to examine one and discovered they weren’t lamps at all, but small, glass covered, stone planters full of mushrooms and moss from which the light came from. Small insects darted about the light-gardens, themselves bursting in tiny sparks of gold and green intermittently, sometimes taking flight towards one of the other holders.

At the end of the alley we found a surprisingly idyllic scene: a dwelling facing the street, built into the back wall of the cavern as it bent left. Between the building and the one closest to its right was a small elevated slab, from which a simple fountain emerged from the cavern rock. Over it was a wooden framework, hanging with more moss and mushrooms as grew in the lamps. Underneath it all, at a small table sat Wandering Eye, writing in a leather bound book.

He stood as we approached, and smiled. I almost didn’t recognize him uncovered by scarves or hat, I’m embarrassed to confess. He, too, was dressed simply and comfortably. In light brown trousers, and only a draping green vest, which fell to his knees but left his arms bare. It was the first time I’d seen him uncovered so, and I was surprised at the number of scars that mottled his skin, though unlike Whispering Storm, none of these seemed to be done intentionally. Most prominent was the burn on the inside of his left forearm, a wound I recognized from two weeks past, when we were in Bravo for the last time together.

Before Metro or myself could reach him, Whispering storm moved forward, and pulled his head down to hers, touching their foreheads together and whispering something that sounded like “essayo”, before promptly hitting his shoulder hard with the back of her hand and unleashing a stream of words in their language while gesturing at the aforementioned arm.

Wandering Eye took it in stride, and waved her off with a few quiet words and a gestured at the two of us. She mad a noise somewhere between a sigh and a growl, a sound I realized in that moment I’d heard often from our mutual friend, and marched into his home while he stepped up and pulled us both into a hug, motioning to the seats around the table he’d been sitting at, to join him.

We’d only just sat and begun to exchange pleasantries when Whispering Storm reappeared, throwing a bandage roll at her Clan-mate, and glaring at him as she took a seat at his side. He picked it up from where it had bounced off of him and made a quick hand gesture that she gave a satisfied nod at.

Marta Marta

-

“Marta?” Wandering Eye asked for the third time, with no little amount of amusement in his voice.

The small rover woman jerked her head up from where she’d been scribbling in her notebook, then looked back long enough to scratch out a line before closing it with a smile and turning her attention to the rest of the handful of individuals in the room.

“Yes! Sorry! I wanted to get everything written down before I forgot,” She blurted out.

He waved the apology aside, with a freshly wrapped arm. “Do you want tea?”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about George Washington’s ‘wooden’ teeth

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/heres-the-uncomfortable-truth-about-george-washingtons-wooden-teeth/

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about George Washington’s ‘wooden’ teeth

George Washington faced many challenges regarding his teeth. (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC/)

We have all heard the tales about George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, throwing a silver dollar across the Potomac Rive, and, of course, wearing wooden teeth.

They are all just myths, but one thing is certain: The father of our country suffered horribly with dental pain. Today, the dental profession has many ways to relieve dental pain and to replace missing teeth so that they look and feel like natural ones. Unfortunately for Washington, 18th-century dentistry could not provide the much sought-after relief from dental suffering available today.

I am a professor of dentistry who has studied the history of Washington’s teeth and have found it very interesting separating fact from fiction regarding Washington’s oral health.

The myth of the wooden teeth

George Washington by Charles Willson Peale. The swollen cheek and a slightly visible scar could have been due to an abscessed tooth in the young soldier. (Charles Willson Peale/)

While it is a myth that Washington’s false teeth were made out of wood, his pain and embarrassment from his dental woes were all too real. What might have led people to believe that Washington’s teeth were made from wood was the brownish stain on his denture teeth, which was most likely the result of tobacco use or stain-inducing wine.

Washington is best remembered for his heroics against the British in the American Revolution, but he started his military career in the Virginia Militia fighting alongside the British during the French and Indian War. Washington’s dental problems likely started during that time. It was also about this time that he wrote to his brother that “I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me there is something charming in the sound.”

But Washington had more than bullets and war on his mind. Washington at that time also wrote in his diary that he had paid five shillings to a “Doctor Watson” for the extraction of a tooth. During the war, Washington purchased dozens of toothbrushes, tooth powders and pastes, and tinctures of myrrh. Unfortunately for Washington, his dedication to his dental health did not prevent the dental suffering he would endure throughout his life.

In an attempt to both flatter Washington and thank him for liberating Boston from the British in 1776, John Hancock commissioned the great portrait artist Charles Willson Peale to produce a painting of Washington. Peale created a masterpiece that shows a scar on Washington’s left cheek, which is said to have resulted from an abscessed tooth.

Washington’s cousin, Lund Washington, served as the temporary manager of the Mount Vernon estate during the American Revolution. While George Washington was in Newburgh, New York on Christmas Day, 1782, he penned a letter to Lund.

In this letter, George Washington asked Lund to look into a drawer of his desk at Mount Vernon where he had placed two small front teeth. We do not know who the original owners of these two teeth were, but it could have been one of several slaves’ teeth that Washington purchased over the years. At this time, Washington’s dentist was Dr. Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur, who had many wealthy patients and was known for his practice of paying individuals for their healthy teeth to be used in the construction of dentures for his wealthy patients. Selling teeth to dentists was an accepted way of making money at the time.

At the time of Washington’s death, 317 slaves lived at Mount Vernon. A simple notation in the Mount Vernon plantation ledger books for 1784 may reveal the source of some of Washington’s denture teeth. The notation simply reads: “By cash pd Negroes for 9 Teeth on Acct of Dr. Lemoin.” (Lemoin is the same person as Le Mayeur.) Historians also do not know for certain whether those teeth ended up in Washington’s dentures.

A man of few teeth, and words

Washington’s dental health even affected his two presidential inaugurations. Washington first took the oath of office of the president of the United States on April 30, 1789 on the second-floor balcony of Federal Hall. At this time, Washington had only one natural tooth remaining.

Dr. John Greenwood was a well-known dentist who practiced in New York City. Dr. Greenwood made a denture for Washington in 1789. The denture was made from carved hippopotamus ivory, human teeth and brass nails—no wooden teeth! Dr. Greenwood made a hole in the denture so the denture would slip snugly over the one remaining tooth—his lower left first premolar—and provide some retention. This tooth would eventually need to be extracted by Dr. Greenwood, who placed this tooth into a locket attached to a pocket watch and chain. Both the locket and the denture now reside in Manhattan’s New York Academy of Medicine.

Washington was very self-conscious about his dentures and considered them to be a sign of weakness, which could be seen as a threat to the credibility of the youthful nation. So, rather than delivering the first inaugural address to the assembled masses lining the streets in front of Federal Hall, Washington retired to the privacy of the Senate chamber, where he delivered his address to the members of Congress.

On March 4, 1793, Washington delivered his second inaugural address in the Senate chamber of Congress Hall in Philadelphia, and his dentures were causing him much pain and difficulty. His speech is still the shortest inaugural address in history, lasting only two minutes and consisting of only 135 words—shorter even than Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Bulging lips

In honor of #PresidentsDay, here’s an inside look at George Washington’s lower denture and last remaining tooth that are part of our Library’s collections, via @untappedcities: https://t.co/6fdObyid2T pic.twitter.com/1jswSTtzAF

— The New York Academy of Medicine (@NYAMNYC) February 18, 2019

Gilbert Stuart produced what would become the most well-recognized portrait of any American president to this day. Stuart, born in Rhode Island, lived in London and Dublin for 12 years, where he mastered the techniques which would produce over 1,100 portraits during his prolific career. Stuart returned to America with the intent of making his fortune by producing a portrait of the hero of the American Revolution, George Washington.

The only problem with Stuart’s ambitious plan was that he did not know Washington. However, a letter of introduction from Chief Justice John Jay led to Washington agreeing to sit for a session, in 1795, at Stuart’s Philadelphia studio. Washington’s face was sunken from the poor facial support provided by his ill-fitting dentures. Stuart placed cotton in Washington’s mouth, and the resulting portrait became known as the “Vaughan” portrait, as it was purchased by Samuel Vaughan, who was a London merchant and a close personal friend of Washington. Stuart went on to make 12 to 16 copies of the Vaughan painting, until Washington agreed to sit for another portrait.

In 1796, Washington sat for that other portrait, which became known as the “Athenaeum” portrait, a version of which appears today on the one-dollar bill. In this portrait, Stuart captured the bulge in Washington’s lips from his dentures, making his lips considerably swollen.

Myths and legends concerning all aspects of Washington’s life have become part of American lore, but even this iconic figure of American history could not escape the misery of poor dental health.

William Maloney is a Clinical Associate Professor of Dentistry, New York University. This article was originally featured on The Conversation.

Written By By William Maloney/The Conversation

0 notes

Text