#washington and oregon west of the cascades can come too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

have always been skeptical of state or regional-level secession movements because I generally feel that more borders do not solve anything but also if California put secession on the ballot right now I'd have a hard time not enthusiastically voting yes

#not to be a cringe west coast liberal about it because obviously california has massive problems and is not some kind of lefty paradise#but given today's events i think i'd take my chances#washington and oregon west of the cascades can come too

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

So bja and the others are right on them for the money in the stock and they're going after it hard and these guys are losing and they're losing Intel and information and by the boatload and it's soon going to be more and they will not be here it is going to Cascade and it is going to become very huge and they are going to get killed and ruined and we have discovered these people are asking for trouble same dumb things and things are sucking down and unfortunately shrunken down is unfortunately some of it looks real so people going after them and they're horrible horrible people just so dumb but here it is in a nutshell there's other things going on and it's war in the eastern hemisphere there is a big war today and it's going to get bigger tonight no it was huge

+a large number of pseudo empire fell in the eastern hemisphere so these people are motivated and they can see Trump and they need his stuff and he's kind of a huge dick too and he usually try to aim it at her son and it doesn't do anything and you can see it it doesn't anyways and got his ass kicked today. Huge number of people see them running in and out doing movies and Shane done things saying dumb things and sending out orders they actually make sense and they're going after them and they are going after them hard because of what they did overseas they LED some huge attacks on the pseudo empire huge okay they are massive in scale they are depleting them of tons of stuff now the tax for both huge and on tons of bunkers bases areas of interest most of it to 35% across the board and they were also huge losses on the part of the Macklemore lock huge and Trump comprise 70% of those losses it's probably a percentage of the population of Earth and out of the remaining percent of Earth off Island which was about 11.5% they go down to 10.5% and Trump's 70% of that 1% which means that his share of the 11.5% was I think we said 4.5 so it's almost 3.5 or 3.8%. see huge loss for him and he will experience it and it's global by the way these this number is in the eastern hemisphere and out of the 4.5% about 2.5% it's in the west and 2% of the East and of course he lost 0.7% which is 1.3% now in the east is severely weakened people see him this week and 2% and 1% are meaningful is numbers is coming up to that on the east and they will consider that to be 1%, that and that's the max and they will be brought down to it here shortly out of 2.5% they only lost a little but it's not the fight over here now they're going up there to Northern New England Canada and Northwest including Oregon in Washington State for a huge battle and the north part of South America and all the other bases are pretty much done and they're coming here that's the pseudo empire and they're fighting these ridiculous idiots. Oven space up in space that is the morlock lost half its fleet again to the pseudo empire they had about $300 billion total left and that is really Trump's fleet the rest of them have about 500 billion and that's the Mac morlock but the Trump's lost a huge number today fighting over Mars they sent once again probably three quarters of the force and it's out of that roughly $250 billion and they sent $125 billion so he lost a good portion of it was his about 87 billion bringing his total for us from $300 billion down to 213 billion ironically and the main Force combined a 500 billion okay that does not include Trump's but is reduced a little bit to around 480 billion it makes a difference and they are going to go to Mars now in force of $300 billion fleet they are preparing and that's both of them and they are trying to go to Venus with 100 billion this pseudo empire has about 600 billion ships that are operational 200 billion they're working on and they are going to intercept and lay them low out of the force of $487 Bill plus 213 billion out of those numbers Trump is going to be partying with 100 billion and bja and company and others $200 billion leaving Trump with 113 billion only that's not that many. This is going on right now and it's huge the numbers are pretty clear and straightforwards that their fleets are getting small they were getting small the other day but their attitude is such that people can't tell now we hate these people I hate these people I need this dog s*** out of my face they are disgusting losers and talk about people like they're nothing they can kill them without trying I am very tired of it and sick of them provoking us

We're sending out orders now to rent ourselves of a lot of these pukes and lowlights and assholes there's too many they have too much to say and they're wrong all the time I don't want them out they've done this too many times provoking us and really the little b****** they're they're nasty little insects little imps and our peevish very very peevish

I tell you what we're going to go after him now for what they're doing here right now it's extremely insulting and annoying as hell

Thor Freya

Olympus

0 notes

Text

. Here’s a. bit of a write up on corps life.

my big number one? I wanna go back lmao. I’ve been home for a few days and I’m already to go back out there.

Anyways. I spent two months camping and working in the pacific northwest and. honestly it was the most incredible experience of my life. I was on a five person crew (four members and a lead) and of that group there were only two people that hadn’t already done a session of conservation corps either at this corps or a different one. This was my first time doing a corps! I was like. deadass shitting a brick before I left. I was so nervous to fly across the country (I’d never even flown before!) and go do something I’d never done for two months. I’ve been camping. I’ve been hiking. I’d worked outside for the last nine months and had two seasons of outdoor work in park maintenance. but this was living out of tent for TWO months. I was super excited but I was. so fucking nervous too. And god to fly? Airports seemed scary and busy and I was scared I was gonna miss a flight or not be able to find where to go. So the weeks leading up to my trip I was so goddamn nervous. But I did it lmao.

And then. corps life. We spent the first day doing orientation where I met my crew!! and then left to head to our campsite where we’d do saw training the next three days. We left the parking lot of headquarters to Colter Wall’s “The Devil Wears a Suit and Tie” and headed to an area in the Willamette National Forest. The drive there was incredible. I’d flown into Oregon the night before and really hadn’t seen much because it was 9:30 when I landed and had only taken a short lyft ride to headquarters p early in the morning so. This was kind of my first time getting to see more than the freeway of Oregon. It was so beautiful. The big ass trees and the river and the mountains were just. incredible. And then that night two of my crewmates made entirely too much spaghetti which we had for two nights. We then had to use the leftover sauce for another meal. Fun fact! We only had spaghetti once more after that. In two months. Spaghetti is usually a staple on corps. Not on Red Crew. We were scared. Also the crewmember who doled out the pasta portions for that very first dinner of too much spaghetti was banned by our crew contract from doling out grain portions. After that, we went into saw training. Three straight days of saw training and evaluations on the last day. We were starting at seven I think? Like, meeting a five minute walk away in full ppe with saws ready to go at 7am. I think I wrote that I woke up at 4:45 the one morning but honestly that may have been the jet lag. Saw training was exhausting but it was so much fun too. There was a lot of information to take in and I’d at least run a chainsaw before. There were people that hadn’t run saws before at all. On the third day of saw training, we loaded up into our rig (by the way! 2021 ford f250. super duty cab. extended bed with a truck cap. gigantic. massive. imposing. it also had no labelling. it was not marked with anything corps related. it did not even have license plates. it was probably a little intimidating when we were bass boosting driving around in that thing. but whiplash inducing bass boosting because like. notorious big to mumford and sons back to back. can you believe that we never got pulled over in driving almost 5,000 miles). anyways. we did saw evals in a burned zone. I got my bar pinched. I know what I’d do differently now but I have a lot more saw time. But I passed! My whole crew passed and are now USDA National Sawyer Certification A Class Sawyers. Or Feller 3s depending on how you wanna say it. I’m super happy because I got my first professional certification at 19. Although my card says I got it after my birthday but I did my eval before I turned 20 so I’m gonna take it.

After saw training, we went up to a suburb of Portland to. sigh. move sticks for Karens. The area we were in SCREAMED homeowners association. in the name of “fuels reduction” they had us pick up sticks and hike them down to the road. The sticks were down because the trees were dying from this shitty little park. The first week was cold and rainy and we moved sticks. We cleared out an area close to the road the first day and then the rest of the week we had to swamp (move/clear) sticks up a hill onto this narrow trail. Everyone had blisters because no one was used to walking up and down a hill all day. Carrying wet and occasionally rotting sticks. We’d hike it up the hill to the trail and then load sticks into shitty wheelbarrows and then take those down this narrow path on a steep hill when it was fully loaded with sticks. By the end of the week we were walking a good quarter/half mile to the the road with heavy wheelbarrows. It was miserable. NO one wanted to complain because it was our first project but. eventually we all came to the conclusion that it was bullshit. It had nice views tho. Still my least favorite project. Even thought it was miserable I still like. had fun??

After that we went into Washington and planted trees. We actually did this for two weeks but with another site in between. This site uh. did not have bathrooms. Learned how to use a cathole. It hailed the first time I used a cathole. That was exceptionally miserable. But we planted trees! I wasn’t a huge fan of the site our first time there but I warmed up to it. We planted over 3,000 trees in our two weeks. One of our project partners stayed out with us, which mad respect. He was so sweet. We all joked that we were a little in love with him. He wound up hanging out with us during a few of our campfires. He told us about this trip he’d taken back in college to Peru. At this site we coined the phrase “meat plate” which would stay with us until the end of session. Meat plate is dinner that is just, assorted meats that need to be gotten out of the coolers. Also on this site a crewmember got his hand in stinging nettle while taking a shit. The first week was cold. It was rainy and shitty, mostly on the weekend. We did check out the ocean though!! I’d never been to see the ocean and we took the 101 north from near the Willamette to where we were and stopped actually at Fort Stevens State Park and that’s where I got to see the ocean for the first time. In march! It was sunny but actually super nice. We all waded in and one of my crewmates jumped in. It was march. IT was cold. This is the Pacific Ocean. Anyways he’s built different. The second time at the site was a week later, and it was super pretty. It was much better weather. We planted more trees.

Third week was further in Washington like an hour drive from Olympia. This was my first time seeing snow covered mountains that were massive in the distance. We cleaned up 195 trashbags of plastic plant protectors. Also kind of a shitty project but hey. Wasn’t hiking stuff up hills so. Our partner for this had people come talk to us for educational stuff which was okay, bad, and fantastic in order lol. The partner sent people from their org to be with the speakers (who weren’t part of the org) and we told the one lady what we’d been doing and she started LAUGHING and she was like “I’m sorry they gave you that project it’s because no one else wanted to do it” thanks. it was a shitty task but our partners were so nice that it made up for it. they even got a portapotty on site for us. no but they were all super nice. oh god they’d told us not to yell/slam doors/make loud noises because there was an owl in the barn on the property. we all were loud people and kind of forgot but it was okay we didn’t scare the bird. the bird scared us. one of my crewmates got up to go pee in the middle of the night and it swooped at him. this place was great for birds. We had a very angery killdeer beep at us!! we pulled out scotchbroom from the corner of the property and every time we walked near where it must have had its nest it would very angrily beep at us. It was so cute. We all loved it. My crewlead would always yell back at it. “What!! What do you want!!” I love that lil bird. Pulling out scotchbroom was a trip. To pull out scotchbroom you should in theory be ale to use a weedwrench to pry it out. Right? No. This was old growth scotch broom. This stuff was two inches in diameter as the smallest. It wouldn’t always fit in the weedwrenches. At one point it took me, my crewlead, and a crewmate to pull a scotchbroom with as much force/bodyweight as we could put on it. A couple times my crewlead put his entire bodyweight on to it and wound up falling into blackberry lmao. There was so much blackberry there too my god. It was so painful. We all kept joking about letting our crewlead just burn the area in a prescribed burn to get rid of the invasives. In the parking lot of a different preserve from the same partner org I found a red dinosaur who became one of our crew mascots.

After our second week back planting trees, we headed back down to Oregon to work on a fuels reduction project. We were all so excited for this one. We’d gotten certed for saws at the beginning of the session and had been told that we were gonna be a saw crew doing mostly fuels reduction which our lead had specifically asked to do because he had experience with it. But this was our first real saw project with fuels reduction. The weather this week was amazing. It didn’t rain at all, which on the West side of the Cascades in Oregon in April is pretty weird. It was nice for us but Oregon was and maybe still is in a drought. yikes! anyways. this is when we went on a hike to Blue Pool in the Wilamette National Forest. We camped at a little municipal park with another crew! It was weird being around another crew again because we’d spent so long just on our own that we all starting to lose it a little. But the other crew was super nice and we played frisbee in the dark with them the first night we were in the area. The project? was amazing. We worked on private project with a conglomerate of partners in doing fuels reduction. This conglomerate of partners did a whole bunch of other stuff but we only did fuels reduction. That was a week of working in a burn zone moving sticks. Moving sticks and swamping and making sure piles were neat to be able to be chipped. We learned about dispersing and how to remove ladder fuels and where to leave small logs on the ground for ground fuel. My crewlead showed us hazard trees and took a few out. I really loved this project. I loved the “grab stick go” part of it. It was so much fun. I also got to run a lot of saw which was nice. And this property bordered a parcel of BLM land which wound up being the spot we went to go pee at. If you’ve never been West of the Mississippi river, which I hadn’t(!) you’ve never had the opportunity to be on BLM land. There is no BLM land in the East. I wanted to go on all five of big public land holders in the US and that’s the one I don’t have access to here at home. We actually wound up taking a “nature appreciation walk” because we finished our work early around this little nugget of land and it was so cool. It was right on the McKenzie river and it was beautiful. I found our second crew pet/mascot there, a large palm sized egg shaped rock named “Egg.” We were so filthy there. Four 10s in a burn zone makes ya pretty stinky when you dont get to shower. Actually, we weren’t as stinky here because we just smelled like ash. I had ash everywhere. We went out to eat after the last day and my crewlead hadn’t washed his face in four days and was completely covered in ash.

Our last project took us 8 hours back into Washington. It was a long fucking drive. We stopped at Voodoo Doughnuts in Portland tho which was incredible. We rolled into our spot in Washington at 12:40. We slept with our sleeping pads and sleeping bags under a pavilion and were woken up by a ranger the next morning who thought we were homeless or illegally camping. This last project was also kinda bullshit. We were working with the Feds who kept telling us to slow down. We were at this project site for three weeks. The first week we cleared trails of downed trees and brushcut. The second and third weeks we helped General Maintenance take down trees and did so many runs to the dumpsite. We moved a lot of sticks and logs and my arms still look super scratched from moving branches. This spot was in the high desert of Eastern Washington and it was actually super pretty. I didn’t think I’d like the desert all that much but there was definitely a beauty to it. There wasn’t shit out there other than the dam. From there tho we were able to go to Leavenworth, this funky little Bavarian themed village up near the Cascades. We also went to Lake Wenatchee, which wasn’t as fun because we had to go move a fridge for the office staff. We spent about seven and a half hours on our last weekend doing this. I’m not salty. But it was super beautiful so. It’s okay. And we passed a prescribed burn on the way back to our site.

There’s still so much more I want to write and talk about. I have to say I’m overall. just so glad I did this. I had the absolute time of my life. I have never had so much fun. I learned so much. I learned how to really put out a fire with a pulaski from my crewlead. He taught us how to use the Incident Response Pocket Guide to cross reference and look at the probability of ignition. I learned how to use a chainsaw decently well. I did a lot of things that were far beyond my comfort zone. To fly literally halfway across the country, from Ohio to Oregon, for two months and to live in a tent and work on a conservation corps, it was super beyond my comfort zone. I did things with a saw that were beyond my comfort zone and I had to trust in my ability to saw and trust in my crewlead to let me do something he felt comfortable with me doing and thought was in my capability. And it was it was so fucking cool. I really bonded with everyone on y crew too. I made some good friends. And just like. The things I was able to see and do were amazing. And it was so nice to spend so much time outside. I didn’t spend more than an hour or two at most in a building in two months. I worked in 50s and rain wearing rainpants and chainsaw chaps and I worked in the 80s and sun in chainsaw chaps. I was able to lift a full 5 gal of water (40lbs) onto my shoulder and I’m still super proud of it. I watched a ton of movies in the rig with my crewlead and one of my crewmates. I got to use my crewlead’s chainsaw which was a lot cooler, sharper, and bigger than our corps saws. I cried about trees a lot. I celebrated my 20th birthday in a state park with people I didn’t really know too well who surprised me with homemade rice crispie treats and snacks from the Chevron we were regulars for that week at. I hiked some really pretty trails. I gave a lot of hugs and got a lot of hugs. I became not as terrible at hacky sack. I realized that There Are People In My Life Who See Good Things In Me and I Just Want To Keep Making Them Proud. I realized that I’m incredibly hard on myself. This whole thing furthered my belief of goddammit if I wanna do it by god I’ll do it. It’s been a dream of mine since I was 15 to go be on a conservation corps. I got interested in corps life at 15 because of Youth Conservation Corps posting in Wayne National Forest in southern ohio and since then had just. Always wanted to do it. And that literally changed my life - because of just hearing about corps I got super into parks and researched it and was like “oh i wanna be a park ranger” and I started working at the park doing maintenance and went to school briefly for parks and rec management and then dropped out to work more in parks. but then this year, after five years of wanting to do it, I finally did a conservation corps. Not a youth corps but an adult corps. Five years! The biggest dream I had was to work on a conservation corps. I just wanted to use a pulaski on a trail once. And I did at our last project site, even just removing invasives. But just. This experience was something I’d wanted to do for so long and to finally do it and have it be as amazing as I thought was just amazing. My crewlead saw me taking pictures in Washington along the Willapa bay and was just like “corps is a slippery slope. You either hate it or you get addicted to it.” Tragically I’m addicted to it. I can’t wait until next January and March to get back out there. It was such an amazing experience and I feel like I learned a lot of really good soft skills and really good hard skills. I can’t possibly explain to anyone the full extent of what this meant to me and all the fun I had but. This is a long post and I have to go replace my phone so this will be it for now. In the off chance anyone made it this far, thanks.

1 note

·

View note

Text

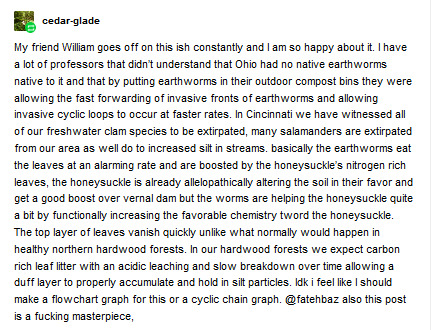

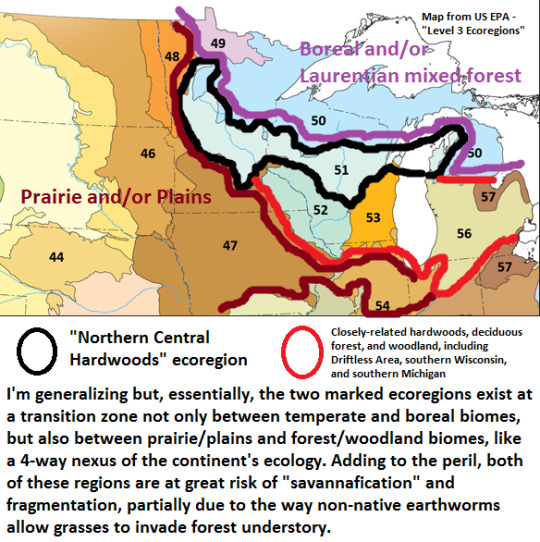

Some responses to Earthworm Discourse:

g u e s s a g a i n

Honestly, though, I still rescue earthworms from sidewalks and have since I was a child in our little informal, weird-girl, after-school bug-club, as I’m sure many of us did and still do. All life has value. (Still feeling confused about the ethical/ecological implications of rescuing non-native worms. When so many United States cities present as sanitized, sterilized, anonymous concrete-asphalt landscapes - covered in manicured non-native grass lawns - are the already-firmly-entrenched non-native earthworms causing much more damage in residential lawns if you save a few, so long as you avoid introducing them to intact ecological sites outside city limits? No pun intended, but that discourse is a whole other can of worms. Discussion for another time.) So I’ve seen some disparaging remarks made about the Moral Character of non-native earthworms, so obligatory statement: Earthworms of course are not villains or actively malevolent. Colonization; Indigenous dispossession; empire; profit-oriented thinking; industrial monoculture; large-scale geoengineering over years to reshape the entirety of the Turtle Island and Latin American landscapes as if they were “bountiful” European farms populated by “familiar and comforting” European species, etc. - earthworms are a physical manifestation of those issues.

-----

[Spokesman Review - 20 November 1999. Andrea Vogt, staff writer.]

Two of the largest and most iconic native earthworms on the continent are actually found west of the Rockies. Shout-out to [a commenter] for explicitly name-dropping the beautiful and alluring Palouse giant earthworm (Driloleirus americanus), a rare and elusive species, one of the earthworm species actually native west of the Rockies (from the Washington-Idaho border in the Inland Northwest). [More on the worm.] It lives in the Palouse Hills; in the nearby Nez Perce Prairie and Lower Clearwater canyon system; and in some sites in Washington’s East Cascades ecoregion. Much of the Palouse has been converted to agriculture, damaging the soil, and the worm was apparently missing for decades until recent encounters confirmed that it’s still alive. The Palouse giant earthworm and the endangered Oregon giant earthworm (Driloleirus macelfreshi) - from prairie-oak woodland of Willamette Valley - are both contenders for the title of “largest native earthworm in North America.”

-----

Excellent info:

-----

Nice to hear some info on boreal environments, thank you @theeclectickoalastudent - This is also how tiger salamanders (Ambystoma mavoritum) - native in North America east of the Great Basin - were artificially introduced to Mediterranean California: People were importing salamander larvae as fishing bait. (Pretty brutal to begin with, if you ask me.) And now the iconic, unique California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense) - endemic only to California and which was already endangered - is forced to directly compete to reclaim its own oak woodland and chaparral habitat from its introduced relative. And we can’t let United States “conservation” and land management agencies and institutions off the hook for the obscene and mind-boggling scale of damage they’ve historically done stocking non-native sport fish species in watersheds of the American West, followed by the stocking of non-native crustaceans to feed the fish. (Speaking of non-native species threatening salamanders, I was [just] hyperfixating the other day on how the Mazama newt - endemic only to Crater Lake, Oregon - may soon be driven extinct by the voracious introduced crayfish species Pacifastacus leniusculus.)

-----

Important disclaimer, by the way: I also wanted to clarify something, so I’m reposting some text I recently shared. Regarding the worm post, I wanted to say: [I know some people who have shared “unleash earthworms” posts clearly did so because: fun; irony; joke; etc. (And, yea, I really like imagining invertebrates/writhing creatures as emblems of resistance/anti-imperialism: “We’re worms, we’ve been stepped on for years, we persist! And our reward for submitting to the decay of the soil is to be engulfed in the loving embrace of one million mycorrhyzal fungal tendrils; by submerging ourselves into the soil we are really a s c e n d i n g.”) I was not vauge-posting about y’all. Like I said previously, I think peoples’ hearts are in the right place and I generally like people I meet here in anti-imperialist/ecology-oriented circles. I think that the originators of the most recent iterations of those posts were clearly being playful. My green tea-fueled ranting about Problematic Worm Etiquette is mostly due to: (1) sometimes I get Like That, (2) I’ll concoct any excuse to talk about Great Lakes regional ecology, and (3) I know some - not all - people were taking “release worms!” advice seriously, so figured it be nice to be explicit.]

On that note, regarding earthworm introduction as a means to improve your own access to food (via garden) or food (via using them as fishing bait): I did definitely see some people being serious about this, so it’s worth noting the irony of a well-meaning action which nevertheless deliberately introduces European species, erasing/degrading native ecology, and also resulting in the destruction of Indigenous foodsheds. Reshaping the Earth, remolding the continent, and promoting the physical/literal invasion of a European species in the hopes of making the land more “fruitful” and “bountiful”? In my US and/or Canada? Just as likely as you think.

Really important stuff right here:

(Sugar maple is one of the plant species most susceptible to death when non-native earthworms invade nearby soul. Thank you for sharing this, @aanzheni)

A map of native foodshed regions of Turtle Island/North America, based on a template originally made by ethnobiologist Gary Paul Nabhan, presenting hypothetical “food regions” and reflecting the vital local staple foods.

Sugar maple is important.

I talk too much, but @big-edies-sun-hat said it more tastefully:

--

@nonsensikelly - Thank you for the info. (And yea, earthworms are well-entrenched in temperate North America.)

-----

-----

I really am not a good person to ask. (Though I’d identify some blatantly obvious solutions - Indigenous autonomy and land management; the dismantling of industrial monoculture crop extraction and associated industry; etc.) I’m not a soil scientist, botanist, entomologist, or technical ecologist/biologist (more into environmental geography/history). However, I had your comment in mind when I wrote [this post] about loss of forest understory and savannafication in the Midwest, addressing why it is that so much earthworm research comes from schools/institutions in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario, due partially to the critical ecological importance of the northern central hardwoods forests as a frontline against worm expansion into boreal environments.

@mi-el-lat I know @cedar-glade already responded to you and it’s worth reposting:

also from cedar-glade, but formatted so the link is clickable:

you can get idea about how gray the knowledge of both invasive earthworms and the effects of potentially invasive predators are from many articles out now a days trying to figure out ecological dynamics of earthworms in any shape or form. https://www.inhs.illinois.edu/resources/inhsreports/may-jun00/worm/

Since a lot of invasive earthworm research and dialogue focuses on the Great Lakes region, we’re in luck because Tumblr might have a resident expert so to speak, since I’m pretty sure @starfoozle specializes in Great Lakes-region invasive species. Regarding “What Can Be Done” to rally community effort, for someone with experience in Midwest landscapes specifically involving citizen science and community engagement with ecology, shout-out to @glumshoe.

And if you’ve got questions about botany, soil, and plant ecology generally, these people are much better scientists than me. They know exactly what they’re talking about and I cannot recommend them highly enough: @spatheandspadix / @botanyshitposts / cedarglade, again ... all of whomst also have firsthand experience with plants and ecosystems of the Midwest and Great Lakes.

Sorry for the long post!

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

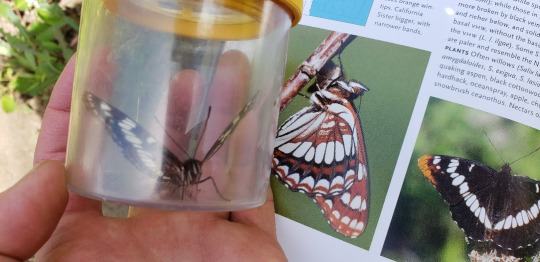

Small Game Hunters: Catching Butterflies in the Pacific Northwest

By: Zach Radmer, USFWS Fish and Wildlife Biologist, Washington Fish and Wildlife Office

Photo: West Coast lady butterfly (Vanessa annabella) at Crater Lake National Park, Oregon; Photo credit: Zach Radmer

“Swoosh!” My net lay still, a colorful quarry perhaps captured after a brief sprint along the trail. Admittedly I’m more excited than you would think. It’s not every day that you catch something new. I don’t think people know that most butterflies get away. The large and sun-warmed individuals are highly motivated and will easily outpace you even into a headwind. I have carried a net for miles and caught nothing but mosquitos. But this time it’s a lustrous copper (Lycaena cupreus) that sports bright orange wings covered in dark black spots. Best of all, I have never caught one before.

Photo: Zach Radmer, biologist and butterfly enthusiast. Photo credit: Jerrmaine Treadwell

This is the part of the story where you think I would wax poetic about chasing butterflies as a kid, but the truth is my professional and personal interest in butterflies didn’t start until my colleagues at the Washington Fish and Wildlife Office introduced me. Butterfly catching is for everyone. Butterfly catching turns every hike or picnic into a scavenger hunt. In an alpine meadow or even a brushy field on the eastern slope of the Cascades you never know what you might find. Visit the same place four months later and you might find an entirely different crew of butterflies. Some fly in spring and some fly in late summer. Some could be ‘on the wing’ all year round because they spend the winter as adults resting in the crevices of trees and houses! Wherever you decide to go looking, bring a lunch. Butterflies are small game and decidedly not delicious.

Photo: Common wood-nymph (Cercyonis pegala) butterfly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS.

Butterfly catching is a cheap sport, and you can take it as seriously as you want (or not). A net and a field guide can be purchased for less than 50 bucks. I prefer Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest by Robert Michael Pyle and Caitlin LaBar. Butterfly nets come in different shapes and sizes and none cost a pretty penny. I use a collapsible net that is easier to backpack with. Unless you have the reflexes of Jackie Chan, a long handle is a good idea too.

There are two endangered butterflies in Washington State, and we like to talk about them a lot (See our web pages on Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly and island marble butterfly).

Photo: Zach in action. Photo credit: Jerrmaine Treadwell

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Washington Fish and Wildlife Office has been involved in butterfly conservation for a few decades. But most people don’t know that 202 butterfly species can be found in Washington and Oregon. Little ones, big ones, spanning just about every color you can think of. Butterflies in Washington and Oregon are sorted in six families, and many of them don’t take any special skills to identify. For example, this is a ‘mud puddle club’ of pale tiger swallowtails and western tiger swallowtails:

The pale wings, large size, and striped wings are unmistakable for anything else. You don’t even have to chase it with net! The western tiger swallowtail (the yellow butterflies in the picture) has a few look-alikes, but only in some portions of the range. If you are butterfly catching in Olympia when you see this one, you know it is very unlikely to be a two-tailed tiger swallowtail or an Oregon swallowtail. Trust me, this isn’t as hard as you think. The Lorquin’s Admiral is another great example of an easy-to-identify butterfly.

Photo: A mud puddle club of swallowtails (both pale and Western). Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

Wherever you’re going, make sure you know which butterflies you should probably let be. A good guidebook will let you know what’s rare and what’s common. This mug shot might look like the federally endangered Taylor’s checkerspot, but it is actually a closely related subspecies (E. e. colonia) that is common in the Cascades:

Butterfly photography is great but some people want to take their small game home. Personally, I don’t collect the butterflies I catch. Butterfly collecting can contribute greatly to our understanding of these species, and collectors have no chance of impacting the abundance of common species. Collecting, pinning, and preserving butterflies is its own set of skills that I won’t address here. Figuring that out will give you something to do when the weather is poor for butterfly chasing.If you are nervous to get started on your own, I personally recommend you check out the Washington Butterfly Association that leads occasional field trips. Experts can help you discover where to look and tricks for telling some groups of butterflies apart. This wild-looking pink-edged sulphur you might assume is unique, but in reality is difficult to pick out of a lineup of other sulphurs.

Lorquin’s Admiral (Limenitis lorquini) buttefly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

There are only a few more things to know before you start. First, catching butterflies is not allowed in National Parks. Not even catch and release. If you must, sign up for the National Park Service’s Cascade Butterfly Project citizen science program to monitor butterflies in the Parks. Second, butterflies should not be moved from where you caught them, and definitely not released outside of their natural range. Butterflies carry diseases and may inappropriately hybridize or compete with closely related species.

Photo: Edith's checkerspot butterfly ( Euphydryas editha colonia), not to be confused for the endangered Taylor's checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori). Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

I will join many other writers on this topic before by saying that the first step in conserving butterflies is to notice them. Where they are, where they aren’t, and what they’re doing. Scientists and enthusiasts can contribute to butterfly conservation by recording what they see and pointing it out to those around them. So grab a net and notebook, and happy hunting.

Pink edged sulphur (Colias interior) butterfly. Photo credit: Zach Radmer, USFWS

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I hope you don't mind me asking because it's not directly dog-related, but I'm considering moving to the Pacific Northwest in the relatively near future and I'm having trouble finding anywhere I could afford to live by myself on an animal care industry salary. I don't need to live in a big city but I don't want to live somewhere that would make it unsafe for me to be openly trans, do you know of any areas in the PNW that are relatively affordable and near some good hiking spots?

I don’t mind at all! I love my state and I’d like to be able to share it with more people! As far as Washington goes, anywhere more than 50 miles away from Seattle or Redmond is definitely going to be a more manageable cost of living. South of Tacoma, or North of Everett would probably be your best bet in terms of cost of living without sacrificing too much when it comes to jobs/pay.

One of the things I absolutely love about my state is that there is no shortage of hiking spots. You could live in Downtown Seattle, and be no more than 30 minutes from dozens of hikes of every level and length. There’s actually even a couple of parks in Seattle city limits that I would consider small hikes.

I would say that most areas on the West side of the mountains are going to be mostly accepting, obviously you’ll find pockets of super conservative people, but usually they’re more worried about local government spending and “personal freedoms” than how a person identifies. The East side of the Cascades would probably be a little more questionable in that regard, it can feel like a completely different world since it’s almost all rural farmland, though there are pockets where I would say it is better. Either Ellensburg, mostly because of CWU, and Spokane are also really nice areas, and quite a bit more progressive than anywhere else in Eastern Washington.

My town is about 30 minutes East of Boeing in Everett, and 45 minutes North of Microsoft in Redmond, and we are definitely on the cusp of what is “affordable” for the area. On one hand, I have not struggled to find an animal services jobs that paid 15-20 dollars an hour. But I HAVE struggled to find housing for under $1000 month. It’s out there, you just need to know where to look, and to avoid the apartment complexes.

I would love to be able to answer any more questions you might have! Shoot me a message and we can talk more. Most of what I have experienced here in Washington also applies to Oregon as well. the cost, the jobs, and difference between West and East sides of the mountains, It’s almost impossible to escape it...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spurlos Verschwunden

You know how you read an article online about scientists trying to find a ways to open portals to other worlds/parallel universes/the Upside Down/etc. and you immediately think: haven’t these scientists ever seen any movie or TV show ever made? They know that’s going to end badly, right? Right??

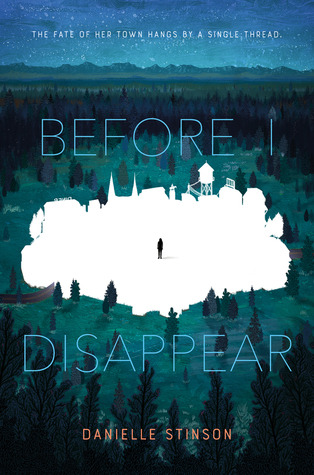

And by that, I mean: Before I Disappear by Danielle Stinson!

Seventeen-year-old Rose Montgomery, her mom Helen and her little brother Charlie have been living on the run for a long time. Rose and Charlie’s father disappeared when Charlie was still a baby and after that, things fell apart. Helen became depressed, and entered into a relationship with an abusive piece of shit referred to only as the Monster. Rose, Helen and Charlie fled the Monster, but he kept pursuing them farther and farther West. At the beginning of the novel, the Montgomerys are lying low in Nevada when Charlie, who has always been a bit strange, insists that the family move West to Fort Glory, Oregon for reasons Rose doesn’t quite understand. When she sees that the charity Hands for Hearths (a definite Habitat for Humanity expy) has an affiliate office in Fort Glory, she decides to go for it. All Rose wants for her family is a permanent home - someplace better than the ramshackle trailer in which they crossed the country. Hands for Hearths is her best hope.

Fort Glory isn’t just your average town on the Oregon Coast - it’s the site of DARC, the Deep Atomic Research Collider, Oregon’s answer to the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. The facility had been shut down, until three weeks ago when it was brought back online...at practically the same moment Charlie started telling Rose that they needed to move to Fort Glory. Spoooooky....

While the Montgomerys adjust to life in Fort Glory, including the influx of tourists, journalists and conspiracy theorists drawn in by DARC, weird things start happening in the town. Crime rises. People randomly go crazy. Rumors are that the DARC is messing with things it shouldn’t be messing with, like poking holes into other dimensions. Because it worked so well on Stranger Things.

Rose just shrugs all this weirdness off - she has bigger problems, like earning a paycheck, helping her family get a house, keeping their ancient truck running and making sure there’s enough food to eat. Charlie, who is clearly some sort of Kid Hero capable of seeing things most other people can’t, tries repeatedly to warn Rose that something bad is about to happen, but, again, she just brushes it off. Rose drives to the nearby town of Maple to the Hands for Hearths office when the whole world goes crazy. The sky turns green, people start attacking each other, even Labrador retrievers turn against their humans! (You know things are truly bad when a Labrador retriever turns against you).

So Rose heads back to Fort Glory as she can as fast only to find that the road literally stops just outside of town. There’s nothing beyond it except old growth forest.

The whole town is gone, along with everyone in it.

Rose, desperate to find her mom and Charlie, runs into the woods. After some shenanigans, she feels this weird tugging...suddenly she’s yanked sideways into a place known as the Fold. The Fold looks like the woods around Fort Glory, but something is wrong. Really, really wrong. Rose quickly teams up with four other teens who have found themselves stuck in the Fold - including the hunky ex-con Ian, whose dark past has made him an outcast in Fort Glory, but as Rose gets to know him, he really doesn’t seem so bad...plus it’s nice to not be alone in the Fold, where the laws of physics don’t apply and your inner demons can physically hurt you. But wormholes and darkness monsters be damned, Rose is going to find Charlie, damn it!

Oh, and her mom. Her, too. It’s not like she forgot her mom was missing, too...

Before I Disappear is a quick, exciting read - it’s also a standalone, which, having read nothing but the first of serieses for a long while, is very refreshing. I love the setting - as a native Oregonian, I am a sucker for stories set in my beloved, bizarre home state. The fictional town of Fort Glory, Oregon seems to be a mix of Fort Clatsop, Fort Stevens and, possibly, Fort Vancouver - you know, all those weird forts they had on the Pacific coast (except Fort Vancouver, which is way down on the Columbia, but the Columbia is how you get down to the coast in a boat so...). All wee little Oregonian children - or, at least, those of us who live west of the Cascades - are forced at some point to go to Fort Clatsop, as it was where Lewis and Clark hung out once they reached the Pacific. I distinctly remember being made to visit Fort Vancouver, too, even though it’s in *shudder* Washington. Fort Glory could also be any of those teeny little coastal towns they have up and down the coast, like Cannon Beach or Seaside or Tillamook or Garibaldi or Nehalem or Manzanita or Netarts or Yachats or Depoe Bay or Newport...ok I should stop because now I’m just naming towns I’ve been to (they’re all very nice. Well, except Newport.The aquarium is cool, but the rest of the town can get sucked into a wormhole for all I care).

Needless to say, I am familiar with the Oregon Coast, it’s where Oregonians go when the sun comes out. (Well, when the sun comes out in the rest of the state. On the coast, the sun only comes out three days a year and it’s always on the days when you aren’t there). So I can speak with some authority when I say the Oregon Coast would be a terrible place to build a fancy underground atomic energy research facility-type thing. I mean, there’s the risk of tsunamis, earthquakes, lingering radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi Power plant Disaster of 2011...

See, this is why we shouldn’t have research facilities dedicated to punching holes into other dimensions situated on the Oregon Coast. Especially not right on top of a town. Put that shit out in the desert where if you poke a hole and let in a Demogorgon or a Darkness Monster, there’s not much around for it to eat. Except desert.

Also, I’m fairly certain any contact with other dimensions will go something like this:

But back to the book: character-wise, the one character we get to know best is Rose, which makes sense as the novel is written from her first-person perspective. Unfortunately, we don’t get to know the side characters as well - Blaine, Becca, and Jeremy aren’t nearly as well-developed. Charlie, aside from being a mysterious child who can see into other dimensions, doesn’t have much of a personality. He’s just an odd kid and Rose absolutely adores him. Rose’s mom falls by the wayside entirely - most of the novel has Rose laser-focused on finding Charlie, while her mom is a bit of an afterthought. But, again, that’s the limitation of the first-person perspective. Aside from Rose, the most developed character is Ian, who apparently has starburst eyes.

Both he and Rose are on the run from their pasts, and being in the Fold is forcing them to confront some pretty harsh truths about themselves and their lives.

My biggest complaint concerning Before I Disappear would be the ending. The story just ends. I would’ve loved a denouement or an epilogue or something where we could see what happens to the characters after the end of the main action...but instead we get action action action action end. So many stories end that way, I wanna know what people get up to when they get home after the adventure, damn it! I’m guessing lots of people, as soon as the adventure is over, just go home, shower, stuff food into their faces and then sleep for the next three straight days. Or maybe go to a hospital. Or immediately get arrested, like in Keanu. Either way, I wish we could’ve gotten more than just “hey it’s over!”

RECOMMENDED FOR: Anyone just fresh off a binge of season 3 of Stranger Things and are desperate for another cool inter-dimensional teen drama involving mysterious research facilities, wormholes and disappearing towns. Also fans of YA genre stories and Oregonians.

NOT RECOMMENDED FOR: non-YA fans, anyone currently living on the Oregon Coast, scientists currently working at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland.

RATING: 3.99/5 (0.1 point removed for the abrupt ending. I wanted more! *cries*)

RELEASE DATE: July 23, 2019 (Ha! I got this review done on time!!)

THE GORGEOUS OREGON COAST:

FOR ANYONE CONFUSED ABOUT THE TITLE OF THIS REVIEW: Learn some German.

#before i disappear#danielle stinson#ya#book review#ya science fiction#ya sci fi#parallel world#the upside down#string theory#young adult science fiction#parallel universe#wormhole#ya fantasy#oregon coast#books set in oregon#oregon in fiction#oregon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most WOW-worthy Sections of the PCT in Washington

This is an excerpt of a longer article published in The Seattle Times several years ago. Sometimes Washington gets overshadowed by the excitement of the first weeks on the trail in the desert south and the majesty of the High Sierra, but some of the most stunning mileage along the trail comes in the final 500 miles. It can be cold and wet in late September and October (often when thru-hikers are headed to the finish line) but glorious in July and August … a great time to hike in Washington. (There is beauty in the snow too!)

I completely agree with this assessment walking Washington’s PCT.

By Terry Wood, Seattle Times

So what sections are the trail’s best in Washington? I’ve hiked more than two-thirds of the state’s PCT miles, making repeat visits to prime sections, and my “best-of” list is a four-way tie (details in a moment).

Others offer tips on least-favorite stretches. Author Doug Lorain considers two sections marginal: from the Oregon border north to Mount Adams (where first power lines, then heavy forest, diminish views, though the Indian Heaven Wilderness west of Trout Lake rates applause), and a long stretch of miles south of Snoqualmie Pass.

“A lot of checkerboards,” hiker Mike McCarty says of Snoqualmie Pass south, referring to patches of intermittently harvested forest. His threesome walked the 22 miles between Stampede Pass and Interstate 90 as a long, call-of-duty day hike. A ray of hope: A land sale announced in March could lead to a rerouting of part of that trail. Good news, says McCarty. “For about five miles south of Snoqualmie Pass, it’s crappy trail,” he says.

Now my idea of the good stuff:

• Mount Adams (Forest Service Road 23) north to White Pass (U.S. Highway 12), 66 miles.

The westside portion of Mount Adams’ Highline Trail also doubles as the PCT and is, as McCarty correctly points out, a gorgeous area. Bonus: This portion of trail is relatively level for miles.

The section’s showstopper, though, is the Goat Rocks Wilderness and the rocky, barren, narrow path the PCT follows over the shoulder of 7,880-foot Old Snowy. Though harrowing to people uncomfortable with heights and steep drop-offs, this section’s sky-high views northwest to Rainier and south to Adams are memory-makers.

In “Trekking Washington” Mike Woodmansee outlines a good game plan for catching three of the region’s major highlights (Cispus Basin, the climb to Old Snowy and Shoe Lake): a 30-mile, one-way push from remote Walupt Lake to White Pass. The downside: A required 50-mile car shuttle that runs through Packwood, with more than a third of the drive on dirt road.

• Snoqualmie Pass (I-90) to Stevens Pass (U.S. Highway 2), 71 miles.

Due to the almost legendary appeal of the Kendall Katwalk — a narrow stretch of trail that was dynamited into existence along a steep granite slope six miles north of Snoqualmie Pass — a bazillion curious urban day hikers have been able to claim they have experienced at least a taste of the Pacific Crest Trail.

With its big views, not-so-easy approach (2,600-foot elevation gain) and hint of danger, a hike to the Katwalk (starting at the PCT trailhead just north of Exit 52 on I-90) is a worthwhile teaser to what makes the PCT so appealing.

More treasures lie farther north: the rugged Chikamin Ridge and Park Lakes; bedazzling Spectacle Lake (often approached by overnight backpackers from Cle Elum); Cathedral Rock; Deception Pass, the knockout view of Glacier Lake (with Glacier Peak looming far to the north) from Pieper Pass.

A one-way, pass-to-pass jaunt is great fun for low-weight, high-speed backpackers searching for a challenge. I once covered the 71 miles in three days, another time in four. Even if you take the customary seven days, it’s a rewarding way to get an in-depth look at Seattle’s next-door mountains.

• Stevens Pass (U.S. 2) to Rainy Pass (Highway 20), 127 miles.

The longest and toughest section of the PCT, with multiple lung-busting climbs and sharp descents, may also be its prettiest. As author Romano says, the meadows (and berry patches) along this stretch are uncommonly lovely. From Kodak Peak north to White Pass and Red Pass, the PCT sends hikers soaring along a towering ridgeline.

And the hits just keep coming. “When you start at Stevens, Glacier Peak is constantly up ahead, like a beacon, luring you in the entire way,” Romano says. “It’s the wildest of the Washington Cascade volcanoes. After miles of meadows, you come to Red Pass, and Glacier is suddenly right in your face.

Beyond Red Pass, now you go through alpine tundra and past a cinder cone (White Chuck Cinder Cone) that’s one of the coolest cinder cones outside of Lassen Volcanic National Park. Then you swing around Glacier Peak and head up to Fire Creek Pass and eventually Miners Ridge and Suiattle Pass. It’s just a great area.”

• Rainy Pass (Highway 20) to Canadian border, 61 miles.

The most common introduction to this area is the day hike from Rainy Pass to gorgeous, 6,800-foot Cutthroat Pass (10 miles round-trip, 2,000-foot elevation gain). Tip: Venture even farther north, to Granite Pass, and take in the long-distance view of Golden Horn and mighty Tower Mountain.

Or drive the primitive, winding, not-for-the-timid Harts Pass Road (built in 1893; recently reopened after a rockfall was cleared) to Harts Pass and either walk south to expansive Grasshopper Pass, or north 3.5 miles to Windy Pass while gawking at the high-density cluster of peaks to the west, including imposing Azurite Peak and Mount Ballard.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cynoglossum grande

Cynoglossum grande Douglas ex Lehm.

Pacific Hound's Tongue

Boraginaceae (Borage Family)

Synonym(s):

USDA Symbol: CYGR

USDA Native Status: L48 (N)

Several smooth stems with large, ovate, long-stalked leaves mostly near base and loose clusters of purple or blue flowers on branches at top.The common name refers to the shape of the broad leaves. Native Americans used preparations from the root to treat burns and stomachaches. There are several species, all with blue to purple or maroon flowers and large rough nutlets that stick to clothing.

Plant characteristics

Duration: Perennial

Habit: Herb

Bloom Time: Mar , Apr , May , Jun

Distribution

USA: CA , OR , WA

Native Distribution: Western Washington south to southern California.

Native Habitat: Dry shaded places in woods.

The uniquely intense blue flower color, with distinct white center, may have evolved to help pollinators zero in on the pollen, helping aid it’s own pollination. Hound’s tongue attracts native bees and hummingbirds and is an occasional larval host plant for moths and butterflies. Native plants that grow in dry, shady environments are not easy to find for a garden setting, but hound’s tongue is perfect for such a location. Having a large taproot, hound’s tongue does best with little or no supplemental water, but will tolerate some summer water with good drainage. After flowering and setting seed, hound’s tongue goes completely dormant in the summer, an adaptation for survival during the dry summer months.

The vivid blue flowers of hound’s tongue will fade into a lovely lavender color as it gets close to setting seed. The seed has evolved hook-like appendages on the seed coat that grab onto and attach to anything nearby, including animals or human socks. This seed dispersal tactic works great and has helped the distribution of hound’s tongue.

We have found hound’s tongue to be an easy plant to encourage, grow and propagate in oak woodland and mixed conifer forest on our own land. The best method we have found has been planting hound’s tongue seed into the site of a burn pile after burning debris from forest health thinning. Once the small, circular burn pile has cooled — or even if it was burned a year ago — you can seed hound’s tongue into the ash in the winter, and come spring you will have a circle of hound’s tongue sprouts! They do well in this setting that mimics natural fire disturbance, where there is little competition and wonderfully mineral-rich soil to help nourish the small seedlings.Hound’s tongue can also be seeded into containers and grown out for a season before transplanting into your preferred location, or direct sown into a dry shady spot without too much competing vegetation.Hound’s tongue ranges from British Columbia south to San Luis Obispo county in California. In Oregon it occurs only on the west side of the Cascade Mountains, except in the Columbia River Gorge.

When hound’s tongue is flowering that is a sign that the morel mushrooms are also emerging from the low-elevation chaparral and oak woodland communities. Spring is on!

0 notes

Text

The Really Big One

By Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, July 20, 2015 Issue

When the 2011 earthquake and tsunami struck Tohoku, Japan, Chris Goldfinger was two hundred miles away, in the city of Kashiwa, at an international meeting on seismology. As the shaking started, everyone in the room began to laugh. Earthquakes are common in Japan--that one was the third of the week--and the participants were, after all, at a seismology conference. Then everyone in the room checked the time.

Seismologists know that how long an earthquake lasts is a decent proxy for its magnitude. The 1989 earthquake in Loma Prieta, California, which killed sixty-three people and caused six billion dollars’ worth of damage, lasted about fifteen seconds and had a magnitude of 6.9. A thirty-second earthquake generally has a magnitude in the mid-sevens. A minute-long quake is in the high sevens, a two-minute quake has entered the eights, and a three-minute quake is in the high eights. By four minutes, an earthquake has hit magnitude 9.0.

When Goldfinger looked at his watch, it was quarter to three. The conference was wrapping up for the day. He was thinking about sushi. The speaker at the lectern was wondering if he should carry on with his talk. The earthquake was not particularly strong. Then it ticked past the sixty-second mark, making it longer than the others that week. The shaking intensified. The seats in the conference room were small plastic desks with wheels. Goldfinger, who is tall and solidly built, thought, No way am I crouching under one of those for cover. At a minute and a half, everyone in the room got up and went outside.

It was March. There was a chill in the air, and snow flurries, but no snow on the ground. Nor, from the feel of it, was there ground on the ground. The earth snapped and popped and rippled. It was, Goldfinger thought, like driving through rocky terrain in a vehicle with no shocks, if both the vehicle and the terrain were also on a raft in high seas. The quake passed the two-minute mark. The trees, still hung with the previous autumn’s dead leaves, were making a strange rattling sound. The flagpole atop the building he and his colleagues had just vacated was whipping through an arc of forty degrees. The building itself was base-isolated, a seismic-safety technology in which the body of a structure rests on movable bearings rather than directly on its foundation. Goldfinger lurched over to take a look. The base was lurching, too, back and forth a foot at a time, digging a trench in the yard. He thought better of it, and lurched away. His watch swept past the three-minute mark and kept going.

Oh, s--t, Goldfinger thought, although not in dread, at first: in amazement. For decades, seismologists had believed that Japan could not experience an earthquake stronger than magnitude 8.4. In 2005, however, at a conference in Hokudan, a Japanese geologist named Yasutaka Ikeda had argued that the nation should expect a magnitude 9.0 in the near future--with catastrophic consequences, because Japan’s famous earthquake-and-tsunami preparedness, including the height of its sea walls, was based on incorrect science. The presentation was met with polite applause and thereafter largely ignored. Now, Goldfinger realized as the shaking hit the four-minute mark, the planet was proving the Japanese Cassandra right.

For a moment, that was pretty cool: a real-time revolution in earthquake science. Almost immediately, though, it became extremely uncool, because Goldfinger and every other seismologist standing outside in Kashiwa knew what was coming. One of them pulled out a cell phone and started streaming videos from the Japanese broadcasting station NHK, shot by helicopters that had flown out to sea soon after the shaking started. Thirty minutes after Goldfinger first stepped outside, he watched the tsunami roll in, in real time, on a two-inch screen.

In the end, the magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami killed more than eighteen thousand people, devastated northeast Japan, triggered the meltdown at the Fukushima power plant, and cost an estimated two hundred and twenty billion dollars. The shaking earlier in the week turned out to be the foreshocks of the largest earthquake in the nation’s recorded history. But for Chris Goldfinger, a paleoseismologist at Oregon State University and one of the world’s leading experts on a little-known fault line, the main quake was itself a kind of foreshock: a preview of another earthquake still to come.

Most people in the United States know just one fault line by name: the San Andreas, which runs nearly the length of California and is perpetually rumored to be on the verge of unleashing “the big one.” That rumor is misleading, no matter what the San Andreas ever does. Every fault line has an upper limit to its potency, determined by its length and width, and by how far it can slip. For the San Andreas, one of the most extensively studied and best understood fault lines in the world, that upper limit is roughly an 8.2--a powerful earthquake, but, because the Richter scale is logarithmic, only six per cent as strong as the 2011 event in Japan.

Just north of the San Andreas, however, lies another fault line. Known as the Cascadia subduction zone, it runs for seven hundred miles off the coast of the Pacific Northwest, beginning near Cape Mendocino, California, continuing along Oregon and Washington, and terminating around Vancouver Island, Canada. The “Cascadia” part of its name comes from the Cascade Range, a chain of volcanic mountains that follow the same course a hundred or so miles inland. The “subduction zone” part refers to a region of the planet where one tectonic plate is sliding underneath (subducting) another. Tectonic plates are those slabs of mantle and crust that, in their epochs-long drift, rearrange the earth’s continents and oceans. Most of the time, their movement is slow, harmless, and all but undetectable. Occasionally, at the borders where they meet, it is not.

Take your hands and hold them palms down, middle fingertips touching. Your right hand represents the North American tectonic plate, which bears on its back, among other things, our entire continent, from One World Trade Center to the Space Needle, in Seattle. Your left hand represents an oceanic plate called Juan de Fuca, ninety thousand square miles in size. The place where they meet is the Cascadia subduction zone. Now slide your left hand under your right one. That is what the Juan de Fuca plate is doing: slipping steadily beneath North America. When you try it, your right hand will slide up your left arm, as if you were pushing up your sleeve. That is what North America is not doing. It is stuck, wedged tight against the surface of the other plate.

Without moving your hands, curl your right knuckles up, so that they point toward the ceiling. Under pressure from Juan de Fuca, the stuck edge of North America is bulging upward and compressing eastward, at the rate of, respectively, three to four millimetres and thirty to forty millimetres a year. It can do so for quite some time, because, as continent stuff goes, it is young, made of rock that is still relatively elastic. (Rocks, like us, get stiffer as they age.) But it cannot do so indefinitely. There is a backstop--the craton, that ancient unbudgeable mass at the center of the continent--and, sooner or later, North America will rebound like a spring. If, on that occasion, only the southern part of the Cascadia subduction zone gives way--your first two fingers, say--the magnitude of the resulting quake will be somewhere between 8.0 and 8.6. That’s the big one. If the entire zone gives way at once, an event that seismologists call a full-margin rupture, the magnitude will be somewhere between 8.7 and 9.2. That’s the very big one.

Flick your right fingers outward, forcefully, so that your hand flattens back down again. When the next very big earthquake hits, the northwest edge of the continent, from California to Canada and the continental shelf to the Cascades, will drop by as much as six feet and rebound thirty to a hundred feet to the west--losing, within minutes, all the elevation and compression it has gained over centuries. Some of that shift will take place beneath the ocean, displacing a colossal quantity of seawater. (Watch what your fingertips do when you flatten your hand.) The water will surge upward into a huge hill, then promptly collapse. One side will rush west, toward Japan. The other side will rush east, in a seven-hundred-mile liquid wall that will reach the Northwest coast, on average, fifteen minutes after the earthquake begins. By the time the shaking has ceased and the tsunami has receded, the region will be unrecognizable. Kenneth Murphy, who directs fema’s Region X, the division responsible for Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Alaska, says, “Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast.”

In the Pacific Northwest, the area of impact will cover* some hundred and forty thousand square miles, including Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, Eugene, Salem (the capital city of Oregon), Olympia (the capital of Washington), and some seven million people. When the next full-margin rupture happens, that region will suffer the worst natural disaster in the history of North America. Roughly three thousand people died in San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake. Almost two thousand died in Hurricane Katrina. Almost three hundred died in Hurricane Sandy. FEMA projects that nearly thirteen thousand people will die in the Cascadia earthquake and tsunami. Another twenty-seven thousand will be injured, and the agency expects that it will need to provide shelter for a million displaced people, and food and water for another two and a half million. “This is one time that I’m hoping all the science is wrong, and it won’t happen for another thousand years,” Murphy says.

In fact, the science is robust, and one of the chief scientists behind it is Chris Goldfinger. Thanks to work done by him and his colleagues, we now know that the odds of the big Cascadia earthquake happening in the next fifty years are roughly one in three. The odds of the very big one are roughly one in ten. Even those numbers do not fully reflect the danger--or, more to the point, how unprepared the Pacific Northwest is to face it. The truly worrisome figures in this story are these: Thirty years ago, no one knew that the Cascadia subduction zone had ever produced a major earthquake. Forty-five years ago, no one even knew it existed.

In May of 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, together with their Corps of Discovery, set off from St. Louis on America’s first official cross-country expedition. Eighteen months later, they reached the Pacific Ocean and made camp near the present-day town of Astoria, Oregon. The United States was, at the time, twenty-nine years old. Canada was not yet a country. The continent’s far expanses were so unknown to its white explorers that Thomas Jefferson, who commissioned the journey, thought that the men would come across woolly mammoths. Native Americans had lived in the Northwest for millennia, but they had no written language, and the many things to which the arriving Europeans subjected them did not include seismological inquiries. The newcomers took the land they encountered at face value, and at face value it was a find: vast, cheap, temperate, fertile, and, to all appearances, remarkably benign.

A century and a half elapsed before anyone had any inkling that the Pacific Northwest was not a quiet place but a place in a long period of quiet. It took another fifty years to uncover and interpret the region’s seismic history. Geology, as even geologists will tell you, is not normally the sexiest of disciplines. But, sooner or later, every field has its field day, and the discovery of the Cascadia subduction zone stands as one of the greatest scientific detective stories of our time.

The first clue came from geography. Almost all of the world’s most powerful earthquakes occur in the Ring of Fire, the volcanically and seismically volatile swath of the Pacific that runs from New Zealand up through Indonesia and Japan, across the ocean to Alaska, and down the west coast of the Americas to Chile. Japan, 2011, magnitude 9.0; Indonesia, 2004, magnitude 9.1; Alaska, 1964, magnitude 9.2; Chile, 1960, magnitude 9.5--not until the late nineteen-sixties, with the rise of the theory of plate tectonics, could geologists explain this pattern. The Ring of Fire, it turns out, is really a ring of subduction zones. Nearly all the earthquakes in the region are caused by continental plates getting stuck on oceanic plates--as North America is stuck on Juan de Fuca--and then getting abruptly unstuck. And nearly all the volcanoes are caused by the oceanic plates sliding deep beneath the continental ones, eventually reaching temperatures and pressures so extreme that they melt the rock above them.

The Pacific Northwest sits squarely within the Ring of Fire. Off its coast, an oceanic plate is slipping beneath a continental one. Inland, the Cascade volcanoes mark the line where, far below, the Juan de Fuca plate is heating up and melting everything above it. In other words, the Cascadia subduction zone has, as Goldfinger put it, “all the right anatomical parts.” Yet not once in recorded history has it caused a major earthquake--or, for that matter, any quake to speak of. By contrast, other subduction zones produce major earthquakes occasionally and minor ones all the time: magnitude 5.0, magnitude 4.0, magnitude why are the neighbors moving their sofa at midnight. You can scarcely spend a week in Japan without feeling this sort of earthquake. You can spend a lifetime in many parts of the Northwest--several, in fact, if you had them to spend--and not feel so much as a quiver. The question facing geologists in the nineteen-seventies was whether the Cascadia subduction zone had ever broken its eerie silence.

In the late nineteen-eighties, Brian Atwater, a geologist with the United States Geological Survey, and a graduate student named David Yamaguchi found the answer, and another major clue in the Cascadia puzzle. Their discovery is best illustrated in a place called the ghost forest, a grove of western red cedars on the banks of the Copalis River, near the Washington coast. When I paddled out to it last summer, with Atwater and Yamaguchi, it was easy to see how it got its name. The cedars are spread out across a low salt marsh on a wide northern bend in the river, long dead but still standing. Leafless, branchless, barkless, they are reduced to their trunks and worn to a smooth silver-gray.

What killed the trees in the ghost forest was saltwater. It had long been assumed that they died slowly, as the sea level around them gradually rose and submerged their roots. But, by 1987, Atwater, who had found in soil layers evidence of sudden land subsidence along the Washington coast, suspected that that was backward--that the trees had died quickly when the ground beneath them plummeted. To find out, he teamed up with Yamaguchi, a specialist in dendrochronology, the study of growth-ring patterns in trees. Yamaguchi took samples of the cedars and found that they had died simultaneously: in tree after tree, the final rings dated to the summer of 1699. Since trees do not grow in the winter, he and Atwater concluded that sometime between August of 1699 and May of 1700 an earthquake had caused the land to drop and killed the cedars. That time frame predated by more than a hundred years the written history of the Pacific Northwest--and so, by rights, the detective story should have ended there.

But it did not. If you travel five thousand miles due west from the ghost forest, you reach the northeast coast of Japan. As the events of 2011 made clear, that coast is vulnerable to tsunamis, and the Japanese have kept track of them since at least 599 A.D. In that fourteen-hundred-year history, one incident has long stood out for its strangeness. On the eighth day of the twelfth month of the twelfth year of the Genroku era, a six-hundred-mile-long wave struck the coast, levelling homes, breaching a castle moat, and causing an accident at sea. The Japanese understood that tsunamis were the result of earthquakes, yet no one felt the ground shake before the Genroku event. The wave had no discernible origin. When scientists began studying it, they called it an orphan tsunami.

Finally, in a 1996 article in Nature, a seismologist named Kenji Satake and three colleagues, drawing on the work of Atwater and Yamaguchi, matched that orphan to its parent--and thereby filled in the blanks in the Cascadia story with uncanny specificity. At approximately nine o’ clock at night on January 26, 1700, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck the Pacific Northwest, causing sudden land subsidence, drowning coastal forests, and, out in the ocean, lifting up a wave half the length of a continent. It took roughly fifteen minutes for the Eastern half of that wave to strike the Northwest coast. It took ten hours for the other half to cross the ocean. It reached Japan on January 27, 1700: by the local calendar, the eighth day of the twelfth month of the twelfth year of Genroku.

Once scientists had reconstructed the 1700 earthquake, certain previously overlooked accounts also came to seem like clues. In 1964, Chief Louis Nookmis, of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation, in British Columbia, told a story, passed down through seven generations, about the eradication of Vancouver Island’s Pachena Bay people. “I think it was at nighttime that the land shook,” Nookmis recalled. According to another tribal history, “They sank at once, were all drowned; not one survived.” A hundred years earlier, Billy Balch, a leader of the Makah tribe, recounted a similar story. Before his own time, he said, all the water had receded from Washington State’s Neah Bay, then suddenly poured back in, inundating the entire region. Those who survived later found canoes hanging from the trees. In a 2005 study, Ruth Ludwin, then a seismologist at the University of Washington, together with nine colleagues, collected and analyzed Native American reports of earthquakes and saltwater floods. Some of those reports contained enough information to estimate a date range for the events they described. On average, the midpoint of that range was 1701.

The reconstruction of the Cascadia earthquake of 1700 is one of those rare natural puzzles whose pieces fit together as tectonic plates do not: perfectly. It is wonderful science. It was wonderful for science. And it was terrible news for the millions of inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest. As Goldfinger put it, “In the late eighties and early nineties, the paradigm shifted to ‘uh-oh.’”

Goldfinger told me this in his lab at Oregon State. Thanks to his work, we now know that the Pacific Northwest has experienced forty-one subduction-zone earthquakes in the past ten thousand years. If you divide ten thousand by forty-one, you get two hundred and forty-three, which is Cascadia’s recurrence interval: the average amount of time that elapses between earthquakes. That timespan is dangerous both because it is too long--long enough for us to unwittingly build an entire civilization on top of our continent’s worst fault line--and because it is not long enough. Counting from the earthquake of 1700, we are now three hundred and fifteen years into a two-hundred-and-forty-three-year cycle.

It is possible to quibble with that number. Recurrence intervals are averages, and averages are tricky: ten is the average of nine and eleven, but also of eighteen and two. It is not possible, however, to dispute the scale of the problem. The devastation in Japan in 2011 was the result of a discrepancy between what the best science predicted and what the region was prepared to withstand. The same will hold true in the Pacific Northwest--but here the discrepancy is enormous. “The science part is fun,” Goldfinger says. “And I love doing it. But the gap between what we know and what we should do about it is getting bigger and bigger, and the action really needs to turn to responding. Otherwise, we’re going to be hammered. I’ve been through one of these massive earthquakes in the most seismically prepared nation on earth. If that was Portland”--Goldfinger finished the sentence with a shake of his head before he finished it with words. “Let’s just say I would rather not be here.”

The first sign that the Cascadia earthquake has begun will be a compressional wave, radiating outward from the fault line. Compressional waves are fast-moving, high-frequency waves, audible to dogs and certain other animals but experienced by humans only as a sudden jolt. They are not very harmful, but they are potentially very useful, since they travel fast enough to be detected by sensors thirty to ninety seconds ahead of other seismic waves. That is enough time for earthquake early-warning systems, such as those in use throughout Japan, to automatically perform a variety of lifesaving functions: shutting down railways and power plants, opening elevators and firehouse doors, alerting hospitals to halt surgeries, and triggering alarms so that the general public can take cover. The Pacific Northwest has no early-warning system. When the Cascadia earthquake begins, there will be, instead, a cacophony of barking dogs and a long, suspended, what-was-that moment before the surface waves arrive. Surface waves are slower, lower-frequency waves that move the ground both up and down and side to side: the shaking, starting in earnest.