#warren g harding

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

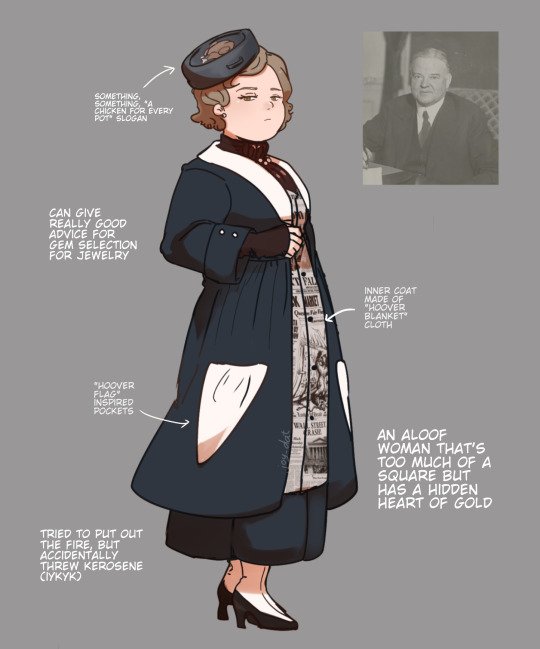

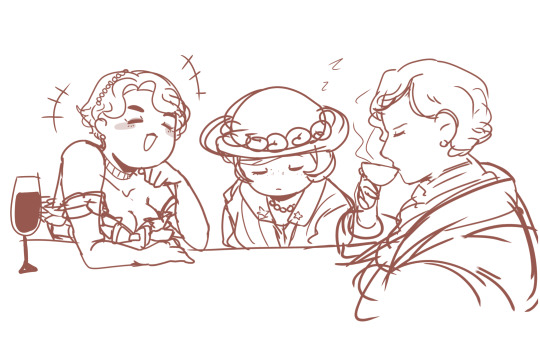

the roaring twenties 🥂

needed a slight breather from studying, so i continued some of my anime girl president doodles

(aight, back to studying and my hiatus)

context of these doodles is in the captions of this post.

also credit to @tinytimism for suggesting me to make harding

#cursed anime girlification(?)#us presidents#us history#warren g harding#calvin coolidge#herbert hoover#shitpost

144 notes

·

View notes

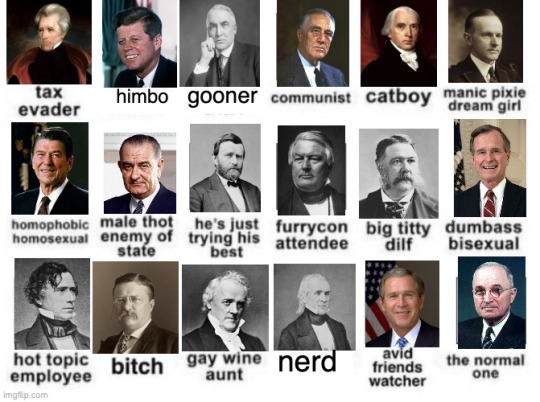

Text

I'm probably extremely right and extremely wrong

#presidents#meme#andrew jackson#john f kennedy#warren g harding#franklin roosevelt#james madison#calvin coolidge#ronald reagan#lyndon b johnson#ulysses s grant#millard fillmore#chester arthur#george hw bush#franklin pierce#theodore roosevelt#james buchanan#james k polk#george w bush#harry truman

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two post in one edition from my main

Found these cool presentations on my fyp back in August. As someone who loves pop culture and had special interests on US presidents, all of them are on point!

#american history#us history#us presidents#dwight eisenhower#bill clinton#george washington#gerald ford#andrew jackson#james madison#james k polk#william mckinley#jimmy carter#grover cleveland#warren g harding#warren harding#theodore roosevelt#teddy roosevelt#james monroe#ronald reagan#calvin coolidge#fdr#franklin d. roosevelt

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

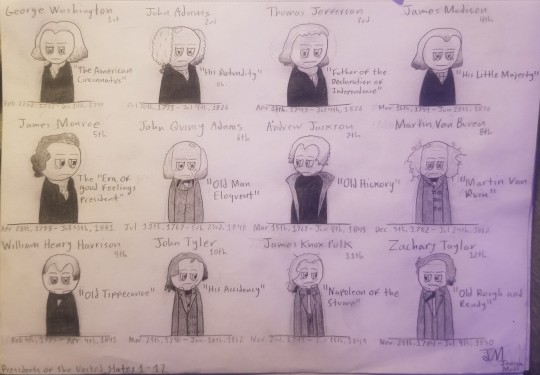

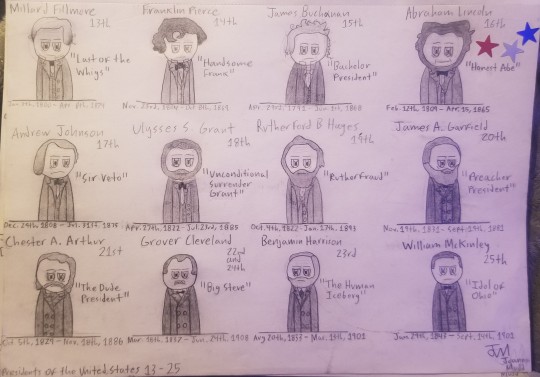

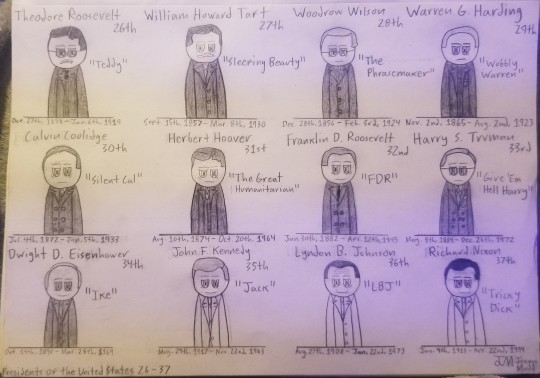

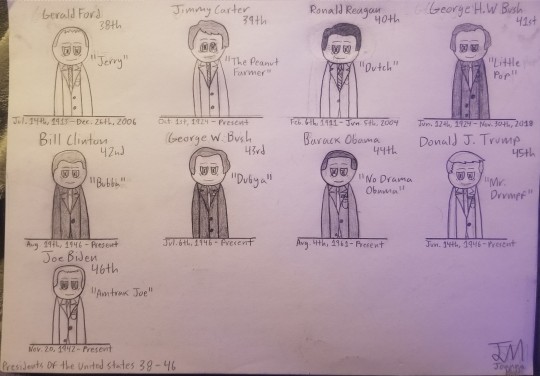

I drew the US Presidents ⁉️⁉️

Constructive criticism is not allowed ⁉️⁉️(Because I only draw for fun lol, not mad or anything tho)

I couldn't tag anymore presidents 💔💔

#u.s. presidents#george washington#john adams#thomas jefferson#james madison#james monroe#john quincy adams#andrew jackson#martin van buren#william henry harrison#john tyler#james k polk#zachary taylor#millard fillmore#franklin pierce#james buchanan#abraham lincoln#andrew johnson#ulysses s grant#rutherford b hayes#james a garfield#chester a arthur#grover cleveland#benjamin harrison#william mckinley#theodore roosevelt#william howard taft#woodrow wilson#warren g harding#calvin coolidge

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

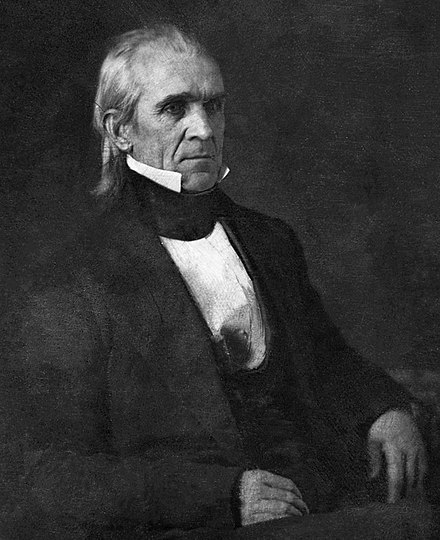

are we manifesting our destiny or returning to normalcy today because HOLY SHIT WE HAVE TWOOOOOO BIRTHDAAAAAYYYYYSSSSSSSSS

#us presidents#presidents#james k polk#warren g harding#i find this to be a very Nice and Awesome coincident

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Presidents Day AI pt 2

#presidents day#us presidents#lyndon b. johnson#john f kennedy#dwight d. eisenhower#harry s truman#franklin d. roosevelt#herbert hoover#calvin coolidge#warren g harding#woodrow wilson#william howard taft#ai generated

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

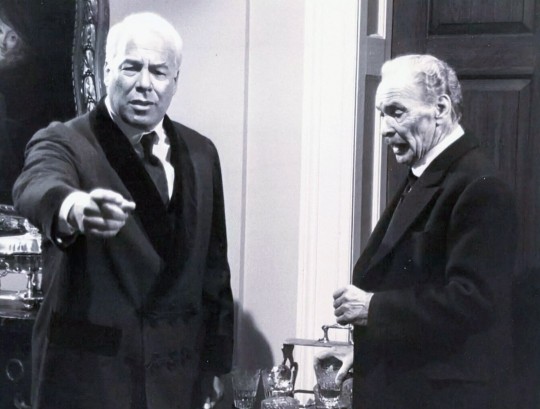

George Kennedy, as President Warren G. Harding, and Barry Sullivan in a production still for Backstairs At The White House (1979)

#george kennedy#barry sullivan#backstairs at the white house#1979#warren g harding#hollywood#old hollywood#classic hollywood#classic television#70s movies#70s tv#tv mini series

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Poll#President#Presidents#President of the United States#US President#Presidentail Poll#America#Tumblr Poll#Tournament Poll#Warren G Harding#Herbert Hoover#Note: we do NOT own this artwork

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

-Warren G Harding, 29th President

she easy on my peasy till i lemon squeezy

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Check out "Lyrical Gangbang" [Explicit] by Dr. Dre on Amazon Music

https://music.amazon.com/albums/B0BT4TMZYS?trackAsin=B0BT4SPK5K&do=play&ts=1746749075&ref=dm_sh_TDtXwHyQVwbXlJAs2mAcyw8dU&referrer : @ladyofrage94

@kurupt_gotti @KuruptHD @rbx #RBX @drdre @deathrowrecords

#youtube#free palestine#palestine#free palestine 🇵🇸#fromtherivertothesea#genocide#cry freedom#from the river to the sea 🇵🇸#gaza westbank jerusalem palestine#rbx#gangster#lady of rage#bushwick#snoop dogg#snoopy#snoop doog#warren g harding#kurupt#daz#death row records#warreng

0 notes

Text

US 1930 1½¢ Warren G. Harding (1865 - 1923), 29th President of the USA

#us#usa#1930s#men#politicans#us presidents#presidents#warren g harding#stamp#stamps#philately#stamp collection#snail mail#postage#postage stamp#usps

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

your series of anime girl-ified presidents is so good they feel like something out of a themed trading card or gacha game in the best way

awieee i'm glad you like them hehe 💗💗💗

as a side treat, here's a compilation of my latest progressive era pretties 😊💗

#ask stuff#cursed anime girlification(?)#us history#us presidents#theodore roosevelt#teddy roosevelt#franklin d. roosevelt#william mckinley#william howard taft#woodrow wilson#warren g harding#calvin coolidge#herbert hoover

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

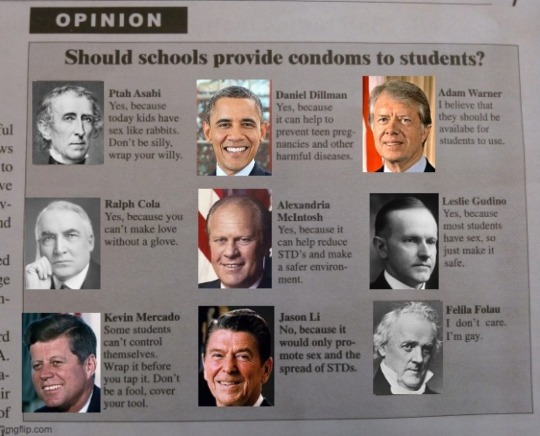

Something I made ages ago

#presidents#john tyler#barack obama#jimmy carter#warren g harding#gerald ford#calvin coolidge#john f kennedy#ronald reagan#james buchanan

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

hold the phone

just learned that the G. in Warren G. Harding stood for:

Gamaliel

the middle name from middle earth!!

1 note

·

View note

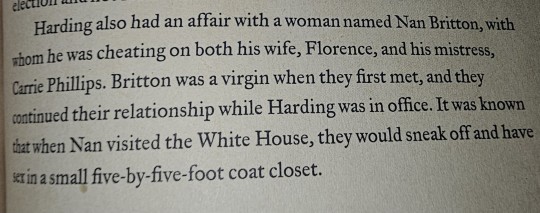

Text

#warren g harding#history geek#real life#american history#stupid american history#leland gregory#american presidents

0 notes

Text

...hh es a little offputtinh

13 notes

·

View notes