#vitellius

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On 24 September 15 AD, Aulus Vitellius, one of the emperors from 69 AD (the year of 4 Emperors) was born. Here are some facts about Vitellius:

When his parents saw his horoscope, they were so horrified they tried to keep him from governing a province or commanding an army.

In his youth, he was a guest of Emperor Tiberius on Capri and the most malicious rumors say that he was one of the emperor's tiddlers - boys trained to sexually please him - which in turn won political advancement to Aulus's father Lucius.

Galba named Vitellius commander of the Rhine legions because he believed he was too lazy and incompetent to lead a rebellion and declare himself emperor.

He was the only one who didn't take the name Caesar as part of his regnal name, choosing Germanicus instead.

He allegedly feasted four times a day. Extravagant dishes like pheasant brains and flamingo tongues were served at these feasts.

When his army was defeated by Vespasian's legions, he tried to abdicate but his supporters wouldn't let him.

After his final defeat, he tried to hide but was dragged by an angry jeering mob to Gemonian stairs and savagely killed. His head was then paraded through the streets of Rome and his body was thrown into the Tiber.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ClassicsTober24 Day 26. Vitellius

Picked by Dr Rob Cromarty, Ancient Historian, Archaeologist, and Teacher

#classicstober#classicstober24#tagamemnon#ancient history#roman history#Vitellius#year of the four emperors

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

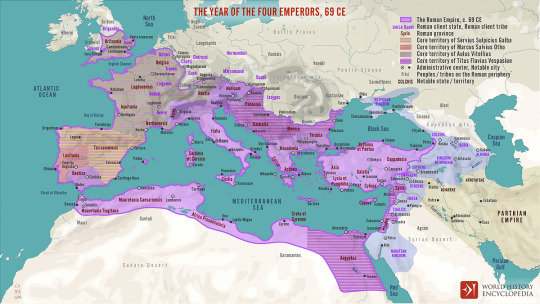

The Year of the Four Emperors, 69 CE

A map illustrating the fluctuation of powers in the Roman Empire during 69 CE (also known as The Year of the Four Emperors,) a turbulent period in Roman history that involved the rapid succession of Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian as emperors riding on personal ambition, political instability, power struggles, and military conflicts.

Image by Simeon Netchev

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

What became of Pilate?

Unfortunately, his encounter with Christ left him an unchanged man. According to Josephus, Pilate’s contempt for his subjects and his readiness to resort to force that threatened the precarious stability of Judea led him to disperse violently a Samaritan mob that had gathered to hear a prophetic demagogue preach on Mount Gerizim. It was one mistake too far. The outcry from the Samaritans was so great that the legate of Syria, Vitellius, intervened and deposed Pilate in AD 36.

For the next stage of Pilate’s life, one only finds unsubstantiated legends and no objective accounts. The procurator who presided over the most famous trial of history and who has been a byword for moral compromise ever since now passes into obscurity. However, the historical basis for the Gospels’ claims that he existed and their presentation of how he behaved at Christ’s trial can be asserted confidently

~ Peter Harris

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chronologie visuelle des empereurs romains : D'Auguste à Constantin

La dynastie julio-claudienne

Auguste en tant que Pontifex Maximus (détail)

Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Lire la suite...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

EX DEO Release 'Vitellius' Lyric Video - New EP 'Year Of the Four Emperors' is Out Now!

To celebrate the release of their new EP 'Year Of the Four Emperors', Ex Deo have unveiled a stunning lyric video for the EP's penultimate track, 'Vitellius'.

Death metal gladiators EX DEO, the Juno-nominated project of KATAKYLSM frontman Maurizio Iacono, have unleashed their highly anticipated new EP ‘Year Of the Four Emperors’ on Reigning Phoenix Music, via its partnership with Distortion Music Group. The EP is out now digitally and on CD, with a limited edition vinyl to follow on March 14th, 2025. To celebrate, the band has also unveiled a stunning…

0 notes

Text

A black-and-white chalk drawing of the head of a portly man was recently sold at a Christie’s auction as the only work firmly attributed to Marietta Robusti, daughter of the Venetian master Jacopo Robusti, perhaps better known as Tintoretto. Reports from her contemporary biographers suggest that Marietta, who worked in her father’s workshop in the late 16th century, was an accomplished and sought-after artist in her own right. But in the centuries that followed she fell into obscurity. Now, amid a growing movement to reclaim the women artists so often neglected by history, Marietta has the potential to join 16th-century peers such as Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola in the history books – if only researchers could find some more of her work.

‘Marietta had a brilliant mind like her father. She painted such works that men were astonished by her talent,’ writes Carlo Ridolfi, author of a biography of Jacopo Tintoretto and two of his children, Domenico and Marietta, first published in 1642. Nicknamed ‘La Tintoretta’, Marietta – who, according to Ridolfi, dressed as a boy in order to assist her father on his projects – is recorded as having painted many portraits and produced works of her own invenzione. Another of Tintoretto’s early biographers, Raffaello Borghini, reports how Marietta was requested as a court artist by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, and King Philip II of Spain – although ‘Greatly loving his daughter, [Tintoretto] did not want her taken from his sight,’ writes Borghini.

With such glowing accounts of Marietta’s artistic prowess, attempts to rediscover her work have been numerous and in some cases quite inventive. Unfortunately, these endeavours have rarely been successful.

One of the most commonly attributed paintings is a Self-Portrait with Madrigal located in the Uffizi’s Corridoio Vasariano in Florence. The painting shows a young woman in a white dress with her right arm resting on a harpsichord behind her and a music score in the other hand. The Uffizi labels the work as by Marietta Robusti in its online catalogue. However, art historians have questioned the credibility of this attribution based on provenance records, which show that the portrait was attributed to Titian by a Venetian collector in the 17th century.

Most damning of all, though, is the mediocrity of the painting. The art historian Joanna Woods-Marsden comments in her book Renaissance Self-Portraiture (1998) that the rudimentary foreshortening and poor anatomy are hard to reconcile with the praise lauded on Marietta by her biographers. Duncan Bull, writing in the Burlington Magazine in 2009, dismisses it as ‘a feeble work that speaks more of Verona than of Venice, let alone of Tintoretto’s workshop’. The lack of naturalism and the stiffness of the sitter are worlds away from the fluid, energetic style characteristic of a pupil of the Venetian master.

‘Marietta’s special gift,’ according to Ridolfi, ‘was knowing how to paint portraits well.’ This was not unusual praise for 16th-century women artists, who were highly valued as portraitists. Women were considered to have an eye for detail, particularly jewellery and decoration on clothing, which was so crucial in portraiture for demonstrating a sitter’s wealth and status.

Several portraits have been tentatively attributed to Marietta Robusti. These include a Portrait of an Old Man and a Boy in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Rijksmuseum’s Portrait of Ottavio Strada. The attribution of the former painting rested on the signature ‘M R’ on the bottom left of the canvas; after cleaning, it appears that the signature actually reads ‘M 3’. The painting in Amsterdam, currently catalogued as by Jacopo Tintoretto, has received attention because Marietta’s early biographers mention a portrait she painted of the courtier Jacopo Strada. Some art historians argue that the biographers mistakenly cited Jacopo instead of his son Ottavio Strada – and that the Rijksmuseum’s painting is the portrait in question. But this is just one theory.

Plenty of historic catalogue entries attribute other work to Marietta, but evidence of these paintings is now thin on the ground. It is likely that Marietta also helped her father with public commissions, such as paintings in their local church in Venice, the Madonna dell’Orto. But her contributions in this respect are hard to pinpoint.

Just one drawing, therefore, is categorically attributed to Marietta. Head of man, after the antique, which sold at Christie’s in Paris last month for €100,000, depicts the Roman emperor Vitellius drawn from an ancient bust – a copy of which Tintoretto kept in his workshop. Scrawled across the drawing are the words ‘this head is by the hand of madonna Marietta’, probably added by her father to distinguish the drawing from the countless others that would have lain about the workshop.

This drawing is a much-needed example of Marietta’s talents. As Stijn Alsteens, international head of Christie’s Old Master drawings department explains to me via email, ‘Marietta in her time was admired as a portraitist, and the drawing can be said to reflect her interest in physiognomy.’ The drawing, Alsteens says, confirms Ridolfi’s account that Marietta was a gifted member of her father’s studio, on an equal footing with her male counterparts.

In the drawing, Marietta captures the head in soft, swift strokes, economic shading and dashes of highlights. We see the fluidity and movement expected of an artist trained by Tintoretto. On the recto of the sheet is another drawing from Tintoretto’s workshop of unknown attribution portraying the face of Giuliano de’ Medici. ‘Where the recto is mostly a study of light and shadow, the verso focuses on the distinctive features of Vitellius’s face – true to Marietta’s gifts as a portraitist,’ Hélène Rihal, head of Christie’s Old Master drawings department in Paris, said in advance of the sale.

Although the attribution is accepted, it is only one drawing and that poses a dilemma for anyone seeking to restore Marietta’s reputation. The historical evidence has the potential to put Marietta on a par with contemporaries like Fontana or Anguissola. The gaping hole is the physical evidence. For the moment La Tintoretta, the legendary woman artist, remains just that – a legend.

#studyblr#history#art#art history#portrait painting#feminism#italy#veneto#venice#cannaregio#madonna dell'orto#marietta robusti#jacopo robusti#tintoretto#carlo ridolfi#raffaello borghini#maximilian ii holy roman emperor#ferdinand ii archduke of austria#philip ii of spain#ottavio strada#jacopo strada#vitellius

1 note

·

View note

Text

Suetonius in the Life of Vitellius says that according to Cassius Severus and others, the founder of Vitellius' family was a cobbler. I choose to incorporate into my belief system that this was the cobbler from Julius Caesar I.1.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

I love articles with titles like "[bigotry] in the [industry/field that is harmful to its very core]." I'm sure there is, but how do you miss the point that bad

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#what their mums probably called them#ancient rome#roman empire#ancient history#julio claudian dynasty#emperor augustus#emperor tiberius#emperor caligula#emperor claudius#emperor nero#emperor galba#emperor otho#emperor vitellius#emperor vespasian#emperor titus#emperor domitian#emperor nerva#emperor trajan#emperor hadrian#emperor antoninus pius#emperor lucius verus#emperor marcus aurelius#emperor commodus#augustus#tiberius#claudius#caligula#nero#galba#otho

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wip... idk when or if ill finish tbh... how do you even draw puke idk. Evil 3 am drawing lol

Okay blaze from the morning i wanna clarify this isnt like a vent post or nothing i just thought the image of Vitellius making himself puke just to eat more was a level of depravity and disgusting desire that i HAD to draw it

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Triumphal Feast of Vitellius

The emperor Aulus Vitellius (r. 69 CE) had never wanted to be Rome's emperor. Aulus was from a family of court flatterers to the first Caesars, and when his friend Nero (r. 54-68 CE) was dead, and there were no more Caesars to succeed, he was the last man that anyone would have expected to take the throne.

Continue reading...

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

4- Vitellius- you like food, you're chill, I like you.

What does your favourite roman emperor tell about you:

1- Elagabalus: you're into decadent literature and/or queer

2- There is no number two, I only made this about Elagabalus

#to have a recipe for peas named after you is certainly a legacy#rome's biggest gourmand#year of four emperors#roman emperors#roman empire#vitellius

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Banquet triomphal de Vitellius

L'empereur Aulus Vitellius (r. 69 de notre ère) n'avait jamais voulu être empereur de Rome. Aulus appartenait à une famille de flatteurs de la cour des premiers Césars, et lorsque son ami Néron (r. 54-68 de notre ère) mourut et qu'il n'y avait plus de César pour lui succéder, il était le dernier homme que l'on se serait attendu à voir sur le trône.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note

Text

Todays Classicstober is Vitellius, he was a Roman Emperor for 8 months, during the Year of the Four Emperors.

I got carried away colouring this haha

3 notes

·

View notes