#vis a vis: issue 551

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ISSUE 1167: supercockt

09 december 2024

#cocksley and catapult#c&c#webcomic#webtoon#comic#web series#ms paint#artists on tumblr#vis a vis: issue 551

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

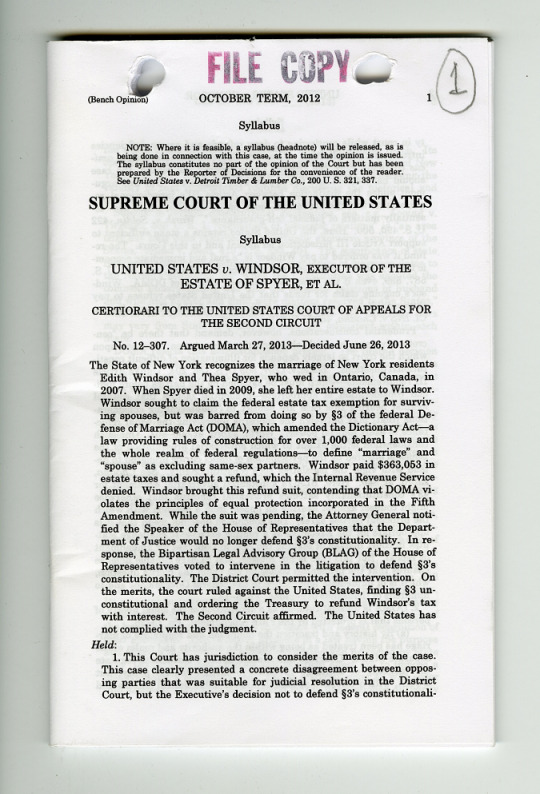

The Supreme Court ruled that the Defense of Marriage Act was unconstitutional on June 26, 2013.

In U.S. v Windsor, SCOTUS held that the federal government could not discriminate against same-sex couples.

Record Group 267: Records of the Supreme Court of the United States Series: Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files

Transcription:

[Stamped: " FILE COPY "]

(Bench Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2012 1 [Handwritten and circled " 1" in upper right-hand corner]

Syllabus

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is

being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued.

The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been

prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader.

See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

UNITED STATES v. WINDSOR, EXECUTOR OF THE

ESTATE OF SPYER, ET AL.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 12-307. Argued March 27, 2013---Decided June 26, 2013

The State of New York recognizes the marriage of New York residents

Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer, who wed in Ontario, Canada, in

2007. When Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor.

Windsor sought to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviv-

ing spouses, but was barred from doing so by §3 of the federal Defense

of Marriage Act (DOMA), which amended the Dictionary Act---a

law providing rules of construction for over 1,000 federal laws and

the whole realm of federal regulations-to define "marriage" and

"spouse" as excluding same-sex partners. Windsor paid $363,053 in

estate taxes and sought a refund, which the Internal Revenue Service

denied. Windsor brought this refund suit, contending that DOMA vi-

olates the principles of equal protection incorporated in the Fifth

Amendment. While the suit was pending, the Attorney General notified

the Speaker of the House of Representatives that the Department

of Justice would no longer defend §3's constitutionality. In re-

sponse, the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (BLAG) of the House of

Representatives voted to intervene in the litigation to defend §3's

constitutionality. The District Court permitted the intervention. On

the merits, the court ruled against the United States, finding §3 un-

constitutional and ordering the Treasury to refund Windsor's tax

with interest. The Second Circuit affirmed. The United States has

not complied with the judgment.

Held:

1. This Court has jurisdiction to consider the merits of the case.

This case clearly presented a concrete disagreement between oppos-

ing parties that was suitable for judicial resolution in the District

Court, but the Executive's decision not to defend §3's constitutionali-

[page 2]

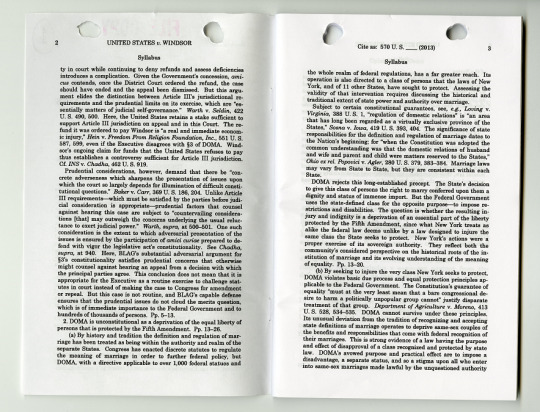

2 UNITED STATES v. WINDSOR

Syllabus

ty in court while continuing to deny refunds and assess deficiencies

introduces a complication. Given the Government's concession, ami-

cus contends, once the District Court ordered the refund, the case

should have ended and the appeal been dismissed. But this argu-

ment elides the distinction between Article Ill's jurisdictional re-

quirements and the prudential limits on its exercise, which are "es-

sentially matters of judicial self-governance." Warth v. Seldin, 422

U. S. 490, 500. Here, the United States retains a stake sufficient to

support Article III jurisdiction on appeal and in this Court. The re-

fund it was ordered to pay Windsor is "a real and immediate econom-

ic injury," Hein v. Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc., 551 U. S.

587, 599, even if the Executive disagrees with §3 of DOMA. Wind-

sor's ongoing claim for funds that the United States refuses to pay

thus establishes a controversy sufficient for Article III jurisdiction.

Cf. INS v. Chadha, 462 U. S. 919.

Prudential considerations, however, demand that there be "con-

crete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of issues upon

which the court so largely depends for illumination of difficult consti-

tutional questions." Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, 204. Unlike Article

III requirements---which must be satisfied by the parties before judi-

cial consideration is appropriate---prudential factors that counsel

against hearing this case are subject to "countervailing considera-

tions [that] may outweigh the concerns underlying the usual reluc-

tance to exert judicial power." Warth, supra, at 500-501. One such

consideration is the extent to which adversarial presentation of the

issues is ensured by the participation of amici curiae prepared to de-

fend with vigor the legislative act's constitutionality. See Chadha,

supra, at 940. Here, BLAG's substantial adversarial argument for

§3's constitutionality satisfies prudential concerns that otherwise

might counsel against hearing an appeal from a decision with which

the principal parties agree. This conclusion does not mean that it is

appropriate for the Executive as a routine exercise to challenge stat-

utes in court instead of making the case to Congress for amendment

or repeal. But this case is not routine, and BLAG's capable defense

ensures that the prudential issues do not cloud the merits question,

which is of immediate importance to the Federal Government and to

hundreds of thousands of persons. Pp. 5-13.

2. DOMA is unconstitutional as a deprivation of the equal liberty of

persons that is protected by the Fifth Amendment. Pp. 13--26.

(a) By history and tradition the definition and regulation of mar-

riage has been treated as being within the authority and realm of the

separate States. Congress has enacted discrete statutes to regulate

the meaning of marriage in order to further federal policy, but

DOMA, with a directive applicable to over 1,000 federal statues and

[NEW PAGE]

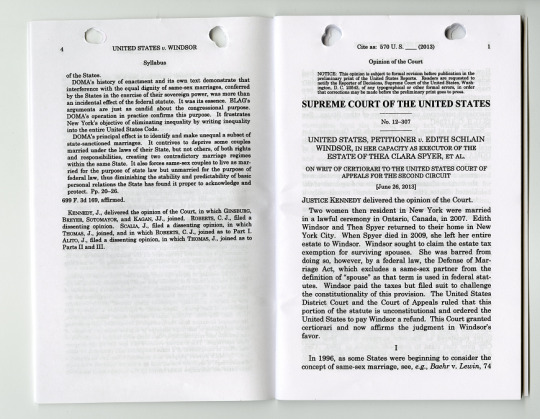

Cite as: 570 U.S._ (2013) 3

Syllabus

the whole realm of federal regulations, has a far greater reach. Its

operation is also directed to a class of persons that the laws of New

York, and of 11 other States, have sought to protect. Assessing the

validity of that intervention requires discussing the historical and

traditional extent of state power and authority over marriage.

Subject to certain constitutional guarantees, see, e.g., Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, "regulation of domestic relations" is "an area

that has long been regarded as a virtually exclusive province of the

States," Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U. S. 393, 404. The significance of state

responsibilities for the definition and regulation of marriage dates to

the Nation's beginning; for "when the Constitution was adopted the

common understanding was that the domestic relations of husband

and wife and parent and child were matters reserved to the States,"

Ohio ex rel. Popovici v. Agler, 280 U. S. 379, 383-384. Marriage laws

may vary from State to State, but they are consistent within each

State.

DOMA rejects this long-established precept. The State's decision

to give this class of persons the right to marry conferred upon them a

dignity and status of immense import. But the Federal Government

uses the state-defined class for the opposite purpose---to impose re-

strictions and disabilities. The question is whether the resulting injury

and indignity is a deprivation of an essential part of the liberty

protected by the Fifth Amendment, since what New York treats as

alike the federal law deems unlike by a law designed to injure the

same class the State seeks to protect. New York's actions were a

proper exercise of its sovereign authority. They reflect both the

community's considered perspective on the historical roots of the in-

stitution of marriage and its evolving understanding of the meaning

of equality. Pp. 13--20.

(b) By seeking to injure the very class New York seeks to protect,

DOMA violates basic due process and equal protection principles ap-

plicable to the Federal Government. The Constitution's guarantee of

equality "must at the very least mean that a bare congressional de-

sire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot" justify disparate

treatment of that group. Department of Agriculture v. Moreno, 413

U. S. 528, 534-535. DOMA cannot survive under these principles.

Its unusual deviation from the tradition of recognizing and accepting

state definitions of marriage operates to deprive same-sex couples of

the benefits and responsibilities that come with federal recognition of

their marriages. This is strong evidence of a law having the purpose

and effect of disapproval of a class recognized and protected by state

law. DOMA's avowed purpose and practical effect are to impose a

disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma upon all who enter

into same-sex marriages made lawful by the unquestioned authority

[page 3]

4 UNITED STATES v. WINDSOR

Syllabus

of the States.

DOMA's history of enactment and its own text demonstrate that

interference with the equal dignity of same-sex marriages, conferred

by the States in the exercise of their sovereign power, was more than

an incidental effect of the federal statute. It was its essence. BLAG's

arguments are just as candid about the congressional purpose.

DOMA's operation in practice confirms this purpose. It frustrates

New York's objective of eliminating inequality by writing inequality

into the entire United States Code.

DOMA's principal effect is to identify and make unequal a subset of

state-sanctioned marriages. It contrives to deprive some couples

married under the laws of their State, but not others, of both rights

and responsibilities, creating two contradictory marriage regimes

within the same State. It also forces same-sex couples to live as mar-

ried for the purpose of state law but unmarried for the purpose of

federal law, thus diminishing the stability and predictability of basic

personal relations the State has found it proper to acknowledge and

protect. Pp. 20-26.

699 F. 3d 169, affirmed.

KENNEDY, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which GINSBURG,

BREYER, SOTOMAYOR, and KAGAN, JJ., joined. ROBERTS, C. J., filed a

dissenting opinion. SCALIA, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

THOMAS, J., joined, and in which ROBERTS, C. J., joined as to Part I.

ALITO, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which THOMAS, J., joined as to

Parts II and III.

[NEW PAGE]

Cite as: 570 U. S. _ (2013) 1

Opinion of the Court

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Washington,

D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order

that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 12-307

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER v. EDITH SCHLAIN

WINDSOR, IN HER CAPACITY AS EXECUTOR OF THE

ESTATE OF THEA CLARA SPYER, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

[June 26, 2013]

JUSTICE KENNEDY delivered the opinion of the Court.

Two women then resident in New York were married

in a lawful ceremony in Ontario, Canada, in 2007. Edith

Windsor and Thea Spyer returned to their home in New

York City. When Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire

estate to Windsor. Windsor sought to claim the estate tax

exemption for surviving spouses. She was barred from

doing so, however, by a federal law, the Defense of Mar-

riage Act, which excludes a same-sex partner from the

definition of "spouse" as that term is used in federal stat-

utes. Windsor paid the taxes but filed suit to challenge

the constitutionality of this provision. The United States

District Court and the Court of Appeals ruled that this

portion of the statute is unconstitutional and ordered the

United States to pay Windsor a refund. This Court granted

certiorari and now affirms the judgment in Windsor's

favor.

I

In 1996, as some States were beginning to consider the

concept of same-sex marriage, see, e.g., Baehr v. Lewin, 74

#archivesgov#June 26#2013#2010s#Pride#LGBTQ+#LGBTQ+ history#U.S. v Windsor#Defense of Marriage Act#same-sex marriage#Supreme Court#SCOTUS

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes

Photo

Once Vigilius was in Constantinople

All this almost made sense. Once Vigilius was in Constantinople under virtual house arrest, Justinian went to work on him. In his first years in Constantinople, Vigilius toed the party line, condemning those who would not condemn the “Three Chapters,” issuing an official Judgment (ludicatum) in 548, then retracting it under extreme pressure from his own retinue and from Latin writers in contact with the recently revitalized orthodox church in Africa. Justinian returned to the offensive in 551 and insisted on having Vigilius’s support, but the pope showed a trace of backbone in taking refuge in the church of Saint Peter (the first pope, after all) at Constantinople and excommunicating those who accepted the new imperial edict. Not long after, Vigilius fled across the water to Chalcedon to the church of Saint Euphemia, symbolic home of orthodoxy since the council there a century earlier.

Then came the point, just as the war in Italy was finally winding down in 553, when Justinian had the confidence to do what no emperor had done in a century: call a council. Meeting in Constantinople under the emperor’s eye in May and June 553, just over a century after Chalcedon, the Second Council of Constantinople did the emperor’s exact bidding. It made no new contribution to theology; it clarified nothing; but it also ceded nothing. In formal words, Chalcedon was reaffirmed, but the “Three Chapters” authors were condemned, and with them the still resistant Vigilius.

Again applied to Vigilius

After the council, pressure was again applied to Vigilius, and in 554 he finally issued another Judgment that did his master’s bidding, condemning the “Three Chapters” and supporting the council. Vigilius was now superfluous and of no interest except as a symbol of the unity of realms. (The acts of the council were even doctored after the fact to make it seem that Vigilius had supported Justinian all along.) Dispatched back to Italy in 555, he died at Syracuse in Sicily en route, the most convincingly humiliated bishop of Rome ever seen. When his successor, Pelagius I, was finally elected in 556, there were too few bishops in the neighboring region to be found to conduct his consecration, and an embarrassing delay ensued kukeri carnival.

Vigilius was lucky that he didn’t make it to Rome, for he would have found that, whatever effect the “Three Chapters” condemnation had on the monophysite opposition, it shocked many westerners. If Justinian was having enough trouble ensuring the stability of his rule in Italy on military terms, the “Three Chapters” edict was decisive in weakening the idea of ecclesiastical authority exercised from Constantinople. No pope after Vi- gilius ever truckled as he had truckled, and for many decades afterward whole segments of the western church remained in continuous rebellion against the idea of condemning the dead and condemning those dead.

Aphthartodocetism

Justinian never relented, and in his last years he devised a new variant on theological subtlety, “aphthartodocetism,” which tried to preserve the serene divinity of Christ by making his sufferings entirely voluntary and even his physical body incorruptible in its godhood. This Jesus only appeared to suffer and die on a cross. Few disciples followed this flag willingly.

No emperor after Justinian would attempt the kind of theological authoritarianism that he practiced, and for good reason. It had failed. No figure of late antiquity believed in the universal unity and consistency of Christianity more than Justinian did, but no figure did more to ensure that it would never be achieved. The monophysite rebellion in the east proved enduring and subsists today in the Jacobite churches. The Nestorians’ withdrawal to the Persian empire proved permanent as well. The disaffection with and suspicion of the western church endured. Vigilius was the weakest of popes, but his failure made all the popes after him stronger. As late as the fifth century, it might have been imagined that Christianity would be genuinely catholic, that is to say, universal. At no point since Justinian has it been possible to imagine such a thing.

0 notes